A Google search on the word “leadership” produces 464,000,000 results, but a search on “followership” results in 1,780,000 results, over 260 times fewer. Yet, both leadership and followership are required for organizations and projects to succeed. We expect followers to naturally know how to follow, but I don’t believe this is the case. Effective leaders set expectations of behavior and performance for their followers. Let’s begin our examination of followership by defining what a follower is and exploring the follower mindset.

You have probably seen different definitions of the word “follower.” The simple definition of a follower is someone who has chosen a leader. This means the follower has accepted and supports the leader’s vision and direction and will execute the plans that the leader creates. Leaders and followers have a symbiotic relationship. A leader cannot be effective without followers, and followers cannot succeed on their projects without effective leadership.

Ira Chaleff writes in The Courageous Follower, “Follower is not synonymous with subordinate. A subordinate reports to an individual of higher rank and may in practice be a supporter, an antagonist, or indifferent. A follower shares a common purpose with the leader, believes in what the organization is trying to accomplish, wants both the leader and the organization to succeed, and works energetically to this end” (Chaleff, 2009).

Have you ever worked with someone who is antagonistic or indifferent toward project goals, someone who only does the minimum amount of work to get by? Workers seek to perform tasks as documented in their position descriptions, objectives, or contracts. Followers are not limited to these written instructions. Not only do they accomplish the written instructions, but they also go beyond expectations to implement a project’s vision. Their individual goals intersect with project goals. They seek to satisfy not only the written requirements but also the intent of the leader. They use their initiative to satisfy the spirit of project requirements.

In the IT industry, you can expect your team members to challenge your leadership. IT workers are generally not conscientious about dotting every i and crossing every t, as discussed in Chapter 2. Researchers have concluded that failure on IT projects is generally the result of neglect of the behavioral and social factors—influenced by management, the organization, and the culture—rather than the technology itself (Th ite, 1999). Effective leaders influence behavioral and social factors through activities such as rewards, reprimands, training, and conflict resolution. Effective leaders connect with team members, motivating them by providing feedback and encouragement. Both IT geek project leaders and team members are responsible for paying attention to behavioral and social factors, for becoming more conscientious and building solid team member relationships, and for practicing effective followership rather than acting as mere workers—all in order to achieve success on IT projects.

Unfortunately, you will encounter some people on your team with the worker mindset instead of the follower mindset. They should be followers, but their mentality is that of a worker who shows up for work, does enough to meet minimum requirements, and then goes home. They do not respond to the effective leader’s high performance and ethical standards. They do not take initiative for tasks or take ownership of outcomes. They negatively impact team morale and productivity. They are not loyal, either to the project leader or to the team. I have had to address IT workers who are antagonistic or indifferent through reprimands, coaching, and external motivation, but my inner circle—those who I relied on to get the job done—were the followers. Followers are internally motivated—they are believers in the project vision; the others are not.

It is a leader’s responsibility to make sure followers understand the vision of a project. It is a leader’s responsibility to inspire followers to have the self-confidence needed to take initiative when it is required, making sure followers understand project requirements and goals to ensure that any initiative a follower takes is in line with these requirements and goals. But most importantly, it is a leader’s responsibility to make sure every team member is a follower and not just a worker. Your role is to challenge team members to set and maintain high standards of performance, empowering and encouraging them to achieve these levels. Through your dialogue with your team, through your actions and demeanor, your team members need to understand that you expect them to be followers rather than mere workers.

It is in your best interest to recruit team members who have a follower’s mindset rather than team members who have a worker’s mindset. In some organizations, it is very difficult to replace employees if it turns out they are not a good fit for the team. This means you need to develop skills for identifying, attracting, and cultivating talent. As a leader, you also need the courage to make the difficult decision to “release the worker to industry” if he or she is not willing and able to help you achieve the project vision.

This chapter will help you distinguish followers from workers. We will first take a look at the “Everything is Spinning” use case. Then, we will take a closer look at Effective Followership. Next, we will discuss the relationship between The Leader and the Effective Follower. On every project, there will be conflict, and we will next explore The Leader, the Followers, and Conflict. From here, we will explore Great Groups, then take a quick look at a technique I call Reverse Micromanagement, followed by concluding thoughts. At the end of this chapter, you will find a Followership Assessment that will help you examine your team and that can spark ideas on how to improve your team’s followership ability.

5.2 Use Case: Everything Is Spinning

“Two final agenda items and we can get out of this conference room and get back to real work,” said Terry at the weekly staff meeting, standing at the head of the table. “First, congratulations to Mark for developing an innovative solution for the authentication issue. That problem could have set us back for weeks.”

“Thank you,” said Mark, sitting with his fingers interlocked and his elbows on the table. “It was really no trouble at all,” he continued, looking at the table, not at Terry.

“Second,” Terry continued, “I almost forgot—everyone please welcome Tony, a new systems architect on Mark’s team. Tony, we are all looking forward to working with you.”

“Thank you,” said Tony, waving at the other staff members. “I am excited to be here!”

“Have a great Monday!” Terry exclaims, ending the meeting.

Jack approached Tony in the corridor after the staff meeting. “I’m Jack,” he said, “and I’m one of the engineers on Mark’s team.” “Nice to meet you,” Tony replied as they shook hands.

“I have to go to an orientation meeting at headquarters,” Tony said, “but can we get together later? Mark said you designed the cloud infrastructure and I’d like to talk to you about it.”

“No problem, stop by my cube in the morning,” Jack replied.

Then, Jack looked left, then right, then leaned toward Tony and lowered his voice, saying, “A word of caution about Mark. He will claim your work as his own. If you have a good idea, reveal it to Terry after you’ve worked it out and documented it. You know the solution to the authentication problem Terry credited to Mark? I discovered the problem and worked with the vendor to develop the fix. All Mark did was submit the change request—the change request that I wrote—and he put his name on it. Watch your back.”

“Wow—OK,” replied Tony, leaning back a little, brow furrowed, folding his arms in front of him. “I have to go,” he said. “See you in the morning,” replied Jack.

The next day, Mark called Tony into his office. As Tony entered, he noticed several framed training certificates, certifications, and diplomas proudly displayed on Mark’s walls. “Why would anyone still display an MCSE 4.0 certification?” Tony thought. Mark’s office was pristine, and he had a big, brown, plush leather chair that seemed out of place behind his rather ordinary office desk. Mark sat in his leather chair, and Tony sat in a chair in front of Mark’s desk. “Why is this chair so low?” Tony thought.

“I don’t want you talking to Terry,” Mark said. “He has no idea what he’s doing. He doesn’t have a clue.”

“What do you mean?” Tony asked.

“The requirements are all wrong, and he won’t push the customer to change them. If I were running this program, I’d tell the customer that they don’t understand what they’re asking for and restart the requirements gathering process,” Mark said.

“You’d start from scratch?” Tony asked incredulously. “Haven’t we deployed Version 1?”

“The customer can afford to start over. They have deep pockets. They just need to be convinced. I’m going to get these requirements changed. Our revenue will double. I know what’s best for them, and for the company, trust me. But I don’t want you talking to Terry. Do you understand?” Mark asked, leaning forward, looking sternly at Tony.

“Yes sir,” Tony replied.

On Wednesday morning, Tony arrived a few minutes early. As he walked by Mark’s office to his cube, he notices Mark’s lights were on, but that the room had been cleaned out. No certificates or diplomas on the walls, large leather chair gone. “That’s odd,” Tony thought.

