CHAPTER SIX

Measure the Effectiveness

We have looked at defining, designing, and developing the training program. Now we need to see if it does what we want it to do. This is another phase during which the course designer has less control—much as with the defining phase (Chapter 1). This is also when the instructor and the learners have the most accountability and when the training is most visible. Thus, this chapter focuses on the evaluation of training programs and their subsequent learner outcomes. Specifically, we review the critical importance of evaluation and the accomplishment of objectives—that is, whether job performance and organizational results have improved.

Formative and summative evaluations are discussed and compared, and the reasons for evaluation are identified. The process of evaluating a training program is outlined, and the outcomes used to evaluate that training are described in detail. Donald Kirkpatrick’s well-known training model incorporating the four major levels of evaluation is highlighted, as well as the five major categories of outcomes possible.

Another important issue—that of how good the designated outcomes are—is also discussed. Perhaps most important evaluation designs and the preservation of internal validity are reviewed, as well as calculations of the return on investment (ROI) for training dollars. In an environment of increased accountability, knowledge of how to show ROI is invaluable.

The Terminology of Training Effectiveness

Let’s begin by reviewing the definitions of some key terms and processes that pertain specifically to evaluation. You should have become familiar with these because of their use in earlier chapters of this book, but they particularly pertain here:

![]() Training effectiveness refers to the benefits that the company and the trainees experience as a result of training. Benefits for the trainees include acquiring new knowledge, learning new skills, and adopting new behaviors. Potential benefits for the company include increased sales, improved quality, and more satisfied customers.

Training effectiveness refers to the benefits that the company and the trainees experience as a result of training. Benefits for the trainees include acquiring new knowledge, learning new skills, and adopting new behaviors. Potential benefits for the company include increased sales, improved quality, and more satisfied customers.

![]() Training outcomes or criteria refer to measures that the trainer and the company use to evaluate the training.

Training outcomes or criteria refer to measures that the trainer and the company use to evaluate the training.

![]() Training evaluation refers to the collection of data pertaining to training outcomes, needed to determine if training objectives were met.

Training evaluation refers to the collection of data pertaining to training outcomes, needed to determine if training objectives were met.

![]() Evaluation design refers to the system from whom, what, when, and how information is collected, which will help determine the effectiveness of the training.

Evaluation design refers to the system from whom, what, when, and how information is collected, which will help determine the effectiveness of the training.

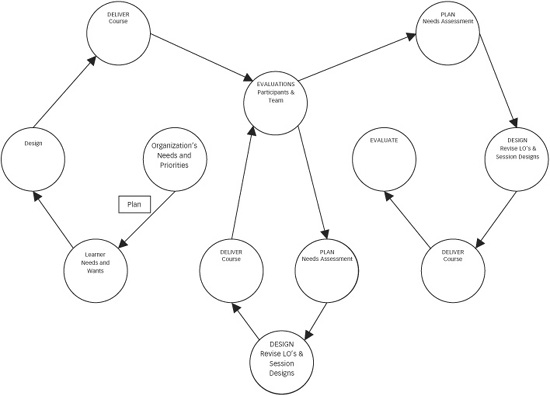

Because companies have made large dollar investments in training and education, and they view training as a strategy to be more successful, they expect the outcomes or benefits of the training to be measurable. Additionally, training evaluation provides a way of understanding the investments that training produces and provides the information necessary to improve training. Figure 6-1 shows the interlocking nature of training evaluation.

Figure 6-1. Interlocking nature of training evaluation.

The Evaluation of Training

We end this book as we began, discussing the success of a training program. From the start, all efforts to define a need for training, through design and implementation, were aimed at achieving measurable success. It’s time to review the process for determining that success. Ultimately, the evaluation leads to improvements in the program (content, instructional strategies, pace, or sequencing).

Thus, evaluation is a significant part of the design and development process. While we usually think of evaluation as something that takes place during or after the training, it really is critical to the entire process. And the heart of evaluation is the assignment of value and the making of critical judgments. The evaluation process measures what changes have resulted from the training, how much change has resulted, and how much value can be assigned to these changes.

The Levels of Evaluation

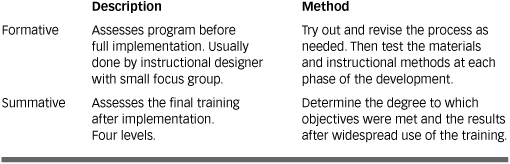

Because evaluation is so closely entwined with implementation, the methods of evaluation need to be built into the delivery of the training. There are two types of evaluation, as shown in Table 6-1—formative and summative. Each type provides different information to be sure that training is on track, and the table presents methods for obtaining that information.

Table 6-1. Two types of evaluation.

The formative evaluation assesses programs before their full implementation, usually by the instructional designers using a small focus group. This involves trying out and revising the training process along the way, testing the materials and instructional methods at each phase. The summative evaluation assesses the training after implementation, setting up the means to determine the degree to which learning objectives were met and how widespread the use was of the training.

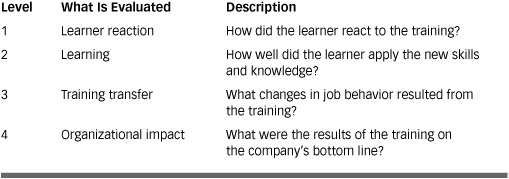

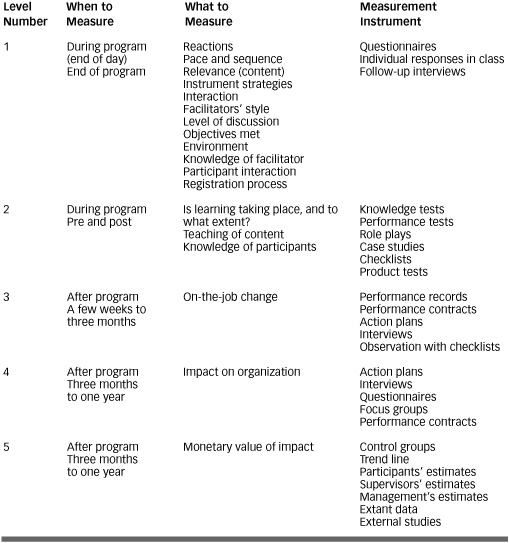

Within the summative evaluation are four levels, as introduced by Donald Kirkpatrick (1994) as a simple model, summarized and adapted in Table 6-2.1

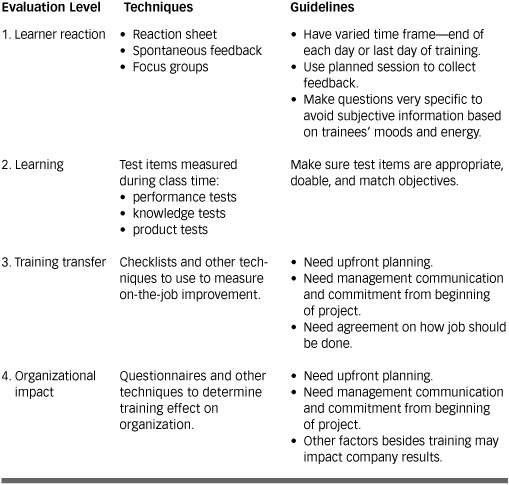

Based on these four levels, I present in Table 6-3 the evaluation techniques and guidelines for their use. Let’s look at each of these levels in turn.

