5. The Coming Webby Store

The webby store, a store in which every display is visually managed just as an online web page, has been an increasing focus of my research for the past few years. Here I share a bit of the progress and describe where the convergence of online and bricks retailing is leading us. I always caution that as long as people are living in bricks-and-mortar houses, they will be shopping in bricks-and-mortar stores. But bricks retailing is quickly learning the advantages achieved by online shopping, within the four walls of their bricks stores. Buy-online-pick-up-in-store (BOPIS), or click-and-collect, is an example of this convergence and a natural response to the success of online retailers like Amazon. The webby store is the next logical advance that will lead bricks retailers to manage every display inside the store as if it were a web-page. Conceptually, it already is. (See Figure 5.1.)

We illustrate here that no matter whether the shopper is online or offline, the path to the sale is mostly through the eyes. Some details of this are measured and reported in my blog post “From Opportunity to Final Purchase.”1

On the left, we see the actual Amazon display of salty snacks, with one major adjustment to what is actually a fairly large web page if you scroll from top to bottom. But here we removed everything from the “shelf” except the packages on display—much like a comparable display in the supermarket. We discarded all the non-package printing and collapsed the product images into the remaining blank space. Notice that Amazon has a lot more products in a comparable space, and this is a direct consequence of the fact that their warehousing is elsewhere, whereas the bricks retailer does most of their warehousing on their own store shelves.

I have enlarged Amazon’s social marketing tool, the #1 Best Seller tag, as well as our own comparable Top Seller tag to make them more visible in the photos. On the actual Amazon web page, the two tags are actually far removed from one another with one near the top of the page and the other near the bottom, so the shopper doesn’t see them both at the same time. That’s a tip for the bricks retailer, too.

Now that you can see something of the foundation of a webby store, Figure 5.2 shows some early results for one of the several hundred displays in this store:

Figure 5.2 What the crowd of shoppers actually purchased (on the left); and the mathematically modeled attention and path of their eyes (on the right).

The bubbles on the left accurately reflect, by area, the sales of the actual item under the bubble. This lets you see at a glance, for single displays or whole aisles, what is moving and what is not. You’ll notice that the largest bubble falls onto a product called out by the Top Seller social marketing tag. Across the store, 80 such items enjoyed an average 40% lift compared to total store sales movement. This specific item enjoyed a 25% lift. It’s a lot easier to sell shoppers what they want to buy than what suppliers and retailers typically want to sell. In the tug-of-war between sellers and buyers, give up and come around to their side, and sell them what they most want to buy. What shoppers buy the most of—that’s what you can sell them even more of!

Your top product becomes your top product because it scratches an itch that the shopper has, and it does that better than any other of your products. The shopper is really number one, not you or your top seller.

Some marketers assume that whatever they are selling a lot of is approaching some limit. Was Robert Woodward wrong in 1923 when he set the goal for Coke that his product should be “always within an arm's reach of desire?”2 Forrest Mars promoted the same “arms reach” philosophy within his candy company. Don’t limit shoppers, your products, or yourself.

The eye track on the same display, illustrated on the right, shows you the density of the eye's focus. That is, a mathematically modeled representation of just how long the eye can be expected to stare at that exact point. The labels 1,2,3,4 show the modeled order in which the eye is expected to look at each item.

Notice that in this instance, the eye first looks at the bright red-orange package on the bottom shelf, then glances to the far right of the second shelf at the contrasting, distinctive blue package, and then to the third shelf at another orange package before ending back on the bottom shelf, where most purchases are made from this particular display. Notice the three intense areas of focus on the edge of the fourth shelf, where three different salsas are being offered. But the focus is mostly on the price tags, not on the product itself, possibly suggesting particular price sensitivity about these items. This representation does not totally represent the actual shelf, because the current modeling program uses a photograph rather than the actual shelf. We expect to improve this technology to conform distortions in the photo process to the real world of the store shelf.

