CHAPTER 10: IMPACT AND ASSET VALUATION

The successful exploitation of a vulnerability by a threat will have an impact on the asset’s availability, confidentiality or integrity. This may have consequences for the business, in terms of its actual operations, or from a compliance angle, or in relation to a contractual requirement. A single threat could exploit more than one vulnerability and each exploitation could have more than one type of impact. These impacts should all be identified.

Risk assessment involves identifying the potential business harm that might result from each of these identified impacts. The way to do this is to assess the extent of the possible loss to the business for each potential impact. One object of this exercise is to prioritise treatment (controls) and to do so in the context of the organisation’s acceptable risk threshold, so it makes sense to categorise possible loss in terms of impact on the organisation of losing the identified asset attribute.

Impacts

Clause 4.2.1 – d4 of ISO27001 requires that the organisation ‘analyzes the impacts that losses of confidentiality, integrity and availability may have on each of the assets’. ISO27001 also requires the organisation to ‘develop criteria for accepting risks and identify the acceptable levels of risk’ (4.2.1 – c2). It provides no guidance as to how those criteria should be developed other than suggesting (in 4.2.1 – e1) that they should be based on the ‘business impacts upon the organization that might result from security failures, taking into account the consequences of a loss of confidentiality, integrity or availability of the assets’.

Furthermore, ISO27001 provides no guidance as to the basis on which control selection decisions should be made, other than to say that the ‘selection shall take account of the criteria for accepting risks as well as legal, regulatory and contractual requirements’ (4.2.1 – g).

Finally, ISO27001 has no requirement in terms of your methodology for the valuation of information assets.

How you value an asset is, however, going to be fundamental to how much you will be prepared to invest in protecting it. ISO27001 simply defines an asset as ‘anything that has value to the organization’ (clause 3.1), but does not specify how that value should be assessed. The organisation’s fixed asset register is unlikely to provide practical help in this regard: many critical assets may already (through application of the financial depreciation policy, or of the accounting convention that assets should be shown on the balance sheet at the lower of historic cost – less depreciation – or current market value) have been written down below their actual useful value to the organisation. Many other, even more critical, assets (such as brand value, key supplier and customer contracts, staff know-how, intellectual property and databases) may not even be on the fixed asset register at all. Many of these assets may even have a current market value in excess of the historic cost and, in some cases, this value appreciates over time, rather than depreciates.

Resolution of these issues is fundamental to the development of an ISMS that will meet the requirements of ISO27001; you must have clearly defined criteria that enable management to ‘knowingly and objectively’ accept risks (4.2.1 – f2). These criteria must reflect some practical relationship between the potential impact of an information asset-related threat on the organisation and the level of investment that will be made to prevent that happening.

These issues are, therefore, fundamental components of the organisation’s risk assessment methodology. As we said earlier, the standard requires the organisation to identify threats to its information assets, the vulnerabilities that might be exploited by those threats, and the impacts that losses of confidentiality, integrity and availability might have on each of those assets.

Furthermore, the results of the risk assessment must be used to inform the correct ascription of controls to assets in light of the value of each asset (i.e. the importance of the asset to the organisation, or the impact on the organisation that would result from a compromise of each of confidentiality, integrity and availability) and the threats and vulnerabilities which, in combination, make up the likelihood of the asset being compromised.

The standard is clear that impacts have to be considered separately for each of confidentiality, availability and integrity, and in each of the business, legal/regulatory and contractual contexts. This is logical because you are likely to select different controls to preserve confidentiality (e.g. encryption) than to ensure availability (e.g. backups). In other words, for any given asset and a specified threat-vulnerability combination (and we will look in more detail at these in the next chapter), you will need to identify the impact on the organisation of a loss of confidentiality, a loss of integrity and a loss of availability.

