2. Business, Financial, and Human Resource Planning1

1 Adapted wholly or partly from a paper written by Biswas, B.D., and Hestwood, T., “Human Resource Planning and Compensation: A Developing Relationship.” Conference presentation made at National Conference of the American Compensation Associates 1979.

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Explain the connections between business planning, human resource planning, and compensation planning

• Develop the need for planning

• Examine the concept of strategic planning

• Explore the connections between strategic planning and operational planning

• Discuss the concept of HR planning

• Review an integrated HR planning process

• Discuss the concept of organizational planning and design

• Develop the connections between HR and compensation planning

• Explain the concept of talent management

This chapter deals with the strategic concept of planning. Effective compensation and benefits program design—from an accounting and finance point of view—requires a solid planning foundation.

Finance and accounting departments usually are the operational guardians of the organization-wide planning activities. Therefore, before delving into the components of compensation and benefits program design (from an accounting and finance perspective), it is important to discuss the concept of planning and how it ties into human resource (HR) planning and then compensation and benefits planning.

Integrating HR, compensation, and benefits activities into strategic financial and operational plans is a key first step for the integration of the two disciplines (HR / compensation and benefits and finance / accounting). Therefore, this chapter explores these connections.

Business and financial planning, as well as HR and compensation planning, have not traditionally been thought of as codependent functions. This is reflected in how HR departments normally are organized. Even in organizations that usually have an HR planning function, it is normally teamed with organization planning and development function. This is because the organization planning and development is often commissioned to conduct organizational effectiveness studies. Compensation is a separate entity. In addition, experience suggests that even informal links between the two functions are few and far in between. Compensation specialists and financial or even HR planners rarely work together on projects and tasks.

However, both the planning and compensation functions can gain by being better aligned. This chapter looks at the reasons why planning is necessary. The focus then turns to a review of a standard structure for strategic business planning and the related strategic and operational financial planning. The discussion then suggests an HR planning model that flows from the inputs of the strategic and operational financial plans. This chapter also explores the specific benefits a total compensation system can derive from the planning efforts. The chapter ends with a look at how compensation can contribute to the overall planning effort.

The Overall Planning Framework

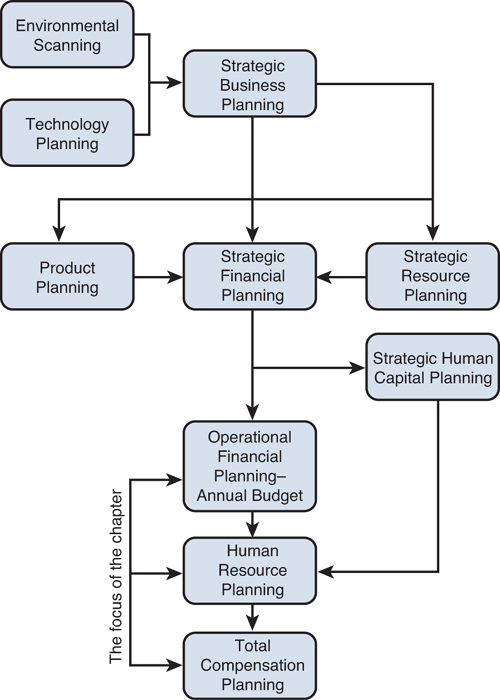

Exhibit 2-1 shows a flowchart of planning activities, and is a macro view of the planning process. This overall planning framework identifies the focus of this chapter.

Exhibit 2-1. A Conceptual Framework for the Connections between Strategic Business and Financial Planning and HR and Total Compensation Planning

The Need for Planning

Organizations know that success requires planning with regard to both physical and financial resources. (In economics terms, these are the factors of production.) To state an obvious example, electric-generation companies must now plan more carefully than ever to ensure an adequate supply of coal at the right time and place. Electric generation plants require large quantities of coal to operate. It’s not just shortages that promote planning, it’s the complexity in the form of the global nature of business, of government regulations, of the exponential growth of technology, of human capital challenges, and all the other interests of various stakeholders. Managing the interconnectivity among these varying forces clearly requires planning.

Planning entails many dimensions, each connected to the other in an integrated approach to planning. Exhibit 2-1 suggests a form of this integrated approach. The exhibit suggests that clear connections do indeed exist between these planning processes. Strategic planning or longer-term planning is important, but this activity (at least an in-depth discussion about it) is beyond the scope of this chapter. The discussion here is limited to the connections between operational financial planning and HR planning and the subsequent connections to total compensation planning.

Strategic Planning

Let’s briefly consider strategic planning here. Strategic planning refers to an organization’s process of defining its strategy, or direction, and making decisions about allocating its resources to pursue that strategy. The strategic plan identifies and analyzes the current status, objectives, and strategies of an existing organization to determine the direction of the organization. It is necessary to understand the organization’s current position and the possible avenues through which it can pursue alternative courses of action. An organization looks at strategy from a long-term perspective. Therefore, strategic planning is considered a process for determining where an organization is going over the next three to five years (long term).

