Chapter 6

Insight and Level 3: Collaborate

What does the meeting look like when someone is successful in selling me an idea? What happens is they run the conversation process so that, even though I might be expecting a selling pitch, it turns out to be a dialogue. They don’t just sell something to me; they work out something with me. At the end of an hour, I have the insight and want to run with an idea rather than feel like an idea is being imposed on me.

—Leonard Schlesinger, professor, Harvard Business School, and former chief operating officer, Limited Brands

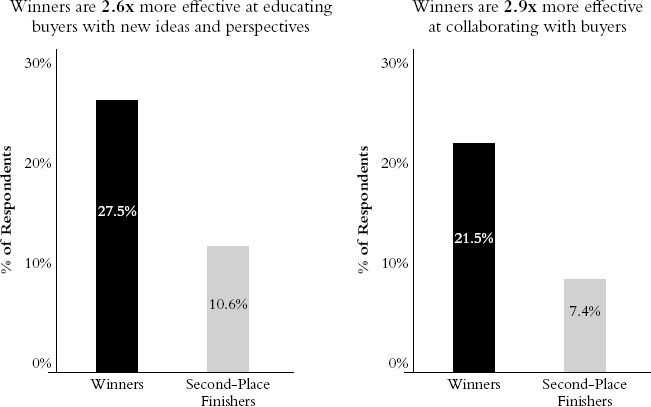

In our research, we found the top two factors that most separate sales winners from second-place finishers are (1) “educated me on new ideas and perspectives” and (2) “collaborated with me” (Figure 6.2). When sellers do these things, they aren’t just selling the value; they are the value.

Figure 6.2 Top Two Things Winners Do Differently: Educate and Collaborate

They are the value because they’re bringing insight in two ways:

- They bring new ideas directly to the table in the form of education.

- They interact with buyers in a manner such that they achieve insight on their own or with the seller as a team.

In the past several years, we’ve seen collaboration and education bubble up to the top as sales success factors in both our client work and in our other research efforts. In RAIN Group’s Benchmark Report on High Performance in Strategic Account Management,1 we studied what sets apart the companies with the greatest revenue, profit, and satisfaction growth in their strategic accounts from the rest of the pack.

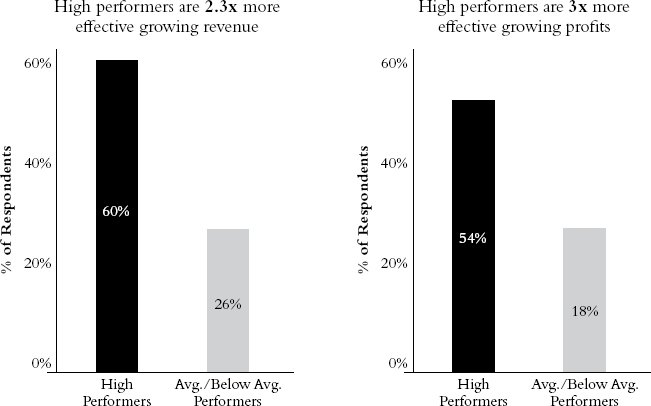

The high performers represented about 19 percent of our database of 373 companies studied. High performers grew revenue by 20 percent or more in their strategic accounts more than twice as often and grew profit by 20 percent or more three times more often than the rest of the companies. (Figure 6.3)

Figure 6.3 High Performers Compared with Average/Below Average Performers

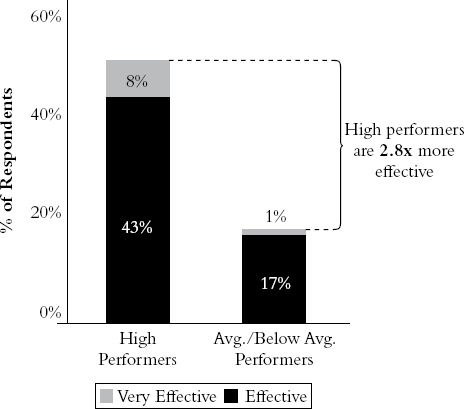

One of the most significant findings from this research is that these high-performing companies build collaboration with their buyers into their formal processes. Leaders at top-performing companies know that collaboration makes a difference and then make concerted efforts to ensure collaboration happens systematically (Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4 Process to Work Collaboratively with Accounts to Cocreate Value

Whether it’s part of the culture or sellers simply take it upon themselves to collaborate with buyers, the effect is the same: more sales wins and higher margins.

