6. Encourage Useful Failures

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

—Thomas Edison

James Dyson hated the fact that vacuum cleaners often became clogged, lost suction, and left far too much dirt on the floor.1 Described as a “tireless tinkerer,” the British inventor began trying to solve these problems.2 While Dyson tinkered, his wife’s salary as an art teacher kept the family afloat. The couple grew their own vegetables, made their own clothes, and still, they sank deeper and deeper into debt. After many years, Dyson perfected his revolutionary bagless vacuum cleaner. The patented spinning technology separated dirt and dust from the air, eliminating the need for a filter or bag. The transparent design enabled the user to watch the cleaning process in action, something consumers enjoyed immensely.3

Dyson tried to persuade one of the multinational competitors in the market to manufacture the product. These companies resisted, because the product undermined their classic razor-and-blades business model. In other words, the incumbent firms sold vacuum cleaners at a modest margin and reaped huge rewards from an ongoing stream of replacement bag sales. Undeterred by their rejection, Dyson opened his own factory in the United Kingdom. The product became an international hit. Today, James Dyson ranks as one of the richest men in the world; Forbes estimates his net worth at $1.6 billion.4 Queen Elizabeth II knighted him in December 2006. Despite all that success, Dyson loves talking about the importance of failure in his life as an industrial designer. “I made 5,127 prototypes of my vacuum before I got it right,” said Dyson. “There were 5,126 failures, but I learned from each one. That’s how I came up with a solution. So I don’t mind failure.”5 He goes on to argue that we often fool ourselves into believing that successful products emerge from a moment of “effortless brilliance.” To him, failures provide keen insights that enable the invention of unique products. Dyson explains:

“We’re taught to do things the right way. But if you want to discover something that other people haven’t, you need to do things the wrong way. Initiate a failure by doing something that’s very silly, unthinkable, naughty, dangerous. Watching why that fails can take you on a completely different path. It’s exciting, actually.”6

Alberto Alessi stresses the importance of failures too. Known as “the godfather of Italian design,” Alessi joined his family’s housewares company in 1970.7 Over the past four decades, he and his brothers have transformed the firm into an avant-garde design house known for its partnerships with leading architects, designers, and artists such as Phillippe Starck, Michael Graves, and Ettore Sottsass. Alessi has created chic products, such as a lemon squeezer from Starck, a kettle from Graves, and oil and vinegar cruets by Sottsass.8 Revenue has grown at a robust clip in recent years. Alessi readily acknowledges that the firm has made its share of mistakes, though. For instance, the Aldo Rossi Conical Kettle appeared aesthetically pleasing to consumers. Unfortunately, the handle becomes far too hot, rendering it unusable in most households. A phallic-shaped igniter for gas ranges turned out to be a bust too, while not surprisingly provoking a rebuke from Catholic Church leaders in Italy.9 Alessi likes these fiascoes, believe it or not. He says, “I have to remind my brothers how vital it is to have one, possibly two, fiascoes per year. Should Alessi go for two or three years without a fiasco, we will be in danger of losing our leadership in design.”10

At the company’s headquarters, weekly design meetings take place in an interesting setting—the company’s private museum, which prominently features Alessi’s major flops. The company leaders want to remind the designers that no one has a perfect batting average, regardless of their creativity or effort. They want the designers not to be afraid to take risks, or to fear being punished for failures. Carlo Ricchetti, Alessi’s head of production, explains, “We use the archive museum for designers who want to work with us to encourage them to experiment with new ideas and appreciate the value of good ideas.”11 Alessi expounds on this notion: “I like fiascoes, because they are the only moment when there is a flash of light that can help you see where the border between success and failure is.”12

Many chief executives express a fervent desire to encourage risk-taking and innovation in their organizations. They proclaim that it’s “OK to fail” at their firms. However, few leaders back up all that talk with action. The words from the top seem to ring hollow to many employees, who fear acknowledging their mistakes and failures. They believe that a misstep could cost them their job or, at a minimum, derail the upward trajectory of their careers. They recall far too many instances when their colleagues seemed to be punished for taking a risk and experiencing a failure.

Why Tolerate Failure?