When looking at the longer term, organizations examine existing or perceived strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities (SWOT). Information about the future business and social environment the organization operates in is analyzed in connection with the marketing, production, and research capabilities, which then leads to strategy development covering the following issues:

• Vision

• Mission

• Values

• Strategies

• Goals

• Programs

• Objectives

• Resource allocation

Business plans are derived from strategic planning in terms of the products or services to be produced and the materials, people, and facilities necessary to produce them. All of this is converted to the language of business: finance and accounting.

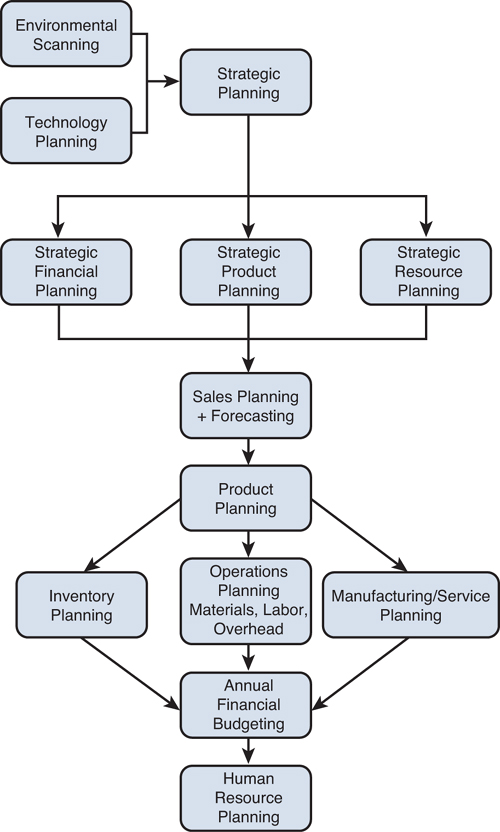

An integral part of the strategic business planning process is the follow-on strategic financial plan, which codifies the strategic plan in monetary terms over the same long-term time horizon. The strategic financial plan then forms the basis for the short-term operational financial plan, often called the annual financial budget. Thus, strategic financial plans become the triggering point for the annual operational financial budget planning exercise. Operational financial planning is also often called profit planning. Exhibit 2-2 shows these connections in the planning process. It also illustrates how strategic financial planning flows through to the operating profit plans of an organization.

Exhibit 2-2. The Planning Connections

The annual financial budget or the profit plan is important for many reasons, including the following:

• It is a means of communication throughout the organization.

• The financial budgeting process facilitates management planning for resource usage.

• The financial budget is a mechanism that assists with the most efficient allocation of resources within an organization.

• It also assists in uncovering potential trouble areas, before they happen.

• The financial budget assists in coordinating the varied activities within an organization into an integrated focused effort that is in sync with the strategic business plans of the organization.

• The financial budget structure lends itself to the tasks of monitoring and controlling, which are necessary to ensure that progress is measured and all the required activities within an organization are on track.

Therefore, strategic and operational financial planning is certainly a key success factor for any organization. Within this context, the focus now turns to HR planning and the subsequent total compensation planning.

HR Planning

The HR function is on a continual talent hunt for the right human resources at the right times and the right places. This is similar to resource acquisition and consumption in other areas throughout the business world. All business functions, including the HR function, face supply issues and therefore must plan for such. This section covers a few of the reasons why such planning is vital.

First, organizations require a sufficient number and quality of the “right” talent (talent management) available to meet future organizational needs. With regard to this requirement, a number of factors make HR planning a necessity:

• Technical obsolescence and associated technological innovations: In many technical fields, a person’s professional knowledge can become obsolete within five years. Firms that require the development of new or expanded technology must constantly retrain and reeducate their employee base. Of course, talent acquisition, training, and education take time. To have that time requires HR planning and a global view of the HR capital asset or resource.

• Scarcity of the right type of talent: In some occupations and areas, the unemployment rates for specifically skilled professionals is nearly zero. And this is in spite of the high overall current unemployment rates and the increasing numbers of structurally unemployed individuals. Managers and skilled professionals in such fields as specialized engineering programming, robotics, and biotechnology are still in short supply. Shortages in specific types of needed talent are going to continue for some time to come.

Organizations confront some interesting attitudinal problems with an issue like this. Consider this analogy: Many motorists, as demonstrated by their driving patterns, still find it hard to believe that there is a diminishing supply of fossil fuel resources in the world. Similarly, many managers and HR professionals find it difficult to believe that there might be a shortage of the right talent to fill specific openings. If these shortages are real then organizations should be planning for the optimization of human capital resources.

• Lack of an adequate level of geographic mobility: Because of the employment needs of spouses and quality-of-life considerations, more people are unwilling to relocate. Because of this inability to motivate employees to relocate, the supply of qualified candidates may be inadequate to meet the needs of many organizations.

