7. Sales Compensation Accounting

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Review various accounting and finance issues that affect the design of sales compensation and sales/commission programs

• Describe general accounting practices as they relate to sales compensation programs

• Explore the design implications, using a hypothetical base and sales commission program

• Examine the various components of a sales compensation program

• Review the accounting control and audit triggers for a sales compensation program

• Identify the various sales compensation allowances paid to a typical salesperson

• Review IRS rules and regulations that relate to sales compensation allowances

• Examine commission accounting processes using commission accounting software

Sales compensation is another important component of a total compensation system. There are many financial and accounting dimensions to the design, implementation, and administration of sales compensation plans. The design dimension that has significant financial and accounting implication is the concept of sales commissions. Commission accounting is also an important consideration. This chapter analyzes all these accounting and finance dimensions as they affect commission program design, implementation, and administration.

General Accounting Practices

Sales compensation plans are specifically designed to compensate sales personnel. Sales compensation is paid to sales professionals to generate revenue for the company. Sales compensation, especially sales commission plans, is therefore directly tied to the fluctuations in sales revenue. That is, as more revenues are generated, the more sales commission is earned by sales professionals, (and vice versa). So, the variable portion of sales compensation directly correlates with sales revenue. So variable sales compensation can be considered a direct cost (that is, one directly traced to a specific cost object). It can be considered a part of absorption costing.

In cost accounting, the cost designations are as follows:

• Direct costs

• Indirect costs

• Fixed manufacturing overhead

• Variable manufacturing overhead

• Selling, general, and administrative expenses

In managerial accounting, when specific product costs need to be calculated, different methods are available for use: absorption costing (job-order costing and process costing) and variable costing. In absorption costing, all manufacturing costs are absorbed into the product cost, whether they are variable or fixed. Not so in variable costing, where only manufacturing costs that vary with output are absorbed into the product cost.

Within this context, the variable costs for sales compensation (that varies with the number of units sold) can be considered a direct product cost. But under current Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) accounting, the variable portion of sales compensation is considered a selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expense, which is recognized in the current period. Note all managerial accounting-based costing systems (job-order, process, variable) categorize the variable portion of sales compensation as an SG&A expense. This is in contrast to a factory manager’s salary, which currently is a fixed manufacturing overhead expense. In absorption costing, the factory manager’s salary is classified and absorbed into the product’s cost. This is not the case under variable costing. In variable costing, the factory manager’s salary would be included in the SG&A expense. This is the case even though both the factory manager’s salary and the salesperson’s variable compensation have a somewhat similar contribution to the product’s cost. This issue remains unresolved.

The sales commission expense is reported when the company has incurred the expense and a liability. This is also when the sales commission is earned by the salesperson. Commission expense is reported as a selling expense along with other selling and administrative expenses.

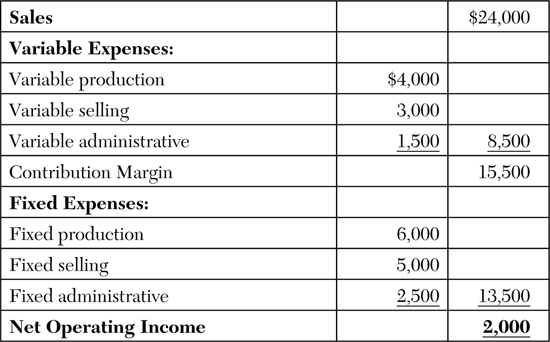

Another sales compensation accounting issue should be noted here. Some organizations believe that separating fixed and variable costs can better assist in forecasting and controlling costs. Therefore, some organizations use the contribution format income statement. In the contribution approach, the objective is to determine the contribution margin (the amount remaining from sales revenues after variable expenses are deducted). The contribution margin determines the amount contributed toward covering fixed expenses and then profit.

In the contribution margin approach, sales compensation is divided into a variable portion, which goes toward calculating the contribution margin, and a fixed portion, which is deducted after the contribution margin is calculated. Exhibit 7-1 shows an example.