Power of Collaboration

Presentation versus Collaboration

Everyone likes intestinal meat, right? I mean, it’s so popular that it’s springing up on menu after menu in all the busiest restaurants, and kids are just begging for it.

Well, maybe not, but collaboration might just be able to make it happen. One of the founders of organization psychology, Kurt Lewin,2 set up a test with two groups of homemakers. His team lectured the first group about all the reasons for and benefits of eating intestinal meats. They also applied social pressure and played on the homemakers’ senses of patriotism (“You’ll help the war effort”) to persuade them. They even brought in others to talk about how much they loved intestinal meat and gave the homemakers recipes to try.

The second group participated in a facilitated discussion. Study leaders asked the homemakers about how they might persuade other homemakers to bring the benefits of intestinal meat to their families. They talked it out, role-played conversations, and shared ideas.

The results were astounding:

- Thirty-two percent of the collaborative discussion group went on to serve intestinal meat to their families at home.

- Three percent (!) of the first group did.

The collaborative process was 10 times more effective than the pitch-only persuasion. Although buying and selling have changed radically, some 70 years later, this particular part of human nature hasn’t.

Collaborate and involve, and you’ll get results.

Collaboration Is Unexpected

Buyers expect sellers to connect. Even though sellers don’t always succeed in connecting, the buyers expressed to us that they were surprised neither when sellers sought to understand their needs and craft compelling solutions to solve them nor when sellers were good listeners or likeable. Buyers expect sellers to convince. Buyers told us that they believed it was contingent on the sellers to make the case for why they should buy and why they should buy from them. They didn’t say all sellers were good at it, but buyers still expected the sellers to communicate the virtues of buying from them.

Buyers do not, however, expect sellers to collaborate. In fact, the more senior the decision maker we spoke to, the more often the decision makers expressed that they hope for—but rarely get—sellers they perceive to be collaborative with them and their teams.

Effects of Collaboration

When collaboration happens, sellers:

- Deepen relationships and trust. When the buyer and seller increase the frequency and depth of interactions, trust and relationship strength grows.

- Deepen understanding of need. When buyers and sellers collaborate, they get to know their respective businesses more intimately. Deeper knowledge replaces surface-level understanding of one another. The depth of interaction collaboration requires increases both the actual understanding of need and the buyer’s perception that the seller understands the need.

- Strengthen the quality and applicability of solutions. Collaboration increases the strength of the solutions, as deeper understanding of need leads to the most elegant solutions with the best fit.

- Spark insight and innovation. The act of collaboration itself sparks ideas and leads to innovation in how to achieve desired results in new ways.a

- Help buyers see the distinctions among sellers. Few sellers educate buyers with new ideas and perspectives. Few sellers collaborate, creating the platform for insight. When sellers do these things, buyers notice. Again, sellers don’t just sell the value. They become the value. This stands out.

- Build psychological ownership in buyers. The more sellers collaborate with buyers, the more the ownership of ideas shifts from seller to buyer. This increases buyers’ perception of the importance of action and urgency to act.

The first five of these points make sense on their face. The sixth and last point, however, is rarely discussed in selling circles, yet it has a tremendous impact on buying (and thus, of course, selling).

Psychological Ownership and Buying

Recall the opening story to this chapter from Len Schlesinger. Let’s assume the seller set a meeting with Schlesinger to introduce him to a new idea. At first, the idea belonged to the seller. By the time the meeting was over, the idea and the agenda for action belonged to Schlesinger.

Ownership of the idea shifted from seller to buyer. Not ownership in the sense of physical possession of a product, but psychological ownership, or the perception that something is the buyer’s.

The causes of psychological ownership are known to be the following3:

- Perception of control

- Depth of knowledge

- Self-investment

All three are outcomes of collaboration. When buyers are engaged in the shaping of insight and action, their sense of control grows. When they are deeply involved in an effort, their knowledge grows. The more they invest time and energy, the more they feel ownership of the opportunity. Collaboration is central to developing psychological ownership.

