ENGAGING LECTURE TIP 7

Logical Patterns

Communication is often most effective when it consists of a clearly organized set of ideas that follows a consistent and logical pattern. There are many different Logical Patterns, such as chronological order, cause-and-effect, spatial order, topical order, and so forth. Using a solid Logical Pattern to improve communication effectiveness is critical for lecturers and students. For lecturers, a solid structure provides a blueprint for the lecture, giving it focus and direction. For students, clear organization enhances the ease of understanding and remembering the information presented.

Lecture content should suggest a Logical Pattern that follows naturally. As Fink (2013) observes when talking about course organization more broadly: “The goal is to sequence the topics so that they build on one another in a way that allows students to integrate each new idea, topic, or theme with the preceding ones as the course proceeds” (p. 142). The same holds true for a given lecture; the Logical Pattern should enable lecture ideas to build on one another organically and move toward accomplishing an end goal.

There are no rules for choosing a pattern of organization. We describe some of the most commonly used patterns of organization in the following paragraphs.

Topical This pattern involves structuring content according to topic but in a nonlinear approach. You simply divide content into inherent chunks or clusters, similar to how we described in Tip 10: Sticky Note Diagrams. A lecture for teachers about types of children's games might be organized, for example, by different age groups:

- Preschoolers

- Elementary schoolchildren

- Secondary schoolchildren

Comparison and Contrast A comparison-and-contrast pattern involves organizing information according to how two or more things are similar to or different from each other. It is a useful pattern to adopt when describing how a topic in relation to another will improve student understanding. In particular, if students have knowledge of one topic, the teacher can compare or contrast it with a new topic to highlight similarities and differences. Following are two different approaches to organizing content by way of a comparison-and-contrast pattern.

| Example of Approach One | Example of Approach Two |

| Point 1 | Points of Comparison |

| Comparison | Point 1 |

| Contrast | Point 2 |

| Point 2 | Point 3 |

| Comparison | Points of Contrast |

| Contrast | Point 1 |

| Point 3 | Point 2 |

| Comparison | Point 3 |

| Contrast |

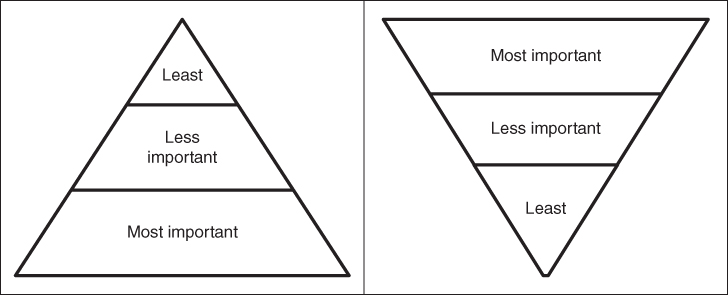

Order of Importance For this pattern, concepts and supporting ideas are organized according to a hierarchy of value. Information might be structured according to an ascending or descending order of importance as shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Order of Importance Example

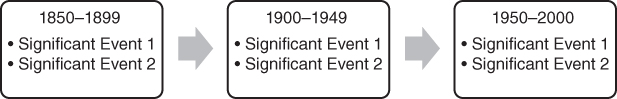

Chronological Order Information is organized by the time in which each event has occurred, as shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Chronological Order Example

Sequential Order Content is presented as a series of steps or actions that provides hooks for learners to remember. This pattern is often used when doing demonstrations. For example, a professor doing a lecture demonstration on how to draw blood would likely choose a sequential order, as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 Sequential Order Example

Cause and Effect When the content presents problems and solutions, a cause-and-effect structure can be a useful framework. This approach involves demonstrating important relations between variables and typically occurs in one of the two ways:

| Example of Approach One | Example of Approach Two |

| Causes | Cause 1 |

| Cause 1 | Effect 1 |

| Cause 2 | Effect 2 |

| Effects | Cause 2 |

| Effect 1 | Effect 1 |

| Effect 2 | Effect 2 |

Simple to Complex Instructional content might be organized from the simple to complex. The lecturer begins with information and ideas that are relatively easy for students to process and then gradually introduces more complex ideas or arguments. The ideas should build off of each other, and students have to listen their way through points A and B in order to understand point C. This strategy enables learners to build a knowledge base along with their confidence levels. It can also help to minimize learner frustration. For example, a professor offering a lecture on the human body might work through atoms, molecules, cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems as she leads up to the human organism.

Spatial Main points (especially places, scenes, or objects) are arranged by physical proximity or direction relative to each other. This might mean left to right, top to bottom, front to back, inside to outside, or clockwise. For example, a professor might describe a volcano from bottom to top, starting with magma, moving to bedrock, moving to the conduit, and so forth.

Problem and Solution The lecturer defines a problem and then offers information about a solution or solutions. When introducing problems, the lecturer provides different aspects and offers evidence of the problems. In the solution section, the lecturer not only presents potential solutions but also evidence to support the solutions. For example, a lecturer might introduce a problem on global warming, describing the various aspects of it and evidence to support that the problem exists. Then the lecturer might identify some potential solutions, such as boosting energy efficiency, promoting green energy, and managing forests.

Example

Key References and Resources

- Carnegie Mellon University, Eberly Center on Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation. (n.d.a). Design and teach a course. Retrieved from www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/design/contentschedule.html

- Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.