Taking a Look Under the Hood of the Interface

A Wide Range of Problems

As we have shown in the previous chapter, the interaction between sales and marketing leaves a lot to be desired in many companies. When sales and marketing fail to communicate effectively and work at cross-purposes, it not only leads to a dysfunctional interface but also results in inefficiencies and missed opportunities. In this chapter we take a closer look under the hood of the sales-marketing interface, to see what fails to make it run smoothly. What are the most common problems between sales and marketing? What causes these problems? What does this mean for a company’s business performance? And how does all this depend on the type of company?

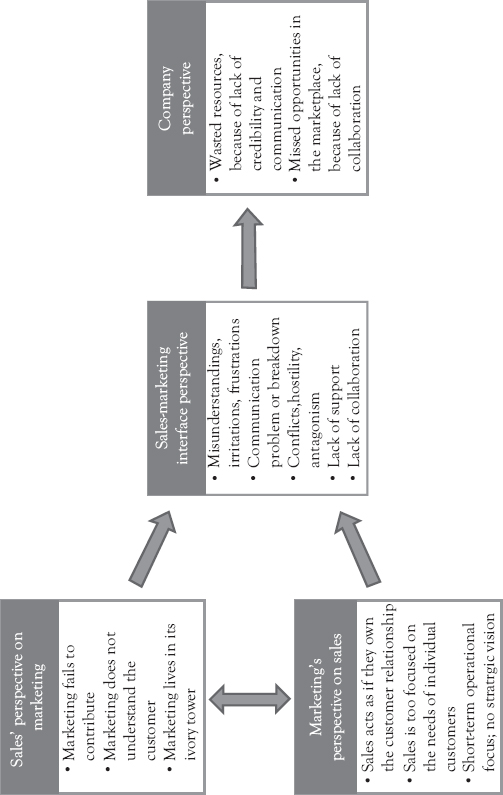

Companies with dysfunctional sales-marketing interfaces experience a host of different problems, which we classify as follows (Figure 3.1):

1.Problems from the perspective of sales.

2.Problems from the perspective of marketing.

3.Problems from the perspective of the sales-marketing interface.

4.Problems from the perspective of the company.

As we discuss these multiple perspectives on what may afflict sales-marketing interfaces, we draw upon our extensive research across multiple industries in different parts of the world. We blend our research findings in this chapter in the form of many interesting quotes from the sales and marketing managers we spoke with as a part of our multi-year research. These quotes bring to life many of the deeper level issues that sales and marketing personnel grapple with on a day-to-day basis.

Figure 3.1 Classification of sales-marketing interface problems

Problems from the Perspective of Sales

In any company with a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface, both parties are usually quick to blame each other. From the perspective of sales, a problematic interface is largely caused by marketing not doing what they are supposed to do. Salespeople see themselves as productive employees who have daily contact with real customers, and it is their job to get purchase orders from these customers. In addition, they spend time and effort to maintain and further develop relationships with key decision makers and influencers at these customers to ensure a stream of future revenues. In other words: By generating revenue they contribute directly to the bottom line. To ensure accountability, they need to track their hours and activities, but all of them can be directly linked to revenues and contributions to profit.

In sharp contrast, salespeople generally fail to see the direct contribution of their marketing counterparts. From the perspective of sales, marketing employees are out of touch with the needs and requirements of individual customers and the many details that salespeople need to deal with when negotiating with customers about specific orders. Instead, in their opinions, marketers spend their time on rather vague strategic activities, such as developing value propositions and building the brand that cannot be directly linked to increased orders or profits. To make matters worse, they are often not held accountable for their activities or specific results, drive around in large company cars, play golf with customers, and draw a larger paycheck to boot! As a result, from the perspective of salespeople, marketing fails to add value to the company and lacks credibility. One marketing executive we spoke with in a technology company lamented how they have to actually justify to their sales colleagues the importance of the work they perform:

“I think that I spend almost 70 percent of my time explaining and demonstrating to sales the added value to the company of what I do.”

All too often, sales will not acknowledge marketing’s strategic focus and try to downgrade marketing to being a producer of product brochures and other sales collateral, that it may call on as and when needed. In these cases, sales sees marketing as a business function that should focus on supporting sales in their daily activities, thus contributing indirectly to the company’s bottom line, if at all.

Problems from the Perspective of Marketing

In a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface, finger-pointing and blame games usually go both ways. Just as sales fails to see the added value of marketing, marketing employees question what sales is doing. In many B2B companies, because of their daily interactions with individual customers, salespeople have developed close relationships with their customers. As a result, they consider themselves the exclusive owners of these customer relationships and act accordingly. This means that if their marketing colleagues express a desire to meet with customers, it is met with either a lukewarm response or sometimes outright resistance.

While discussing her experience in this regard, a marketing manager at a computer manufacturer told us how he experienced blatant resistance from his sales colleagues when he announced that he would like to meet some customers. He traced it back to a deep sense of distrust between sales and marketing in his company.

“When I had just started in my new job as marketing manager and announced that I wanted to visit a number of customers, the salespeople strongly objected. ‘What are you going to do with my customers?’ they asked me.”

Because of their long-term strategic focus on markets and customer segments, marketers feel that salespeople use a rather limited perspective on satisfying the immediate wants and needs of individual customers. This short-term operational perspective causes them to lose sight of long-term strategic issues, such as building the brand, developing viable competitive value propositions, identifying new market opportunities and developing a continuous stream of innovative products and services. The short-term perspective of sales may generate immediate revenues and profits, but fails to contribute to a sustainable market position in the long run.

Problems from the Perspective of the Sales-Marketing Interface

The effects of stereotypical thinking by sales and marketing employees are most visible from the perspective of the interface where representatives from both functions interact with each other. The most common symptom of a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface is a breakdown in communication between both functions. Many companies must deal with blame-games, misunderstandings, frustrations, and irritations between their sales and marketing employees. In communicating with their counterparts, these employees just do not feel appreciated and understood. In the words of a marketing manager in an engineering component manufacturing company:

“Our salespeople are clueless most of the times…they will constantly look for excuses why they cannot meet their quotas and more often than not, it is the marketing department’s fault. We have had many heated arguments with the sales leadership…they just do not want to take ownership.”