Psychological ownership is of critical importance in the two major phases of buying:

- Consideration: When sellers want buyers to consider an idea, they must get that idea on the buyer’s agenda for action. Once it goes on the agenda, ownership shifts from seller to buyer. (The higher up on the buyer’s to-do list it goes, the more powerfully the buyer feels the ownership.) Sellers who fail to transfer psychological ownership of a new idea do not make it past the buyer’s consideration phase.

- Selection: When there are competitors in the sale, it’s critically important for the seller to gain the buyer’s preference versus the other options. When buyers have a hand in defining the issues and crafting the solution itself, they feel most connected to it and advocate internally for that particular solution and vendor. It’s true as well that sales are sometimes lost not to competitors but to no decision. The more sellers involve buyers and the more buyers want to move the process forward, the more likely the sale is to happen.

Collaboration Is Powerful When Driving and Reacting to Demand

When the Seller Drives Demand

In the past 30 years or so, pitching has become frowned upon in many sales circles. Pitching features and benefits was central to selling through the 1970s but was replaced in the complex sale by a much heavier emphasis on questioning, listening, custom solution crafting, and a much lighter touch on advocacy of any kind.

However, as we described in the last chapter, sellers who win use the convincing story framework to introduce buyers to new ideas and opportunities. There’s nothing wrong with calling this a pitch. However, it’s not enough to simply pitch. (Anyone who knows about intestinal meat knows this.)

This is why the convincing story framework outlined in the previous chapter ends with an invitation to collaborate. The story can intrigue buyers and engage their minds, but engagement is simply the beginning of turning ideas into action.

The two keys to moving your opportunity up on buyers’ priority list are desire and ownership:

- Desire: They must want what you can do or produce for them.

- Ownership: You need to take something that wasn’t even on their radar screen and get them to believe deeply, “I need to do something about this!”

The convincing story starts the process of creating desire. Ownership (and increased desire) comes from collaboration.

When the Buyer Drives Demand

Even when buyers drive the demand, collaboration is equally effective. They may have already decided they want to climb a mountain (they own the agenda), but they often haven’t finalized the path to the summit (they don’t dictate the exact solution). They wait to learn from—and interact with—sellers. Recall that, according to the Information Technology Services Marketing Association, 70 percent of buyers want to involve sellers before they decide what to do and finalize a short list of options and providers.

Imagine for a moment a buyer is leading a process that will likely involve some kind of purchase. She checks in with three vendors. Two of them speak with her and then send a proposal. A third vendor educates her on different approaches and then designs the specifics collaboratively with her. Along the way, the seller asks questions about the buyer’s goals, vision, knowledge of possibilities, and so on. The seller also fills in gaps in buyer knowledge and offers opinions about what is likely to work best.

Even if the solutions are the same across sellers, who do you think the buyer will prefer?b

Sandy Wells, executive vice president of employer services at Bright Horizons Family Solutions, and her team routinely work with buyers for a 12- to 18-month period to help them define how their companies should set up early childhood education centers. She says:

We know that most of the projects we work on in the early stages are going to have to go to bid because of the size of the spend. If an RFP [request for proposal] arrives in-house that’s brand new to us, that’s a problem. It’s very important that we’re the ones educating the buyer before they get to the RFP process—we want to guide that process so it’s a project we can successfully implement and that will be a success for them.

We help them understand demand, space requirements, costs, and so on. We let them know what our competitors might say—for example, about the key financial drivers—and what our responses are. We give the buyers the chance to ask us lots of questions before we get to the formal RFP process, when it’s likely sellers will be blocked out of this kind of rich communication by procurement.

Tips for Collaborating across the Sales Process

Across all stages in the selling process, there are five common traits we see among sellers who collaborate the best.

- They prepare buyers to collaborate. Sellers should open the door for collaboration before meeting with buyers. For example, you can set a meeting with the stated premise of sharing some ideas you think may be worthwhile to a buyer at an existing account. But the ideas aren’t finished, and you need their help to think them through. This opens the door for their involvement in the process.

