Chapter 4

Analysis of Audiovisual Expression 1

4.1. Introduction

The analysis of audiovisual expression constitutes a particular approach to the processing of audio and visual information from our audiovisual text. In this approach, the focus of attention is still the text’s “semantic content” and the meaning it conveys, but now the analysis deals with the visual and sound representations of this meaning and on the technical processes which facilitate this representation.

There are varying definitions of the notion of an audiovisual shot1 which will not be discussed at length here. Generally, it is helpful to distinguish the image track from the soundtrack, both of which constitute a “logical manifestation of the modes of expression” [STO 03; STO 09]. Thus the audiovisual expression is a composite phenomenon that must be discussed on two different levels:

– the visual shot;

– the sound shot.

In this chapter, we shall address the two very particular aspects of analysis and development of the audiovisual shot, namely describing the analysis of the visual shot and describing the analysis of the sound shot.

4.2. Analysis of the visual shot

4.2.1. General overview

As we saw in the previous chapter, the Description Workshop facilitates an analysis of the video based on the semiotics of the audiovisual document.2 Hence, in order to develop the appropriate model of description to analyze the visual elements, we relied upon the main processes of semiotic visual analysis of film texts. The visual shot is composed of images, in the same way that a sentence is made of words. In this sense, it is polysemic, like a sentence. The image is therefore a visual text and as such may be described, analyzed, contextualized and finally, interpreted.3

The notion of thematic isotopy developed by Greimas [GRE 66; GRE 79], is essential to our approach. It stresses the importance of the recurrence of the themes and thematic configurations existing within an audiovisual document. Any audiovisual document is a whole which may be broken down, similarly to a text lato sensu, into a number of units.

It is therefore necessary for the analyst to be able to identify, name and contextualize these units. In order to do so, he will have to:

– recognize the set of objects presented on the images;

– virtually select them;

– explicitize them by naming them;

– comment upon them, if need be, so as to contextualize them;

– be aware of their function; and finally;

– identify the techniques used to arrange these objects and create these images.

All of these requirements are taken into consideration in the interactive working form (in the ASW Description Workshop environment) which can be accessed via the “visual shot” tab. This enables the analyst to take account of the whole “story” which takes place in the video, by identifying people, places, décor … essentially all the “thematic visual objects” which convey meaning in our project of analysis. It also takes account of the “functional visual objects”, i.e. those which are introduced into the visual shot to serve a particular purpose in processing the meaning. Finally, each time one of these objects is identified, one or more visual techniques may be selected and specified.

The analysis of the visual shot of the description of a video is more or less relevant depending on the filmic genre of the video being analyzed. It is understood that visually analyzing an interview or series of seminars will be “concise” in terms of details and “less significant” in terms of technical processes, than analyzing the visual shot of a documentary film or a report in which the staged objects and the functional and technical processes are more deliberately worked. The objectives are not the same. Therefore, during the analysis, depending on the filmic genre, a choice will have to be made between, (a) carrying out a detailed description at the thematic level (that is, the level of discourse), only noting a few audiovisual features – visual bookmarks, so to speak – mainly made of a recognition of the actors involved; and (b) a detailed description of the visual and/or sound shots, which may in some cases be accompanied by a more or less systematic thematic description.

In any case, a contextualized marking of the “visual objects” proves highly interesting to anyone needing information about the images or the processing of them, about the visual apprehension of a particular subject, or about the representations and effects of the constructed images on a given topic.

4.2.2. General description of the visual shot and analysis procedures

The analysis of the visual shot of a chosen audiovisual object obviously comprises a restriction, in the sense that the analysis does not deal with a still image and therefore of a selected shot (in this version, it is not possible to make a freeze-frame and analyze a specific still image). The analysis is effected either on the entirety of the video (all filmic shots), or a chosen segment, itself made up of a set of audiovisual shots. Therefore, and in the same way as for analyzing the thematic level (see Chapter 5), the visual shot may be described either at the level of the video itself or at the level of each of the segments of the video.4 Once again, the choice is free and depends on the analyst’s objectives.