Level 1: Learner Reaction

It’s easy to determine a learner’s individual reaction to the training. You can conduct an ongoing evaluation of the training during the sessions or after the sessions. Did the learner enjoy the session? Was the learner enthusiastic? Did the learner learn quickly and perform the task correctly? Although these questions call for subjective responses, it’s important that they are answered so you can determine if you did your job in building actions, developing skills, changing behaviors—and had an impact during the training program.

Table 6-2. Four-level Kirkpatrick evaluation process.

Table 6-3. Guidelines for evaluation techniques.

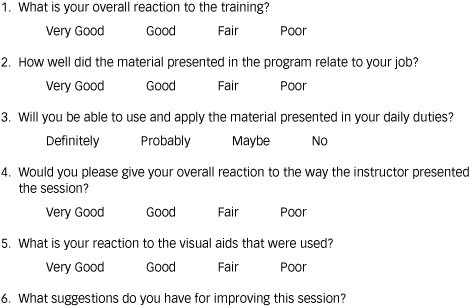

Measuring learners’ reactions to group sessions (conferences and lectures) is more difficult. However, if your plan is for training over a period of times you can check learner reaction as you go along so that you can improve future sessions, if necessary. Checking on the responses to group training is most often done via questionnaires. The results are compiled and form the basis for making modifications to the training program. Figure 6-2 is a sample questionnaire, with possible questions that yield the answers you want. Responses are commonly given on a numbered scale (0 = bad, 5 = good) or with fill-in spaces for writing comments.

Figure 6-2. Sample feedback questionnaire.

DIRECTIONS: Circle the appropriate response to questions 1–5 below, then use space provided to respond to question 6.

Level 1 evaluations measure participants’ feelings about the training, either ongoing or at the end of the course through participant feedback. The goal is to gather data that can be used in assessing training outcomes. Thus, each question posed usually deals with one aspect of the training at a time. Even when a rating scale is used, there should always be space at the end of the assessment for open-ended responses. Figure 6-3 is a sample of Level 1 evaluation questions with simple “agree” and “disagree” choices, but with space at the bottom for greater feedback.

Figure 6-3. Sample learner reaction questions.

DIRECTIONS: For questions 1 and 2, circle the word that best reflects your feelings regarding the training you have received. Then add any comments as a response to question 3.

1. The trainer’s instructions were easily understood.

Agree Disagree

2. The location of the training room was assessable to me.

Agree Disagree

3. What is the most beneficial information you received during the program?

Level 2: Learning

There are many ways to evaluate whether the learner has met the learning objectives. Level 2 evaluation can include both formal and informal strategies. Formal evaluation involves testing for that knowledge; informal evaluation uses the learners, peers, and course instructors to measure how well the objectives were met.

In essence, this level of assessment measures participants’ change over the duration of the training, so it is easy to anticipate the assessment during the design phase of the training program. Specifically, you use the statement of learning objective and outcome for each module to write an evaluation question. This question can then be given to the participants as a written exercise or used during a discussion as part of a review process. Remember, each question that you design should measure mastery of content. Don’t test to determine if a learner remembers everything; reserve testing for those points that are critical to job success. Test to see what the learner can apply directly to the job. Figure 6-4 shows two sample questions for this level of evaluation.

Figure 6-4. Sample learning questions.

1. Name the 5Ws that we discussed during this session, and when do you use them?

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

2. How do you define the term evaluation? What are the major components in your definition of the term evaluation?

But let’s take a closer look at each of these types of Level 2 evaluations:

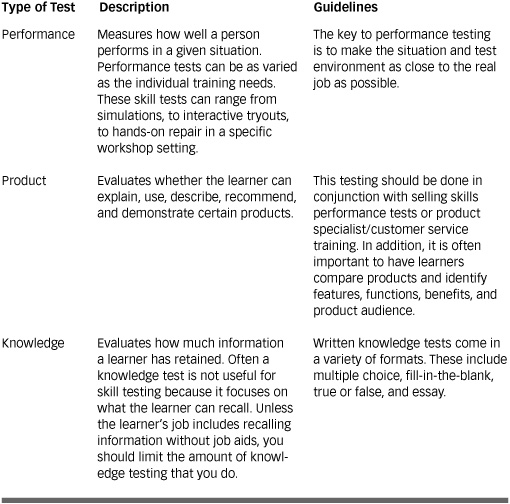

Formal Evaluations. Tests come in many forms. You select the type of test you want to use based on the nature of the training content, its critical nature, the training setting, and any corporate or federal guidelines regarding certification or licensing. Knowledge and skills testing is sometimes done prior to the training (to determine how much the learner knew before training) and then after the training to measure results. The difference in test scores indicates a gain as a result of the training provided. Table 6-4 shows three types of formal tests, with guidelines for their use.

Table 6-4. Three types of formal testing.

Many learners are uncomfortable with any type of testing, so it is important to set the stage before administering a test. Explain the purpose and use of the test, as well as the results, in a clear and timely manner. Take care to validate all tests to be sure they measure the appropriate skills and knowledge before they could be used for promotion or demotion. Table 6-5 offers some advantages and disadvantages for using these Level 2 evaluation strategies.

Informal Evaluations. Often, there is no formal testing, owing to the subject matter and noncritical nature of the content. But that does not mean that Level 2 evaluations are not used. Frequently, the learners will self-evaluate their learning or use their peers or classroom instructors to help measure their transfer of information.

Level 3: Training Transfer

This level of evaluation measures participants’ application of the newly learned information to the job. The way to measure whether the learners transfer their new skills or knowledge when back on the job is best evaluated through personal observation or testimony. Say, through supervisor or learner input, you heard how an employee performed previously (sloppy work habits); you can now compare those behaviors to the behaviors following the training (correct methods, clean work area). If behaviors have significantly changed, you can probably attribute that to the effect of training.

Some ways to measure Level 3 changes in behavior include follow-up surveys sent to participants after the training, on-the-job surveys, testimonials by peers or supervisors, and performance comparisons with untrained peers. Responses to these techniques are the feedback from participants who relate stories of their successes in applying the new concepts or, if the learners had signed a contract at the start of the program that promised they would apply the concepts, you have a date for checking back and a date for completion of the contract. Typical forms of evaluation for Level 3 include:

Table 6-5. Evaluation of learning guidelines.

![]() On-the-job surveys

On-the-job surveys

![]() Mystery customers/shoppers

Mystery customers/shoppers

Level 4: Organizational Impact

Evaluating the effect of training on the organization is the process of determining how much and how well the training led to increased organizational productivity or improved customer satisfaction, or how much it contributed to realizing the organization’s strategic business plan. When we use the term impact evaluation, we are usually referring to ROI. However, the term can mean other things as well, such as cost/benefit or intangibles. Essentially, the “results evaluation” examines the impact of training on learners’ work output.

There are two types of ROI for trainings, as shown in Table 6-6: forecasting ROI and cost–benefit analysis. The first is done prior to initiating a training program, to determine whether to go ahead with the plan; the second is done after implementation as a way of evaluating results.

Table 6-7 then considers the purpose of each of these evaluation levels in terms of what is measured, when, and with what instrument. Note that the table includes the fifth level of evaluation, the program’s monetary value to the organization. This table will prove valuable when you are trying to make decisions about what to measure and what tool to use.

Table 6-6. Evaluating the impact of training on organization.

Type of ROI | What It Means |

Forecasting ROI | Determines the desired results of a training so as to make a go/no-go decision before investing in the training. |

Cost/benefit analysis | Compares after-the-fact costs of training to after-the-fact benefits realized from training. |

Table 6-7. Purpose of the evaluation levels.

