CHAPTER 14 Long-Term Liabilities

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the formal procedures associated with issuing long-term debt.

- Identify various types of bond issues.

- Describe the accounting valuation for bonds at date of issuance.

- Apply the methods of bond discount and premium amortization.

- Describe the accounting for the extinguishment of debt.

- Explain the accounting for long-term notes payable.

- Describe the accounting for the fair value option.

- Explain the reporting of off-balance-sheet financing arrangements.

- Indicate how to present and analyze long-term debt.

Going Long

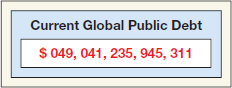

The clock is ticking. Every second, it seems, someone in the world takes on more debt. The idea of a debt clock for an individual nation is familiar to anyone who has been to Times Square in New York, where the American public shortfall is revealed. The global debt clock shown below (accessed in October 2012) indicates the global figure for almost all government debts in dollar terms.

Does it matter? After all, world governments owe the money to their own citizens, not to the Martians. But the rising total is important for two reasons. First, when government debt rises faster than economic output (as it has been doing in recent years), this implies more state interference in the economy and higher taxes in the future. Second, debt must be rolled over at regular intervals. This creates a recurring popularity test for individual governments, much like reality-TV contestants facing a public phone vote every week. Fail that vote, as various euro-zone governments have done, and the country (and its neighbors) can be plunged into crisis.

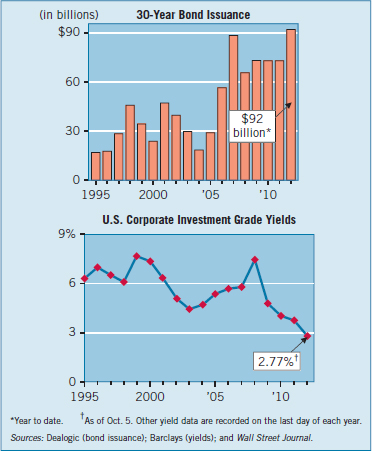

In addition to government debt, companies are issuing corporate debt at a record pace. Why this trend? For one thing, low interest rates and rising inflows into fixed-income funds have triggered record bond issuances as banks cut back lending. In addition, for some high-rated companies, it can be riskier to borrow from a bank than the bond markets. The reason: High-rated companies tend to rely on short-term commercial paper, backed up by undrawn loans, to fund working capital but are left stranded when these markets freeze up. Some are now financing themselves with longer-term bonds instead.

In fact, nonfinancial companies are issuing 30-year bonds at a record pace, as they look to increase long-term borrowings, lock in low interest rates, and take advantage of investor demand. The charts on the next page show the substantial increase in bonds issues as interest rates have fallen.

Companies, like Phillip Morris, Medtronic, Plains All American Pipeline, and Simon Property Group, have all sold 30-year bonds recently. Increases in the issuance of these bonds suggest confidence in the economy as investors appear comfortable holding such long-term investments. In addition, companies have a strong appetite for issuing these bonds because they provide a substantial cash infusion at a relatively low interest rate. Hopefully, it will work out for both the investor and the company in the long run.

![]() CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

- See the Underlying Concepts on page 774.

- Read the Evolving Issue on page 788 for a discussion of recognizing debt using the fair value option.

![]() INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

- See the International Perspectives on pages 770, 775, and 785.

- Read the IFRS Insights on pages 815–819 for a discussion of:

- Effective-interest method

- Extinguishments with modifications of terms

Sources: A. Sakoui and N. Bullock, “Companies Choose Bonds for Cheap Funds,” Financial Times (October 12, 2009); http://www.economist.com/content/global_debt_clock; and V. Monga, “Companies Feast on Cheap Money Market for 30-Year Bonds, Priced at Stark Lows, Brings Out GE, UPS and Other Once-Shy Issuers,” Wall Street Journal (October 8, 2012).

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 14

As our opening story indicates, companies may rely on different forms of long-term borrowing, depending on market conditions and the features of various noncurrent liabilities. In this chapter, we explain the accounting issues related to long-term liabilities. The content and organization of the chapter are as follows.

BONDS PAYABLE

Long-term debt consists of probable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from present obligations that are not payable within a year or the operating cycle of the company, whichever is longer. Bonds payable, long-term notes payable, mortgages payable, pension liabilities, and lease liabilities are examples of long-term liabilities.

A corporation, per its bylaws, usually requires approval by the board of directors and the stockholders before bonds or notes can be issued. The same holds true for other types of long-term debt arrangements.

Generally, long-term debt has various covenants or restrictions that protect both lenders and borrowers. The indenture or agreement often includes the amounts authorized to be issued, interest rate, due date(s), call provisions, property pledged as security, sinking fund requirements, working capital and dividend restrictions, and limitations concerning the assumption of additional debt. Companies should describe these features in the body of the financial statements or the notes if important for a complete understanding of the financial position and the results of operations.

Although it would seem that these covenants provide adequate protection to the long-term debtholder, many bondholders suffer considerable losses when companies add more debt to the capital structure. Consider what can happen to bondholders in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), which are usually led by management. In an LBO of RJR Nabisco, for example, solidly rated 9⅜ percent bonds due in 2016 plunged 20 percent in value when management announced the leveraged buyout. Such a loss in value occurs because the additional debt added to the capital structure increases the likelihood of default. Although covenants protect bondholders, they can still suffer losses when debt levels get too high.

Issuing Bonds

A bond arises from a contract known as a bond indenture. A bond represents a promise to pay (1) a sum of money at a designated maturity date, plus (2) periodic interest at a specified rate on the maturity amount (face value). Individual bonds are evidenced by a paper certificate and typically have a $1,000 face value. Companies usually make bond interest payments semiannually, although the interest rate is generally expressed as an annual rate. The main purpose of bonds is to borrow for the long term when the amount of capital needed is too large for one lender to supply. By issuing bonds in $100, $1,000, or $10,000 denominations, a company can divide a large amount of long-term indebtedness into many small investing units, thus enabling more than one lender to participate in the loan.

A company may sell an entire bond issue to an investment bank, which acts as a selling agent in the process of marketing the bonds. In such arrangements, investment banks may either underwrite the entire issue by guaranteeing a certain sum to the company, thus taking the risk of selling the bonds for whatever price they can get (firm underwriting). Or they may sell the bond issue for a commission on the proceeds of the sale (best-efforts underwriting). Alternatively, the issuing company may sell the bonds directly to a large institution, financial or otherwise, without the aid of an underwriter (private placement).

Types of Bonds

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Identify various types of bond issues.

Presented on the next page, we define some of the more common types of bonds found in practice.

TYPES OF BONDS

SECURED AND UNSECURED BONDS. Secured bonds are backed by a pledge of some sort of collateral. Mortgage bonds are secured by a claim on real estate. Collateral trust bonds are secured by stocks and bonds of other corporations. Bonds not backed by collateral are unsecured. A debenture bond is unsecured. A “junk bond” is unsecured and also very risky, and therefore pays a high interest rate. Companies often use these bonds to finance leveraged buyouts.

TERM, SERIAL BONDS, AND CALLABLE BONDS. Bond issues that mature on a single date are called term bonds. Issues that mature in installments are called serial bonds. Serially maturing bonds are frequently used by school or sanitary districts, municipalities, or other local taxing bodies that receive money through a special levy. Callable bonds give the issuer the right to call and redeem the bonds prior to maturity.

CONVERTIBLE, COMMODITY-BACKED, AND DEEP-DISCOUNT BONDS. If bonds are convertible into other securities of the corporation for a specified time after issuance, they are convertible bonds.

Two types of bonds have been developed in an attempt to attract capital in a tight money market—commodity-backed bonds and deep-discount bonds. Commodity-backed bonds (also called asset-linked bonds) are redeemable in measures of a commodity, such as barrels of oil, tons of coal, or ounces of rare metal. To illustrate, Sunshine Mining, a silver-mining company, sold two issues of bonds redeemable with either $1,000 in cash or 50 ounces of silver, whichever is greater at maturity, and that have a stated interest rate of 8½ percent. The accounting problem is one of projecting the maturity value, especially since silver has fluctuated between $4 and $40 an ounce since issuance.

JCPenney Company sold the first publicly marketed long-term debt securities in the United States that do not bear interest. These deep-discount bonds, also referred to as zero-interest debenture bonds, are sold at a discount that provides the buyer's total interest payoff at maturity.

REGISTERED AND BEARER (COUPON) BONDS. Bonds issued in the name of the owner are registered bonds and require surrender of the certificate and issuance of a new certificate to complete a sale. A bearer or coupon bond, however, is not recorded in the name of the owner and may be transferred from one owner to another by mere delivery.

INCOME AND REVENUE BONDS. Income bonds pay no interest unless the issuing company is profitable. Revenue bonds, so called because the interest on them is paid from specified revenue sources, are most frequently issued by airports, school districts, counties, toll-road authorities, and governmental bodies.

What do the numbers mean? ALL ABOUT BONDS

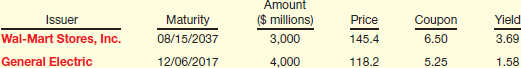

How do investors monitor their bond investments? One way is to review the bond listings found in the newspaper or online. Corporate bond listings show the coupon (interest) rate, maturity date, and last price. However, because corporate bonds are more actively held by large institutional investors, the listings also indicate the current yield and the volume traded. Corporate bond listings would look like those below.