At his cube, Tony saw a sticky note on his monitor from Terry that said “Come see me.” Tony headed to Terry’s office, arriving at the same time as Jack.

“Good, you’re both here early,” Terry says. “C’mon in, have a seat.”

Tony and Jack sat at the table, and Terry moved from behind his desk to a chair at the table. “Good morning,” Tony said. “What’s going on?” Jack asked.

“Well guys,” Terry began, “Mark is no longer employed here.”

“What happened?” Jack asked.

“You may not know this,” Terry said, “but Mark’s wife is a sales manager at CloudMatics. He’s been lobbying to change the cloud services solution to CloudMatics Hosting Services instead of Nebula Services. Last night, he got into an altercation about this with Dr. Tanner, the deputy CIO and program sponsor, and he called Tanner an idiot. Tanner called me and directed me to remove Mark from the contract immediately.”

“He called the program sponsor an idiot?” asked Jack, incredulous.

“Wow,” said Tony. “What a first week. Everything is spinning around me.”

“I’ll be overseeing your work until we find a new project manager,” said Terry. “This time, we will be more thorough in our recruiting effort and find the right fit. The PM not only needs to be a leader, he or she needs to be a team player and support the project vision and not go behind my back.”

After a pause, Jack leaned back, looked at Terry, and said, “So can I get the big brown chair, or not?”

Terry needed Mark to support the direction of the project whether he agreed with it or not, but Mark had other ideas. Followers need defined and shared goals that lead to the fulfillment of the organization’s vision. Warren Bennis wrote in “The Secret to Great Groups,” appearing in Leader to Leader in 1997, “All great teams—and all great organizations—are built around a shared dream or motivating purpose” (Bennis, 1997). Dr. Richard Steers and Dr. Lyman Porter, pioneers in goal psychology, describe four major goal functions: goals provide direction, define criteria for evaluation, lend legitimacy, and prescribe organizational structure (Porter and Steers, 1974). As an IT leader, defining and clarifying these goal functions, creating a unifying purpose, is a major element of our position.

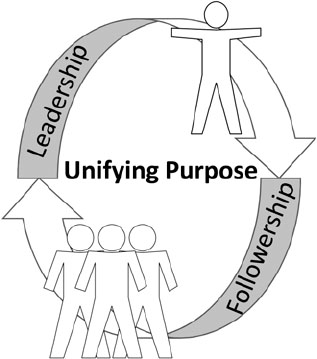

Followers are looking for leaders and causes they consider worthy of their commitment. As illustrated in Figure 5-1, they need a unifying purpose, vision, goal, or cause that can motivate them to contribute their best (Collins, 2013).

Followers need to feel that the efforts they put forth are not in vain, that they are making a difference. Contributing in this manner enhances their self-esteem and gives them a reason to get up in the morning. We spend more time when we are awake on our jobs than we do at home, with our loved ones. We want to spend this time in a meaningful way, a way that makes a difference, a way that is important.

Figure 5-1 Unifying purpose.

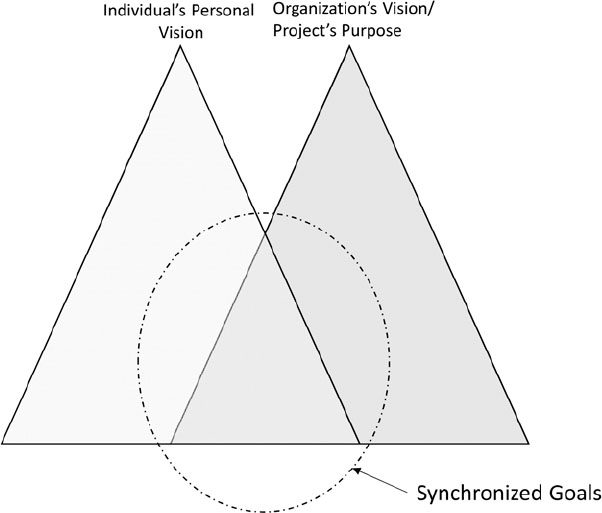

Your challenge is to develop situations, when possible, in which the organization’s goals and your follower’s goals are in sync, as depicted in Figure 5-2.

Followers need to perform tasks that the leader cares about. The follower may do many things well, but if he or she does not accomplish what the leader needs accomplished in a way that satisfies the organization or project vision, the follower is not effective. As a 19-year-old working on my first technical job, I received this advice: solve your boss’s problems first. Over 30 years later, I still apply this principle every workday.

Many followers have a burning desire to devote themselves to a common cause, to make a contribution, to be part of something bigger than themselves. Leaders are challenged to help these followers define this cause, to craft and project a vision that includes their likeness, to help them imagine themselves in action making the vision become a reality.

Followers who operate in this manner achieve their self-esteem and perhaps their self-actualization goals through followership, thereby satisfying their own inner motivation.

Your followers need opportunities to find success and happiness in their careers. They are looking for leaders who can provide opportunities to advance, make more money, and achieve their personal goals. They want to feel secure in their jobs so that they can pay their rent, purchase homes and cars, send their children to college, save for retirement, and take care of aging parents. Their reasons for being on your team are personal, and they take their experience on your team and with your leadership personally.

Figure 5-2 Individual and organizational goals.

Followers want to feel they are in control of their tasks and positions. They want you to provide them the authority to make decisions about how to perform their assigned tasks, and they want you to support their decisions. They look to their leaders to let them know why their tasks are important, and how their tasks fit into the overall vision and purpose of the organization; your response concerning the purpose of their tasks serves as a source of motivation. As their ability to pursue their own ideas during execution increases, so does their influence, and so does their job satisfaction. Once you empower your followers to make decisions on how to pursue project tasks, you should expect them to keep their commitments and to follow through on their decisions.

Your followers will react to your challenges; they need you to challenge them. Edwin Locke was professor of business and psychology at the University of Maryland in 1968. He found that goals cause behavior. His research found that hard goals produce a higher level of performance and that specific hard goals produce higher levels of performance than “make your best effort” goals (Maley and Varner, 1994). Give your team members specific challenges; set high standards and hold them accountable.

Your team members will be more effective and productive when you involve them in setting these high standards. Followers need to participate in goal setting in order to feel commitment and to have a sense of personal involvement—ownership—for the required tasks. Researchers have found that follower goal acceptance is a critical factor for follower performance (Porter and Steers, 1974). Followers need to feel that there is a high likelihood that they will be rewarded for attainment of a goal and must assign value to the reward in order to feel motivated to perform well. Goal acceptance and value assignment differ from person to person, so you need to know your team members as individuals to understand how to motivate them.

Like Terry and Mark, leadership and followership are ineffective if leaders and their team members are out of sync. Let’s explore the relationship between the leader and effective followers.

5.4 The Leader and Effective Followers

Effective followers are not afraid to take responsibility, and you should not be afraid to give it to them. The more leaders empower their followers to act, take responsibility, and act as leaders in their own right, the greater the benefit to the organization. On one occasion, I recognized that a team lead had developed a system to recognize his top desktop support performers. He called it the “100 Plus Club,” which pointed out team members who had solved 100 problems in a month while at the same time remaining compliant with service level agreements. This was exactly the type of motivation and recognition system needed for all teams in his division. The team lead’s supervisor submitted him for our quarterly leadership award, and he won. He certainly got my vote!