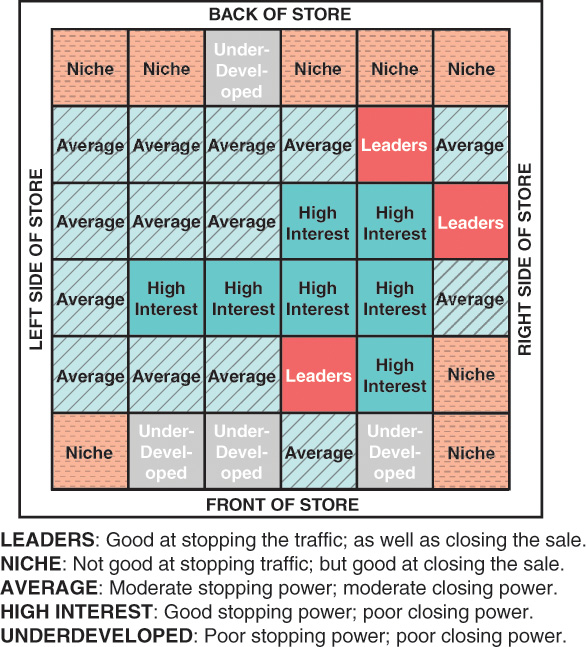

In some ways, this mathematical modeling of visual images parallels our own mathematical modeling of category performance across stores. The Atlas4 tool allows modeling of store layouts with rather detailed reports of performance of all of the categories, depending on the placement of categories of interest, as well as all the rest of the store. One derivative of this work is the discovery of the geographic impact of in-store location. We divided categories into five performance groups, listed at the bottom of Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 The geographic locations in a store have a major impact on how shoppers shop it. Same is true of location on a web page. (Suher, J and Sorensen, H (2010) The power of Atlas: why in-store shopping behavior matters, Journal of Advertising Research, 21, March, pp. 21–9.)

We are working toward a long-term goal of mathematically modeling all shopper behavior in stores, both their physical movement around stores, and what their eyes are doing while making those movements—ultimately leading them to make individual purchases.

All these detailed spatial metrics in bricks stores open the way for those stores to enjoy the same merchandising advantages as online stores have in managing their web pages. “Web” metrics of bricks displays can facilitate the same detail and flexibility that online retailers enjoy inside the four walls of the bricks store. However, more detailed visual metrics in the bricks store will return the favor to online operators. The total visual experience in bricks stores is often superior to the total online experience.

This development of metrics is not an academic interest. It is vitally important to move the efficiency/productivity of stores. Metrics can move performance—see the sidebar, “Charles Schwab Used the Suggestive Power of Metrics to Double Production.”

I always try to represent the best interest of the shopper. And that true interest, expressed through their behavior, is in acquiring their wants and needs more efficiently and conveniently. Whatever is done efficiently will be done in greater quantity. And the webby store is the ultimate in efficiency for the bricks store, just as a “bricky” website, one informed by bricks store learnings, may be the most efficient web store. What works best for the shopper is what works best for me and you.

As long as bricks-and-mortar retailers rely on the kind of operations and product-oriented reports that they have in order to survive and thrive, they will be sitting ducks for retailers with reports that give a picture of shopper behavior, reports which make obvious even to a stock clerk how to be more helpful to the shoppers in exactly the right way. Again, see the sidebar on Schwab’s use of a simple metric to effortlessly lead to massive production increases.

Just as I have spent years getting to this point, I don’t expect an entire transformation in a short time. But I do expect immediate increases in sales and profits for the retailer as a consequence of greater convenience (and efficiency) for the shopper. We’re putting the shopper in the driver’s seat to the benefit of all involved!

The “Ideal” Sized Store

Understanding the concept of the webby store, in which web services are the norm within the bricks store, gives us a glimpse into how retailers of the future might manage the Long Tail. Remember, Amazon is the “Everything Store.” Conceptually, there is no limit to the number of items in such a store. Just as the Industrial Revolution felled many barriers that once seemed natural at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Internet is currently shaping a world without the barriers we now consider unyielding.