The companies issuing the bonds are listed in the first column, in this case, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. and General Electric. Immediately after the names is a column with the maturity date, followed by the amount and price of the bonds. As indicated, Wal-Mart pays a coupon rate of 6.5 percent and yields 3.69 percent. General Electric pays a coupon rate of 5.25 percent and yields 1.58 percent. The lower yield for General Electric arises because the time to maturity is much shorter than Wal-Mart's.

Also, interest rates and the bond's term to maturity have a real effect on bond prices. For example, an increase in interest rates will lead to a decline in bond values. Similarly, a decrease in interest rates will lead to a rise in bond values. The data reported in the table to the right, based on three different bond funds, demonstrate these relationships between interest rate changes and bond values.

Another factor that affects bond prices is the call feature, which decreases the value of the bond. Investors must be rewarded for the risk that the issuer will call the bond if interest rates decline, which would force the investor to reinvest at lower rates.

VALUATION OF BONDS PAYABLE—DISCOUNT AND PREMIUM

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe the accounting valuation for bonds at date of issuance.

The issuance and marketing of bonds to the public does not happen overnight. It usually takes weeks or even months. First, the issuing company must arrange for underwriters that will help market and sell the bonds. Then, it must obtain the Securities and Exchange Commission's approval of the bond issue, undergo audits, and issue a prospectus (a document which describes the features of the bond and related financial information). Finally, the company must generally have the bond certificates printed. Frequently, the issuing company establishes the terms of a bond indenture well in advance of the sale of the bonds. Between the time the company sets these terms and the time it issues the bonds, the market conditions and the financial position of the issuing corporation may change significantly. Such changes affect the marketability of the bonds and thus their selling price.

The selling price of a bond issue is set by the supply and demand of buyers and sellers, relative risk, market conditions, and the state of the economy. The investment community values a bond at the present value of its expected future cash flows, which consist of (1) interest and (2) principal. The rate used to compute the present value of these cash flows is the interest rate that provides an acceptable return on an investment commensurate with the issuer's risk characteristics.

The interest rate written in the terms of the bond indenture (and often printed on the bond certificate) is known as the stated, coupon, or nominal rate. The issuer of the bonds sets this rate. The stated rate is expressed as a percentage of the face value of the bonds (also called the par value, principal amount, or maturity value).

If the rate employed by the investment community (buyers) differs from the stated rate, the present value of the bonds computed by the buyers (and the current purchase price) will differ from the face value of the bonds. The difference between the face value and the present value of the bonds determines the actual price that buyers pay for the bonds. This difference is either a discount or premium.1

- If the bonds sell for less than face value, they sell at a discount.

- If the bonds sell for more than face value, they sell at a premium.

The rate of interest actually earned by the bondholders is called the effective yield or market rate. If bonds sell at a discount, the effective yield exceeds the stated rate. Conversely, if bonds sell at a premium, the effective yield is lower than the stated rate. Several variables affect the bond's price while it is outstanding, most notably the market rate of interest. There is an inverse relationship between the market interest rate and the price of the bond.

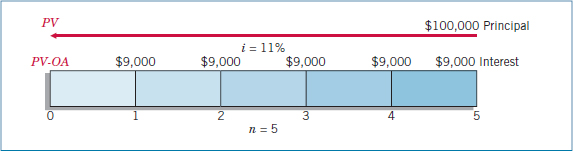

Here we consider an example to illustrate the computation of the present value of a bond issue. Assume that ServiceMaster issues $100,000 in bonds, due in five years with 9 percent interest payable annually at year-end. At the time of issue, the market rate for such bonds is 11 percent. The time diagram in Illustration 14-1 depicts both the interest and the principal cash flows.

The actual principal and interest cash flows are discounted at an 11 percent rate for five periods, as shown in Illustration 14-2.

By paying $92,608.10 at the date of issue, investors earn an effective rate or yield of 11 percent over the five-year term of the bonds. These bonds would sell at a discount of $7,391.90 ($100,000 − $92,608.10). The price at which the bonds sell is typically stated as a percentage of the face or par value of the bonds. For example, the ServiceMaster bonds sold for 92.6 (92.6% of par). If ServiceMaster had received $102,000, then the bonds sold for 102 (102% of par).

When bonds sell at less than face value, it means that investors demand a rate of interest higher than the stated rate. Usually this occurs because the investors can earn a greater rate on alternative investments of equal risk. They cannot change the stated rate, so they refuse to pay face value for the bonds. Thus, by changing the amount invested, they alter the effective rate of return. The investors receive interest at the stated rate computed on the face value, but they actually earn at an effective rate that exceeds the stated rate because they paid less than face value for the bonds. (Later in the chapter, in Illustrations 14-6 and 14-7 (pages 772–773), we show an illustration for a bond that sells at a premium.)

What do the numbers mean? HOW'S MY RATING?

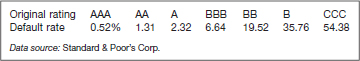

Two major publication companies, Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's Corporation, issue quality ratings on every public debt issue. The following table summarizes the ratings issued by Standard & Poor's, along with historical default rates on bonds with different ratings.

As expected, bonds receiving the highest quality rating of AAA have the lowest historical default rates. Bonds rated below BBB, which are considered below investment grade (“junk bonds”), experience default rates ranging from 20 to 50 percent.

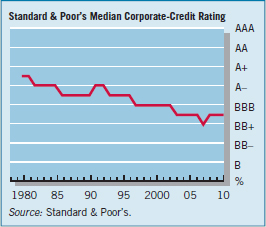

Debt ratings reflect credit quality. The market closely monitors these ratings when determining the required yield and pricing of bonds at issuance and in periods after issuance, especially if a bond's rating is upgraded or downgraded. Unfortunately, the median rating of companies assessed by Standard & Poor's has fallen from A in 1981 to BBB today, as shown in the chart to the right.

The BBB rating is the lowest possible “investment grade” or, to put it another way, is just one notch above “junk” bond status. It should be noted that investors who seek triple-A debt are running out of options. Standard & Poor's recently gave its top rating to just four U.S. industrial companies: Automatic Data Processing, ExxonMobil, Johnson & Johnson, and Microsoft.

Sources: A. Borrus, M. McNamee, and H. Timmons, “The Credit Raters: How They Work and How They Might Work Better,” BusinessWeek (April 8, 2002), pp. 38–40; Standard and Poor's, Global Fixed Income Research, “Fallen Angel Activity” (February 6, 2007); and “Betting the Balance Sheet,” The Economist (June 24, 2010).

Bonds Issued at Par on Interest Date

When a company issues bonds on an interest payment date at par (face value), it accrues no interest. No premium or discount exists. The company simply records the cash proceeds and the face value of the bonds. To illustrate, if Buchanan Company issues at par 10-year term bonds with a par value of $800,000, dated January 1, 2014, and bearing interest at an annual rate of 10 percent payable semiannually on January 1 and July 1, it records the following entry.

![]()

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × .10 × ½) on July 1, 2014, as follows.

![]()

It records accrued interest expense at December 31, 2014 (year-end), as follows.

![]()

Bonds Issued at Discount or Premium on Interest Date

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Apply the methods of bond discount and premium amortization.

If Buchanan Company issues the $800,000 of bonds on January 1, 2014, at 97 (meaning 97% of par), it records the issuance as shown on the top of the next page.

Recall from our earlier discussion that because of its relation to interest, companies amortize the discount and charge it to interest expense over the period of time that the bonds are outstanding.

The straight-line method amortizes a constant amount each interest period (in this case 20 interest periods).2 For example, using the bond discount of $24,000, Buchanan amortizes $1,200 to interest expense each period for 20 periods ($24,000 ÷ 20).

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × 10% × ½) and the bond discount on July 1, 2014, as follows.

![]()

At December 31, 2014, Buchanan makes the following adjusting entry.

![]()

At the end of the first year, 2014, the balance in the Discount on Bonds Payable account is $21,600 ($24,000 − $1,200 − $1,200). Over the term of the bonds, the balance in Discount on Bonds Payable will decrease by the same amount until it has zero balance at the maturity date of the bonds.

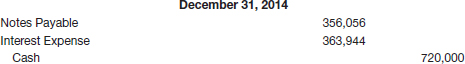

If instead of issuing the bonds on January 1, 2014, Buchanan dates and sells the bonds on October 1, 2014, and if the fiscal year of the corporation ends on December 31, the discount amortized during 2014 would be only 3/12 of 1/10 of $24,000, or $600. Buchanan must also record three months of accrued interest on December 31.

Premium on Bonds Payable is accounted for in a manner similar to that for Discount on Bonds Payable. If Buchanan dates and sells 10-year bonds with a par value of $800,000 on January 1, 2014, at 103, it records the issuance as follows.

![]()

With the bond premium of $24,000, Buchanan amortizes $1,200 to interest expense each period for 20 periods ($24,000 ÷ 20).

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × 10% × ½) and the bond premium on July 1, 2014, as follows.

![]()

At December 31, 2014, Buchanan makes the following adjusting entry.

