CHAPTER 11 Depreciation, Impairments, and Depletion

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the concept of depreciation.

- Identify the factors involved in the depreciation process.

- Compare activity, straight-line, and decreasing-charge methods of depreciation.

- Explain special depreciation methods.

- Explain the accounting issues related to asset impairment.

- Explain the accounting procedures for depletion of natural resources.

- Explain how to report and analyze property, plant, equipment, and natural resources.

Here Come the Write-Offs

The credit crisis starting in late 2008 affected many financial and nonfinancial institutions. Many of the statistics related to this crisis are sobering, as noted below.

- In October 2008, the FTSE 100 in the United Kingdom suffered its biggest one-day fall since October 1987. The index closed at its lowest level since October 2004.

- The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell below the 8,000 level for the first time since 2003.

- Germany's benchmark DAX tumbled after the collapse of the proposed rescue plan for Hypo Real Estate.

- Tightening credit and less disposable income led to Japanese electronic groups losing value. The Nikkei fell to its lowest point since February 2004.

- The Hong Kong Hang Seng dropped in line with the rest of Asia, closing below 17,000 points for the first time in two years in October 2008 and below 11,000 by November of that year.

- Governments spent billions of dollars bailing out financial institutions.

Although some financial rebound has occurred since October 2008, it is clear that most economies of the world are now in a slower growth pattern. This slowdown raises many questions related to the proper accounting for many long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment; intangible assets; and many types of financial assets. One of the most difficult issues relates to the possibility of higher impairment charges related to these assets and the related disclosures that may be needed. The following is an example of a recent impairment charge taken by Fujitsu Limited.

Impairment Losses (in part)

Due to the worsening of the global business environment, Fujitsu recognized consolidated impairment losses of 58.9 billion yen in relation to property, plant, and equipment of businesses with decreased profitability. The main losses are as follows:

(1) Property, Plant, and Equipment of LSI Business

Impairment losses related to the property, plant, and equipment of the LSI business of Fujitsu Microelectronics Limited totaled 49.9 billion yen. In January, Fujitsu Microelectronics announced business reforms in response to a sharp downturn in customer demand that began last autumn.

(2) Property, Plant, and Equipment of Optical Transmission Systems and Other Businesses

Consolidated impairment losses of 8.9 billion yen were recognized in relation to the property, plant, and equipment of the optical transmission systems business, the electronic components business and other businesses due to their decreased profitability.

(3) Property, Plant, and Equipment of HDD Business (included in business restructuring expenses)

Impairment losses of 16.2 billion yen have been recognized in relation to the property, plant, and equipment of the reorganized HDD business. These losses are included in business restructuring expenses. The impairment loss includes 5.3 billion yen recognized in the third quarter for the discontinuation of the HDD head business.

![]() CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

- See the Underlying Concepts on pages 592, 593, 594, and 601.

- Read the Evolving Issue on page 609 for a discussion of using the full-cost versus successful-efforts method for accounting for exploration costs.

![]() INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

- See the International Perspectives on pages 597, 602, 603, and 609.

- Read the IFRS Insights on pages 637–646 for a discussion of:

- Component depreciation

- Impairments

- Revaluations

Impairment losses for property, plant, and equipment for many companies in the next few years will be substantial. Here are some of the questions that will need to be addressed regarding possible impairments.

- How often should a company test for impairment?

- What are key impairment indicators?

- What disclosures are necessary for impairments?

- How do companies match their cash flows to the asset that is potentially impaired?

Assessing whether a company has impaired assets is difficult. For example, in addition to the technical accounting issues, the environment can change quickly. Reduced spending by consumers, lack of confidence in global economic decisions, and higher volatility in both stock and commodity markets are factors to consider. Nevertheless, for investors and creditors to have assurance that the amounts reported on the balance sheet for property, plant, and equipment are relevant and representationally faithful, appropriate impairment charges must be reported on a timely basis.

Source: A portion of this discussion is taken from “Top 10 Tips for Impairment Testing,” PricewaterhouseCoopers (December 2008).

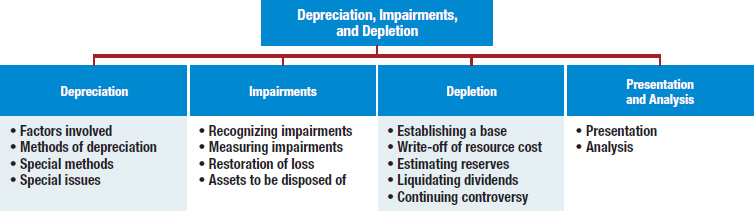

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 11

As noted in the opening story, both U.S. and foreign companies are affected by impairment rules. These rules recognize that when economic conditions deteriorate, companies may need to write off an asset's cost to indicate the decline in its usefulness. The purpose of this chapter is to examine the depreciation process and the methods of writing off the cost of property, plant, and equipment and natural resources. The content and organization of the chapter are as follows.

DEPRECIATION—A METHOD OF COST ALLOCATION

Most individuals at one time or another purchase and trade in an automobile. The automobile dealer and the buyer typically discuss what the trade-in value of the old car is. Also, they may talk about what the trade-in value of the new car will be in several years. In both cases, a decline in value is considered to be an example of depreciation.

To accountants, however, depreciation is not a matter of valuation. Rather, depreciation is a means of cost allocation. Depreciation is the accounting process of allocating the cost of tangible assets to expense in a systematic and rational manner to those periods expected to benefit from the use of the asset. For example, a company like Goodyear (one of the world's largest tire manufacturers) does not depreciate assets on the basis of a decline in their fair value. Instead, it depreciates through systematic charges to expense.

This approach is employed because the value of the asset may fluctuate between the time the asset is purchased and the time it is sold or junked. Attempts to measure these interim value changes have not been well received because values are difficult to measure objectively. Therefore, Goodyear charges the asset's cost to depreciation expense over its estimated life. It makes no attempt to value the asset at fair value between acquisition and disposition. Companies use the cost allocation approach because it recognizes the expense in the periods expected to benefit and because fluctuations in fair value are uncertain and difficult to measure.

When companies write off the cost of long-lived assets over a number of periods, they typically use the term depreciation. They use the term depletion to describe the reduction in the cost of natural resources (such as timber, gravel, oil, and coal) over a period of time. The expiration of intangible assets, such as patents or copyrights, is called amortization.

Factors Involved in the Depreciation Process

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Identify the factors involved in the depreciation process.

Before establishing a pattern of charges to revenue, a company must answer three basic questions:

- What depreciable base is to be used for the asset?

- What is the asset's useful life?

- What method of cost apportionment is best for this asset?

The answers to these questions involve combining several estimates into one single figure. Note the calculations assume perfect knowledge of the future, which is never attainable.

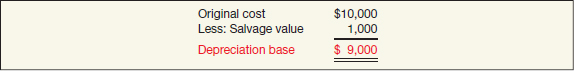

Depreciable Base for the Asset

The base established for depreciation is a function of two factors: the original cost, and salvage or disposal value. We discussed historical cost in Chapter 10. Salvage value is the estimated amount that a company will receive when it sells the asset or removes it from service. It is the amount to which a company writes down or depreciates the asset during its useful life. If an asset has a cost of $10,000 and a salvage value of $1,000, its depreciation base is $9,000.

From a practical standpoint, companies often assign a zero salvage value. Some long-lived assets, however, have substantial salvage values.

Estimation of Service Lives

The service life of an asset often differs from its physical life. A piece of machinery may be physically capable of producing a given product for many years beyond its service life. But a company may not use the equipment for all that time because the cost of producing the product in later years may be too high. For example, the old Slater cotton mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, is preserved in remarkable physical condition as an historic landmark in U.S. industrial development, although its service life was terminated many years ago.1

Companies retire assets for two reasons: physical factors (such as casualty or expiration of physical life) and economic factors (obsolescence). Physical factors are the wear and tear, decay, and casualties that make it difficult for the asset to perform indefinitely. These physical factors set the outside limit for the service life of an asset.

We can classify the economic or functional factors into three categories:

- Inadequacy results when an asset ceases to be useful to a company because the demands of the firm have changed. An example would be the need for a larger building to handle increased production. Although the old building may still be sound, it may have become inadequate for the company's purpose.

- Supersession is the replacement of one asset with another more efficient and economical asset. Examples would be the replacement of the mainframe computer with a PC network, or the replacement of the Boeing 767 with the Boeing 787.

- Obsolescence is the catchall for situations not involving inadequacy and supersession.

Because the distinction between these categories appears artificial, it is probably best to consider economic factors collectively instead of trying to make distinctions that are not clear-cut.

To illustrate the concepts of physical and economic factors, consider a new nuclear power plant. Which is more important in determining the useful life of a nuclear power plant—physical factors or economic factors? The limiting factors seem to be (1) ecological considerations, (2) competition from other power sources, and (3) safety concerns. Physical life does not appear to be the primary factor affecting useful life. Although the plant's physical life may be far from over, the plant may become obsolete in 10 years.