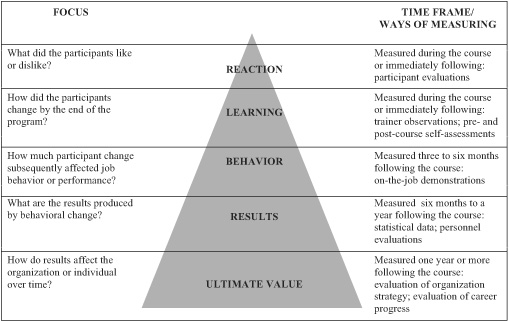

Evaluation’s Ultimate Value

The hierarchy of evaluation, shown in Figure 6-5, adds another level to the process: ultimate value. Presented as a pyramid, with ultimate value at its base, this system measures the outcomes and effectiveness of training, with its foundation being the affect of training on the organization over time.

This view of the assessment process provides a variable time line; it might take six months, a year, or even longer. You gather the data that reveal how the organization or individuals have been affected over time as a result of the training. Once you establish your data point, you can validate the change and establish that the change was a result of the training. Then, if possible, you can calculate the dollar value of revenue lost if the actions were not addressed and the changed behavior did not occur—this is a simple form of ROI. Figure 6-6 is a simple back-home exercise that you can provide your participants so they can record the transfer of training back on the job.

Figure 6-5. Hierarchy of evaluation.

Figure 6-6. Sample back-home exercise.

DIRECTIONS: Answer each of the following questions, based on your recent training experience.

1. Given the five levels of evaluation that you reviewed during your recent training, describe a situation in which you might be able to immediately integrate one of the levels of evaluation.

2. Write a short description of the situation:

3. Describe the suggested action you would take:

The Methods of Evaluation

There are many ways that you can assess training outcomes. Listed below are various techniques and short explanations on how to use the techniques in your training.

![]() Questionnaires. This is the most popular evaluation instrument that trainers use. Questionnaires can be a short reaction form or a detailed follow-up survey. In short, they can be used to obtain information at all levels of evaluation. For the questionnaire to elicit accurate data, however, the participants need to have good reading and writing skills.

Questionnaires. This is the most popular evaluation instrument that trainers use. Questionnaires can be a short reaction form or a detailed follow-up survey. In short, they can be used to obtain information at all levels of evaluation. For the questionnaire to elicit accurate data, however, the participants need to have good reading and writing skills.

There are two types of questions you can ask on a questionnaire: (1) open-ended questions, which give unlimited possibilities for responses; and (2) close-ended questions, which allow participants to select from predetermined choices.

![]() Surveys. This is a specific type of questionnaire, with several applications for measuring results at all levels. It can be used to gather information about perceptions, policies, procedures, work habits, and values. Note, however, that it is difficult to measure attitudes toward the training; that is better done though interviews or observations.

Surveys. This is a specific type of questionnaire, with several applications for measuring results at all levels. It can be used to gather information about perceptions, policies, procedures, work habits, and values. Note, however, that it is difficult to measure attitudes toward the training; that is better done though interviews or observations.

The survey is not a research tool per se. However, it can serve as a means of collecting data as part of a longitudinal study, or can be a quick check on participants’ responses to training with respect to materials, facilitation, and transfer back home.

![]() Tests. This form of evaluation may be best used to judge the effectiveness of skills-based training, not necessarily human relations training. Tests allow you to collect information on all levels of evaluation.

Tests. This form of evaluation may be best used to judge the effectiveness of skills-based training, not necessarily human relations training. Tests allow you to collect information on all levels of evaluation.

![]() Observations. This process can be used before, during, or after a training session to obtain information for all levels of evaluation. The desired behavior should be determined at the beginning of the training, with changes recorded. Observers should be trained in proper observation methods and be knowledgeable about their subject matter.

Observations. This process can be used before, during, or after a training session to obtain information for all levels of evaluation. The desired behavior should be determined at the beginning of the training, with changes recorded. Observers should be trained in proper observation methods and be knowledgeable about their subject matter.

![]() Interviews. This process can be time-consuming, yet it can yield valuable information that you would not get from surveys or questionnaires. Develop the interview questions before you conduct the interviews, and make sure you use the same questions for each interviewee.

Interviews. This process can be time-consuming, yet it can yield valuable information that you would not get from surveys or questionnaires. Develop the interview questions before you conduct the interviews, and make sure you use the same questions for each interviewee.

Types of Evaluation Data

Various types of statistics or data can lend credibility to your study. The following data sources can also serve as points around which to design and develop the training.

![]() Accident Rates. Statistics on on-the-job accidents can provide a frame of reference for developing your training. The only caution for using this information is to make sure that the statistics are accurate and that you use them appropriately. This information can be used to demonstrate why training is necessary.

Accident Rates. Statistics on on-the-job accidents can provide a frame of reference for developing your training. The only caution for using this information is to make sure that the statistics are accurate and that you use them appropriately. This information can be used to demonstrate why training is necessary.

![]() Quality Indicators. These are used in the evaluation process for both formative and summative assessments to determine if the training achieved the objectives and purpose of the course. That is, quality indicators are used to justify training. However, be mindful that the use is appropriate. If you do not have a baseline for the quality indicators, create one using industry standards, then develop your own organizational benchmarks for training.

Quality Indicators. These are used in the evaluation process for both formative and summative assessments to determine if the training achieved the objectives and purpose of the course. That is, quality indicators are used to justify training. However, be mindful that the use is appropriate. If you do not have a baseline for the quality indicators, create one using industry standards, then develop your own organizational benchmarks for training.

![]() Test and Retest Scores. Test scores can produce data backup to support your training, especially when the retest scores show marked improvement. You can use preliminary test scores to guide your training design and help establish training outcomes. Be careful to use tests appropriately, however; don’t test for topics or processes that do not require tests or outcome documentation.

Test and Retest Scores. Test scores can produce data backup to support your training, especially when the retest scores show marked improvement. You can use preliminary test scores to guide your training design and help establish training outcomes. Be careful to use tests appropriately, however; don’t test for topics or processes that do not require tests or outcome documentation.

![]() Pre- or Post-Training Data. Data that show improvement can serve as guidelines for learning and also for establishing learning goals. The pre- and post-training data should not be used inappropriately or serve as judgment of someone’s learning potential.

Pre- or Post-Training Data. Data that show improvement can serve as guidelines for learning and also for establishing learning goals. The pre- and post-training data should not be used inappropriately or serve as judgment of someone’s learning potential.

![]() Follow-Up Training. This is a popular strategy for ensuring that an ROI exists. Design your follow-up campaign to include the supervisors and managers of those you have trained. In the follow-up training, gather the data using a reaction form similar to that shown in Figure 6-7 or the sample follow-up questionnaire shown in Figure 6-8.

Follow-Up Training. This is a popular strategy for ensuring that an ROI exists. Design your follow-up campaign to include the supervisors and managers of those you have trained. In the follow-up training, gather the data using a reaction form similar to that shown in Figure 6-7 or the sample follow-up questionnaire shown in Figure 6-8.

