Chapter 1

Context and Issues 1

1.1. The ARA program – a brief historical overview

This book presents the results of a 10-year collective research effort on the issue of analysis of audiovisual corpora forming part, e.g. of a digital library. The advantages and issues involved in analyzing an audiovisual corpus are many and often very different from each other. In any case, they far exceed the “standard” framework of library and/or documentary sciences and techniques. On the other hand, they are reminiscent of the issue of monitoring expertise and concrete exploitation of information or knowledge in the different economic sectors.

For all contributions in this book, the reference context for addressing the question – as complex as it is exciting – of analyzing audiovisual texts or corpora is the ARA (Audiovisual Research Archives – in French: Archives Audiovisuelles de la Recherche1 or AAR) program. The ARA program is a research and development project of the Cognitive Semiotics and New Media Team (Equipe Sémiotique Cognitive et Nouveaux Médias – ESCoM) of the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (FMSH – House of Human Sciences Foundation) put in place in 2001 following several years of research on the conceptual analysis of digital data and the issues surrounding digital libraries for research, education and culture (see [DFS 97; VHF 97a; VHF 97b; AKV 99]). The ARA program is especially dedicated to the issue of compiling, processing and analyzing audiovisual corpora, as well as publishing (and republishing) them online.

In 2000, by means of a French research project entitled OPALES (“Outils pour des Portails Audiovisuels Educatifs et Scientifiques” – literally, Tools for Educational and Scientific Audiovisual Portals)2 and following an initial assessment of the needs of the scientific community regarding the exploitation of audiovisual contents via the Internet [DPL 01], a prototype was specified and developed for an “online video library”-type generic tool aimed at promoting scientific and educational events.3 The classification of the audiovisual collection of this very first video library, the predecessor of the ARA, was made based on an early and rudimentary metalanguage for describing audiovisual content (i.e. based on a domain ontology).

The “Opales” video library prototype, as well as the very first metalanguage for audiovisual content description, then formed the basis for the definition and implementation of a far more ambitious program of digitization and dissemination of scientific and cultural documented heritage in the form of corpora of all sorts of audiovisual texts, i.e. from almost raw recordings with no notable postproduction to documentaries, reports and other “real world” and “direct” shoots, although not (hitherto) including fictional productions. After some hesitation, this ambitious project was called – in French – Programme Archives Audiovisuelles de la Recherche (AAR), translatable as Audiovisual Research Archives Program (ARA).

The implementation and general running of the ARA program and its different activities was preceded by a considerable amount of previous work, aimed at defining as explicit a strategic framework as possible, and a guiding scheme for specifying the identity, the particular place of the aforementioned program in the context of the research on digital libraries and their concrete exploitation. Thus, when defining the general objectives of the ARA program, we focused on the fact that they should definitely not be reduced to a “simple” program of recording events and “online publication” as is the case for the vast majority of video library, photo library and other multimedia library projects which, indeed, often content themselves with a very modest policy regarding the exploitation, valorization and reuse of their documentary collections.

On the other hand, the ARA program was created from the word “Go!” to fulfill the following two joint objectives:

“[…].

1) compilation and distribution of public research heritage in the form of audiovisual, visual, sound and text files (with digital support), of scientific events such as interviews with researchers, seminars, scientific exhibitions, reports, video montages, documentaries, etc.;

2) design and development of technologies and tools suitable for the production and management of audiovisual and text archives, the processing of audiovisual records and their use in the contexts of research, education and scientific journalism.

[…]” [AAR 04, p.3].

The wording of these two objectives unequivocally shows that, in the context of the ARA program, we absolutely preclude the idea of reducing the work of compilation and distribution/exploitation of knowledge heritage to a simple technical process of capture/digitization of audiovisual data, their computerization and online distribution.

On entirely the other hand, this work depends intrinsically upon more complicated procedures, as regards transforming any digital data (a photo, an audiovisual or sound recording, etc.) into a genuine cognitive resource for a specific audience and specific uses. Yet, this transformation may not be done without suitable approaches, methodologies, conceptual resources (such as scenarios and models for compiling, describing, publishing/republishing and preserving audiovisual corpora in the long-term), appropriate computer tools and, of course, skills and therefore specialized human resources. Hence, naturally, the specificity of the ARA program, as compared to other similar initiatives and projects, relies upon the intrinsic links between:

1. the concrete work of constituting, processing, analyzing and publishing audiovisual corpora to document an area of knowledge;

2. The theoretical and methodological knowledge and know-how, the expertise necessary for constituting, processing, analyzing and publishing audiovisual corpora;

3. the concrete achievements - not only in the form of analyzed and published audiovisual corpora but also in the form of so-called metalinguistic (see section: 1.1) and computer resources – for analyzing and publishing audiovisual corpora.

In this book, we will demonstrate through a multitude of examples, how these three aspects, which are essential to a project of constitution/diffusion of a body of knowledge heritage, stand in for and reinforce one another.

1.2. The scientific and cultural heritage of the ARA program

One of the most important aspects in terms of activities carried out as part of the ARA program is, of course, the concrete work of collecting and diffusing knowledge generated in human and social sciences (HSS) by way of particular “events” such as lectures, conferences, workshops, working meetings, research seminars, higher education classes or by structured and in-depth interviews with researchers and lecturer/researchers working in HSS.

In comparison with initiatives close to the ARA program,4 one of the main points of the ARA program has been to accompany and valorize, as far as possible given its budgetary and logistical limitations, the particular position of the FMSH in Paris5 in the French institutional field; a particular position that the historian Maurice Aymard, former administrator of the Foundation, had defined as that of betting not only on the internationalization of research but also, far more “radically”, on the “de-Europeanization and inter-culturalization of the fundamental concepts and issues of [human and] social sciences”.6 Relying, on the one hand, on the FMSH’s geographical and themed programs7 and international networks, and on the other on the fact that the FMSH received (and still receives) hundreds of researchers from all over the world each year, the ARA program was thus able to compile (particularly between 2002 and 2005/2006) a truly exceptional and unique scientific heritage, made up of contributions from researchers in institutions not only in France but in some 85 countries the world over.