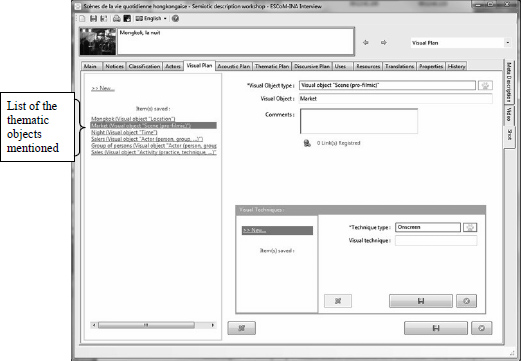

Figure 4.1 presents the structure of the scheme for describing the visual shot and access to the two associated forms:

– “Type of visual object”;

– “Visual techniques”.

These forms offer the analyst a twofold possibility:

– identifying a number of objects making up the pro-filmic situation, by way of chosen sequential shots, and identifying the different techniques used in valorizing these objects, or;

– identifying the objects without specifying the visual techniques used in their creation.

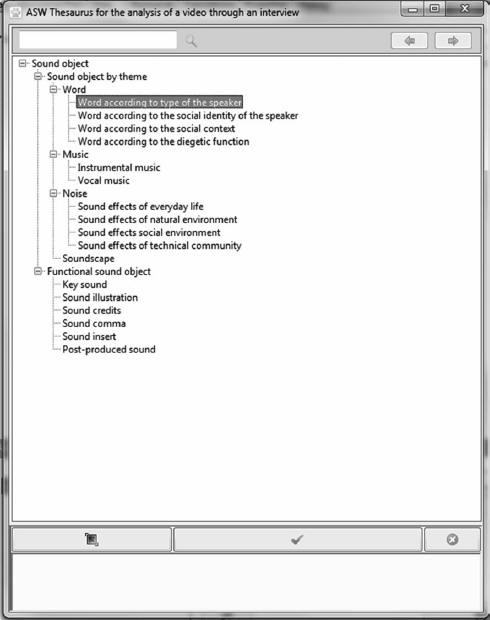

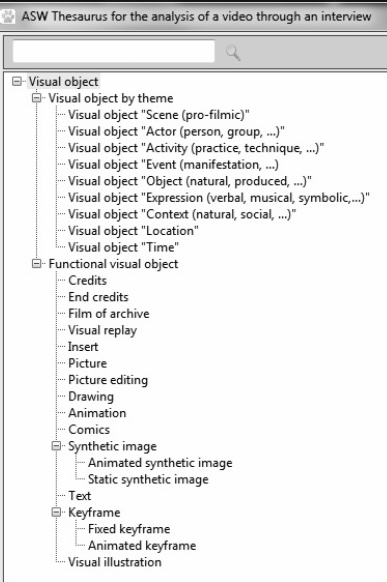

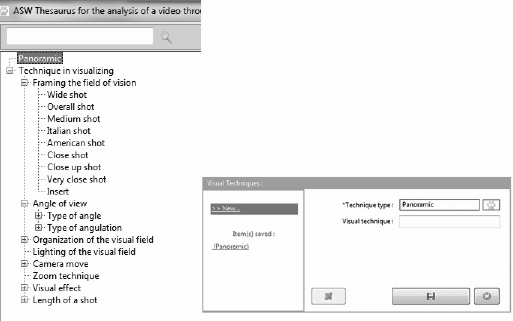

In both cases, once we have “virtually” selected a visual object in our sequential shot (the segment), the first thing we have to do is to assign an appropriate term it. This term is selected from a thesaurus listing the predefined terms referring to thematic objects, functional objects (Figure 4.2) and visual techniques (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.1. Overall view of the “visual shot” subsection in the description workshop

The terms referring to the thematic objects provide us with information about the intrinsic nature of the objects placed in shot – enabling us to describe each separate element that makes up those images (people, objects, actions, places) – but also about their thematization (e.g. expressive, event-based, temporal, etc….).

