CHAPTER TWO

Design the Learning to Fit the Need

In this development step of the design and delivery model, you will begin to write your instructional materials and learning activities. Though the mechanics of project design are essential for a good program, they are based on an understanding of instructional systems. Therefore, the chapter has two parts: the first part gives you the specific steps to follow in designing the training program; the second part offers a general discussion of learning theory.

Beginning Your Program Design

The choice of appropriate instructional materials and methods is, at best, a guess if you have not been able to conduct a formal training needs assessment. One way to avoid mismatching an instructional method with a particular audience is to be sensitive to an organization’s demographics and preferences.

In all cases, the word that guides your choice is appropriate use of instructional technologies. The instructional technology you use should be appropriate for the audience, the content, the organizational environment, and, most of all, the proposed learning objectives and methods. These preferences provide you with:

![]() A design template to assist in developing the content for your program material

A design template to assist in developing the content for your program material

![]() A checklist for making decisions about the learning activities

A checklist for making decisions about the learning activities

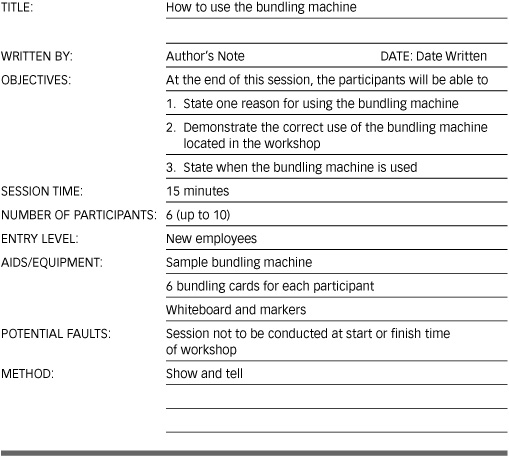

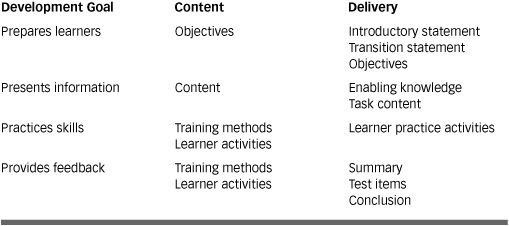

The output of the development stage is a training that is ready to be implemented. Figure 2-1 shows a sample lesson plan.

The development process consists of the following five phases:

Phase One: Develop the following:

![]() Training content

Training content

![]() Graphics

Graphics

![]() Media needs

Media needs

![]() Lesson plans

Lesson plans

![]() Instructor guides

Instructor guides

![]() Evaluation needs

Evaluation needs

![]() Software needs

Software needs

Phase Two: Revise all items in Phase One.

Phase Three: Complete the following.

![]() Conduct the test.

Conduct the test.

![]() Revise the program on the basis of the test.

Revise the program on the basis of the test.

![]() Schedule a second test, if needed.

Schedule a second test, if needed.

Figure 2-1. Sample lesson plan.

Phase Four: Conduct the following.

![]() Pilot-test a prototype program.

Pilot-test a prototype program.

![]() Evaluate the pilot test.

Evaluate the pilot test.

![]() Identify the required revisions.

Identify the required revisions.

![]() Revise the program as required (on the basis of the pilot test).

Revise the program as required (on the basis of the pilot test).

![]() Schedule another test, if needed.

Schedule another test, if needed.

Phase Five: Follow-through on the following.

![]() Finalize the training program content.

Finalize the training program content.

![]() Produce the training program in final form.

Produce the training program in final form.

During the development phase, you will select, write, or otherwise obtain all training documentation and evaluation materials. These may include the following:

![]() Training materials

Training materials

![]() Instructor guide (including lesson plans and a list of required supporting materials)

Instructor guide (including lesson plans and a list of required supporting materials)

![]() Learners’ guide or workbook

Learners’ guide or workbook

![]() Nonprint media (computer software, audiotapes and videotapes, equipment checklists)

Nonprint media (computer software, audiotapes and videotapes, equipment checklists)

![]() Program evaluation materials

Program evaluation materials

![]() Procedures for evaluation

Procedures for evaluation

![]() Supervisors’ form for evaluation of course participants’ post-training job performance

Supervisors’ form for evaluation of course participants’ post-training job performance

![]() Training documentation

Training documentation

![]() Class attendance forms and other records for participants

Class attendance forms and other records for participants

![]() Course documentation (written objectives, authorship and responsibility for course material, lists of instructors and facilitators, and their qualifications)

Course documentation (written objectives, authorship and responsibility for course material, lists of instructors and facilitators, and their qualifications)

What is meant by instruction and instructional methods? The purpose of any training is to promote learning. Instruction promotes learning through a set of developed activities that initiate, activate, and support learning. Use instructional methods to:

![]() Help learners prepare for learning

Help learners prepare for learning

![]() Enable learners to apply and practice learning

Enable learners to apply and practice learning

![]() Assist learners to retain and transfer what they have learned

Assist learners to retain and transfer what they have learned

![]() Integrate your own performance with other skills and knowledge

Integrate your own performance with other skills and knowledge

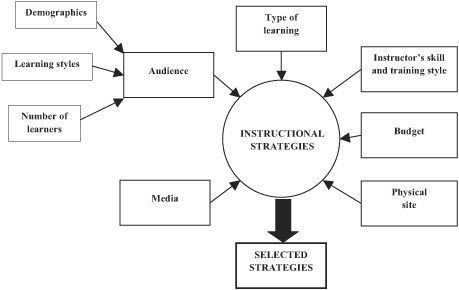

The appropriate method to use depends on a variety of factors, including the following:

![]() Type of learning (verbal information, intellectual skills, cognitive strategy, attitude, or motor skill)

Type of learning (verbal information, intellectual skills, cognitive strategy, attitude, or motor skill)

![]() Audience

Audience

![]() Demographics or profile (age, gender, level of education)

Demographics or profile (age, gender, level of education)

![]() Learning styles (kinesthetic-tactile, visual, auditory)

Learning styles (kinesthetic-tactile, visual, auditory)

![]() Number of learners (individual, small groups, large groups)

Number of learners (individual, small groups, large groups)

![]() Media (selected by appropriateness, number of learners, and financial considerations)

Media (selected by appropriateness, number of learners, and financial considerations)

![]() Budget (funds available for development and presentation)

Budget (funds available for development and presentation)

![]() Instructor’s skills and training style

Instructor’s skills and training style

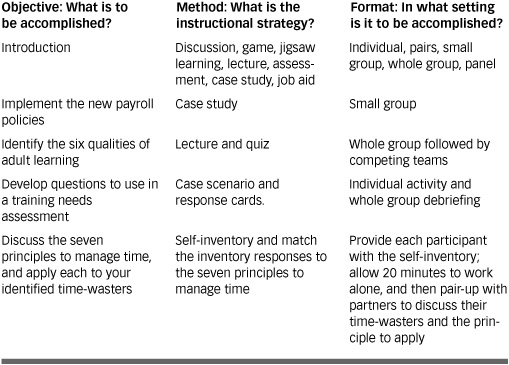

Each factor influences the choice of method for presenting, reinforcing, and assessing retention of the material. A model depicting the relationships among these factors is shown in Figure 2-2.

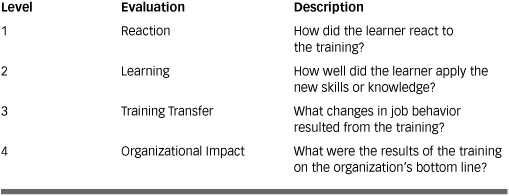

Organizational Needs and Learning Possibilities

Everyone has an interpretation of what training success means. Also, there are so many variables to consider when you try to evaluate success. For example, the learners may see a particular course as a success because the training was fun and they learned a lot that clarified what they do on the job. Yet, suppose an immediate transfer of information to the job does not happen because the learners do not have to execute the task immediately. Does that mean that no training transfer occurred? No, what this brief scenario shows is that results deemed successful depend on the level of evaluation that the training designer has created for the program; for example, suppose the level of evaluation was to test whether the reaction to training is favorable, as shown in level 1 of Table 2-1. Planning your level of evaluation at the same time as you design your course and your instructional strategies is a success factor for your training.