Exhibit 7-1. Contribution Approach

Organizations that use activity-based costing as an internal decision-making tool define five levels of activity:

• Unit

• Batch

• Product

• Customer

• Organization sustaining

Sales compensation costs in an ABC system will normally fit under two activity pools: customer orders and customer relations. These costs are regarded as selling expenses. The activity measures used are usually the number of customer orders (for customer orders) and the number of active customers (for customer relations).

Having described the current general accounting practice for variable sales compensation or sales commission plans, we now look at specific accounting and finance issues that determine the structure of a typical sales compensation plan. Then we go on to the issues specific to commission accounting.

Sales Compensation Plans

Sales compensation plans can be structured as follows:

• A base, commission, and bonus plan

• A base and bonus plan

• A base-only plan

• A commission-only plan

The structure that a company adopts is based on the sales strategy of the company and the desired salesperson behavior. Other triggers are intended to direct salesperson actions toward achieving specific sales goals and targets. Our main concern here is to analyze the accounting and finance issues that are a part of the sales compensation plan design and administration. In this context, we look at a base, commission, and bonus plan, which by its very nature has more accounting and finance issues than the other sales compensation structures.

Before analyzing the base, commission, and bonus sales compensation plan, let’s first define the sales commission payment. BusinessDictionary.com defines the sales commission payment as follows:

The amount of money that an individual receives based on the level of sales he or she has obtained. The sales person is provided a certain amount of money in addition to his/her standard salary based on the amount of sales obtained.1

1 www.businessdictionary.com.definition/sales-commission.html#ixzz1oDlkCaOh.

The main element of any sales compensation plan is the use of variable pay. The objective is to align the sales and marketing objectives of the organization with the specific objectives of the salesperson. The sales targets or quota targets that can be used in establishing the “right” sales compensation incentives include the following:

• Sales volume: The number of sales volume over a specified time period.

• New business: Sales to new customers. This may require a great deal of cold-calling, prospecting, converting, and closing.

• Retaining sales: Keeping customers from one sales time period to another.

• Product mix: The organization might want to sell a predetermined mix of products. This will help the competitiveness of the company by selling the whole product line, upselling and cross-selling up and down the product line.

• Win-back sales: This is a sale made to old customers who are being regained as customers.

• New product sales to existing customers: This is sales of new products to existing customers.

• Selling across the company’s product lines: Cross-selling and upselling.

A Cautionary Note on Using Sales as a Commission Trigger

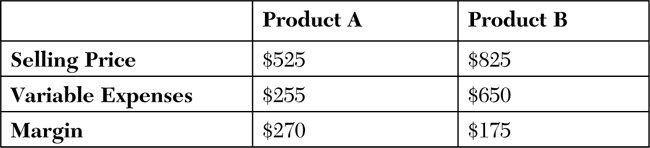

When deciding on targets or measures to trigger sales commission payouts, consider this: If sales volume is used as the exclusive triggering measure, this could lead to a reduction in profit. Let’s demonstrate this with an example (see Exhibit 7-2). Suppose, for instance, that a company has two products in its portfolio, Product A and Product B.

Exhibit 7-2. Analyzing The Effects of Sales as a Commission Trigger

If the sales personnel were paid a 15% commission on sales, they would clearly focus their efforts on selling Product B, although Product A has a greater contribution margin. Focusing on Product B will give the salesperson a higher commission payout. As far as the company is concerned, however, selling more of Product A will give the company a higher profit from which they could cover their fixed expenses and generate a higher net income.

So, if the company sets commissions on the contribution margin or a combination of factors, the likelihood is greater that the salespeople will be encouraged to sell a mix of Products A and B. If fixed costs are not affected by the sales mix, the company can achieve a higher level of profitability if the salesperson is encouraged to sell a mix of products and not just the product with the highest commission potential.

The base, commission, and bonus structure is by far the most common sales compensation structure used by organizations that engage salespeople to generate revenue. Several advantages are associated with compensation plans that combine base salaries with commissions, including the following:

• The plans motivate the sales force to produce greater effort and results.

• The plans enable companies to provide additional rewards to superior salespeople.