• Transferability of skills: As long as talent shortages remain and technological innovation continues, professionals in those fields will find it easier to transfer their skills and talents from company to company. Companies cannot count on people spending their whole careers in one organization.

Second, organizations must identify problems that are hindering the optimal use of human resources, leading to organizational ineffectiveness. To meet the needs of the future, employee and organizational effectiveness needs to be improved at every possible opportunity. The planning process provides an opportunity to identify shortages of skills, overstaffing or understaffing, and other human resource problems.

Third, HR planning integrates the goals and actions of the disparate HR functions and enables HR management to allocate resources to the functions capable of contributing most to the organization’s needs. The activities of the separate functions (compensation, staffing, training, and so on) should be based on the objectives of the business. For example, recruiting may be rejecting applicants for technician jobs without knowing what training could be done in-house to make technical employees more effective and in tune with the current business needs. Compensation may be developing a system of flexible benefits, even though the real need is extra dollars of base pay to help get people in the door and to keep them there. Planning facilitates the use of a “systems approach” to HR management.

The last reason for HR planning is that it creates the ability to respond quickly to unexpected business and financial changes, such as mergers, acquisitions, financial consolidations, and product demand.

An Integrated HR Planning Process

Financial planning, HR planning, and compensation planning have a lot to gain by being more closely associated. Therefore, HR planning is the process by which an organization forecasts the future HR requirements of the organization and then develops and implements policies and programs to meet those requirements.

Now that we have established the need for HR planning, let’s expand on the definition of the term and look at a model for the process.

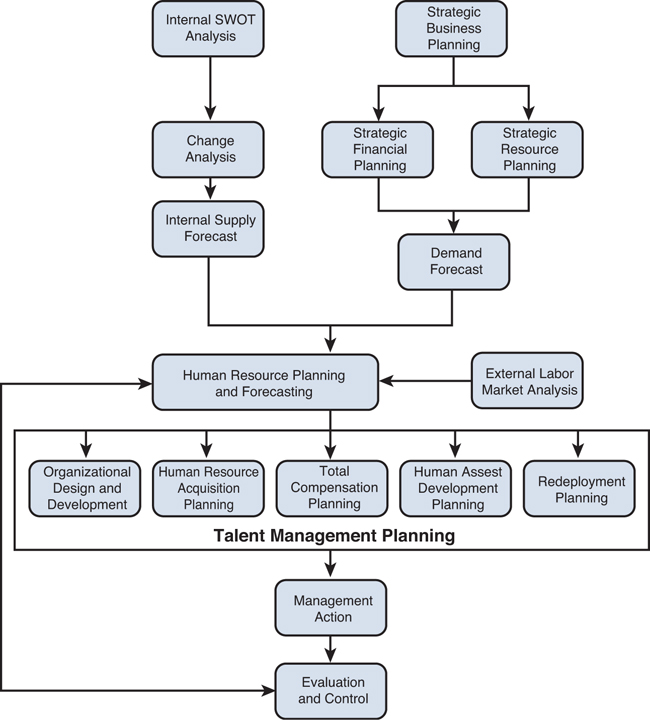

HR planning is the process by which an organization forecasts the future HR requirements of an organization and develops and implements plans, policies, and programs to meet those requirements. This definition emphasizes the integration of HR plans with the development of the HR programs necessary to achieve those plans. The model of the planning process shown in Exhibit 2-3 illustrates this approach.

Exhibit 2-3. An Integrated Human Resource Planning Process

The model consists of four major components. The first component is the process of developing future HR requirements—the true planning part of the process. The second component is the establishment of HR policies and programs necessary to achieve those plans. We call this step talent management. The third component comprises the actions taken by HR professionals and managers to implement HR programs developed in the second component. The last component is the evaluation of the success or failure of the actions taken.

Demand Planning

HR plans are formed by comparing projections of expected demand for the HR talent (the right side of the model) and the potential supply of the talent (the left side of the model). Forecasts of demand are not going to proceed without an analysis of the capabilities of the existing workforce to meet them.

There is a great deal of variability among organizations in the procedures used for defining the HR requirements. Some companies have a team at headquarters that determines the needs by means of quantitative forecasting. Other organizations leave it up to division or department managers to forecast and plan their talent needs based on unit objectives and plans. The financial planning staff then totals the projections from these departments to develop an organization forecast.

Note that in this planning process even though the number of employees may remain constant based on current conditions, the composition of the workforce might need to be changed because of current business conditions. This might then require a change in the HR programs.

Organization Design and Planning

The next step in the planning process is organization design and planning. Organization design and planning is a process by which tasks are defined and grouped into positions and jobs and then integrated into an organization’s structure (thus enabling the achievement of future business objectives). In other words, managers need to outline not only the number of employees they are going to require but also the required knowledge, skills, abilities, behavioral dimensions, experience levels, and competencies. Managers also need to develop the optimum organization structure based on guidelines provided about work levels and spans of control. Organization design and planning activities are becoming an integral part of the systematic talent management process. However, the trend has not been widely established, and many differences among organizations still exist as to what organization planning and development means and how it is implemented.