But it can get much worse! In more extreme cases, companies must deal with open conflict, outright hostility, antagonism, and blatant fights. As a part of our research, we spoke with the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) at a foods company. She told us how important it is for companies to deal with the conflicts between sales and marketing in a timely manner, because if left unattended, they may slumber for a long time and take on a life of their own, with participants no longer remembering what caused the conflict in the first place. She talked about her experience of how, a few years ago, marketing had to pull the plug on a sales promotion activity with three major grocery chains for financial reasons. Obviously, that did not go well with the sales organization since salespeople had done extensive preparatory work ahead of that sales promotion activity, and had to face unhappy buyers, who no longer wanted to trust them. As her quote below suggests, salespeople in her company still remember that incident, even after three years, and it continues to color their interactions with marketing, even when things are working smoothly ever since.

“Sales organizations have a very long memory…and they do not forget events easily, especially those where marketing has let them down. After that sales promotion fiasco three years ago, my team has tried many things to reassure our sales colleagues that it will not happen again…but I know that no matter what they say, they continue to harbor a sense of distrust toward us…and they do not necessarily take whatever we promise at face value.”

Whether the conflicts between sales and marketing are open and verbal or more hidden and subtle, they inevitably become evident in a lack of mutual support and collaboration.

Salespeople do not participate in marketing activities and as a result, sales buy-in of marketing initiatives is low or non-existent. Marketing employees have no interest in the approaches used by sales to convince individual customers and focus on developing a strategic perspective on the needs of market segments. In the worst-case scenario, sales and marketing operate at cross-purposes and actively sabotage each other’s efforts. At best, both functions focus on their own activities and ignore each other, which is illustrated by the following remark by a sales manager in a major engineering company.

“We don’t really share a close relationship with our marketing counterparts. If there is a problem that I need solution for, I would try to find a solution myself rather than asking marketing for help. I know I have to get my work done and no one in marketing is really going to understand what my issues are.”

A lack of collaboration between sales and marketing is usually accompanied by a lack of integration of activities. As we discussed in Chapter 1, in today’s hypercompetitive market, marketing and sales activities are supposed to be interdependent and complementary, with marketing focusing on long-term strategic activities that lay the groundwork for effective short-term sales approaches, and sales personnel providing marketing with regular market feedback that goes into developing strategies.

Unfortunately, the reality is often very different. Sales and marketing initiate their own activities and set their own priorities, without consulting each other. As a result, the company’s long-term strategic commercial activities are detached from its short-term commercial activities, causing disconnected processes. For instance, in many companies, sales and marketing develop and use their own customer databases and information systems, which do not communicate with each other. Such a disconnect between the two systems means that marketing has no idea what happened to the sales leads that it provided to sales and that sales ignores the help offered by marketing.

Problems from the Perspective of the Company

Obviously, the effects of a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface have implications beyond the interface itself. At the company level, a less effective interface between sales and marketing has two types of impacts on business performance.

First, and most noticeable, are the wasted resources. When the sales and marketing functions are aligned, sales and marketing support each other in achieving both functional objectives and corporate goals. Marketing provides sales with high-quality sales leads, critical macro-level market insights, and useful sales support materials, such as product brochures, websites, and sales presentations. In return, sales provides marketing with real-time information about changing customer requirements and other relevant market information. When sales and marketing are not aligned, the activities from both functions fail to reinforce each other and result in wasted resources. For instance, marketing may provide sales with sales leads and support materials that look very promising and useful to them, only to find them ignored by sales, who develop their own sales leads and support materials. Or salespeople communicate detailed product suggestions from customers to marketing, which are then dismissed by marketers as non-representative opinions from individual customers. In all these situations, the initial effort is largely wasted and represents an inefficient use of corporate resources. To further exacerbate the situation, when employees notice that their work is not appreciated by their colleagues, or that colleagues provide them with irrelevant information or support, it also has a demoralizing effect on the employees involved.

Second, a dysfunctional relationship between sales and marketing may also lead to missed market opportunities. When a company’s sales and marketing functions are not aligned, it is less effective in developing and delivering superior value to customers, identifying market opportunities, and quickly responding to changing market conditions. For instance, when the first signs of changing customer requirements are noticed by sales but not addressed by marketing, the company will be slower in crafting an effective response or miss embryonic market opportunities altogether. Also, ineffective communication between marketing and sales often results in inconsistent communication to customers, which in turn leads to customer confusion and lower revenues.

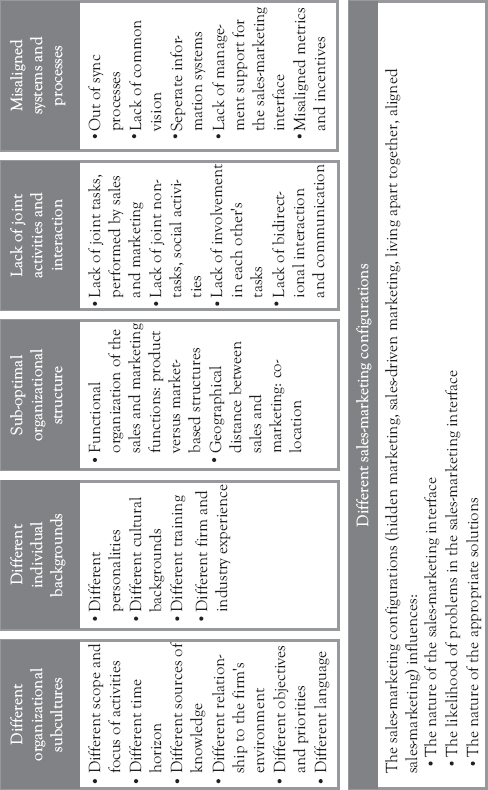

Now that we have identified the symptoms of a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface, we can dive deeper and explore the root causes of these problems. While some of the underlying causes are directly related to the symptoms, others are more deeply rooted in the fabric of the interfunctional relationship or the personal characteristics of the individuals involved. We classify the root causes of ineffective sales-marketing relationships into five groups (Figure 3.2):

1.Different organizational sub-cultures

2.Different individual backgrounds

3.Sub-optimal organizational structure

4.Lack of joint activities and interaction

5.Misaligned systems and processes

Cause #1: Different Organizational Sub-Cultures

Effective customer-centric companies require close cooperation and coordination between the various business functions. For instance, information about changing customer needs collected by salespeople needs to be communicated to the company’s marketing and business development groups, where it is combined with insights from manufacturing and purchasing to make decisions regarding product modifications or the development of new products or services. Unfortunately, all these business functions do not always cooperate well together.

Figure 3.2 Root causes of dysfunctional sales-marketing interfaces

For example, think about the marketing and R&D functions.1 Marketers tend to be extrovert and aim to work with the customer, whereas R&D employees are more introvert and focused on developing superior products and new technologies. These differences are reflected in stereotypical thinking about each other. For example, marketing tends to perceive R&D as inward-focused, spending too much time on developing new products and not having the faintest idea about customer needs and the concept of competitive advantage. R&D, on the other hand, perceives marketing as outgoing, too focused on what customers say (who, in their opinion, do not know what they want anyway!) and too eager to accommodate customers by yielding to specific requests without having any clue about the consequences of incorporating customers’ suggestions into current products.

Cultural Differences between Sales and Marketing

Marketing and R&D represent two sides of an organization that are worlds apart as we outlined above. Therefore, while detrimental, it is not surprising to witness these two worlds clash violently at times.

But it is a different story for sales and marketing. A company’s sales and marketing functions are both externally-oriented, aspire to serve customers and consist of extrovert people, with similar educational backgrounds who have (likely) had similar academic training. Nevertheless, numerous studies have found that sales and marketing often fail to get along and point to different cultural thought worlds as the main reason for dysfunctional sales-marketing interfaces, which are characterized by a lack of cooperation, distrust, and the same kind of mutual negative stereotyping.2 Researchers have examined the cultural drivers of the tensions between sales and marketing within B2B companies3 and the findings bring forth the following insights:

a. Sense of reality: Salespeople and marketers have different organizational roles, resulting in different scopes of activities. Salespeople interact on a daily basis with individual customers to understand their requirements and offer the best solutions. Marketers, on the other hand, look at market segments that represent the aggregated wants and needs of a somewhat homogeneous group of customers. In a B2B marketing environment, “Marketing people talk to … business end-users, while salespeople typically spend their time with distributors and purchasing agents. Marketers deal with market segments and specific product groups. Sales, however, sees the world account by account…. Sales does not fret over analyzing data. Marketing never has to sweat over a customer’s demands on price and terms.”4 It is not surprising then that sales and marketing view reality differently.

b. “Right now” plan versus future plan: Because of different job descriptions, salespeople and marketers have different relationships with the concept of time; that is, they use different time horizons. Sales focuses on customers’ current experiences and immediate needs, and are always looking for what they call a “right now” plan. Marketers, on the other hand, have little regard for the day-to-day problems of customers and focus on long-term, future strategic brand building and product positioning plans.

c. Sources of knowledge: Marketing perceives sales as collecting short-term individual customer information and focusing on customers’ current experiences, whereas marketing is more future-oriented. Sales, on the other hand, criticizes marketing’s lack of customer contact and lack of experience with local concerns of individual customers. Marketing is perceived as improving theoretical knowledge at the expense of the practical.

d. Interaction with the environment: The differences between sales and marketing result in different ways they adopt to interact with the business environment. Sales tends to rely on past practices in responding to immediate concerns of individual customers. Marketing, on the other hand, looks for new approaches to drive the marketplace in search of growth and higher margins.

These differences between sales and marketing are reflected in the language used by both groups of individuals. Salespeople talk about consultative selling and closing deals; marketers talk about building brand equity and designing seamless customer experiences. Even when they use the same words, they often mean different things. When a salesperson talks about a customer, he generally refers to his specific contacts: The decision makers and influencers involved in making the next purchasing decision. But when a marketer talks about a customer, she refers to the entire customer organization as a source of future revenues and opportunities for increasing share-of-wallet. Combined with stereotypical thinking about each other, these semantic differences contribute to misunderstandings and if unchecked, grow into larger interface tensions.

The effects of different subcultures are not always harmful; they also have a positive effect on functional performance and creativity. Salespeople all face the same challenges and are known to band together to derive strength, support, and inspiration from each other. Especially when their commission is partly based on the performance of the entire sales team, sharing best practices improves the effectiveness of individuals and contributes to the subculture of the sales group. Different subcultures also represent a diversity of perspectives on marketplace issues that represent complementary insights and improves the quality of team decisions. It is only when people from different subcultures, such as sales and marketing, are unable to cooperate and communicate effectively that subcultures have a detrimental effect on business performance. A large-scale study of cultural differences between sales and marketing in seven industry sectors in Germany found that a dialog between more product-oriented salespeople and marketers acting as the customer’s advocate enhances market performance. For example, salespeople may be tempted to equip a new product with too many features if they are not counterbalanced by marketers who worry about overcharging the customer.5

Cause #2: Different Individual Backgrounds

The interaction between sales and marketing personnel is not only determined by the existence of separate subcultures in the two functions, but also by the individual characteristics of sales and marketing personnel. We discuss three variables here.

Different Personalities

Marketing and sales jobs are very different from each other. Marketing is all about thinking strategically about the needs and requirements of market segments, different ways of meeting them, and opportunities to distinguish your products and services from those of the competition. It requires an analytical mind that is able to sift through large amounts of information in search of ways to better serve customers and beat the competition in the process. In contrast, sales jobs involve daily interactions with customers about prices, customization, and delivery schedules, as well as building effective relationships. Salespeople need to be tough to overcome customer objections and deal with rejection, persevere through difficult negotiations, and empathize with the wants and needs of individual customers.

Because of these different job descriptions, marketing and sales attract different personality types. People that favor a marketing job tend to be analytical, data-oriented, and focused on team leadership and long-range problem-solving. They are all about building a sustainable competitive advantage and judging projects objectively. But all of this is done behind their desks and not very visible to others. People that go for a job in sales, on the other hand, tend to be people-oriented and focused on succeeding based on individual strengths. They excel at building relationships with people and are not fazed by rejection. They operate in the field and keep moving from one sales opportunity to the next.6

Cultural Origin

Scholars of organizational behavior recognize that the actions and attitudes of employees are not only shaped by their organizational context (such as the subculture of the organizational unit they are a part of), but also by many other groups that provide them with cultural frames of reference. Friends, family, sport clubs, and hobby groups all come with their own values and norms that influence an individual’s behavior and attitudes. All these values and norms contribute to an individual’s personal belief system, which means that they also influence how an individual behaves in an organizational context.

A familiar example is an individual’s national culture; a variable that is increasingly relevant in today’s business context owing to the flattening of the world and the subsequent emergence of a multi-national, multi-cultural employee base in many large, multi-national companies across the globe. A significant body of research describes and analyzes the differences that exist between national cultures.7 The cultures are distinguished as:

1.Individualist cultures, such as the United States, that emphasize masculinity and achieving individual goals.

2.Relationist cultures, such as the Netherlands, that accentuate relationships between people and achieving consensus or compromise.

3.Collectivist cultures, such as Japan, that place collective needs above individual needs and strive for consensus.

A national culture provides a context that shapes an individual’s self-concept orientation; whether he thinks of himself as being separate from others (individualist), linked to others through relationships (relationist), or being part of a larger group (collectivist). This represents an individual’s innate self-concept orientation, shaped by the culture in which he grew up, which influences his actions and attitudes to a significant degree, no matter which part of the world he works in.

In our study of sales-marketing interfaces we found remarkable differences between the US and the Netherlands. US sales and marketing personnel often do not mince words while talking about their counterparts. They openly talk about their distrust of, and sometimes outright hostility toward their counterparts. Salespeople may refer to their marketing colleagues as “sales prevention department” or “unhelpful cost center,” as one sales manager from a pharmaceutical company told us.

“[Salespeople] see marketers as simply pushing their own agenda…with no regard for salespeople’s priorities or concerns…and that sets the stage for a great deal of hostility…there is no mutual respect within this interface. Many of my salespeople will tell you in private that they do not really see any reason why our company should even have a marketing department. They see no value-add.”

In sharp contrast, Dutch salespeople and marketers, in spite of their inherent differences, assume a much softer stance when talking about their counterparts. They emphasize their drive to achieve compromise and join forces for the greater good, as is illustrated by the following quote from a marketing manager in a large telecommunications company:

“You can look at it as playing a game, but you don’t play against each other, but against the competition. Marketing should be a coach for sales, who advises how the game can be played better and what should be done to win in the long run. As a marketer you should have a service attitude towards sales. As soon as marketers start to act like they know it all, like they are making the plans and sales implements them, they no longer fit in the current Dutch situation.”

But this innate self-concept orientation is not set in stone and may change depending on the circumstances. The characteristics of a specific situation may cause an individual to modify his innate self-concept orientation. Psychologists call this phenomenon priming, where people activate a specific self-concept in response to exposure to a specific stimulus, such as interaction with other employees in the organization. Simply put, the presence of colleagues from another group may cause an employee to behave differently. For instance, although US salespeople tend to emphasize individual goals, during their interactions with fellow salespeople they may offer support to each other and work collectively to find a solution to their common problems. Thus, their innate individualist self-concept is modified into a more relationist self-concept when they interact with their sales colleagues. In sharp contrast, their interaction with marketers is governed by different objectives and thought worlds and a strong sense of “us versus them” phenomenon which only reinforces their innate individualist self-concept.

Experience and Training

Individual differences may also be based on different experiences. Marketers frequently change jobs and move across industries, which provides them with a broad experience base. But at the same time they lack detailed knowledge of the industry they happen to work in and the wants and needs of its customers. In contrast, salespeople tend to work much longer for the same company or in the same industry, which provides them with more in-depth insight and valuable relationships. The role and importance of company- and industry-specific knowledge differs across countries. In the Netherlands, business-to-consumer marketers frequently change jobs, but B2B marketers are much more loyal to their companies. In addition, it is not uncommon that B2B marketers have prior experience working in sales at the same company, which further reduces the psychological distance between sales and marketing.

In addition to the experience gained in the current or previous jobs, the training that someone received also influences the attitudes and skills he brings to the sales-marketing relationship. Companies offer a large variety of training to their employees to teach them narrow or broadly applicable job-related skills. Companies that want to improve their customer centricity, so that they are better able to develop and deliver superior value to customers, need to teach their employees how they should interact with (a) business partners who contribute to their value-creation processes, (b) customers, to better uncover the jobs they are trying to do and the problems they encounter, and also (c) their colleagues to assess new market opportunities and craft effective responses. The last type of training relates to the sales-marketing interface. For instance, salespeople and marketers need to learn about each other’s objectives, concerns and activities to become better discussion partners, create a collaborative atmosphere, and facilitate communication between them. Salespeople must be trained in basic marketing principles and taught key concepts such as customer value, market segmentation, positioning, competitive advantage, and marketing strategy. Marketing employees need to be taught about effective sales approaches, the impact of situational characteristics on the needs and requirements of individual customers and the typical problems and concerns of individual decision makers and influencers.

Cause #3: Sub-Optimal Organizational Structure

A company’s structure, how the different entities within a company are organized, may serve as an underlying cause of an ineffective sales-marketing interface. Two aspects of an organization’s structure that directly shape the sales-marketing interface dynamics are: (a) the functional organization of the sales and marketing functions and (b) the geographical distance between the two functions.

Functional Organization of Sales and Marketing

A company’s sales or marketing department may be organized around products or customers. Many companies structure themselves around products. This allows salespeople to specialize in a few related products and is particularly suitable for companies with a wide range of products that require much application knowledge. A disadvantage is that such a structure reinforces a focus on selling existing products to existing customers. In contrast, other companies opt for a market-based organizational structure, with sales and marketing personnel structured around customer groups, with each group served through different salespeople or sales channels. For instance, when each large customer is served through a dedicated key account manager, several medium-sized customers are visited by a salesperson, and small customers are directed to the corporate website where they can place their orders. Another alternative is to use dedicated salespeople for customers in specific industries, such as manufacturers, hospitals, and schools. This allows them to become industry experts with much context-specific knowledge and relevant contacts. An organization structured around customer groups enhances an orientation towards satisfying customers and looking for ways to create more value for them. Many companies discovered that changing market conditions force them to switch from a product-focused structure to a customer-focused one. For instance, in January 2007 the largest Dutch telecom company, KPN, announced that it would implement a new organizational structure in the Netherlands. “This organization is now built around customer segments rather than around products, creating a customer centric organization. KPN’s former Fixed division (“Fixed”) and KPN Mobile the Netherlands (“Mobile”) have made way for new Consumer, Business and Wholesale & Operations segments. … (This is) a further evolution of KPN’s strategy for increasing customer focus in a telecommunications world in which distinctions between technologies are fading rapidly and in which customers increasingly are looking for integrated propositions.”8

If a company’s sales department is organized around products and its marketing department is organized around customers, this will exacerbate the inherent differences between both organizational units. Sales’ product focus contributes to a short-term focus on overcoming customer objections, obtaining orders and generating short-term revenues. Marketing’s customer focus, on the other hand, reinforces its traditional emphasis on satisfying customers, identifying new opportunities for value creation and increasing long-term customer satisfaction. Such mismatches in functional orientation widen the gulf between sales and marketing.

Geographical Distance

It is common sense that the geographical distance between different groups of people in an organization directly impacts the frequency and (likely) quality of their interactions. In the sales-marketing world, geographical distance is an unavoidable reality. In a majority of companies, marketing personnel are based in headquarters, while the members of the sales organization are spread out across the country. As a result, within the marketing group, there are plenty of opportunities for marketing personnel to interact with one another formally or informally. The geographical distance creates a challenge for sales organization. Owing to the fact that they are spread out across a wide region, there are limited opportunities for sales personnel to meet with one another or their marketing counterparts. As a consequence, it is not uncommon for sales and marketing personnel to meet only 2 to 3 times a year in large group settings, that rarely afford them an opportunity to get to know each other personally. Such limited interaction does not allow sales and marketing personnel to build a personal rapport with one another, thereby diminishing the quality of dialog between the two functions.

Recognizing the importance of bridging the physical distance, many companies have experimented with their office spaces to stimulate interpersonal, and especially interfunctional interactions. During his time at Pixar, Steve Jobs had the building designed to promote encounters and unplanned collaborations. “If a building doesn’t encourage that, you’ll lose a lot of innovation and the magic that’s sparked by serendipity…. So we designed the building to make people get out of their offices and mingle in the central atrium with people they might not otherwise see.”9

Even though a large part of the sales organization is geographically dispersed, senior sales leaders usually operate out of the company headquarters. In such cases, it is important for companies to allocate office spaces to its sales and marketing personnel who are at headquarters in such a way that it triggers unplanned encounters and facilitates discussions and interactions that would otherwise not occur. One sales manager we spoke with in a capital equipment company shared his personal experience in this matter. He talked about how having an office at the headquarter location helps him to hold timely conversations with his marketing counterpart and nip any thorny issues in the bud.

“Marketing is located just down the hall from sales. So, whenever there is a problem, I just walk into the marketing manager’s office to discuss it. That’s why we don’t really have any problems in our communication. Everything is being taken care of before it can become a problem.”

Does this mean that simply removing physical barriers and bringing people together will promote casual interaction? Not always; there is evidence that suggests that open spaces may reduce privacy, which may actually limit informal exchanges. As a result, “the most effective spaces bring people together and remove barriers while also providing sufficient privacy that people don’t fear being overheard or interrupted. In addition, they reinforce permission to convene and speak freely.”10 Thus, in order to forge effective, informal interactions within any physical space, the following three factors must be kept in mind:

•Proximity: Physical distance between people is important, but also the distance from things such as entrances, restrooms, stairwells, photocopiers, and the water cooler. The social geography of a space is just as important as its physical layout.

•Privacy: People must feel confident that they can speak freely, without being overheard. Informal interactions will not flourish if other people keep dropping in and the flow of interaction cannot be controlled.

•Permission: Informal interaction will only be stimulated if the company culture designates the space as appropriate for such interactions. Is a discussion at a photocopier considered appropriate or does the company culture make it clear that all “real work” is done at a desk or in a meeting room?

While these three factors relate to the design aspects of an effective office space, the concepts of “privacy” and “permission” are also overarching principles to forge proximity among sales and marketing employees, whether or not they work at the same location. A dedicated focus on these principles is likely to forge effective interactions and collaborations.

Cause #4: Lack of Joint Activities and Interactions

Another major cause of a dysfunctional interface between sales and marketing is that the people involved simply do not work together, fail to communicate, or both. Much of this lack of interaction may be traced to the underlying organizational structure.

Many companies organize themselves around functional silos—such as marketing, R&D, manufacturing, sales—by grouping people together because they perform similar tasks or possess the same skills. Each functional area is put into a separate organizational unit or department, managed by a department manager. The benefits of such a functional structure are obvious: By having all birds of a feather flocking together specialized tasks are performed efficiently and employees have an obvious career path for growth and promotion. Such an organizational arrangement works especially well for companies selling only a single product or service in a stable business environment. Unfortunately, stable business environments have become quite rare and most companies sell multiple products. As a result, many companies have experienced firsthand the negative consequences of functional silos, two of which are elaborated upon here: Absence of bidirectional communication and lack of joint activities.

Lack of Bidirectional Communication

A functional organizational structure creates short communication lines between people within a functional area, which allows for quick decision-making about functional issues. But in today’s fast-changing markets, communication needs to cross functional boundaries, with people from various departments working in cross-functional teams to develop new products, create effective marketing strategies and implement complex multiple channel structures. The real-life stories from Chapter 2 illustrate how a lack of bidirectional communication hinders the free flow of information between sales and marketing and keeps both groups from providing constructive feedback on each other’s work. Marketers need input from salespeople during the groundwork stage to develop effective marketing strategies and tactics, as well as constant feedback from them during the follow-up stage to increase the likelihood of these plans and tactics being successful. Similarly, salespeople need the support of marketing to provide them with compelling value propositions that they can use to convince the customer and to develop alternative strategies and tactics when market circumstances change significantly. As in any personal relationship, a lack of bidirectional communication is a breeding ground for misunderstandings, tensions, and conflicts that sour the relationship between sales and marketing and ultimately limit the value provided to customers.

Lack of Joint Activities

A functional organizational structure easily results in a lack of joint activities between employees from different functions. For instance, R&D employees develop new products and marketing personnel design compelling value propositions and communication strategies for them, but if both groups work within their separate functional silos disconnects are bound to occur. Similarly, in service companies the less than ideal relationship between the customer-facing front office and the operations-focused back office frequently results in suboptimal interfaces that have a negative effect on both employee morale and the value delivered to customers. Apparently, the service orientation of marketers and the efficiency focus of operations employees do not mix easily! Despite the greater similarities between sales and marketing personnel, a lack of actual interaction in the form of joint activities also breeds distance between these two groups of employees. As demonstrated in Chapter 2, marketers and salespeople need to collaborate in developing and implementing effective marketing strategies and tactics. Dividing responsibilities along traditional lines, with marketing developing new strategies and sales implementing them, does not work because sales does not feel invested in the new strategy.

Because of their job descriptions, marketing and sales personnel use different perspectives on customers and markets. Marketers look at the characteristics and trends of market segments while salespeople focus on the requirements and wishes of individual customers. Thus, even though both groups focus on customers, the different job descriptions and objectives result in perceived psychological distance and a lack of understanding. A lack of joint activities, whether it is task-related activities such as joint customer visits by marketing and sales or social activities such as a joint beer and barbeque on a Friday afternoon, further increases the disconnect between sales and marketing.

Cause #5: Misaligned Systems and Processes

The right organizational systems and processes support an effective sales-marketing interface, which helps translate “a vision of the ideal customer value to effective customer interactions.”11 It is therefore no surprise that a fifth, and final cause of dysfunctional interfaces between sales and marketing are misaligned organizational systems and processes that impede the creation of smooth customer journeys. We discuss five ways in which misaligned systems and processes may manifest themselves in a company and affect the interface.

Lack of Common Vision

For sales and marketing to operate as two aligned functions, with each performing their own activities and working towards the same corporate objectives, requires a common vision. In many companies this common vision is absent or playing second fiddle to the objectives and priorities of the functional domain. A company’s common vision describes its identity and the corporate values it embodies. For instance, Wells Fargo uses five primary values: People as a competitive advantage, ethics, what’s right for customers, diversity and inclusion, and leadership. These values capture Wells Fargo’s vision and in their words, are used to “guide every conversation we have, every decision we make, and every interaction we have among our team members and with our customers.”12 This illustrates how a common vision, formulated at the corporate level, serves as a guideline for decisions and activities at the functional level. As the Wells Fargo website continues: “If we can’t link what we do to one of our values, we should ask ourselves why we’re doing it. It’s that simple.” It other words, the company’s vision serves as a guidebook and corporate glue that helps employees at the functional level (such as marketers and salespeople) to align their activities and decisions both with each other and with corporate goals. If this corporate glue is absent, employees and decision makers in the sales and marketing departments are bound to set their own priorities, make their own plans and carry out their own activities, without considering how they fit with what people in their counterpart function are doing and how it all contributes to achieving corporate objectives.

A company’s corporate vision and values are formulated by the company’s management team. But just formulating a vision and publishing it on a corporate website and in some fancy corporate brochures is not enough. The management team also needs to actively ensure that the priorities, decisions, and activities at the functional level align with its corporate vision. In the context of the sales-marketing interface it is all too common that functional departments are run like corporate fiefdoms because management fails to enforce a corporate vision by promoting communication and collaboration between the company’s functional departments. It is management’s task to ensure that the organizational culture and infrastructure supports interfunctional communication and collaboration.

Out of Sync Processes

Although sales and marketing perform different sets of activities, as we have discussed in the preceding chapters, these are closely related and interdependent. For instance, marketing provides sales with all kinds of support materials, such as brochures, sales presentations, case studies, calculation sheets for customer savings, and downloadable marketing materials. These sales support products are designed to help the sales force to be more effective in presenting the company and its products to customers, respond to objections, convert sales leads into orders, and develop customer relationships. This requires a close match between what marketing develops and what sales requires and the timing of it. In practice, marketing’s sales support process and sales’ sales process are often out of sync, resulting in marketing developing sales support materials that sales does not use.

Similarly, as we illustrated in Chapter 2, marketing’s strategy development process needs to be closely linked with sales’ strategy implementation process. Sales may be very proficient at implementing a marketing strategy, but if that strategy is inherently flawed, or meets with unexpected headwinds, the result will not be positive. In the same way, a new brilliant marketing strategy will not be successful if the sales organization is unable or not motivated to implement it effectively. There may be multiple causes for a mismatch between the processes that marketing and sales follow during strategy-making, for example:

•Sales and marketing work independently to achieve optimization for their own processes and ignore the linkages between their processes.

•Sales and marketing fail to communicate while developing respective processes.

•Sales is not motivated to use input from marketing, for instance sales leads, because they do not see its added value.

•Marketing does not listen to sales and views sales as just the operational appendage of marketing.

Separate Information Systems

In a truly customer-focused organization the various departments all work toward creating superior value for the customer, a goal that is supported by the appropriate organizational infrastructure. In today’s hyper-connected world, a key element of that supportive infrastructure consists of the company’s information systems, where all relevant information about customers (both hard data about customers’ interaction histories and soft data about decision makers’ characteristics and preferences) is combined to create a 360-degree view of customers. In the ideal situation, all decision makers have access to the same customer information. Unfortunately, in the real world this is often very difficult to achieve. The more common reality is that both sales and marketing have created their own databases and both contain information about customers. Because these separate databases are typically not linked to each other, they do not facilitate interfunctional communication and coordination. To make matters worse, both databases usually contain different kinds of information about customers and in many cases they do not even define the customer in the same way! For instance, salespeople will define the customer in terms of their contact persons at customer companies; such as their names, backgrounds, special requirements, key objections, phase in the buying cycle, and communication preferences. In contrast, marketing employees define customers as organizations and they will collect more aggregate customer information about product needs, order histories, customer wishes, installed base, and similarities with other customers. While this serves their functional purposes, both sales and marketing have access to only partial customer pictures and lack a complete 360-degree view of their customers. This limited perspective on customers promotes a focus on optimizing functional processes and likely results in suboptimal customer solutions and business performance.

Misaligned Metrics and Incentives

An old psychological adage states that people’s behavior is determined by what is measured and encouraged. In an organizational context this means that employees will display the kind of behavior that gets measured and rewarded. In other words, organizational metrics and incentives influence how marketers and salespeople interact with each other and act towards customers. For instance, in a customer-focused organization employee behavior should be measured and rewarded on the basis of metrics such as long-term customer satisfaction, because this stimulates the kind of behavior that is in the customer’s (and therefore, your company’s) best interest. But in practice, employee behavior is not always in line with the official organizational vision and values. To illustrate this, take the following simple test with your own salespeople:

Suppose that your salesperson is visiting a customer who presents him with a very specific, rather unusual problem. Also suppose that your company offers a product that is somewhat suitable for this specific situation, but that one of your major competitors offers a solution that would provide a better fit for the customer. What would your salesperson do?

The answer to this question depends on several factors. Some of them have to do with the salesperson’s individual background, psychological make-up, and ethics, all of which can be influenced through your hiring process, training programs, and organizational culture. But the salesperson’s behavior in this particular case also depends on the organization’s metrics and incentives. If your corporate vision promotes customer satisfaction and your salesperson’s compensation largely depends on the customer’s long-term satisfaction, he is likely to refer the customer to the competitor that offers a better solution for this specific customer’s problem. If, on the other hand, your salesperson’s salary largely depends on him achieving his quota, he is more likely to push the company’s own product instead (unless it is getting close to the end of financial year and he has already reached his sales quota for this year).

Similarly, misaligned metrics and incentives also influence how salespeople and marketers interact. For instance, if marketers are encouraged to focus on customer satisfaction and building share of customer, while salespeople are evaluated on the basis of realized sales, this will not contribute to smooth interfunctional communication and aligned marketing and sales activities that, each in their own way, contribute to superior value for customers and advance corporate objectives.

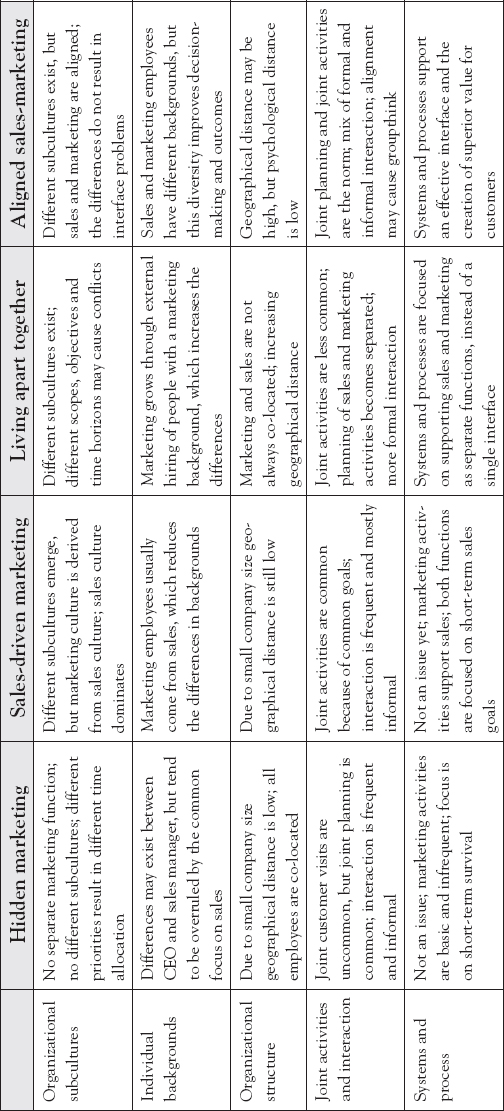

Interface Configuration as Underlying Cause

The likelihood that specific root causes of a dysfunctional relationship between sales and marketing will actually occur in practice is closely related to how the sales-marketing interface is configured in a given company. In Chapter 1 we introduced four basic organizational configurations of the sales-marketing interface: (1) hidden marketing, (2) sales-driven marketing, (3) living apart together, and (4) aligned sales-marketing. We revisit these four organizational configurations here and outline for you how they are closely related to the root causes discussed in this chapter (Table 3.1).

The hidden marketing configuration is most commonly found in small B2B companies lacking the size and resources for a separate marketing department. In addition, the short-term focus on acquiring customers and obtaining orders results in a survival mode in which marketing is seen as a luxury that they cannot afford. Despite the absence of a marketing department, basic marketing activities are still carried out by the company’s CEO or sales manager. For instance, key marketing decisions about which market segments to target and how to position the product. Nevertheless, the absence of a marketing department and the pressures from short-term operational activities and objectives usually result in a very limited marketing function. In practice, this means that the interface between sales and marketing is not very problematic, compared to the other three configurations. There are no different subcultures, because the conflict between sales and marketing is typically a matter of setting priorities, which takes place inside the CEO’s or sales manager’s head. Because of the strong short-term operational focus this usually results in marketing activities taking the backseat to the more pressing sales activities.

Different individual backgrounds are relevant when marketing activities are carried out by the company’s CEO, while the sales manager performs the sales activities. But even in this case, the CEO is usually very focused on sales as well, because of the short-term pressures on the company, which often negate the potential effects of different individual backgrounds. In companies with a hidden marketing configuration, the organizational structure does not cause many problems. Even when marketing and sales activities are carried out by different individuals, the company’s limited size means that geographical distance between them is low and communication is frequent and informal. As a result of the small company size and the low geographical distance, interaction between the individuals carrying out sales and marketing tasks is frequent. Some joint activities, such as joint sales visits, are uncommon because a small company simply lacks the resources. Joint marketing or sales planning, on the other hand, is common because of frequent interactions. Concerning the systems and processes, companies with a hidden marketing configuration are simply too small for this to be an issue. The marketing activities that are performed are so basic and infrequent that there are no separate databases with overlapping, but inconsistent customer information and everything is focused on generating sufficient sales to guarantee short-term survival.