• The structure of these plans facilitates the close correlation of compensation with sales performance.

• The plans are generally fairly easy to administer.

Note that in addition to commissions, compensation paid to sales personnel may include expense accounts, automobile leases, advances against future commission earnings (called draws), and sales contests.

Expense accounts are common in many industries. Salespeople routinely use business lunches, dinners, and other networking occasions to close deals. Salespeople often use their own vehicles to travel long distances to meet with customers, and so they expect the company to cover their vehicle expenses (as a business requirement). Providing these compensation elements in the sales compensation package is a competitive requirement if the company intends to hire and retain the highest-caliber sales professionals. You will learn more about these elements of a sales compensation plan later in this chapter.

Sales contests are another compensation element organizations use to motivate sales personnel. Under these programs, sales personnel who beat their annual sales targets or quotas are rewarded with a company-paid trip to an exotic location (or any other reward that has a prestige factor attractive to high-achieving sales personnel). Sales contests can be highly motivational.

Because of these reasons, the company might establish quota clubs. Quota club memberships are reserved for sales personnel who on a year-to-year basis continue to beat their target achievement numbers. As indicated, the annual quota club event often takes place in an exotic location. During these quotas club events, organizations celebrate the top performers, who are thus motivated and encouraged to outdo their current-year performance during the next sales cycle.

Now let’s analyze in detail a hypothetical sales compensation plan with a base, commission, and bonus structure from a finance and accounting perspective. Using this plan, we will discuss both the relevant potential and actual accounting and finance issues.

Accounting Issues Impacting Sales Compensation Program Design

A number of specific accounting and finance issues impact the design of sales compensation plans, as follows:

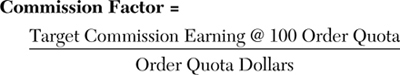

• Quota-based plans: In these plans, there is usually an order quota and a booking quota. The order quota usually serves as the basis for determining commission earnings. And the booking quota usually serves as the basis for the eligibility for noncash incentives, such as the quota club.

A commission factor can then be determined. The following is an example of the calculation of a commission factor:

Commission credit can be granted only for firm purchase orders procured by the sale representative and accepted by the company. The criteria for the acceptance of purchase orders is usually determined on a year-to-year basis.

Now that the commission formula is established, the commission payment structure can be triggered. Commission earnings are based on the order dollars generated by the salesperson’s efforts.

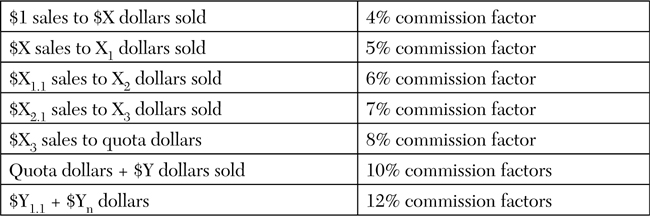

If the commission factor were calculated to be (using formula) 8%, then if an order is received for $10,000, the commission earned would be $800. Some organizations might set up a sliding scale to determine the payout commission amount, as demonstrated in Exhibit 7-3.

Exhibit 7-3. The Commission Earned Sliding Scale

The commission formula scheme is an escalating scheme geared to motivate the salesperson to increase sales order dollars to as high as possible.

Sales personnel are also assigned an individual booking quota. The booking quota can be the prime determinant for quota club participation and for any other noncash recognition awards. Booking quota credit can be given for the total contract quantity for the first 12 months of the contract.

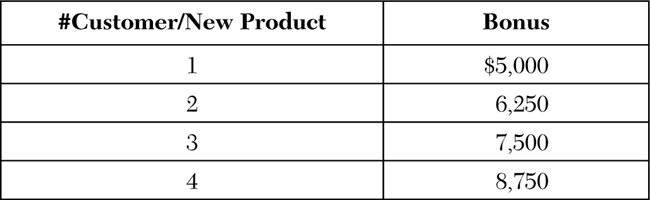

• New customer/new product bonus plans: Because the generation of new business is important to the company, a bonus for new customers and new products sold to existing customers can be made whenever certain criteria are met within a specific time period. The bonus quantity might need to be shipped to qualify for the new account/new product bonuses.