This was not only about “hastily” collecting the additions to scientific knowledge by researchers from a many countries in the world. The stated goal of the ARA program was to methodically collect information from colleagues working in France or abroad. These methodical collections relied on explicit models and field scenarios (see section: 1.4) and were quite deliberately implemented when compiling audiovisual analysis corpora on certain chosen themes. Therefore, from 2005/2006 onwards, a number of particularly important aspects for contemporary research were advantaged, among them the following three:

1. the often conflicting relationships between globalization, cultural diversity, multiculturalism and/or communitarianism and intercultural dialog;

2. the huge (social, political, economic, etc.) need for models and scenarios to understand and evaluate the changes of the modern world;

3. the central questions concerning the construction, the very organization of human sciences, the epistemic and theoretical status of its concepts and models, the “paradigmatic” change from disciplinary research towards inter- or rather trans-disciplinary research on specifically identified issues as well as the relationships between HSS, natural and formal sciences and engineering.

In addition, since 2005/2006, the ARA program has been exploring other field to collect, digitize and distribute knowledge heritage. Hence, projects of collection, analysis, publishing and online distribution of audiovisual corpora concerning traditional knowledge and know-how,8 collective memory,9 geopolitical regions,10 traditions and new forms of artistic expression,11 day-to-day culture,12 European emigration to Latin America,13 etc. have been carried out. The ARA program has thus developed, over the course of its existence, an original and methodologically solid14 approach to the compilation and online publishing of audiovisual corpora.

Among the tangible results of this “policy” of producing scientific and cultural heritage using digital audiovisual technology, the ARA includes, among others:

– a collection of almost 6,000 hours of online videos, made up of a series of thematically-delimited corpora such as, for example, the “Social History” corpus (around 600 hours of online videos), the – “Cultural and Linguistic Diversity” corpus (around 450 hours of videos), the “Globalization and Sustainable Development” corpus (around 250 hours of videos), the “History of Mathematics and Geometry” corpus (around 160 hours of videos), the “Religious History and Study” corpus (around 200 hours of videos), etc.;

– an audiovisual collection whose authors form a 2,500-strong community working in over 900 institutions and 85 countries worldwide;

– an audiovisual collection bringing together videos in 15 different languages;

– an audiovisual collection distributed on the ARA Web portal and/or – a series of other thematically- or geographically-delimited Web portals15 forming part of the ARA;

– an audiovisual collection entirely published in the form of “mini-Websites” with each “mini-site” corresponding to a scientific event – a field of research, a cultural exhibition, etc. (hence, up to the end of 2010 the ARA portal contained and distributed about 650 audiovisual mini-sites including nearly 350 structured and in-depth interviews, 70 research seminars, 150 discussions, 50 reports and documentaries and 15 audiovisual “field” documentations);

– a collection of which some parts are re-published in the form of themed folders (in late 2010, around 85 themed folders), bilingual folders (in total, around 80 bilingual folders including French/English; French/Arabic; French/Russian; French/Chinese etc.) and themed video-lexicon (devoted e.g. to world languages, intangible cultural heritage, etc.).

Therefore, in 2009, the ARA program was qualified by the very official Agence d’Evaluation de la Recherche et de l’Enseignement Supérieur (AERES) [Agency for the Evaluation of Research and Higher Education] thus.

“[…] The ARA are a good example of the promotion of the FMSH’s cultural heritage by the systematic use of new digital technologies based on the activity of the Cognitive Semiotic and New Media Lab (ESCoM). […] The ARA are thus the product of this team’s activity. Their objective is the formation, distribution and exploitation of public heritage of knowledge produced by HSS in the form of video recordings, classes, seminars, interviews, etc. to the benefit of research, education, and learning. Over the years since their commissioning [4 years, 2006–2009, P.S.], the ARA have become a major player in this field in France […]” [AER 09, p. 20].16

1.3. The working process

As has already been said, the ARA’s activities cannot be reduced to technical procedures for capture, digitization, processing and distribution of audiovisual data. These only constitute a particular set of activities among others.

The ARA program does however rely on close coordination between several sets of activities which are essential to the implementation and running of a highly complex working process covering all stages from the production of audiovisual data to their publication.

Thus, alongside a first set of rather technical activities, a second set of activities contributes to the central task of transforming digital data into a cognitive resource. This includes, e.g. the following activities:

– definition and preparation of collections of audiovisual data;

– selection of audiovisual corpora (on the basis of collected data) for analysis and publishing;

– montage and postproduction of the selected corpus according to montage scenarios;

– analysis, description and indexing as well as (linguistic but also cognitive or cultural) adaptation-translation of the selected corpus;

– publication and/or republication of the corpus post-produced and analyzed/ adapted according to a publication model and scenario.

A third set of activities concerns activities whose aim is to preserve the originals, the legally valid documents, safeguarding the heritage but also the legal deposition of all the achievements of the ARA program.

A fourth set of activities, transversal to the first three, is concerned with the R&D activities in the true sense. One of the most obvious objectives of R&D activities as part of the ARA program is to reinforce its internal abilities in order to satisfy to its objectives of compiling and publishing/distributing scientific and cultural heritage.

The issue of strengthening the internal capabilities of the ARA program relates as much to the technical working environments as it does to the approaches to and methods for the collection, processing, analysis, publishing, distribution, exploitation and preservation of audiovisual corpora. To that end, what is required is a team and various networks of researchers, engineers but also professionals bringing together multidisciplinary skills (multidisciplinary skills which allow us to cover computing and a wide variety of approaches and disciplines in HSS) who methodically work according to explicit procedures, on issues which consider the existing and/or potential needs of the ARA program. The R&D activities undertaken as part of the ARA program are primarily aimed at defining and developing two specific types of resources:

1. computer resources suitable for effectively carrying out concrete work on an audiovisual corpus;

2. so-called metalinguistic resources necessary either to compile corpora or to analyze and/or process them, or even publish/republish them (in particular these are models and scenarios for production, analysis and publishing of audiovisual corpora; see section 1.4).

There are other activities which complement those we have just identified. Let us above all remember that it is hugely important to identify the main sets of activities for a project of compilation and distribution of knowledge heritage.