The Validation for Your Training Program

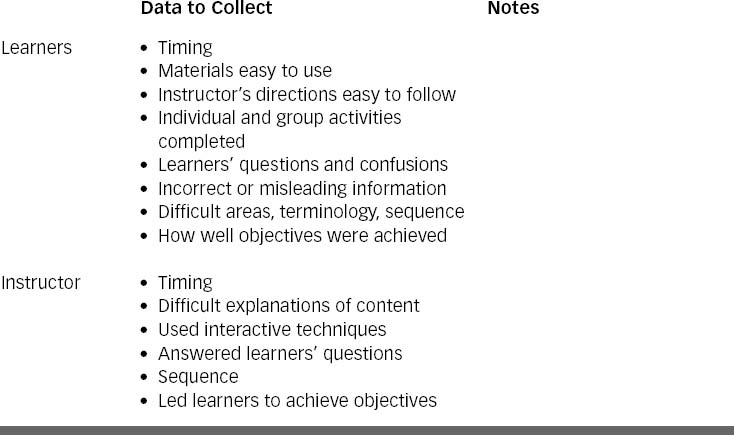

After a training has been completed, there are many ways to validate your training design. Table 6-8 is a checklist for ensuring that you have collected all the relevant data, from both learners and instructors. Check off the items on the list and make appropriate notes in the right-hand margin if you need to follow up on any you have missed. The checklist proves especially helpful because it targets the two dimensions of training: learner achievement and instructor facility with the content.

Figure 6-7. Sample post-meeting reaction form.

DIRECTIONS: Carefully read the statements below and rank-order each using the following scoring process: use 1 to indicate least useful and use 5 to indicate most useful. For each question, first identify the statement you would rank 1, then the one item you rank 5, then 2, 3, and 4. Note: We’ve shown one sample question here; depending on the nature of your meeting, add more questions to solicit the information you need.

1. During the meeting, participants were

( ) uninterested and uninvolved.

( ) in need of help.

( ) involved in process issues.

( ) strictly task oriented.

( ) involved in learning.

2. Additional questions ….

Figure 6-8. Sample follow-up questionnaire for program participants.

Name of Course: ___________________________________ Date: _________________

DIRECTIONS: Answer the following questions, based on the training you received. There are no right or wrong answers; honest responses are appreciated and will be used to improve this training program.

1. Which of the topics covered have you applied directly to your work since you attended the training?

2. Describe how you used what you learned in the training:

3. How successful do you think you have been in transferring what you learned to your performance on the job? (Circle one)

Very successful Successful Not very successful

4. What changes in or additions to the training format would you recommend?

Table 6-8. Checklist for validating your training program.

Ensuring the Transfer of Training to the Job

Many factors are important for successful learning and training transfer, but perhaps the most important are learner motivation and expectations, effective training design, trainer personality and skill, opportunity to use the information, support from supervisor and peers, and an organizational culture that supports training. Because the goal of your training program is to ensure training transfer, this is paramount from the point you begin to design a training program.

According to Barbara Carnes, a leading consultant on training, keep these three concepts in mind when designing a training:

1. Consider the critical time frames. There are three points in time that influence training transfer: before the training, during the training, and after the training. The most important of these are before the training, when positive expectations of the utility of the training and supervisor support should take place; and during the training, when the trainer/instructional designer skill and personality are used.

2. Identify the barriers. There are several barriers to successful training transfer: no opportunity to use the newly acquired skills, no support or encouragement from the supervisor or the rest of the organization, training received that is not applicable to the job, low or poor expectations prior to the training, supervisor or peer pressure to ignore the new skills, and no motivation to use the new skills.

3. Integrate the education. (TIEs) are easy-to-use teaching methods for before, during, or after the training that increase the chances that training transfer will take place. These techniques are within the control of the trainer, although they may also involve the trainee or the supervisor, and they can be incorporated into any training program, regardless of content.

The following are 12 techniques that you can use to ensure training transfer.

1. Target objectives

![]() Start with SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-based) instructional objectives.

Start with SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-based) instructional objectives.

![]() Invite personalization.

Invite personalization.

![]() Use pre-work, in writing.

Use pre-work, in writing.

2. Success stories and lessons learned

![]() Use before, during, or after the training.

Use before, during, or after the training.

BEFORE: Previous graduates share success stories on using their new skills

DURING: Trainer shares these stories

AFTER: New graduates share success stories and lessons learned

• Use e-mail or voicemail.

• Use a memo of success stories, and make connections.

3. Training buddies

![]() Use before, at the beginning, at the middle, at the end, and after the training.

Use before, at the beginning, at the middle, at the end, and after the training.

![]() Assign or let participants choose.

Assign or let participants choose.

![]() Share goals.

Share goals.

![]() Agree to support, help, and hold accountable.

Agree to support, help, and hold accountable.

![]() Combine with other TIEs.

Combine with other TIEs.

![]() Reinforce.

Reinforce.

4. Picture yourself

![]() During: Trainer leads visualization: “Picture yourself with these new skills….” Trainees draw pictures of themselves using the new skills. Trainees discuss benefits.

During: Trainer leads visualization: “Picture yourself with these new skills….” Trainees draw pictures of themselves using the new skills. Trainees discuss benefits.

![]() After: Discuss/visualize the application. Trainer leads visualization: “Draw a picture of how you are going to use this new training.”

After: Discuss/visualize the application. Trainer leads visualization: “Draw a picture of how you are going to use this new training.”

5. Training tickets

![]() Before: Send ticket or memo to introduce content, outcomes, expectations, and access prior to learning. Collect ahead of time to customize the class. Send to supervisor, too.

Before: Send ticket or memo to introduce content, outcomes, expectations, and access prior to learning. Collect ahead of time to customize the class. Send to supervisor, too.

![]() During: Start the training with them. Use to assign training buddies. Trainer says, “To gain admission, bring it with you or send it in. Ask the boss to complete it for you to identify mutual goals.”

During: Start the training with them. Use to assign training buddies. Trainer says, “To gain admission, bring it with you or send it in. Ask the boss to complete it for you to identify mutual goals.”

6. Application check

![]() During: Several times during the training have participants write how they will use what they are learning.

During: Several times during the training have participants write how they will use what they are learning.

![]() After: Send to participant to remind and reinforce.

After: Send to participant to remind and reinforce.

7. Measure it

![]() Before: Pre-test for prior learning. Give feedback results to participant.

Before: Pre-test for prior learning. Give feedback results to participant.

![]() During: Give feedback to instructor and participant.

During: Give feedback to instructor and participant.

![]() After: Post-test to determine learning six weeks to nine months later to determine transfer, and include their managers.

After: Post-test to determine learning six weeks to nine months later to determine transfer, and include their managers.

8. Transfer trivia

![]() Measure learning informally.

Measure learning informally.

![]() Use board games, index cards, or paper.

Use board games, index cards, or paper.

![]() Write your own content questions, or borrow them from course materials such as post-course tests or review questions.

Write your own content questions, or borrow them from course materials such as post-course tests or review questions.

![]() Award prizes.

Award prizes.

![]() Before: Use as pre-test or introduction.

Before: Use as pre-test or introduction.

![]() During: Reinforce or test learning.

During: Reinforce or test learning.

![]() After: Test learning or transfer.

After: Test learning or transfer.

9. Critical mass feedback

![]() Chart to show how many in the work unit or department have been trained.

Chart to show how many in the work unit or department have been trained.

![]() With manager, set completion goal: 100%, 75%, etc.

With manager, set completion goal: 100%, 75%, etc.

![]() Before: Feedback to supervisor and trainee to motivate enrollment.

Before: Feedback to supervisor and trainee to motivate enrollment.

![]() After: Show progress toward goal, and stimulate future enrollments. Post or send via memo or e-mail.