The terms referring to the functional objects provide us with information about their use within the text: credits, inserts, animation, etc.

Following this initial attribution, and as we can see in Figure 4.1, the “Type of visual object” form offers two free fields to be filled in, entitled Visual object and Comment. These serve to name the objects and comment upon them if the need arises.

Figure 4.2. View of the ASW thesaurus for analysis of a video, “types of visual objects”

The terms referring to the “Type of visual technique” (Figure 4.3) correspond to the main items of the technical analysis of the image: scale of shots (framing), camera angles, organization of the visual field, lighting, camera movement, visual effect and duration of the visual shot.

Again, once a “type of technique” has been selected, a free field, “Visual technique”, offers us the possibility of providing additional details regarding the techniques used.

Figure 4.3. View of the ASW thesaurus and schema available for analyzing the “visual techniques” used

4.2.3. Examples of describing the visual shot of an audiovisual text

As has already been said, it seems less relevant to describe the visual shots of a filmic genre such as an interview, in the sense that the camera remains static. However it may be interesting, for certain research projects – particularly about visual semiology – or for specific categories of students, e.g. on cinematography and film-making techniques courses, to be able to decipher the techniques used during the direction and editing of an interview.

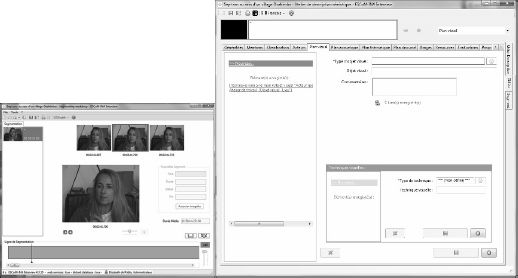

4.2.3.1. The visual shot of an interview

Our example will be an interview with an anthropologist carried out at her home, in her work studio.5 To begin with, the shooting conditions are extremely restrictive: the room is very narrow and full of materials; the cameraman has almost no room to move. However the footage – as it appears in the edited montage – is fluid: the editor was able to alternate between long shots and close-ups of the interviewee, which gives the impression of interactive dialog and provides a certain degree of dynamism when watching the interview.

Now, let us see how to analyze the visual shot at the level of the entire video so as to formalize these impressions. The interview can be broken down into relatively simple visual shots – a series of close-ups (of varying degrees of extremity) on the researcher, and wider shots showing the interviewer’s back and different elements of the anthropologist’s workplace.

The suggested schemas enable us to exactly point out the thematic objects and the visual techniques used in this video by selecting two thematic objects which are relevant in processing the interview – and, generally speaking, for any interview): the main actor and the setting. Associating a visual technique with them enables us to reinforce their role in the interview. For example, we used close-ups, zooms and the foreground for the researcher (i.e. the most important element in interviewing a person), and long shots together with the background to contextualize the place of filming.

A purely visual and technical comparison between different interviews could prove enriching for anyone wishing to study this form of filmmaking.

Figure 4.4. View of the single segmentation shot used in the complete analysis of the non-segmented video, with regard to the visual shot

4.2.3.2. The visual shot of a road-movie

Let us now take an example which is opposite to the interview genre: the analysis of the visual shot of a road-movie. Visual and sound shots are essential in this genre, which relies almost entirely on the strength of the images and the pairing of image and sound. To this end, we have selected a document made up of short sequences intended to show different aspects of daily life in Hong Kong.6 This document is particularly rich in visual and sound information exemplifying a few extremely localized aspects of life in the megalopolis of Hong Kong. It advances a vision of daily life which often seems culturally distant from the Western one. Here, it is impossible to make a generalized description; the text must be segmented – firstly to carry out a subsequent thematic analysis, dealing with the main topics addressed by these sequences, and secondly to facilitate a detailed analysis of the visual and sound shots.