A schedule for the bonus element can be laid out as shown in Exhibit 7-4.

Exhibit 7-4. A Sales Bonus Schedule

A stipulation might apply as to which new product qualifies for this bonus.

• Shipment commission: An additional shipment commission can also be provided for a revenue-recognized shipment of product and spare parts per a predetermined schedule, as shown in Exhibit 7-5.

Exhibit 7-5. A Shipment Bonus Schedule

Shipment commissions are paid for shipments within a given yearly period.

• Split commissions: If the orders are booked in one territory and shipped from outside that territory, a formula can be set up to split the commissions. For example:

• One-third commission to salesperson in territory where order is placed.

• One-third commission to salesperson in territory into which product is shipped.

• One-third or any partial one-third commission to wherever the approval, sales liaison, or sales effort was made. The adjudication of this commission is usually left up to management.

• Draws: When circumstances warrant, a draw against future commissions may be approved by management. The draw is often set for a fixed period at a particular level, but usually at no more than 50% of year-to-date quota performance. The maximum level of the draw balance that will be permitted in the draw account is specified as to amount and length of time the draw can be outstanding. Then a stipulation can be made saying that the draw balance can be recovered based on a percentage of commission credits per month until 100% of the draw is recovered.

• Reserves: During any particular month, if the net commission results in a negative amount, the negative balance can be placed in a reserve account. Recovery is made at a certain percentage of the subsequent month’s commission until the reserve balance has been reduced to zero.

• Price changes and adjustments: If the price for any product units ordered by the customer changes, a quota and commission credit adjustment can be charged or credited to the sales representative who originally received quota credit.

• Commission recovery: If the customer or the company cancels any part of an accepted purchase order, the quota and commission and any bonuses for units not yet shipped can be charged back to the sales representative who originally received quota credit. Also, if a receivable on an account goes beyond 60 days (for example), a straight chargeback can be applied to the commission on those accounts.

• Exceptions: Sales and revenue resulting from accounts designated “house accounts” may not qualify for commission purposes. Each house account can be treated on an individual basis, with an appropriate sales bonus associated with it. Plan conditions, might state, for example, that house accounts cannot be included in quota assignments for certain specific accounts.

Accounting Control and Audit Issues

From an accounting control point of view, the following potential provisions of sales commission plans are important to understand:

• Commissions and bonuses will be paid upon the firm acceptance of a purchase order and revenue shipments.

• Commissions and bonuses can be paid in advance of the company’s anticipated receipt of revenue. Advanced commissions and bonuses are considered earned and vested only upon receipt of full payment of revenue on which they are based. Commissions and bonuses not earned as a result of an order cancellation, returned shipment, or billing adjustment must be refunded to the company.

• Commissions and bonuses can be calculated and paid monthly. Each month’s commissions are normally calculated monthly even if payment is not made. Each calendar month’s net commissions and bonuses can be paid by the end of the following month.

• The net dollar amount paid during a particular month can be (1) the sum of the positive commission and bonus dollars calculated for the previous month minus any negative commission or bonus dollars owed pursuant to the plan provisions and not previously deducted, (2) and/or minus any draw recovery, and (3) any amount recovered as an offset to a negative reserve balance. (A maximum incentive dollar amount payable under the plan can normally be stipulated in the plan.)

• As an accounting control, companies can reserve the right, in sales compensation plans, to make a fair and equitable adjustment to quota, commission, and bonuses where business clearly has been lost because of nonperformance outside the control of the direct sales employee. This is in spite of the best efforts of the direct sales representative to manage the situation.

• Under certain circumstances, the company can reserve the right, at its discretion, to reduce quota achievement or commission and bonus dollars below levels set forth in this plan. These circumstances might include but are not limited to the following transactions:

• Where profitability has been affected adversely by concessions

• Where normally required sales effort was not expended

• Where unusual assistance has been provided to the salesperson

• Where violations of good business practices or professional ethics occurred

• Each sales representative can be provided with a copy of the plan. The sales representative is expected to acknowledge receipt of the plan, read the plan, confirm his/her understanding by signing the plan, and then return it to their managers (all before any commission can be paid by the accounting department). Of course, the accounting department can make payment only subject to plan provisions.