![]()

Amortization of a discount increases interest expense. Amortization of a premium decreases interest expense. Later in the chapter, we discuss amortization of a discount or premium under the effective-interest method.

The issuer may call some bonds at a stated price after a certain date. This call feature gives the issuing corporation the opportunity to reduce its bonded indebtedness or take advantage of lower interest rates. Whether callable or not, a company must amortize any premium or discount over the bond's life to maturity because early redemption (call of the bond) is not a certainty.

Bonds Issued Between Interest Dates

Companies usually make bond interest payments semiannually, on dates specified in the bond indenture. When companies issue bonds on other than the interest payment dates, buyers of the bonds will pay the seller the interest accrued from the last interest payment date to the date of issue. The purchasers of the bonds, in effect, pay the bond issuer in advance for that portion of the full six-months' interest payment to which they are not entitled because they have not held the bonds for that period. Then, on the next semiannual interest payment date, purchasers will receive the full six-months' interest payment.

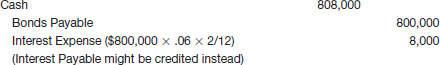

To illustrate, assume that on March 1, 2014, Taft Corporation issues 10-year bonds, dated January 1, 2014, with a par value of $800,000. These bonds have an annual interest rate of 6 percent, payable semiannually on January 1 and July 1. Because Taft issues the bonds between interest dates, it records the bond issuance at par plus accrued interest as follows.

The purchaser advances two months' interest. On July 1, 2014, four months after the date of purchase, Taft pays the purchaser six months' interest. Taft makes the following entry on July 1, 2014.

![]()

The Interest Expense account now contains a debit balance of $16,000, which represents the proper amount of interest expense—four months at 6 percent on $800,000.

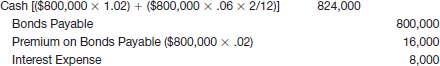

The illustration above was simplified by having the January 1, 2014, bonds issued on March 1, 2014, at par. If, however, Taft issued the 6 percent bonds at 102, its March 1 entry would be:

Taft would amortize the premium from the date of sale (March 1, 2014), not from the date of the bonds (January 1, 2014).

Effective-Interest Method

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS requires the use of the effective-interest method. GAAP permits the use of the straight-line method if not materially different than the effective-interest method.

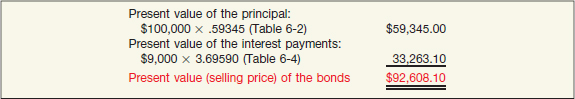

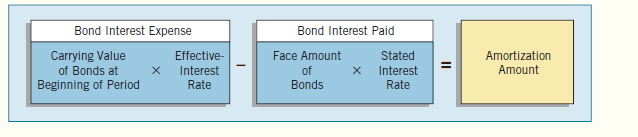

The preferred procedure for amortization of a discount or premium is the effective-interest method (also called present value amortization). Under the effective-interest method, companies:

- Compute bond interest expense first by multiplying the carrying value (book value) of the bonds at the beginning of the period by the effective-interest rate.3

- Determine the bond discount or premium amortization next by comparing the bond interest expense with the interest (cash) to be paid.

Illustration 14-3 depicts graphically the computation of the amortization.

The effective-interest method produces a periodic interest expense equal to a constant percentage of the carrying value of the bonds. Since the percentage is the effective rate of interest incurred by the borrower at the time of issuance, the effective-interest method matches expenses with revenues better than the straight-line method.

![]() See the FASB Codification section (page 798).

See the FASB Codification section (page 798).

Both the effective-interest and straight-line methods result in the same total amount of interest expense over the term of the bonds. However, when the annual amounts are materially different, generally accepted accounting principles require use of the effective-interest method. [1]

Bonds Issued at a Discount

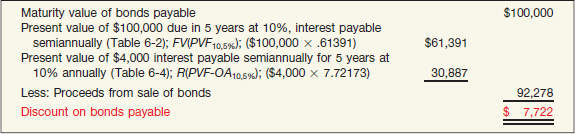

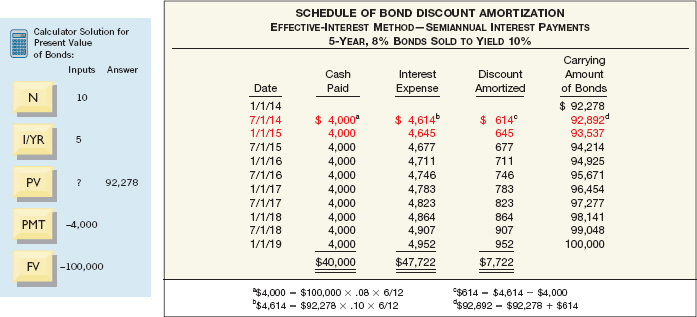

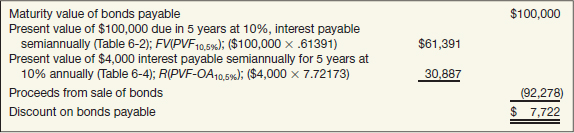

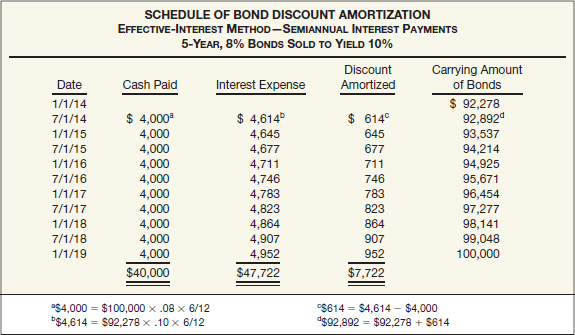

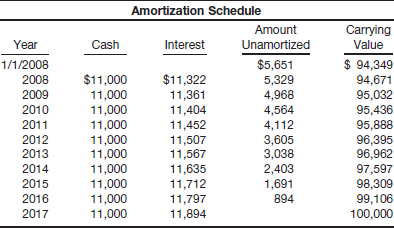

To illustrate amortization of a discount under the effective-interest method, Evermaster Corporation issued $100,000 of 8 percent term bonds on January 1, 2014, due on January 1, 2019, with interest payable each July 1 and January 1. Because the investors required an effective-interest rate of 10 percent, they paid $92,278 for the $100,000 of bonds, creating a $7,722 discount. Evermaster computes the $7,722 discount as follows.4

The five-year amortization schedule appears in Illustration 14-5 (page 772).

Evermaster records the issuance of its bonds at a discount on January 1, 2014, as follows.

![]()

It records the first interest payment on July 1, 2014, and amortization of the discount as follows.

![]()

Evermaster records the interest expense accrued at December 31, 2014 (year-end), and amortization of the discount as follows.

![]()

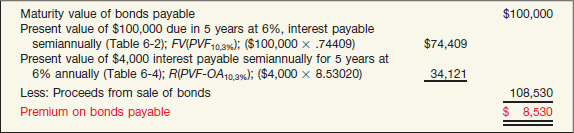

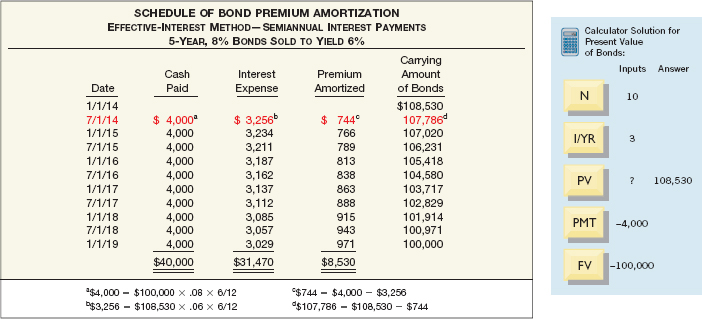

Bonds Issued at a Premium

Now assume that for the bond issue by Evermaster Corporation (page 771), investors are willing to accept an effective-interest rate of 6 percent. In that case, they would pay $108,530 or a premium of $8,530, computed as follows.

The five-year amortization schedule appears in Illustration 14-7.

Evermaster records the issuance of its bonds at a premium on January 1, 2014, as follows.

![]()

Evermaster records the first interest payment on July 1, 2014, and amortization of the premium as follows.

![]()

Evermaster should amortize the discount or premium as an adjustment to interest expense over the life of the bond in such a way as to result in a constant rate of interest when applied to the carrying amount of debt outstanding at the beginning of any given period.

Accruing Interest

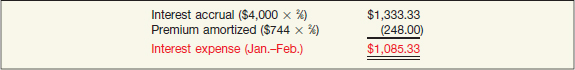

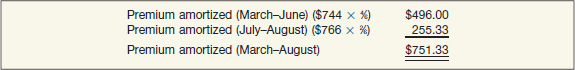

In our previous examples, the interest payment dates and the date the financial statements were issued were essentially the same. For example, when Evermaster sold bonds at a premium, the two interest payment dates coincided with the financial reporting dates. However, what happens if Evermaster wishes to report financial statements at the end of February 2014? In this case, the company prorates the premium by the appropriate number of months, to arrive at the proper interest expense, as follows.

Evermaster records this accrual as follows.

![]()

If the company prepares financial statements six months later, it follows the same procedure. That is, the premium amortized would be as follows.