Problem-finding requires a very different mindset with regard to failure. How does creating a culture that genuinely tolerates a healthy dose of risk-taking and failure help to surface the problems and threats facing a firm? First, if people fear punishment, they will be far less likely to admit mistakes and errors. Without an understanding of where and how these mistakes are occurring, senior leaders cannot spot patterns and trends. They cannot connect the dots among multiple incidents to identify major problems of and threats to the organization.

At Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis, Chief Operating Officer Julie Morath instituted a “blameless reporting system” for medical accidents.13 She empowered people to communicate confidentially and anonymously about medical accidents without being punished. Naturally, some errors, such as those involving negligence or malfeasance, were deemed “blameworthy acts.” Most incidents, however, did not involve personal carelessness; they indicated more systemic problems at the hospital. Morath’s initiative aimed to surface as many of the hospital’s problems as possible so that she could identify the underlying causes of these accidents. She wanted to shine a light on errors to expose the vulnerabilities in the hospital’s systems and processes. One physician commented about the aftermath of a procedure that did not go as planned: “It wasn’t the old ABC model of medicine: Accuse, Blame, Criticize. What kicked in was a different model: blameless reporting. We sat down and filled out a safety report and acknowledged all the different components that went wrong and did root cause analyses.”14 The doctors and nurses implemented important system improvements as a result of those analyses. In fact, the number of medical errors reported by staff members actually rose after Morath instituted her blameless reporting system. The rise did not indicate more harm being done to patients, but rather more comfort with disclosing errors and accidents. The heightened transparency actually led to substantial safety improvements at Children’s over time.

Heightened tolerance of failure not only surfaces errors that have already occurred; it encourages experimentation to increase the pace of problem-finding. As the employees at leading industrial design firm IDEO say, “Fail early and often to succeed sooner.”15 When people engage in low-cost, rapid experiments, they do not immediately discover the perfect course of action for the future. Instead, they gradually identify all the ideas that will not work, all the problems that can derail a particular strategy or initiative. As my colleague Amy Edmondson says, “It’s the principle of the scientific method that you can only disconfirm, never confirm, a hypothesis.”16 Over time, many failed experiments enable us to discover what will work. Too often, though, companies only seem to encourage pilots and trials that aim to confirm what executives already believe, rather than to determine what will not work.

The Wharton School’s Paul Schoemaker and his coauthor Robert Gunther argue that firms should design some low-cost experiments in which the probability and expectation of failure is relatively high. They describe these types of experiments as “deliberate mistakes.” In these instances, managers seek to validate (or disconfirm) key assumptions before moving forward with a broader initiative. They deliberately set out to prove what could go wrong.17

Capital One, the credit card company, does not rely strictly on publicly available credit scores to evaluate potential customers; after all, each of its rivals has that same information. Instead, it conducts thousands of controlled experiments each year. Each experiment sets out to test a particular hypothesis about the factors that affect individual risk profiles. Undoubtedly, some of its mailings induce “bad risks” to sign up for a credit card. Capital One will lose money on those customers, and on some tests overall. In that sense, those experiments might be described as failures. However, each of these tests helps the company refine its proprietary algorithms that aim to predict the creditworthiness of each consumer. CEO and cofounder Richard Fairbank argues that the long-run profitability of the business rises as these algorithms become more accurate. Indeed, for many years, these algorithms provided Capital One with an ability to attract “good risks” and avoid “bad risks” more effectively than many rivals. Today, many of its rivals have emulated the firm’s strategy of experimentation.18

Intolerance of failure diminishes problem-finding capabilities in one other important way. If we reassign or dismiss individuals soon after every failure, we lose valuable learning opportunities. The people responsible for a mistake often know the most about what went wrong and how to fix it moving forward. If we ostracize or dismiss these people, we lose their voices in the learning process. Perhaps the blame game drives out learning.

In some organizations, people want to forget failure as soon as possible; they do not reflect on those situations because it’s painful and uncomfortable to do so. They prefer to learn from their past successes. However, we often attribute our successes to the wrong factors. We reduce a situation of complex causality to a simple story of how a particular decision led to an effective outcome. Scholars Philippe Baumard and William Starbuck have argued that “As it is often unclear whether a sequence of events adds up to success or failure, organization members slant interpretations to their own benefit.”19 We certainly discount the role of luck in many instances; we prefer to attribute good outcomes to our intelligence and thoughtful planning. Baumard and Starbuck conclude that “Research about learning from success says many firms improve their performance, but firms can over-learn the behaviors that they believe foster success and they become unrealistically confident that success will ensue.”20