I eventually promoted him to regional manager and challenged him to implement the 100 Plus Club concept for each team in his region. I made it known that I wanted the 100 Plus initiative implemented across the program. I was thrilled when I was notified that each team in his region had recognized 100 Plus Club members, but I was ecstatic when a regional manager from another region in the program did the same thing shortly afterwards! By giving the inventor of the 100 Plus Club more responsibility and empowering him to act, we transformed the organization. We motivated the technicians, stimulating their internal motivation, resulting in better service to the end user customer and achievement of our program goals.

In this section, we discuss what motivates followers. Your team members need your encouragement. When requirements are not clear, they need you to provide clarity. Many followers want to be associated with good leaders—leaders with the courage to protect their team members and the heart to care for and support them and show appreciation. Team members who feel appreciated take initiatives that lead to project success. These effective team members create and adhere to their own high standards. Reward these followers with training and development opportunities and give them feedback on their efforts, and you will find that their morale will increase and your organization will be more successful.

A leader’s job includes encouraging team members, especially during discouraging situations. As a leader, your self-talk needs to include language that provides self-encouragement, such as “I am not easily discouraged.” If you are discouraged, you will find it difficult to encourage others (Collins, 2013). Many followers are in search of a role model, someone they can emulate so that they can enjoy a long, successful career. They want someone they can imitate until they can find their own way. Such team members need your support and encouragement, so you need to stay positive as best you can.

Leaders need to delegate to followers, and followers need to feel empowered. To empower a follower, the leader delegates authority, giving the follower the right to take action and make decisions on the leader’s behalf. Th is empowerment is a source of motivation for the follower, because the follower knows his or her actions directly contribute to the attainment of the vision of the organization or project. The follower needs to feel not only responsible, but also in control. The follower does not want to be responsible for any situation he or she cannot control, as this situation leads to failure.

However, IT leaders can only effectively empower experienced IT professionals. Researchers have found that IT leaders need to employ a leadership style that is contingent upon the professional maturity of their team members and the ambiguity of the task (Faraj and Sambamurthy, 2006). When the team has a high level of expertise and when there is a high level of task uncertainty, empowering leadership is more effective. Empowering leaders encourage active participation from team members, placing a premium on their involvement in the project. When the team has a low level of expertise and when there is low task uncertainty, directive leadership is more effective. Directive leaders are not looking for initiative from the team members. Instead, directive leaders provide the expertise, guidance, and control needed to meet project objectives. Your challenge as an IT leader is to recognize when to employ empowering leadership and when to employ directive leadership. Your team and your organization will be more successful when you find opportunities to grow your less experienced team members so that you can empower them instead of engaging in a directive leadership style.

Followers may have a desire to associate with leaders who increase their own personal credibility. If the leader is perceived to be great, if he or she has an excellent reputation in the IT industry, for example, then the followers’ perceived stock is higher because of their association with this leader. Some of the “halo effect” of the leader is transmitted to the follower. Followers want leaders they can learn from. They want to become better, more capable people because of their association with the leader. They want to be part of something great, and they want to follow a leader who is pursuing something great. No one wants a “dead-end” job or a “dead-end” career. It is the leader’s responsibility to provide meaning to the follower’s position.

Followers do not want to work for people they consider lesser than themselves. They generally don’t want to be involved in any unethical activities. They want leaders who will help them stay on the straight and narrow and avoid situations that can affect their reputation, bank account, career, or freedom (Collins, 2013). Instead of behaving like Mark, they need you, their leader, to uphold the highest ethical standards.

Followers need and appreciate leaders who motivate them, that push them to perform more and better than they think they can perform. I once had an impromptu meeting with our portal administrator. She was gathering requirements for a portal redesign, and she was having trouble reconciling the various requirements she gathered from different users. She was going down the path of creating meta-data requirements for users to follow when submitting documents so that others would quickly be able to find what the users posted.

I told her that my opinion was that her approach was academically correct, but in our environment, users posted documents on the portal to serve the needs of their own team. Users in our organization did not have a collaborative mindset, I told her, and getting them to follow meta-data rules would be very difficult. I recommended that she analyze portal search logs to find out what users were trying to find and incorporate that data into her solution. I also challenged her to define the benefits of collaboration and how the portal enables attainment of those benefits, then to work with our trainer to educate the staff on how our portal could help them realize those benefits in their everyday work. She appreciated the challenge and was motivated to improve the organization’s ability to collaborate, which would be a tremendous accomplishment for her and benefit for the agency. Leaders need followers to invest their time and creative energy in worthy tasks, and this portal administrator was willing to do just that.

Allowing followers to use their own initiative to make positive changes is critical to realizing innovative solutions to problems. Good leaders allow and encourage their followers to do more than expected, to take risks that will lead to novel, ground-breaking solutions. Good followers will test the limits of their authority, taking risks that will move the project or organization forward. Not all of their initiatives will lead to successful outcomes.

Figure 5-3 Team productivity and morale.

As a leader, provide your team members enough space to try, fail, and try again until success is reached. This is not always possible in every environment because of budget, schedule, and political constraints. Your challenge is to obtain space within the project environment for team members to take creative risks without penalty, risks that enable growth, recognizing that these initiative and innovation risks are necessary for positive changes that exceed customer expectations.

Figure 5-3 depicts the relationship between team productivity and morale. Leaders should empower and encourage followers to develop their own high standards of performance. The higher the group standard, the greater the quantity and quality of the group’s work. Researchers have found that team members who reported high coworker standards also reported high levels of pride, cooperation, and teamwork (Maley and Varner, 1994). These team members felt recognized for their performance and were motivated to make their best contributions to their project and organization. Lower expectations of performance had the opposite effect. High leadership expectations were reduced significantly in the presence of “peer pressure” for lower standards.

Followers who establish and achieve high standards are preparing themselves to become leaders. Their leaders need to recognize and groom followers who show leadership potential and encourage them to take on more responsibility. In the IT industry, in which many team members are prone to introverted communication styles and rebellious behavior, team members who overcome these tendencies and demonstrate the ability to set a positive example for their peers should be encouraged to lead. They should be given the proper training and the opportunity to experiment as a leader, to build positive leadership schemas, and to make mistakes and learn from them.

Followers need leaders to invest in their training. This demonstrates that the leader is concerned about helping the follower reach his or her professional goals. Increasing knowledge increases self-esteem, resulting in increased follower commitment to the leader and to the organization. This training arms team members with the knowledge and skills needed to take initiatives and mitigate risks.

At the same time, followers have the responsibility to identify their own deficiencies, comparing the tasks that they are assigned to perform with their own skills and abilities, and then to find training solutions to bridge that gap. Th is directly impacts the follower’s short-term success on the project and long-term success for his or her career.

The best performers on any team are those who practice self-leadership in order to be the best followers they can be. They treat their leaders as if they were customers, taking the initiative to understand the leader’s needs and then taking actions to exceed those expectations. They are internally motivated to perform in this manner. They do not need to be enticed by external rewards or coerced by potential punishment in order to perform at a high level. They perform well by habit and instinct, not because they have to but because they want to.