Also, the word competency has recently entered into the lexicon of HR management. In practice, though, there are multiple definitions and interpretations of this word. From among them all, the definition that makes the most sense states that competencies are the optimum set of knowledge, skills, abilities, and associated work behavior necessary to achieve the company’s strategic and operational business objectives.

Organization design and planning is introduced into the HR planning process to deal with a common deficiency of many planning processes: the failure to define talent needs in terms specific enough for use by all the stakeholders: supervisors, managers, and the various HR functions. Talent forecasts are often stated only in quantitative terms. (For example, the marketing department will need 20 new people, and the accounting department will require 10 new people.) To ensure that a sufficient degree of detail is made available, managers must be asked to conduct organization design and planning exercises.

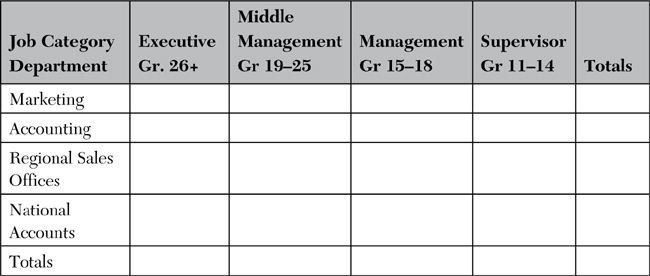

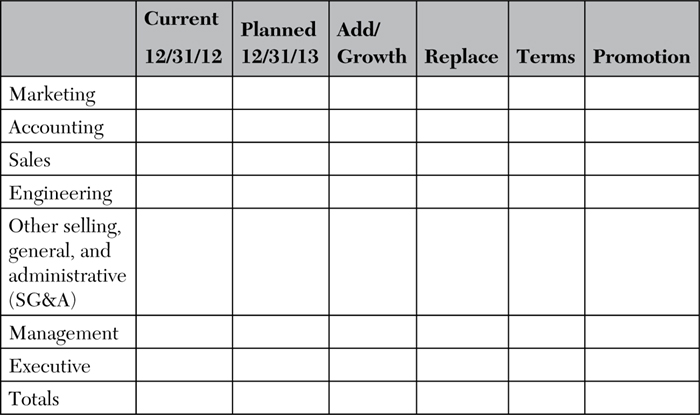

Forecasting Demand

Exhibit 2-4 presents a format for the development of a talent demand forecast—the next step in the planning process. This needs to be completed after the organization design and planning step. The exhibit presents future talent requirements, by department, for major job categories and job grade or salary levels. Special knowledge, skills, ability, experience, and competency requirements are noted in footnotes of the exhibit. An organization chart may be required as well. Large organizations may want geographic breakdowns or have other specific data-clustering requirements.

Exhibit 2-4. 2013 Projected Additional Staff Requirements

Supply Planning

Let’s turn now to the supply side of the model. In this part of the model, we examine the quality and capabilities of the current talent pool. This is compared to the talent requirements needed over the forecast period. The comparative analysis will determine whether the workforce can meet the needs of the future.

We should not assume that the current talent pool is performing adequately or that it will meet future job requirements. One way to examine the quality and capabilities of the current talent pool is to conduct a talent review. The talent review is a systematic assessment of the qualifications and skills of individuals in the organization and the potential of those people to fill higher-level jobs. It involves questions such as these: Is the department meeting its goals and objectives? Are present incumbents performing adequately? If not, what actions can be taken? Are there enough resources in the current talent pool to fill key positions if current incumbents leave? Is our current talent pool being adequately trained to do their jobs in the future?

Often, information useful to compensation comes out of these discussions. Examples include information about perceived job-classification problems or the problems associated with high-potential employees, who are not being paid in line with market rates. Compensation specialists should become part of the team that conducts the talent review to ensure that issues affecting them are fully appreciated.

The next step on the supply side of the model is to determine the talent changes expected over the course of the planning cycle. In this part of the process, you always examine key segments of the talent pool. The analysis can be extended to the total talent pool if the future supply of workers is unstable. Forecasted changes include terminations, retirements, and layoffs. The data on these changes can be derived, especially in the case of terminations, from an extrapolation of historical trends in turnover grouped by termination reason. In the case of retirements, recent company experience can guide you. The talent changes should be projected by location, division, and job-family categories.

To integrate the potential internal supply information with the demand requirements, the information from each department or division is summarized on a table such as the one presented in Exhibit 2-5.

This exhibit shows data for each talent group, the current staff, the planned talent pool, additions to the pool, and the number of replacements that may have to be hired to reach a total year-end talent level. To provide a complete picture of the talent situation, each department or division can provide a narrative summary of the HR problems and challenges they anticipate confronting over the forecast period. They should explain how they plan to deal with the problems. By combining qualitative and quantitative information in this fashion, the organizational planning process can better meet the needs of all HR functions and, of course, those of the business as a whole.