- Then kick meetings off with the right introduction and expectations, including asking them to dive in with thoughts and questions at any time. The idea is to invite buyers to become active participants in the process, not people who passively listen to pitches and then decide up or down on buying whatever a seller is selling.

- They ask the buyer for their thoughts and ideas. When sellers create their own opportunities, we know they often err on the side of overpitching and thus don’t create psychological ownership. Early on in discussions—even during a convincing story presentation—pause to ask buyers to share their thoughts. For example, you might say:

- Here is what happened at our other two client sites. Given what we have discussed so far, imagine for a minute you implemented something similar, and it’s six months from now. What effects do you think you might see? What would the impact be?

- You mentioned slow turnaround times and increasing production errors are huge issues. How does this affect the business? What would the impact be of increasing turnaround times and decreasing production errors?

- This is why we think it’s possible that you could increase revenue 20 percent if you make these changes in your marketing approach. We realize, however, that as much as most company leaders would want this kind of revenue increase, they’d be skeptical that it would actually happen. Why wouldn’t this work here? What would the roadblocks be?

- Some sellers ask, when they hear this last piece of advice, “Wouldn’t a question like this introduce barriers to the sale?” No. Odds are the company would want the improvements you say are possible, but buyers think the risks are too high. Get them talking about the roadblocks in their way, and you can address them. Allow roadblocks to remain hidden and skepticism to fester, and the sale dies. You just won’t know why.

- When buyers answer your questions, you can share stories of how the problems they envision have been solved at other places. You can also ask them, “Let’s look at that last roadblock. How could we fix that?” Many buyers talk themselves out of the problems as they ponder the solutions.

- They ask disruptive questions. Insight selling is a process that asks the buyer to think, pushes buyers out of their comfort zones, and gets to the heart of issues. As covered in Chapter 4, disruptive questions are essential to making this happen. If they can’t knock your tough questions out of the park, you help buyers see that the status quo isn’t good enough, that their thinking needs to change, and that action should be on the agenda.

- They shape the path forward together. Most of us don’t sell only one offering. Many sellers have flexibility in the service or product package, delivery, and mix they eventually design. When buyers have a hand in shaping the solution, psychological ownership and their commitment to seeing it come alive grow.

- You might say, “Given what we talked about, I think it would work well to do this here, but I think we have open questions about some of the details. You mentioned before that implementation might be a problem. What do you think we can do to make implementation really succeed?”

- The buyer might respond with, “Well, it’s a sticky one. In my experience, the best thing to do is . . .”

- They define parameters. Sellers shouldn’t, however, just ask the buyer how to move forward without defining parameters. “What do you think we should do from here?” is too open-ended. Buyers might not have a concept of what to do, and they might pick something that isn’t the best choice for them. It’s usually best if sellers provide a big-picture vision of what they think is the best path and then allow the buyer to shape it with them.

Facilitating Collaborative Group Discussions

Imagine a business meeting with several people sitting around a conference room table. People are talking, but the meeting isn’t really going anywhere. If the meeting ended at that moment, nothing would have been accomplished.

Suddenly someone grabs a marker, heads to the whiteboard, and starts asking questions: “Okay, let’s step back. First off, what are we trying to get done here? What do we know now? How do we know that? Why do we think that is happening? How have we approached this in the past? What is and isn’t working? How else could we get to where we want to be?” The meeting continues, now moving to a worthwhile outcome.

There is a name for this skillful wielder of the whiteboard marker: leader. He or she may not be in a formal leadership position, but a person who can guide a meeting down fruitful paths, get the best thinking from everyone, and inspire action has great influence and great value. When sellers do this—when they facilitate collaborative group discussions skillfully—they truly distinguish themselves. Unfortunately, many sellers do not do a good job leading facilitated discussions.

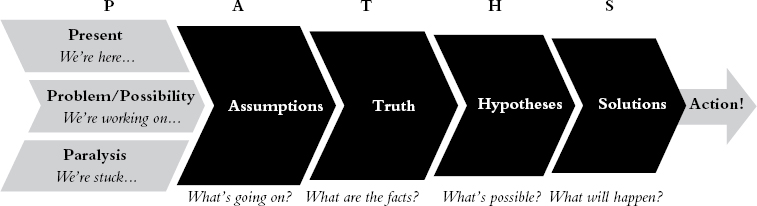

Sellers who win do a very good job in these types of meetings. Although there’s quite a bit written about meeting facilitation, little is geared toward sellers—the situations they face, the problems they solve. Thus, years ago we developed a simple framework that helps sellers and account managers lead successful facilitated sales meetings.