Figure 2-2. Factors influencing instructional strategy.

As Table 2-1 shows, each level of the training model measures a different aspect of the training and affects a different level of the organization. As a trainer or course designer, you can manage to ensure success only at level 1 (Reaction) or level 2 (Learning). To measure success at level 3 (Training Transfer), you have to rely on feedback from the learners’ supervisors/managers or the employees.

Table 2-1. Stages of successful transfer of learning back to the job.

Each level of the Kirkpatrick model evaluates a different aspect of the training; therefore, the question that you must ask yourself when conducting the training is, “Was the training successful, and what level of training transfer am I evaluating?”

Principles of Learning

It’s important to be familiar with the following principles of learning when you are deciding on the training methods to use. (The second part of this chapter gives a more detailed survey of learning theory, but for these purposes you need to know what the ten principles of learning are.)

![]() Part-Learning or Whole-Learning Segments. Part learning is more common than whole learning because trainees prefer to deal with a series of separate assignments. In part learning, the skill or knowledge is divided into parts or segments; in whole learning, the skill or knowledge is viewed as a large, unified block of material. When dividing material into segments, the trainer should follow two guidelines:

Part-Learning or Whole-Learning Segments. Part learning is more common than whole learning because trainees prefer to deal with a series of separate assignments. In part learning, the skill or knowledge is divided into parts or segments; in whole learning, the skill or knowledge is viewed as a large, unified block of material. When dividing material into segments, the trainer should follow two guidelines:

1. The segments should not be too large. Although the subject matter is familiar to you, the material will be new to the learners. Therefore, review the skill or knowledge from the learners’ perspective, and then organize it into segments for training.

2. The segments should follow a logical sequence so that the learners can relate each part to the next. A logical flow of new material will enhance learners’ ability to later recall new skills or information. Proceed from the known to the unknown, moving from one segment to the next after you know, by the learners’ behavior, that the learners have understood and accepted the information. (Caution: Do not oversimplify. After separating the material into segments and developing a logical sequence, check to make sure the segments are not so small as to be boring.)

As an example of whole learning, consider teaching someone to ride a bicycle. This training could be divided into three parts: balancing, steering, and pedaling. But learning each part independently would be difficult because steering depends on balancing and on how hard the pedals are pushed, while balancing depends on steering and pedaling. Teaching someone to ride a bicycle requires whole learning. Whole learning is fairly uncommon, however; more training models are based on part learning.

![]() Spaced Learning. Spaced learning is learning over an extended period of time, in contrast to crammed learning, which is learning a lot of information in a short amount of time. Spaced learning is superior to crammed learning, particularly if learners are to undergo training for a long time. Spaced learning has its basis in what we know about the incubation of knowledge and thought. That is, the brain needs time to as similate new facts before it can accept the next group of new facts. Spaced learning creates opportunities for regular review and revision of what has been learned, which also slows the rate at which learners forget new material.

Spaced Learning. Spaced learning is learning over an extended period of time, in contrast to crammed learning, which is learning a lot of information in a short amount of time. Spaced learning is superior to crammed learning, particularly if learners are to undergo training for a long time. Spaced learning has its basis in what we know about the incubation of knowledge and thought. That is, the brain needs time to as similate new facts before it can accept the next group of new facts. Spaced learning creates opportunities for regular review and revision of what has been learned, which also slows the rate at which learners forget new material.

![]() Active Learning. Actively involving learners in the training, rather than having them listen passively, encourages them to become self-motivated. Active learning is more effective than passive learning, and it is often described as “learning by doing.” Provide learners with plenty of opportunities to practice the skills they learn and think about the information they are absorbing.

Active Learning. Actively involving learners in the training, rather than having them listen passively, encourages them to become self-motivated. Active learning is more effective than passive learning, and it is often described as “learning by doing.” Provide learners with plenty of opportunities to practice the skills they learn and think about the information they are absorbing.

![]() Feedback. The feedback principle of learning has two aspects: constructive feedback to learners on their progress, and performance feedback to instructors on their effectiveness.

Feedback. The feedback principle of learning has two aspects: constructive feedback to learners on their progress, and performance feedback to instructors on their effectiveness.

Feedback to learners can vary in complexity from simply explaining why an answer to a question is correct or incorrect, to commenting on learners’ performance during an activity, to discussing the results of a test. Regardless of the complexity of the feedback, the best feedback is that which is given earliest. The more immediate the feedback, the greater its value, especially for preventing loss of self-confidence and, thus, loss of motivation.

Feedback given to trainers should answer the following questions:

![]() Are learners receiving and understanding the information? (Test them.)

Are learners receiving and understanding the information? (Test them.)

![]() Do learners have doubts or questions? (Ask them.)

Do learners have doubts or questions? (Ask them.)

![]() Are learners paying attention? (Observe them.)

Are learners paying attention? (Observe them.)

![]() Is the session boring? (Observe them.)

Is the session boring? (Observe them.)

![]() Would learners benefit by using more techniques during this session? (Ask them.)

Would learners benefit by using more techniques during this session? (Ask them.)

Two-way communication is critical for feedback’s effectiveness.

![]() Overlearning. Overlearning means learning until the learners have near perfect recall, and then learning the material just a bit more, perhaps through practice. Overlearning decreases the rate of forgetting. In other words, forgetting is significantly reduced by frequency recall or by repeated use of the material. Two important facts to remember in this instance are as follows: (1) Repetition by trainers does not maximize retention; whereas (2) active involvement by trainers does maximize retention.

Overlearning. Overlearning means learning until the learners have near perfect recall, and then learning the material just a bit more, perhaps through practice. Overlearning decreases the rate of forgetting. In other words, forgetting is significantly reduced by frequency recall or by repeated use of the material. Two important facts to remember in this instance are as follows: (1) Repetition by trainers does not maximize retention; whereas (2) active involvement by trainers does maximize retention.

![]() Reinforcement. Positive reinforcement can improve learning because learning that is rewarded is much more likely to be retained. A simple, “Yes, that’s right,” can mean a great deal to a learner and can enhance retention considerably. Positive reinforcement confirms the value of responding and participating and encourages active learning. In contrast, negative reinforcement simply tells learners that their responses were wrong, without providing guidance for making correct responses. Negative reinforcement often discourages learners from further investigation.

Reinforcement. Positive reinforcement can improve learning because learning that is rewarded is much more likely to be retained. A simple, “Yes, that’s right,” can mean a great deal to a learner and can enhance retention considerably. Positive reinforcement confirms the value of responding and participating and encourages active learning. In contrast, negative reinforcement simply tells learners that their responses were wrong, without providing guidance for making correct responses. Negative reinforcement often discourages learners from further investigation.

![]() Primacy and Recency. When learners are presented a sequence of information, they tend to remember what they have heard first and what they have heard last, but they often forget what they have heard in the middle. To guard against this, emphasize and reinforce facts that are in the middle or else present the critical information at the beginning or end of the session.

Primacy and Recency. When learners are presented a sequence of information, they tend to remember what they have heard first and what they have heard last, but they often forget what they have heard in the middle. To guard against this, emphasize and reinforce facts that are in the middle or else present the critical information at the beginning or end of the session.

![]() Meaningful Material. Unconsciously, learners ask two questions when they are presented with new information: (1) Is this information valid relative to my own experiences? and (2) Will this information be useful in the immediate future?

Meaningful Material. Unconsciously, learners ask two questions when they are presented with new information: (1) Is this information valid relative to my own experiences? and (2) Will this information be useful in the immediate future?

The first question emphasizes the notion of movement from the known to the unknown, as well as the fact that people tend to remember material that relates to what they already know. In designing your training, make sure to assess learners’ current level of knowledge.

The second question emphasizes the fact that the learners want to know that what they are about to learn will be useful to them in the near future. Meaningful material links the past and the future and promotes two beneficial effects:

1. Security (when learners move from the known to the unknown)

2. Motivation (information will be useful in the near future)

![]() Multiple-Sense Learning. Research suggests that people will obtain approximately 80 percent of the information they absorb through sight, 11 percent through hearing, and 9 percent through the other senses combined. Therefore, to absorb as much as possible, trainers should design the sessions to use two or more of the senses.