External Labor Market

Organizations must also consider the projected availability of the right type of workers in the external labor market. The unemployment rate for different kinds of workers, labor force participation rates, and the external demand for similar skills and experiences can all have a major impact on an organization’s HR plans. The external dimension will affect the organization’s ability to attract new talent. The conditions in the external labor market affect an organization’s turnover. The more opportunities there are in the external labor market, the higher the internal turnover. Therefore, organizations must keep track of the external market because it can affect the internal talent tool. This data is often available in local newspapers. For example, a manufacturer studied labor market conditions in a Southeast Asia location and found them ideal. There was a high rate of unemployment among skilled workers and a good labor pool to draw on. When the manufacturer opened a plant in that city, they found that other firms had also looked at the favorable conditions there and had decided to exploit the same location. The end result was that when all of these new businesses arrived, an acute labor shortage developed.

Planning information is gathered at different levels, in different degrees of detail, and over different time frames based on the type of organization. For example, in industries with relatively stable product markets, such as the airline industry, planning can be carried out on an overall company level without significant problems in the accuracy of the information. In more volatile industries and where the information needs to be specific, such as the technology sector, planning is more likely to be initiated at the division or department level. Divisional and departmental plans are rolled up to derive the company total.

Management Action/Evaluation and Control

Before we look at the relationship of planning to compensation, let’s look at the two last segments of the model. Management action is the implementation by line managers of the programs developed by the HR department. The most sophisticated programs in the world will not be successful if improperly implemented and administered. The commitment of top management, the involvement of line managers in policy and program development, and the clear and careful communications are still the most important elements for the successful implementation and administration of programs.

The final step in the model is the evaluation of the contributions that each HR function makes to the achievement of the talent management goals of the business. Data needs to be collected on the actual achievement results compared to the objectives that were set in the planning process. This is where HR effectiveness measures come into play. Chapter 11, “Human Resource Analytics,” discusses these measures in more detail. Procedures should be developed for taking corrective action for deviations from planned objectives.

The theory of constraints can be an effective method used during the evaluative phase. The theory of constraints calls for determining the weakest links and then focusing corrective attention on those areas.

HR Programs

The relationship between HR planning and the functional areas of human resources (compensation, benefits, recruiting, training, and employee services) can be clearly discerned. Recruiting uses the information to plan programs such as college recruiting, difficult recruiting efforts, and major recruiting campaigns such as those necessary to staff new programs, plants, or divisions. Training and development uses it to identify the kinds of talent that are being added to the organization and the training and developmental needs the talent pool is likely to require. The relationship between planning and compensation is less obvious and is the one examined in some detail in this chapter.

Compensation

To start our look at this relationship, let’s identify the major compensation activities. We will then discuss those components that can derive benefits from HR planning. The compensation activities that have been identified are as follows:

• Program development: This is the design of salary ranges, salary-increase guidelines, incentive plans, and other techniques used by managers to determine individual employee salaries.

• Program costing: The next chapter covers this important component.

• Job analysis and classification: This is the process companies use to ensure internal equity or pay consistency within the organization.

• Program administration: These are the processes used by managers and HR departments to administer salary programs.

• Executive compensation program development: These are special compensation programs designed exclusively for the senior management in an organization.

Program Development

Compensation departments engage in some planning activities when developing salary programs. Typically, compensation planners collect data on the rate of inflation, changes in the cost-of-living indices (a measure that is used to gauge changes to the inflation rate is the change in the cost-of-living index), and union settlements. Compensation planners use such data to develop salary programs. However, most of the planning activities done currently are for the short term, normally a year. Short-term plans by their very nature are a response to immediate problems such as turnover, complaints about inflation (not in the USA now), or recruitment difficulties. One cannot ignore these immediate problems, but it is also important to analyze the longer-term implications of the actions taken.

An example of inadequate planning in program development is evident in the experience of a West Coast company. Although overall market average salaries for highly skilled engineering personnel in the labor market were increasing, the salaries of new college engineering graduates were not moving as fast as those in the general market because of the relatively high number of unemployed fresh college engineering graduates. Reacting to a short-term problem, the company decided, therefore, to move their range minimums less than the midpoints and maximums to control the cost of adjusting the salaries of employees low in the range. The company should have examined the future long-term trends in the external labor market by looking at long-term surveys of business activity. Had they done so, they would have found that the situation would reverse in the near future and that there would be a growing shortage of the specific types of engineers the company needed and that hiring salary rates would go up. Several months later, the failure to adequately adjust range minimums made it difficult to hire new college graduates in engineering. So, the company had to make reactionary mid-year salary-range adjustments. (Note this example is from a situation observed a few years ago.)