The interest-accrual computation is much simpler if the company uses the straight-line method. For example, the total premium is $8,530, which Evermaster allocates evenly over the five-year period. Thus, premium amortization per month is $142.17 ($8,530 ÷ 60 months).

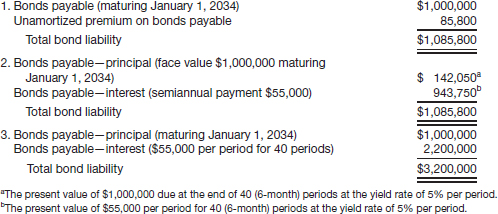

Classification of Discount and Premium

Discount on bonds payable is not an asset. It does not provide any future economic benefit. In return for the use of borrowed funds, a company must pay interest. A bond discount means that the company borrowed less than the face or maturity value of the bond. It therefore faces an actual (effective) interest rate higher than the stated (nominal) rate. Conceptually, discount on bonds payable is a liability valuation account. That is, it reduces the face or maturity amount of the related liability.5 This account is referred to as a contra account.

Similarly, premium on bonds payable has no existence apart from the related debt. The lower interest cost results because the proceeds of borrowing exceed the face or maturity amount of the debt. Conceptually, premium on bonds payable is a liability valuation account. It adds to the face or maturity amount of the related liability.6 This account is referred to as an adjunct account. As a result, companies report bond discounts and bond premiums as a direct deduction from or addition to the face amount of the bond.

Costs of Issuing Bonds

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

Because bond issue costs do not meet the definition of an asset, some argue they should be expensed at issuance.

The issuance of bonds involves engraving and printing costs, legal and accounting fees, commissions, promotion costs, and other similar charges. Companies are required to charge these costs to an asset account (usually long-term), often referred to as Unamortized Bond Issue Costs. Companies then allocate Unamortized Bond Issue Costs to expense over the life of the debt, in a manner similar to that used for discount on bonds. [2]

We disagree with this approach. Unamortized bond issue cost in our view is an expense (or a reduction of the related liability).

Apparently the FASB also disagrees with the current GAAP treatment and notes in Concepts Statement No. 6 that debt issue cost is not considered an asset because it provides no future economic benefit. The cost of issuing bonds, in effect, reduces the proceeds of the bonds issued and increases the effective-interest rate. Companies may thus account for it the same as the unamortized discount.

There is an obvious difference between GAAP and Concepts Statement No. 6's view of debt issue costs. However, until an issued standard supersedes existing GAAP, unamortized bond issue costs are treated as a deferred charge and amortized over the life of the debt.

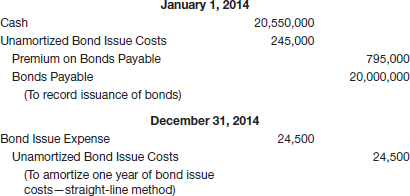

To illustrate the accounting for costs of issuing bonds, assume that Microchip Corporation sold $20,000,000 of 10-year debenture bonds for $20,795,000 on January 1, 2014 (also the date of the bonds). Costs of issuing the bonds were $245,000. Microchip records the issuance of the bonds and amortization of the bond issue costs as follows.

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS requires that issue costs reduce the carrying amount of the bond, which increases the effective-interest rate.

Microchip continues to amortize the bond issue costs in the same way over the life of the bonds. Although the effective-interest method is preferred, in practice companies may use the straight-line method to amortize bond issue costs because it is easier and the results are not materially different.

Extinguishment of Debt

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe the accounting for the extinguishment of debt.

How do companies record the payment of debt—often referred to as extinguishment of debt? If a company holds the bonds (or any other form of debt security) to maturity, the answer is straightforward: The company does not compute any gains or losses. It will have fully amortized any premium or discount and any issue costs at the date the bonds mature. As a result, the carrying amount will equal the maturity (face) value of the bond. As the maturity or face value will also equal the bond's fair value at that time, no gain or loss exists.

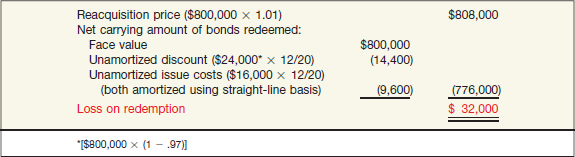

In some cases, a company extinguishes debt before its maturity date.7 The amount paid on extinguishment or redemption before maturity, including any call premium and expense of reacquisition, is called the reacquisition price. On any specified date, the net carrying amount of the bonds is the amount payable at maturity, adjusted for unamortized premium or discount, and cost of issuance. Any excess of the net carrying amount over the reacquisition price is a gain from extinguishment. The excess of the reacquisition price over the net carrying amount is a loss from extinguishment. At the time of reacquisition, the unamortized premium or discount, and any costs of issue applicable to the bonds, must be amortized up to the reacquisition date.

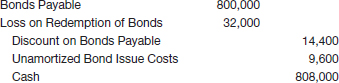

To illustrate, assume that on January 1, 2007, General Bell Corp. issued at 97 bonds with a par value of $800,000, due in 20 years. It incurred bond issue costs totaling $16,000. Eight years after the issue date, General Bell calls the entire issue at 101 and cancels it.8 At that time, the unamortized discount balance is $14,400, and the unamortized issue cost balance is $9,600. Illustration 14-10 indicates how General Bell computes the loss on redemption (extinguishment).

General Bell records the reacquisition and cancellation of the bonds as follows.

Note that it is often advantageous for the issuer to acquire the entire outstanding bond issue and replace it with a new bond issue bearing a lower rate of interest. The replacement of an existing issuance with a new one is called refunding. Whether the early redemption or other extinguishment of outstanding bonds is a nonrefunding or a refunding situation, a company should recognize the difference (gain or loss) between the reacquisition price and the net carrying amount of the redeemed bonds in income of the period of redemption.9

What do the numbers mean? YOUR DEBT IS KILLING MY EQUITY

Traditionally, investors in the equity and bond markets operate in their own separate worlds. However, in recent volatile markets, even quiet murmurs in the bond market have been amplified into movements (usually negative) in share prices. At one extreme, these gyrations heralded the demise of a company well before the investors could sniff out the problem.

The swift decline of Enron in late 2001 provided the ultimate lesson: A company with no credit is no company at all. As one analyst remarked, “You can no longer have an opinion on a company's shares without having an appreciation for its credit rating.” Indeed, other energy companies also felt the effect of Enron's troubles as lenders tightened or closed down the credit supply and raised interest rates on already-high levels of debt. The result? Stock prices took a hit.

Other industries are not immune from the negative shareholder effects of credit problems. For example, analysts at TheStreet.com compiled a list of companies with a focus on debt levels. Companies like Copel CIA (an energy distribution company) were rewarded with improved stock ratings, based on their manageable debt levels. In contrast, other companies with high debt levels and low ability to cover interest costs were not viewed very favorably. Among them is Goodyear Tire and Rubber, which reported debt six times greater than its equity.

Goodyear is a classic example of how swift and crippling a heavy debt-load can be. Not too long ago, Goodyear had a good credit rating and was paying a good dividend. But, with mounting operating losses, Goodyear's debt became a huge burden, its debt rating fell to junk status, the company cut its dividend, and its stock price dropped 80 percent. Only recently has Goodyear been able to dig out of its debt ditch. This was yet another example of stock prices taking a hit due to concerns about credit quality. Thus, even if your investment tastes are in equity, keep an eye on the liabilities.

Sources: Adapted from Steven Vames, “Credit Quality, Stock Investing Seem to Go Hand in Hand,” Wall Street Journal (April 1, 2002), p. R4; Herb Greenberg, “The Hidden Dangers of Debt,” Fortune (July 21, 2003), p. 153; and Christine Richard, “Holders of Corporate Bonds Seek Protection from Risk,” Wall Street Journal (December 17–18, 2005), p. B4.

LONG-TERM NOTES PAYABLE

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain the accounting for long-term notes payable.

The difference between current notes payable and long-term notes payable is the maturity date. As discussed in Chapter 13, short-term notes payable are those that companies expect to pay within a year or the operating cycle, whichever is longer. Long-term notes are similar in substance to bonds in that both have fixed maturity dates and carry either a stated or implicit interest rate. However, notes do not trade as readily as bonds in the organized public securities markets. Noncorporate and small corporate enterprises issue notes as their long-term instruments. Larger corporations issue both long-term notes and bonds.

Accounting for notes and bonds is quite similar. Like a bond, a note is valued at the present value of its future interest and principal cash flows. The company amortizes any discount or premium over the life of the note, just as it would the discount or premium on a bond.10 Companies compute the present value of an interest-bearing note, record its issuance, and amortize any discount or premium and accrual of interest in the same way that they do for bonds (as shown on pages 768–773 of this chapter).

As you might expect, accounting for long-term notes payable parallels accounting for long-term notes receivable as was presented in Chapter 7.

Notes Issued at Face Value

In Chapter 7, we discussed the recognition of a $10,000, three-year note Scandinavian Imports issued at face value to Bigelow Corp. In this transaction, the stated rate and the effective rate were both 10 percent. The time diagram and present value computation on page 360 of Chapter 7 (see Illustration 7-9) for Bigelow Corp. are the same for the issuer of the note, Scandinavian Imports, in recognizing a note payable. Because the present value of the note and its face value are the same, $10,000, Scandinavian recognizes no premium or discount. It records the issuance of the note as follows.