Figure 4.5. View of the segmentation carried out in order to analyze the road-movie, “the city of Hong Kong”

In Figure 4.5, note the significant degree of segmentation. Here let us consider a few scenes showing the discovery of open public spaces: markets. We shall focus on the following segments respectively:

– segment 4, entitled “Mongkok, night-time market”;

– segment 8, entitled “open market”;

– segment 10, entitled “fish market”;

– segment 16, entitled “flea market”.

The topic of markets is an interesting one for study on a number of counts: it enables us to analyze the means of trading, the social relationships between potential clients and the vendors but also between the vendors, their motives, and the organization of a whole typology of markets in a localized social space. A detailed visual analysis will enable us to visually pinpoint: what types of markets we are dealing with (flea markets, food markets, tourist markets, night-time markets …), what type of products are on offer (clothes, animals, fruit and vegetables, bric-a-brac …), where they are located in the city (city center, outskirts, shopping malls, tourist centers).

Figure 4.6. View of the visual analysis of segment 4,“Mongkok by night”

Remember that the four segments analyzed here were not technically processed in the same way. Indeed, the scenes were shot in the form of a road-movie without any premeditated “staging”. The images are “raw”, they reflect a moment of life immortalized by the camera. The analysis of the visual shot will obviously reflect this state. Hence the schemas used are not the same.

Table 4.1 gives us a glimpse of the choices which have been made in the analysis of the visual shots of these segments. The visual objects were notated according to their thematization and not their function. These segments are relatively short. They all denote a pro-filmic scene in which we can identify people, objects, activities, products, a space-place or even a timespace in 50% of cases. All of them were named and commented upon so as to contextualize them for general research, all were technically described using main typologies of visual techniques and all were temporalized.

Table 4.1. Elements of comparison between the schemas used in describing the market scene

The list of the different objects analyzed objects is available at the level of the visual shot of each segment (left part of the screen – see Figure 4.6. One need only select them for the elements which are linked with them (contextualization and technical processes) to become accessible on the right-hand side.

4.2.4. Some specific uses of the analyzed visual shots

In section 4.2.3.1 above, “The visual shot of an interview”, we mentioned a number of potential uses for a visual analysis of an interview.

However, the most interesting uses as regards the exploitation and re-appropriation of the visual contents are, without a doubt, for reports, road-movies and documentaries, which bring a whole sample of “objects” into play to make up a speech or a story to be told. Deciphering these objects and indexing them in a contextualized way will enable them to be used in various thematic or educational folders, for comparison or visual exemplification purposes, for knowledge fields as diverse as human or cultural geography, urban studies, architectural studies, day-to-day cultural anthropology, etc.

As we shall also see in New uses for digital audiovisual corpora,7 analyzing the visual shots of segments will facilitate a quick selection of relevant elements making up valorization or communication folders, in the context of an exhibition or cultural event.

4.3. Analysis of the sound shot

4.3.1. General description of the sound shot and analysis procedures

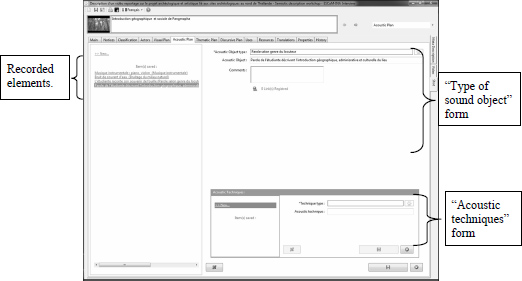

As we have just seen in the description of the visual shot, the Description Workshop offers us the possibility of describing the sound shot of audiovisual texts both at the level of the video and of its segments. The “Sound shot” tab enables the analyst to access to this function.