Learning from failures has its own shortcomings, though. People responsible for failures often try to present themselves in a positive light during many postmortems, and thereby distort what actually happened. A phenomenon known as “the fundamental attribution error” inhibits effective learning. By that, psychologists mean that we often attribute others’ failures to their personal shortcomings, while explaining away our own errors as an outcome of unforeseeable external factors.21 To identify the true problems in our organizations, we need to make people comfortable with admitting their own mistakes while avoiding pointing their finger at others. We have to lead by example, acknowledging our own missteps as leaders. When we talk about giving people “the freedom to fail,” we have to be willing to back up our words with actions. Figuratively speaking, we must be willing to hold weekly meetings in a museum that features our past fiascoes, as well as our successes.

Does this mean that leaders should tolerate all failures? Of course not! Failures come in many shapes and sizes. Some failures may be tolerated; others should not be. Most executives do not have a clear set of criteria for differentiating the unacceptable failures from the ones that may be useful learning opportunities. The lack of clarity leaves employees unsure how they will be treated if they try something new and fail. The uncertainty regarding what constitutes a “blameworthy act” serves to suppress risk-taking, even when senior leaders have strongly expressed their desire not to punish people who fail.22

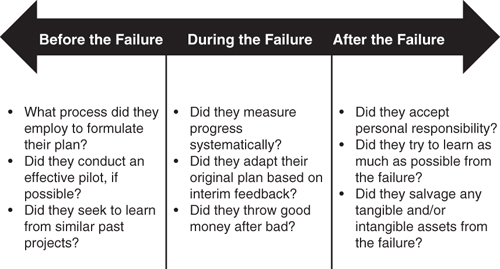

How, then, does one distinguish failures that are more acceptable from those that are far more inexcusable? Leaders need to examine how individuals behaved before, during, and after the failure (as shown in Figure 6.1). They have to understand the decision-making process that led to a particular course of action. They must examine how people reacted and adapted as the plan veered off course. Finally, leaders need to evaluate how individuals behaved in the aftermath of the failure, particularly the extent to which they accepted responsibility for their mistakes and tried to learn from them. Perhaps most importantly, leaders need to communicate to the entire organization their criteria for distinguishing between tolerable and inexcusable failures.23

Before the Failure

When evaluating a failure, leaders need to examine the decision-making process employed by the key players. My research, as well as the studies conducted by other scholars, has identified certain attributes of high-quality decision-making processes. These characteristics do not guarantee that a good outcome will result, but they raise the probability substantially. In an effective decision-making process, groups generate and evaluate multiple alternatives. They surface and test key assumptions. Groups gather information that disconfirms existing views, not simply data that support the conventional wisdom. They gather information from a wide variety of sources, striving to find unbiased experts who can provide a fresh perspective. Effective teams engage in a vigorous debate while keeping the conflict constructive. Leaders encourage the expression of dissenting views. They genuinely want to hear what others think, rather than simply engaging in what management scholar Michael Watkins calls a “charade of consultation.”24 Effective teams consider worst-case scenarios and develop contingency plans. Ultimately, leaders should build commitment and shared understanding before moving forward with implementation. When examining a failure, you need to ask yourself: Did the key players employ a decision-making process with these attributes? Or did they fail to consider multiple options, quash dissenting views, and gather information in a biased way? If so, you should be much more cautious about excusing the failure.25

What else should we consider when evaluating a failure? We need to understand how goals were established at the outset of the project. Did the leader of the initiative establish a clear set of objectives and communicate those effectively to everyone involved in the implementation effort? When multiple goals exist, project leaders must make their priorities clear so that others know how to make trade-offs if necessary as the effort unfolds. Moreover, one should look for evidence of clear metrics and milestones that were established to track progress against the goals over time.

We should examine too whether a project’s leaders conducted appropriate prototyping and/or pilot studies before implementing their course of action. Did they conduct a test of modest cost and risk before diving headfirst into a massive rollout of the project? Did they design a good pilot, or did they stack the deck to get the result that they desired? During my research, one retailer explained why a recent pilot of a new concept had proven problematic when conducted in a handful of the chain’s stores. Senior managers at the corporate office “held the stores’ hands” during the pilot, working alongside the store management team and the associates each day. The corporate officers wanted to make the pilot as successful as possible. Given that interventionist behavior, the pilot proved to be a very poor test of whether this concept could be rolled out effectively throughout the chain. Thus, one should always ask not only if a pilot was conducted, but how it was performed.