Multiple-Sense Learning. Research suggests that people will obtain approximately 80 percent of the information they absorb through sight, 11 percent through hearing, and 9 percent through the other senses combined. Therefore, to absorb as much as possible, trainers should design the sessions to use two or more of the senses.

Employing sight and hearing in the training is a straightforward task, but designing sessions to use the other senses, such as touch, might be just as crucial for successful learning. For most learning, however, sight is the means for providing the most information, so trainers should emphasize visual aids when designing their sessions.

![]() Transfer of Learning. The amount of knowledge and skills that learners transfer from the training room to the workplace depends mainly on two variables:

Transfer of Learning. The amount of knowledge and skills that learners transfer from the training room to the workplace depends mainly on two variables:

1. The degree of similarity between what they have learned in the training (including how it was presented) and what occurs in the workplace (e.g., can learners apply their new knowledge and skills directly to the job without modifying them?)

2. The degree to which learners can integrate the skills and knowledge gained in the training into their work environment (e.g., does the system at work or the supervisor allow or encourage use of the new skills?)

Be sure to consider these variables as you plan your training. Make three-by-five cards that define the lesson and the outcome objective. These cards then become tools that learners can take with them to use as references back on the job. Develop a checklist of the learning outcomes for the training, and then have learners check off each as they perform the task when they are back on the job. Also, either provide each learner with a journal to record progress after the training, or check with the learners approximately one month after the training to get feedback on the training transfer.

Learning Preferences

Motivated people learn. As you develop your training, assume that the audience is more likely to participate when the setting is conducive to interaction between the trainer and the learners. A learning environment that is relaxed but structured—with an agenda, stated learning objectives, established time frames, and defined tasks—is one in which learners will willingly participate and, therefore, one in which the learning will be successful.

There is a relationship between learners’ demographics and their preferences for particular instructional methods. If you match the audience’s learning preferences to your approach, your design will achieve increased attention and motivation, increased mastery, more successful transfer of information and skills, and enhanced retention and recall.

In most cases, you can collect information about the potential learners during your analysis and design process. The basic audience information you need to know is:

![]() Age (usually a range)

Age (usually a range)

![]() Gender

Gender

![]() Occupation (current as well as previous on occasion)

Occupation (current as well as previous on occasion)

![]() Race or ethnic group (known only occasionally, owing to Equal Employment Opportunity Commission restrictions)

Race or ethnic group (known only occasionally, owing to Equal Employment Opportunity Commission restrictions)

![]() Years of work experience (usually a range)

Years of work experience (usually a range)

The demographics alone do not reveal the learners’ learning preferences, although this is a good starting place. In general, people like group discussions the most, followed by case studies, games, and skill practice. Lectures and telecommunication methods are least liked. Films, intrapersonal and interpersonal training, self-instruction, and computer-based instruction fall in the middle of the preference continuum.

By determining the preferred instructional method for the group you will work with, you are better able to develop and deliver training that appeals to their interests and motivation. Remember that today’s learners want to be excited about the learning event, have fun, learn new things that can be transferred to the job, and not feel bored. By keeping in mind the various trainer styles, learning preferences, and learning environments, you will be able to meet learner expectations.

Course and Module Design

Course design and module design are linked to course development through a series of documents that include the problem analysis, job analysis, and audience profile sheet. From these documents you create your course outline and content map.

The blueprint you create should list the proposed learning objectives. Supportive information about the content is then linked to each learning objective. Training and content experts generally select the instructional content together. They define the course modules and describe how the instructional strategies will be used to introduce the content. In addition, they determine the appropriate learning techniques, develop opportunities for practice, and select the appropriate media. Remember, the media chosen should have a definite purpose— to amplify the learning event, not to entertain a bored audience.

The instructional specifications include the following:

![]() Module title

Module title

![]() Introduction (content summary, utility, importance)

Introduction (content summary, utility, importance)

![]() Sequence of topics and activities (flow, transitions, links)

Sequence of topics and activities (flow, transitions, links)

The Learning Objective

A learning objective is a statement that tells what learners should be able to do when they have completed a segment of instruction. Learning is a cognitive process that leads to a capability that the learners did not possess prior to the instruction. To write learning objectives that are clear, specific, and focused on the learning outcome, begin with this suggested phrase: “At the end of this [course/module], you will be able to.” This opening will help keep the statement outcome-oriented and measurable.

The Three Components of the Learning Objective

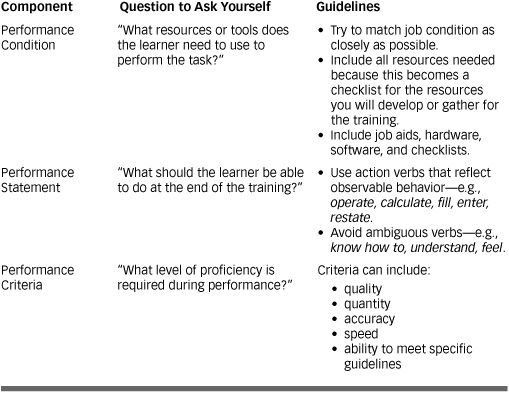

There are three components to a statement of learning objectives, as shown in Table 2-2, and these components are essential for each learning objective: (1) a statement of condition (resources needed); (2) a statement of performance (action desired); and (3) a statement of criteria (standards to be met). Each of these components, when rephrased as a question, reflects an action or behavioral intent.

Table 2-2. Three components of a learning objective.

![]() Condition. Under what conditions do you want the learner to be able to perform the action? A learning objective always states the important conditions, if any, under which performance is to occur. This entails the resources that the learner needs to perform the learned task.

Condition. Under what conditions do you want the learner to be able to perform the action? A learning objective always states the important conditions, if any, under which performance is to occur. This entails the resources that the learner needs to perform the learned task.

![]() Performance. What should the learner be able to do? A learning objective always states what a learner is expected to do as a result of the training. The performance statement is the action desired.

Performance. What should the learner be able to do? A learning objective always states what a learner is expected to do as a result of the training. The performance statement is the action desired.

![]() Criterion. How well must the learner perform? Whenever possible, a learning objective describes how well the learner must perform the new task to be considered acceptable. Thus, all objectives must be specific, measurable, and observable.

Criterion. How well must the learner perform? Whenever possible, a learning objective describes how well the learner must perform the new task to be considered acceptable. Thus, all objectives must be specific, measurable, and observable.

Usually, the statement of a learning objective begins with the performance condition, followed by the performance statement, and then the performance criterion. For example:

![]() Given 10 overdue credit scenarios and the credit agreements for each, the learner will calculate the interest to be paid by each, with no errors.

Given 10 overdue credit scenarios and the credit agreements for each, the learner will calculate the interest to be paid by each, with no errors.

![]() Given three customer scenarios and the guidelines for overcoming customer objections, the learner will role-play overcoming customer objections according to guidelines given by the course instructor.

Given three customer scenarios and the guidelines for overcoming customer objections, the learner will role-play overcoming customer objections according to guidelines given by the course instructor.

Use Table 2-3 to practice how to identify performance conditions and learning objectives.

Table 2-4 presents these three components of the learning objective, with questions to ask yourself and guidelines for creating the learning objective statement.

Table 2-3. Learning objectives quiz.

For each learning objective given below, circle the performance condition and mark “PC.” Then circle and mark (“PS”) the performance statement. And then circle and mark (“PCR”) the performance criterion. |

1. Given the guidelines for effective problem solving and three case studies containing performance problems, analyze the situations and write three alternative solutions for each according to the guidelines. |

2. Given repair tools, maintenance procedures, and a broken laser printer, repair the printer until the printouts are aligned properly, in focus, and in two colors. |

3. Given the company’s mission statement, its guidelines for effective customer service, and five videotaped situations, view the video and respond to the customer according to the company’s standards for customer service. |

4. Given the guidelines for menu building around dietary requirements, plan a week of menus for the following patients on special diets. |

Table 2-4. Guidelines for writing learning objectives.