It is only on the basis of this identification that we may define the stages and explicit procedures of working process according to which the tasks of producing, analyzing and publishing audiovisual corpora documenting an area of knowledge or expertise are organized and carried out. This process is, indeed, even more complex than is suggested by an extremely simplistic (but unfortunately still very widespread) vision reducing it to a few technical gestures concerning “putting a video online” which seems to essentially consist of simply uploading the file containing the video, accompanied by a basic computer record.

We were therefore led to define the said process as precisely as possible, for scientific and technical as well as practical and financial reasons:

– scientific and technical reasons: the better to be able to identify the gaps, limits and obstacles to be overcome during the process of production/publishing so as to make it more efficient and more easily adaptable to the expectations of the audiences and stakeholders concerned as well as to the specificities of the corpora themselves;

– practical and financial reasons: the better to be able to define the competences and profiles sought, achieve better management and monitoring of the process itself and finally, also, to better calculate the costs incurred in production, processing and analysis as well as publishing and preservation of an audiovisual corpus.

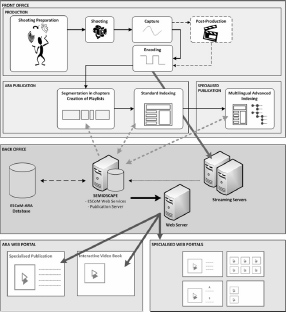

In view of the experience gained during years of work compiling audiovisual corpora documenting HSS areas (especially between 2001/2002 and 2005/2006), we were able to define and implement, from 2004 onwards, the working process which characterizes the ARA’s activities as far as the compilation, publication and distribution of knowledge heritage are concerned. Figure 1.1 gives an overview of the 5 major stages according to which the said process is organized.

Figure 1.1. The five major stages making up the process of production, processing, analysis and publication of an audiovisual corpus

Figure 1.2 shows a table which, for each stage, details the main activities to be carried out. Besides the fact that this table explicitly shows all the complexity of a project or program of compilation and distribution/conservation of knowledge heritage, it is extremely useful as a reference framework which, on the one hand, enables us to implement genuine management of a team which is necessarily multidisciplinary, and on the other hand to calculate the relative durations of the different activities in view of potential specificities linked to the domain, the corpus to be compiled or its use. We refer the interested reader to Chapters 4 and 5 of the book Digital Audiovisual Archives,17 which describe two concrete examples of the creation of audiovisual archives: the first example is dedicated to the compilation of an audiovisual archive on the intangible cultural heritage of the so-called indigenous communities which live in the Andean regions of Bolivia and Peru; the second to one on a country – Azerbaijan. These examples demonstrate very well all the complexity of the working process including the production, processing and analysis as well as the publication of an audiovisual corpus documenting a given patrimony.

Figure 1.2. The major activities defining the stages of the working process for the constitution/publishing of a heritage of knowledge18

Using the table identifying the different activities which are part of the working process for constituting/publishing knowledge heritage (Figure 1.2), it becomes far easier to predict (with a certain degree of accuracy) the approximate date a corpus will be published, the duration of the work to be undertaken for it to be published, the human resources (i.e. skills) to be mobilized and finally the cost incurred by an operation to compile and publish/distribute knowledge heritage.19

The table (Figure 1.2) representing the different activities of the process of producing, processing/analyzing and publishing an audiovisual corpus encourages us to carefully distinguish between a “video-library”-type project and a project aimed at compiling and distributing an audiovisual piece cultural and scientific heritage. In the first case, we imitate more-or-less accurately a model which in itself is rather conventional (i.e. the unilateral distribution of content model, the paradigmatic example of which is television) of capture/distribution of scientific, cultural or other events. In the latter case, the capture and distribution of a scientific event is only a small part of the work. All its richness but also all its complexity relies on the fact that it has to “solve”, or rather find satisfactory solutions to, the following issues:

– the “correct” constitution of a corpus, i.e. the constitution of a relevant corpus;

– the “correct” analysis of the corpus, i.e. a relevant analysis and;

– the “correct” publication, a relevant publication of a corpus.

These issues lead us directly to the importance of knowledge engineering and semiotics for the ARA program.

1.4. Knowledge engineering in the service of the ARA program

1.4.1. Some questions

During the first period of collection of research testimonies in HSS (i.e. 2002–2005), there gradually appeared a whole series of interrogations and issues which, indeed, constitute the background and the main motivation of a new wave of R&D activities since late 2006. Three of these are:

1. the quality and richness of the content of the collections forming part of the ARA are somewhat overshadowed by the quantity (volume) of hours offered to the interested community (at the end of 2006, the ARA’s collections comprised around 3,500 hours of digital videos; at the end of 2009, around 5,800 hours);

2. the content conveyed by an audiovisual text (a raw recording, a montage, a corpus, etc.) has its own identity;

3. the audiovisual content is almost completely monolingual (i.e. the vast majority of recordings were carried out in a single language).

The first problem is reminiscent of the issue of description, classification and indexing of audiovisual corpora. The second problem relates rather to the explanation of the content of an audiovisual text, taking account both of its specific identity and the cultural and cognitive “profile” of the target audience. The third problem is traditionally associated with the translation of an (audiovisual) text, i.e. linguistic comprehension of the content and metadata explicating the content. These three problems constitute genuine issues, as much for better distribution of cultural or scientific heritage on a digital “market” which is intrinsically multilingual and multicultural, as for an appropriation which is better-adapted to the expectations and needs of the user communities in question?

In addition, the regular statistical analyses of visits to the ARA Website, the surveys put to the ARA audience via an online questionnaire on the Web portal20 and finally regular feedback from users (teachers, researchers, students, etc.) of the ARA’s audiovisual collection, demonstrate the obvious limits of a “simple” multimedia library, contenting itself with a set of more-or-less “standard” accesses to its collections: varying degrees of difficulty in locating and selecting a relevant piece of information from large audiovisual databases; temporal linearity of the audiovisual flux preventing more flexible forms of exploration, such “leafing”; absence of contextual help for the exploration and appropriation of collections of audiovisual resources; absence of usual terminologies which could help to better understand the structure of a collection and consequently explore it better; too many difficulties (technical but intellectual as well) in using or reusing audiovisual resources for specific activities in research but also in education, scientific vulgarization, etc.