Finally, we ought to consider whether a project’s leaders tried to learn from past successes and failures before embarking on their chosen course of action. Did they repeat past missteps? If so, did those mistakes occur because the project’s leaders failed to examine the best and worst practices of the past? Did they fail to learn from history?

During the Failure

Failures certainly should be deemed inexcusable if a project’s leaders violate the organization’s values and principles or, worse yet, break the law during the implementation process. Beyond identifying such egregious behaviors, we should examine whether a project’s leaders measured progress systematically. Did they gather feedback from multiple voices and assess progress against the original goals and objectives on a regular basis? As negative feedback emerged, or external conditions changed, did the project’s leaders adapt their original plan? We would like to see evidence of real-time learning and adjustments.

At some point, though, a project’s leaders should at least consider cutting their losses. In assessing a failure, one must ask: Did individuals “throw good money after bad” in this situation? Too often individuals allow the size of past investments to affect their decision regarding whether to move forward with a course of action, even if those investments are irrecoverable. Prior investments represent sunk costs, which should be irrelevant to current choices regarding whether to move forward with a project. However, research shows that individuals tend to pursue activities in which they have made substantial prior investments. Often, they become overly committed to certain activities despite consistently poor results. As a result, individuals make additional investments in the hopes of achieving a successful turnaround. They escalate their commitment to a deteriorating situation.

Several experimental studies have demonstrated that people fail to ignore sunk costs when making investment decisions. For instance, Barry Staw’s 1976 study represents one of the first laboratory experiments aimed at testing the sunk-cost effect.26 Staw assigned business students the role of a senior corporate manager in charge of allocating resources to various business units. One half of the subjects made an initial resource allocation and received feedback on their decision. Then the subjects made a second resource allocation to the business units. The other half of the subjects did not make the initial allocation. Instead, they received information about the previous allocation, along with feedback.

Staw found that the subjects who made the initial investment decision themselves chose to allocate a higher dollar amount in the second period than those who did not make the initial allocation. In addition, Staw gave one half of the students positive feedback regarding the initial allocation, while the other half received negative feedback. Subjects allocated more dollars to the poorly performing business units than to successful ones. This supported the prediction that individuals would commit additional resources to unsuccessful activities in order to justify past actions.

Do real managers make similar mistakes, just as these students did in the laboratory? Staw and his colleague, Ha Hoang, decided to find out. They collected information on National Basketball Association (NBA) draft picks over a seven-year period.27 Staw and Hoang argued that draft order should not predict playing time in the NBA, after controlling for productivity, unless management has allowed sunk costs to shape their decisions. In other words, a number-one draft pick should not garner more playing time than the twenty-fifth pick in the draft if both players have performed equally well in the NBA up to that point in time. The study’s results indicate that sunk costs do matter. The players’ draft order affects playing time, length of service in the league, and the probability of being traded by their initial team. These effects hold even when controlling for actual performance in the league. In other words, when making decisions, management and coaches tend to overweigh the fact that they have expended a great deal of resources for a particular player. They continue investing in that player for years in hopes of justifying their past expenditures. They throw good playing time after bad.28

One might argue that a study of basketball players does not prove that business executives have a hard time cutting their losses. In fact, research shows that people in all fields, including business, have a hard time ignoring sunk costs. As a classic example, consider the construction of the Concorde, the commercial supersonic jet built in the 1970s. As you may recall, the Concorde flew between Europe and the United States for twenty-seven years, making the trip at record speeds—half the time it took a commercial airliner to travel from Paris to New York. In the relatively early stages of that project, it became quite clear that it had virtually no chance of being a financial success. British and French business and political leaders nearly canceled the project. However, they chose to plow ahead, arguing that they did not want to “waste” the vast amount of resources that already had been expended. Ultimately, the cost of developing the Concorde exceeded the original budget by 500%. The investment never yielded a positive financial return.29

Given overwhelming evidence that human beings are susceptible to the sunk-cost effect, we must look out for this phenomenon when examining failures. We have to examine the evidence to determine whether managers expressed concern about wasting prior investments, and thus poured additional funds into a failing project. Yes, persistence can be valuable. Sometimes, we want our managers to push through obstacles; no one likes a quitter, as they say. However, we must be concerned if someone ignores all advice and evidence to the contrary and continues to throw good money after bad. We certainly should be wary if an individual or team appears to have a track record indicating a reticence to cut their losses when projects go south.