The Levels of Learning Execution

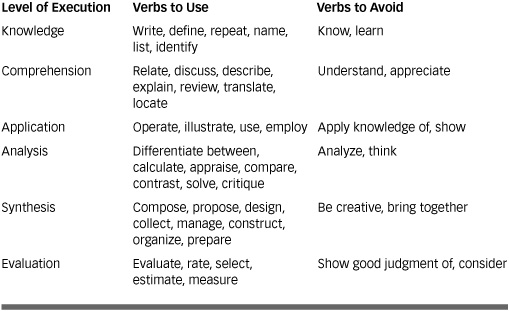

Training generally attempts to meet two types of educational goals: knowledge and application. When you write a learning objective, keep in mind that there are six levels of execution, as shown in Table 2-5. For example, your training may present a new policy (knowledge) or procedure (comprehension) that learners must know how to use (application) to review a claim (analysis).

Review Table 2-5 to choose an appropriate verb for the objective statement you intend; for example, for the Knowledge level, choose a verb such as identify. Table 2-5 also lists verbs to avoid, like understand or know, because they describe a learner’s internal state, which cannot be observed. The learning objective should always be a well-defined behavioral outcome statement.

Table 2-5. Levels of learning objectives and their corresponding vocabulary.

Once the objective is defined, it serves as the blueprint for designing the course and modules, as well as the supporting facilitator and participant manuals.

Validating the Learning Objectives

Once the learning objective is stated, you can use the following questions to validate that objective, making sure that the statement is clearly written, doable, and measurable:

1. Who is to perform the task?

2. What type of learning is involved?

3. What is the terminal behavior?

4. Under what conditions will the task be demonstrated?

For each objective, there should be documentation elaborating the following:

![]() Special teaching points

Special teaching points

![]() Instructional methods to be used

Instructional methods to be used

![]() Media requirements

Media requirements

![]() Testing requirements

Testing requirements

The Course Outline

The training sequence is best developed in a logical order. The usual sequence is to use step-by-step, or simple-to-complex, or to give an overview of the training concepts and then drill down to each element. When it’s appropriate for learners to know how a complex system or process works before you present the details, provide an overview so that the learners can create a mental model of the topic being presented before approaching its component concepts.

Once you decide on a design strategy, the first step is to make general decisions about the training methods. One simple way to choose an instructional method is to ask whether the course will include on-the-job training, classroom instruction, lab or workshop instruction, or self-instruction. Likewise, ask whether the course will use textbooks, consumable workbooks, computers, or interactive CDs or DVDs. The instructional method that you select must match the stated learning objectives for the course. For example, the strategies for a course to help learners master a computer skill should not rely heavily on pencil-and-paper activities.

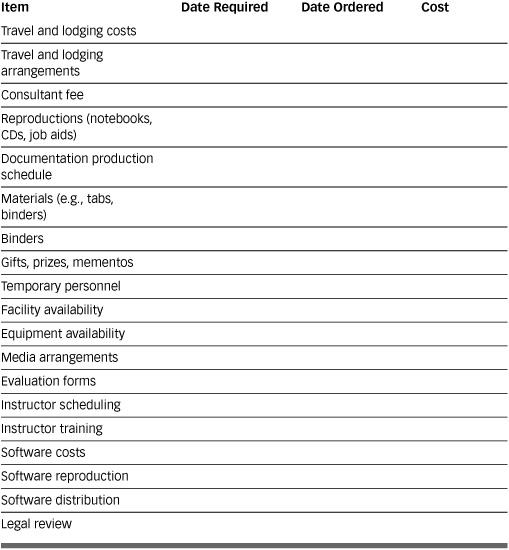

Support requirements include materials, equipment, and administrative support, such as computers, chart paper, and wall charts. It is critical to identify the support requirements to ensure that they will be available when you need them. When you have the learning objectives well stated and your media requirements itemized, you can estimate the support resources you’ll need and the number of days for the training by using the checklist in Table 2-6. The list identifies some typical items necessary for running a training program. Itemized lists like this can help you ensure that all of the support personnel and materials have been arranged for the programs.

The second step in developing your instructional map of the training is to design content test items to be used during the training as a way of checking on the learning process. Well-written learning objectives will specify that the learner demonstrate observable and measurable actions. The criterion test is another part of the blueprint that will help you develop the course. A criterion test allows you to translate the test score into a statement describing the behavior to be expected of a person with that score or his or her relationship to the specified subject matter. Most tests given by schoolteachers are criterion tests. The objective is simply to see whether or not the student has learned the material. Criterion-referenced assessments can be contrasted with norm-referenced assessments.

If the course is long enough to warrant intermediate mastery tests, you should specify the behaviors to be measured at each checkpoint, along with determining the format of the test. Place whatever format you select for the blueprint in a reference binder for subsequent use by the following people:

Table 2-6. Support requirements checklist.

![]() Course developer and suppliers in specialized media

Course developer and suppliers in specialized media

![]() Instructor or facilitator to get an overview of the content of the course

Instructor or facilitator to get an overview of the content of the course

![]() Training department staff to counsel employees on which course to add to their professional/career development plan

Training department staff to counsel employees on which course to add to their professional/career development plan

![]() Managers to determine if a course contains specific material

Managers to determine if a course contains specific material

Test Items

Many times we think that, once the learning objectives are written, we can go right ahead and develop the training materials. Not so fast! There is one vital element that most instructional designers skip, yet it is a key factor in the process, and it’s best done after creating the learning-objective statement. This next vital step is to create the test items that will ensure that the objective performance is the same as the performance to be assessed.

Well-designed test items are important because they indicate whether the learning objective has been reached. Think about the test item as a mirror image of the learning objective. The only difference is the verb: the learning objective is expressed in the future tense, while the test item is expressed in the present tense. So, write test items that correspond to the following learning objectives:

![]() Use the same resources and tools as stated in the condition component of the learning objective.

Use the same resources and tools as stated in the condition component of the learning objective.

![]() Get the learner to complete the action stated in the performance component of the learning objective.

Get the learner to complete the action stated in the performance component of the learning objective.

![]() Measure success as stated in the criterion component of the learning objective.

Measure success as stated in the criterion component of the learning objective.

Here is an example of a test item that fits the learning objective:

OBJECTIVE: Given 10 lenses of unknown quality, a magnifying glass, and the lens defect-detection tool, the learner inspects the lenses for defects and separates acceptable lenses from unacceptable lenses, with no more than two errors.

TEST ITEM: Here are 10 lenses from molding machine number 4. Use your magnifying glass and the corporate lens-defect reference card to pick out the defective lenses. Put all acceptable lenses in pile A. Return defective lenses to Operations. You may not have more than two mistakes. In this case, the test item accurately measures the objective.

Here is an example of a test item that does not fit the learning objective:

OBJECTIVE: Given skills practice (role-plays) that deal with customer objections and guidelines for overcoming objections, the learner role-plays overcoming customer objections with the course instructor until the objections are taken care of according to class guidelines and the instructor’s requirements.

TEST ITEM: In your participant packet, there are three skills practice (role-play) situations whereby you must close the sale with the customer. While your instructor plays the role of the customer, you assume the role of the salesperson and close the sale according to the guidelines and the instructor’s feedback.

(Note: This test item doesn’t measure whether the trainee has learned to overcome objections because the test item asks the trainee to close the sale.)

The Course Map and Structure

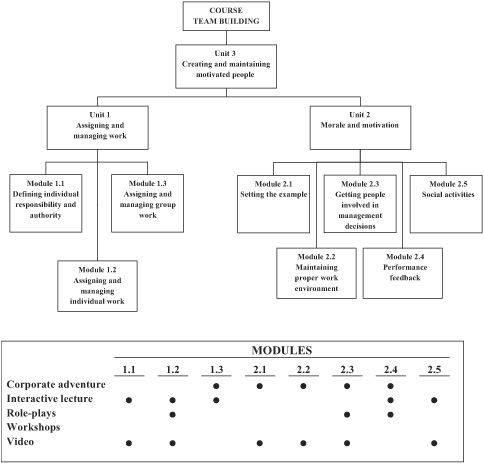

Having completed the task analysis, written the objectives, and designed the test items, you now have a good idea of what is going to be included in the training. The next step is to outline the information you plan to present and develop the course map. It is critical to keep your audience and the purpose of the course in mind. The course map, a sample of which is shown in Figure 2-3, lists in hierarchical order the modules within the units. Some trainers describe the hierarchy as modules within chapters or as units within lessons within modules. The terminology is not important.