Researchers have found that team member morale is directly related to feedback from their leaders (Maley and Varner, 1994). Committed team members want to hear from you on a frequent basis. This consistent feedback increases morale, and the more feedback, the higher the morale. Your team members want your leadership assistance when needed, and your praise and recognition when they feel they deserve it. They want constructive negative feedback, not a “chewing out,” in order to be held accountable. Feedback on performance is the greatest motivator for team members. Leaders who provide this type of feedback produce productive, satisfied, and motivated team members.

5.4.2 Leaders Should Do What Only They Can Do

If you are a leader who has motivated followers, you are in a powerful position. If you have motivated, effective followers, they deserve a leader who will empower them. They need you to represent their ideas and initiatives in forums that you can access but they cannot. Leaders who support their followers in this manner deserve to be appreciated. In this section, we explore these ideas.

Great leaders typically desire to surround themselves with great people. They need people who can provide them with the support and advice they need to achieve the vision of their organization. They need people who can successfully execute the plans that they develop. Leaders need followers who are skilled in doing the tasks that the leader does not need to do, allowing the leader to empower his or her followers and focus on tasks that only the leader can do for the team.

While followers may want this empowerment from a leader, they may not know what the leader has to do to enable such a situation. The leader has to do the things only he or she can do for the project or organization, such as represent the team to senior leaders and to customers, fight to obtain resources, build goodwill with stakeholders, and promote and support team members’ ideas and initiatives to stakeholders and board members.

Leaders spend time engaging with stakeholders to build support for team initiatives—including those spearheaded by followers—prior to acceptance and execution. If you are doing tasks that a team member could do, you are neglecting your leadership duties.

No one else speaks for the team. No one else integrates the work of each team member. No one else represents the team to senior management. No one else establishes the vision—the unifying purpose that brings everyone together and makes them feel like they are contributing to something important. While leaders focus on these important tasks that no one else is responsible for performing, team members can focus on their specialties with the assurance that the leader is bringing everything together (Collins, 2013).

How do you feel when a team member shows appreciation for your leadership efforts? I personally find this gratifying. Like followers, leaders also need encouragement. Leaders appreciate positive feedback from their followers. They want to know that their initiatives are making a difference. They want to know that their followers’ lives are improved as a result of being part of the team. Good leaders make a sincere effort to take care of their followers, and they like to know those efforts are appreciated (Collins, 2013),

Regardless of how strong and mature your team is, there will be conflict, and your team members will look to you to resolve this conflict. In the next section, we discuss conflict management on project teams.

5.5 The Leader, the Followers, and Conflict

Followers don’t always agree with their leader’s direction and decisions. In such cases, they need the leader to allow them to express their perspective on the situation and to seriously consider their viewpoints. After their followers have been heard, leaders need them to avoid being discouraged, accept the final decision, and support the outcome. Disagreements need to be kept confidential so as to not give the appearance of disunity, which is a de-motivator. Followers lose confidence in the organization when they are exposed to strife. Conflicts can be misinterpreted and the source of uncertainty and rumors, but unity reassures followers that the organization is headed toward success. Unity builds momentum through motivation and creates positive feelings that lead to positive outcomes.

Leaders need followers who are willing to be strong critics of their plans and decisions (Collins, 2013). Leaders need these “devil’s advocates” to point out their blind spots. These healthy conflicts lead to better decisions and approaches to solutions. Leaders need the ground truth. They need followers who are courageous enough to deliver bad news to their leaders when these leaders are considering options for the way forward. In order to obtain the feedback they need, leaders should cultivate an environment in which followers feel safe enough to provide negative feedback. Followers don’t want to be considered complainers, and they don’t want their negative feedback to lead to missed promotions and reduced raises.

If the leader does his or her part, and the followers do theirs, the team will be strong and capable.

Followers typically support good leadership and resist bad leadership. Followers who do not support their leaders or their vision may circumvent them and join with other followers, causing conflicts (Kellerman, 2008). I have seen this happen. Red flags go up on programs when committed team members request to be moved to another team. When this happens, I look for the tacit back story, the illusive ground truth about what is really happening on the team. As a leader, I often don’t hear this story until it is too late make changes, to introduce a new narrative. I listen for it, but I don’t always hear it.

Leaders and followers should never compete. This unnecessary competition is another source of conflict. Followers should not compete with their leaders, but should instead support them, accomplishing the tasks required to achieve the leader’s vision. Good leaders reward followers who embrace their leadership, recognizing that followers who commit themselves to contributing to the realization of the vision do so voluntarily. Good leaders don’t take such voluntary commitment for granted.

Years ago, I experienced a leadership change while working for a small company. I found myself under the supervision of a new boss and a new boss’s boss. If you have never experienced anything like that before, I can tell you that it is very stressful. As a PM, I did not know if I would be replaced by someone that my boss or my boss’s boss preferred for my position. During such volatile times, changes in key personnel are not unusual, and neither is the stress that stems from the uncertainty. I was challenged to first keep calm myself so that I could keep my staff calm. Yes, times were uncertain, but for most of us, there was no reason to panic. If we panicked, we would not be able to think clearly enough to navigate through the change.

Conscientious new leaders build relationships with their subordinates in order to be successful. Every leader has his or her own way of building these relationships. In my case, my boss’s boss, let’s call her Sandy, decided that the company should fire one of my senior managers because of her perceived leadership deficiencies. This leader, let’s call her Jan, was effective, but not a rock star. Jan delivered, but not in a way that inspired her team members. Jan struggled at times, but not in an egregious manner, not in a manner that, in my opinion, should have put her on the chopping block. But Jan had reason to panic.

I did not agree with firing Jan, but I was unable to convince Sandy that Jan should stay. I did not know Sandy, and I felt as though she was testing me—perhaps this was her way of testing my obedience to her. I felt as though my job was on the line if I did not submit to Sandy’s demand. I held my nose and carried out my assignment. Even as I write this, my stomach turns.

During this situation, I developed a cynical definition of loyalty: loyalty means you are willing to carry out your leadership’s vendettas as if they were your own. Your leadership’s resentment becomes your own resentment; you develop a need for vengeance that is married to your leader’s need for vengeance, a need that is satisfied only when your leadership’s vengeance is satisfied. I felt like I’d been inducted into the mob.

I had to prioritize my fears. I was afraid of losing my job, of being unable to take care of my family, pay my mortgage, and put food on the table. I was more afraid of not being able to fill my safety and physiological needs than my self-esteem needs.

You can learn something in almost any situation, and I learned how hard being a follower can be. I would never put any follower in such a position, and you should not either.

Followers at all levels face tough decisions that impact their character and reputation. The follower’s values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations influence those decisions. Followers don’t want to be put in positions in which they are asked to lie or break the rules on behalf of the leader or the organization. While working as a senior manager in a government contracting firm years ago, I was informed of a situation in which our contractors were directed to purchase items such as cell phones for the government customer and then to submit expense reports for those items, expense reports that the government customer approved. This action was done in such a way that we could not determine if the expenses were justified or not. Everything looked good on paper. But the employees knew. The government customer, in a leadership position, put the contractors—their followers—in a precarious position in which they had to make a choice: follow the direction of the government customer or risk being removed from the contract and losing their jobs. We experienced turnover, understandably. The contract ended and we did not win the renewal. While we missed having the business, I did not miss having to interact with an unethical customer.

If followers do not want to follow a leader, if they do not buy into the leader’s vision, they will not be fulfilled, and they should follow someone else.

Followers working together as a team have a shared purpose—a purpose that the leader defines. The major influences on a team are team goals, team atmosphere, team communications, and team maturity.