Defining impact

BS7799-3 recommends (and ISO27005 concurs) that impact ‘values should be identified that express the potential business impacts if the confidentiality, integrity or availability, or any other important property of the asset is damaged’ (clause 5.4). ISO27001 is concerned specifically with negative impacts, to be described in terms of loss or degradation of the confidentiality, integrity or availability of an asset.

Confidentiality is lost when information suffers unauthorised disclosure. ‘Unauthorised’ ranges from breach of data protection or privacy legislation, through breach of contractual requirements, to betrayal of commercially or personally sensitive data.

Integrity is lost when unauthorised changes are made to information or information assets, whether accidentally or deliberately. Failure to repair losses of integrity can lead to further corruption and integrity loss in other information assets.

Availability is undermined when those (people or systems) authorised to access information in order to do their jobs are unable to do so.

This means that each asset should have a separate impact assessment for each of confidentiality, integrity and availability. You should, therefore, identify one-by-one, the likely impacts for each threat-vulnerability combination that you identify for each and every asset within the scope of your ISMS, and for each of confidentiality, integrity and availability.

This has to be taken further. Every information asset is, as we have seen, likely to be affected by at least one threat-vulnerability combination. Every such combination might compromise each of the confidentiality, availability and integrity of the asset, which means that you may have to make three yes/no decisions. For each of the three information attributes, there may be an impact that has business consequences, one that has legal/regulatory consequences, and one that has contractual consequences. You must therefore assess, for each of these possibilities, what that impact might be. You have, in other words, potentially nine decision points in respect of each threat-vulnerability combination for each information asset.

Here’s an example:

Imagine the risk assessment carried out in relation to an organisation’s unencrypted backup tape, and specifically how it is transported to secure off-site storage. A threat – driver forgetfulness or inattention – might exploit a vulnerability – the van door doesn’t close properly unless it is forced shut and locked – with the consequence that the backup tape might fall out into the road while in transit. There is a realistic likelihood of this happening, and the potential impacts can be assessed as follows:

Confidentiality of the information on the backup tape will be compromised; the business’s reputation for protecting its customer data will be undermined and it will lose a quantifiable level of revenue; there will be legal consequences, which can also be quantified, arising from the breach of the privacy of the individuals whose data is on the tape; and there will be contractual consequences arising from the breach in specific customer contracts that require protection of their data.

Availability of the backup tape will be compromised; the business impact may be an inability to continue operations when faced with a business continuity event and this will have quantifiable consequences; the legal consequence may be that the directors are prosecuted for their failure to be adequately prepared to protect the company’s assets; the contractual consequences may include a breach of a customer contractual requirement for effective backup processes.

Integrity of the backup tape may be compromised because the tape may be damaged on falling out of the van while it is in transit; this will have a business impact when it proves impossible to restore the most recent version of a specific user document that has been corrupted in error; it may have a legal consequence when a later court case is unable to access a critical document for which no other copies exist; and it may have contractual consequences if the tape contains data that has to be surrendered to the customer on completion of the contract.

Whilst methodologies do exist that, having determined individual values for these impacts, then add or multiply them together to try to reduce the actual risk assessment workload, practical experience demonstrates that the results produced by these methodologies skew the risk treatment decisions. For instance, an asset with a very high confidentiality impact level and a very low availability impact level needs different controls for risks to confidentiality than to availability. Should you apply controls that are more appropriate for one risk than the other, or should you apply something ‘in the middle’ that is appropriate for neither? In either case, what you have is a situation in which your risk treatment decision is not directly related to the risk, and the investment in the controls is unlikely to be in proportion to the potential impact against which you are guarding. In other words, this sort of approach is unlikely to lead either to an ISMS that conforms to ISO27001 or to one that is cost-effectively optimised.

The risk analysis above doesn’t yet include an assessment as to the actual cost of the impact on the organisation in any of the nine identified areas, nor does it include an assessment as to the likelihood of occurrence of the threat-vulnerability combination, and it is, therefore, impossible to determine which of the identified risks should be accepted, which rejected and which transferred or controlled.

Estimating impact

Part of how we make that decision has to take into account the cost of controlling the risk: should we spend more, less than, or the same as, the potential cost of the impact on controlling the risk?

ISO27001 defines the purpose of an ISMS as ‘ensuring the selection of adequate and proportionate security controls that protect information assets and give confidence to interested parties’ (clause 1.1). ISO27002 goes further. It says:

Expenditure on controls needs to be balanced against the business harm likely to result from business failures. [clause 0.4]

Risk assessment should include the systematic approach of estimating the magnitude of risks (risk analysis) and the process of comparing the estimated risks against risk criteria to determine the significance of the risks (risk evaluation). [clause 4.1]

This is helpful guidance, in that it talks about ‘estimating magnitude’, not ‘quantifying cost’, of risks, and about ‘proportionate’ security controls. This guidance, which is in line with a qualitative risk assessment methodology, is a particularly helpful starting point for considering impact value.

BS7799-3 takes this guidance further: it says that assets should be valued to take ‘account of the identified legal and business requirements and the impacts resulting from a loss of confidentiality, integrity and availability’ (clause 5.1). It goes on to suggest that ‘one way to express asset values is to use the business impacts that unwanted incidents, such as disclosure, modification, non-availability and/or destruction, would have to the asset and the related business interests that would be directly or indirectly damaged’ (clause 5.4). The value of the asset should, in simple terms, be the same as the impact value of compromising it. ISO27005, in talking (at clause 8.2.1.6) about the ‘business consequences if [the assets] are damaged or compromised’, is taking the same view as BS7799-3.

Our earlier analysis of the threat-vulnerability combinations that might compromise a backup tape is in line with the view that assets should have more than one value. BS7799-3 confirms this view: ‘values should be identified that express the potential business impacts if the confidentiality, integrity or availability, or any other important property of the asset is damaged’ (clause 5.4) and suggests that a standard asset valuation scale should be defined for assets to assist asset owners in correctly valuing their assets.

BS7799-3 recommends the creation of an asset impact valuation scale to guide asset owners in their valuation activity. The starting point for the creation of such a scale is to estimate the possible cost of impact. One traditional method (one that we recommend, and which is also contained in ISO27005) of estimating impact is to identify, value and aggregate all the direct (e.g. legal) and indirect (e.g. brand diminution) costs of an event, all the costs of recovery, repair, rectification and (possibly) lost opportunities and lost revenue. The resulting total cost of (potential) loss is the impact value.

A stepped set of impact levels (e.g. high-medium-low) can then be designed that reflects the ranges of estimated impact, such that, for instance, all impacts with an estimated cost between £15k and £150k might be classified as ‘medium’. These levels should be appropriate to the size of the organisation, its appetite for risk and its current risk treatment framework. They should be approved by management, as part of their approval of the overall risk management framework.

While it is true that, in reality, there will be variations between the actual impact of different threat-vulnerability combinations, there is no value in calculating these variations precisely: the range within which the impact value of similar threat-vulnerability combinations might fall is such that the same control decisions are likely to be made in respect of each. A qualitative methodology, which enables you to look at similar risk levels as though they were the same, is cost-effective and produces comparable and reproducible results.

You should note that, although you are using monetary values to make the boundary levels comprehensible to assessors, the reason for this is to ensure that they are able to produce comparable results, rather than to apply a quantitative methodology, which this is not.

Your risk assessment approach should, therefore, ask you to input impact values separately for each of confidentiality, integrity and availability. More than that, it should follow BS7799-3 and or ISO27005 and the methodology we outline here. Use impact values as the asset values.

The starting point in asset impact assessment is to identify the ‘owner’ (as described in ISO/IEC 27001:2005, 4.2.1 – d1 footnote), the person who decides how the asset is used, by whom and for what purpose. The owner is best placed to explain and evaluate the damage done to the organisation if the asset’s confidentiality, integrity or availability is compromised. The asset owner should consider what business processes the asset supports, as well as the legal and contractual requirements in terms of the asset, and derive from these the value of the asset in terms of the cost to the organisation of compromise to each of the asset’s three information security attributes: confidentiality, integrity and availability.

When valuing each asset, the key question is: What value does this attribute of this asset have to the organisation and what would it cost us if it were compromised? The fixed asset register valuation and the financial cost of replacement are at best likely to be minor contributors to this exercise, which is far more based on a qualitative assessment of value.

The scale of this exercise is substantial. It is extremely difficult to carry out manually, requiring an excessive commitment of resources. It may also involve an assessment methodology that contains a high level of subjectivity, as a result of which the methodology is likely to fall foul of the ‘comparable and reproducible’ requirement. The only way that the risk assessment can be done cost-effectively, in terms of resource deployment and process accuracy, is by using an appropriate risk assessment tool.

The asset valuation table

We’ve said that the organisation would find an asset valuation table useful to guide risk assessors in assigning values to information assets within the scope of the ISMS. We have already seen that the risk assessment needs to produce reproducible and comparable results, and consistency in asset valuation is essential to this.

We also summed up current guidance on the approach to asset valuation by pointing to BS7799-3 guidance which says that assets should be valued to take ‘account of the identified legal and business requirements and the impacts resulting from a loss of confidentiality, integrity and availability’ (clause 5.1) and that ‘one way to express asset values is to use the business impacts that unwanted incidents, such as disclosure, modification, non-availability and/or destruction, would have to the asset and the related business interests that would be directly or indirectly damaged’ (clause 5.4). Clearly, the asset value is not the original cost of acquisition, nor is it the cost of replacement – although these aspects should be included in the impact valuation.

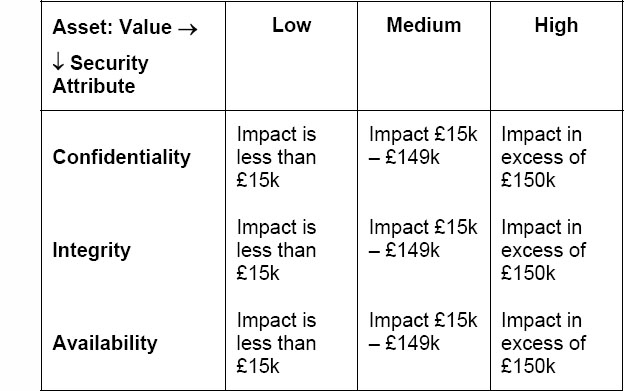

In a qualitative methodology, we need an appropriate asset valuation scale to support this process. You could use the following table:

Figure 10: Asset valuation table

In this table, the impact in each instance is the total cost of impact, including reputation damage, which itself is briefly discussed later in this chapter.

The impact evaluation should include, as part of this total cost of loss:

• monetary loss;

• productivity loss (which relates to the role of the asset in business processes);

• loss of customer confidence; and

• reputation damage.

It also needs to take into account:

• objective(s) of process(es);

• criticality of process(es) to the business and business objectives; and

• information sensitivity.

Business, legal and contractual impact values

In your risk assessment methodology, it is permissible to use, as the impact value, the highest of confidentiality, integrity and availability values, or a sum of them, or to carry out the assessment separately for each attribute of each asset. The third is usually the most sensible approach to pursue, as many controls are designed to deal with security issues around one – but not all – of the three information security attributes.

You should also remember that ISO27001 requires the risk assessment to take into account the business, legal or regulatory and contractual requirements for information security; it is entirely possible that, in respect of an individual asset, there will be different requirements and, therefore, different values in each of these areas.

For instance, a police force must keep personal data confidential so that it can comply with the Data Protection Act, but it may also need to ensure that the information is available to other police forces investigating a crime (business need). A healthcare provider will have a contractual responsibility to keep patient information confidential, a business requirement to maintain the integrity of that information (for instance, keeping the medical history up to date) and a compliance requirement to protect that data from exposure. The potential impacts of a breach of security in each of these areas could be different.

You, therefore, have to consider how the information is actually used in the organisation – in other words, in the context of the business, legal and regulatory and contractual requirements for information security – before you can really make an informed decision about the most appropriate approach to pursue.

This means that, for every information asset, you will have three contexts in which to carry out a risk assessment – business, legal/regulatory and contractual. In each context, you will need to assess impacts to confidentiality, integrity and availability. There are, potentially, therefore, nine assessments to make in respect of each asset. It is likely, for every asset, that one or more of these nine attributes will have little or no value, and that the impact in relation to one will be the same as in relation to another. While these are all acceptable inputs to the risk assessment, it will still be logical to start with this detailed approach. In any case, your methodology must be sufficiently practical to actually work, and a fully ISO27001-compliant risk assessment tool should automate and simplify risk assessments being made for each information security attribute for each of business, legal and contractual requirements.

Reputation damage

Reputation damage – a major concern of boardrooms and shareholders – is likely to be an impact of most breaches of information security. It can, however, be very hard to incorporate into a risk assessment process where the results need to be ‘comparable and reproducible’.

Again, the solution for this challenge can be as simple or as complicated as you want to make it. We recommend using one of the two following approaches:

Direct description approach

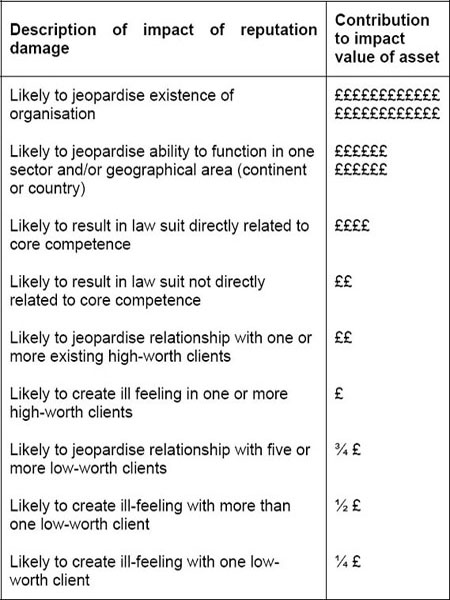

The direct approach is one where the asset owners use an agreed customisation of the table which follows (Figure 11), to determine the contribution that reputation damage would have on the impact value for that (attribute or component of that) asset for risk assessment purposes.

Coverage approach

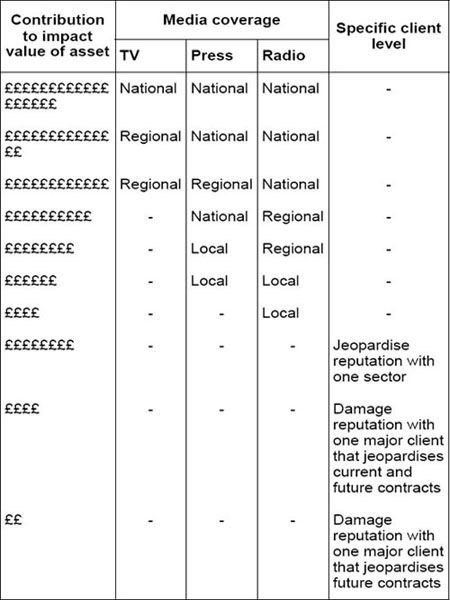

An alternative approach, in which the contribution of reputation damage to the value of the asset is estimated in light of the adverse coverage that might result, could use a customised version of the table on page 134 (Figure 12).

Each entry in the level of impact column would be given a value and this would be used in helping to determine which impact band in Figure 10 the value of the asset falls into.

Of course, those organisations that do not have a reputation to protect will not need to factor in this aspect of impact; for those that do, the input of the organisation’s PR advisers may be particularly useful.

Figure 11: Direct impact of reputation damage

Figure 12: Coverage impact of reputation damage