After the Failure

What about a manager’s behavior after a failure? How should one assess that conduct to determine whether a failure should be deemed tolerable versus inexcusable? To begin, a project leader needs to take responsibility for his or her mistakes. This person cannot point fingers at others and dodge accountability. Former Secretary of State Robert McNamara shared an interesting story with me about President John F. Kennedy in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Kennedy told his advisers that he would address the nation on television, at which time he would say, “The buck stops here. I was responsible. It was a miserable failure. Success has many fathers. Failure has none. But, in this case, I am the father, and it was my failure.” McNamara recalls that he offered to appear on television shortly after Kennedy’s speech. He would explain that the entire Cabinet bore responsibility, because none of its members had objected to the invasion plans. They had given the president poor advice and counsel. McNamara recalls being rebuffed by Kennedy. The president replied, “No, no, Bob. It was my responsibility. I didn’t have to take the advice. I have to stand up and take responsibility.”30 We would like to see similar behavior on the part of managers in our organizations who have been responsible for failures. We do not want them to deflect blame to their team; we want them to acknowledge that they made the ultimate decisions.

In the aftermath of failures, we also should expect to see managers conducting a systematic “after-action review.”31 They should be willing to bring in outside, unbiased facilitators to help lead that postmortem analysis. The managers should not only derive learning from the incident for themselves; they should actively try to share that learning with others throughout the organization. They need to be willing to help others avoid making the same mistakes again.

Last, we should examine whether managers tried to salvage certain assets, both tangible and intangible, in the wake of the failure. Did they harvest the project for valuable resources that might be exploited elsewhere in the organization? Pharmaceutical companies now systematically examine past research projects that ended in failure, hoping to find other uses for the drug. For instance, at Eli Lilly, the company’s leadership team “assigns someone—often a team of doctors and scientists—to retrospectively analyze every compound that has failed at any point in human clinical trials.”32 According to the Wall Street Journal, many Eli Lilly products have emerged from an analysis of prior failed research efforts. Consider Evista, a popular drug for osteoporosis, which now generates more than $1 billion in revenue per year for the company. That drug emerged from a failed research project aimed at developing a new contraceptive.33 Managers at all companies should mine their failures in hopes of salvaging intellectual property, as well as physical assets, which may be valuable in other uses moving forward.

To close the chapter, let us consider the attitude toward failure at one of the world’s most creative companies—Pixar Animation Studios. Many people marvel at the success of Pixar, creators of blockbuster movies such as Toy Story and Finding Nemo. The company’s origins trace back to 1984, when John Lasseter left Disney to join filmmaker George Lucas’s computer graphics group. Two years later, Steve Jobs acquired this unit from Lucas for $10 million, and it became known as Pixar. For years, the company produced award-winning short films (known as shorts) as well as commercials. Then, in 1995, Pixar released its first feature film; Toy Story became the highest-grossing film in the nation and received several Academy Award nominations. A string of critically acclaimed and financially successful feature films followed. Meanwhile, Disney’s vaunted animation studios languished. Disney acquired its principal rival, Pixar, for $7.4 billion in 2006. After the deal closed, the Pixar team took the lead in trying to reinvigorate the Disney studios.34

Randy Nelson serves as the dean of Pixar University—the company’s educational and developmental program for its employees. Nelson helps employees learn how to become better animators. He wants them to view “art as a team sport”—that is, he hopes they will see that the best, most creative films are products of collaboration, not simply individual genius.35 To do so, he brings employees into classes where they “make art together and flop publicly.”36 During a session, Nelson puts each illustration on the wall. Then he critiques each person’s work in front of his or her peers. He believes that constructive feedback is essential to producing great work; people must learn to take risks, listen to critiques, and improve their work. “You need an environment to foster risk-taking and error recovery,” says Nelson. “You have to honor failure because failure is just the negative space around success.”37

Pixar believes strongly in honoring failure, as well reminding everyone that even the most creative and successful animators get it wrong at times. As you walk through the halls at Pixar, you see many sketches that were cut from various films.38 These creative failures remind everyone that truly creative and innovative risk-takers will fail on more than one occasion. The walls serve a purpose similar to the fiascoes displayed in Alessi’s museum.

