CHAPTER 2: RISK ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGIES

In this book we use the terms ‘method’ and ‘methodology’ interchangeably. A method is (as most standard dictionaries explain) simply a ‘way of doing something’. A method, in other words, will contain principles and procedures, describing both what must be done and how it must be done. A risk assessment methodology, therefore, is a description of the principles and procedures (preferably documented) that describe how information security risks should be assessed and evaluated.

An effective, defined, ISO27001 information security risk assessment methodology should meet the requirements of ISO27001 and, in doing so, should provide the organisation (particularly its board and management) with an assurance that all the relevant risks have been factored into the process, and that there is a commonly defined and understood means of communicating and acting on the results of that risk assessment. This does, of course, also mean that there will be a wider and better understanding, across the organisation, of the risks that are being dealt with, and of the practical business support budget that will be required in order to implement the required controls.

We recognise that there are many established risk assessment methodologies. However, as we said earlier, an ISO27001 risk assessment has to contain, as a minimum, a specific set of steps and many currently recognised methodologies simply do not meet the requirements of ISO27001. This is because they do not contain the required steps, or because they do not address organisational risk, or even because they provide a primarily technology-focused information security risk assessment. We are not going to address those methodologies here.

Publicly available risk assessment standards

There are three standards that exist around ISO27001, and these are particularly useful and pertinent to the development of an ISO27001 risk assessment methodology. The key standards that we refer to here are:

• ISO27002

• ISO27005.

• In the UK, BS7799-3:200619 (Information Security Management Systems – Part 3: Guidelines for information security risk management) is also available as guidance on the subject. As this book has an international audience, we will draw primarily on ISO27005, and will take additional input from BS7799-3:2006 where appropriate.

NIST SP 800-30 (Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems) was published in July 2002 and is still current. Like ISO27005 and BS7799-3, it is a code of practice, not a specification. It provides guidance that is consistent with the requirements of ISO27001 and we have, therefore, drawn on the NIST document wherever it provides additional, useful guidance.

ISO27002, the international code of information security best practice, identifies three sources for establishing an organisation’s information security requirements: the risks that the organisation faces; the risks arising from the compliance and contractual requirements imposed on the organisation in each of the jurisdictions in which it operates; and the ‘particular set of principles, objectives and business requirements for information processing that an organization has developed to support its operations’, which should largely fall out of the IT architecture the organisation has established.

Clause 4.2.1 – c of ISO27001 (Define a systematic approach to risk assessment) says an appropriate risk assessment, suited to the ISMS, and to the identified business, legal and regulatory requirements, shall be undertaken. The steps in the risk assessment process are, as we shall see, to identify: the information assets (i.e. anything that has value to the organisation) within the scope of the ISMS, owners for those assets, the threats to the assets, the vulnerabilities that might be exploited by those threats and the impacts that losses of confidentiality, integrity and availability may have on the assets, hence determining the degree of risk. While the risk assessment steps are mandatory, we still have to define a methodology for assessing risk and, for help in that, we will turn again to ISO27002 and ISO27005.

ISO27002 provides substantial guidance on risk assessment, but no detailed guidance on how the assessment is to be conducted, because every organisation is encouraged to choose that approach which is most applicable for its industry, complexity and risk environment. In its introduction, ISO27002 describes risk assessment in terms compatible with our introduction to it and also refers the reader looking for more guidance to ISO13335-3, which contains examples of risk assessment methodologies. ISO13335-3 has been withdrawn and replaced by ISO27005.

ISO27005 (Annex E) identifies only two possible approaches to risk assessment. These are:

• carry out an initial high-level assessment of the information assets to identify and prioritise treatment of those assets that have the most exposure, and implementing controls that relate to the most critical risks;

• conduct a detailed, formal risk assessment, using a formal methodology.

Either of these approaches would work for an ISO27001 ISMS; the critical thing is to think through the strategic implications of starting with a high-level risk assessment and identify how and when you move, in due course, to a detailed exercise.

ISO27001 and ISO27002 variously adopt (from ISO Guide 73:2002) definitions of risk, risk analysis, risk assessment, risk evaluation, risk management and risk treatment. We recommend that these definitions are, for the sake of consistency, adopted by any organisation tackling risk management and, as indicated at the outset, this book will proceed on that basis.

BS7799-3:2006 is another guidance document that describes different approaches to an information security risk assessment, and this could also be consulted when determining the methodology for an organisation.

ISO27002 is clear, in its introduction, that risk assessment is a ‘systematic study of assets, threats, vulnerabilities and impacts to assess the probability and consequences of risks’ or, in our terms, the systematic and methodical consideration of:

a) the business harm likely to result from a range of business failures; and

b) the realistic likelihood of such failures occurring.

The inclusion of this issue in ISO27002 clause 4, dealing with risk assessments, indicates its importance and the expectation that every control decision that an organisation makes will explicitly reflect a risk assessment. This clause was not in previous editions of the standard.

The risk assessment must be a formal process. In other words, the process must be planned and the input data, its analysis and the results should all be recorded. ‘Formal’ does not mean that risk assessment tools must be used, although, in most situations, they will improve the process and add significant value; in many organisations, it will not in fact be possible to carry out a risk assessment without using an appropriate tool. (We provide information on risk assessment tools later in this book.) The complexity of the risk assessment will depend on the complexity of the organisation and of the risks under review, and in particular, the approach to grouping assets. The techniques employed to carry it out should be consistent with this complexity and the level of assurance required by the board.

Risk is a function of likelihood and impact. The risk equation, to which we will return again and again, is:

Risk = Likelihood x Impact

This equation can be expanded to recognise that vulnerabilities are the exposure or weakness that a threat can exploit to compromise an asset and that, by ‘likelihood’, we simply mean the likelihood of the threat exploiting the vulnerability; and, adopting the principle that the impact value is the full consequence of an asset being compromised (as will be discussed in Chapter 10) we can restate the equation thus:

Risk = (probability of threat exploiting vulnerability) x (total impact cost of asset being exploited)

Our risk assessment methodology needs to equip us to ascribe values to these factors in the risk equation. While there are many different approaches, they essentially break down into two: qualitative and quantitative.

Qualitative versus quantitative

In conducting the impact analysis, consideration should be given to the advantages and disadvantages of quantitative versus qualitative assessments. A quantitative methodology is one that uses (primarily) quantitative input, i.e. mathematical data, and a qualitative one uses primarily non-mathematical input.

The main advantage of the qualitative impact analysis is that it prioritises the risks and identifies areas for immediate improvement in addressing the vulnerabilities. The disadvantage of the qualitative analysis is that it does not provide specific quantifiable measurements of the magnitude of the impacts, thus making a cost-benefit analysis of any recommended controls difficult to calculate precisely.

The major advantage of a quantitative impact analysis is, therefore, that it provides a measurement of the magnitude of some (but not all) impacts which can be used in the cost-benefit analysis of recommended controls. We say ‘but not all’ because there are some impacts (loss of reputation, loss of credibility, loss of public confidence, etc.) that are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to quantify meaningfully. At best, one may only be able to apply qualitative measures, such as ‘high’ or ‘very high’, without even being able to quantify the meaning of the term.

The further disadvantage of quantitative methodologies is that, depending on the numerical ranges used to describe the impacts, the meaning of the quantitative impact analysis may be unclear, as a result of which the result would have to be interpreted in a qualitative manner.

Quantitative risk analysis

This approach looks at two figures: one for the probability of an event occurring and the other the likely loss should it occur. A single figure is produced from these two elements, by simply multiplying the potential loss (measured in monetary terms) by its probability (measured as a percentage or fraction of times per year, say). This is sometimes called the annual loss expectancy (ALE) or the estimated annual cost (EAC). Clearly, the higher the number that an event or risk has, the more serious it is for the organisation. It is then possible to rank risks in order of magnitude (ALE) and to make decisions based upon this.

The problem with this type of risk analysis is that so long can be taken in producing a figure, and then revisiting the figures in light of comparison with other assets, threats and vulnerabilities, that no progress toward actual implementation of the ISMS is made. In some cases, this approach can promote or reflect complacency about the real significance of particular risks. The monetary value of the potential loss is also often subjectively assessed (i.e. it uses qualitative data) and, when the two components are multiplied together, the answer is equally subjective. A methodology which produces results that are largely dependent on subjective individual decisions, which are unlikely to be similar to the decisions of another person, is not one which will produce results that are reproducible and comparable and it will, therefore, fail the requirements of ISO27001.

In addition, controls and countermeasures often have to tackle a number of potential events and the events themselves are frequently interrelated. A detailed ranking in order of ALE can make it difficult to identify these interrelationships and can lead to poor decisions about controls; this approach is not, therefore, recommended.

Nevertheless, we recognise that a number of organisations have successfully adopted quantitative risk analysis.

Qualitative risk analysis – the ISO27001 approach

ISO27002 provides guidance that the risk assessment methodology should enable the organisation to ‘estimate’ the magnitude of security risks and use this information to make decisions about ‘proportionate’ security controls. ‘Estimation’ and ‘proportionate’ are two principles that form the basis of a qualitative risk assessment methodology, one that doesn’t need a precisely calculated ALE. A qualitative methodology ranks identified risks in relation to one another, using a qualitative or hierarchical scale (such as: very serious – serious – bearable – not a problem). It is, therefore, based on similar qualitative hierarchies, or scales, of threat and vulnerability seriousness, and of likelihood and impact.

One of the key concepts for risk assessment is contained in the BS7799-3 guidance that says that assets should be valued to take ‘account of the identified legal and business requirements and the impacts resulting from a loss of confidentiality, integrity and availability’ (clause 5.1). It also says that ‘one way to express asset values is to use the business impacts that unwanted incidents, such as disclosure, modification, non-availability and/or destruction, would have to the asset and the related business interests that would be directly or indirectly damaged’ (clause 5.4).

Finally, states BS7799-3, impact ‘values should be identified that express the potential business impacts if the confidentiality, integrity or availability, or any other important property of the asset is damaged’ (clause 5.4). It suggests that a standard asset valuation scale should be defined for assets to assist asset owners in correctly valuing their assets.

ISO27005 is less clear on this subject; it talks (as 8.2.1.6) about ‘identification of consequences’; it defines a consequence as ‘loss of effectiveness, adverse operating conditions, loss of business, reputation, damage, etc.’ and says that, in the risk assessment process, the ‘consequences that losses of confidentiality, integrity and availability may have on the assets should be identified.’ Impact and consequences are really different words for much the same concept, which is to establish the level of damage the organisation will suffer as a result of any given security breach?

A qualitative methodology is by far the most widely used approach to risk analysis and it meets the requirements of clause 4.2.1 – d (Identify the risks) of ISO27001. The risk level is based on banding values or levels for likelihood and impact, so that exact calculations are not required. ISO27005 says that a qualitative methodology ‘uses a scale of qualifying attributes to describe the magnitude of potential consequences (e.g. low, medium, high).’20 However, in order to ensure that the results are comparable and reproducible, the bands must be defined so that a medium impact in the judgement of one person can be demonstrated as comparable to a medium impact in another’s. The output of the risk equation would then also be qualitative.

A five-level risk scale, for instance, might lead to risks being placed on a scale that identifies them as:

|

Risk level |

Risk treatment action required |

|

Very high |

Unacceptable: action needs to be taken immediately. |

|

High |

Unacceptable: action to be taken as soon as possible. |

|

Medium |

Action required and to be taken within a reasonable timescale. |

|

Low |

Acceptable: no action required as a result of risk assessment. Any action should be the subject of a full cost-benefit analysis. |

|

Very low: |

Acceptable: no action required. |

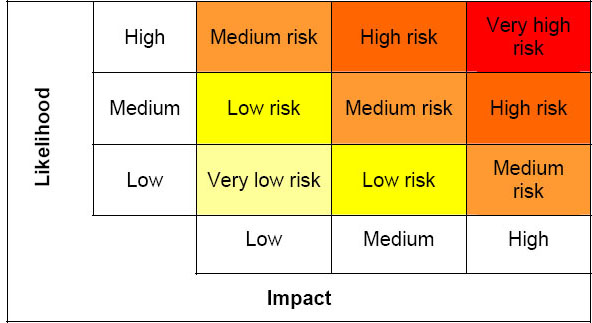

The output of the risk equation can be represented using a scale, such as the three-level likelihood and impact version below (which produces a five-level risk scale), and which relates the identified impact of an event occurring to an assessed likelihood of it actually happening.

Figure 3: Three-level risk matrix

The methodology recommended by this book, and developed fully in Chapter 7, is a qualitative one. Working methods for assessing impact, likelihood, threat and vulnerability are all important to the qualitative methodology, and the balance of this chapter will review the key concepts for each of these before we turn, in the next chapter, to their application in an ISO27001 risk assessment.

One of the key, practical benefits of a qualitative risk assessment methodology is that it recognises that there is inevitably a subjective aspect to any risk assessment exercise, and it provides a framework in which such assessments can give comparable and reproducible results. It also allows you to complete the initial risk assessment within a reasonable time period, and accepts that, in assessing and controlling risk, it is preferable to be ‘approximately correct, rather than precisely wrong’.

Other risk assessment methodologies

CRAMM

The CCTA21 Risk Analysis and Management Method (CRAMM) originated in 1985. Release version 5.1 became available in 2005. It follows three stages:

• asset identification and valuation;

• threat and vulnerability assessment;

• countermeasure selection and recommendation.

It applies a qualitative risk assessment methodology at an individual asset level, and it values assets primarily in relation to the impact that would be experienced by a breach in confidentiality, integrity and availability. The CRAMM methodology is in line with the requirements of ISO27001, although the methodology now is primarily implemented through the use of CRAMM tools. There is a description of the CRAMM tools in Chapter 5.

OCTAVE

One well-known approach that can be tailored to meet the requirements of ISO27001 is OCTAVE and the approach provides useful input for any organisation developing its own practical approach. Note, though, that OCTAVE does not, on its own, meet the requirements of ISO27001.

The Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, and Vulnerability Evaluation set of criteria, or OCTAVE22, was developed by Carnegie Mellon University. It is a set of criteria that can be developed into many different methodologies, and can use either quantitative or qualitative approaches; as long as those methodologies adhere to the OCTAVE criteria, each is recognised as an OCTAVE-consistent method.

The OCTAVE criteria consist of a set of principles, attributes and outputs. These include the principle of self-direction (i.e. the risk assessment is resourced from within the organisation being assessed), using a multi-disciplinary team (an attribute), and that outputs will relate to three phases of assessment.

To apply OCTAVE, a small team from across the organisation works together to consider the security needs of the organisation whilst balancing operational risk, security practices and technology. This team is known as the Analysis Team.

OCTAVE factors all aspects of risk into decision-making. That is to say, it considers assets, threats, vulnerabilities and organisational impact and includes them in the process. OCTAVE requires the Analysis Team to follow a specific series of steps:

• identify information-related assets that are important to the organisation;

• focus risk analysis activities on those assets judged to be most critical;

• consider the relationships among critical assets, the threats to those assets, and vulnerabilities that can be exploited by the threats;

• evaluate risks in an operational context – considering how assets are used in the business and how those assets are at risk due to security threats; and

• create a practical protection strategy for organisational improvement as well as risk mitigation plans to reduce the risk to the organisation’s critical assets.

OCTAVE uses a three-phased approach to enable the Analysis Team to produce a comprehensive picture of the organisation’s information security needs:

• Phase 1: Build asset-based threat profiles – the Analysis Team determines which information-related assets are important to the organisation and identifies the arrangements (controls) that are currently in place to protect those assets. They identify the assets that are most important to the organisation and describe the security requirements for each critical asset. They then identify threats to each of these assets, creating a threat profile for that asset. ISO27001, in contrast, requires the involvement of individual asset owners, and expects that all assets – not simply the most critical – will be included.

• Phase 2: Identify infrastructure vulnerabilities – the Analysis Team examines network access paths, identifying classes of information technology components related to each critical asset, and then determines the extent to which each class of component is resistant to network attacks. ISO27001, by comparison, looks for all potential vulnerabilities, including physical ones, to be identified.

• Phase 3: Develop security strategy and plans – the Analysis Team identifies risks to the identified critical assets and decides what to do about them, creating mitigation plans to address the risks to the assets, based on the Phase 1 and 2 analyses.

Carnegie Mellon University has developed three methodologies using the OCTAVE criteria: the original Octave Method (which forms the basis of the Octave Body of Knowledge), for large and complex organisations or those which are split across a number of geographical locations; Octave-S for small organisations with between 20 and 80 people and which are not complex in structure; and Octave-Allegro, a more streamlined approach for information security assessment and assurance.

IRAM, SARA, SPRINT and FIRM

The Information Security Forum (ISF) is a private, members-only organisation with some 260 members worldwide. It has developed a set of methodologies and tools which are available only to its members; these include tools for carrying out information security risk assessments. These tools, which are not publicly available, are designed to be used complementarily, and are:

• IRAM: Information Risk Analysis Methodologies;

• SARA: Simple to Apply Risk Analysis, primarily aimed at risk in business-critical systems;

• SPRINT: Simplified Process for Risk Identification, primarily aimed at important – but not critical – systems;

• FIRM: Fundamental Information Risk Management.

The ISF toolset supports all the fundamental risk management phases, and has many components that can be useful in an ISO27001 risk assessment. However, its focus is on business systems, not on individual assets, and therefore, the ISF tools would need to be adapted for use in the ISO27001, asset-based risk assessment environment.

As they are not publicly available tools (they are only available for use by members of the ISF – about 260 large, global organisations), and therefore, not likely to be of use to the majority of organisations tackling information security risk assessments, we have not developed them further here.

Other methodologies

DRAM, the Delphi Risk Assessment Method, and FRAP, the Facilitated Risk Assessment Process, are another two risk assessment methodologies. There are many others. The ENISA lists some of the less widely-used methodologies: http://rm-inv.enisa.europa.eu/rm_ra_methods.html.

The purpose of this book is to provide you with the basis for a methodology that you can use to carry out a specific ISO27001-compliant risk assessment. There is, therefore, little value in an extensive survey and comparison of different methodologies.

19 In the UK, ISO/IEC 27001 is dual-numbered as BS7799-2, ISO/IEC 27002 is dual-numbered as BS7799-1 (they are exactly the same standards, with alternative names) and BS7799-3 fits neatly into that numbering sequence. BS7799-3, however, is not the same standard as ISO/IEC 27005.

20 ISO27005 – 8.2.2.1

21 Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency, a UK Government Agency.