For a house, physical factors undoubtedly are more important than the economic or functional factors relative to useful life. Whenever the physical nature of the asset primarily determines useful life, maintenance plays an extremely vital role. The better the maintenance, the longer the life of the asset.2

In most cases, a company estimates the useful life of an asset based on its past experience with the same or similar assets. Others use sophisticated statistical methods to establish a useful life for accounting purposes. And in some cases, companies select arbitrary service lives. In a highly industrial economy such as that of the United States, where research and innovation are so prominent, technological factors have as much effect, if not more, on service lives of tangible plant assets as physical factors do.

What do the numbers mean? ALPHABET DUPE

Some companies try to imply that depreciation is not a cost. For example, in their press releases they will often make a bigger deal over earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (often referred to as EBITDA) than net income under GAAP. They like it because it “dresses up” their earnings numbers. Some on Wall Street buy this hype because they don't like the allocations that are required to determine net income. Some banks, without batting an eyelash, even let companies base their loan covenants on EBITDA.

For example, look at Premier Parks, which operates the Six Flags chain of amusement parks. Premier touts its EBITDA performance. But that number masks a big part of how the company operates—and how it spends its money. Premier argues that analysts should ignore depreciation for big-ticket items like roller coasters because the rides have a long life. Critics, however, say that the amusement industry has to spend as much as 50 percent of its EBITDA just to keep its rides and attractions current. Those expenses are not optional—let the rides get a little rusty, and ticket sales start to tail off. That means analysts really should view depreciation associated with the costs of maintaining the rides (or buying new ones) as an everyday expense. It also means investors in those companies should have strong stomachs.

What's the risk of trusting a fad accounting measure? Just look at one year's bankruptcy numbers. Of the 147 companies tracked by Moody's that defaulted on their debt, most borrowed money based on EBITDA performance. The bankers in those deals probably wish they had looked at a few other factors. On the other hand, nonfinancial companies in the S&P 500 generated a substantial EBITDA margin of 20.9 percent in 2011. Some analysts are concerned that such a high number suggests that companies are reluctant to incur costs and want to stockpile cash. The lesson? Investors will do well to avoid focus on any single accounting measure.

Sources: Adapted from Herb Greenberg, “Alphabet Dupe: Why EBITDA Falls Short,” Fortune (July 10, 2000), p. 240; and V. Monga, “Operating Efficiency Runs High at U.S. Firms,” Wall Street Journal (February 28, 2012), p. B7.

Methods of Depreciation

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Compare activity, straight-line, and decreasing-charge methods of depreciation.

The third factor involved in the depreciation process is the method of cost apportionment. The profession requires that the depreciation method employed be “systematic and rational.” Companies may use a number of depreciation methods, as follows.

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

Depreciation attempts to recognize the cost of an asset to the periods that benefit from the use of that asset.

- Activity method (units of use or production).

- Straight-line method.

- Decreasing-charge methods (accelerated):

(a) Sum-of-the-years'-digits.

(b) Declining-balance method.

- Special depreciation methods:

(a) Group and composite methods.

(b) Hybrid or combination methods.3

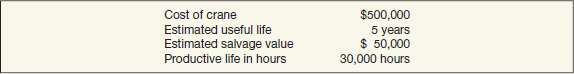

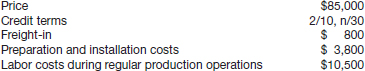

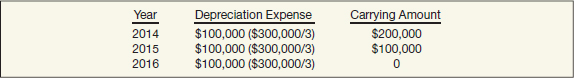

To illustrate these depreciation methods, assume that Stanley Coal Mines recently purchased an additional crane for digging purposes. Illustration 11-2 contains the pertinent data concerning this purchase.

Activity Method

The activity method (also called the variable-charge or units-of-production approach) assumes that depreciation is a function of use or productivity, instead of the passage of time. A company considers the life of the asset in terms of either the output it provides (units it produces) or an input measure such as the number of hours it works. Conceptually, the proper cost association relies on output instead of hours used, but often the output is not easily measurable. In such cases, an input measure such as machine hours is a more appropriate method of measuring the dollar amount of depreciation charges for a given accounting period.

The crane poses no particular depreciation problem. Stanley can measure the usage (hours) relatively easily. If Stanley uses the crane for 4,000 hours the first year, the depreciation charge is:

The major limitation of this method is that it is inappropriate in situations in which depreciation is a function of time instead of activity. For example, a building steadily deteriorates due to the elements (time) regardless of its use. In addition, where economic or functional factors affect an asset, independent of its use, the activity method loses much of its significance. For example, if a company is expanding rapidly, a particular building may soon become obsolete for its intended purposes. In both cases, activity is irrelevant. Another problem in using an activity method is the difficulty of estimating units of output or service hours received.

In cases where loss of services results from activity or productivity, the activity method does the best to record expenses in the same period as associated revenues. Companies that desire low depreciation during periods of low productivity, and high depreciation during high productivity, either adopt or switch to an activity method. In this way, a plant running at 40 percent of capacity generates 60 percent lower depreciation charges. Inland Steel, for example, switched to units-of-production depreciation at one time and reduced its losses by $43 million, or $1.20 per share.

Straight-Line Method

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

If benefits flow on a “straight-line” basis, then justification exists for recording the cost of the asset on a straight-line basis with these benefits.

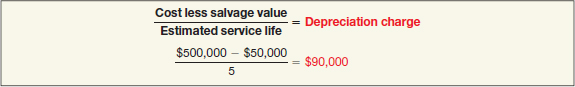

The straight-line method considers depreciation as a function of time rather than a function of usage. Companies widely use this method because of its simplicity. The straight-line procedure is often the most conceptually appropriate, too. When creeping obsolescence is the primary reason for a limited service life, the decline in usefulness may be constant from period to period. Stanley computes the depreciation charge for the crane as follows.

The major objection to the straight-line method is that it rests on two tenuous assumptions. (1) The asset's economic usefulness is the same each year, and (2) the maintenance and repair expense is essentially the same each period.

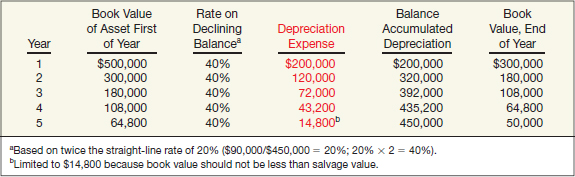

One additional problem that occurs in using straight-line—as well as some others—is that distortions in the rate of return analysis (income/assets) develop. Illustration 11-5 indicates how the rate of return increases, given constant revenue flows, because the asset's book value decreases.

Decreasing-Charge Methods

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

The expense recognition principle does not justify a constant charge to income. If the benefits from the asset decline as the asset ages, then a decreasing charge to income better matches cost to benefits.

The decreasing-charge methods provide for a higher depreciation cost in the earlier years and lower charges in later periods. Because these methods allow for higher early-year charges than in the straight-line method, they are often called accelerated depreciation methods.

What is the main justification for this approach? The rationale is that companies should charge more depreciation in earlier years because the asset is most productive in its earlier years. Furthermore, the accelerated methods provide a constant cost because the depreciation charge is lower in the later periods, at the time when the repair and maintenance costs are often higher. Generally, companies use one of two decreasing-charge methods: the sum-of-the-years'-digits method or the declining-balance method.

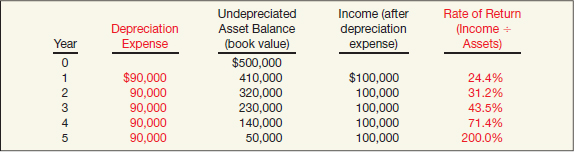

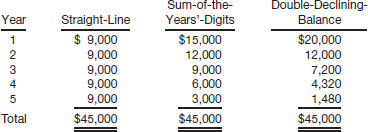

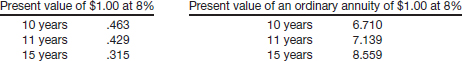

Sum-of-the-Years'-Digits. The sum-of-the-years'-digits method results in a decreasing depreciation charge based on a decreasing fraction of depreciable cost (original cost less salvage value). Each fraction uses the sum of the years as a denominator (5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 15). The numerator is the number of years of estimated life remaining as of the beginning of the year. In this method, the numerator decreases year by year, and the denominator remains constant (5/15, 4/15, 3/15, 2/15, and 1/15). At the end of the asset's useful life, the balance remaining should equal the salvage value. Illustration 11-6 shows this method of computation.4

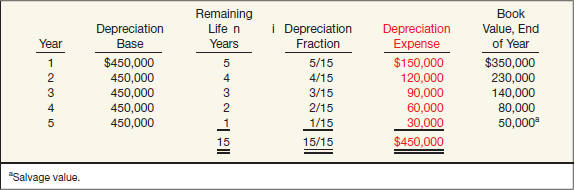

Declining-Balance Method. The declining-balance method utilizes a depreciation rate (expressed as a percentage) that is some multiple of the straight-line method. For example, the double-declining rate for a 10-year asset is 20 percent (double the straight-line rate, which is 1/10 or 10 percent). Companies apply the constant rate to the declining book value each year.