![]()

Scandinavian Imports recognizes the interest incurred each year as follows.

![]()

Notes Not Issued at Face Value

Zero-Interest-Bearing Notes

If a company issues a zero-interest-bearing (non-interest-bearing) note11 solely for cash, it measures the note's present value by the cash received. The implicit interest rate is the rate that equates the cash received with the amounts to be paid in the future. The issuing company records the difference between the face amount and the present value (cash received) as a discount and amortizes that amount to interest expense over the life of the note.

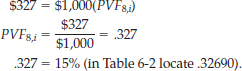

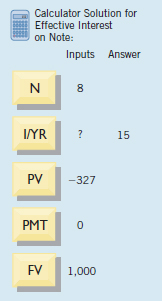

An example of such a transaction is Beneficial Corporation's offering of $150 million of zero-coupon notes (deep-discount bonds) having an eight-year life. With a face value of $1,000 each, these notes sold for $327—a deep discount of $673 each. The present value of each note is the cash proceeds of $327. We can calculate the interest rate by determining the rate that equates the amount the investor currently pays with the amount to be received in the future. Thus, Beneficial amortizes the discount over the eight-year life of the notes using an effective-interest rate of 15 percent.12

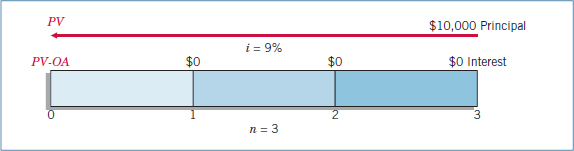

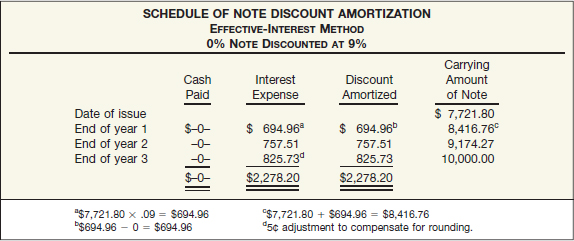

To illustrate the entries and the amortization schedule for a long-term note payable, assume that Turtle Cove Company issued the three-year, $10,000, zero-interest-bearing note to Jeremiah Company illustrated on page 361 of Chapter 7 (notes receivable). The implicit rate that equated the total cash to be paid ($10,000 at maturity) to the present value of the future cash flows ($7,721.80 cash proceeds at date of issuance) was 9 percent. (The present value of $1 for 3 periods at 9% is $0.77218.) Illustration 14-11 shows the time diagram for the single cash flow.

Turtle Cove records issuance of the note as follows.

![]()

Turtle Cove amortizes the discount and recognizes interest expense annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 14-12 shows the three-year discount amortization and interest expense schedule. (This schedule is similar to the note receivable schedule of Jeremiah Company in Illustration 7-12.)

Turtle Cove records interest expense at the end of the first year using the effective-interest method as follows.

![]()

The total amount of the discount, $2,278.20 in this case, represents the expense that Turtle Cove Company will incur on the note over the three years.

Interest-Bearing Notes

The zero-interest-bearing note above is an example of the extreme difference between the stated rate and the effective rate. In many cases, the difference between these rates is not so great.

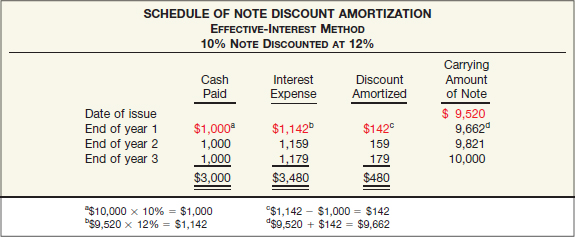

Consider the example from Chapter 7 where Marie Co. issued for cash a $10,000, three-year note bearing interest at 10 percent to Morgan Corp. The market rate of interest for a note of similar risk is 12 percent. Illustration 7-13 (page 362) shows the time diagram depicting the cash flows and the computation of the present value of this note. In this case, because the effective rate of interest (12%) is greater than the stated rate (10%), the present value of the note is less than the face value. That is, the note is exchanged at a discount. Marie Co. records the issuance of the note as follows.

![]()

Marie Co. then amortizes the discount and recognizes interest expense annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 14-13 shows the three-year discount amortization and interest expense schedule.

Marie Co. records payment of the annual interest and amortization of the discount for the first year as follows (amounts per amortization schedule).

![]()

When the present value exceeds the face value, Marie Co. exchanges the note at a premium. It does so by recording the premium as a credit and amortizing it using the effective-interest method over the life of the note as annual reductions in the amount of interest expense recognized.

Special Notes Payable Situations

Notes Issued for Property, Goods, or Services

Sometimes, companies may receive property, goods, or services in exchange for a note payable. When exchanging the debt instrument for property, goods, or services in a bargained transaction entered into at arm's length, the stated interest rate is presumed to be fair unless:

- No interest rate is stated, or

- The stated interest rate is unreasonable, or

- The stated face amount of the debt instrument is materially different from the current cash sales price for the same or similar items or from the current fair value of the debt instrument.

In these circumstances, the company measures the present value of the debt instrument by the fair value of the property, goods, or services or by an amount that reasonably approximates the fair value of the note. [5] If there is no stated rate of interest, the amount of interest is the difference between the face amount of the note and the fair value of the property.

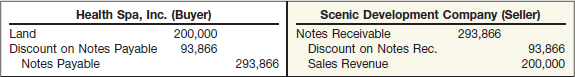

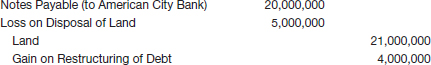

For example, assume that Scenic Development Company sells land having a cash sale price of $200,000 to Health Spa, Inc. In exchange for the land, Health Spa gives a five-year, $293,866, zero-interest-bearing note. The $200,000 cash sale price represents the present value of the $293,866 note discounted at 8 percent for five years. Should both parties record the transaction on the sale date at the face amount of the note, which is $293,866? No—if they did, Health Spa's Land account and Scenic's sales would be overstated by $93,866 (the interest for five years at an effective rate of 8%). Similarly, interest revenue to Scenic and interest expense to Health Spa for the five-year period would be understated by $93,866.

Because the difference between the cash sale price of $200,000 and the $293,866 face amount of the note represents interest at an effective rate of 8 percent, the companies' transaction is recorded at the exchange date as shown in Illustration 14-14.

During the five-year life of the note, Health Spa amortizes annually a portion of the discount of $93,866 as a charge to interest expense. Scenic Development records interest revenue totaling $93,866 over the five-year period by also amortizing the discount. The effective-interest method is required, unless the results obtained from using another method are not materially different from those that result from the effective-interest method.

Choice of Interest Rate

In note transactions, the effective or market interest rate is either evident or determinable by other factors involved in the exchange, such as the fair value of what is given or received. But, if a company cannot determine the fair value of the property, goods, services, or other rights, and if the note has no ready market, the problem of determining the present value of the note is more difficult. To estimate the present value of a note under such circumstances, a company must approximate an applicable interest rate that may differ from the stated interest rate. This process of interest-rate approximation is called imputation, and the resulting interest rate is called an imputed interest rate.

The prevailing rates for similar instruments of issuers with similar credit ratings affect the choice of a rate. Other factors such as restrictive covenants, collateral, payment schedule, and the existing prime interest rate also play a part. Companies determine the imputed interest rate when they issue a note; any subsequent changes in prevailing interest rates are ignored.

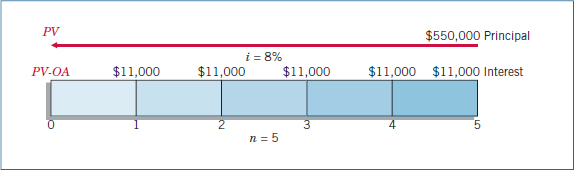

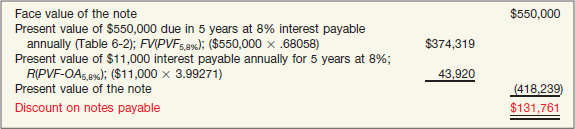

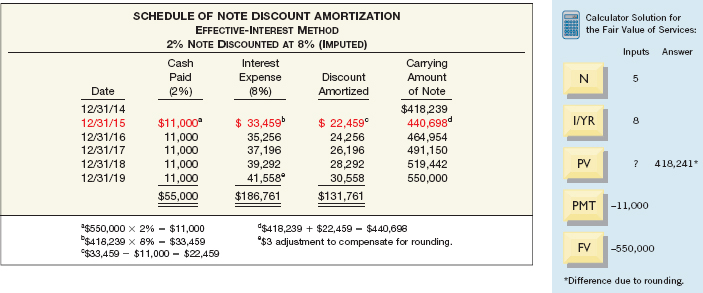

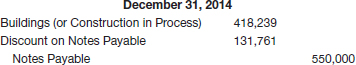

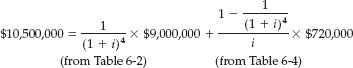

To illustrate, assume that on December 31, 2014, Wunderlich Company issued a promissory note to Brown Interiors Company for architectural services. The note has a face value of $550,000, a due date of December 31, 2019, and bears a stated interest rate of 2 percent, payable at the end of each year. Interest paid each period is therefore $11,000 ($550,000 × 2%). Wunderlich cannot readily determine the fair value of the architectural services, nor is the note readily marketable. On the basis of Wunderlich's credit rating, the absence of collateral, the prime interest rate at that date, and the prevailing interest on Wunderlich's other outstanding debt, the company imputes an 8 percent interest rate as appropriate in this circumstance. Illustration 14-15 shows the time diagram depicting both cash flows.