After: Show progress toward goal, and stimulate future enrollments. Post or send via memo or e-mail.

10. Use it or lose it checklist

![]() During: List or have participants list specific things to do back at work to apply the training. Send their supervisor a copy.

During: List or have participants list specific things to do back at work to apply the training. Send their supervisor a copy.

![]() After: Follow up. Recognize/reward completed checklist.

After: Follow up. Recognize/reward completed checklist.

11. Play bingo

![]() After: On each box on the card, list one activity to apply training. Get managers to help identify activities. Customize for different departments. Offer prizes for blackout. Do electronically.

After: On each box on the card, list one activity to apply training. Get managers to help identify activities. Customize for different departments. Offer prizes for blackout. Do electronically.

12. Action plan

![]() Use before, during, or after.

Use before, during, or after.

![]() List activities or actions to take after training.

List activities or actions to take after training.

![]() Have trainee, supervisor, and trainer sign.

Have trainee, supervisor, and trainer sign.

![]() Write formal contract with commitment to learn and use (trainee); guide and support (supervisor and trainer).

Write formal contract with commitment to learn and use (trainee); guide and support (supervisor and trainer).

![]() Give copies to all: trainee, trainer, and manager.

Give copies to all: trainee, trainer, and manager.

![]() Follow up.

Follow up.

Linking the Training to the Bottom Line

Today there is a call for accountability in training. Measuring the effectiveness of training, its business value, and its ROI are frequent topics of conversation when training plans are being reviewed or funded by upper management. Thus, evaluation of training results is vital for reinforcing the value of training. It is also a vital link between you and the client organization or its stakeholders.

Training represents a change project in any organization, and correspondingly there are levels of training evaluation in regard to any change effort:

![]() The first level measures how well each task is performed within the total project scheme before any changes or training is performed. The goal is to determine the performance of each individual involved.

The first level measures how well each task is performed within the total project scheme before any changes or training is performed. The goal is to determine the performance of each individual involved.

![]() The second level is the observation of individuals, units, and departments to determine how they handle the new processes dictated by the change project.

The second level is the observation of individuals, units, and departments to determine how they handle the new processes dictated by the change project.

![]() The third level is the measurement of the impact of meta-tasks and how these tasks impact the organization.

The third level is the measurement of the impact of meta-tasks and how these tasks impact the organization.

Let’s look at each of these levels.

Short-Term Evaluation

The first level mentioned above consists of short-term projects within the larger change process. This usually involves analyzing the implementation of a challenging task, and it provides the change team with necessary feedback on how well the project is progressing. It can provide feedback on how the project is being managed and can indicate if anything needs to be added, adjusted, or eliminated. During this level, adjustments to the project can be made.

Given the fact that there are individuals working on the change project team, an evaluation tool is used merely to provide these individuals with an opportunity to share their experiences, get help, hear from others, and come to some mutual agreement as to what the present state of the project looks like. There are two tools that are recommended to conduct this short-term evaluation: oral reviews and project sessions.

Oral Review. An oral review is a series of well-framed questions. You want to have each of the change team members and other managers or supervisors deemed necessary to explain what they see in the project that needs attention. When you design the questions, structure them around a key project indicator or action step. This creates strong redundant data patterns. Also, never answer your own questions because that allows the participants to stop thinking, and it defeats the purpose of the review.

When conducting the oral review, do not tackle large tasks or chunks of material at once. Break down the information you want to gather in short, simple sentences. Also, keep the review short and to the point. Don’t let the review become a gripe session. Look for effective redundant loops of information. Be consistent. Review regularly, and don’t miss a chance to review. Develop a schedule, and stick to it.

Reviews only provide feedback and evaluation of what the impressions are of those involved, so try to quantify the information they provide. To enlist people to attend the oral review, summarize the feedback that members have provided and give a perspective on what they have done and what is the next step. This process keeps everyone in the habit of reviewing the project on a regular basis and prevents surprises.

Project Session. A project session is a meeting of all members involved in the change project. There are several ways to conduct the session. For instance, ask each person to bring a critical incident in the project (a critical incident is an event that the individual recently experienced that was crucial to or had a significant effect on the task performance). Collect the incidents, choose the most germane, and assign groups to work on evaluating and solving the incident.

Another type of project session is the case history, usually structured around a single large problem that must be solved. If there is a persistent problem with a task, assign the group most immediately involved to write a case history. The case is then presented, and the entire group studies the situation and comes up with solutions.

Immediate Application

The second level consists of medium-term feedback loops that are evaluated during the change process. This usually consists of observing the performance of a task within the project. The performance evaluation focuses on ensuring that the tasks are completed appropriately, and that the individuals completing the job know what they are doing and why they are performing the task. The aim is to gather feedback from those doing the specific task. Just as in the first level, findings now can lead to adjustments to the project. There are four steps to follow in conducting the second level of evaluation:

1. Review the action plans in the job setting. At the completion of each task, have the task leader use an evaluation technique to assess if the individuals working the plan know what they have done. This assessment might consist of having the individuals write a simple synopsis of what they did and then sharing it with the group. This activity checks for understanding of the action plan being put into place.

2. Set key variables or techniques. Develop a technique with the group that they must use while putting the action plans into operation. Check with the group to see if they used the technique and if they modified it. If there was a degree of modification to make it their own, this is an evaluation that the group is applying the technique they learned on the change project.

3. Let the project team know that at some future date they will be asked to respond to a survey. Ask them what type of questions they think would be important to ask in the future. If the questions are appropriate for evaluating progress, use them in the survey.

4. Let the group know that you have planned to hold group sessions during well-spaced intervals. This provides the opportunities for individuals to offer input and to hear from others working on other tasks. You can use an assessment tool, case studies, project studies, dialogue, or role-playing events.

The second level really focuses on the individuals who are taking the project action back to their own units, programs, or departments. It’s important to provide structured events to have them share their experiences of working on tasks and to hear from others.

Bottom-Line Evaluation

To move from a reactive to a proactive status, the team must become an integral part of the organization’s strategic planning. This means that the change project must be evaluated in terms of the bottom line. If the change is to have a positive effect on the organization, there needs to be evidence of both qualitative and quantitative data.

The first thing that the change team must consider, if they choose to adopt this level of evaluation process, is how to establish a relationship between costs of the existing situation and costs as a result of the change. This is not a matter of justifying costs; it is an exercise to prove that there is a reason for initiating the change. It has to consider, therefore, the opportunity cost of not making the improvement. Thus, the third level is a measure of the impact of change on the organization at large. The proposed change can relate to the mission statement, a budget difference, department goals, or other outcome of making a change, but its purpose is to assess how the change project will succeed and how that success will be measured. Ultimately, the change team discusses the impact of the third level and determines if it is an action that is necessary to performance.

Closing Activities

All training programs come to an end. Below are closure techniques and activities you can use to end your training.

Inter-Twined

This activity demonstrates the effect of team members’ actions on one another. It is a good closure to teambuilding workshops.

1. Break participants into groups of four or five, and give each a ball of twine.

2. Read the following:

DIRECTIONS: Consider yourselves a team. Cluster together. Be no farther than an arm’s length from the teammate next to you. One person takes the ball of twine, holds onto the end of the twine, and passes the ball to a teammate. That teammate holds onto a segment and passes the ball to another teammate—it can be the teammate next to you or across from you. Keep the twine taut without breaking it. You are encouraged to make complex, multiple loops around each other. You can loop the twine around one or two other teammates. Your looping pattern will demonstrate how creative you are as a team—and you are creative. Continue this process until every member of the team is holding the twine at some point.