Unlike other methods, the declining-balance method does not deduct the salvage value in computing the depreciation base. The declining-balance rate is multiplied by the book value of the asset at the beginning of each period. Since the depreciation charge reduces the book value of the asset each period, applying the constant-declining-balance rate to a successively lower book value results in lower depreciation charges each year. This process continues until the book value of the asset equals its estimated salvage value. At that time, the company discontinues depreciation.

Companies use various multiples in practice. For example, the double-declining-balance method depreciates assets at twice (200 percent) the straight-line rate. Illustration 11-7 shows Stanley's depreciation charges if using the double-declining approach.

Companies often switch from the declining-balance method to the straight-line method near the end of the asset's useful life to ensure that they depreciate the asset only to its salvage value.5

Special Depreciation Methods

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain special depreciation methods.

Sometimes companies adopt special depreciation methods. Reasons for doing so might be that a company's assets have unique characteristics, or the nature of the industry. Two of these special methods are:

- Group and composite methods.

- Hybrid or combination methods.

Group and Composite Methods

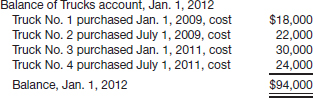

Companies often depreciate multiple-asset accounts using one rate. For example, AT&T might depreciate telephone poles, microwave systems, or switchboards by groups.

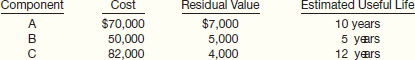

Two methods of depreciating multiple-asset accounts exist: the group method and the composite method. The choice of method depends on the nature of the assets involved. Companies frequently use the group method when the assets are similar in nature and have approximately the same useful lives. They use the composite approach when the assets are dissimilar and have different lives. The group method more closely approximates a single-unit cost procedure because the dispersion from the average is not as great. The computation for group or composite methods is essentially the same: find an average and depreciate on that basis.

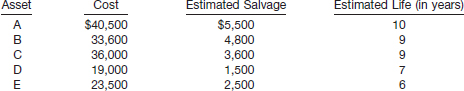

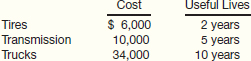

Companies determine the composite depreciation rate by dividing the depreciation per year by the total cost of the assets. To illustrate, Mooney Motors establishes the composite depreciation rate for its fleet of cars, trucks, and campers as shown in Illustration 11-8.

If there are no changes in the asset account, Mooney will depreciate the group of assets to the residual or salvage value at the rate of $56,000 ($224,000 × 25%) a year. As a result, it will take Mooney 3.39 years to depreciate these assets. The length of time it takes a company to depreciate its assets on a composite basis is called the composite life.

We can highlight the differences between the group or composite method and the single-unit depreciation method by looking at asset retirements. If Mooney retires an asset before or after the average service life of the group is reached, it buries the resulting gain or loss in the Accumulated Depreciation account. This practice is justified because Mooney will retire some assets before the average service life and others after the average life. For this reason, the debit to Accumulated Depreciation is the difference between original cost and cash received. Mooney does not record a gain or loss on disposition.

To illustrate, suppose that Mooney Motors sold one of the campers with a cost of $5,000 for $2,600 at the end of the third year. The entry is:

![]()

If Mooney purchases a new type of asset (mopeds, for example), it must compute a new depreciation rate and apply this rate in subsequent periods.

Illustration 11-9 presents a typical financial statement disclosure of the group depreciation method for Ampco-Pittsburgh Corporation.

The group or composite method simplifies the bookkeeping process and tends to average out errors caused by over- or underdepreciation. As a result, gains or losses on disposals of assets do not distort periodic income.

On the other hand, the unit method (depreciation of single assets) has several advantages over the group or composite methods. (1) It simplifies the computation mathematically. (2) It identifies gains and losses on disposal. (3) It isolates depreciation on idle equipment. (4) It represents the best estimate of the depreciation of each asset, not the result of averaging the cost over a longer period of time. As a consequence, companies generally use the unit method.6 Unless stated otherwise, you should use the unit method in homework problems.

Hybrid or Combination Methods

In addition to the depreciation methods already discussed, companies are free to develop their own special or tailor-made depreciation methods. GAAP requires only that the method result in the allocation of an asset's cost over the asset's life in a systematic and rational manner.

For example, the steel industry widely uses a hybrid depreciation method, called the production variable method, that is a combination straight-line/activity approach. The following note from WHX Corporation's annual report explains one variation of this method.

What do the numbers mean? DECELERATING DEPRECIATION

Which depreciation method should management select? Many believe that the method that best matches revenues with expenses should be used. For example, if revenues generated by the asset are constant over its useful life, select straight-line depreciation. On the other hand, if revenues are higher (or lower) at the beginning of the asset's life, then use a decreasing (or increasing) method. Thus, if a company can reliably estimate revenues from the asset, selecting a depreciation method that best matches costs with those revenues would seem to provide the most useful information to investors and creditors for assessing the future cash flows from the asset.

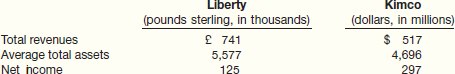

Managers in the real estate industry face a different challenge when considering depreciation choices. Real estate managers object to traditional depreciation methods because in their view, real estate often does not decline in value. In addition, because real estate is highly debt-financed, most real estate concerns report losses in earlier years of operations when the sum of depreciation and interest exceeds the revenue from the real estate project. As a result, real estate companies, like Kimco Realty, argue for some form of increasing-charge method of depreciation (lower depreciation at the beginning and higher depreciation at the end). With such a method, companies would report higher total assets and net income in the earlier years of the project.7

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

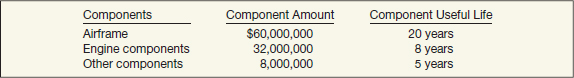

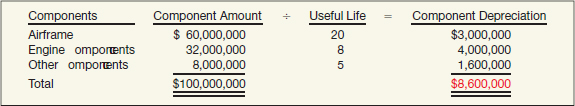

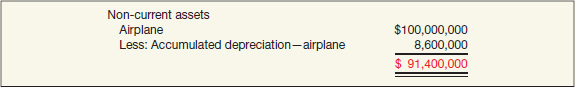

IFRS requires use of component depreciation.

Special Depreciation Issues

We still need to discuss several special issues related to depreciation:

- How should companies compute depreciation for partial periods?

- Does depreciation provide for the replacement of assets?

- How should companies handle revisions in depreciation rates?

Depreciation and Partial Periods

Companies seldom purchase plant assets on the first day of a fiscal period or dispose of them on the last day of a fiscal period. A practical question is: How much depreciation should a company charge for the partial periods involved?

In computing depreciation expense for partial periods, companies must determine the depreciation expense for the full year and then prorate this depreciation expense between the two periods involved. This process should continue throughout the useful life of the asset.

Assume, for example, that Steeltex Company purchases an automated drill machine with a five-year life for $45,000 (no salvage value) on June 10, 2013. The company's fiscal year ends December 31. Steeltex therefore charges depreciation for only 6⅔ months during that year. The total depreciation for a full year (assuming straight-line depreciation) is $9,000 ($45,000/5). The depreciation for the first, partial year is therefore:

![]()

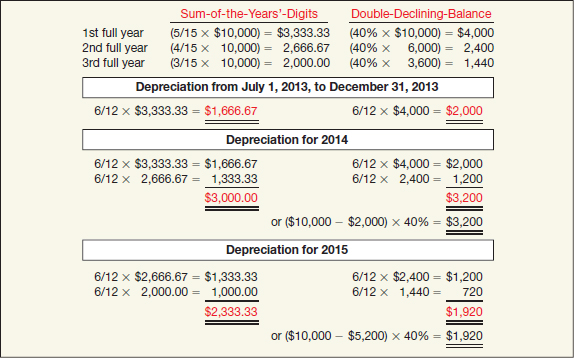

The partial-period calculation is relatively simple when Steeltex uses straight-line depreciation. But how is partial-period depreciation handled when it uses an accelerated method such as sum-of-the-years'-digits or double-declining-balance? As an illustration, assume that Steeltex purchased another machine for $10,000 on July 1, 2013, with an estimated useful life of five years and no salvage value. Illustration 11-11 shows the depreciation figures for 2013, 2014, and 2015.

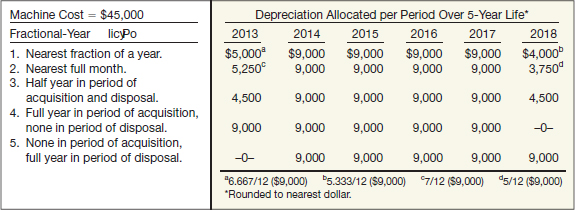

Sometimes a company like Steeltex modifies the process of allocating costs to a partial period to handle acquisitions and disposals of plant assets more simply. One variation is to take no depreciation in the year of acquisition and a full year's depreciation in the year of disposal. Other variations charge one-half year's depreciation both in the year of acquisition and in the year of disposal (referred to as the half-year convention), or charge a full year in the year of acquisition and none in the year of disposal.