Leaders must effectively communicate their goals to their team in order for the team to be productive. The team needs the ability to measure its progress toward reaching the defined goals.

Followers react to each other in accordance with their perception of the reaction of the rest of the team. This team atmosphere governs whether or not team members feel free to contribute to team activities that lead to attainment of team goals. The more freedom they have to participate in a democratic and inclusive manner, the higher the team motivation and morale are for both leaders and followers.

IT leaders need the courage to overcome any introverted tendencies and to find the assertiveness necessary to communicate. IT followers face the same issues. Leaders need followers to openly express themselves so that the leader has the information he or she needs to achieve the desired project outcome.

Followers need to feel they are receiving the information they need to perform as contributing members of the team. Leaders need to engage in face-toface dialogue with followers whenever possible in order to facilitate authentic communications and to foster commitment for the individual. Followers need to see the body language of the leader. They need to connect both verbally and nonverbally so that they understand both the leader’s stated intention and the spirit of his or her intention. They need the freedom to express to their leader how they feel, so that when the leader asks why the team member feels the way he or she feels, the leader will discover ground truth. They need to have this communication with others on the team as well, building relationships and trust, comparing and contrasting each other’s values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations, as discussed in Chapter 2. The stronger the communications network among the team members, the more productive the team and the greater the likelihood that the leader can obtain the vital information he or she needs when needed. Table 5-1 lists follower behaviors that gain the leader’s trust.

Table 5-1 Gaining the Leader’s Trust

Followers Gain Their Leader’s Trust By: |

• Demonstrating complete loyalty and respect for the leader • Demonstrating professionalism in performance and emotional maturity in their approach to satisfying project and organization requirements • Demonstrating support for the leader when publicly representing the project and the organization • Demonstrating commitment to delivering on the leader’s final decision regardless of any disagreements experienced during the decision-making process • Demonstrating professional accountability for themselves, their growth, and their behavior • Demonstrating the same concern and care for the leader as a person as the follower expects from the leader |

Data derived from Maley and Varner, 1994. Leadership: The Leader and the Group. Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press.

Followers who exhibit these qualities are worthy of their leader’s trust. Leaders can delegate tasks to these followers, empowering them with the authority to carry out assignments on the leader’s behalf.

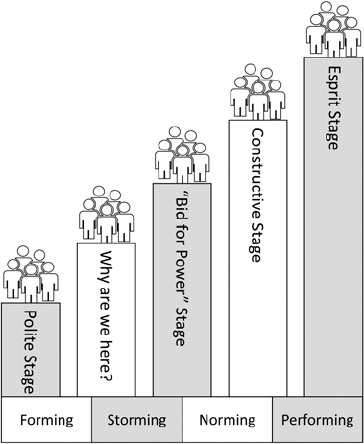

Followers working in teams or groups relate to each other through increasing levels of maturity. Figure 5-4 depicts two models of group behavior: Cog’s Ladder (Maley and Varner, 1994) and the Tuckman Model (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977).

Cog’s Ladder

The Cog’s Ladder Model has five steps: the Polite Stage, the Why are we here? Stage, the “Bid for Power” Stage, the Constructive Stage, and the Esprit Stage.

Figure 5-4 Cog's Ladder and the Tuckman Model.

1. In the first step, the Polite Stage, group members get acquainted, share values, participate in social interaction, and establish the group structure.

2. At the Why are we here? Stage, group members define and understand the objectives and goals of the group. To reach this stage, members risk the possibility of conflict and must deal with threatening topics.

3. The next step is the “Bid for Power” Stage, in which group members attempt to influence one another’s ideas, values, and opinions. In this stage, members risk personal attacks from other members. Some members may be required to submit to a purpose they disagree with.

4. In the fourth step, the Constructive Stage, the team begins to take action. They become open-minded, engage in active listening, and respect one another’s rights to different values and opinions. Some members may be required to cease defending their own views and accept the possibility that they may be wrong.

5. The last step is the Esprit Stage. Here, the group unifies and experiences mutual acceptance, high cohesiveness, and high spirits. Members have self-trust and trust other members.

The Bruce Tuckman Model

The Bruce Tuckman small group development model is based on his analysis of 55 articles on the stages of small group development. This model describes how group interactions change over time (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). I have overlaid Cog’s Ladder with the first four stages of the Tuckman Model in Figure 5-4.

1. In the Forming Stage, team members meet and are oriented to project goals. They learn the project and individual roles (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). Team members need the opportunity to get acquainted. They need essential information about the content and context of the work expected, and they discover their individual values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations. During this stage, the leader defines and clarifies the team vision and the goals to achieve the desired outcomes (Biech, 2008).

2. In the Storming Stage, the team seeks to understand the requirements, define an approach, and find consensus through collaboration. They respond emotionally to the required tasks at hand, potentially experiencing conflict (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). In this stage, the team leader needs to assertively set parameters for the team. Team members need to listen attentively to all viewpoints and employ conflict management techniques such as mediation, negotiation, and arbitration if needed. During this stage, team members and team leaders explore alternative ways to view the problems they are facing (Biech, 2008).

3. Next, the team enters the Norming Stage. Here, the team members adjust to one another and experience an open exchange of relevant interpretations of task requirements (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). Here, the team leader is required to provide opportunities for all team members to be involved and to learn from and assist one another. The project leader needs to model and encourage supportive behavior, keeping communication lines open. The team members need positive and corrective task-related feedback during this stage. Also during this stage, the successful team leader adds humor and fun to the team working environment (Biech, 2008).

4. The last stage, as depicted in Figure 5-4, is the Performing Stage, in which the team develops solutions, producing results and solving problems (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). During this productive stage, team members need to be rewarded and recognized for their contributions to the project and the team’s well-being. Team members participate in group problem solving, in setting future goals, and in shared decision-making opportunities. Team leaders delegate tasks to team members in this stage that foster their professional development (Biech, 2008).

5. The Adjourning Stage is not depicted in Figure 5-4. This stage was added to the model after the first four. Here, the group disbands after the project has ended (Jensen and Tuckman, 1977). During the separation process, the team leader provides evaluations and performance feedback. Team relationships and project success are celebrated, with an emphasis on fun and recognition (Biech, 2008).

The team will traverse up and down Cog’s Ladder, back and forth through Tuckman’s Model, in a dynamic fashion as the team pursues its vision. Changes in requirements, leadership, and team members result in changes to the team’s maturity level. Conflict is inevitable and normal. It is through this conflict that team leaders and team members learn and grow. Conflict builds character and maturity. Through these Cog and Tuckman stages, as a leader, you are expected to facilitate conflict resolution. Do it in a way that encourages your team members to learn and grow, and your team and organization will be stronger. You can influence the success not only of your team as a whole, but also your team members in a very personal way.

Psychotherapist Joyce Marter provides 10 Tips for Resolving Conflict, which I have adapted for your use, below (Marter, 2013):

1. Allow your team members time to pause and get grounded between the time of the conflict and your attempt to resolve it. When tempers are high—when team members are experiencing the “amygdala hijack” in which their cognitive unconscious minds are on overdrive—is not the time for conflict resolution. Team members need to use their mindful, intellectual selves during the conflict resolution process.