Information about the types and numbers of employees who will be added to the organization is also useful in developing increase guidelines and salary ranges for different job families. For example, suppose that your firm will increase its number of experienced engineers by 5% next year. The unemployment rate for those specific engineers is near zero, and turnover in your firm is significant. Even though your firm is already paying above market rates, you might have trouble finding and absorbing a large number of engineers without salary-compression problems.

Salary-compression problems occur when new employees come in at salary levels that put pressure on the salaries of existing employees. Under these circumstances, an organization will likely have to allocate more dollars to the engineering salary program than to the other programs by designing more liberal salary-increase guidelines and making bigger range adjustments for the engineering job family. If these additions are unknown (and therefore not being planned for), the organization might find it hard to attract the talent it needs without causing serious internal compensation problems.

The HR planning process can also provide information about jobs that are becoming more important or less important to the organization because of changes in the nature of the business. Compensation specialists can then be sure that important jobs are being included in benchmark job samples used to measure external competitiveness. For example, an international biotechnology company is planning to become more involved in development of genetic engineering solutions for medical technology. Because of the plan, genetic engineering specialists should be included in salary surveys and the resulting information considered in the design of the engineering salary program.

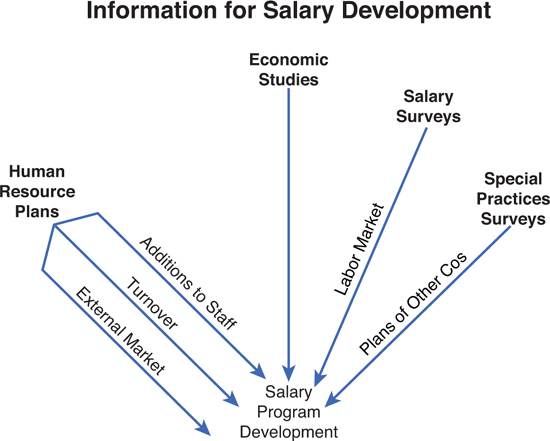

In a rapidly changing environment, organizations need to supplement normal sources of compensation information such as salary surveys and studies of expected salary changes in other organizations with information derived from the HR planning process. Exhibit 2-6 illustrates this concept. The most important information from the planning process is information about additions to staff, turnover statistics, and information about the future demand for talent from the external labor market.

Exhibit 2-6. Information for Salary Development

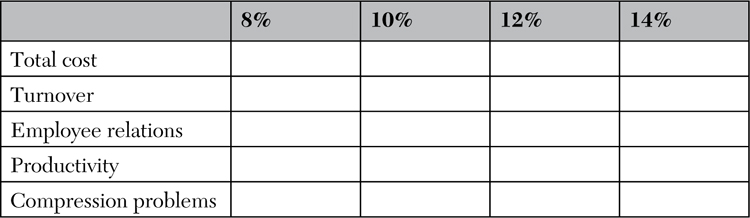

Ideally, compensation specialists need to be able to simulate the future consequences of their pay programs. Exhibit 2-7 illustrates in simple terms this kind of analysis. If the average increase is 3% rather than 5%, the consequences in terms of cost and turnover should be projected. The impact of change in economic conditions might be examined in a similar way.

Exhibit 2-7. Consequences of Salary Increase Alternatives*

* Numbers would be placed within each cell.

Job Analysis and Classification

Analyzing, describing, and evaluating jobs is probably the most time-consuming of all compensation activities. Moreover, it is often done under time constraints that make a thorough and well-prepared analysis difficult. Many times, however, the last-minute requests are not the result of last-minute decisions. They often were approved months ago; it’s just that the manager has an immediate and pressing need to hire and promote someone. Therefore, they need the compensation department to classify the job immediately to determine the appropriate salary level.

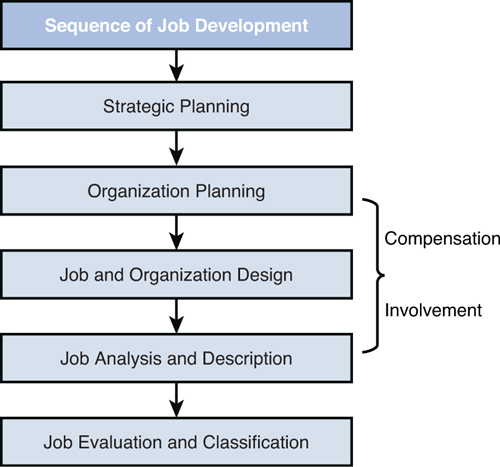

How does one deal with such crises? First, compensation specialists need to be involved in the HR planning process through participation in organization planning and effectiveness studies and, more important, in organization design decisions. If compensation specialists have assisted managers in organization design decisions, they will be in a much better position to accurately and quickly describe, evaluate, and market-price the jobs. They will not have to go over the rationale behind the creation of each job, and they will understand reporting relationships, skill, knowledge, abilities, and competency requirements. Exhibit 2-8 shows the sequence by which jobs are developed and where further involvement by compensation specialists fits into the process.