The present value of the note and the imputed fair value of the architectural services are determined as follows.

Wunderlich records issuance of the note in payment for the architectural services as follows.

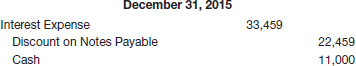

The five-year amortization schedule appears below.

Wunderlich records payment of the first year's interest and amortization of the discount as follows.

Mortgage Notes Payable

The most common form of long-term notes payable is a mortgage note payable. A mortgage note payable is a promissory note secured by a document called a mortgage that pledges title to property as security for the loan. Individuals, proprietorships, and partnerships use mortgage notes payable more frequently than do corporations. (As noted in the opening story, corporations usually find that bond issues offer advantages in obtaining large loans.)

The borrower usually receives cash for the face amount of the mortgage note. In that case, the face amount of the note is the true liability, and no discount or premium is involved. When the lender assesses “points,” however, the total amount received by the borrower is less than the face amount of the note.13 Points raise the effective-interest rate above the rate specified in the note. A point is 1 percent of the face of the note.

For example, assume that Harrick Co. borrows $1,000,000, signing a 20-year mortgage note with a stated interest rate of 10.75 percent as part of the financing for a new plant. If Associated Savings demands 4 points to close the financing, Harrick will receive 4 percent less than $1,000,000—or $960,000—but it will be obligated to repay the entire $1,000,000 at the rate of $10,150 per month. Because Harrick received only $960,000, and must repay $1,000,000, its effective-interest rate is increased to approximately 11.3 percent on the money actually borrowed.

On the balance sheet, Harrick should report the mortgage note payable as a liability using a title such as “Mortgage Payable” or “Notes Payable—Secured,” with a brief disclosure of the property pledged in notes to the financial statements.

Mortgages may be payable in full at maturity or in installments over the life of the loan. If payable at maturity, Harrick classifies its mortgage payable as a long-term liability on the balance sheet until such time as the approaching maturity date warrants showing it as a current liability. If it is payable in installments, Harrick shows the current installments due as current liabilities, with the remainder as a long-term liability.

Lenders have partially replaced the traditional fixed-rate mortgage with alternative mortgage arrangements. Most lenders offer variable-rate mortgages (also called floating-rate or adjustable-rate mortgages) featuring interest rates tied to changes in the fluctuating market rate. Generally, the variable-rate lenders adjust the interest rate at either one- or three-year intervals, pegging the adjustments to changes in the prime rate or the U.S. Treasury bond rate.

Fair Value Option

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe the accounting for the fair value option.

As indicated earlier, noncurrent liabilities, such as bonds and notes payable, are generally measured at amortized cost (face value of the payable, adjusted for any payments and amortization of any premium or discount). However, companies have the option to record fair value in their accounts for most financial assets and liabilities, including bonds and notes payable. [6] As discussed in Chapter 7 (page 365), the FASB believes that fair value measurement for financial instruments, including financial liabilities, provides more relevant and understandable information than amortized cost. It considers fair value to be more relevant because it reflects the current cash equivalent value of financial instruments.

Fair Value Measurement

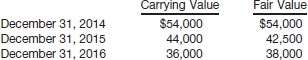

If companies choose the fair value option, noncurrent liabilities, such as bonds and notes payable, are recorded at fair value, with unrealized holding gains or losses reported as part of net income. An unrealized holding gain or loss is the net change in the fair value of the liability from one period to another, exclusive of interest expense recognized but not recorded. As a result, the company reports the liability at fair value each reporting date. In addition, it reports the change in value as part of net income.

To illustrate, Edmonds Company has issued $500,000 of 6 percent bonds at face value on May 1, 2014. Edmonds chooses the fair value option for these bonds. At December 31, 2014, the value of the bonds is now $480,000 because interest rates in the market have increased to 8 percent. The value of the debt securities falls because the bond is paying less than market rate for similar securities. Under the fair value option, Edmonds makes the following entry.

![]()

As the journal entry indicates, the value of the bonds declined. This decline leads to a reduction in the bond liability and a resulting unrealized holding gain, which is reported as part of net income. The value of Edmonds' debt declined because interest rates increased. It should be emphasized that Edmonds must continue to value the bonds payable at fair value in all subsequent periods.

Fair Value Controversy

With the Edmonds bonds, we assumed that the decline in value of the bonds was due to an interest rate increase. In other situations, the decline may occur because the bonds become more likely to default. That is, if the creditworthiness of Edmonds Company declines, the value of its debt also declines. If its creditworthiness declines, its bond investors are receiving a lower rate relative to investors with similar-risk investments. If Edmonds is using the fair value option, changes in the fair value of the bonds payable for a decline in creditworthiness are included as part of income. Some question how Edmonds can record a gain when its creditworthiness is becoming worse. As one writer noted, “It seems counterintuitive.” However, the FASB notes that the debtholders' loss is the shareholders' gain. That is, the shareholders' claims on the assets of the company increase when the value of the debtholders' claims declines. In addition, the worsening credit position may indicate that the assets of the company are declining in value as well. Thus, the company may be reporting losses on the asset side, which will be offsetting gains on the liability side.14

REPORTING AND ANALYZING LIABILITIES

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain the reporting of off-balance-sheet financing arrangements.

Reporting liabilities and long-term debt is one of the most controversial areas in financial reporting. Because long-term debt has a significant impact on the cash flows of the company, reporting requirements must be substantive and informative. One problem is that the definition of a liability established in Concepts Statement No. 6 and the recognition criteria established in Concepts Statement No. 5 are sufficiently imprecise that some continue to argue that certain obligations need not be reported as debt.

Off-Balance-Sheet Financing

What do Krispy Kreme, Cisco, Enron, and Adelphia Communications have in common? They all have been accused of using off-balance-sheet financing to minimize the reporting of debt on their balance sheets. Off-balance-sheet financing is an attempt to borrow monies in such a way to prevent recording the obligations. It has become an issue of extreme importance. Many allege that Enron, in one of the largest corporate failures on record, hid a considerable amount of its debt off the balance sheet. As a result, any company that uses off-balance-sheet financing today risks investors dumping the company's stock. Consequently, the company's share price will suffer. Nevertheless, a considerable amount of off-balance-sheet financing continues to exist. As one writer noted, “The basic drives of humans are few: to get enough food, to find shelter, and to keep debt off the balance sheet.”

Different Forms

Off-balance-sheet financing can take many different forms:

- Non-consolidated subsidiary. Under GAAP, a parent company does not have to consolidate a subsidiary company that is less than 50 percent owned. In such cases, the parent therefore does not report the assets and liabilities of the subsidiary. All the parent reports on its balance sheet is the investment in the subsidiary. As a result, users of the financial statements may not understand that the subsidiary has considerable debt for which the parent may ultimately be liable if the subsidiary runs into financial difficulty.

- Special-purpose entity (SPE). A company creates a special-purpose entity (SPE) to perform a special project. To illustrate, assume that Clarke Company decides to build a new factory. However, management does not want to report the plant or the borrowing used to fund the construction on its balance sheet. It therefore creates an SPE, the purpose of which is to build the plant. (This arrangement is called a project financing arrangement.) The SPE finances and builds the plant. In return, Clarke guarantees that it or some outside party will purchase all the products produced by the plant. (Some refer to this as a take-or-pay contract.) As a result, Clarke might not report the asset or liability on its books. The accounting rules in this area are complex. We discuss the accounting for SPEs in Appendix 17B.

- Operating leases. Another way that companies keep debt off the balance sheet is by leasing. Instead of owning the assets, companies lease them. Again, by meeting certain conditions, the company has to report only rent expense each period and to provide note disclosure of the transaction. Note that SPEs often use leases to accomplish off-balance-sheet treatment. We discuss accounting for lease transactions extensively in Chapter 21.

Rationale

Why do companies engage in off-balance-sheet financing? A major reason is that many believe that removing debt enhances the quality of the balance sheet and permits credit to be obtained more readily and at less cost.

Second, loan covenants often limit the amount of debt a company may have. As a result, the company uses off-balance-sheet financing because these types of commitments might not be considered in computing the debt limitation.

Third, some argue that the asset side of the balance sheet is severely understated. For example, companies that use LIFO costing for inventories and depreciate assets on an accelerated basis will often have carrying amounts for inventories and property, plant, and equipment that are much lower than their fair values. As an offset to these lower values, some believe that part of the debt does not have to be reported. In other words, if companies report assets at fair values, less pressure would undoubtedly exist for off-balance-sheet financing arrangements.

Whether the arguments above have merit is debatable. The general idea of “out of sight, out of mind” may not be true in accounting. Many users of financial statements indicate that they factor these off-balance-sheet financing arrangements into their computations when assessing debt-to-equity relationships. Similarly, many loan covenants also attempt to account for these complex arrangements. Nevertheless, many companies still believe that benefits will accrue if they omit certain obligations from the balance sheet.