In fact, Steeltex may adopt any one of these fractional-year policies in allocating cost to the first and last years of an asset's life so long as it applies the method consistently. However, unless otherwise stipulated, companies normally compute depreciation on the basis of the nearest full month.

Illustration 11-12 shows depreciation allocated under five different fractional-year policies using the straight-line method on the $45,000 automated drill machine purchased by Steeltex Company on June 10, 2013, discussed earlier.

Depreciation and Replacement of Property, Plant, and Equipment

A common misconception about depreciation is that it provides funds for the replacement of fixed assets. Depreciation is like other expenses in that it reduces net income. It differs, though, in that it does not involve a current cash outflow.

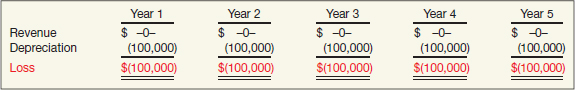

To illustrate why depreciation does not provide funds for replacement of plant assets, assume that a business starts operating with plant assets of $500,000 that have a useful life of five years. The company's balance sheet at the beginning of the period is:

![]()

If we assume that the company earns no revenue over the five years, the income statements are:

Total depreciation of the plant assets over the five years is $500,000. The balance sheet at the end of the five years therefore is:

![]()

This extreme example illustrates that depreciation in no way provides funds for the replacement of assets. The funds for the replacement of the assets come from the revenues (generated through use of the asset). Without the revenues, no income materializes and no cash inflow results.

Revision of Depreciation Rates

When purchasing a plant asset, companies carefully determine depreciation rates based on past experience with similar assets and other pertinent information. The provisions for depreciation are only estimates, however. Companies may need to revise them during the life of the asset. Unexpected physical deterioration or unforeseen obsolescence may decrease the estimated useful life of the asset. Improved maintenance procedures, revision of operating procedures, or similar developments may prolong the life of the asset beyond the expected period.8

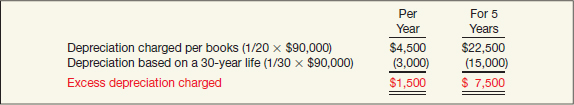

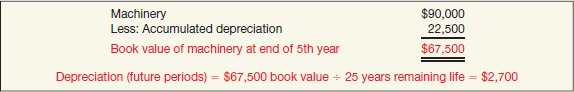

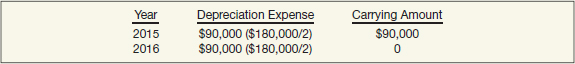

For example, assume that International Paper Co. purchased machinery with an original cost of $90,000. It estimates a 20-year life with no salvage value. However, during year 6, International Paper estimates that it will use the machine for an additional 25 years. Its total life, therefore, will be 30 years instead of 20. Depreciation has been recorded at the rate of 1/20 of $90,000, or $4,500 per year by the straight-line method. On the basis of a 30-year life, International Paper should have recorded depreciation as 1/30 of $90,000, or $3,000 per year. It has therefore overstated depreciation, and understated net income, by $1,500 for each of the past five years, or a total amount of $7,500. Illustration 11-13 shows this computation.

International Paper should report this change in estimate in the current and prospective periods (prospectively): It should not make any changes in previously reported results. And it does not adjust opening balances nor attempt to “catch up” for prior periods. The reason? Changes in estimates are a continual and inherent part of any estimation process. Continual restatement of prior periods would occur for revisions of estimates unless handled prospectively. Therefore, no entry is made at the time the change in estimate occurs. Charges for depreciation in subsequent periods (assuming use of the straight-line method) are determined by dividing the remaining book value less any salvage value by the remaining estimated life.

The entry to record depreciation for each of the remaining 25 years is:

![]()

What do the numbers mean? DEPRECIATION CHOICES

The amount of depreciation expense recorded depends on both the depreciation method used and estimates of service lives and salvage values of the assets. Differences in these choices and estimates can significantly impact a company's reported results and can make it difficult to compare the depreciation numbers of different companies.

For example, when Willamette Industries extended the estimated service lives of its machinery and equipment by five years, it increased income by nearly $54 million (see Note 4 to the right).

An analyst determines the impact of these management choices and judgments on the amount of depreciation expense by examining the notes to financial statements. For example, Willamette Industries provided the following note to its financial statements.

Note 4: Property, Plant, and Equipment (partial)

During the year, the estimated service lives for most machinery and equipment were extended five years. The change was based upon a study performed by the company's engineering department, comparisons to typical industry practices, and the effect of the company's extensive capital investments which have resulted in a mix of assets with longer productive lives due to technological advances. As a result of the change, net income was increased by $54,000,000.

IMPAIRMENTS

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain the accounting issues related to asset impairment.

The general accounting standard of lower-of-cost-or-market for inventories does not apply to property, plant, and equipment. Even when property, plant, and equipment has suffered partial obsolescence, accountants have been reluctant to reduce the asset's carrying amount. Why? Because, unlike inventories, it is difficult to arrive at a fair value for property, plant, and equipment that is not subjective and arbitrary.

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

The going concern concept assumes that the company can recover the investment in its assets. Under GAAP, companies do not report the fair value of long-lived assets because a going concern does not plan to sell such assets. However, if the assumption of being able to recover the cost of the investment is not valid, then a company should report a reduction in value.

For example, Falconbridge Ltd. Nickel Mines had to decide whether to write off all or a part of its property, plant, and equipment in a nickel-mining operation in the Dominican Republic. The project had been incurring losses because nickel prices were low and operating costs were high. Only if nickel prices increased by approximately 33 percent would the project be reasonably profitable. Whether a write-off was appropriate depended on the future price of nickel. Even if the company decided to write off the asset, how much should be written off?

Recognizing Impairments

As discussed in the opening story, the credit crisis starting in late 2008 has affected many financial and nonfinancial institutions. As a result of the global slump, many companies are considering write-offs of some of their long-lived assets. These write-offs are referred to as impairments.

Various events and changes in circumstances might lead to an impairment. Examples are:

- A significant decrease in the fair value of an asset.

- A significant change in the extent or manner in which an asset is used.

- A significant adverse change in legal factors or in the business climate that affects the value of an asset.

- An accumulation of costs significantly in excess of the amount originally expected to acquire or construct an asset.

- A projection or forecast that demonstrates continuing losses associated with an asset.

![]() See the FASB Codification section (page 618).

See the FASB Codification section (page 618).

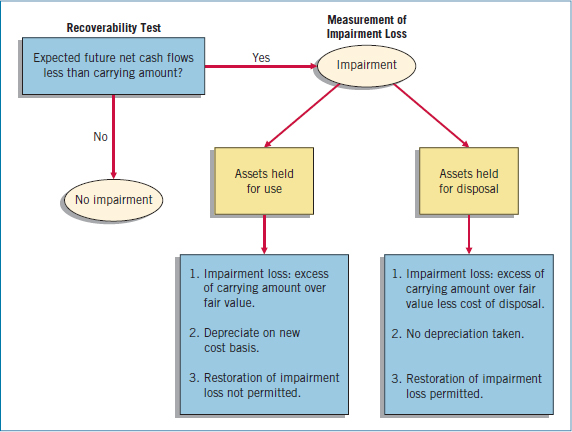

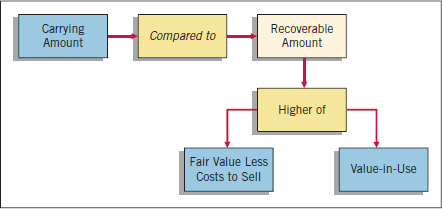

These events or changes in circumstances indicate that the company may not be able to recover the carrying amount of the asset. In that case, a recoverability test is used to determine whether an impairment has occurred.[1]

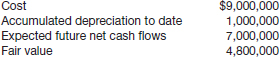

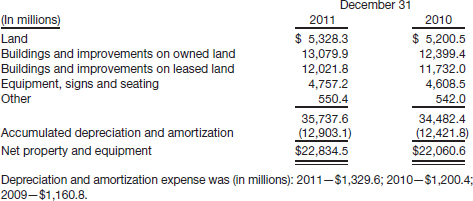

To apply the first step of the recoverability test, a company like UPS estimates the future net cash flows expected from the use of that asset and its eventual disposition. If the sum of the expected future net cash flows (undiscounted) is less than the carrying amount of the asset, UPS considers the asset impaired. Conversely, if the sum of the expected future net cash flows (undiscounted) is equal to or greater than the carrying amount of the asset, no impairment has occurred.

The recoverability test therefore screens for asset impairment. For example, if the expected future net cash flows from an asset are $400,000 and its carrying amount is $350,000, no impairment has occurred. However, if the expected future net cash flows are $300,000, an impairment has occurred. The rationale for the recoverability test relies on a basic presumption: A balance sheet should report long-lived assets at no more than the carrying amounts that are recoverable.