1.4.2. Recourse to the semiotics of the audiovisual text

These and many other problems, have brought back to the forefront of debate one of ESCoM’s main objectives in participation in the aforementioned OPALES project; i.e. to define and develop a metalanguage for describing audiovisual texts based – in particular – on a semiotic approach to the text (see [STO 99; STO 03a; EHE 07; FRS 09; GRO 11]).

Without wishing to go into too much theoretical detail here (for more information, see [STO 03a] and [STO 12]), the semiotic structure of the audiovisual text (and of any other type of texts) may be “approached” in an intuitive and simple manner using the following seven standard questions:

1. What are the passages, moments, in the linear flux constituting the discernible (perceptible) part of the audiovisual text which catch/may catch the attention (i.e. what are the “information-carrying” segments for a given audience)?

2. What are these “information-carrying” segments about (i.e. what are the subjects addressed by the segments, what are the selected topics and themes)?

3. How are the subjects tackled and addressed in these segments (i.e. what is the – enunciative, discursive – specificity of the topics and themes selected in the “information-carrying” segments)?

4. How are the selected subjects progressively developed (described, explained, “narrated”) within a segment and also through the different segments of the audiovisual text where they appear (i.e. what is the narrative specificity of the topics or themes selected within an “information-carrying” segment or set of segments)?

5. What is the expression, the audiovisual “staging” of a topic developed in the segments within which they are selected (i.e. what is the multimodal specificity of the topics or themes selected in the “information-carrying” segments)?

6. What are the similarities/differences in procedures of selection, processing, development and audiovisual expression of a subject between several audiovisual texts forming part of a corpus, a collection or, more generally, a historically-, socially- and/or culturally-delimited field of production of audiovisual texts (i.e. what is the intertextual specificity of a topic or a theme)?

7. What are the similarities/differences between the way that a selected subject is tackled, developed and staged and the expectations, needs/desires and skills of an audience (i.e. what is the pragmatic – historical, cultural, social – specificity of a topic or theme)?

These seven questions help to “fix” and orient ideas and habits well before the production of information (i.e. prior to any filming) as well as afterward (i.e. during the publication proper stages of a resource: description, indexing, etc.).

1.4.3. Metalanguage of description, models and scenarios

In reference to the issues in the seven questions formulated above, R&D activities in the context of the ARA program are concentrated around the following four axes:

1. Implementation of models and scenarios for the analysis, description (indexing, classification, etc.) of audiovisual corpora;

2. Implementation of models and scenarios for the publication/republication of audiovisual corpora so as to better adapt them to the expectations (knowledge, skills, etc.) of their potential users;

3. Also implementation of models and scenarios for the collection of audiovisual data documenting a “field” of investigation (i.e. a field dedicated to the production/publishing of audiovisual corpora used for documenting an area of knowledge/expertise);

4. Development of a working environment enabling the semiotic contribution to be used during the processing of audiovisual corpora in view of their online publication or republication (see section 1.5 and Chapter 7).

Let us take a closer look at the metalinguistic resources of the ARA program in the form of models and scenarios – the working environment will be presented later in this chapter (see section 1.5) as well as in Chapter 7 in this book.

The models are metalinguistic resources which define the structure and organization of audiovisual objects and the scenarios are metalinguistic resources which frame and guide the activities leading to the creation of these same objects. Discussing models and scenarios in terms of “metalinguistic resources”, means that they belong to a metalanguage of description (i.e. the one mainly developed in the context of the ASW-HSS project [Audiovisual Semiotic Workshop-Social and Human Sciences] in order to work in a well-reasoned and explicit manner with and around audiovisual corpora), and that they therefore constitute tools, procedures and therefore self-sufficient cognitive instruments, for any actor involved in this type of work.21 In the context of the ARA program, they are used to collect, process, analyze and publish audiovisual data. Hence, we speak of:

1. models/scenarios of collection (of production);

2. models/scenarios of postproduction (of filming, etc.);

3. models/scenarios of analysis (of description, of interpretation, of translation-adaptation, etc.) and;

4. models/scenarios of publishing/republishing of audiovisual data.

The third category, models and scenarios of analysis, forms the main subject of this book. We will present a string of examples of these and show how to use them concretely via a specialized working environment. In [STO 12] there are more detailed explanations relating to the ASW metalanguage of description (including the models and scenarios of analysis). Let us take a brief look at the other classes of models and scenarios identified below:

1. models and scenarios of collection and production which serve either for the constitution of a new audiovisual collection documenting an area of expertise, or for the “reasoned” enrichment of an existing audiovisual collection.

2. models and scenarios of publication which also serve for republication (i.e. reuse of an already-published video in another context by adapting it to the specificities of the new context of publication) as well as the new forms of collective publishing, spread out in time and space (i.e. publication of audiovisual resources by a collective actor – a group, an institution – which may be located anywhere in the world and may also act as an author over time).

1.4.4. Models and scenarios of collection/production of audiovisual corpora

The models and scenarios of collection (production) first and foremost guide the preparation and creating of a shoot or of a series of shoots. Collection (or production) is a very complex task which is composed of a whole series of activities (see section 1.3). The collection may closely follow various strategies: more or less intuitive, more or less well circumscribed, more or less restrictive in terms of the documentation needed, subject or not to explicit procedures and norms (of quality, etc.).

At any rate, this is a deliberately oriented activity, which attempts (with more or less success) to solve the issue of obtaining the primary material (i.e. audiovisual data) which is necessary in order to create the cognitive resources for a given audience. In that sense, the aforementioned activity of constitution of heritage is either compulsorily preceded by the activity of description/modeling of the area to be documented and of the characteristics to which the documentation must conform, either framed by a sort of guide, or even simply by a “mind map” based on which it is carried out.

In other words, any constitution of a “field corpus” is carried out in reference to an intellectual framework. The implementation of an intellectual framework is part of the activity of definition, development and monitoring of models and scenarios of collection (of production) of audiovisual data which contribute to:

1. the definition and conceptual specification of the object (domain) of a patrimony to be digitized;

2. the definition and preparation of the type of field (type of investigation, geographical and temporal framework, social context, stakeholders, sources of information, etc.), and the collection of data documenting the heritage;

3. the reasoned and controlled conduct of the act of filming (i.e. of audiovisual but also photographical, cartographic, verbal, etc. recording);

4. the computerization of audiovisual data based on a field in a database or a digital archive;

5. the location (identification) of relevant rushes from the digital archive to constitute the corpus which will serve as input for the activities of postproduction on the one hand and analysis on the other;

6. “new” forms and dynamics of constitution of audiovisual collections documenting “fields”: “remote” (spatially and/or temporally) constitution of such collections, “nomadic” constitution or even concerted and negotiated constitution of collections by a community of actors and;

7. finally, the long term preservation of the cultural heritage in the form of audiovisual collections which themselves are constantly evolving.