2. Help team members see the issue from a higher perspective. Help them imagine that they are a third party that is looking at the issue for the first time. Help them emotionally detach from the situation and think about the real, underlying issue. Are they angry about the current situation, or are they venting concerning some pent-up resentment over a past issue? Help team members avoid arguing about minutiae and focus on the real issues. Help team members see the big picture—the overall vision. Remind them of the noble motives of the project and how their roles relate to those motives.

3. Pay attention to nonverbal communication, your own and that of your team members. Be aware that your facial expressions, hand gestures, and body language may send messages that could be misinterpreted. If you recognize nonverbal communication that could be misinterpreted, intervene immediately.

4. Set ground rules early concerning behaviors that are counterproductive to conflict resolution. Team members should not be permitted to physically or verbally abuse each other. They should avoid criticism and character attacks. They should avoid contemptuous behavior such as insults, eye rolling, stonewalling, and defensiveness.

5. Encourage team members to empathize with each other. Help them imagine themselves in the role of the other team members involved in the conflict, to imagine how it feels to face the challenges of being in their roles.

6. Encourage team members to take responsibility for themselves. Team members need to exercise honesty and integrity, owning up to their contributions to the conflict.

7. Encourage team members to be direct and assertive, not passive, aggressive, or passive-aggressive. If possible, communicate in person instead of over the phone. Avoid attempting to resolve conflicts through email, because this media is easily misunderstood and is often the very source of conflict.

8. Help team members to be active listeners by encouraging them to ask clarifying questions. Help them find common ground and “win-win” solutions.

9. As team lead, you can attempt to facilitate conflict resolution, but you cannot control how others will react. You can control your own behavior, so make sure your actions contribute to the resolution and do not make the conflict worse. Stay calm and help others stay calm. Apologize for any misinterpretations, setting a model for team members to emulate. Be fair in your judgments; do not show any favoritism.

10. Help team members to realize what they have learned through the experience of both the issue and the conflict resolution process. Encourage them to forgive and let go. Help the team members develop a positive path forward.

I used these guidelines to facilitate resolution of a conflict between one of my managers and one of his team members. The team member had become extremely upset because he perceived that the manager had disrespected him. He hastily resigned. The manager was upset with the team member because he felt he was insubordinate. I did not want to accept the team member’s resignation until I understood the issue. I did not want him to resign over a simple misunderstanding. During the conflict resolution process, the team member explained that as English was his second language, sometimes he misinterpreted what he heard. The team member did not understand the criticality of performing the task that the manager directed him to perform, so I asked him to imagine how he would feel if he were in the manager’s situation. He then understood the manager’s frustration with his actions. The team member had interpreted the manager’s direct manner of providing direction as “yelling” and felt disrespected. But he had never asked the manager why he reacted as he did, he just assumed the manager did not respect him as a person.

I asked the team member to take a pause the next time he felt the need to react emotionally with a team member or manager. Instead of reacting based on an emotional assumption, I encouraged him to take a break, calm down, and then ask the other person to clarify what he or she had said, then to react mind-fully and intellectually, instead of emotionally.

During the conflict resolution process, the team member frequently pointed his finger at the manager when trying to explain himself. I stopped the team member, looked at him and said, “You don’t realize what you just did, do you?” He stared at me blankly. I said, “When you pointed at him, I felt uncomfortable. I felt emotions build up inside of me when you pointed at him because your body language was offensive.” The manager said, “That’s right. I was getting angry because of your pointing.” The team member said to him, “I did not realize I was making you feel that way! Why didn’t you say something?” “Now you see my point,” I said. “You did not intend to offend him with your pointing, but you did. In the same way, he did not intend to disrespect you. The next time you feel disrespected, take a break, calm down, and then ask the other person to clarify what he said so that you do not misinterpret the situation.”

The team member decided not to resign, which was good for him because if he had not provided a two-week notice, we would not have been in a position to provide him with a positive referral for this next job. It was good for us because we did not have to recruit to find a replacement. The team member thanked me several times for intervening in this process. He said he had learned much from the experience, about himself and about the challenges of interpersonal communications.

Resolving conflicts faced during the team development process, traversing through the Cog and Tuckman Models, are one way of providing feedback to followers. Leaders also provide followers feedback through praise and reprimands. Followers need both of these in order to understand the behavior the leader expects in order to perform project tasks and to successfully interact with the team. Let’s take a look at the processes for providing praise and reprimands.

I find myself in situations in which I have to make choices concerning personnel discipline, personnel salaries and raises, and the impact on the program budget of bringing on new people. These decisions affect the performance as well the profitability and other financials of the program, and they affect the livelihood of the personnel involved. How I approach these decisions are a reflection of my character and impact my reputation.

Figure 5-5 Praise and reprimands.

Followers respect leaders who provide both praise and reprimands. Leaders should not recognize good performance and overlook poor performance, as this leads to a lack of team member accountability. Conversely, the leader should not overlook good performance and only pay attention to poor performance, as this leads to employee dissatisfaction and poor morale. Leaders who are disciplined in the application of both praise and reprimands set and reinforce standards of behavior, providing the team member the feedback needed to meet performance expectations and make positive contributions to the achievement of the team’s purpose. Figure 5-5 shows the steps required to effectively provide praise and reprimands (Mayer and Varner, 1994).

A leader should praise followers by:

• Immediately recognizing positive performance.

• Being specific with the follower about what he or she has done right and how it impacts the project vision.

• Expressing his or her good feelings about the follower’s good performance.

• Pausing to allow the follower to internalize how good it feels to receive praise—a feeling the follower will want to feel again—and how good the leader feels about the performance.

• Encouraging the follower to continue performing at a high level.

At the same time, a leader should reprimand followers by:

• Immediately addressing poor behavior.

• Being specific with the follower about what he or she did wrong.

• Expressing his or her feelings about the follower’s poor performance.

• Pausing to allow the follower to internalize how bad it feels to be reprimanded—a feeling the follower will want to avoid in the future—and how bad the leader feels about the poor performance.

• Expressing that he or she values the follower as a person, showing that the leader means no harm and that his or her only intention is to help the follower perform at a high level. The leader should shake the follower’s hand in order to express openness, warmth, and concern for the individual.

• Recognizing that the reprimand is over and holding no resentment toward the follower. Resentment is a poison that can destroy relationships between leaders and followers and that could lead to unnecessary vengeance.

Followers who are forced to perform tasks they do not really want to do—things they do not agree with—may harbor negative emotions such as resentment and guilt. When asked if they will perform the task they disagree with, they may reluctantly say “yes” because they fear the consequences of saying “no.” Good leaders don’t put followers in such positions. The resentment caused by such demands builds up within organizations over time and is poisonous. Nelson Mandela said, “Resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies.” Just as negative self-talk is poisonous to a person’s self-image, resentment, guilt, and other negative feelings lead to grumbling and murmuring—poisonous self-talk that can debilitate an organization’s morale and culture.

It is in the follower’s best interest to make an effort to discover any resentment the leader has toward him or her and take action to assuage it. This is done through honest dialogue and through building trust verified by performance. Followers who get the job done within expected timeframes and at expected levels of quality earn their leader’s trust.

Followers have the most at stake in the leader-follower relationship. It is easier for a leader to dismiss a follower, negatively impacting his or her career and livelihood, than for a follower to negatively impact the leader’s career. The leader simply has more power and access. At the same time, leaders will not succeed unless their followers perform. The trust relationship between leaders and followers is critical, as both parties have much to gain and to lose.