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

There is no comparable institution to the SEC in international securities markets. As a result, many international companies (those not registered with the SEC) are not required to provide disclosures such as those related to contractual obligations.

As a response to off-balance-sheet financing arrangements, the FASB has increased disclosure (note) requirements. This response is consistent with an “efficient markets” philosophy: The important question is not whether the presentation is off-balance-sheet or not, but whether the items are disclosed at all. In addition, the SEC, in response to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, now requires companies to provide related information in their management discussion and analysis sections. Specifically, companies must disclose (1) all contractual obligations in a tabular format and (2) contingent liabilities and commitments in either a textual or tabular format.15

We believe that recording more obligations on the balance sheet will enhance financial reporting. Given the problems with companies such as Enron, Dynegy, Williams Company, Chesapeake Energy, and Calpine, and the Sarbanes-Oxley requirements, we expect that less off-balance-sheet financing will occur in the future.

What do the numbers mean? OBLIGATED

The off-balance-sheet world is slowly but surely becoming more on-balance-sheet. New interpretations on guarantees (discussed in Chapter 13) and variable-interest entities (discussed in Appendix 17B) are doing their part to increase the amount of debt reported on corporate balance sheets.

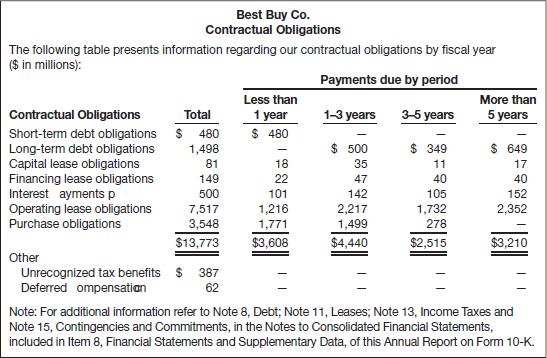

In addition, the SEC has rules that require companies to disclose off-balance-sheet arrangements and contractual obligations that currently have, or are reasonably likely to have, a material future effect on the companies' financial condition. Companies now must include a tabular disclosure (following a prescribed format) in the management discussion and analysis section of the annual report. Presented below is Best Buy Co.'s tabular disclosure of its contractual obligations.

Enron's abuse of off-balance-sheet financing to hide debt was shocking and inappropriate. One silver lining in the Enron debacle, however, is that the standard-setting bodies in the accounting profession are now providing increased guidance on companies' reporting of contractual obligations. We believe the new SEC rule, which requires companies to report their obligations over a period of time, will be extremely useful to the investment community.

Presentation and Analysis of Long-Term Debt

Presentation of Long-Term Debt

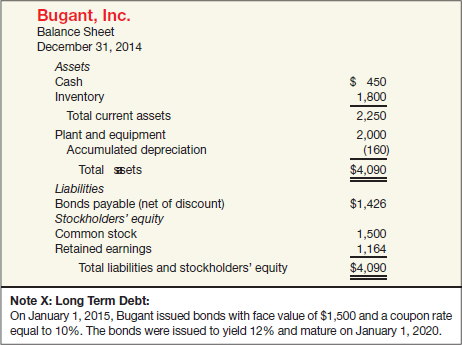

Companies that have large amounts and numerous issues of long-term debt frequently report only one amount in the balance sheet, supported with comments and schedules in the accompanying notes. Long-term debt that matures within one year should be reported as a current liability, unless using noncurrent assets to accomplish redemption. If the company plans to refinance debt, convert it into stock, or retire it from a bond retirement fund, it should continue to report the debt as noncurrent. However, the company should disclose the method it will use in its liquidation. [7], [8]

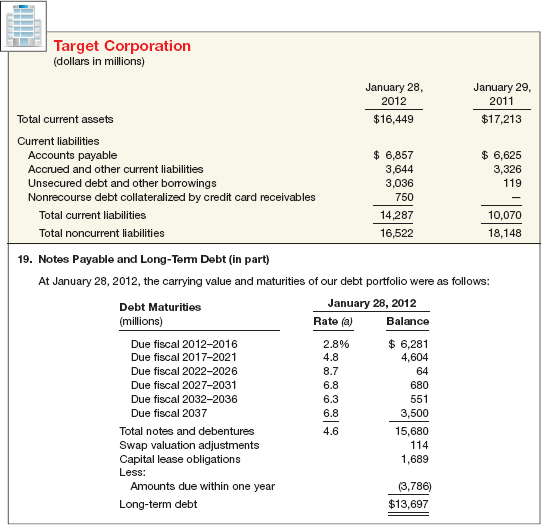

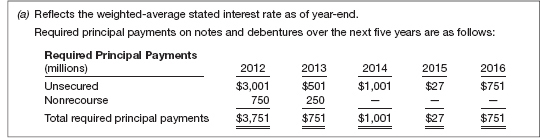

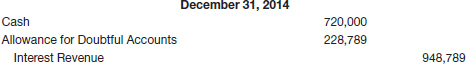

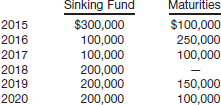

Note disclosures generally indicate the nature of the liabilities, maturity dates, interest rates, call provisions, conversion privileges, restrictions imposed by the creditors, and assets designated or pledged as security. Companies should show any assets pledged as security for the debt in the assets section of the balance sheet. The fair value of the long-term debt should also be disclosed if it is practical to estimate fair value. Finally, companies must disclose future payments for sinking fund requirements and maturity amounts of long-term debt during each of the next five years. These disclosures aid financial statement users in evaluating the amounts and timing of future cash flows. Illustration 14-18 shows an example of the type of information provided for Target Corporation. Note that if the company has any off-balance-sheet financing, it must provide extensive note disclosure. [9]

Analysis of Long-Term Debt

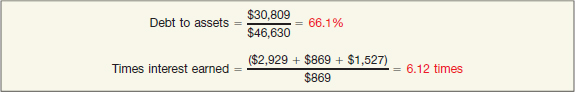

Long-term creditors and stockholders are interested in a company's long-run solvency, particularly its ability to pay interest as it comes due and to repay the face value of the debt at maturity. Debt to assets and times interest earned are two ratios that provide information about debt-paying ability and long-run solvency.

Debt to Assets. The debt to assets ratio measures the percentage of the total assets provided by creditors. To compute it, divide total debt (both current and long-term liabilities) by total assets, as Illustration 14-19 shows.

The higher the percentage of total liabilities to total assets, the greater the risk that the company may be unable to meet its maturing obligations.

Times Interest Earned. The times interest earned ratio indicates the company's ability to meet interest payments as they come due. As shown in Illustration 14-20, it is computed by dividing income before interest expense and income taxes by interest expense.

![]() You will want to read the IFRS INSIGHTS on pages 815–819 for discussion of IFRS related to long-term liabilities.

You will want to read the IFRS INSIGHTS on pages 815–819 for discussion of IFRS related to long-term liabilities.

To illustrate these ratios, we use data from Target's 2011 annual report. Target has total liabilities of $30,809 million, total assets of $46,630 million, interest expense of $869 million, income taxes of $1,527 million, and net income of $2,929 million. We compute Target's debt to assets and times interest earned ratios as shown in Illustration 14-21.

Even though Target has a relatively high debt to assets percentage of 66.1 percent, its interest coverage of 6.12 times indicates it can easily meet its interest payments as they come due.

Evolving Issue FAIR VALUE OF LIABILITIES: PICK A NUMBER, ANY NUMBER

Evolving Issue FAIR VALUE OF LIABILITIES: PICK A NUMBER, ANY NUMBER

In 2011, Citigroup's third-quarter earnings rose 68 percent from a year earlier, partly due to an accounting adjustment. The accounting adjustment was a $1.9 billion gain related to a change in the valuation of its debt obligations. A similar situation resulted in the third quarter of 2011 for JPMorgan. Its results were enhanced by decreasing the value of its debt, also by $1.9 billion. How does a company recognize a gain on its debt when it has not sold it?

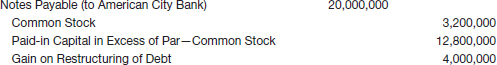

Here is how it works. Say a company records a $100 million liability for bonds it issues. Subsequently, the bond's credit rating drops from AA to BB. As a result, the price of the bond trading in the market drops to $90 million. As we discussed earlier, if the fair value option is used to value debt, the company makes the following entry.

![]()

Presto! The company's net income increases even though its credit rating drops. This result seems counterintuitive—how does a company that is actually doing worse have its income increase?

The FASB has struggled with this issue for years. It defends the present position by indicating that the valuation of a liability is related to its credit standing. Therefore, if a company's credit standing drops, the liability value drops as well. And if the value of a company's liability is less, the company is better off and should record a gain. It should be noted that it can work the other way as well. That is, if a company's credit standing increases, the value of the liability increases and therefore the company records a loss.

Another major argument in favor of the present approach is that by forcing companies to highlight their credit weakness, it raises a question about the asset side of the balance sheet. In other words, if you see a credit weakness, you should ask, “Where is the impaired asset?” If a company's credit is bad, it may mean there are losses on the asset side that are not being recognized or disclosed.