On the ARA Web portal22 as well as on the ASW-HSS project Web portal,23 one can find a wealth of documentation which presents models and scenarios for the preparation of fields of collection of audiovisual data. A particular effort has been made for the preparation and the monitoring of interviews with researchers. Hence, each interview has been prepared with the people concerned (notably with the researcher him/herself) and carried out following a plan, a scenario with the aim of collecting relevant information relating to “problem places” (generic soundbites) defined beforehand in the interview guide. For each interview, a script has been written (either during or after the interview). The script is a kind of form according to which we collect information, references and other data then used for recording the data collected as well as constituting a working corpus for the postproduction and the analysis.

1.4.5. Models and scenarios for publishing/republishing

Let us again briefly consider the class of the models and scenarios of publication. In the context of the ARA program, the publication/distribution of an audiovisual corpus which has been analyzed beforehand and/or post-produced is necessarily carried out according to a publication model.

The definition of the standard publication model relies on the notion of an event [STO 03c]. A (scientific) event such as an interview, seminar, conference or even inquiry, excavation, concert, etc. is documented by a set of audiovisual and other resources including the collected, processed and analyzed material. The advantage of conceiving a publication thus is twofold:

1. the videos which are published online are immediately contextualized (with regard to the event they document) while of course leaving the possibility open to reuse them in other contexts;

2. online publishing is not a process necessarily linked to an author, or rather, to an authorial instance, but it may be the result of a collective process distributed over time and space.

More particularly, the publication of the audiovisual resource itself– on an event’s Website – in the form of an “online video” (i.e. a video documenting such-and-such a part of an interview, such-and-such a lecture during a conference, etc.) has firstly been defined in a metaphorical reference to books like a sort of interactive video-book, i.e. a document made up of chapters (sequences) made available to the interested audience either in the form of free reading or in the form of guided reading.

In 2006/2007 we started to develop and partially realize new publication models – models such as the themed portal,24 the video-lexicon25 about a topic or a theme, the narrative path among a set of sequences which are thematically similar, the themed folder,26 the bi/multilingual folder,27 the educational folder,28 etc. The diversification of the kinds of publication of course pursues the goal of better exploiting the intrinsic richness of the audiovisual collection of a video library such as that of the ARA. We will present some uses in Chapter 10 of this book.

1.5. The digital environment and the working process

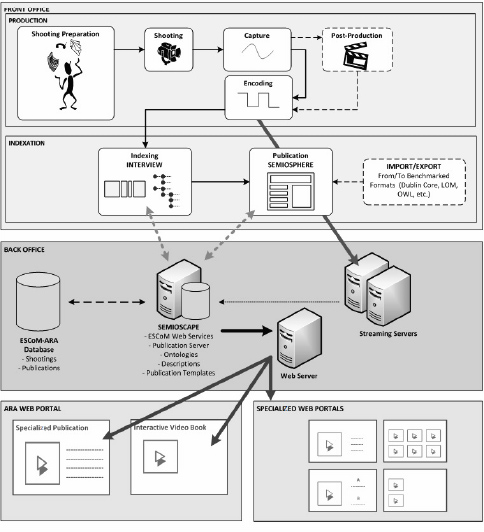

The working process (see section 1.3) – i.e. the different activities, tasks and stages necessary to constitute, process, analyze and publish/broadcast knowledge heritage – takes place within a digital working environment possessing appropriate technologies and tools for the collection (filming, sound recording, etc.), processing (digitization, montage, compression and transcoding, etc.) and finally analysis, description/indexing and publication of audiovisual data. As shown in Figure 1.3, the environment defines and “orchestrates” three more specific processes:

1. The process of audiovisual production. This process brings together all the tasks, from the definition and planning of afield (of digitization) to the distribution of digital videos, including the filming proper, the technical acquisition of the collected rushes in the form of computer usable files, cleanup of the files and even their transcoding in such-and-such a distribution format.

2. The processing and basic publication of a filmed field (i.e. of a scientific event, a cultural demonstration, an inquiry, etc.). The video files forming a given audiovisual corpus are analyzed, cut, edited, indexed and enriched according to a set of guidelines explicitly defined in view of their publication in the form of an “event Website” on the ARA portal.

3. Finally, the processing (analyses, descriptions, indexing, annotations, etc.) and specialized (re-)publication suitable for specific uses. This process may be carried out based on pre-existing audiovisual publications which are distributed on the ARA portal.

Figure 1.3. The general digital working environment of ESCoM’s ARA program

Figure 1.3 is a diagrammatic representation of ESCoM working environment. The front office represents the working process that the users follow, divided into successive tasks that are done using specific tools. The back office represents the technological environment of ESCoM’s ARA program. Finally, the third band of Figure 1.3 shows the publications produced by the back office based on the work carried out in front office by the users.

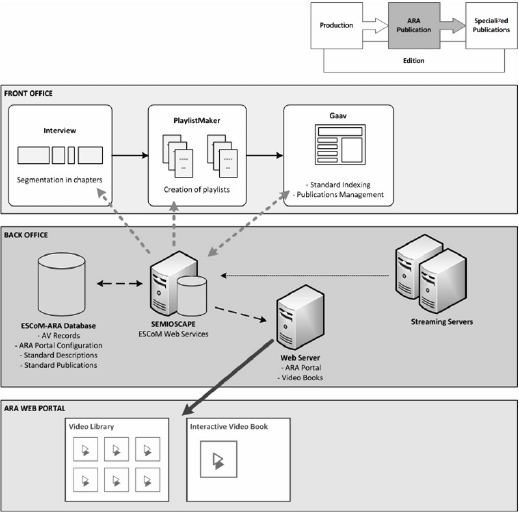

Figure 1.4. The “basic” publishing environment ofESCoM’s ARA program

The second process identified in Figure 1.4, processing and “basic” publication represents the standard process for the publishing of a video on the ARA portal. Audiovisual recordings of a field lato sensu (also including recordings of a seminar, an interview, a conference, etc.) are published on an “event” site (see section 1.4) and in the form of an “interactive video book” which constitutes the ARA’s standard publication model. This process takes place in 3 stages:

1. Segmentation of each audiovisual document into sequences using a tool called Interview (first developed by the Research Department of the French National Audiovisual Institute and then adapted to the particular needs of the ARA program by ESCoM). After viewing the video several times, the analyst identifies the chapters, virtually cuts the audiovisual text and names each part in Interview (as we shall see later on, Interview is also, for now, the software for segmentation in the new ASA studio).