Followers want to choose the problems that they commit themselves to solving. They are motivated by the challenge of understanding the project situation, identifying problems that impede achievement of the desired state, and developing solutions for those problems (Collins, 2013).

While it is important for team members to feel committed to identifying problems, performing tasks, and developing solutions that lead to achieving the desired state, leaders need to help followers avoid territorialism. I have encountered situations in which followers felt like they needed to protect their turf. For example, on one occasion, a systems backup administrator that was very good at his job refused to document the backup procedures he developed. He felt that anyone who came after him should have to figure out the procedures just as he had had to do. His attitude made the team weak. If he were to win the lottery, or leave the project for whatever reason, the team would be challenged to continue backup operations. As the leader, I had to motivate him to complete the documentation and then have another administrator validate his documentation in order to mitigate the risk.

Encourage your team members to solve their boss’s problems first instead of exclusively performing the tasks they like. Solving your boss’s problems first requires proactive communication on the part of the follower. The follower needs to clearly understand the critical success factors for the job—the expected quality level, the schedule, the do’s and the don’ts. The follower should initiate conversations to determine these details, not wait for the busy leader to provide them. The leader may not know exactly what the follower needs to know, so the follower needs to ask questions until he or she sees the picture of what needs to be accomplished in the leader’s mind. Then the follower can develop a win-win approach that allows him or her to perform at a high level, including accomplishing tasks that interest the follower as well as meet the leader’s project requirements.

Leaders need followers to challenge ideas and approaches to problems. Leaders need “devil’s advocates” in order to vet ideas and to facilitate critical thinking. Leaders need to consider all sides of issues and to analyze multiple alternatives to solving problems. Without engaged followers, the leader’s ability to make critical decisions is diminished.

Followers have the responsibility to address conflict in order to improve situations for the sake of themselves, the team, and the team leader. Leaders should encourage and facilitate their followers’ internal motivation and self-leadership, enabling and empowering them to enhance their working life experience, giving them the freedom to influence the morale and feeling of goodwill within the team.

Warner Bennis wrote in The Secret to Great Groups, “How do you get talented, self-absorbed, often arrogant, incredibly bright people to work together?” (Bennis, 1997). He was not writing about IT geeks in particular, but his article is in line with what we experience in the IT industry.

Bennis continued, “As they say, ‘None of us is as smart as all of us.’ That’s good, because the problems we face are too complex to be solved by any one person or any one discipline. Our only chance is to bring people together from a variety of backgrounds and disciplines who can refract a problem through the prism of complementary minds allied in common purpose. I call such collections of talent Great Groups. The genius of Great Groups is that they get remarkable people—strong individual achievers—to work together to get results. But these groups serve a second and equally important function: they provide psychic support and personal fellowship. They help generate courage. Without a sounding board for outrageous ideas, without personal encouragement and perspective when we hit a roadblock, we’d all lose our way.”

Bennis provides 10 Characteristics of Great Groups in Table 5-2.

In your Great Group, if you find a skilled IT team member who can naturally communicate, is naturally conscientious, is naturally trustworthy, and delivers, you have found a natural IT leader in the making. Groom this diamond in the rough for leadership; bring him or her into your inner circle; challenge him or her with leadership opportunities; position him or her as someone other team members should emulate. Develop this leader so that he or she can one day lead a Great Group. As an IT geek leader, no one else on your team can do this but you.

Dr. Ginger Levin and Allen Green developed a Team Charter that is an excellent way to set followership guidelines for your team (Levin and Green, 2014). A team charter is an agreement on the standards of performance and behavior for project team members. It formalizes team members’ roles and responsibilities and provide guidelines for operations. IT geek project leaders can use the team charter to set expectations for team member interaction. Tailor your team charter to include the characteristics of great groups, genetically engineering greatness into the DNA of your team. Table 5-3 provides suggested elements for the contents of an IT Project Team Charter.

Table 5-2 10 Characteristics of Great Groups

10 Characteristics of Great Groups |

• “At the heart of every Great Group is a shared dream.” IT geek leaders are responsible for crafting and articulating this shared vision or purpose, and IT geek team members need to buy into it. • “They manage conflict by abandoning individual egos in the pursuit of the dream.” IT geek leaders need to work with their team members to find the intersection of personal goals with project and organizational goals. • “They are protected from the ‘suits.’” The IT geek project leader’s job is to be a firewall between the politics of senior leadership and daily project operations, giving team members the mental space to focus on achieving the project’s vision. • “They have a real or invented enemy.” A common enemy bands the team together, motivates them to work together to defeat an adversary. This adversary may be another IT company or another development or operations team within the company. • “They view themselves as winning underdogs.” I have encountered many IT geeks who are achievement oriented and that are looking to make a name for themselves within their companies. • “Members pay a personal price.” Committed IT professionals in both technical and leadership roles are often required to work long hours, weekends, and holidays. Self-leadership activities such as developing and maintaining a personal IT lab at home or performing independent research require a sacrifice of personal time. • “Great Groups make strong leaders.” Groups that produce great results spawn leaders, followers who become leaders in their own right. • “Great Groups are the product of meticulous recruiting.” A common mantra among IT leaders is “hire for attitude and train for skill.” A former boss of mine equated IT workers to athletes. “I can train a good athlete to play any sport,” he said. But if it turns out that the athlete does not have the talent you need, don’t try to work around the issue. Refine your recruiting process, and replace the poor talent with a better athlete. Your other, more talented team members will appreciate the opportunity to work with more talented teammates, and your team will be more productive in the long run. • “Great Groups are usually young.” Not young in age, but in spirit and energy. • “Real artists ship.” In the end, Great Groups produce tangible results. |

Data derived from Bennis (1997). “The Secrets of Great Groups.” Leader to Leader, 3(4).

Table 5-3 IT Project Team Charter

The IT Project Team Charter Contains: |

• Project purpose statement • Project scope and boundaries • Project deliverables and assigned responsibilities • Team member commitment statement • Program/project sponsor role • IT project leader role • Client role • End-user role • Team member performance objectives • Team member success measures • Conflict management process • Issue escalation process • Decision-making process |

Data derived from Levin, G. and Green, A. (2014). Implementing Program Management. [Kindle Version].

As an IT geek project leader, brief each team member on the project charter. Allow team members to ask clarifying questions and ensure that they understand the document even if they don’t agree with it. Don’t expect every team member to be receptive to the team charter. Require team members to sign an acknowledgment indicating that they have been briefed on the contents of the document, explaining that the acknowledgment does not signify agreement, only that they have been briefed. Explain to your team members that you expect the team to be great, and that the team charter is the roadmap for team greatness. Once you have done this, you can hold your team members accountable for meeting the standards you have established for your team and you have increased the likelihood that your IT project will be successful.

Nearly every experience provides a learning opportunity, even the experience of working under poor leadership. Poor leaders teach followers how not to behave. If the followers are paying attention, they will recognize poor leadership and remember their experiences when it’s their turn to lead, remember and behave differently, and thereby become better leaders.

In the IT industry, research has shown not only that more leadership is needed in order for projects to have a higher probability of success, but also that neglect of behavioral, social, and managerial factors attribute to project failure (Thite, 1999); so do not be surprised if you find yourself subordinate to someone who is a poor manager and leader. I have found myself in this situation more than once. I had a difficult time obtaining the leader’s trust, and as a result, he overly involved himself in the details of the project. Each time this happened, I am sure the leader had valid reasons for his actions: high pressure from his superiors, a history of previous failures on similar projects, political conflicts and disagreements at his level and above, dependence on the success of the project for the leader’s promotion or bonus—the list could go on.