Pixar also understands the value of rapid, relatively low-cost experimentation. It knows that reducing the time and expense associated with a mistake makes failure that much more palatable. For this reason, Lasseter has restarted the production of animated shorts at Walt Disney Studios—a practice that had occurred only sparingly in recent years. Throughout Pixar’s history, Lasseter and others have used shorts as a mechanism to experiment with and refine various computer animation techniques. Interestingly, Walt Disney built his studio in the 1930s based on a series of popular shorts, earning ten Academy Awards for them between 1932 and 1942.

Don Hahn, producer of The Lion King, points out that “Shorts have always been a wellspring of techniques, ideas, and young talent.”39 Now, it seems that Lasseter is returning Disney animation to its roots in hopes of rekindling the creativity that, once upon a time, made the Disney animators the envy of the entertainment world.

Lasseter has asked young talent at the studio to direct these five-minute shorts. The budget for a short represents less than 2% of the money required to fund a major animated film. It costs $2 million or less to produce a five-minute short, while the expense for a feature film often runs well over $100 million.40 Chuck Williams, a veteran story artist at the company, commented on the program:

“They allow you to develop new talent. Shorts are your farm team, where the new directors and art directors are going to come from. Instead of taking a chance on an $80 million feature with a first-time director, art director or head of story, you can spend a fraction of that on a short and see what they can do.41

Already, Lasseter’s program has identified someone with the potential to direct a feature film. After watching a quirky five-minute short titled Glago’s Guest, Lasseter chose its director, Chris Williams, to take over as the director on Bolt—a Disney computer-animated film released in November 2008. Williams had never directed a feature film, but Lasseter used the five-minute short as training ground for him.42

With this program, Lasseter has deployed a relatively small amount of capital, yet provided talented up-and-comers an opportunity to try their hand at directing their first animated film. The cost of a failure is quite low. He can encourage young talent to take risks without worrying about a huge financial loss in the case of a failure. The time required to conduct these experiments also is quite low—shorts do not take years to produce. Some shorts will not work out. Through the development process, however, Lasseter and his team will identify the techniques and practices that do not work as effectively as they should at the Disney studio. They will find the problems that have hindered Disney’s success over the past decade. Moreover, they will identify people who may not be strong enough to direct feature-length films.

Other firms should take notice. They should look for their own low-risk, low-cost opportunities to spark innovation and creativity, while simultaneously developing and evaluating young, talented employees. After all, when failures are costly, no leader wants to tolerate them. The most useful failures enable us to learn quickly and inexpensively.

1 For extensive details on James Dyson and the history of the firm that bears his name, see the company’s website: http://www.dyson.com/about/story/.

2 Vorasarun, C. “Clean machine.” Forbes. March 24, 2008.

3 Clark, H. “James Dyson cleans up.” Forbes. August 1, 2006.

4 Ibid.

5 Salter, C. “Failure doesn’t suck.” Fast Company. May 2007.

6 Ibid.

7 Wylie, I. “Failure is glorious.” Fast Company. September 2001.

8 Kamenev, M. “Alessi: Fun design for everyone.” Business Week. July 25, 2006.

9 http://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/ebuzz/0508/fellows.html.

10 Wylie, I. (2001).

11 http://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/ebuzz/0508/fellows.html.

12 Wylie, I. (2001).

13 I have published a case study about Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minneapolis, along with my coauthors Amy Edmondson and Anita Tucker, based on a series of interviews with leaders at that hospital. Edmondson, A., M. Roberto, and A. Tucker. (2002). “Children’s Hospital and Clinics (A).” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-302-050. This section also benefits from my time spent with Julie Morath and Dr. Chris Robison when they visited my class during the first occasion on which I taught the case study to MBA students. A supplemental case also has been written, helping inform students how the patient safety initiative evolved from 2002 to 2007. See Edmondson, A., K. Roloff, and I. Nembhard. (2007). “Children’s Hospital and Clinics (B).” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-608-073. For more information about Children’s patient safety efforts, see also Shapiro, J. “Taking the mistakes out of medicine.” U.S. News and World Report. July 17, 2000.