3. When the team is all connected, tell them to try these actions in sequence, one after the other:

![]() One teammate moves hand to the right.

One teammate moves hand to the right.

![]() Another teammate moves to the corner of the room.

Another teammate moves to the corner of the room.

![]() Another teammate sits down.

Another teammate sits down.

![]() Another teammate moves back to where the exercise began.

Another teammate moves back to where the exercise began.

4. Reconvene the large group, and lead a discussion on how the exercise demonstrates the effect of one person’s actions on others in a group, such as work teams or committees.

Participant Summaries

Typically, trainers end a program by summarizing their training program. These summaries have the potential to be disengaging and dry. One way to counteract this potential is to have participants create their own summaries. The primary purpose is to provide participants with an opportunity to evaluate the information they have learned and present it in a meaningful way. The secondary purpose is to provide trainers with immediate feedback on the course and know that the participants gained the ability to integrate the information they have learned.

Use this closer, which takes 90 to 120 minutes, for longer nontechnical trainings such as leadership development, professional development, safety management, or process improvement. The materials you will need include flip charts, a box of markers, computers with presentation software, scissors, and tape. Follow these directions:

Step 1. Divide participants into groups. Use your judgment as to the makeup of the groups. Consider the complexity of course content and participant representation, such as organization, roles, level, and expertise. Each group will focus on one main area of content.

Step 2. Assign each group a topic or allow groups to select their own. Each group creates a 20-minute review of their topic using any format. Formats could include presentation, role-play, panel discussion, or facilitated discussion. Participants should be encouraged to be creative. Provide the following:

INSTRUCTIONS: Your group has 15 to 20 minutes to lead a review session on your topic. Ensure your review is interactive and involves the other participants. Consider the following items in your review:

![]() Explain the most important aspects of your topic.

Explain the most important aspects of your topic.

![]() Describe how your group will use the information on the job.

Describe how your group will use the information on the job.

![]() Describe how your thinking has changed as a result of the training.

Describe how your thinking has changed as a result of the training.

![]() Explain what you will do differently as a result of the training.

Explain what you will do differently as a result of the training.

![]() Demonstrate how to apply tools or concepts.

Demonstrate how to apply tools or concepts.

![]() Share what conclusions you have reached.

Share what conclusions you have reached.

Step 3. Provide groups with 45 to 60 minutes to prepare their review. This is a self-directed activity, and the trainer should only be available to answer questions.

Step 4. Have groups lead their reviews. The other groups are participants and should ask questions and follow directions.

Step 5. Lead a debriefing by asking the following types of questions:

![]() What was the process like for creating your own course review?

What was the process like for creating your own course review?

![]() What types of skills did you use in leading your reviews?

What types of skills did you use in leading your reviews?

![]() What did you like about other groups’ reviews?

What did you like about other groups’ reviews?

Poetic Experience

This is a good concluding activity for any length class and also serves as a fine lead-in to the level one evaluation. The purpose of this closer is to provide participants with an opportunity to express their reactions to the class.

For this activity, which will take 40 minutes, you need poetry magnets or slips of paper with a variety of words typed on them and card stock or cardboard and tape.

Step 1. Break participants into groups, and provide each group with a box of magnetic poetry words and a piece of card stock. Inform participants that they are to work together, using the words provided, to create a poem about their reactions to the class or to the content of the program. Share the definition of a poem, such as this one: “Writing that formulates an imaginative awareness in language chosen to create a specific emotional response.” The poem can be humorous or serious, but it should reflect the group’s opinion of the training. To get things started, the trainer can provide a poem example that describes the class. Allow 25 minutes for the activity.

Step 2. Participants can spend 10 to 15 minutes reviewing the poems.

Step 3. Lead a debriefing session by asking questions such as the following:

![]() How did the group develop the process of creating its poem?

How did the group develop the process of creating its poem?

![]() Did you notice any themes emerging in all of the poems?

Did you notice any themes emerging in all of the poems?

![]() Why did your group choose its topic?

Why did your group choose its topic?

Step 4. Take a picture or make copies of the poems so you have evidence to supplement an evaluation report or as the basis for future classes.

Blended Learning in the Work Environment

When more than one delivery mode is used, with the objective of optimizing the learning outcomes and the cost of administering the program, this is termed blended learning. However, it is not the mixing and matching of different delivery modes that makes this program style significant but, rather, its focus on learning and business outcomes. Blended learning gives participants valuable ways to assess, focus, measure, and reinforce the knowledge they gain by delivering targeted and actionable content at key stages. The goal of blended learning is long-term retention, improved mastery of subject matter, and markedly greater on-the-job performance.

There are various feedback devices that you can use to assess the success levels that will result from blended learning. These devices provide valuable information that alerts you to any need to adjust the training while ongoing, so you don’t have to wait until the end to uncover problems with presentation.

1. Pre-Training Assessments. Prior to the training, participants use online tools to assess their subject-matter knowledge, identify areas of potential development, and create an individualized learning plan that focuses their learning on those goals.

2. Instructor-Led Seminars. Most learning is acquired during a live course led by an instructor who is an expert in the field. During this phase, learners refer to the learning plan they developed in pre-training assessments.

3. Post-Assessments. After the instructor-led training has concluded, participants complete an online post-seminar assessment to measure what they’ve learned.

4. Tune-Up Courses and Other Online Resources. Retraining and subsequent building on new knowledge is the first step to achieving subject-matter mastery. Any remaining knowledge gaps are identified in the post-seminar assessments and are eliminated with targeted online tune-up courses.

5. Measurements. Through comparisons of pre- and post-assessments, the training program designer can measure the transfer of learning and report the effectiveness of the training to the organization, thereby demonstrating a return on the training investment.

6. Lasting Resources for the Employees and the Organization. Months after the program has ended, participants can go online to select refresher topics and apply them to the job.

Attributes of Blended Learning

Originally, the term blended learning was applied to the linking of traditional classroom training to e-learning activities. However, it has evolved to encompass a much richer set of learning strategies. Today, a blended learning program may combine one or more of the following dimensions, although many of these have overlapping attributes.

Offline and Online Learning

Blended learning sometimes combines online and offline forms of education, where online usually means “over the Internet or intranet” and offline happens in a classroom setting. For example, a program may provide study materials and research resources over the Internet while using instructor-led classroom training as the main medium of instruction.

Self-Paced and Live Collaborative Learning

Self-paced learning implies solitary, on-demand learning at a pace that the learner manages. Collaborative learning, on the other hand, implies dynamic communications among several learners. Thus, this form of blended learning may include individual review of important literature on a regulatory change or new product, followed by a moderated, online, peer discussion of that material’s application.

Structured and Unstructured Learning

Not all forms of learning involve a structured program with organized content, presented in a specific sequence like chapters in a textbook. In fact, most workplace learning occurs in an unstructured form, such as in meetings, in hallway conversations, and through e-mail. A blended program captures conversations and documents from these unstructured situations and places them in knowledge repositories where content is available on demand—paralleling the way workers collaborate at work.

Custom and Off-the-Shelf Content

Off-the-shelf content is, by definition, generic, so it cannot cover an organization’s unique context and meet specific requirements. However, it is much less expensive and frequently has higher production values; that is, greater results from more money being spent on design, development, delivery, and production of training than custom content. Generic, self-paced content can be tailored to suit an organization’s needs with a blend of live experiences (classroom or online) and limited content customization. Industry standards such as SCORM (Shareable Courseware Object Reference Model) can offer greater flexibility in blending off-the-shelf and custom content, thereby improving the user experience while keeping costs at minimum.