2. Creation of playlists, using the PlaylistMaker tool developed by ESCoM. Indeed, the segmentation done in Interview cannot be interpreted by a multimedia player. PlaylistMaker enables us to convert that segmentation into playlists in ASX format, for each video format.

3. Indexing and publication, using an old application named GAAV (“Gestion des Archives Audiovisuelles” – translated as AVAM - Audiovisual Archives Manager) also developed by ESCoM and facilitating integral management of both the audiovisual publications on a Web portal, and the Web portal itself and its audiovisual collection. AVAM is soon to be replaced by the Publishing Workshop in ASA Studio. However, for now, this task is performed as follows:

– The work carried out in PlaylistMaker is imported into AVAM. All the information relating to the audiovisual texts segmented using Interview is recorded (chapters, filepaths for the videos, headings) in AVAM.

– The publishing manager uses AVAM to edit the information relating to the event the audiovisual documents are about (by details of identity, presentation, speakers, themes, additional pages, further resources, etc.).

– The Website dedicated to the event is published directly on the ARA portal and/or on one of the portals generated using the AVAM application. Furthermore, the videolibrary of the Website portal (new releases, access by theme, collection, speaker, language, etc.) automatically updates itself.

From a technical point of view, a set of Web services (or applications), developed by ESCoM entitled Semioscape (see Figure 1.4), links the software with the servers making up the technological environment of the ARA program, and performs all the necessary processing.

The process of handling and of “basic” publishing process is now totally standardized and orchestrated. It yields standard publications not only on the ARA Web portal but also on all the web portals generated and managed by the AVAM application, as is the case, e.g. of the AmSud29 portal hosting an audiovisual collection dedicated to Latin America.

In addition, it forms a solid basis for considering and progressively orchestrating the processes of handling (analyses, adaptations, etc.) and specialized publication used to explore and implement new strategies of exploitation, use and valorization of audiovisual corpora. Two distinct cases must be taken into consideration here:

1. The case of publication of previously-analyzed and/or (linguistically, culturally, etc.) adapted audiovisual corpora in the form of specialized Web portals (specialized by theme, geographical region, historical period, institution, etc.).30

2. The case of publication/republication by genre as well as by specialized “accesses”. As we have already seen (section 1.4), an audiovisual text is distributed either as documenting an event (case of the standard publishing model), or as part of a folder dedicated to a specific topic, as part of an educational folder for such-and-such a course, or even in a form more-or-less closely adapted to a specific audience and their expectations and skills (either linguistic or cultural).

However, working with an audiovisual corpus in this way presupposes on the one hand the implementation of a set of models – i.e. metalinguistic resources (a metalanguage) guiding the work of analysis and publication, and on the other hand, the enrichment of the existing technological environment by way of new applications, services and tools.

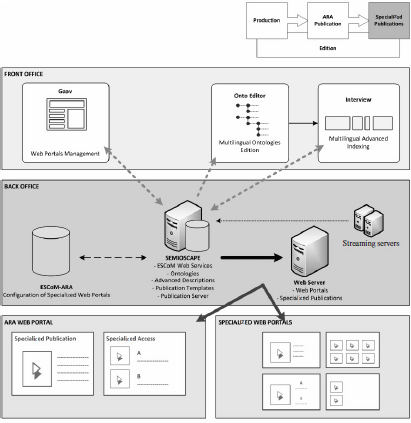

Since 2006/2007, thanks to R&D projects preceding the current ASW-HSS project, the following have been developed and integrated into the existing technological environment, as Figure 1.5 shows:

1. the OntoEditor tool, which serves to create the metalinguistic models (see section 1.4) needed in order to analyze audiovisual corpora;

2. several versions of a domain ontology recorded in the form of XML files and tested on concrete fields of application and which constituted the input when developing the ASW domain ontology;

3. a new working interface for the description and indexing of videos using set forms which served as input to the development of the ASW Studio;

4. a simple interface for publication of the analyses of a video in the form of themed or bilingual folders.

Hence, at the beginning of the ASW-HSS project, the ARA program was endowed with an environment allowing it to carry out already relatively sophisticated analyses and diversified publications. However, this environment does have its limits:

– The basic and “specialized” publications, carried out in the working environment of the ARA program do not communicate with one another. While they are broadcast together on the ARA portal (and all other portals belonging to the ARA program), they cannot be managed together.

– The ontologies only represent hierarchical lists of conceptual terms; the relations between the terms, beyond the taxonomy (this term is more general than that term, etc.) have not been taken into consideration. Hence, analyses of the audiovisual corpora could not be done with dynamic models of description based on configurations of conceptual terms (see Chapter 5).

The actual publication of analyzed audiovisual texts is too rigid, too strictly limited to four basic publication models, and two specialized publication models.

Figure 1.5. The environment of specialized publications of the ARA program of ESCoM

The “ideal” environment – as defined in 2009 – is shown in Figure 1.5, with the following three desired aspects, which are for the most part provided for in the ASW-HSS project:

1. Adopting a single format for description and indexing, whatever the type of publication. To that end, a partially renewed working environment has been developed in the form of two specialized workshops making up the ASW Studio – the ASW Segmentation Workshop for audiovisual texts and the ASW Description Workshop for audiovisual texts. The descriptions are always stored on Semioscape in XML format.