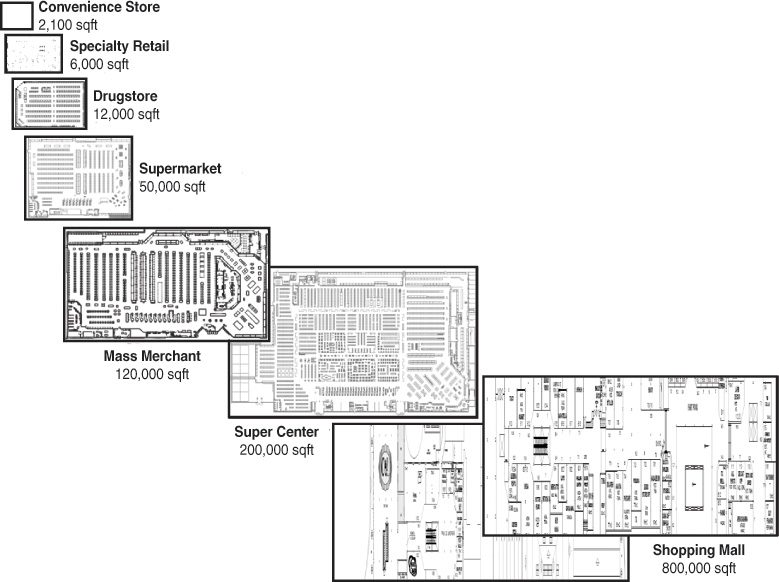

Here we use the scientific principles of human behavior and the potential role of technology in expanding and making that behavior more efficient and pleasant to assess how large a bricks store should be to most efficiently serve the shopping crowd. (See Figure 5.4.) Now, the retail industry is slowly embracing online selling techniques mostly as a pasting together of two distinct forms of retailing. (Further thoughts on this can be found in my blog post, “Retail ‘Spoons.’”5)

Figure 5.4 Married to an online engine served from a shelf device, the ideal size for a webby-bricks store is probably in the range of 10–20 thousand square feet: more stores, closer to the shoppers.

Apply this to the large spectrum of bricks retailing, illustrated here. Bear in mind, our science of shopping is built from studies across hundreds of stores, not just those illustrated here, but including electronics stores, building centers, auto parts stores, clothing stores, gift stores, and more.

This focus has led to the recognition that every supermarket is essentially a convenience store with a big long floppy tail. That is, regardless of your class of trade, your total range of merchandise, and whether the range is hundreds, thousands, or hundreds of thousands of items, the vast majority of your shoppers still leave the store with only a few items purchased, most likely in single digits, and rarely in the dozens. And the more of those items purchased, the less likely that those items will be needed in the next few hours or even days.

This means that even though the Long Tail is a powerful, attractive force bringing shoppers to the store, most of it can be served by pick-up or delivery later. Hence the assertion that every bricks store is a convenience store. However, the attractive property of the bricks store needs to be served by offering the entire online Long Tail from within the bricks store, not as a pasted-on addition.

Most thinking about online selling within bricks stores has settled on shoppers having a personal device, such as a smart phone, tablet, or the like, to actually bring the Long Tail within the store. This concept pits stores that rely on shoppers to BYOD (bring-your-own device) against stores that utilize the shelf edge not only to display prices but also to display—through the store’s own devices—a range of products beyond those available on the shelf. These devices can also facilitate the purchase of those items at the shelf, transforming the shelf from an immediate delivery device into a sales device that opens access to hundreds or thousands of additional products that might be picked up later on this shopping trip, delivered within hours to the home, or picked up at the same store on another convenient day. Now, we are talking about a real convenience store, servicing more than the gas-and-snacks model! However, this means that even a current-model convenience store might increase their offering from a few hundred items to millions.

Review Questions

1. What is a webby store and why should bricks self-service retailers consider utilizing this concept?

2. How are crowd social marketing and affinity marketing utilized in a webby store? What implications does this have for managing the Long Tail?

3. Ponder on the phrase “every supermarket is essentially a convenience store with a big long floppy tail.” What does this realization mean for grocery retail competition? Can online ordering, click-and-collect, and delivery services bring convenient stores closer to traditional supermarket formats?

4. Consider the paradox of the Long Tail—it—is a powerful force that attracts shoppers to the store, but the sheer volume of this “parked capital” can detract shoppers from getting what they need in a store. How can the Long Tail be managed in a convenience store and in a traditional supermarket?

2. http://businesscasestudies.co.uk/coca-cola-great-britain/within-an-arms-reach-of-desire/introduction.html#axzz3vwEnBRFR and https://www.youtube.com/user/3MVisualAttention

3. Carnegie, Dale (2010-08-24). How to Win Friends and Influence People (pp. 209–210). Simon & Schuster.

4. http://www.shopperscientist.com/atlas/ or Suher, J and Sorensen, H (2010). The power of Atlas: why in-store shopping behavior matters, Journal of Advertising Research, 21, March, pp. 21–9.