Work and Learning

The true effectiveness of learning for any organization is the paradigm of inseparable work (such as business applications) and learning, whereby learning is embedded in the business processes, such as hiring, sales, or product development. That is, work becomes a source of shared learning and learning is a constant in the workplace. In this paradigm, constraints of time, geography, and format that we associate with the traditional classroom are no longer valid. Even the fundamental organization of a training course can be transformed into an ongoing learning process.

Ingredients for Today’s Blended Learning

Blended learning is not new. However, in the past the ingredients were limited to formats used in traditional classroom formats (lectures, labs, books, or handouts). Today, trainers have myriad learning approaches, including but not limited to the following:

![]() Synchronous physical formats: instructor-led classrooms and lectures, hands-on labs and workshops, field trips

Synchronous physical formats: instructor-led classrooms and lectures, hands-on labs and workshops, field trips

![]() Synchronous online formats (live e-learning): e-meetings, virtual classrooms, Web seminars and broadcasts, instant messaging

Synchronous online formats (live e-learning): e-meetings, virtual classrooms, Web seminars and broadcasts, instant messaging

![]() Self-paced, asynchronous formats: documents and Web pages, Web/computer-based training modules, assessments/tests and surveys, simulations, job aids, online learning communities and discussion forums

Self-paced, asynchronous formats: documents and Web pages, Web/computer-based training modules, assessments/tests and surveys, simulations, job aids, online learning communities and discussion forums

As mentioned above, the concept of blended learning is rooted in the idea that learning is not just a one-time event but, rather, a continuous process. Blending provides various benefits over using a single learning type because it avoids the limitations of a single delivery mode. For example, a scheduled classroom training program limits access to those who can participate at that time and in that location, whereas a virtual classroom is inclusive of a remote audience and when supported by a recorded version (the ability to replay a recorded live event) can be revisited for review or greater clarification.

Getting Started with Blended Learning

The training designer or instructor needs to approach blended learning as a journey rather than a destination. The first steps are to build content experience with self-paced learning techniques and live e-learning, thereby understanding their strengths and weaknesses in your training context. The good news is that this initial step consistently demonstrates quick financial payback and strong user acceptance.

The next step is to experiment with dimensions of the blend. You may find it useful to link self-paced content with live learning activities. Whichever elements you decide to blend, approach the design as you would in making any significant organizational change. That is, ensure that the following project criteria can be met:

![]() There is clear, high-value business justification to achieve executive sponsorship.

There is clear, high-value business justification to achieve executive sponsorship.

![]() Executive sponsorship will provide the resources and management support required.

Executive sponsorship will provide the resources and management support required.

![]() A committed project team will execute the project regardless of obstacles.

A committed project team will execute the project regardless of obstacles.

![]() A change management strategy exists to anticipate and overcome resistance to change.

A change management strategy exists to anticipate and overcome resistance to change.

![]() There are responsive vendors to provide resources and expertise.

There are responsive vendors to provide resources and expertise.

![]() You have a deadline that helps you maintain focus and commitment.

You have a deadline that helps you maintain focus and commitment.

E-Learning and Technology for Blended Learning

As with all instructional strategies, technological innovations for training purposes have their own strengths and limitations. In general, technology-based learning systems require more upfront work and more money than traditional methods and will usually be more complex to implement and manage. However, once the systems are up and running, they can be convenient and cost-effective ways to deliver learning.

There is a lot of talk these days about e-learning. Most people consider e-learning to be learning via electronic or online means, using a computer. Actually, the scope of e-learning goes a bit deeper than that. SmartForce, a large provider of online learning systems, considers e-learning to mean “to experience learning.” The company applies it to other “e-words,” such as enterprise, excellent, everywhere, and electronic. People using advanced “definitions” of e-learning understand that adult learning principles are at the heart of their total learning solution.

Simply put, e-learning is used to meet the demands of today’s organizations and today’s individual learners. It is viewed as the best technology to deliver learning that meets all of the following criteria:

![]() Flexible (can be configured quickly to meet different learning needs)

Flexible (can be configured quickly to meet different learning needs)

![]() Fast and available (can often be started immediately, and instruction “comes” to the learner)

Fast and available (can often be started immediately, and instruction “comes” to the learner)

![]() Convenient (can often be done at the learner’s location and at the learner’s convenience)

Convenient (can often be done at the learner’s location and at the learner’s convenience)

![]() Tailored to the learner (can be adapted to suit the learner’s abilities, interests, and existing knowledge)

Tailored to the learner (can be adapted to suit the learner’s abilities, interests, and existing knowledge)

![]() Economical (usually far less costly than face-to-face training and reduces or eliminates travel costs)

Economical (usually far less costly than face-to-face training and reduces or eliminates travel costs)

![]() Interactive (can be an engaging and effective way to learn)

Interactive (can be an engaging and effective way to learn)

![]() Enterprise-wide (can be standardized for use across the organization)

Enterprise-wide (can be standardized for use across the organization)

![]() For everyone (can be accessed by more people than traditional settings)

For everyone (can be accessed by more people than traditional settings)

Components of Learning Technology

To take advantage of the power and flexibility of learning technology, e-learning experts recommend you build a variety of learning methods into a comprehensive solution. This total-solution concept supports the greatest range of needs and learning styles. Whichever methods you choose, however, consider each of these components of learning technology:

![]() Asynchronous Content Delivery. There needs to be a way for learners to receive and explore the content whenever they have the time. Asynchronous means that the learner is not required to connect with the material at the same time as an instructor or other learners. Instead, the interaction is with the computer and the material that others have previously made available. Examples of asynchronous content delivery include Web-based learning modules, CD-ROM programs, structured courseware, Web site links, and libraries of published articles. None of these requires direct interaction with another person.

Asynchronous Content Delivery. There needs to be a way for learners to receive and explore the content whenever they have the time. Asynchronous means that the learner is not required to connect with the material at the same time as an instructor or other learners. Instead, the interaction is with the computer and the material that others have previously made available. Examples of asynchronous content delivery include Web-based learning modules, CD-ROM programs, structured courseware, Web site links, and libraries of published articles. None of these requires direct interaction with another person.

![]() Synchronous Content Delivery. It is often helpful for a learner to be able to ask questions of the instructors, experts, or peers, and to learn more than the programmed instruction allows. Attending online classes, meetings, or presentations provides this synchronous, or same-time, two-way communication, usually via chat-based classes, video or satellite classes, or Web meeting classes.

Synchronous Content Delivery. It is often helpful for a learner to be able to ask questions of the instructors, experts, or peers, and to learn more than the programmed instruction allows. Attending online classes, meetings, or presentations provides this synchronous, or same-time, two-way communication, usually via chat-based classes, video or satellite classes, or Web meeting classes.

![]() Supplemental Learning Resources. Collaboration is an advantage of the e-learning environment. Learners can discuss problems, work on joint assignments or projects, and gain a sense of community through bulletin boards, online chats, discussion groups, and instant messaging sessions. Job aids are another type of learning supplement that helps learners apply what they learn.

Supplemental Learning Resources. Collaboration is an advantage of the e-learning environment. Learners can discuss problems, work on joint assignments or projects, and gain a sense of community through bulletin boards, online chats, discussion groups, and instant messaging sessions. Job aids are another type of learning supplement that helps learners apply what they learn.