• Contracts and purchase orders: A duly executed contract is often required for the acceptance of a purchase order. The contract should be referenced in each purchase order. A contract, even if a quantity over time is indicated, does not normally represent a purchase order. No quota credit is usually granted against contracts for purposes of determining commission payment amounts. Purchase orders need to be firm and in writing. If electronic media is used to transmit a purchase order, a written confirmation within 30 days (for example) might be required. In addition, for a purchase order to be accepted, it must specify the product, the quantity, the unit price, the extended price, and the requested delivery schedule. All these stipulations will need to be consistent with the terms of the underlying contract. Also, a provision can be included that if delivery on a purchase order extends beyond 14 months the commission credit will be granted only for units to be delivered within 14 months.

Other Salient Elements of a Sales Compensation Plan

Expense Allowances

Sales personnel are often required to travel as a part of their jobs. This travel might be part of their daily work routine or might cover longer distances that require them to be “on the road” for considerable periods of time. Per the U.S. tax code, this is a tax-deductible expense for the employee, if there is no employer reimbursement. But, most organizations reimburse the employee for these expenses.

Accountable and Nonaccountable Plans

If the employer reimburses employee business expenses, how the employer treats this reimbursement on the employee’s Form W-2 depends in part on whether the employer has an accountable plan.2 Reimbursements treated as paid under an accountable plan are not reported as pay. Reimbursements treated as paid under nonaccountable plans are reported as pay.

2 This section was adapted from IRS publications at www.irs.gov and http://irs.gov/publications/.

To be an accountable plan, the employer’s reimbursement or allowance arrangement must meet all the following conditions:

• Expenses must have a business connection; that is, the employee must have paid or incurred deductible expenses while performing services as an employee of the employer.

• The employee must provide adequate accounting for these expenses within a reasonable period of time.

• The employee must return any excess reimbursement or allowance within a reasonable period of time. An excess reimbursement or allowance is any amount that the employer paid the employee that is more than the business-related expenses that the employee adequately accounted for to the employer.

The definition of reasonable period of time depends on the facts and circumstances of the employee’s situation. However, regardless of the facts and circumstances of the situation, actions that take place within the times specified in the following are treated as taking place within a reasonable period of time:

• The employee received an advance within 30 days of the time the employee incurred the expense.

• The employee adequately accounts for the expenses within 60 days after they were paid or incurred.

• The employee returns any excess reimbursement within 120 days after the expense was paid or incurred.

• The employee is given a periodic statement (at least quarterly) that asks the employee to either return or adequately account for outstanding advances and to comply within 120 days of the statement.

If the employee meets the three conditions for accountable plans, the employer should not include any reimbursements in the employee’s income in box 1 of the Form W-2. If the expenses are equal to the reimbursement, the employee does not have to complete Form 2106. The employee has no deduction because the expenses and reimbursements are equal.

If the employer includes the reimbursements in box 1 of the Form W-2 and the rules for accountable plans are met, the employee should ask for a corrected Form W-2.

Even though the employee is reimbursed under an accountable plan, some of the expenses may not meet all three conditions. All reimbursements that fail to meet all three conditions for accountable plans are generally treated as having been reimbursed under a nonaccountable plan.

If the employee is reimbursed under an accountable plan, but the employee fails to return, within a reasonable time, any amounts in excess of the substantiated amounts, the amounts paid in excess of the substantiated expenses are treated as paid under a nonaccountable plan.

The employee may be reimbursed under an employer’s accountable plan for expenses related to that employer’s business, some of which are deductible as employee business expenses and some of which are not deductible. If the reimbursements the employee receives for the nondeductible expenses do not meet the first condition for accountable plans, they are treated as paid under a nonaccountable plan.

The deductibility for the company as a business expense depends chiefly on whether the payment is made under an accountable plan. There is a definite advantage from a tax perspective, for both the organization and the employee, to seeing that reimbursements are made under an accountable plan.