Exhibit 2-8. Sequence of Job Development

Organization Planning and Design

Organization planning is distinguished from job and organization design mainly by the detail of the analysis undertaken. Organization planning attempts to define job and organization needs for the future and, consequently, must be quite general in nature. Job and organization design, in contrast, deals with the here and now and requires decisions on specific work assignments and reporting relationships.

There is no right way to design an organization. The old organization norms, which suggested one supervisor for every seven subordinates (span of control) and clear distinctions between the responsibilities of line and staff, are no longer adhered to strictly. Although there is no one right way, there are ways of organizing that are more effective than others depending on the stability of the environment in which the organization functions, the type of technology, and the talent profile of the organization. For example, if a firm (or a division within a firm) uses a process production technology, has a stable product environment, and has relatively little need for high individual initiative and creativity, it should have a traditional, mechanistic type of organization. A flexible and more complex organization requires the reverse. These are extremes in a whole continuum of options, but they are the types of issues the organization has to address. Exhibit 2-9 illustrates these considerations. The compensation function may be the most logical area in which to facilitate organization design activities because it is the repository of information on jobs and job relationships.

Exhibit 2-9. Compensation Issues to Be Examined in a Talent Review

• Competitiveness of salaries of key people

• Attitudes of key people toward the compensation program

• Administrative problems of the compensation program

• Ability and willingness to pay for performance

• Future compensation issues: compression, reclassification, and so on

By being involved in job and organization design activities and having a better connection to the planning process, compensation specialists can be more effective and responsive in carrying out job analysis and classification responsibilities. Job analysis and classification is often a necessary activity to establish appropriate salary levels within an organization.

Program Administration

Pay programs are required to motivate the organization’s talent perform at superior levels, to attract and retain them, to be legally administered, and to be structured within the organization’s ability to pay. There are various ways to measure the achievement of these goals, such as examining salary-related turnover, looking at the distribution of increases in relation to performance, and measuring direct compensation costs as a percentage of some indicator of organization success such as revenue or other key financial ratios (a subject to be discussed in Chapter 11). Although useful, where these measures fall short is that they do little to help proactively anticipate problems. Employees do not terminate the minute they perceive a problem. The talent leaves when they think there is no possibility for any corrective action for their concerns. When action is actually taken, it is often too late to modify a program or to address pay inequities with large salary adjustments.

The talent review portion of the HR planning process can also contribute information about attitudes toward program administration that will help compensation specialists anticipate problems. The talent review and assessment can generate a wealth of information. However, for the review process to serve this purpose, it must be structured to elicit relevant information. Exhibit 2-9 outlines some of the issues related to compensation that you might address.

Executive Compensation

Executive incentive plans should be tied to the planning activities of the business. As the needs of the business change, so also should the criteria for payments under the incentive plan. With regard to business plans, in one year the major concern may be market growth, in another year profit growth may be the primary focus, and in yet another year cost control may be the emphasis. Unfortunately, many executive incentive plans continue to pay out on the same financial results year after year, with earnings before interest taxes depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) being the most common measure of financial performance used in incentive plan design. The measures used are also those that are commonly used in financial analysis and are part of both internal and external financial reporting systems. The tendency is to apply measures that are conveniently available and conventionally used. Instead, the goals chosen for incentive rewards should emphasize the goals of the business as reflected in short- and long-range business plans, not just those traditionally used in financial analysis and reporting. By obtaining information from the planning process as described in this chapter and finding out what the organization’s key success factors are from both the long-term and short-term perspective, organizations can develop executive incentive compensation triggering measures. Short-term, long-term, and value-enhancement measures should all be considered. Designing executive incentives only around short-term success measures can result in attempts to do earnings management under the accrual accounting structure. There needs to be more of an emphasis on long-term goals in executive incentive plans. Strategic measures that focus on sustained value creation should figure prominently in executive incentive compensation design. Chapter 4, “Incentive Compensation,” explores the finance and accounting implications of incentive compensation program design.

What Can the Total Rewards Function Contribute to the Strategic and Operational Planning Efforts?

The total rewards function not only receives benefits from planning activities described in this chapter but also provides valuable inputs to the planning process.

It can provide information in the form of an accurate and comprehensive system of job descriptions, job levels, and classifications. Effective organization planning and design relies on the job-classification system because job classifications provide the framework that management uses to establish job relationships within their operations. The job-classification system also provides a foundation for career planning and internal promotional opportunities by establishing a sequence of jobs by which internal talent mobility is facilitated. In addition, the classification system serves as the basis for HR planning, both from a qualitative and quantitative point of view.

The compensation function is usually the custodian of the job-classification system. So, developing the most appropriate job-classification system, maintaining it, and communicating it effectively is a key way in which the compensation function can contribute to the organization-wide planning effort.