The course map is paired with your media selections and support requirements, as shown below the course map in Figure 2-3. You should think about these resources as you design your course map and ensure that the design is consistent with the following:

![]() Course objectives

Course objectives

![]() Class size

Class size

![]() Training site

Training site

![]() Pre- and post-coursework

Pre- and post-coursework

It is important to consider the big picture when you develop a course, especially keeping in mind the reasons for the course, as you develop a course sequence. Here are some guidelines for sequencing the course:

![]() Focus on what happens on the job.

Focus on what happens on the job.

![]() Use the job analysis to establish the sequence of chapters.

Use the job analysis to establish the sequence of chapters.

![]() Arrange the course from general to specific or simple to complex.

Arrange the course from general to specific or simple to complex.

Figure 2-3. Sample course map.

![]() When there is no job-related basis for sequencing, arrange the course in the most logical fashion for the learner.

When there is no job-related basis for sequencing, arrange the course in the most logical fashion for the learner.

![]() If a performance model is available, use it as a guide for sequencing the content.

If a performance model is available, use it as a guide for sequencing the content.

![]() Use the same training advisory group to test the content sequence as you did to validate other areas of your analysis and design process.

Use the same training advisory group to test the content sequence as you did to validate other areas of your analysis and design process.

You have the objective statement and the test item, so you are ready to structure your training. Structuring your program is easy because it is just a matter of listing your course topics and subtopics and organizing the methods and activities. But let’s begin with the lowest level of the course map: the lesson.

Lessons, to Modules, to Units

Designing and developing a training program is just like any other project you take on, and success comes with careful planning and preparation. You’ve come to the most crucial part of the design: structuring the series of lessons. In this top-down format, the lesson is the microcosm of information about the task and knowledge to be learned. It has a specific format and specific criteria.

Why start with the lesson? Because adult learners respond best to small, organized components of learning. Lessons become the building blocks of modules, which then become the building blocks of units. No matter what delivery method or medium you use, the lesson is your foundation.

What is the purpose of a lesson? Because each lesson relates to a specific task listed in the task analysis, the lesson provides the content and practice to allow the learner to perform that task at the end of the training.

Guidelines for Constructing Lessons

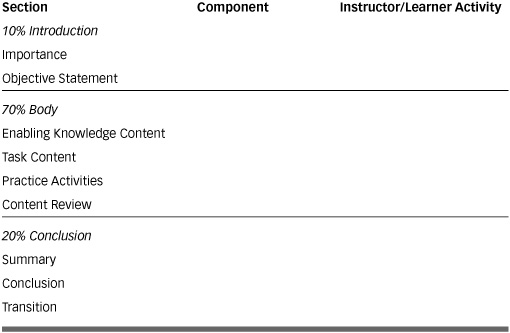

You can easily convert your task-analysis information into topical lessons. Table 2-7 shows the lesson structure as 10 percent introduction, 70 percent body of information, and 20 percent conclusion.

In addition to the content in a lesson, learning methods ensure that learners meet the learning objectives. You can use a variety of learning methods to stimulate learning and make training a learner-centered event. Ask yourself, “What is the purpose of this training, and how would I like to learn the topic, if I were the learner?” When you put yourself in the learner’s shoes, you can build a training lesson that is probably more direct and employs more interactive training methods.

Table 2-7. Lesson structure worksheet

Likewise, there are many formats for a lesson plan; most lesson plans contain some or all of the following elements, typically in this order:

![]() Title of the lesson

Title of the lesson

![]() Time required to complete the lesson

Time required to complete the lesson

![]() List of required materials

List of required materials

![]() List of objectives, which may be behavior-based (what the learner can do at lesson completion) or knowledge-based (what learners should know at lesson completion)

List of objectives, which may be behavior-based (what the learner can do at lesson completion) or knowledge-based (what learners should know at lesson completion)

![]() The set (or lead-in, or bridge-in) that focuses the learner on the lesson’s skills or concepts—these include showing pictures or models, asking leading questions, or reviewing previous lessons

The set (or lead-in, or bridge-in) that focuses the learner on the lesson’s skills or concepts—these include showing pictures or models, asking leading questions, or reviewing previous lessons

![]() An instructional component that describes the sequence of events that make up the lesson, including the facilitator’s instructional input and guided practice the learner uses to try new skills or work with new ideas

An instructional component that describes the sequence of events that make up the lesson, including the facilitator’s instructional input and guided practice the learner uses to try new skills or work with new ideas

![]() Independent practice that allows learners to extend skills or knowledge on their own

Independent practice that allows learners to extend skills or knowledge on their own

![]() A summary, whereby the facilitator wraps up the discussion-and-answer questions

A summary, whereby the facilitator wraps up the discussion-and-answer questions

![]() An evaluation, or a test for mastery of the instructed skills or concepts, such as a set of questions to answer or an instruction to follow

An evaluation, or a test for mastery of the instructed skills or concepts, such as a set of questions to answer or an instruction to follow

![]() An analysis, which the facilitator uses to reflect on the lesson itself, such as what worked

An analysis, which the facilitator uses to reflect on the lesson itself, such as what worked

![]() A continuity component, allowing learners to review and reflect on the content from the previous lesson

A continuity component, allowing learners to review and reflect on the content from the previous lesson

A well-written lesson plan reflects the interests and learning needs of the learners, as well as incorporates the best practices for the industry. The lesson reflects your teaching philosophy, which is your purpose in presenting this information. When you write the lesson plan, consider the elements of your initial design report and how you had divided the topics and subtopics to be covered. Eventually you will integrate the lesson plan into the instructor’s guide that you will create after you have completed designing and developing the training components, learner materials, and instructional coursework.

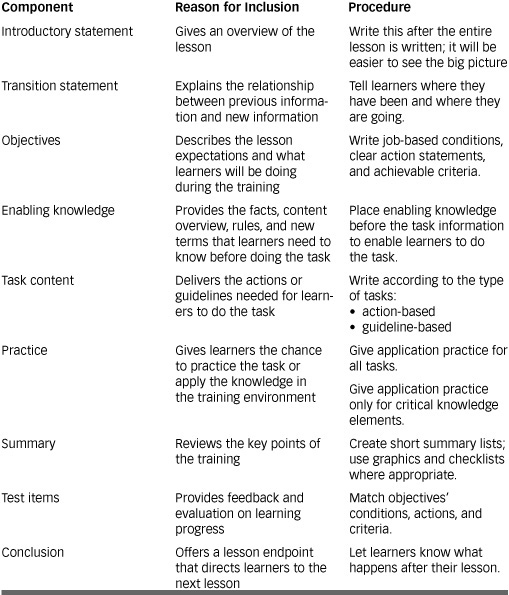

Table 2-8. Profile of lesson design.

The profile of the lesson design, shown in Table 2-8, is a blueprint to follow in laying out your materials for each lesson. As the table shows, you consider the development and flow, the content, and the delivery in terms of the stages in the lesson. Specifically, a lesson plan breaks down into several components, as listed in Table 2-9. For each component, you must know both the reason you include the component in the lesson and the guidelines for developing that component, as shown in the table. Between the introductory and summary components of the lesson plan, three “content” components provide the bulk of the lesson, and they are the most time-consuming to develop.

Table 2-9. Components of a lesson.

Consider each of the following tips as you write the lessons for your training program:

1. Timing. List the time you will spend on each topic and subtopic of each lesson. A typical training day is six hours, and you have 55 minutes in an hour for training. You should allocate at least 10 percent of the time to introduce or make a transition to the topic, 70 percent of the time to deliver the content (which might include preparing the learners to learn, presenting the material, and practicing using the material with an exercise and feedback). The final 20 percent of the time should be devoted to summary, conclusion, and transition to the next lesson or module.