Measuring Impairments

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS also uses a fair value test to measure the impairment loss. However, IFRS does not use the first-stage recoverability test used under GAAP—comparing the undiscounted cash flows to the carrying amount. As a result, the IFRS test is more strict than GAAP.

If the recoverability test indicates an impairment, UPS computes a loss. The impairment loss is the amount by which the carrying amount of the asset exceeds its fair value. How does UPS determine the fair value of an asset? It is measured based on the market price if an active market for the asset exists. If no active market exists, UPS uses the present value of expected future net cash flows to determine fair value.

To summarize, the process of determining an impairment loss is as follows.

- Review events or changes in circumstances for possible impairment.

- If the review indicates a possible impairment, apply the recoverability test. If the sum of the expected future net cash flows from the long-lived asset is less than the carrying amount of the asset, an impairment has occurred.

- Assuming an impairment, the impairment loss is the amount by which the carrying amount of the asset exceeds the fair value of the asset. The fair value is the market price of the asset or the present value of expected future net cash flows.

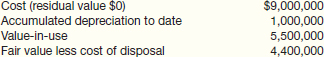

Impairment—Example 1

M. Alou Inc. has equipment that, due to changes in its use, it reviews for possible impairment. The equipment's carrying amount is $600,000 ($800,000 cost less $200,000 accumulated depreciation). Alou determines the expected future net cash flows (undiscounted) from the use of the equipment and its eventual disposal to be $650,000.

The recoverability test indicates that the $650,000 of expected future net cash flows from the equipment's use exceed the carrying amount of $600,000. As a result, no impairment occurred. (Recall that the undiscounted future net cash flows must be less than the carrying amount for Alou to deem an asset to be impaired and to measure the impairment loss.) Therefore, M. Alou Inc. does not recognize an impairment loss in this case.

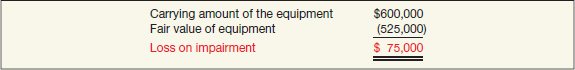

Impairment—Example 2

Assume the same facts as in Example 1, except that the expected future net cash flows from Alou's equipment are $580,000 (instead of $650,000). The recoverability test indicates that the expected future net cash flows of $580,000 from the use of the asset are less than its carrying amount of $600,000. Therefore, an impairment has occurred.

The difference between the carrying amount of Alou's asset and its fair value is the impairment loss. Assuming this asset has a fair value of $525,000, Illustration 11-15 shows the loss computation.

M. Alou records the impairment loss as follows.

![]()

M. Alou Inc. reports the impairment loss as part of income from continuing operations, in the “Other expenses and losses” section. Generally, Alou should not report this loss as an extraordinary item. Costs associated with an impairment loss are the same costs that would flow through operations and that it would report as part of continuing operations. Alou will continue to use these assets in operations. Therefore, it should not report the loss below “Income from continuing operations.”

A company that recognizes an impairment loss should disclose the asset(s) impaired, the events leading to the impairment, the amount of the loss, and how it determined fair value (disclosing the interest rate used, if appropriate).

Restoration of Impairment Loss

After recording an impairment loss, the reduced carrying amount of an asset held for use becomes its new cost basis. A company does not change the new cost basis except for depreciation or amortization in future periods or for additional impairments.

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS permits write-ups for subsequent recoveries of impairment, back up to the original amount before the impairment. GAAP prohibits those write-ups, except for assets to be disposed of.

To illustrate, assume that Damon Company at December 31, 2013, has equipment with a carrying amount of $500,000. Damon determines this asset is impaired and writes it down to its fair value of $400,000. At the end of 2014, Damon determines that the fair value of the asset is $480,000. The carrying amount of the equipment should not change in 2014 except for the depreciation taken in 2014. Damon may not restore an impairment loss for an asset held for use. The rationale for not writing the asset up in value is that the new cost basis puts the impaired asset on an equal basis with other assets that are unimpaired.

Impairment of Assets to Be Disposed Of

What happens if a company intends to dispose of the impaired asset, instead of holding it for use? At one time, Kroger recorded an impairment loss of $54 million on property, plant, and equipment it no longer needed due to store closures. In this case, Kroger reports the impaired asset at the lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value (fair value less costs to sell). Because Kroger intends to dispose of the assets in a short period of time, it uses net realizable value in order to provide a better measure of the net cash flows that it will receive from these assets.

Kroger does not depreciate or amortize assets held for disposal during the period it holds them. The rationale is that depreciation is inconsistent with the notion of assets to be disposed of and with the use of the lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value. In other words, assets held for disposal are like inventory; companies should report them at the lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value.

Because Kroger will recover assets held for disposal through sale rather than through operations, it continually revalues them. Each period, the assets are reported at the lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value. Thus, Kroger can write up or down an asset held for disposal in future periods, as long as the carrying value after the write-up never exceeds the carrying amount of the asset before the impairment. Companies should report losses or gains related to these impaired assets as part of income from continuing operations.

Illustration 11-16 summarizes the key concepts in accounting for impairments.

DEPLETION

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain the accounting procedures for depletion of natural resources.

Natural resources, often called wasting assets, include petroleum, minerals, and timber. They have two main features: (1) the complete removal (consumption) of the asset, and (2) replacement of the asset only by an act of nature. Unlike plant and equipment, natural resources are consumed physically over the period of use and do not maintain their physical characteristics. Still, the accounting problems associated with natural resources are similar to those encountered with fixed assets. The questions to be answered are:

- How do companies establish the cost basis for write-off?

- What pattern of allocation should companies employ?

Recall that the accounting profession uses the term depletion for the process of allocating the cost of natural resources.

Establishing a Depletion Base

How do we determine the depletion base for natural resources? For example, a company like ExxonMobil makes sizable expenditures to find natural resources. And for every successful discovery, there are many failures. Furthermore, the company encounters long delays between the time it incurs costs and the time it obtains the benefits from the extracted resources. As a result, a company in the extractive industries, like ExxonMobil, frequently adopts a conservative policy in accounting for the expenditures related to finding and extracting natural resources.

Computation of the depletion base involves four factors: (1) acquisition cost of the deposit, (2) exploration costs, (3) development costs, and (4) restoration costs.

Acquisition Costs

Acquisition cost is the price ExxonMobil pays to obtain the property right to search and find an undiscovered natural resource. It also can be the price paid for an already-discovered resource. A third type of acquisition cost can be lease payments for property containing a productive natural resource. Included in these acquisition costs are royalty payments to the owner of the property.

Generally, the acquisition cost of natural resources is recorded in an account titled Undeveloped Property. ExxonMobil later assigns that cost to the natural resource if exploration efforts are successful. If the efforts are unsuccessful, it writes off the acquisition cost as a loss.

Exploration Costs

As soon as a company has the right to use the property, it often incurs exploration costs needed to find the resource. When exploration costs are substantial, some companies capitalize them into the depletion base. In the oil and gas industry, where the costs of finding the resource are significant and the risks of finding the resource are very uncertain, most large companies expense these costs. Smaller oil and gas companies often capitalize these exploration costs. We examine the unique issues related to the oil and gas industry on pages 608–609 (see “Continuing Controversy”).

Development Costs

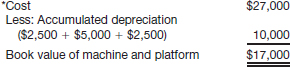

Companies divide development costs into two parts: (1) tangible equipment costs and (2) intangible development costs. Tangible equipment costs include all of the transportation and other heavy equipment needed to extract the resource and get it ready for market. Because companies can move the heavy equipment from one extracting site to another, companies do not normally include tangible equipment costs in the depletion base. Instead, they use separate depreciation charges to allocate the costs of such equipment. However, some tangible assets (e.g., a drilling rig foundation) cannot be moved. Companies depreciate these assets over their useful life or the life of the resource, whichever is shorter.

Intangible development costs, on the other hand, are such items as drilling costs, tunnels, shafts, and wells. These costs have no tangible characteristics but are needed for the production of the natural resource. Intangible development costs are considered part of the depletion base.

Restoration Costs

Companies sometimes incur substantial costs to restore property to its natural state after extraction has occurred. These are restoration costs. Companies consider restoration costs part of the depletion base. The amount included in the depletion base is the fair value of the obligation to restore the property after extraction. A more complete discussion of the accounting for restoration costs and related liabilities (sometimes referred to as asset retirement obligations) is provided in Chapter 13. Similar to other long-lived assets, companies deduct from the depletion base any salvage value to be received on the property.

Write-Off of Resource Cost

Once the company establishes the depletion base, the next problem is determining how to allocate the cost of the natural resource to accounting periods.

Normally, companies compute depletion (often referred to as cost depletion) on a units-of-production method (an activity approach). Thus, depletion is a function of the number of units extracted during the period. In this approach, the total cost of the natural resource less salvage value is divided by the number of units estimated to be in the resource deposit, to obtain a cost per unit of product. To compute depletion, the cost per unit is then multiplied by the number of units extracted.

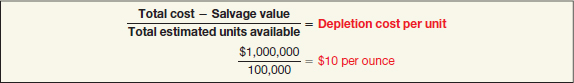

For example, MaClede Co. acquired the right to use 1,000 acres of land in Alaska to mine for gold. The lease cost is $50,000, and the related exploration costs on the property are $100,000. Intangible development costs incurred in opening the mine are $850,000. Total costs related to the mine before the first ounce of gold is extracted are, therefore, $1,000,000. MaClede estimates that the mine will provide approximately 100,000 ounces of gold. Illustration 11-17 shows computation of the depletion cost per unit (depletion rate).

If MaClede extracts 25,000 ounces in the first year, then the depletion for the year is $250,000 (25,000 ounces × $10). It records the depletion as follows.

![]()

MaClede debits Inventory for the total depletion for the year and credits Gold Mine to reduce the carrying value of the natural resource. MaClede credits Inventory when it sells the inventory and debits Cost of Goods Sold. The amount not sold remains in inventory and is reported in the current assets section of the balance sheet.9

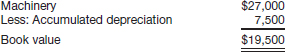

Sometimes companies use an Accumulated Depletion account. In that case, MaClede's balance sheet would present the cost of the natural resource and the amount of accumulated depletion entered to date as follows.

For purposes of homework, credit depletion to the asset account.

MaClede may also depreciate on a units-of-production basis the tangible equipment used in extracting the gold. This approach is appropriate if it can directly assign the estimated lives of the equipment to one given resource deposit. If MaClede uses the equipment on more than one job, other cost allocation methods such as straight-line or accelerated depreciation methods would be more appropriate.

Estimating Recoverable Reserves

Sometimes companies need to change the estimate of recoverable reserves. They do so either because they have new information or because more sophisticated production processes are available. Natural resources such as oil and gas deposits and some rare metals have recently provided the greatest challenges. Estimates of these reserves are in large measure merely “knowledgeable guesses.”

This problem is the same as accounting for changes in estimates for the useful lives of plant and equipment. The procedure is to revise the depletion rate on a prospective basis: A company divides the remaining cost by the new estimate of the recoverable reserves. This approach has much merit because the required estimates are so uncertain.

What do the numbers mean? RESERVE SURPRISE

Cuts in the estimates of oil and natural gas reserves at Royal Dutch Shell, El Paso Corporation, and other energy companies at one time highlighted the importance of reserve disclosures. Investors appeared to believe that these disclosures provide useful information for assessing the future cash flows from a company's oil and gas reserves. For example, when Shell's estimates turned out to be overly optimistic (to the tune of 3.9 billion barrels or 20 percent of reserves), Shell's stock price fell.

The experience at Shell and other companies has led the SEC to look at how companies are estimating their “proved” reserves. Proved reserves are quantities of oil and gas that can be shown “with reasonable certainty to be recoverable in future years….” The phrase “reasonable certainty” is crucial to this guidance, but differences in interpretation of what is reasonably certain can result in a wide range of estimates.

In one case, for example, ExxonMobil's estimate was 29 percent higher than an estimate the SEC developed. ExxonMobil was more optimistic about the effects of new technology that enables the industry to retrieve more of the oil and gas it finds. Thus, to ensure the continued usefulness of reserve information disclosures, the SEC continues to work on a measurement methodology that keeps up with technology changes in the oil and gas industry.

Sources: S. Labaton and J. Gerth, “At Shell, New Accounting and Rosier Outlook,” New York Times (nytimes.com) (March 12, 2004); and J. Ball, C. Cummins, and B. Bahree, “Big Oil Differs with SEC on Methods to Calculate the Industry's Reserves,” Wall Street Journal (February 24, 2005), p. C1.

Liquidating Dividends

A company often owns as its only major asset a property from which it intends to extract natural resources. If the company does not expect to purchase additional properties, it may gradually distribute to stockholders their capital investments by paying liquidating dividends, which are dividends greater than the amount of accumulated net income.

The major accounting problem is to distinguish between dividends that are a return of capital and those that are not. Because the dividend is a return of the investor's original contribution, the company issuing a liquidating dividend should debit Paid-in Capital in Excess of Par for that portion related to the original investment, instead of debiting Retained Earnings.

To illustrate, at year-end, Callahan Mining had a retained earnings balance of $1,650,000, accumulated depletion on mineral properties of $2,100,000, and paid-in capital in excess of par of $5,435,493. Callahan's board declared a dividend of $3 per share on the 1,000,000 shares outstanding. It records the $3,000,000 cash dividend as follows.

![]()

Callahan must inform stockholders that the $3 dividend per share represents a $1.65 ($1,650,000 ÷ 1,000,000 shares) per share return on investment and a $1.35 ($1,350,000 ÷ 1,000,000 shares) per share liquidating dividend.

Continuing Controversy

A major controversy relates to the accounting for exploration costs in the oil and gas industry. Conceptually, the question is whether unsuccessful ventures are a cost of those that are successful. Those who hold the full-cost concept argue that the cost of drilling a dry hole is a cost needed to find the commercially profitable wells. Others believe that companies should capitalize only the costs of successful projects. This is the successful-efforts concept. Its proponents believe that the only relevant measure for a project is the cost directly related to that project, and that companies should report any remaining costs as period charges. In addition, they argue that an unsuccessful company will end up capitalizing many costs that will make it, over a short period of time, show no less income than does one that is successful.10

The FASB has attempted to narrow the available alternatives, with little success. Here is a brief history of the debate.

- 1977—The FASB required oil and gas companies to follow successful-efforts accounting. Small oil and gas producers, voicing strong opposition, lobbied extensively in Congress. Governmental agencies assessed the implications of this standard from a public interest perspective and reacted contrary to the FASB's position.11

- 1978—In response to criticisms of the FASB's actions, the SEC reexamined the issue and found both the successful-efforts and full-cost approaches inadequate. Neither method, said the SEC, reflects the economic substance of oil and gas exploration. As a substitute, the SEC argued in favor of a yet-to-be developed method, reserve recognition accounting (RRA), which it believed would provide more useful information. Under RRA, as soon as a company discovers oil, it reports the value of the oil on the balance sheet and in the income statement. Thus, RRA is a fair value approach, in contrast to full-costing and successful-efforts, which are historical cost approaches. The use of RRA would make a substantial difference in the balance sheets and income statements of oil companies. For example, Atlantic Richfield Co. at one time reported net producing property of $2.6 billion. Under RRA, the same properties would be valued at $11.8 billion.

- 1979–1981—As a result of the SEC's actions, the FASB issued another standard that suspended the requirement that companies follow successful-efforts accounting. Therefore, full-costing was again permissible. In attempting to implement RRA, however, the SEC encountered practical problems in estimating (1) the amount of the reserves, (2) the future production costs, (3) the periods of expected disposal, (4) the discount rate, and (5) the selling price. Companies needed an estimate for each of these to arrive at an accurate valuation of existing reserves. Estimating the future selling price, appropriate discount rate, and future extraction and delivery costs of reserves that are years away from realization can be a formidable task.

- 1981—The SEC abandoned RRA in the primary financial statements of oil and gas producers. The SEC decided that RRA did not possess the required degree of reliability for use as a primary method of financial reporting. However, it continued to stress the need for some form of fair-value-based disclosure for oil and gas reserves. As a result, the profession now requires fair value disclosures for those natural resources.

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS also permits companies to use either full-cost or successful-efforts approaches.

Currently, companies can use either the full-cost approach or the successful-efforts approach. It does seem ironic that Congress directed the FASB to develop one method of accounting for the oil and gas industry, and when the FASB did so, the government chose not to accept it. Subsequently, the SEC attempted to develop a new approach, failed, and then urged the FASB to develop the disclosure requirements in this area. After all these changes, the two alternatives still exist.12

Evolving Issue FULL-COST OR SUCCESSFUL-EFFORTS?

Evolving Issue FULL-COST OR SUCCESSFUL-EFFORTS?

The controversy in the oil and gas industry provides a number of lessons. First, it demonstrates the strong influence that the federal government has in financial reporting matters. Second, the concern for economic consequences places pressure on the FASB to weigh the economic effects of any required standard. Third, the experience with RRA highlights the problems that accompany any proposed change from an historical cost to a fair value approach. Fourth, this controversy illustrates the difficulty of establishing standards when affected groups have differing viewpoints.

Indeed, failure to consider the economic consequences of accounting principles is a frequent criticism of the profession. However, the neutrality concept requires that the statements be free from bias. Freedom from bias requires that the statements reflect economic reality, even if undesirable effects occur. Finally, the debate over oil and gas accounting reinforces the need for a conceptual framework with carefully developed guidelines for recognition, measurement, and reporting, so that interested parties can more easily resolve issues of this nature in the future.

PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS

Presentation of Property, Plant, Equipment, and Natural Resources

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain how to report and analyze property, plant, equipment, and natural resources.

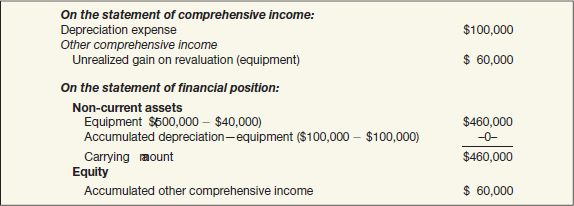

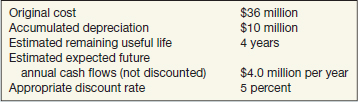

A company should disclose the basis of valuation—usually historical cost—for property, plant, equipment, and natural resources along with pledges, liens, and other commitments related to these assets. It should not offset any liability secured by property, plant, equipment, and natural resources against these assets. Instead, this obligation should be reported in the liabilities section. The company should segregate property, plant, and equipment not currently employed as producing assets in the business (such as idle facilities or land held as an investment) from assets used in operations.

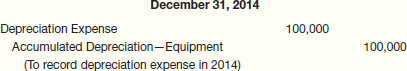

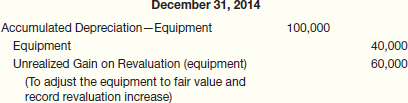

When depreciating assets, a company credits a valuation account such as Accumulated Depreciation—Equipment. Using an accumulated depreciation account permits the user of the financial statements to see the original cost of the asset and the amount of depreciation that the company charged to expense in past years.

When depleting natural resources, some companies use an accumulated depletion account. Many, however, simply credit the natural resource account directly. The rationale for this approach is that the natural resources are physically consumed, making direct reduction of the cost of the natural resources appropriate.

Because of the significant impact on the financial statements of the depreciation method(s) used, companies should disclose the following.

- Depreciation expense for the period.

- Balances of major classes of depreciable assets, by nature and function.

- Accumulated depreciation, either by major classes of depreciable assets or in total.

- A general description of the method or methods used in computing depreciation with respect to major classes of depreciable assets.[2]13

Special disclosure requirements relate to the oil and gas industry. Companies engaged in these activities must disclose the following in their financial statements: (1) the basic method of accounting for those costs incurred in oil and gas producing activities (e.g., full-cost versus successful-efforts), and (2) how the company disposes of costs relating to extractive activities (e.g., dispensing immediately versus depreciation and depletion). [3]14

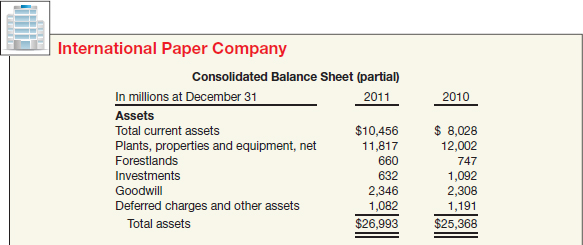

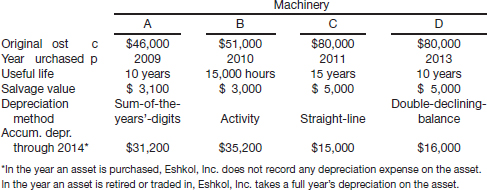

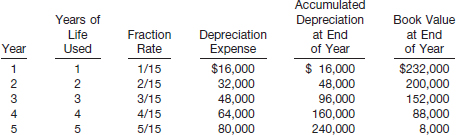

The 2011 annual report of International Paper Company in Illustration 11-19 shows an acceptable disclosure. It uses condensed balance sheet data supplemented with details and policies in notes to the financial statements.

Analysis of Property, Plant, and Equipment

Analysts evaluate assets relative to activity (turnover) and profitability.

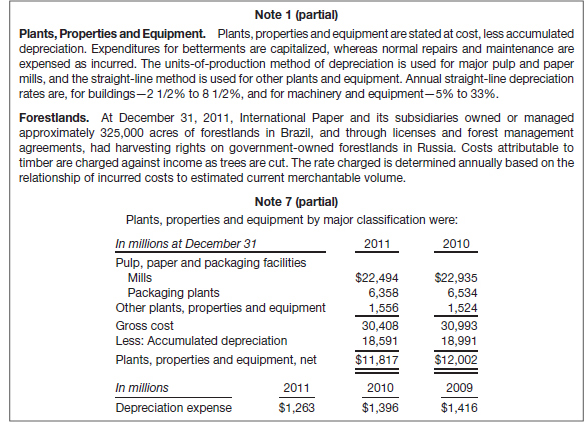

Asset Turnover

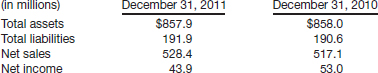

How efficiently a company uses its assets to generate sales is measured by the asset turnover. This ratio divides net sales by average total assets for the period. The resulting number is the dollars of sales produced by each dollar invested in assets. To illustrate, we use the following data from the Johnson & Johnson 2011 annual report. Illustration 11-20 shows computation of the asset turnover.

The asset turnover shows that Johnson & Johnson generated sales of $0.60 per dollar of assets in the year ended January 2, 2012.

Asset turnovers vary considerably among industries. For example, a large utility like Ameren has a ratio of 0.32 times. A large grocery chain like Kroger has a ratio of 2.73 times. Thus, in comparing performance among companies based on the asset turnover ratio, you need to consider the ratio within the context of the industry in which a company operates.

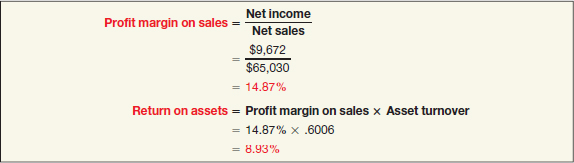

Profit Margin on Sales

Another measure for analyzing the use of property, plant, and equipment is the profit margin on sales (return on sales). Calculated as net income divided by net sales, this profitability ratio does not, by itself, answer the question of how profitably a company uses its assets. But by relating the profit margin on sales to the asset turnover during a period of time, we can ascertain how profitably the company used assets during that period of time in a measure of the return on assets. Using the Johnson & Johnson data shown on page 611, we compute the profit margin on sales and the return on assets as follows.

Return on Assets

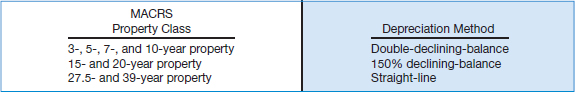

The return on assets (ROA) is computed directly by dividing net income by average total assets. Using Johnson & Johnson's data, we compute the ratio as follows.

![]() You will want to read the IFRS INSIGHTS on pages 637–646 for discussion of IFRS related to property, plant, and equipment.

You will want to read the IFRS INSIGHTS on pages 637–646 for discussion of IFRS related to property, plant, and equipment.

The 8.93 percent return on assets computed in this manner equals the 8.93 percent rate computed by multiplying the profit margin on sales by the asset turnover. The rate of return on assets measures profitability well because it combines the effects of profit margin and asset turnover.

KEY TERMS

accelerated depreciation methods, 594

activity method, 593

amortization, 590

asset turnover, 611

composite approach, 596

composite depreciation rate, 596

cost depletion, 606

declining-balance method, 595

decreasing-charge methods, 594

depletion, 590, 604

depreciation, 590

depreciation base, 590

development costs, 605

double-declining-balance method, 595

exploration costs, 605

full-cost concept, 608

group method, 595

impairment, 601

inadequacy, 591

liquidating dividends, 607

natural resources, 604

obsolescence, 591

percentage depletion, 606(n)

profit margin on sales, 612

recoverability test, 602

reserve recognition accounting (RRA), 608

restoration costs, 605

return on assets (ROA), 612

salvage value, 590

straight-line method, 593

successful-efforts concept, 608

sum-of-the-years'-digits method, 594

supersession, 591

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES

![]() Explain the concept of depreciation. Depreciation allocates the cost of tangible assets to expense in a systematic and rational manner to those periods expected to benefit from the use of the asset.

Explain the concept of depreciation. Depreciation allocates the cost of tangible assets to expense in a systematic and rational manner to those periods expected to benefit from the use of the asset.

![]() Identify the factors involved in the depreciation process. Three factors involved in the depreciation process are (1) determining the depreciation base for the asset, (2) estimating service lives, and (3) selecting a method of cost apportionment (depreciation).

Identify the factors involved in the depreciation process. Three factors involved in the depreciation process are (1) determining the depreciation base for the asset, (2) estimating service lives, and (3) selecting a method of cost apportionment (depreciation).

![]() Compare activity, straight-line, and decreasing-charge methods of depreciation. (1) Activity method: Assumes that depreciation is a function of use or productivity instead of the passage of time. The life of the asset is considered in terms of either the output it provides, or an input measure such as the number of hours it works. (2) Straight-line method: Considers depreciation a function of time instead of a function of usage. The straight-line procedure is often the most conceptually appropriate when the decline in usefulness is constant from period to period. (3) Decreasing-charge methods: Provide for a higher depreciation cost in the earlier years and lower charges in later periods. The main justification for this approach is that the asset is the most productive in its early years.