14 Edmondson, A., M. Roberto, and A. Tucker. (2002).

15 Kelley, T. (2001). The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm. New York: Doubleday. p. 232.

16 McGregor, J. “How failure breeds success.” Business Week. July 10, 2006.

17 Schoemaker, P. and R. Gunther. (2006). “The wisdom of deliberate mistakes.” Harvard Business Review. June: 108–115.

18 This section draws from a case study about Capital One that is taught in many strategy courses. See Anand, B., M. Rukstad, and C. Paige. (2000). “Capital One Financial Corp.” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-700-124. In addition, this section benefits from what I learned when Capital One CEO Richard Fairbank visited my class in 2001.

19 Baumard, P. and W. Starbuck. (2005). “Learning from failures: Why it may not happen.” Long Range Planning. 38: 281–298. This quote appears on pages 283–284.

20 Baumard, P. and W. Starbuck. (2005). p. 282.

21 Ross, L. (1977). “The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process.” In L. Berkowitz (ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (vol. 10, pp. 173–220). New York: Academic Press.

22 For more on tolerating failure, as well as the types of questions that leaders should consider when evaluating failures, see Farson, R. and R. Keyes. (2002). “The failure-tolerant leader.” Harvard Business Review. August: 64–71.

23 Sim Sitkin defines intelligent failures as those that provide bountiful opportunities for learning and improvement. In that sense, they are perhaps not only excusable, but, to some extent, desirable for the organization. Sitkin identifies several attributes of intelligent failures: carefully planned action, uncertain outcomes, modest scale and scope, executed efficiently, and familiar territory where learning can easily take place. See Sitkin, S. B. (1996). “Learning through failure: The strategy of small losses.” In M. D. Cohen and L. S. Sproull (eds.). Organizational Learning (pp. 541–578). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

24 Personal conversations with Michael Watkins, professor at the Institute for Management Development (IMD) in Lausanne, Switzerland.

25 For an examination of my research on decision-making processes, see Roberto, M. (2005). Why Great Leaders Don’t Take Yes for an Answer: Managing for Conflict and Consensus. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. That book contains many citations to academic articles I have written regarding the attributes of high-quality decision processes. In addition, one should examine the work of scholars such as Kathleen Eisenhardt and Irving Janis. For instance, see Janis, I. (1989). Crucial Decisions. New York: Free Press; Bourgeois, L. J. and K. Eisenhardt. (1988). “Strategic decision processes in high velocity environments: Four cases in the microcomputer industry.” Management Science. 34: 816–835; Dean, J. and M. Sharfman. (1996). “Does decision process matter?” Academy of Management Journal. 39: 368–396. For a review of studies in this area, see Rajagopalan, N., A. Rasheed, and D. Datta. (1993). “Strategic decision processes: Critical review and future directions.” Journal of Management. 19: 349–364.

26 Staw, B. M. (1976). “Knee deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 16: 27–44.

27 Staw, B. M. and H. Hoang. (1995). “Sunk costs in the NBA: Why draft order affects playing time and survival in professional basketball.” Administrative Science Quarterly. 40: 474–494.

28 For additional studies on the sunk-cost effect, see the following: Arkes, H. R and C. Blumer. (1985). “The psychology of sunk cost.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 35: 124–140; Brockner, J. (1992). “The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: Toward theoretical progress.” Academy of Management Review. 17(1): 39–61.

29 http://www.concordesst.com/history/eh5.html#n.

30 Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara told this story to me and my students when he visited my class in the spring of 2005.

31 David Garvin has written extensively on the topic of after-action reviews, as conducted by the U.S. Army. See Garvin, D. (2000). Learning in Action: A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

32 Burton, T. “Flop factor: by learning from failures.” Wall Street Journal. April 21, 2004. p. A1.

33 Ibid.

34 For a complete history of Pixar Animation Studios, see Price, D. (2008). The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Knopf.

35 Bunn, A. “Welcome to Planet Pixar.” Wired. December 2006.

36 Sanders, A. “Brainstorm Zone.” San Francisco Business Times. May 6, 2005.

37 Bunn, A. (2006).

38 Sanders, A. (2005).

39 Solomon, C. “For Disney, something old (and short) is new again.” New York Times. December 3, 2006.

40 Grover, R. “Disney bets long on film shorts.” Business Week. May 4, 2007.

41 Solomon, C. (2006).

42 Grover, R. (2007).