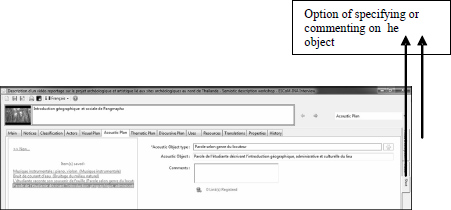

This tab contains three zones (Figure 4.7): recorded elements, two forms to fill in about the type of sound objects that exist in the document, and the acoustic techniques.

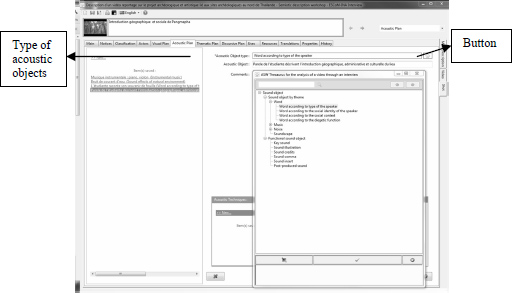

In order to begin to describe the sound shot, the analyst must fill in the first field of the type of sound objects by clicking the button on the right of the field (Figure 4.8). The new window then offers a tree view of the sound shots.

Similarly as with the visual shots, the typology of the sound objects is divided into two main categories: “thematic sound objects” and “functional sound objects”. The thematic sound objects include three main types of objects: Speech (to be identified according to the speaker’s gender, social identity, the social context and its diegetic function), Music (instrumental and vocal), Noise (from normal life, from the natural, social and technical environment) and the Soundscape (the ambient sound). As for the functional sound objects, there are six: the key sound, the sound illustration, the sound credits, the sound comma, the sound insert and finally the post-produced sound.

Figure 4.7. The “sound shot” tab

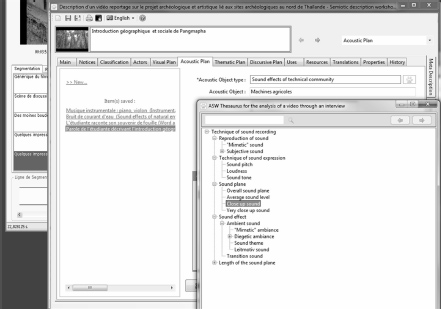

Figure 4.8. The “sound shot” tab and the tree view of the types of acoustic objects (foreground)

In order to index the sound elements, the analyst has to choose one of these objects. He may then specify the exact nature of this element in the two free fields “Acoustic objects” and “Comments” which respectively serve to name and to contextualize the identified object (Figure 4.10). In concrete terms, the acoustic object indexing “Instrumental music” may be followed by the name of an instrument, e.g. “piano”, and a contextualization of it: “solo piano”.

Figure 4.10. Sound shot form

Figure 4.11. The “sound shot” subsection in the description workshop – analysis of the acoustic technique used to stage an object/pro-filmic situation

When the analyst identifies the typology and describes the nature of an acoustic object, he may also index the production techniques associated with this object (Figure 4.11). The techniques of sound staging are divided into four main categories:

– sound reproduction: mimetic sound and subjectivity sound (attenuated sound, cut sound, distorted sound and recovered sound);

– technique of sound expression: sound pitch, loudness and timbre;

– sound shot: overall sound shot, medium sound close-up, sound close-up and extreme sound close-up;

– sound effect: ambient sound (mimetic ambience, diegetic ambience, sound theme and sound leitmotif) and sound transition;

4.3.2. Example of analysis of a video described using the sound shot

We have chosen a documentary in Thai, lasting an hour and three minutes entitled “From (Different) Horizons of Rockshelter”.8 This documentary was produced based on the research notes on the project “archeology of the highlands in Pang Mapha”, Mae Hong Song province (Thailand), (Phase 1–2, 2001–2006). It was cut into 27 segments. Each segment contains different types of sound objects which are very varied and interesting from the point of view of indexing the sound shot).