That framework is called PATHS to Action, and it looks like Figure 6.5.

Figure 6.5 PATHS to ActionSM

PATHS to Action outlines the five stages of a well-facilitated meeting. It’s comprehensive enough to cover all the bases in most sales situations, and it’s straightforward enough that sellers can apply it fairly quickly and successfully.

P—Premise: Present, Problem, Possibility, or Paralysis

P is the premise of the meeting. It’s the reason you’re all in the room together. The premise is usually one of the following:

- Let’s solve a problem.

- Let’s explore the virtues of a possibility.

- We’re stuck on something; let’s break the paralysis.

- Let’s get together to talk about the present, just to see where we are, and explore if we want to be somewhere else (and how can we get there).

At the beginning of your meeting, state the premise, and then make sure everyone agrees why they’re there and what they’re trying to do. This might seem like a minor point, but it’s not. Working to get the correct framing of the P may take as much as 10 percent of your scheduled meeting time. However, without getting this right at the outset, the rest of your time will be a wasted exercise.

A—Assumptions

The first discussion stage of a PATHS to Action meeting is to elicit assumptions from the group.

Asking broad, open-ended questions will get the meeting under way. There are numerous questions a meeting facilitator can ask to get everything out on the table. Here are just a few to get you started:

- What’s going on (regarding this particular topic)?

- What are the challenges in the way?

- Why are we working on this?

- Who are the important people in the process?

- What have we done in the past?

- If it hasn’t worked, why not?

- What could get in our way of implementation?

- What are people worried about?

- What are the risks we want to avoid?

- What has been holding us back?

- What does your gut tell you about this?

Whatever questions you use, the purpose of this stage is to get your arms around an issue fully, and (at this point) reserve making judgments on other people’s assertions. It’s quite all right if someone says, “I don’t agree with that.” At this point in the meeting, make certain you don’t fall into discussion about details. You will hash out what’s really true and what’s not in the next stage. Resist the temptation to dominate with your own assumptions. Be assertive but not overbearing. And resist the urge to solve the problem before you get the facts on the table (which will come in the next stage). Your goal before you move on is to get all the underlying beliefs, fears, and emotional blocks on the table. Later on you will decide what is true and what is conjecture or off base.

Note that even when people think they are done with assumptions, a disruptive question or two can open the floodgates to additional learning. For example, you might say, “I sense there’s an elephant in the room . . . something that people seem to want to say but are dancing around. Is there?” Of course, only ask this question if you sense key assumptions left unsaid, but if you do, ask away. Another question to ask to draw out the tougher-to-voice assumptions is, “If the most skeptical person in senior management were here in this conversation and wanted to throw in some roadblocks as to why we can’t get this done, what would this person say?” It’s surprising just how much more people will share when asked to play a role.

Remember, your role as facilitator is to get all the assumptions out on the table so that you can sift through them in the next stage.

T—Truths

Of course, not all assumptions will be facts. As you look at your list of assumptions, you will need to separate the facts and truths from the gut feelings, corporate myths, and personal prejudices. You will also want to filter out any unimportant distractions. Through this filtering process, you are left with the essential truths related to your P. Your goal at this point in PATHS is to end up with an elegant summary and synthesis of what’s truly happening.

As the facilitator, it’s your job to probe deeper on assumptions—are they indeed true? “Is this truly important for us to consider?” “How do you know that?” “Is there data to support this assumption?” You will also want to take care not to dismiss facts that are actually relevant or to confuse conventional wisdom with supportable facts.

When you seek the truth and you ferret out the important from the unimportant information, the 50 assumptions you listed on a whiteboard will get boiled down to 10 to 12 (or even fewer) important points. This consolidation is a necessary step to streamline what seems to be an overwhelming list of assumptions into a small and manageable subset of key truths.

