CHAPTER 1: RISK MANAGEMENT9

‘Risk’, says NIST,10 is the ‘net negative impact of the exercise of a vulnerability, considering both the probability and the impact of occurrence’.11 ISO27001, the international information security standard, doesn’t define risk, although it does provide definitions for the whole range of risk-related activities. ISO/IEC 27000:2009 Information Security Management Systems – Overview and Vocabulary (ISO27000) defines risk in the same way as does ISO Guide 73:2002,12 which is that risk is the ‘combination of the probability of an event and its occurrence’.

The NIST definition of risk is in line with that used in ISO27000, and is the first indicator that a risk assessment that will meet the requirements of ISO27001 will also be in line with the NIST recommendations. ISO27005 defines information security risk as the ‘potential that a given threat will exploit vulnerabilities of an asset or group of assets and thereby cause harm to the organization’, and ISO27001 follows this definition.

All organisations face risks of one sort or another on a daily basis and ISO27001 expects that an organisation’s information security management policy will align with ‘the organization’s strategic risk management context’13. It is therefore appropriate to consider, briefly, the organisational risk management context.

Risk management: two phases

Risk management is the process that allows managers to balance the operational and economic costs of protective measures and achieve gains in mission capability by protecting the IT systems and data that support their organisation’s missions.14

Organisations develop and implement risk management strategies in order to reduce negative impacts and to provide a structured, consistent basis for making decisions around risk mitigation options. Risk management has two phases: risk assessment and risk treatment.

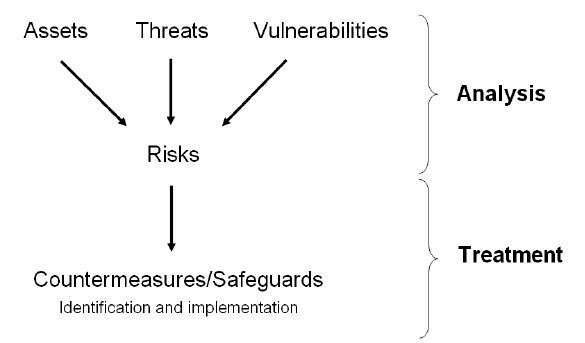

• Risk assessment is the process of identifying threats and assessing the likelihood of those threats exploiting some organisational vulnerability, as well as the potential impact of such an event occurring.

• Risk treatment is the process of responding to identified risks.

Risk assessment, also known as risk analysis, is the process by which risks are identified and assessed. The assessment process then stops. Any decisions and/or actions taken in light of the risk assessment are taken outside the risk assessment process, and are part of the risk treatment plan which, together with the risk assessment process, is the other constituent of risk management. Risk management is the superset of, and therefore includes, risk assessment.

Risk assessment/analysis and risk treatment are the two sub-processes of risk management

Figure 1: Risk management

While it is true to say that the risk management process starts with a risk assessment, it is helpful to have a broader understanding of the overall environment in which most risk management activity takes place.

Risk management, as we have said, includes both risk assessment (or analysis) and risk treatment, and is a discipline that exists to deal with non-speculative risks, those risks from which only a loss can occur. In other words, speculative risks, those from which either a profit or a loss can occur, are the subject of the organisation’s business strategy, whereas non-speculative risks, those risks which can reduce the value of the assets with which the organisation undertakes its speculative activity, are (usually) the subject of a risk management plan (in ISO27001, a ‘risk treatment plan’). These non-speculative risks are sometimes called permanent or ‘pure’ risks, in order to differentiate them from the crisis and speculative types.

Risk management plans usually have four, linked, objectives. These are to:

• eliminate risks;

• reduce those that can’t be eliminated to ‘acceptable’ levels; and then to either:

• live with them, exercising carefully the controls that keep them ‘acceptable’; or

• transfer them, by means of insurance, to some other organisation.

The following diagram illustrates the concept of ‘controlling’ risk. One only pays attention to those risks which have a likelihood of occurring and will have a negative impact. The greater the likelihood, or the more negative the impact, the greater the risk.

Controls, or risk mitigation, should be designed to reduce likelihood and/or impact such that the magnitude of the risk is reduced below a tolerance threshold. This tolerance threshold is also often known as the risk acceptance level.

Risk treatment plans reduce identified risks to the agreed risk acceptance level, here represented by the coloured area.

Figure 2: Risk treatment

Pure, permanent risks are usually identifiable in economic terms; they have a financially measurable potential impact upon the assets of the organisation. Risk management strategies are usually, therefore, based on an assessment of the economic benefits that the organisation can derive from an investment in a particular control or combination of controls. In other words, for every control that the organisation might implement, the calculation would be that the cost of implementation would be outweighed, preferably significantly, by the economic benefits that derive from, or economic losses that are avoided as a result of, its implementation.

The organisation should define its criteria for accepting risks (for example, it might say that it will accept any risk whose economic impact is less than the cost of controlling it) and for controlling risks (for example, it might say that any risk that has both a high likelihood and a high impact must be controlled to an identified level, or threshold). The enterprise risk management framework is, most usually, the framework within which organisations define their risk acceptance criteria in the light of their risk appetite and, as a result of which, define their systems of internal control.