Investopia.com provides a great definition of a micromanager: “A boss or manager who gives excessive supervision to employees. A micro manager, rather than telling an employee what task needs to be accomplished and by when, will watch the employee’s actions closely and provide rapid criticism if the manager thinks it’s necessary. Usually, the term has a negative connotation because an employee may feel that the micro manager is being condescending towards them [sic], due to a perceived lack of faith in the employee’s competency. A micro manager may also avoid the delegation process when assigning duties and exaggerate the importance of minor details to subordinates” (Micro Manager, n.d.). I find it interesting that the subject of their definition is “a boss or manager” and not “a leader.”

If you find yourself in a situation in which you are being micromanaged, my recommendation is that you employ something I call “reverse micromanagement.” I don’t mean to use this term in the pejorative sense. Reverse micro-management as used here concerns communication. As communication is the foundation of program and project management, reverse micromanagement means providing your manager information about your project on a frequent basis. It simply means providing information and updates and asking for direction at frequent intervals, say every hour (or less). You, as the follower, initiate the communication whether the boss asks for information or not.

Only you can judge whether it is politically and socially safe to deploy such a technique. In the best case, your boss (say, for this example, Stephen) may be very happy to receive the information. You may build trust with him, establishing a solid relationship. You may convince him by your actions that he can delegate tasks to you without worry, that he can empower you without fear. In this case, let him tell you when he is receiving too much information. In this best case, your investment of time and energy to over communicate has paid off.

In the worst case, Stephen may be irritated by the frequent information updates. Be very careful in this case, because there may be an underlying reason that he does not want to hear from you, something political or personal, perhaps some type of hidden resentment. In this case, have a frank conversation with your boss and tell him how you feel. In this case, you are hemmed in, and there may be little you can do other than escape from your involvement with your boss.

In either case, if you pay attention, you will learn from the situation. You will gain experience to draw from, to build schemas that will help you determine the type of leader you want to be. You will understand how your followers perceive your actions, how and why they may interpret your style as micromanagement. Use this experience to gain self-awareness. Use self-leadership to become a “macromanager,” someone who defines work in broad terms, builds trusting relationships with your followers, and then leaves them alone to do their work.

This chapter is about followership, which is another perspective on leadership. Now that you understand followership, you have an opportunity to be a successful IT geek project leader. You can do this by developing and encouraging your team members to be effective followers. You cannot neglect the behavioral and social factors of IT professionals—their tendency to be introverts who do not communicate well, their tendency to be somewhat rebellious against organization and project rules, norms, and values. Instead, clearly define the purpose of your project and capture it in a team charter. Identify and develop followers—team members that buy into the project’s purpose and that will rally behind you as you lead them to achieve the goals of your IT project. Reprimand behavior that does not support the project’s vision, and reward behavior that does. Empower and encourage mature performers who deliver so that less mature team members will want to emulate them. Be inclusive. Involve everyone in making project decisions when practical, even the most withdrawn members of your team. Earn your team’s trust, and create opportunities for your team members to earn yours. Success is within your reach—be the leader your team members—your followers—and your customers expect and need you to be!

In the next chapter, Personal Credibility, we discuss proactive principles that geek leaders personify to earn a solid reputation, professional influence, and respect not only from followers, but also from peers and senior leaders.

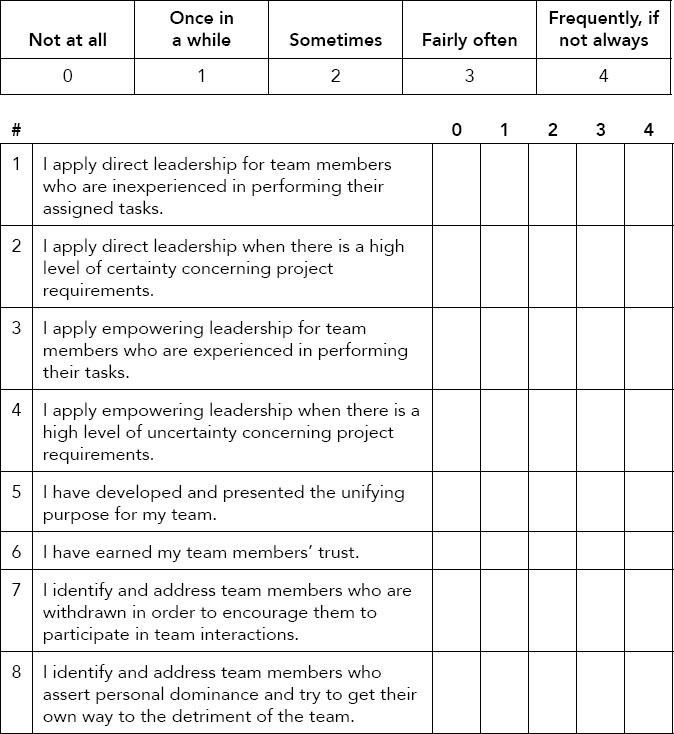

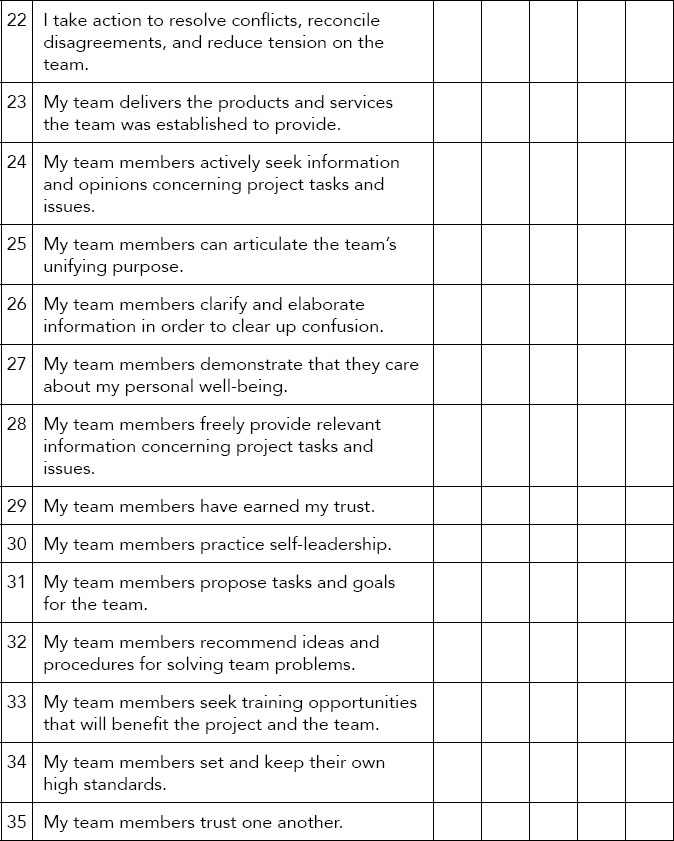

Followership Assessment

The assessment below can help you think about your leadership effectiveness and the followership effectiveness of your team. You can use the results of your assessment to develop an action plan to improve your team’s followership ability.

Use the following key for this assessment: