PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Building Your Skills While Doing Meaningful Work

We can change the world and make it a better place. It is in our hands to make a difference.

—NELSON MANDELA

Conversational capacity is a skill-based competence and building it requires practice. (If you don’t need practice to acquire an ability, then it isn’t a skill.) To that end, it’s now time to put what you’ve learned to work.

As I said in the Introduction, the purpose of this book is twofold:

• First, to help you build your personal conversational capacity.

• Second, to build a healthier and more productive workplace by doing work that makes a difference.

The first step is to start looking for opportunities to do this. Is there a relationship, process, or activity that is pivotal to your team’s performance but isn’t working as well as it could? There you go. Is there a problem in need of attention or a conflict to be resolved? If so, there’s another opportunity.

Your goal is to find a place you can initiate a conversation that sparks an improvement in your team, workplace, or community and to use that work as practice to build your conversational discipline. Then, once you’ve identified an issue you’d like to address, the next step is to plan for how to engage it effectively. What follows are a few suggestions for how to do just that. (You may have already identified opportunities for practice, but if not, don’t fret. In the next chapter, we’ll go into even more detail about places to look.)

Three Options

I’m asking you to identify places where there’s a gap between how things are currently working and the potential for greater performance. When you find such a gap—like Steve did in Chapter 1—you’re immediately faced with a question: “What will I do about it?”

You have three basic choices:

1. Put up with it. Live with it. Suffer it. Complain about it, perhaps, but don’t take action to address it. Maybe you’ll get lucky and someone else will take care of the problem, or it’ll just magically disappear on its own.

2. Walk away from it. Quit. Bail. Move on. “I’m sick of all this nonsense. I’m outta here.”

3. Do something about it. Adopt a constructive and responsible orientation and engage the problem, and use that work to expand your conversational competence.

When you choose the third option, in the pages that follow I’ll share four ways to dramatically increase your odds for success:

1. Collaboratively designing a way forward.

2. Putting together a “Conversational Game Plan.”

3. Following the “Basic Discipline” of Conversational Capacity.

4. Facilitating conversations.

What I like to do is try to make a difference with the work I do.

—DAVID BOWIE

Collaboratively Designing a Way Forward

To help you get started, let’s revisit a simple approach I’ve helped many clients employ to improve a wide range of issues: from meetings, decision-making, strategy, and change, to customer service, interpersonal relationships, team dynamics, and management behavior. Collaborative design, the form of inquiry I first introduced in Chapter 13, is the process of cooperatively working through a problem and mutually designing a way to address it. It’s a simple way to structure a conversation about almost any sort of constructive change. I encourage you to consider it as you take what you’ve learned in this book and start applying it to issues that matter.

Guess or Ask

As I pointed out earlier, when you’re making important choices you have two basic options: guess or ask. When you guess, you take unilateral control of the choice, making it based solely on your perspective. When you ask, however, you’re deliberately designing the best way to achieve the goal by allowing the perspectives of others to influence and shape your ideas and decisions. If your mind is a workshop in which you’re producing smart, intelligent, well-informed choices, then collaborative design is a powerful part of your process.

If you decide to improve the working relationship between your team and another team in the organization, for example, you can either guess how to improve the relationship and unilaterally impose your solution, or you can ask others for their ideas, input, suggestions, and concerns and then collaboratively design a way forward. This basic choice is true for all sorts of decisions:

• When deciding how to provide useful feedback to someone, you can either guess or ask.

• When trying to improve your working relationship with a colleague, you can either guess or ask.

• When deciding how to manage your people so they consistently bring their best work to your team, you can either guess or ask.

• When trying to figure out how to provide outstanding customer service, run better meetings, orchestrate change, resolve conflicts, bolster innovation, improve a “baton pass” between people or groups, or generate more trust, you can either guess or ask.

More Of? Less Of?

If you adopt a collaborative approach, you can start by stating the problem you’re facing and a basic goal, and then pursue the best ways to bridge the gap between the two. A simple inquiry you can use to start off the conversation is this: “What do we need more of and less of to get from point A to point B?”

One team, for example, engaged a challenge this way: “Our meetings receive a steady stream of harsh complaints in our monthly employee survey. They’re seen as a big waste of time. So here is what I’d like to explore as a team: What do we need more of and less of in our meetings so they’re half as long and twice as effective?”

They then used the discussion about that question to practice the skills. They started with a conversation focused on the first part of the issue: “What about our current meetings limits their effectiveness?” before moving on to a conversation that focused on solutions: “What changes would help us meet our goal of meetings that are half as long, yet twice as impactful?”

You can adopt the same approach when you raise an issue. Start with the “more of and less of” frame. Then make suggestions if you have them, taking care to explain and test the thinking behind your suggestions. If others disagree or have different views, inquire to learn more about how they’re viewing the situation.

The collaborative approach can be challenging. There are often conflicting perspectives, messy conversations, and hard feedback to digest. But if you’re driven by the need to make the smartest choices possible, asking is the obvious way to go. As one client once put it: “You can either collaboratively design the solution with the people that matter or you can just dumbass it.”

Remember, it’s not about consensus decision-making, or accepting every idea or opinion. It’s about helping make decisions that involve others with more than just your limited perspective as the guide. You’re seeking input, not taking directions.

It’s Not as Obvious as It Seems

You may think this approach is obvious, but it’s far less common than you’d think. Managers often define what makes a good manager—based on the books they’ve read, the classes they’ve taken, or the way they’ve been managed in the past—and then, with good intentions, they impose their definition of a “good manager” on their team. But while their management approach might make perfect sense to them, it may not make sense to the people they’re managing. The managers are then baffled when they receive critical remarks about their management style in their 360-degree feedback. One manager complained to herself: “This ungrateful team wouldn’t know good management if it fell from the sky and hit them on the head.”

Phil provides another example. After receiving feedback that he was too soft on the business, he unilaterally imposed his solution on his team. With the best of intentions, and in a way that made perfect sense to him, he guessed how to solve the problem. It wasn’t until after Steve helped him see how his unilateral approach was creating more problems than it solved that they were able to collaboratively design a more integrated approach to their predicament.

What Are We Doing to Drive You Nuts?

To give you a better feel for what this looks like in practice, here’s an example of the approach being employed in an exceptional way. A program director for an aerospace contractor put together a two-day offsite with their customer, the U.S. Air Force, to improve a strained working relationship. For years, the program had enjoyed a banner relationship between the contractor and their customer, which was held up as a shining example for other programs to emulate. But due to management changes on both sides, things had devolved to the point that the relationship was artificially polite on good days, and acrimonious and argumentative on bad ones. “Both sides are using the contract as a weapon,” the program director told me. He wanted this two-day workshop to help turn the situation around.

Ten people from the aerospace firm and an equal number of officers from the Air Force attended the session. On the morning of the first day, after brief introductions and opening remarks, the program director began the hard work: “As we’ve noted, we’re really hoping to use these two days to improve our working relationship. We know we’re frustrating you. We don’t mean to do it. It’s not part of our strategy. We don’t start every day by trying to figure out how to make our relationship worse. But we know we’re doing it just the same. So to kick-start the process of improvement, we’d like to ask the Air Force a simple question: ‘What are we doing to drive you nuts?’”

There was silence at first, but slowly the officers began to share their concerns. The aerospace team followed up with clarifying questions, such as “Can you explain how that plays out on your side of the fence?” The aerospace team captured key details on flip charts. When the officers realized the executives were genuinely interested in their feedback, the momentum grew, and soon they had several pages of issues to address. After categorizing the topics, they broke into smaller groups to address the details, while working hard to stay in the sweet spot.

On the morning of the second day, a colonel asked if he could have the floor. “We were taken aback by what happened yesterday,” he said. “We came to this event prepared for a fight. We expected you to throw complaints in our face, and we came armed with a big list to throw right back at you. When you went to the board and asked us, ‘What are we doing to drive you nuts?’ that really surprised us. We talked in the bar last night and decided we’d like to ask you the same question: ‘What’s the Air Force doing to drive you nuts?’” The Air Force officers captured key responses on flip charts, and then broke into smaller groups, repeating the same process from the previous day.

At the end of the two days, we conducted an evaluation to see how people felt about the offsite. The biggest complaint? There was not enough time to work through all the issues. There was such low defensiveness and such open and constructive dialogue that they scheduled an additional day the following month to work through the remaining issues. This simple but powerful process—coming together to collaboratively design a way to move forward in a more healthy and concerted way—became a regular part of their program management best practices, and it helped to restore some of the old shine to their working relationship.

Creating a Conversational Game Plan

Okay, you’ve identified an issue you’d like to address, and you want to collaboratively design a solution. The next step is to put together your conversational game plan—how you’ll use the concepts and skills you’ve been learning to structure and facilitate your conversations. To do that, I encourage you to work through the same five-step process that Steve and his partners used to prepare for his conversation with Phil:

1. Identify your conversation. What is the conversation I need to have to address this issue? And with whom do I need to have it?

2. Identify your objectives. What are my goals for this conversation? What’s the problem I’m trying to solve? What is the ideal outcome I’d like to achieve? What do I want to accomplish?

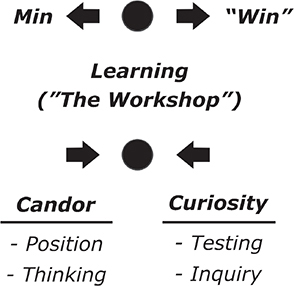

3. Identify your intentional conflicts. What intentional conflicts, or “binds,” will I experience in the conversation? How, for example, might my need to minimize (min) or “win” (or both) make it difficult for me to stay in the sweet spot? What are the potential triggers I need to watch out for? In conversations like this in the past, what has led me to be less effective than I intended to be? (Here are two examples: “I want to be candid in my discussion with my boss, but I’m worried that she’ll react defensively and I’ll back down.” Or, “I want to bring up this issue and work it through with my colleague, but I’m concerned that I’ll trigger my need to ‘win’ and spark an argument.”)

4. Plan out the conversation. Given your responses above, think through the structure of the conversation by considering these questions:

a. What is my position on the issue? How can I explain it in one or two clear, concise, compelling sentences?

b. How can I explain my thinking so that the other person (or persons) can see how I’m making sense of the issue? Why do I think what I think? What examples can I provide to illustrate my position? What evidence do I have? How am I interpreting that evidence? Why do I feel so strongly about this issue? What is at stake?

c. How will I test my view so that others see I’m holding it like a hypothesis rather than a truth? How hard will it be for this person to challenge me, to openly disagree, or to share another way of looking at the problem, and how can I test in a way that makes it more likely they’ll do it?

d. What are possible reactions to my test, and how will I use inquiry to help others get their views on the table? How will I lean into their reactions, especially where they differ from mine, or are not what I expect? What might be two or three realistic responses I can expect from the person, and how will I use inquiry to respond productively?

5. Role-play the conversation. Practice it. Take it for a test- drive. Like astronauts who prepare for a spacewalk by practicing their moves in a neutral buoyancy simulator (or as President Franklin Roosevelt would probably call it, “a big swimming pool”), you can prepare for your conversation by practicing your moves in a role-play. Ideally you do this with a partner or two. But if that’s not possible, mentally simulate the conversation in your head. Imagine the back and forth. Picture yourself enacting your game plan in a focused, disciplined way.

6. Reflect and assess. What did I learn by working through the previous five steps?

• “I keep forgetting to inquire when the other person disagrees with my assessment.”

• “My mind tends to go blank when someone asks me a question that I’m not ready for, so I probably need to keep some notes about my basic view in case I get lost.”

• “What did I learn? I need more freaking practice. That’s what I learned!”

Priming the Conversation

Before you jump into the conversation by stating your position, it’s often helpful to provide a little context so you don’t catch other people by surprise, and perhaps make them unnecessarily defensive in the process. To do this you can prime the conversation by describing the issue you’d like to discuss, what you hope to get out of the conversation, and whether or not they’re is interested in having the conversation. If they’re willing to have the conversation, you can next describe any bind you’re experiencing. In this way, you’re setting a clear context for the discussion and making it far less likely others will misinterpret your intentions. You’re collaboratively designing how you’ll address the issue in the most constructive way possible.

Here’s an example:

• I’d like to talk about the meeting yesterday and provide a little feedback about how you handled it. Is that something you’re interested in talking about? If so, is this a good time?

If the answer is yes, respond with this response:

• My goal here is to be honest and provide some useful feedback so you can make some informed choices about how to move forward. If I come across in a way that’s not helpful, please hit the pause button. That’s not my intention.

If the answer is no, respond with this question:

• Would you be willing to talk about this issue at a later time? If not, is there something about the issue, or about me, that makes you reticent to discuss the matter?

To help you think about how you might set up a specific conversation by providing some context, here’s a simple template:

• To start things off, I have a perspective I’d like to share with you and then get your reaction, especially if you see things differently. Does that work for you?

• I would like a conversation with you about _____________________. I think it is important because _____________________.

• My intention is to spend a little time exploring our views around this issue so we can make some smart choices about how to address it.

• I do feel like I’m in a bit of a bind. On the one hand, I’m eager to explore how we each see this issue, especially where our views differ. On the other hand, I’m concerned about _____________________.

Once you’ve decided on a way to monitor and manage the concern, kick off the conversation with your position and follow the basic discipline. If at any point the conversation starts to move in an unproductive direction, you can harken back to the primer:

• I feel like we’re falling into the trap we discussed before we started. We’re starting to argue and lose curiosity. Let’s hit the pause button like we agreed and talk about where we are, how we got here, and how we can get back on a productive track.

Having the Conversation: The Basic Discipline of Conversational Capacity

The key now is to stay in the sweet spot as you engage in the conversation, or if you leave it, catch it and quickly regain balance. To do this, here is what the basic discipline looks like when it all comes together.

Catch It, Name It, and Tame It

• Catch it. Having cultivated your personal awareness, you’re monitoring your emotional and mental reactions in the conversation. You quickly notice when your min and “win” reactions threaten to separate your behavior and your good intentions.

• Name and tame it. Labeling the emotion helps to “brake” the reaction and gives you more control, so as soon as you catch it, name it and tame it: “There’s my minimizing tendency tugging at me again.” Or “There’s my ‘win’ tendency telling me to argue the point. That didn’t take long.” Remember, just labeling your emotional reaction has a dampening effect that makes it easier to manage.

Refocus and Replace

• Refocus. Naming and taming the reaction gives you the ability to refocus on what matters in the conversation: learning. So, mindset forward, you stay in your mental workshop with your beam of attention focused on making the smartest choices possible. To help you do this, you ask yourself three questions:

• What am I seeing that others are missing?

• What are others seeing that I’m missing?

• What are we all missing?

• Replace. To keep your behaviors in line with your mindset, you replace your habitual min or “win” reactions with the appropriate skills for staying balanced. When your need to minimize is being triggered, for instance, the candor skills—stating your position and explaining your thinking—will help you retain balance. When your need to “win” is being triggered, the curiosity skills—testing your view and inquiring into the views of others—help you stay in the sweet spot. It’s not that you ever stop being triggered, it’s that when you’re triggered, rather than reacting in your habitually defensive way, you choose a more constructive and balanced response.

Reflect and Repeat

• Reflect. Once the conversation is over, reflect on your performance

• How consistent was my behavior with my game plan?

• How well did I stay in the sweet spot?

• Where did I surprise myself by responding well under pressure?

• In what ways did I respond differently than I used to?

• Where did I drop the ball?

• What triggers did I identify?

• I notice I triggered to minimize when ________________. Next time that happens, how will I respond in a more balanced way?

• I notice I triggered to “win” when ________________. Next time that happens, how will I respond in a more balanced way?

• What did I learn about myself?

• What did I learn about the other people with whom I was talking?

• What did I learn about the situation or problem we’re facing?

• What can I do to be more effective in a similar situation in the future?

Here’s an important point: When you fail, don’t get upset, disappointed, or despondent, get curious. View it as an opportunity to break out your trigger journal and reflect, learn, plan, and grow.

• Repeat. This is the last step in the basic discipline. You don’t do this once and stop; you look for another conversation about an important issue to take on. In this way you’re repeatedly practicing conversation-by-conversation, meeting-by-meeting, day-by-day.

Ed Harris

You never fully rid yourself of the defensive reactions that threaten your competence. That’s not the goal. The fight-or-flight tendencies that knock you out of the sweet spot never completely disappear, but you can lessen the power they exercise over your behavior. You can learn to notice them without giving in to them. And by refusing to exercise them, the mental muscles behind them will atrophy from lack of use.

In this sense, you’re like John Nash in Ron Howard’s film A Beautiful Mind.1 In the first part of the film, Nash, a schizophrenic—played by Russell Crowe—has a tendency to establish close relationships with people who aren’t really there. They’re figments of his imagination. They’re delusions.

As Nash comes to term with his illness, he slowly extracts himself from those relationships. They never fully go away; they still loiter around, waiting for Nash to let them back into his life. Ed Harris’s character, the government agent, for example, still lurks around, trying to goad Nash. But while Nash sees him, he refuses to interact with the delusion. By the end of the film, which takes place many years later, Nash is still plagued by his tendency to see people who aren’t really there, but his relationship to his predilection is transformed. He manages his delusional tendencies; they no longer manage him.

Your min and “win” tendencies are like that. They’ll never disappear. You can’t exorcise them. (Nor would you want to, actually. They’re very useful in many circumstances.) No, your “Ed Harris” tendencies will never fully go away, but just like John Nash, with discipline and practice, you can get better at recognizing and managing them.

In this way you’re creating an upward spiral of competence, in which thoughtful and disciplined action is followed by reflection and learning, which in turn leads to even more thoughtful and disciplined action. That’s the practice, the basic discipline of conversational capacity: Find a problem, an issue, or a place to make a constructive difference. Do your homework and engage it. Reflect on the experience to absorb what you’ve learned, both about yourself and about the situation you’re striving to improve. Then, taking into account your new learning, dive back in and repeat the process.

The “Heads-Up Display”

A helpful way to visualize and share the basic discipline is with what I now refer to as the “heads-up display”—or HUD, an idea suggested by a test pilot who attended one of my workshops. This simple diagram, which I put up on a flip chart when I present, covers all three domains of the discipline:

• Awareness. You’re monitoring the reactions—yours and others—that threaten to pull a conversation out of the sweet spot so you can catch it, name it, and tame it.

• Mindset. After you catch it, name it, and tame it, you next refocus on learning by intentionally heading into your “workshop.”

• Skill set. You replace your habitual defensive reactions with the behaviors that keep you in the sweet spot. When you notice someone else has left the sweet spot, you respond in a way that helps keep the overall conversation in balance.

Informal Facilitation

The HUD provides a way to informally facilitate a meeting or conversation, even if no one else in the room is aware of the skills. The test pilot put it this way: “I find that when I’m sitting in a meeting, this simple framework serves as a HUD, or a ‘heads-up display.’ Because I’m ‘looking through’ this framework, I’m now picking up on things I didn’t used to catch, and as a result I have a range of new choices for how to respond.”

The basic idea is to remember Airto Moreira’s description of jazz performance: Listen to what’s being played and then play what’s missing.

• If someone blurts out a strong opinion but doesn’t explain it, for example, invite their thinking into the conversation with inquiry: “You’ve obviously got a strong view on this matter. Take a couple of minutes and explain to the team how you’re looking at the situation.” (One person asking a few great questions in this way can alter the course of an entire meeting.)

• If you notice that someone states a view and explains it, but then fails to test it, just jump in and test it for them: “Leilani put a strong view on the table. I’d be interested to hear from others, especially those who have an alternative view.”

• If you have a concern about an idea someone is proposing, put your concern on the table by stating your position, explaining your thinking, and testing your hypothesis. “I’ve explained my concern and my thinking, so now I’m interested in hearing from those of you who see a flaw in my analysis.”

• If someone isn’t participating in the dialogue, invite him or her in: “Jose, we’ve been bouncing this issue around for a while now. I’d be interested in hearing your take on the decision.”

• If someone is heating up and taking more than their fair share of the meeting, you can help bring more balance to the dialogue: “Rodney’s done a good job of sharing how he’s looking at this predicament in a clear and passionate way. Let’s get a few other perspectives on the table to expand and improve how we’re looking at this situation.”

Formal Facilitation

This heads-up display can also help you to formally facilitate better meetings and conversations. You can use the basic framework, for example, to establish a “Conversational Code of Conduct” for the encounter by providing a few ground rules:

We have several important issues to address here today, and there are strongly differing views about how to address them. We’re not going to get much done if people are shutting down and not participating, and we’re not going to get much done if we’re butting heads and arguing. So that we’re using our time as effectively as possible, I’d like to share with you a simple framework for how we can work together in something called “the sweet spot.”

You can then write the HUD up on the flip chart, explaining the ideas and skills as you go along, and then use them to facilitate the discussion. By using this simple “heads-up display,” either formally or informally, every meeting is smarter because you’re in the room.

Where We Go from Here

I try to practice with my life.

—HERBIE HANCOCK

You’ve now learned a few ways you can turn your workplace into your personal dojo, a space where you can practice and learn every day. I hope you’re feeling more empowered to create a team, workplace, organization, or community that is smarter, healthier, and stronger.

As with any practice it takes a lot of effort at first, but as you build your strength and discipline, it’ll get easier and easier. To that end, it’s now time to take all that you’ve learned and put together a personal plan for how you will build your conversational capacity while doing something challenging and meaningful. In the next chapter, Influence in Action will become more your book than mine.