Enterprise risk management

Enterprise risk management (ERM) is an increasingly important component of corporate governance and it provides an overall context for internal control activities.

Turnbull Guidance

The Turnbull Guidance15, within the UK’s Combined Code on Corporate Governance, is very clear on the steps that UK-listed companies should take in respect of risk: paragraph 19 of the Turnbull Guidance states that:

An internal control system encompasses the policies, processes, tasks, behaviours and other aspects of a company that, taken together:

• Facilitate its effective and efficient operation by enabling it to respond appropriately to significant business, operational, financial, compliance and other risks to achieving the company’s objectives. This includes the safeguarding of assets from inappropriate use or from loss or fraud and ensuring that liabilities are identified and managed;

• Help ensure the quality of internal and external reporting. This requires the maintenance of proper records and processes that generate a flow of timely, relevant and reliable information from within and outside the organisation;

• Help ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and also with internal policies with respect to the conduct of business.

Paragraph 20 recognises that ‘a company’s system of internal control … will include … information and communications processes’. Paragraph 12 is clear that ‘internal controls … should include all types of controls including those of an operational and compliance nature, as well as internal financial controls’.

Basel 2

Pillar 1 of the Basel 2 Accord aims to align a bank’s minimum capital requirements more closely to its actual risk of economic loss, aiming to establish an explicit capital charge for a ‘bank’s exposures to the risk of losses caused by failures in systems, processes, or staff or that are caused by external events’.16 Those banks whose approaches to measuring, managing and controlling their operational risk exposures are appropriate to the risk area will have lower capital requirements.

COSO

A widely respected ERM framework is the one developed by COSO,17 the body that was also responsible for developing the internal control framework that has been used in the vast majority of organisations to demonstrate compliance with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). The COSO ERM – Integrated Framework is in line with both Turnbull and Basel 2 when it defines ERM as:

… a process, effected by an entity’s board of directors, management and other personnel, applied in strategy setting and across the enterprise, designed to identify potential events that may affect the entity, and manage risks to be within its risk appetite, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of entity objectives.

This definition contains many of the attributes that are also relevant to information security risk management. ERM objectives include:

• aligning risk appetite and strategy;

• consistently applying risk treatment criteria (enhancing risk response decisions), with the options to: accept, reject, transfer, control;

• reducing operational surprises and losses;

• identifying and managing multiple and cross-enterprise risks;

• seizing opportunities – after considering a full range of potential events;

• enabling risk-related deployment of capital.

Organisations that already have an ERM framework of some description in place are at an advantage in taking forward the ISO27001 risk management process, which should be slotted seamlessly within that overarching corporate ERM framework. The ERM objectives and risk acceptance criteria should be carried through into the ISO27001 risk management process, which should contribute to providing the board and management with a greater depth and breadth of assurance that information risk is being managed within pre-approved guidelines.

A pre-existing ERM is not, though, a pre-requisite for the successful development and implementation of an ISO27001 ISMS. Organisations that do not already have in place such a framework will need, at the very least, to develop their approach to risk sufficiently to be able to ensure that their information security risk assessment is business-driven, and is structured, systematic and reproducible. Moreover, the risk assessment approach will have to take into account the organisation’s ‘business and legal or regulatory requirements, and contractual security obligations’18.

It is also not necessary to wait until the organisation develops a strategic approach to risk, or even an ERM framework. Information security management needs to be tackled more urgently than the timeframe that the development of an ERM framework will usually allow.

There are always issues of integration that have to be addressed when an ISO27001 risk assessment methodology is being developed within or alongside a broader, more strategic approach to risk management. For instance, definitions, roles and responsibilities could all be different, timeframes could be seriously out of alignment, and the ERM framework quite often tackles risk on a top-down basis, while ISO27001 requires a bottom-up approach to the identification and control of risk.

9 Some of this chapter replicates (but does not replace) material that is already in IT Governance: A Manager’s Guide to Data Security and ISO 27001/ISO 27002 (Kogan Page, 2008), as well as International IT Governance: an Executive Guide to ISO 27001/ISO 17799 (Kogan Page, 2006), and is repeated here to provide the top-level context for the further, more detailed, contents of this book. Readers are encouraged to read the original books for the full value of the overall guidance on planning and executing an ISO27001 project.

10 The National Institute of Standards and Technology is the US Federal Agency that develops and promotes measurement, standards and technology.

11 NIST SP 800-30.

12 ISO/IEC Guide 73:2002, Risk Management – Vocabulary – Guidelines for use in standards.

13 ISO27001, clause 4.2.1 – b3.

14 NIST SP 800-30, clause 2.1.

15 Revised Turnbull Guidance published October 2005, available for download from http://www.frc.org.uk/corporate/internalcontrol.cfm.

16 BIS Press Release, 26 June 2004.

17 The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (www.coso.org).

18 ISO27001, clause 4.2.1 – b2.