If the organization’s plan does not meet these conditions, as listed earlier, the plan is not an accountable plan. If it is not, the company has to pay FICA taxes on the reimbursement amounts paid to employees. For employees, the difficulty is having the reimbursements considered wages and then having to deduct them from their own tax returns.3

3 This section was adapted from IRS publications at www.irs.gov and http://irs.gov/publications/p463/ch06.html.

Travel Allowances

In practice, three main types of travel allowances are used: automobile allowances, company vehicles, and per diems.

Automobile Allowances

There are three basic types of reimbursement plans used for the accounting of automobile expenses:

• Actual expense method: In this method, employees are required to keep track of all expenditures related to their automobile and to report them periodically to their employer for reimbursement. This includes all the items mentioned earlier with regard to accountable plans. The items can include fixed expenses such as registration fees and variable items such as gasoline and oil. The total costs then have to be divided by the percentage of total usage of the automobile for business purpose versus usage of the automobile for personal purposes.

The advantage to this method is that it reflects the actual costs rather than estimated costs. The disadvantage of the method is that it is time-consuming and can be quite involved to keep such a complete record of expenses. Because the employee keeps these records, there may be a tendency to inflate the figures.

• Standard mileage method: The simplest and most common way to reimburse employees for their automobile expenses is to pay them a mileage allowance based on the number of business-related miles they drive.

Ordinarily, the employer uses the standard mileage rate established by the IRS each year (.555 cent a mile in 2012). However, the organization might pay employees a higher rate, so long as the rate is reasonably designed not to exceed the employee’s actual or anticipated expenses. In this case, the amount of expense the organization can deduct is the lesser of:

• The amount the organization paid under its own mileage allowance

• The government’s standard mileage rate multiplied by the number of business miles substantiated by the employee

The standard mileage rate is reviewed and changed each year by the IRS. You can find this information at www.irs.gov.

The main advantage to using the standard mileage method is clearly its simplicity. The record keeping is limited. Further simplification is provided in that the mileage rate is not subject to dollar caps or the special rules that apply if qualified business use does exceed 50% of total use. The major disadvantage to the standard mileage method is that it might not cover all the costs of driving the automobile. Fixed costs such as depreciation are not taken into account. The employee may be able to calculate these additional costs and deduct them as expenses from their taxes separately.

• Fixed and variable rate (FAVR): This is an allowance the employer may use to reimburse the employee’s car expenses. Under this method, the employer pays an allowance that includes a combination of payments covering fixed and variable costs. For example, a cents-per-mile rate may be provided to cover the employee’s variable operating costs (such as gas, oil, and so on). A flat amount to cover your fixed costs (such as depreciation, lease payments, insurance, and so on) can also be added on. If the employer chooses to use this method, the employer must request the necessary records from the employee.

Use of Company Vehicles

Some companies provide their sales personnel with company vehicles. If the company vehicle is used entirely for business purposes, the employer might be able to deduct the costs of the vehicle as a business expense. If the employee also uses the company-owned vehicle for personal use, however, the accounting treatment differs. The employee personal use portion of the vehicle’s operational costs becomes a benefit to the employee and is considered income and is taxable. This will increase the record-keeping requirements, in that the employee will have to maintain a log of all travel in the company vehicle indicating whether each trip was for a business or personal reason.

For company-owned vehicles, the personal-use portion is calculated via one of three methods: cents-per-mile rule, commuting rule, and lease-value rule.

Cents-Per-Mile Rule

Under the cents-per-mile method, you multiply the current mileage rate ($.51 for January through June 2011; $.555 for July through December 2011) and .555 per mile in 2012 times the personal-use mileage. To use this method, you must, among other requirements, use the vehicle more than 10,000 miles per year, and the vehicle must be valued at less than the maximum permitted value when placed in service ($15,300 autos, $16,000 truck or van for 2010) and also meet the regular use requirements.

Commuting Rule

Valuation for the commuting rule is based on $1.50 per one-way commute (per employee). To qualify for this method, the employer must (1) provide the vehicle for bona-fide business purposes and require the employees to commute in the vehicle and (2) establish a written policy stating that the employer does not allow the vehicle to be used for personal purposes other than for commuting.