The objective of our sound analysis is to gain an understanding of how sound expression is used in this documentary film and how it interacts with the visual expression in constructing the narration. We choose to study one single segment in detail.

The first segment of this documentary film, entitled Geographical and social introduction to Pang Mapha, contains three types of sound objects comprising four indexed elements:

– instrumental music (one element: sounds of piano and violin played at the same time);

– noise from the natural environment (one element: running water);

– speech, according to the speaker’s gender (two elements: The student tells us about her memories of the excavations; and in another element the student describes the geographical, administrative and cultural introduction of the place).

We will compare these sound elements to the visual expression elements.

The visual elements indexed in this segment are:

– a field notebook, open (introduced by means of a sweeping camera pan) in which there is a dry bamboo leaf as a page marker;

– the student’s profile (close-up);

– water channel and bamboo forest;

– panoramic view over the Pang Mapha Forest, Mae Hong Son, Thailand;

– sequence showing the social life of the village.

By breaking down these two audiovisual expressions, we observe that two important elements serve as a framework to the narration, to introduce the geographical and social aspect of the dig site. The first is a series of visual shots (a sequence) showing, in this order: a medium shot of a dry bamboo leaf on the field notebook, a close-up of the student’s profile and a general shot of the bamboo forest (Figure 4.12). The second element is the student’s voice (as the main personality in the documentary). She tells us about her memories of the excavations and describes the geographical, cultural and social situation of the place).

Figure 4.12. Series of visual shots aimed at introducing the geographical context of the excavation site (bamboo forest)

A regular synchronization of these visual and acoustic elements is also used to hint at the arrival of the following sequential shot. Thus, forty-nine seconds into the film, the shot showing the water channel is superimposed on the close-up on the student’s face (Figure 4.13). At the same time, the sound of water is added to the sound of the musical instruments, which continue to illustrate this scene.

Figure 4.13. Profile of the student’s face overlaid with the shot showing the water (left) and the sound element, type of noise from the natural environment (sound of the water) indexed with the sound shot of the description workshop (right)

Here, it is obvious that the scenario has been constructed so as to provoke a causal link to an effect which is describable by the viewer. The student opens her notebook where there is a dry bamboo leaf. This leaf represents a memory. It comes from the bamboo forest where the excavation took place. The sound of the water added at this precise moment symbolizes the passage between the memory and the excavation site.

Identifying and deciphering the acoustic objects and their direct relation to the images will enable the analyst to understand the mechanism of the narration and the chosen mise-en-scene. It gives an additional value to the indexed document and creates new entries to the acoustic content of the document, thereby opening up an opportunity for new means of use.

4.3.3. Some uses for sound clips

In the same way as the visual shot, the sound shot enables us to highlight elements (here, sound objects) which could be reused to create various educational or thematic folders. Let us think, for example, of their use to illustrate lessons or seminars, draw a comparison between different modes of acoustic expression, study musical instruments, etc. in domains such as sociology, ethnology, anthropology, or even musicology. Several cases of use of these indexes may be envisaged depending on the typology of the sound objects identified.

4.3.3.1. In an educational or research framework

Let us look again at our previous example – the indexed acoustic elements from the documentary film “From (Different) Horizons of Rockshelter” could be used in many very different ways, such as:

– language learning (contextualization of the Thai language);

– audiovisual production (learning about the effects of synchronization between the sound and visual expressions);

– the hearing and recognition of musical instruments (in musicology or ethnomusicology).

Other examples are possible in a research context. Let us take for example the audiovisual document entitled “Thai cultural performances”,9 filmed at the occasion of the International festival of cultural diversity, UNESCO 2009 and available in the corpus of the Cultures Crossroads Archives10 portal (CCA). Between the thirty-third and seventy-seventh minutes of this document, we can see a long sequence about dance and traditional music, representing four regions of Thailand musically and choreographically. By directly accessing this passage (indexed beforehand as a set of relevant sound shots), we can conceive a new usage scenario and hence suggest to the different research laboratories such as the Research Center for Ethnomusicology (RCE)11 that they study that segment. We can also rework it (by sub-dividing and formatting it) so as to be able to upload it on collaborative study Websites such as the Telemeta platform.12 This platform enables researchers to exchange data online with music-making communities in their native countries. It comprises collaborative tools such as time-codes, spaces for comments, etc.