The FASB (and IASB) are debating this issue in the financial instruments project. Some have suggested that the gain or loss be part of other comprehensive income. Others disagree and believe it should be part of net income. Still others believe that changes in the value of the liability should not be reported in income until the liability is extinguished. As one expert noted, “At its worse, bank accounting can seem like the mirrors in a fun house. Reality is reflected, but the distortions can be very large.”

Sources: Floyd Norris, “Distortions in Baffling Financial Statements,” The New York Times (November 10, 2011); and Marie Leone, “The Fair Value Deadbeat Debate Returns,” CFO.com (June 25, 2009).

KEY TERMS

bearer (coupon) bonds, 765

bond discount, 767

bond indenture, 764

bond premium, 767

callable bonds, 765

carrying value, 770

commodity-backed bonds, 765

convertible bonds, 765

debenture bonds, 765

debt to assets ratio, 787

deep-discount (zero-interest debenture) bonds, 765

discount, 767

effective-interest method, 770

effective yield, or market rate, 767

extinguishment of debt, 775

face, par, principal, or maturity value, 766

fair value option, 782

imputation, 780

imputed interest rate, 780

income bonds, 765

long-term debt, 764

long-term notes payable, 776

mortgage notes payable, 782

off-balance-sheet financing, 783

premium, 767

refunding, 776

registered bonds, 765

revenue bonds, 765

secured bonds, 765

serial bonds, 765

special-purpose entity (SPE), 784

stated, coupon, or nominal rate, 766

straight-line method, 769

term bonds, 765

times interest earned, 787

zero-interest debenture bonds, 765

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES

![]() Describe the formal procedures associated with issuing long-term debt. Incurring long-term debt is often a formal procedure. The bylaws of corporations usually require approval by the board of directors and the stockholders before corporations can issue bonds or can make other long-term debt arrangements. Generally, long-term debt has various covenants or restrictions. The covenants and other terms of the agreement between the borrower and the lender are stated in the bond indenture or note agreement.

Describe the formal procedures associated with issuing long-term debt. Incurring long-term debt is often a formal procedure. The bylaws of corporations usually require approval by the board of directors and the stockholders before corporations can issue bonds or can make other long-term debt arrangements. Generally, long-term debt has various covenants or restrictions. The covenants and other terms of the agreement between the borrower and the lender are stated in the bond indenture or note agreement.

![]() Identify various types of bond issues. Various types of bond issues are (1) secured and unsecured bonds; (2) term, serial, and callable bonds; (3) convertible, commodity-backed, and deep-discount bonds; (4) registered and bearer (coupon) bonds; and (5) income and revenue bonds. The variety in the types of bonds results from attempts to attract capital from different investors and risk-takers and to satisfy the cash flow needs of the issuers.

Identify various types of bond issues. Various types of bond issues are (1) secured and unsecured bonds; (2) term, serial, and callable bonds; (3) convertible, commodity-backed, and deep-discount bonds; (4) registered and bearer (coupon) bonds; and (5) income and revenue bonds. The variety in the types of bonds results from attempts to attract capital from different investors and risk-takers and to satisfy the cash flow needs of the issuers.

![]() Describe the accounting valuation for bonds at date of issuance. The investment community values a bond at the present value of its future cash flows, which consist of interest and principal. The rate used to compute the present value of these cash flows is the interest rate that provides an acceptable return on an investment commensurate with the issuer's risk characteristics. The interest rate written in the terms of the bond indenture and ordinarily appearing on the bond certificate is the stated, coupon, or nominal rate. The issuer of the bonds sets the rate and expresses it as a percentage of the face value (also called the par value, principal amount, or maturity value) of the bonds. If the rate employed by the buyers differs from the stated rate, the present value of the bonds computed by the buyers will differ from the face value of the bonds. The difference between the face value and the present value of the bonds is either a discount or premium.

Describe the accounting valuation for bonds at date of issuance. The investment community values a bond at the present value of its future cash flows, which consist of interest and principal. The rate used to compute the present value of these cash flows is the interest rate that provides an acceptable return on an investment commensurate with the issuer's risk characteristics. The interest rate written in the terms of the bond indenture and ordinarily appearing on the bond certificate is the stated, coupon, or nominal rate. The issuer of the bonds sets the rate and expresses it as a percentage of the face value (also called the par value, principal amount, or maturity value) of the bonds. If the rate employed by the buyers differs from the stated rate, the present value of the bonds computed by the buyers will differ from the face value of the bonds. The difference between the face value and the present value of the bonds is either a discount or premium.

![]() Apply the methods of bond discount and premium amortization. The discount (premium) is amortized and charged (credited) to interest expense over the life of the bonds. Amortization of a discount increases bond interest expense, and amortization of a premium decreases bond interest expense. The profession's preferred procedure for amortization of a discount or premium is the effective-interest method. Under the effective-interest method, (1) bond interest expense is computed by multiplying the carrying value of the bonds at the beginning of the period by the effective-interest rate; then, (2) the bond discount or premium amortization is determined by comparing the bond interest expense with the interest to be paid.

Apply the methods of bond discount and premium amortization. The discount (premium) is amortized and charged (credited) to interest expense over the life of the bonds. Amortization of a discount increases bond interest expense, and amortization of a premium decreases bond interest expense. The profession's preferred procedure for amortization of a discount or premium is the effective-interest method. Under the effective-interest method, (1) bond interest expense is computed by multiplying the carrying value of the bonds at the beginning of the period by the effective-interest rate; then, (2) the bond discount or premium amortization is determined by comparing the bond interest expense with the interest to be paid.

![]() Describe the accounting for the extinguishment of debt. At the time of extinguishment (reacquisition, redemption, or refunding) of long-term debt, the unamortized premium or discount and any costs of issue applicable to the debt must be amortized up to the reacquisition date. The reacquisition price is the amount paid on extinguishment or redemption before maturity, including any call premium and expense of reacquisition. On any specified date, the net carrying amount of the debt is the amount payable at maturity, adjusted for unamortized premium or discount and issue costs. Any excess of the net carrying amount over the reacquisition price is a gain from extinguishment. The excess of the reacquisition price over the net carrying amount is a loss from extinguishment. Gains and losses on extinguishments are recognized currently in income.

Describe the accounting for the extinguishment of debt. At the time of extinguishment (reacquisition, redemption, or refunding) of long-term debt, the unamortized premium or discount and any costs of issue applicable to the debt must be amortized up to the reacquisition date. The reacquisition price is the amount paid on extinguishment or redemption before maturity, including any call premium and expense of reacquisition. On any specified date, the net carrying amount of the debt is the amount payable at maturity, adjusted for unamortized premium or discount and issue costs. Any excess of the net carrying amount over the reacquisition price is a gain from extinguishment. The excess of the reacquisition price over the net carrying amount is a loss from extinguishment. Gains and losses on extinguishments are recognized currently in income.

![]() Explain the accounting for long-term notes payable. Accounting procedures for notes and bonds are similar. Like a bond, a note is valued at the present value of its expected future interest and principal cash flows, with any discount or premium being similarly amortized over the life of the note. Whenever the face amount of the note does not reasonably represent the present value of the consideration in the exchange, a company must evaluate the entire arrangement in order to properly record the exchange and the subsequent interest.

Explain the accounting for long-term notes payable. Accounting procedures for notes and bonds are similar. Like a bond, a note is valued at the present value of its expected future interest and principal cash flows, with any discount or premium being similarly amortized over the life of the note. Whenever the face amount of the note does not reasonably represent the present value of the consideration in the exchange, a company must evaluate the entire arrangement in order to properly record the exchange and the subsequent interest.

![]() Describe the accounting for the fair value option. Companies have the option to record fair value in their accounts for most financial assets and liabilities, including noncurrent liabilities. Fair value measurement for financial instruments, including financial liabilities, provides more relevant and understandable information than amortized cost. If companies choose the fair value option, noncurrent liabilities, such as bonds and notes payable, are recorded at fair value, with unrealized holding gains or losses reported as part of net income. An unrealized holding gain or loss is the net change in the fair value of the liability from one period to another, exclusive of interest expense recognized but not recorded.

Describe the accounting for the fair value option. Companies have the option to record fair value in their accounts for most financial assets and liabilities, including noncurrent liabilities. Fair value measurement for financial instruments, including financial liabilities, provides more relevant and understandable information than amortized cost. If companies choose the fair value option, noncurrent liabilities, such as bonds and notes payable, are recorded at fair value, with unrealized holding gains or losses reported as part of net income. An unrealized holding gain or loss is the net change in the fair value of the liability from one period to another, exclusive of interest expense recognized but not recorded.

![]() Explain the reporting of off-balance-sheet financing arrangements. Off-balance-sheet financing is an attempt to borrow funds in such a way to prevent recording obligations. Examples of off-balance-sheet arrangements are (1) non-consolidated subsidiaries, (2) special-purpose entities, and (3) operating leases.

Explain the reporting of off-balance-sheet financing arrangements. Off-balance-sheet financing is an attempt to borrow funds in such a way to prevent recording obligations. Examples of off-balance-sheet arrangements are (1) non-consolidated subsidiaries, (2) special-purpose entities, and (3) operating leases.