The second area by which the compensation function can help planning is in the design, development, and administration of an effective performance management process. The mechanism to make decisions on deviation from business plans on a qualitative (and sometimes quantitatively) basis is the performance management process. The compensation function is often the custodian of this critical activity. An effectively designed performance management process should be able to facilitate constructive dialogue between management and the employees they manage.

The third area of contribution to the planning process is salary costing and budgeting. Employee compensation cost outlays represent a significant resource-allocation item in the financial structure of most organizations. In some organizations, such as service organizations, employee-related expenditures are the highest allocation item. Therefore, the compensation function activities to accurately cost programs and forecast expenditures are an organization-wide strategic imperative. This becomes crucial when one considers that employee expenditures are considered to be fixed expenditures in most cases. So, the compensation function needs to develop and maintain effective mechanisms for monitoring compensation expenses not only against budgets but also against other key relevant financial indicators of organizational success. Compensation specialists should implement cost monitoring systems that can serve an important role in business planning efforts.

This chapter stressed the importance of planning as we explored the connections between strategic business planning and operational financial planning. The chapter also looked at the connections between operational financial planning and HR planning. We then reviewed a detailed model for HR planning. The chapter then took a closer look at the relationships between financial and HR operational planning and the compensation function, ending with an exploration of the contributions the total compensation function can make to add value to the corporate-wide planning effort. The chapter concluded by reviewing how the compensation function can contribute to the organization-wide planning effort by taking on the task of providing timely and accurate financial plans and forecasting on total compensation expenditures. The next chapter explores this last point in more detail.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Talent management

• Organization planning and design

• Human resource planning

• Compensation planning

• Operational planning

• Supply planning

• Forecasting demand

• External labor market

• Job analysis and classification

• Program administration

Appendix

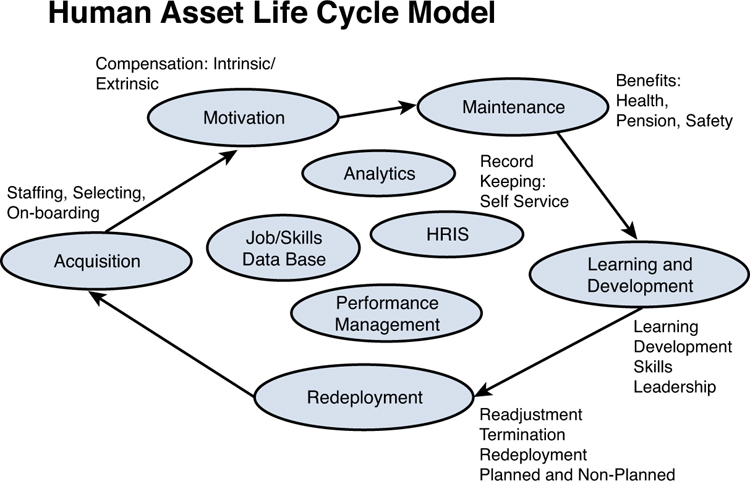

Exhibit 2-10 presents another strategic model for the HR planning process and the positioning of compensation and benefits planning within it.

Exhibit 2-10. Human Asset Life Cycle

This model suggests that human capital investments can be considered capital expenditures and as such, an organizational asset. This is a recurring theme in this book.

If you then consider human resources as assets like all other assets, they also have life cycles. This model depicts a life cycle view of human resource assets.

Just like other assets, the human capital assets of an organization are acquired, motivated (specifically in the case of human resources), maintained, developed (for improved productivity) and redeployed to other effective uses when current effectiveness diminishes. The current functional activities have been mapped into the changed paradigm in the model.

Notice that when human resources are considered assets from an accounting and finance point of view, these critical assets then are viewed differently in the longer term, similar to product life cycles.

Here follows a brief description of the components of the model.

Acquisition efforts are not just recruiting efforts. When a human asset is acquired, the organization insures through proper planning that the human asset has a defined life cycle within the organization.

Then activities are put in place through on-boarding efforts to insure that the human asset is optimally motivated for peak performance through effective reward programs (both intrinsic and extrinsic).

Next activities are put into place to insure the human asset is adequately maintained through benefit programs to provide for the human asset’s life risk incidence needs, such as illness, disability, safety, and retirement.

Then the asset is developed through lifelong learning and development activities to achieve peak performance throughout the asset’s life cycle.

Another changed perspective in this model is the concept of summarily removing human resources (by way layoffs and terminations) for short-term financial gain. In this life cycle model (which takes the asset life cycle perspective), human resources are not easily disposed off, but are assigned to other appropriate best uses with adequate deployment efforts, which includes retraining and internal placement. This is similar to a hard asset retooling effort. Such a view of things, some postulate, will save organizations money over the long haul. Part II of this book revisits this point.

All of these life cycle phases of the human capital asset are supported in the HR department by certain core activities: an adequate job and skills database, a valid performance management system, an effective human resource information system, and a system of measurements with appropriate human resource analytics.