2. Developing a – light and open – publication format, not considering any information on indexing (apart from information on the source of the description). The publication formats will be useful to authors for uploading audiovisual corpora which have been described and indexed in advance according to their preferences. This work is carried out using the ASW Publication Workshop, which relies on an application developed by ESCoM called Semiosphere.

3. Developing, within Semioscape, a scalable platform able to convert all descriptions carried out as part of the ARA program into standards (RSS, Dublin Core, LOM, OWL, MPEG 7, etc.). The aim here is not only to be able to export information to external platforms, but also to be able to publish indexed videos using other tools, particularly those developed by ESCoM’s partners in the ARA program.

1.6. Analyzing an audiovisual corpus using ASW Studio

We have just seen that throughout the ARA program’s existence, the description or, as we prefer to say, analysis of an audiovisual text has grown in importance in any audiovisual production/publication project either to document an event or an area of knowledge/expertise, or to create patrimony from it. This activity is acquiring a particularly central position in the context of projects of “specialized” publication/republication of audiovisual corpora in the form of themed sites, new access to an audiovisual collection hosted by a portal or even in the form of specific genres/types of publication such as folders dedicated to a particular topic, educational folders, “Web documentaries”, etc.

Two central points must be emphasized here. Firstly, for the user to view or consult an online video, a whole set of activities must take place beforehand in order to arrive at such a result (see our explanations in the previous parts of this chapter). Secondly, an audiovisual text which is published on a Website is not yet necessarily in itself (a priori) a cognitive resource for an audience, i.e. a good that the audience needs (or seems to need) in order to satisfy a lack of knowledge or, more usually, curiosity. It becomes so only after it has undergone a qualitative transformation which changes its status from a “simple” textual object possessing its own cultural and cognitive specificity to a “good”, adapted to an audience, its culture and its expectations.

This qualitative transformation of an audiovisual text into a knowledge resource sui generis may take very different forms. It may be a not-particularly formal act based on the audience’s experience or habits (such as finding the interesting audiovisual moments, reading/viewing these moments, subsequent reflection and discussion, etc.). It may also take a professional and/or institutionalized form, e.g. in the context of the implementation, monitoring and exploitation of knowledge heritage (scientific or cultural, collective or personal, professional or amateur, etc.).

In this book, we will thus investigate a specific category of tasks which contribute to transforming any audiovisual text into a cognitive resource per se for this or that audience, this or that use. This is the type of task which we designate by the generic term analysis (see Figure 1.7) which encompasses:

1. the task of cognitive modeling of analysis models and scenarios (see [STO 12b]);

2. the task of identification and segmentation of an audiovisual text (see Chapter 2);

3. the task of production of a metadescription explaining the content and objective of a particular analysis (see Chapter 3);

4. the task of paratextual analysis of the audiovisual document in its entirety or such-and-such a segment identified within the audiovisual document being analyzed (see Chapter 3);

5. the task of audiovisual analysis which deals with analyzing visual and/or sound shots at the expense of a systematic analysis of the content created and carried by the audiovisual document being analyzed (see Chapter 4);

6. the task of thematic analysis which, on the other hand, prioritizes eliciting, describing and interpreting the audiovisual content (see Chapter 5);

7. Finally, the task of pragmatic analysis, which deals with the elicitation and adaption of the profile (of the “identity”) of the document being analyzed, to such-and-such audience, such-and-such a use (see Chapter 6).

Figure 1.7. Type of analysis of an audiovisual corpus

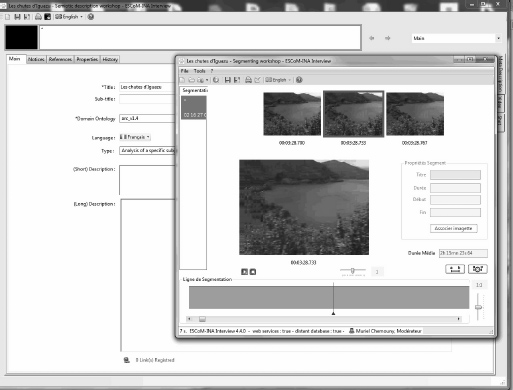

Figure 1.8. The Segmentation (foreground) and Description (background) Workshops in ASW Studio

With the exception of the task of cognitive modeling of the models and scenarios of analysis dealt with in [STO 12b], all the other tasks listed above will be presented and exemplified in Chapters 2–6 of this book.

The execution of all these tasks is made possible by ASW Studio environment, which is made up of four main workshops: the Segmentation Workshop for audiovisual texts; the Description Workshop for audiovisual texts; the Publication Workshop for a text or corpus of audiovisual texts; and finally the Modeling Workshop for metalinguistic resources to carry out the segmentation, description and publication.

Figure 1.8 shows a combined view of the Segmentation and Description Workshops. The Segmentation Workshop (Figure 1.8, foreground) is used to break an audiovisual text up into n segments or to identify the passages within an audiovisual text which are relevant to a given analysis. The Description Workshop (Figure 1.8, background) is used to analyze either the entirety of the audiovisual text or such-and-such a part thereof. It is also used to define and present the type of analysis envisaged.

1 Chapter written by Peter STOCKINGER, Elisabeth DE PABLO and Francis LEMAITRE.

1 See http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/EN.

2 The OPALES Project (2000–2002) financed as part of the French PRIAMM program with the National Audiovisual Institute (in French: Institut National Audiovisuel) as a co-ordinating partner, as well as France 2, La Cinquième (which are French television channels), La Cité des Sciences, the CNDP (Educational National Information Center), the LIRMM (Laboratory of Informatics, Robotics and Microelectronics of Montpellier) of the CNRS (French National Center for Scientific Research) and the University of Montpellier and RENATER (French National Technology, Research and Education Network). Complete description available (in French only) at: http://www.semionet.fr/FR/recherche/projets_recherche/00_02_opales/opales.htm.

3 We recall, with a certain degree of nostalgia, that the very first scientific event recorded and published as part of this video library was the International Conference on Geometry in the 20th Century, which was organized by Dominique Flament and his team in history of mathematics and, more particularly, geometry at the FMSH in Paris. The lectures given during this conference are still available at: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/geometrie2000/.

4 In 2001/2002 in France, these were, in particular, Canal U, the higher education video library (http://www.canal-u.tv, only available in French) and the program La Diffusion des Savoirs (The Diffusion of Knowledge) of the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris.