2. Content. List the topics and subtopics that you will cover during each lesson. Do not combine lessons. Develop and deliver each lesson topic independently, using transitional statements to bridge from one topic or subtopic to another. In the lesson plan, indicate your introductions, breaks, and sequences in one lesson. Don’t have run-on sessions without using transition statements. (Run-on sessions are those that continue without using transition statements and might not be similar in content or practice.) Deliver the content in complete and inclusive parts. Illogical breaks that occur because you did not scope the content appropriately will leave the learning session in an awkward state and the learners will feel that the training is incomplete.

3. Training Techniques. Explain whether the session is to be a lecture, show and tell, or participant discovery.

4. Learner Activity. List the types of things that learners will be doing during the lesson (listening, looking, practicing). By documenting this information, you’ll have the opportunity to build a variety of activities into your training.

5. Training Aids. List the instructional aids and strategies or peripherals that you’ll use and the order in which you’ll use them.

Remember, too much information at one time creates confusion. Chunking is the term used to describe breaking down concepts into meaningful parts. Give learners a maximum of three large pieces of information. If you have three major components to a topic, deliver them within an hour. Once you deliver the three large chunks, summarize and break. Similarly, cluster the topics into organized sections, such as introduction, body, and activities. Grade the content presentation to target the correct amount of information to deliver.

A lesson plan gives you the advantage of determining in advance if your delivery sequence is correct, if the content is relevant, and if your instructional strategies are appropriate. The lesson plan also is a resource checklist, an aid for you in preparing the auxiliary materials required for the lesson, such as handouts, videotapes, DVDs, CDs, or wall charts.

Note: Do not make your lesson plan too complicated. It is a road map to help you organize your course and stay with your objectives.

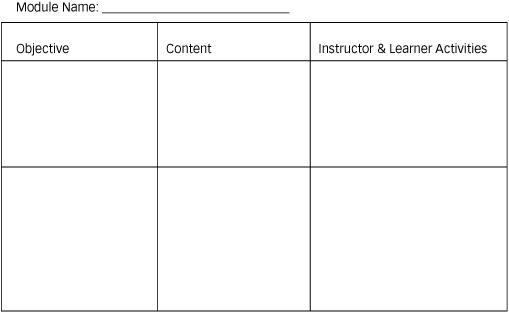

Guidelines for Constructing Modules

Lessons get grouped into modules. The module design, a sample of which is shown in Figure 2-4, brings a series of lessons together into a major section of what ultimately is a unit. The module is your course blueprint for further developing the content and instructional strategies of the training program. Make sure that, for each module in your program, you state the objective and identify the content topic.

Think of modules as containers for your lessons. The task analysis you did previously shows what tasks belong with each function. Now, you just decide in what order your lessons will fit into the modules and how the module relates to a specific task in the task analysis. There are several advantages to using a modular structure:

Figure 2-4. Sample module design.

![]() Key modules can be developed first to speed up the training time.

Key modules can be developed first to speed up the training time.

![]() Participants can sign up to take specific modules, based on personal need.

Participants can sign up to take specific modules, based on personal need.

![]() Sequence of training can be easily rearranged according to audience need.

Sequence of training can be easily rearranged according to audience need.

![]() Each section of the training is organized the same way to ensure consistency.

Each section of the training is organized the same way to ensure consistency.

Here are the major elements of a module:

![]() Objectives

Objectives

![]() Knowledge content to enable the learners to complete the task

Knowledge content to enable the learners to complete the task

![]() Task content

Task content

![]() Practice activities to help reach the objectives

Practice activities to help reach the objectives

![]() Assessment mechanism, such as test items, to determine if the objectives were achieved

Assessment mechanism, such as test items, to determine if the objectives were achieved

Other factors to take into account when creating a module include the best method for getting the objectives met, the timing and breaks, the amount of material to cover, the class or group size for activities, and any simulation of job conditions. Some tips for sequencing multiple lessons within a module are as follows:

![]() Use your task analysis to establish the sequence.

Use your task analysis to establish the sequence.

![]() Present enabling knowledge first to prepare for the task.

Present enabling knowledge first to prepare for the task.

![]() Use the same advisors to test the sequence as you did to validate other areas of needs analysis and design steps.

Use the same advisors to test the sequence as you did to validate other areas of needs analysis and design steps.

Some Overall Considerations

Design principles can provide a framework for organizing your learning materials. This framework then directs the flow of material and determines the activities so that you can decide which learning methods to use. For example:

![]() Learner directed. If the learners understand why they need the information you will give them, the lessons will be easier for them to learn; in this case, structure a lot of involvement and activities.

Learner directed. If the learners understand why they need the information you will give them, the lessons will be easier for them to learn; in this case, structure a lot of involvement and activities.

![]() Experiential. Learners gain more from experiencing the concepts being taught than from lectures or presentations. They want active involvement and relevance to their job and organization. So include practice and applying the concepts rather than strictly lectures.

Experiential. Learners gain more from experiencing the concepts being taught than from lectures or presentations. They want active involvement and relevance to their job and organization. So include practice and applying the concepts rather than strictly lectures.

![]() Able to be evaluated. When teaching a concept, define it. Specify as clearly as possible the result you want from the learners. Identify what changes in knowledge, skill, or attitude will take place as a result of the training.

Able to be evaluated. When teaching a concept, define it. Specify as clearly as possible the result you want from the learners. Identify what changes in knowledge, skill, or attitude will take place as a result of the training.

![]() Residual. Adults learn more effectively if they build on known information, facts, or experiences rather than from independent, arbitrary facts. Provide information that builds on their experience and knowledge, and leads them into deeper knowledge.

Residual. Adults learn more effectively if they build on known information, facts, or experiences rather than from independent, arbitrary facts. Provide information that builds on their experience and knowledge, and leads them into deeper knowledge.

![]() Numerous instructional methods. People vary in how they learn best. Incorporate various instructional methods into your lessons.

Numerous instructional methods. People vary in how they learn best. Incorporate various instructional methods into your lessons.

An Example: A Course for New Managers

Drew has to develop a problem-solving and decision-making course for new managers at this company. After completing a thorough task analysis, he uses the guidelines for course structure and the sample course map to develop a graphic representation of the job functions and tasks. He then translates those functions and tasks into a full-scale course with units and modules. Remember, the job function translates into a unit and the job tasks translate into lessons making up the modules. To begin, Drew organized his elements into a logical framework and then developed subtopics, as shown in Figure 2-5.

The Design Report

Earlier, in connection with writing the lesson plan, a “design report” was mentioned. The design report is a summary of the analysis and program design completed to date. It serves as a preliminary communiqué to inform management of your progress, and it provides an opportunity for receiving their suggestions and feedback on the plan. It is a way to ensure that your training meets management’s expectations, as management support for the course objectives is critical to your success, as well as the success of your program and the learners. The report serves to inform management of the proposed training. It also provides a road map for the instructional designer to use in developing the training. And it offers the instructor the necessary information on how and why the training was developed.

Figure 2-5. Drew’s management training course.

Unit 1: Problem Analysis

Module 1: How to state the problem

Module 2: How to define the standard

Module 3: How to define the differences

Unit 2: Cause Identification

Module 1: How to determine training deficiencies

Module 2: How to determine other deficiencies

Unit 3: Data Collection

Module 1: How to create data-collection questions

Module 2: How to use data-collection sources

Module 3: How to manage data collection

Unit 4: Idea Generation

Module 1: How to use individual techniques

Module 2: How to use group techniques

Unit 5: Solution Selection

Module 1: How to evaluate ideas

Module 2: How to select best ideas

Unit 6: Solution Implementation

Module 1: How to manage resources

Module 2: How to complete a time and action plan

Unit 7: Solution Evaluation

Module 1: How to measure effect of solution

Module 2: How to document results

A design report contains seven narrative components:

1. Purpose of the course

2. Summary of the analyses

3. Scope of the course

4. Test item strategy

5. Course and module design

6. Delivery strategy

7. Level of evaluation to be tested

In the last section, the example of a management training course was introduced. Here, Figure 2-6 shows a sample design report for a similar problem-solving course for new managers. In the design report, the following elements are discussed: purpose, summary of analyses, scope, objectives, test items, delivery format, and evaluation.