More generally speaking, the purposeful use of listening to sound extracts in other specific educational situations may also be envisaged. Hence the testimony of a witness may be used for exemplification purposes in history or social anthropology classes. A documentary entitled Parties communes (literally, Common parts),13 available on the CCA portal, offers a series of testimonies from the council-estate residents in Vincennes (near Paris, France) all addressed to Jocelyne and Jean Delval on the occasion of their retirement after 17 years of caretaking. These testimonies constitute a perfect example of what can be achieved in terms of collecting acoustic objects that document a social patrimony.

As for the acoustic extracts of different types of noises (noise from daily life, the social or technical environment), they may be studied in research in social, urban and technical anthropology (see e.g. [BAT 09]).14

4.3.3.2. In the context of artistic creation

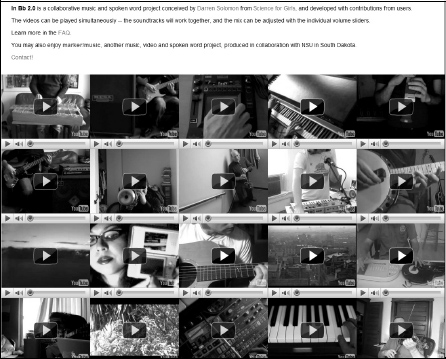

Acoustic extracts may also be used in the context of digital creation. Let us take as an example the page presenting “In Bb 2.0”,15 a collaborative project of music and speech, created by Darren Solomon, composer and producer.

Figure 4.14. View of the collaborative project of music and speech “InBd 2.0”

As Figure 4.14 shows, this Webpage was built using extracts from different audiovisual records from YouTube. The contents of these extracts refer to several types of sound (musical instruments, speech, ambient noises, etc.). Free choice is given to the Web surfer as to how he wishes to view and listen to the different extracts. Either he listens to them one after the other, or plays them randomly, or may even choose to play several of them simultaneously. In this way, he in fact acts as a composer.

1 Chapter written by Elisabeth DE PABLO and Jirasri DESLIS.

1 On this topic, see the scientific report on Task 2, Subtask 2.3 of the ASW-SHS project entitled “Textual and audiovisual description”, available at: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr:8080/site/projets/asa/IMG/pdf/DS1_ST_2.3.pdf.

2 See Chapter 3, an overview of the Description Workshop.

3 On this subject, see e.g. [JOL 94].

4 See Chapter 3 “Description Workshop for audiovisual corpora” for a more detailed description of the Video and Segment sections.

5 Interview with Rina Sherman, “7 years with the Ovahimba”, available online at: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/arc/1873/.

6 Report: “The city of Hong Kong – an audiovisual documentation on everyday life”, available online at: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/arc/1788/.

7 On this subject, see Chapter 2 of New uses for digital audiovisual corpora.

8 http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ADA/1909/home.asp.

9 http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/Arc/FR/_video.asp?id=1969&ress=6320&video=132052&format=88.

10 http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/Arc/FR/Default.asp.

11 http://www.crem-cnrs.fr/presentation/presentation.php.

12 http://archives.crem-cnrs.fr/.

13 http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/Arc/2110/.

14 [BAT 09] BATTESTI V. [Sound atmosphere in Cairo: suggesting an anthropology of the sound environments], at Hal.archives-ouvertes.fr, 24 September 2009, [online]. http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00341934/ See also the author’s personal Website: http://anthropoasis.free.fr/spip.php?article439.