CHAPTER 11: LIKELIHOOD

Each of the preceding stages of the risk assessment has a relatively high degree of certainty about it. The vulnerabilities should be capable of technical, logical or physical identification. The way in which threats might exploit them should also be mechanically demonstrable. The decisions that have to be made are those that relate to the actions the organisation will take to counter those threats. Before that, however, there needs to be an assessment as to the likelihood of the event, and what the appropriate response to it will be. This means that the actual risks have now to be assessed and related to the organisation’s overall ‘risk appetite’ – that is, its willingness to take risks.

Risk analysis

ISO27001 (clause 4.2.1 – e) sets out the requirements in terms of analysing the risks. Until this point, the assessment has been carried out as though there was an equal likelihood of every identified threat actually happening. This is not really the case and this is, therefore, where there must be an assessment – for every identified impact – of the likelihood or probability of it actually occurring. ‘Likelihood’ in the risk equation is a value representing the probability of an identified threat exploiting a specific vulnerability in the asset.

Probabilities might range from ‘not very likely’ (e.g. major earthquake in Southern England destroying primary and backup facilities) to ‘almost daily’ (e.g. several hundred automated malware and hack attacks against the network). Again, a simple set of stepped, qualitative levels should be used.

The likelihood level should be estimated by considering the frequency at which the threat is likely to occur in the future and the probability of the threat exploiting and/or breaching the vulnerability when it does occur:

Likelihood = Frequency of threat occurring x Probability of vulnerability being breached

Most methodologies simply make, for each identified threat, a single assessment as to the likelihood of the threat occurring and exploiting the vulnerability, and then mapping that level directly to the estimated impact level in order to arrive at an assessed risk level.

Some methodologies insert an intermediate step, which involves a matrix that helps calculate the likelihood level by reference to the probability of both the threat occurring and the probability of it successfully exploiting the identified vulnerability.

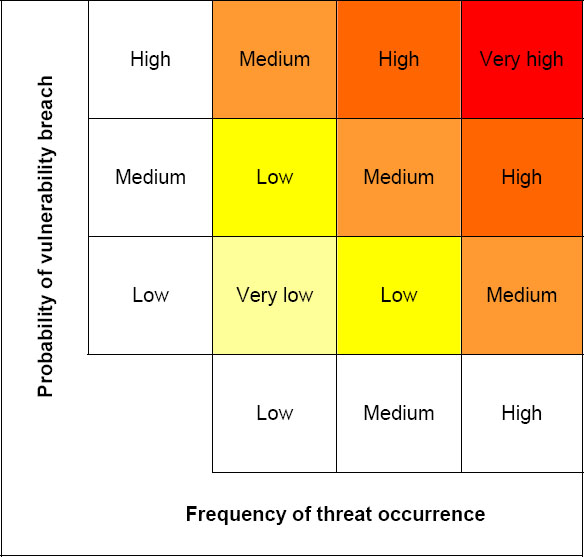

For example, an intermediate likelihood matrix constructed on that basis might look like the one in Figure 13, opposite.

In this example, using three-level scales for each of the vulnerability and threat frequency axes gives a five-level (very low – low – medium – high – very high) likelihood scale. Of course, the boundaries for each of the scales for the threat and vulnerability axes need to be defined so that the assessment results can be reproduced and will be comparable.

Figure 13: Likelihood matrix

Either approach is acceptable for the ISO27001 risk assessment. As long as the method for determination of likelihood is defined so that it can be estimated in a manner by which it is reproducible and comparable the process will satisfy the requirements of the standard. The decision as to whether or not there should be an intermediate step is one entirely for the organisation.

Information to support assessments

For the risk assessment methodology to provide ‘reproducible and comparable results’, there certainly needs to be some objective basis of guidance for assessing or estimating likelihood.

A key challenge is that, while risk assessment may draw substantially on historic records, risk management decisions are based primarily on assessments of the future. Whilst one can – and should – use history (and that means collecting, analysing and improving detailed monitoring statistics) in order to inform one’s assessment of the future, it is extremely important to bear in mind that ‘things change’ and the ‘thing’ that changes most for today’s organisations is the risk environment.

Just because a threat has never occurred to date does not mean that it never will. This may seem an obvious statement, but it is the implications of it that need to be kept in mind when conducting and reviewing risk assessments. The rate of change in technology alone is, for instance, a key source of risk for enterprises.

Historic data, facts and figures are all, nevertheless, going to be of enormous value in the risk management process. Historic figures about the risk environment (frequency and nature of threats, the cost of successful attacks, the costs of various mitigation measures, and so on) all inform the initial risk assessment, as well as the ongoing risk management process. As we shall see in due course, ISO27001 expects us to measure the effectiveness of the controls that we select and to use this information to feed the continuous improvement process.

There are a number of challenges in creating this data, including:

• defining a robust methodology, one that enables the process and outcome to be reproducible and comparable, for estimating costs, such as reputational damage, the inadvertent disclosure of confidential information, and disaster recovery costs;

• evaluating control implementation costs, and particularly their impact on productivity;

• the rate of change in threats, technology/vulnerabilities and control options/tools to address them; and

• ascribing values and likelihoods to potential future events, in an environment which is more likely to bring new threats than to repeat old ones.

It will be essential that the risk management process has built into it sub-processes for collecting relevant information about threats and activities undertaken and, particularly, about changes in the risk environment, so that management can use this information to improve and strengthen its information security management system.