Figure 2-6. Problem-solving course for new managers.

Purpose of Course

The course will introduce new managers to the established problem-solving strategies developed at our company. These problem-solving skills will be separated into several training sessions. The course will be designed to integrate current company problems, rather than use problems discussed when the course was last held five years ago.

Summary of Analyses

Needs analysis and problem analysis: When the course was last taught, these analyses led to the development of an internal problem-solving model for use during management sessions. That model was successful, but it needs updating.

Audience analysis: The company has 30 managers located in eight regions who need to learn the problem-solving model to participate more effectively in management meetings.

Job and task analysis: The problem-solving model already exists. We need to customize it to meet the new managers’ needs and overcome questions about our new product line. Attached is our survey of their needs.

Scope of the Course

This course will use a seven-stage model of problem solving. The three-day course will be held at our corporate headquarters. All new managers will attend.

Task Learning Objectives

Objective 1: Given the problem-solving model and one case-study scenario, resolve the customer question to the level of satisfaction of the instruction.

Objective 2: Given the product features guidelines and the problem-solving model, resolve the customer product complaint to the satisfaction of the customer within acceptable guidelines of the company policy.

Objective 3: List and define the steps in the problem-solving model.

Test Item Strategy

The learners will have to demonstrate mastery of the problem-solving model by using all seven stages of the model in two case studies in the workshop. They will be assessed at the end of each chapter.

Delivery Strategy

This course will be an instructor-led, three-day classroom training. The instructor team will include a member of the training staff and an experienced company manager. The course will be held at corporate headquarters.

Evaluation Stages Measured

• Stage 1: Learner Reaction. Daily classroom reaction sheet.

• Stage 2: Learning. Test items will measure learning.

• Stage 3: Behavior. Surveys will go out to all management before and after training to assess changes in managerial problem solving.

The Enabling-Knowledge Bull’s Eye

As stressed earlier, the “must know” information to be included in the training program is the enabling knowledge that gives the learner the ability to perform the task or job. The “need to know” information is the background knowledge in order for the learner to understand that “must know” information. The “nice to know” information includes what is not necessary for the learner to know but could be helpful in better grasping the points covered in the session.

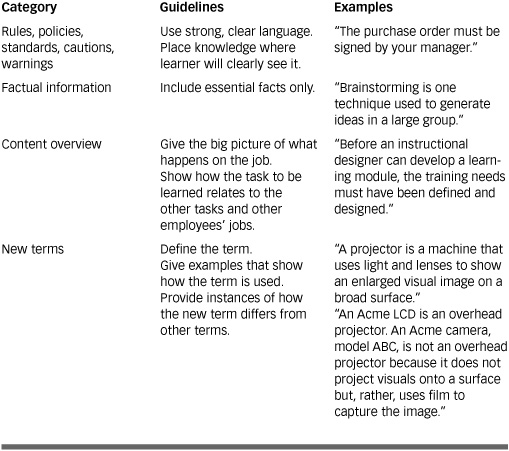

It’s reasonable to assume that if you aim your training program at the bull’s eye—the “must know” area—you will also spend time hitting the “need to know” area as a review. If time permits, you can spread the aim wider yet, hitting the “nice to know” area. However, it is likely the time would probably be better spent reviewing the “need to know” and “must know” areas. It is better to deliver too little well rather than too much badly. Use the guidelines in Table 2-10 to focus your eye on delivering the enabling knowledge.

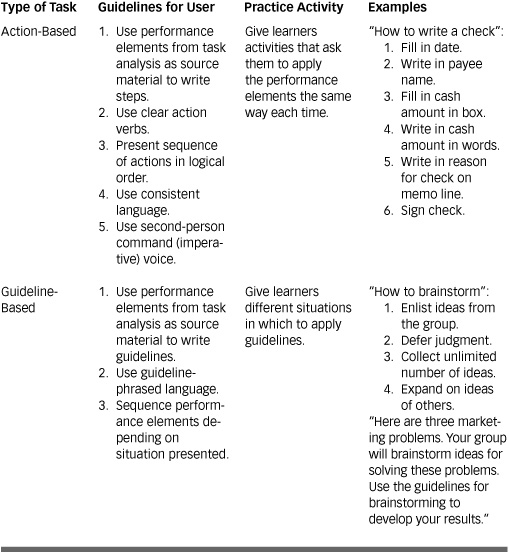

Action-based and Guideline-based Task Information

Action-based tasks are derived from the task analysis. Guideline-based tasks also originate from the task analysis, but the sequential format is not required, as it is for the action-based tasks. Use the guidelines in Table 2-11 to write your action-based and guideline-based task information and practices.

Teaching Methods

You have defined the learning objectives and organized the course as a series of units composed of modules, which are themselves composed of lessons. You have also submitted your design report and received feedback. Now you need to decide on your teaching methods.

Table 2-10. Guidelines for delivering enabling knowledge.

At this point, it would be worthwhile to compare your plans to the teaching methods template shown in Table 2-12. This template pairs the training objectives with the methods and setting, such as individual or group involvement. Following that, you can consider the various materials and methods available to you.

Table 2-11. Action-based and guideline-based tasks.

Table 2-12. Teaching methods template.

Training Materials for the Learners

Training materials must support course objectives. Available resources may include ready-made materials chosen for a specific course, customized materials designed for a specific course or module, materials taken from a previous course developed in-house, or new materials purchased from outside vendors.

![]() Off-the-Shelf Materials. Commercially prepared training materials save you and the company development time; however, their topics or content are generic, which means they may not fit exactly with your specific situation. That is, you may need to make some adjustments. If you need the material to be client focused, then you’ll have to spend time and resources customizing the off-the-shelf program.

Off-the-Shelf Materials. Commercially prepared training materials save you and the company development time; however, their topics or content are generic, which means they may not fit exactly with your specific situation. That is, you may need to make some adjustments. If you need the material to be client focused, then you’ll have to spend time and resources customizing the off-the-shelf program.

![]() Custom-Made Materials. Creating materials in your company will take longer than if you simply purchase off-the-shelf products. Custom-made materials usually also are more expensive because they must be made from scratch. However, once created, custom-made materials can be repurposed because your company owns the copyright on them.

Custom-Made Materials. Creating materials in your company will take longer than if you simply purchase off-the-shelf products. Custom-made materials usually also are more expensive because they must be made from scratch. However, once created, custom-made materials can be repurposed because your company owns the copyright on them.

Matters of Copyright

Bear in mind when developing course materials that copyright laws protect intellectual rights and creative efforts. Trainers try to use the very latest materials, but they must guard against using anything done by someone else without obtaining permission. Copyright, as defined by SHRM guidelines, is “the exclusive right or privilege of the author or proprietor to print or otherwise multiply, distribute, and vend copies of his/her literary, article, or intellectual products when secured by compliance with the copyright statute.”1 The Copyright Act of 1976 stipulates that copyright begins with the creation of the work in a fixed form from which it can be perceived or communicated. SHRM points out that registration of the copyright with the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress is not a condition of copyright; the law does, however, provide inducement to register work. The exclusive rights of the author or proprietor are limited by the fair use of copyrighted works in certain circumstances, but whether a use is fair depends on several factors, including its purpose, nature, amount, and effect on potential market value.

“Fair use” standards may apply to training materials. As a trainer, you can make a single copy of copyrighted materials for your own use, but check with the copyright holder before you make multiple copies. As SHRM points out, “if a trainer violates copyright statutes, the penalties can be severe and may include injunction, actual damages, defendant’s lot profits, statutory damages, and attorney’s fees.”

For anonymous works and works made for hire (such as those prepared by trainers or other employees at the request of employers), the period of protection lasts for 75 years, from the first year of publication, or 100 years from the year of creation, whichever expires first. Employers, rather than employees who did the writing, are considered the authors of the work and the owners of the copyright.

A work that has fallen into the public domain is available for use without permission from the copyright owner. A work is considered public domain if it meets one of the following characteristics:

![]() It was published prior to January 1, 1978, without notice of copyright.