You’ll often find that you have some unanswered questions about what is an assumption and what is a truth. When you get to this point, you will usually need to assign someone to do research to get the answers. PATHS to Action will often work in just one meeting, but sometimes it takes several meetings (if truths need to be verified and because some topics simply take longer to work through) to get to the right action.

H—Hypotheses

Once you have all the relevant and verified facts on the table, it’s time to examine possible actions and what will happen because of these actions. Because you are a seller, and not a disinterested facilitator, the meeting participants are likely to look to you to outline options. Certainly take a strong guiding hand in this stage, but make sure you collaborate with the buyers on what to do and how to proceed.

When you’re in this stage, take care not to simply list the possibilities. It’s not enough to say, “We could do this or this or that to solve our P.” You need to—in the true sense of the word hypothesis—put something forth for the sake of argument.

- “If we partner with marketing, we will increase quality leads and generate them faster.”

- “If we cold-call more, we will increase quality leads and generate them faster.”

- “If we outsource our lead generation, we will increase quality leads and generate them faster.”

Of course, all these hypotheses will be based on the truths you determined in the previous stage. At this point, your 10 truths will generally lead you to a whiteboard full of hypotheses, but a maximum of three to five will bubble up as most attractive.

S—Solutions

Once you have created your series of hypotheses that could possibly solve your P, you will want to review them and see which one or ones will have the greatest impact on the buyer and his or her P. Again, this may take one meeting or it may take several.

The challenge is helping the buyers avoid choosing solutions that get them only partway to their desired goal or do not get there at all. Rank your solutions to see which are most advisable, discussing the pluses and minuses of the various options. As you do, give the buyer the chance to own the thinking. Let’s say there are three solutions under consideration, but you know one of them doesn’t go far enough to get buyers the results they need.

You may need to step in and say, “This solution doesn’t have the horsepower you need. Here’s why.” It’s much more powerful, however, if someone on the buyers’ side jumps in and says it first.

Once you have agreement that a particular solution is the best PATH to solve the problem, move them beyond their present situation, or overcome any paralysis, you can develop the course of action that makes the solution a reality.

Finally, once you’ve decided a course of action, seek commitment, and then act.

Chapter Summary

Overview

- When a seller collaborates with the buyer, the seller becomes a key component of the value proposition.

- By facilitating collaborative meetings, you will gain stronger commitment—through psychological ownership—from the buyer to act on solutions you provide.

Key Takeaways

- To become a key component of the value, do what the sales winners do: educate buyers on new ideas and perspectives, and collaborate with them.

- To be collaborative in how you interact with buyers, do the following: Be responsive, be proactive, be easy to buy from, educate buyers with new ideas and perspectives, and collaborate with buyers to achieve mutually desirable goals.

- The collaborative process is more effective than pitch-only persuasion.

- When you collaborate with buyers, you will deepen relationships and trust, deepen understanding of need, strengthen the quality and applicability of solutions, spark insight and innovation, help buyers see the distinctions among sellers, and build psychological ownership in buyers.

- When the buyer has psychological ownership, it will help you succeed with the consideration and selection phases of the buying process.

- When the seller drives demand, the two keys to moving your opportunity up on a buyer’s priority list are desire and ownership. The convincing story starts the process, and collaboration continues the process by creating ownership (and increased desire).

- When the buyer drives the demand, collaboration is equally effective. Buyers may already own the agenda but often haven’t determined the exact solution. They learn from—and interact with—sellers.

- To successfully collaborate with buyers, prepare buyers to collaborate, ask the buyers for their thoughts and ideas, ask disruptive questions, shape the path forward together, and define parameters.

- Use the PATHS to Action framework to facilitate collaborative meetings with buyers:

- P—Premise: Present, Problem, Possibility, or Paralysis (The reason you’re all in the room together.)

- A—Assumptions (The first discussion stage of a PATHS to Action meeting is to elicit assumptions from the group.)

- T—Truths (As you look at your list of assumptions, separate the facts and truths from the gut feelings, corporate myths, and personal prejudices.)

- H—Hypotheses (Examine possible actions that may solve your P.)

- S—Solutions (Review possible solutions and see which one or ones will have the greatest impact.)