![]() Work Applications. To be effective at improving performance, e-learning solutions need to help learners transfer the learning to the job. Often, opportunities for this transference need to be designed into the total solution, as it is not a component of the course itself. Examples of work applications include on-the-job projects or assignments, links of the material to real-work situations, and expectations of accountability for using what the person learns.

Work Applications. To be effective at improving performance, e-learning solutions need to help learners transfer the learning to the job. Often, opportunities for this transference need to be designed into the total solution, as it is not a component of the course itself. Examples of work applications include on-the-job projects or assignments, links of the material to real-work situations, and expectations of accountability for using what the person learns.

![]() Support Methods. In the e-learning environment, learning is not limited to a set class period or training session. Learners can get ongoing help, support, and advice through online coaching and mentoring, help files, frequently asked questions files, and organizational teaching support.

Support Methods. In the e-learning environment, learning is not limited to a set class period or training session. Learners can get ongoing help, support, and advice through online coaching and mentoring, help files, frequently asked questions files, and organizational teaching support.

![]() Assessments. Online tools allow learners to complete pre- and post-training skills assessments, as well as surveys that customize the course to their needs and abilities. For certification or qualification programs, the computer can be programmed to automatically administer, score, and record the certification tests.

Assessments. Online tools allow learners to complete pre- and post-training skills assessments, as well as surveys that customize the course to their needs and abilities. For certification or qualification programs, the computer can be programmed to automatically administer, score, and record the certification tests.

Limitations of Learning Technology

Most new training technologies are an improvement over the static classroom methods used in the past, largely because they create a more positive learning environment. However, developmental costs can be high and programs can become obsolete quickly.

To decide whether to integrate technology into your training program, consider the monies and time needed for product development, the geographic location of prospective individuals and learning groups, and the inherent difficulties in getting employees to attend training sessions. Also, consider which methods best support the organization’s business strategy and produce effects that can be used on the job. Below are some disadvantages to using technology in the training program:

![]() Learners must be computer-literate and have routine access to computers. In most cases, the learners also need routine access to the Internet, the organization’s computer network, or both.

Learners must be computer-literate and have routine access to computers. In most cases, the learners also need routine access to the Internet, the organization’s computer network, or both.

![]() E-learning frequently requires a larger upfront cash investment than traditional methods, often involving software licenses and customization courseware (if needed).

E-learning frequently requires a larger upfront cash investment than traditional methods, often involving software licenses and customization courseware (if needed).

![]() The planning, design, and implementation of e-learning require coordination across training and IT functions.

The planning, design, and implementation of e-learning require coordination across training and IT functions.

![]() Custom course development using technology involves more detailed work and usually costs a lot more (up to ten times more, for detailed multimedia) than traditional learning methods.

Custom course development using technology involves more detailed work and usually costs a lot more (up to ten times more, for detailed multimedia) than traditional learning methods.

![]() Computer-based instruction is inherently limited in the complexity it can handle because all options must be programmed into the courseware. This makes it less suitable for practice of social-interaction skills (coaching, leadership, sales), where every interaction is different.

Computer-based instruction is inherently limited in the complexity it can handle because all options must be programmed into the courseware. This makes it less suitable for practice of social-interaction skills (coaching, leadership, sales), where every interaction is different.

Implementing an E-Learning Program

Making the move from classroom training to a mix of classroom and e-learning requires a shift in expectations and skills sets. For the effort to be successful, the organization needs to accept changes in its culture. Here are some of the keys essential to implementing e-learning:

![]() Learning Expertise. It should be no surprise that the organization needs experts who understand how people learn. Sound knowledge and application of adult learning theories drive e-learning as much as (or more than) traditional learning attempts.

Learning Expertise. It should be no surprise that the organization needs experts who understand how people learn. Sound knowledge and application of adult learning theories drive e-learning as much as (or more than) traditional learning attempts.

![]() Learning Experts Who Understand Technology. The learning expert must not only understand how the technology works but also be aware of its strengths and limitations. In the e-learning environment, technology is the medium and the training content is the message. Many organizations have found that relatively few trainers can make the transition to online delivery. Training skills sets and competencies are different in the e-learning environment.

Learning Experts Who Understand Technology. The learning expert must not only understand how the technology works but also be aware of its strengths and limitations. In the e-learning environment, technology is the medium and the training content is the message. Many organizations have found that relatively few trainers can make the transition to online delivery. Training skills sets and competencies are different in the e-learning environment.

![]() Clear Judgment. Organizational decision makers need to remain focused on the learning and performance-improvement goals. E-learning should not be done just because it can be done or because other organizations are doing it. Make sure that it is a good choice for the learning needs and the situation.

Clear Judgment. Organizational decision makers need to remain focused on the learning and performance-improvement goals. E-learning should not be done just because it can be done or because other organizations are doing it. Make sure that it is a good choice for the learning needs and the situation.

![]() Infrastructure. The organization must have the commitment of the IT group and a stable and reliable organizational computing network. The learners must also have routine access to networked computers on which to access and do the learning.

Infrastructure. The organization must have the commitment of the IT group and a stable and reliable organizational computing network. The learners must also have routine access to networked computers on which to access and do the learning.

![]() Upfront Budget. Licensing software and building an e-learning infrastructure almost always entail an upfront charge. The cost savings can be great when compared to traditional training logistics, but organizations should expect the initial investment to be higher.

Upfront Budget. Licensing software and building an e-learning infrastructure almost always entail an upfront charge. The cost savings can be great when compared to traditional training logistics, but organizations should expect the initial investment to be higher.

![]() Time to Become Used to New Methods. For e-learning to be accepted, there needs to be a strong organizational commitment to training and learning.

Time to Become Used to New Methods. For e-learning to be accepted, there needs to be a strong organizational commitment to training and learning.

Learning Technology Success in the Blended Learning Application

To ensure success for your blended learning applications, consider the following criteria in evaluating the learning technologies available to you.

1. Ease of Navigation. How easy is it for learners to get to the learning site and to find their way around within the learning package? Look for clear, simple navigation tools, bookmarks, and the option to skip ahead or go back to review material previously covered.

2. Content/Substance. What is the quality of the instructional content itself? Look for references to models and theories that are supported with research, as well as demonstrations of practical utility. Does the content reflect proven principles, or is it based on a fad? How easily can content be added, deleted, or upgraded by your training staff and technical support?

3. Layout/Format/Appearance. How well does the package present a clean, professional appearance? Look for graphics and a visual style that enhance learning points. Also look for sound and animation options, where appropriate to the learning need. Would learners take it seriously at first glance?

4. Interest. How well does the instructional content keep learners’ interest? Look for frequent opportunities for the learners to click, type, move, or otherwise interact with the software in a meaningful way. Instruction that allows learners to generate their own ideas and use them in the instruction meets adult-learning principles better than page-turner packages.

5. Applicability. How applicable is the instructional content to the specific need and situation your learners face? Look for a strong connection between the course content and what your learners need to actually do on the job.

6. Cost-Effectiveness/Value. How cost-effective is this learning package when all supporting costs and licenses are figured in? Can the package be charged on a pay-as-you-go plan, or is a large user-license fee required? Does the package require hosting on a server? If so, who will provide that? What kind of support is necessary and included?

Note

1. Donald L. Kirkpatrick, Evaluating Training Programs (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1994).