It was published prior to January 1, 1978, without notice of copyright.

![]() The period of copyright protection has expired.

The period of copyright protection has expired.

![]() It was produced for the U.S. government by its officers or employees as part of their official duties.

It was produced for the U.S. government by its officers or employees as part of their official duties.

Until recently, copyrights had very little to do with the daily work of trainers. Intellectual property was easy to protect. However, with the advent of the Internet, it is easy for any computer user to copy, distribute, or publish virtually anything, even that which was written and belongs to someone else. Bear in mind that messages or articles posted on a Usenet newsgroup or e-mail are automatically copyrighted by the authors.

Assembling Your Resource Library

Keep a library of all the course materials you use or develop. It just might be that, on occasion, you can use a module from a previous source or can customize an in-house program to fit a new course. It is okay to do this. The course material belongs to your company, unless you have borrowed it from another company. In general, it’s better to have customized material in your library than the generic. You will have more control of the content and will understand the rationale behind the design of the training.

It is important to make sure that the teaching materials you use are accurate and will achieve the desired results. There is nothing worse for an instructor than to get to class and have the learners point out errors, find the material confusing, or be unable to follow the directions. Similarly, you need to validate older material you are using to be sure it is right for your new intended use.

Ways to validate the material include individual (one-on-one) tests conducted by the course designer; group tests (several learners in a segment of the course led by the course designer); or pilot tests (trial run by the course instructor). You should make any changes to the material after each validation. Conduct another validation after revisions have been made to ensure that your objectives will be achieved. Table 2-13 offers some guidelines for this type of validation.

Table 2-13. Guidelines for validating and revising training materials.

Participants to Watch | Data to Collect |

Learners | • Timing |

Instructor | • Timing |

Evaluation Materials

Because evaluation is a natural consequence of training, you will need to produce feedback forms for your learners. These forms should be easy to understand and require minimum time to complete. Make certain that the forms are complete in what they are surveying, otherwise you’ll get incomplete, possibly invalid, information. (Of course, once the evaluations are done, you will have to provide copies to the course developer, the course evaluator, and the course administrator.)

Each stakeholder reviews the evaluation differently and acts on the content. For example, the developer will look for remarks on topic treatment and instructional activities. The data then serve as the basis for course revisions. In the same manner, you’ll be keeping data on the learners and the program results. Training records can be kept in paper files or on a computer database. (To maintain good training records, try the commercial registrar or similar record-management systems.) The course administrator can be responsible for maintaining this database.

Training Materials for the Instructors

Now that you have compiled the learner materials, moving on to the instructor materials is easy. In many corporate training structures, the course designer is responsible for producing an instructor guide that tells the instructor what must be accomplished in the class. The individual instructors are then responsible for developing their own training aids. So the extent of the materials you need to provide varies with the situation.

In conducting a training program, most instructors use specific materials so as to provide consistency, standardization, quality control, and visual effect. The guidelines in Table 2-14 should be helpful in assembling the instructor materials and include a variety of visual aids.

Table 2-14. Guidelines for preparing instructor materials.

Type of Material | Guidelines |

Instructor guide | • Include expected outcomes/objectives |

Overhead visuals | • Use simple content |

Charts | • Write legibly |

Learning charts | • Use multiple colors |

The Legal Implications of Training

As you are developing a training program, you need to be aware of the legal ramifications of your situation. There are laws that require your ensuring that everyone involved has equal access to the training. Likewise, you need to be able to address any charges of discrimination.

Laws Against Job Discrimination

Since the 1960s, federal laws have required employers to provide equal opportunity in employment and career progression. All of these laws require employers to inform employees of their rights by posting copies of the laws themselves, related notices, and open positions in the company. You should be familiar with the following laws that affect training and professional development.

![]() Title VII, Civil Rights Act. Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to bring about equality in hiring, transfers, promotions, access to training, and other employment-related decisions. Title VII also stipulates that there must be equal opportunity to participate in trainings. If employees have nondiscriminatory access to the same training, everyone will have the opportunity to be better qualified for advancement.

Title VII, Civil Rights Act. Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to bring about equality in hiring, transfers, promotions, access to training, and other employment-related decisions. Title VII also stipulates that there must be equal opportunity to participate in trainings. If employees have nondiscriminatory access to the same training, everyone will have the opportunity to be better qualified for advancement.

![]() Age Discrimination in Employment Act. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) was enacted in 1967 to protect older workers. Generally, the ADEA protects workers over the age of 40 against employment discrimination on the basis of age. This protection includes giving qualified employees over 40 years of age equal access to training.

Age Discrimination in Employment Act. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) was enacted in 1967 to protect older workers. Generally, the ADEA protects workers over the age of 40 against employment discrimination on the basis of age. This protection includes giving qualified employees over 40 years of age equal access to training.

![]() Americans with Disabilities Act. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was modeled after the Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1974. People with either mental or physical disabilities or limitations, or who are regarded as having such impairments, sometimes suffer from employment discrimination in that they are not considered for jobs that they are qualified for and are capable of doing. The ADA protects qualified individuals from unlawful discrimination in the workplace, including access to training and career development.

Americans with Disabilities Act. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was modeled after the Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1974. People with either mental or physical disabilities or limitations, or who are regarded as having such impairments, sometimes suffer from employment discrimination in that they are not considered for jobs that they are qualified for and are capable of doing. The ADA protects qualified individuals from unlawful discrimination in the workplace, including access to training and career development.

![]() Labor Relations and Union Statutes. Union activity between the 1930s and the mid-1950s provided the impetus for the development and passage of two acts that affect training and professional development: The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA) and the Labor-Management Relations Act of 1947. The NLRA, also referred to as the Wagner Act, prohibits discrimination against union members with respect to terms and conditions of employment, including apprenticeships and trainings. The National Labor Relations Board considers training to be a condition of employment and a mandatory subject for collective bargaining.

Labor Relations and Union Statutes. Union activity between the 1930s and the mid-1950s provided the impetus for the development and passage of two acts that affect training and professional development: The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA) and the Labor-Management Relations Act of 1947. The NLRA, also referred to as the Wagner Act, prohibits discrimination against union members with respect to terms and conditions of employment, including apprenticeships and trainings. The National Labor Relations Board considers training to be a condition of employment and a mandatory subject for collective bargaining.

The Labor-Management Relations Act, also known as the Taft-Hartley Act, prevents unions from discriminating for any reason except for payment of dues and assessments. The act also permits noncoercive employer free speech. This may affect trainers; for example, if your company president supports a particular political party, it could be assumed that you support that party. In training, you should use no examples, case studies, or role plays that infringe upon a person’s personal philosophy or belief system.

Defense Against Charges of Training Discrimination

It is not difficult to defend yourself against a charge of training discrimination if you can show that your programs are designed and delivered without bias. The following guidelines apply to all of the employment laws discussed so far:

![]() Register affirmative action training and apprenticeship programs with the U.S. Department of Labor.

Register affirmative action training and apprenticeship programs with the U.S. Department of Labor.

![]() Keep records of all employees who apply for enrollment in training and the details of how they were selected.

Keep records of all employees who apply for enrollment in training and the details of how they were selected.

![]() Document all management decisions and actions that relate to the administration of training policies.

Document all management decisions and actions that relate to the administration of training policies.

![]() Monitor each trainee’s progress, provide evaluations, and ensure that counseling is available.

Monitor each trainee’s progress, provide evaluations, and ensure that counseling is available.

![]() Continue to evaluate results even after training is completed.

Continue to evaluate results even after training is completed.

Budget Matters

The goal of training and professional development in most organizations is to have a positive, cost-effective effect on the organization. Yet, the training department often appears as a departmental cost or organizational expense. Training provides a significant return on investment, and it can be viewed as such rather than as a line-item expense in the budget.

Using traditional cost-accounting principles, you can show a return when you cost out your training. To do this, you must calculate the total cost of the training. Next, you indicate the savings or benefit to the organization. Finally, you calculate the cost of the training per employee. Here’s the basic formula:

Total cost of training = cost per trainee ÷ number of people trained

The Training Costs Involved