Table 3.1 Interface configurations and root causes of problems

In the sales-driven marketing configuration, a marketing department has been established in response to the increasing demands that are placed upon the sales function. Typically, such an embryonic marketing function is a spin-off from the sales department and strongly focused on supporting sales in its day-to-day activities. In a sales-driven marketing organization marketing is usually operationalized as marketing communications and limited to the most pressing communication tasks, such as producing sales brochures, designing websites, and organizing trade shows. As a result, the subcultures of sales and marketing are both focused on realizing sales and therefore not really different. Because of this short-term sales support orientation, and the fact that the marketing department often has historical roots in the company’s sales department, the psychological distance between the two functions is low, which facilitates interfunctional communications and coordination. Because the company is still relatively small, the geographical distance between the sales and marketing functions also tends to be low, which facilitates frequent and informal communication between the two functions. Because marketing’s primary goal is to support the sales function, joint activities such as joint customer visits and joint planning are common. Finally, the problems that may be caused by misaligned systems and processes are not likely to occur because both functions perform their own activities in pursuit of the same short-term sales goals.

Although the common focus on sales goals in a sales-driven marketing company typically results in a harmonious interface between sales and marketing, this kind of short-term thinking ignores the strategic role of marketing and the implementation of a seamless value-creation process. When this starts to change, the company enters the living apart together stage; the company grows in scope and size, and the marketing department evolves and develops its own identity. In these companies, marketing no longer lives to support the sales department in its daily sales activities, but increasingly focuses on more strategic marketing tasks. For instance, the marketing department may explore unmet customer needs, develop strategic value propositions, and create and grow both corporate and product brands. As a result, the psychological distance between the sales and marketing groups increases and different subcultures emerge, each with their own focus, goals, and language. It is in these companies that the often described misunderstandings, frustrations, and downright hostilities between sales and marketing are most likely to occur. Even when the marketing function started as a spin off from the company’s sales department, by now the marketing group has changed its focus from short-term sales support to more strategic marketing. The growth of the marketing function is largely fueled by hiring new employees with a background in marketing, which drives the two functions further apart.

Because of the increasing separation of the two functions, it becomes more likely that they are organized according to different organizational principles. Increasing company size may also result in marketing and sales no longer being co-located, which further increases the distance between the two functions. Many B2B companies exacerbate the problem by creating separate marketing and sales departments, with the sales vice president often outranking the senior marketing manager.13 The increased geographical and psychological distance between sales and marketing is often accompanied by fewer joint activities and sales planning and marketing planning going separate ways. In many companies, the organizational systems and processes become focused on supporting sales and marketing as two separate functions, without the required emphasis on supporting them as a single effective interface.

In the final interface configuration, aligned sales-marketing, both the sales and marketing groups have established their own identity and their own role in the company’s value-creation process. The difference with the previous interface configuration is that sales and marketing communications and activities are now aligned. The sales and marketing functions still have different subcultures, each with their own objectives and language, but they no longer work at cross purposes. Instead, both functions perform complementary activities and contribute in their own way to the creation of superior customer value, with a balance between short-term operational concerns (aimed at delivering value to customers and generating revenues for the company) and long-term strategic ones (aimed at growing customers and brands). The individual backgrounds of sales and marketing personnel contribute to diversity in thinking and tend to improve the overall decision-making process. Even when the sales and marketing functions are geographically separated, their psychological distance is limited. As a result, the organizational structure supports the efficient exchange of ideas, with both formal and informal communication contributing to an open, ongoing dialog. However, this close alignment between sales and marketing may also result in groupthink with less desirable outcomes. Joint sales and marketing planning results in congruent sales and marketing objectives and many joint activities, such as joint customer visits by a salesperson and someone from marketing. The organization’s systems and procedures are also aligned with an effective sales-marketing interface and support the creation of long-term superior value for customers.

Of course, individual companies will not always exactly fit one of the four types of sales-marketing configurations. Real-life interfaces between sales and marketing functions may exhibit certain characteristics of sales-driven marketing, while other elements of the interface are more typical of a living apart together configuration. It is up to management to identify the company’s position as carefully as possible and use Table 3.1 to:

1.Identify the potential root causes of problems belonging to the company’s current configuration and

2.Explore potential root causes of problems that the company may encounter when it migrates to the next configuration.

So far, we have discussed the need for collaboration between sales and marketing in B2B companies, the often problematic nature of the relationship between the two functions, the nature of the problems between sales and marketing, and the root causes of dysfunctional sales-marketing interfaces. In the next chapter, we will explore a wide range of solutions that companies may implement to improve their sales-marketing interface.

Chapter Take Aways

•There is a wide range of problems that may exist in the relationship between sales and marketing. Some of these problems manifest themselves at the level of one of the functions, while others become evident at the interface or company level.

•The consequences of a dysfunctional sales-marketing interface are experienced at the level of the sales-marketing interface (bad communications, distrust, conflict) and at the level of the company (wasted resources, missed opportunities).

•The root causes of problematic sales-marketing interfaces can be grouped into: different organizational sub-cultures, different individual backgrounds, sub-optimal organizational structure, lack of joint activities and interaction, and misaligned systems and processes.

•The different subcultures of sales and marketing relate to different tasks, objectives, and outlooks. These differences often hinder effective communications and collaboration.

•In addition, sales and marketing personnel tend to differ in terms of their psychological make-up, which further complicates effective interactions.

•Company characteristics also influence the relationship between sales and marketing. For instance, its corporate structure and processes and systems should facilitate an effective interface.

•As always, unfamiliarity breeds resistance. This means that a lack of joint activities and interaction also increases the psychological distance between the sales and marketing groups.

•The importance and prevalence of these root causes are directly related to how the sales-marketing interface is organized in the company (that is, which of the four basic interface configurations is used).