Lease-Value Rule

Most employees can qualify under the lease-value rule based on the fair market value of the vehicle. The fair value is equal to what it would cost to lease a similar vehicle from a third party, known as the annual lease value. To make this calculation easy, the IRS provides an annual lease value for vehicles based on the vehicle’s fair market value. The vehicle’s fair market value can be determined from any number of Web sites or automobile appraisers. The best source is Kelley Blue Book’s Web site: www.kbb.com. Once the vehicle’s fair market value is determined, the employer can use the annual lease value table provided by the IRS in Publication 15-B.

After the personal-use percentage and the annual lease value have been determined, the two items are multiplied together to determine the taxable value of the benefit. The taxable value of the benefit is subject to both income and payroll taxes. The value of the benefit must be increased to cover the payroll tax liabilities. This increased value should be shown on the employee’s Form W-2 at the end of the year, because the employee will be subject to taxes on the value of the benefit. It is advisable that these calculations be done in advance so that additional income tax withholding can be taken out of the employee’s regular pay.

The key thing is good record keeping, and it is essential to avoid understating or overstating the employee’s tax liability.

Per Diems

A per diem allowance is a fixed amount of daily reimbursement the employer pays the employee for lodging, meals, and incidental expenses. Federal government per diem rates can be figured by using one of the following methods:

• The regular federal per diem rate: This rate varies by location. It includes all the lodging, meals, and incidental expenses. You can find these per diem rates online at www.gsa.gov/portal/catagory/100120.

• The standard meal allowance: The standard meal allowance alternative is used when the employee does not have any lodging expense, such as when the employee stays in a company-owned accommodation or with relatives. It covers only meals and incidental expenses. You can find calculations for this category of expenses at the IRS Web site.

• The high-low rate: A simplified computation with one rate for high-cost cities and another for regular locations. The amount changes each year. You can find the current amounts and cities in IRS Publication 1542 (www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p1542.pdf).

Commission Accounting

We now turn our attention to commission accounting.

Usually, commission accounting activities are performed with add-on commission accounting software, many of which are available. Examples include the following:

• QCommission

• Glocent

• Sales Wand (for SAP only)

• Account Pro

• Actek ACom

• Maestro

• TrueComp

• CompensationMaster Commission Planner

• Exaxe

• planIT Sales Compensation

• GreenWave

This is just a partial list; many others are available.

These applications improve sales productivity by centralizing and automating commission-based sales compensation plans. The commission accounting applications allow performance tracking, reporting, and the calculation of commission compensation based on performance variables and also the management of key dates in the company’s sales/compensation cycles. Software applications can also assist in the management of regulatory requirements as it pertains to the sales compensation programs. The primary advantages of these applications are accounting integration, commission calculations, commission splits, quota management, and chargebacks.

The main operational functions of the software applications are transaction processing, file maintenance, reporting and inquiry, and time-bound processing.

The commission accounting applications should include commission compensation administration features such as the following:

• Commission posting from accounts receivables and order entry into the commission accounting software

• Transfers of sales commissions to accounts payable and the payment of sales commissions through accounts payable

• Options for transferring summary or detail information to accounts payable

This chapter focused on just the accounting-related and finance-related issues of sales compensation program design. We used a hypothetical sales compensation plan to discuss the key financial and accounting issues. We also looked at various IRS rules and regulations with respect to factors that affect the design of sales compensation programs. This chapter also described commission accounting systems and various sales compensation payment types (allowances).

In sales compensation program design, another key implication is equally important: The program needs to be aligned with the organization’s overall strategy, and especially the sales and marketing strategies.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Quota-based plans

• Base, bonus, and commission plans

• Commission factor

• Expense allowances for sales personnel

• Automobile allowance reimbursement plans

• New customer/product bonus plans

• Shipment commission

• Split commission

• Quota clubs

• Draws

• Reserves

• Commission accounting

• Gross margin versus revenue as a triggering mechanism