Compare activity, straight-line, and decreasing-charge methods of depreciation. (1) Activity method: Assumes that depreciation is a function of use or productivity instead of the passage of time. The life of the asset is considered in terms of either the output it provides, or an input measure such as the number of hours it works. (2) Straight-line method: Considers depreciation a function of time instead of a function of usage. The straight-line procedure is often the most conceptually appropriate when the decline in usefulness is constant from period to period. (3) Decreasing-charge methods: Provide for a higher depreciation cost in the earlier years and lower charges in later periods. The main justification for this approach is that the asset is the most productive in its early years.

![]() Explain special depreciation methods. Two special depreciation methods are as follows. (1) Group and composite methods: The group method is frequently used when the assets are fairly similar in nature and have approximately the same useful lives. The composite method may be used when the assets are dissimilar and have different lives. (2) Hybrid or combination methods: These methods may combine straight-line/activity approaches.

Explain special depreciation methods. Two special depreciation methods are as follows. (1) Group and composite methods: The group method is frequently used when the assets are fairly similar in nature and have approximately the same useful lives. The composite method may be used when the assets are dissimilar and have different lives. (2) Hybrid or combination methods: These methods may combine straight-line/activity approaches.

![]() Explain the accounting issues related to asset impairment. The process to determine an impairment loss is as follows. (1) Review events and changes in circumstances for possible impairment. (2) If events or changes suggest impairment, determine if the sum of the expected future net cash flows from the long-lived asset is less than the carrying amount of the asset. If less, measure the impairment loss. (3) The impairment loss is the amount by which the carrying amount of the asset exceeds the fair value of the asset.

Explain the accounting issues related to asset impairment. The process to determine an impairment loss is as follows. (1) Review events and changes in circumstances for possible impairment. (2) If events or changes suggest impairment, determine if the sum of the expected future net cash flows from the long-lived asset is less than the carrying amount of the asset. If less, measure the impairment loss. (3) The impairment loss is the amount by which the carrying amount of the asset exceeds the fair value of the asset.

After a company records an impairment loss, the reduced carrying amount of the long-lived asset is its new cost basis. Impairment losses may not be restored for assets held for use. If the company expects to dispose of the asset, it should report the impaired asset at the lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value. It is not depreciated. It can be continuously revalued, as long as the write-up is never to an amount greater than the carrying amount before impairment.

![]() Explain the accounting procedures for depletion of natural resources. To account for depletion of natural resources, companies (1) establish the depletion base and (2) write off resource cost. Four factors are part of establishing the depletion base: (a) acquisition costs, (b) exploration costs, (c) development costs, and (d) restoration costs. To write off resource cost, companies normally compute depletion on the units-of-production method. Thus, depletion is a function of the number of units withdrawn during the period. To obtain a cost per unit of product, the total cost of the natural resource less salvage value is divided by the number of units estimated to be in the resource deposit, to obtain a cost per unit of product. To compute depletion, this cost per unit is multiplied by the number of units withdrawn.

Explain the accounting procedures for depletion of natural resources. To account for depletion of natural resources, companies (1) establish the depletion base and (2) write off resource cost. Four factors are part of establishing the depletion base: (a) acquisition costs, (b) exploration costs, (c) development costs, and (d) restoration costs. To write off resource cost, companies normally compute depletion on the units-of-production method. Thus, depletion is a function of the number of units withdrawn during the period. To obtain a cost per unit of product, the total cost of the natural resource less salvage value is divided by the number of units estimated to be in the resource deposit, to obtain a cost per unit of product. To compute depletion, this cost per unit is multiplied by the number of units withdrawn.

![]() Explain how to report and analyze property, plant, equipment, and natural resources. The basis of valuation for property, plant, and equipment and for natural resources should be disclosed along with pledges, liens, and other commitments related to these assets. Companies should not offset any liability secured by property, plant, and equipment or by natural resources against these assets, but should report it in the liabilities section. When depreciating assets, credit a valuation account normally called Accumulated Depreciation. When depleting assets, use an accumulated depletion account, or credit the depletion directly to the natural resource account. Companies engaged in significant oil and gas producing activities must provide additional disclosures about these activities. Analysis may be performed to evaluate the asset turnover, profit margin on sales, and return on assets.

Explain how to report and analyze property, plant, equipment, and natural resources. The basis of valuation for property, plant, and equipment and for natural resources should be disclosed along with pledges, liens, and other commitments related to these assets. Companies should not offset any liability secured by property, plant, and equipment or by natural resources against these assets, but should report it in the liabilities section. When depreciating assets, credit a valuation account normally called Accumulated Depreciation. When depleting assets, use an accumulated depletion account, or credit the depletion directly to the natural resource account. Companies engaged in significant oil and gas producing activities must provide additional disclosures about these activities. Analysis may be performed to evaluate the asset turnover, profit margin on sales, and return on assets.

APPENDIX 11A INCOME TAX DEPRECIATION

For the most part, a financial accounting course does not address issues related to the computation of income taxes. However, because the concepts of tax depreciation are similar to those of book depreciation and because tax depreciation methods are sometimes adopted for book purposes, we present an overview of this subject.

Congress passed the Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS) as part of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981. The goal was to stimulate capital investment through faster write-offs and to bring more uniformity to the write-off period. For assets purchased in the years 1981 through 1986, companies use ACRS and its preestablished “cost recovery periods” for various classes of assets.

In the Tax Reform Act of 1986 Congress enacted a Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System, known as MACRS. It applies to depreciable assets placed in service in 1987 and later. The following discussion is based on these MACRS rules. Realize that tax depreciation rules are subject to change annually.15

MODIFIED ACCELERATED COST RECOVERY SYSTEM

The computation of depreciation under MACRS differs from the computation under GAAP in three respects: (1) a mandated tax life, which is generally shorter than the economic life; (2) cost recovery on an accelerated basis; and (3) an assigned salvage value of zero.

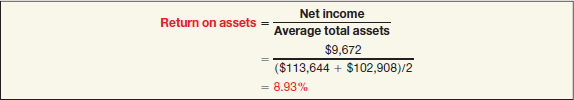

Tax Lives (Recovery Periods)

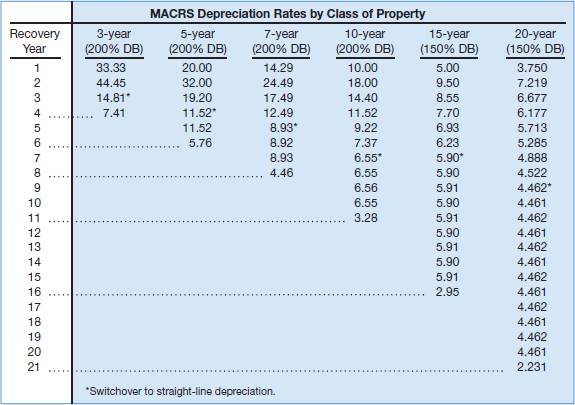

Each item of depreciable property belongs to a property class. The recovery period (depreciable tax life) of an asset depends on its property class. Illustration 11A-1 presents the MACRS property classes.

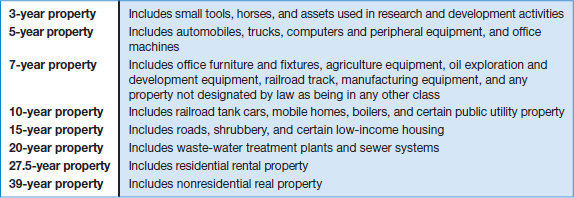

Tax Depreciation Methods

Companies compute depreciation expense using the tax basis—usually the cost—of the asset. The depreciation method depends on the MACRS property class, as shown below.

Depreciation computations for income tax purposes are based on the half-year convention. That is, a half year of depreciation is allowable in the year of acquisition and in the year of disposition.16 A company depreciates an asset to a zero value so that there is no salvage value at the end of its MACRS life.

Use of IRS-published tables, shown in Illustration 11A-3, simplifies application of these depreciation methods.

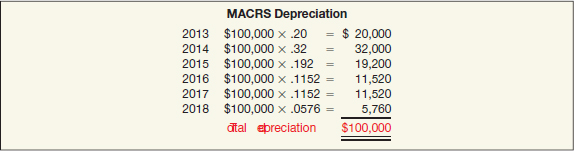

Example of MACRS

To illustrate depreciation computations under both MACRS and GAAP straight-line accounting, assume the following facts for a computer and peripheral equipment purchased by Denise Rode Company on January 1, 2013.

Using the rates from the MACRS depreciation rate schedule for a 5-year class of property, Rode computes depreciation as follows for tax purposes.

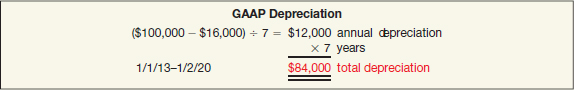

Rode computes the depreciation under GAAP straight-line method, with $16,000 of estimated salvage value and an estimated useful life of 7 years, as shown in Illustration 11A-5.