5 See http://www.msh-paris.fr/.

6 On this subject, see the interview conducted by Peter Stockinger with Maurice Aymard for the ARA program in September 2002 dealing with the specificity of the (FMSH) and its missions: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/35/.

7 Let us cite, among its many geographical and themed programs, those with which the ARA program has maintained close relations over the years: the F2DS program in History of Mathematics (Dominique Flament, also head of the Espace Charles Morazé: http://www.centre-charles-moraze.msh-paris.fr/), the ALIBI “China” and “workshop” programs dedicated to exchanges between Chinese- and French-language literature (Annie Curien), the Civilisation du pain [Civilization of bread] program (Mouette Barboff), the Programme International d’Etudes Avancées (PIEA) [International Program of Advanced Studies] headed by Jean-Luc Racine, the Entre Sciences [Inter-Science] program (Angela Procoli, succeeded by François Rochet), the Tic-Migrations program (Dana Diminescu), the Programme Amérique latine [Latin-America Program] (Dominique Fournier), the Programme de coopération Maghreb-France [Maghreb-France Cooperation Program] (Maurice Aymard), the Programme Proche et Moyen-Orient [Near- and Middle-East Program] (H. Dawod), the Programme Inde et Asie du Sud [India and South Asia Program] (France Bhattacharya replaced by Max-Jean Zins), the Programme Japon [Japan Program] (Jane Cobbi), the Programme Russie et CEI [the Russia and CIS Program] (Anne Le Huérou), the association “France Union Inde” [France India Union] (Maurice Aymard), Editions MSH (MSH Publishing) as well as the Programme directeurs d’études associés [Associated Research Directors Program] and the different Programmes de bourses de recherche et postdoctorales [Research and Postdoctoral Bursary Programs]; for more information, see the FMSH Website: http://www.msh-paris.fr/ and the corresponding event on the ARA Web portal: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/.

8 See e.g. the online documentation on artisan bread-making in Portugal, produced in 2008 in cooperation with the ethnologist Mouette Barboff: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1895/.

9 See e.g. the audiovisual documentation entitled “Ils arrivent demain … Ongles, village d’accueil des familles d’anciens harkis” (created in 2009): http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1894/.

10 See e.g. the themed portal “AmSud. Mediateca latinoamericana” put in place in 2007 and dedicated entirely to the history, geography, civilization, society and countries of Latin America: http://www.amsud.fr/ES/.

11 See e.g. the audiovisual documentation entitled “Du griot au slameur. Oralités anciennes, oralités urbaines” produced in 2009 in cooperation with the Département Musiques orales et improvisées de la Fondation Royaumont: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1674/.

12 See e.g. the documentation on daily life in Hong Kong produced in 2007 as part of the “China” program of the FMSH in Paris and led by Annie Curien from the CNRS http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1108/.

13 See e.g. the audiovisual documentation dedicated to French emigration in the 19th Century to the State of Veracruz in Mexico (produced 2005–2007 in cooperation with Javier Perez Siller from the BUAP - the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1631/.

14 For more information see the online documentation on the ARA Web portal: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/FR/about4.asp.

15 Here let us cite the following portals: AmSud – mediateca latinoamericana, a portal in Spanish dedicated to the history, culture, society and peoples of Latin America: (http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/amsud/FR/); Azéri Buta, dedicated to Azerbaijani culture: (http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/azeributa/FR/); Averroès – the France-Maghreb media library: (http://www.france-maghreb.fr/FR/); Diversité Linguistique et Culturelle (Linguistic and Cultural Diversity): (http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/dlc/FR/); Mondialisation et Développement Durable (Globalization and Sustainable Development): (http://www.evolutiondurable.fr/FR/); Peuple et Cultures du Monde (People and Cultures of the World): (http://www.culturalheritage.fr/FR/) and Semiotica, Cultura e Comunicazione (Italian for “Semiotics, Culture and Communication”, jointly developed with the Faculty of Communication at the University of Rome – Sapienza: (http://www.archiviosemiotica.eu/IT/).

16 See FMSH evaluative report, online on the AERES Website: http://www.aeres-evaluation.fr/content/download/13289/186002/file/AERES-S1-Fondation_MSH.pdf.

17 Digital Audiovisual Archives, ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

18 DC is an acronym for Dublin Core, one of the most widely-used metadata schemes (made up of 15 main elements) for describing digital data; see http://dublincore.org/.

19 Note that in the context of the KNOSOS European project, financed 2003–2005 by the Leonardo da Vinci program, ESCoM created a series of online courses documenting the different stages of the working process as part of the ARA program. Here is the URL of the Website diffusing the lessons in question: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/knosos/.

20 See http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/FR/questionnaire.asp.

21 The elaboration of these models and scenarios is a subtle and complex process which, as has already been said, makes use of highly specialized skills in conceptual analysis of areas of knowledge or expertise to be covered by a program of digitization and diffusion of heritage as well as in audiovisual semiotics as being one of the very rare approaches which systematically deals with audiovisual texts, their structure and organization. It should also be noted that the conceptual analysis and modeling of an area of knowledge/expertise are not synonymous with choosing between this-or-that scheme of metadata, and/or this-or-that standard.

22 See http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/FR/about4.asp.

23 See http://www.asa-shs.fr/– “Online documentation”.

24 See e.g. the following themed portals: Diversité Linguistique et Culturelle (DLC) [Linguistic and Cultural Diversity]: http://www.languescultures.fr/, and Peuples et Cultures du Monde (PCM): http://www.culturalheritage.fr/ [People and Culture of the World] developed between 2007 and 2009 as part of two research and development projects entitled LOGOS (this project was financed in the context of the 6th FP or Framework Program) and SAPHIR (this project was financed by the French National Research Agency).

25 See e.g. the video-glossary “Languages of the world” on the Linguistic and Cultural Diversity: http://www.languescultures.fr/FR/_Encyclo_Langue.html, or even the video-glossary “People of the world” on the People and cultures of the world portal: http://www.culturalheritage.fr/FR/_Encyclo_Peuples.html.

26 See e.g. the themed file on the anthropology of illness and myth in Laos and in South-East Asia, created by Muriel Chemouny from an interview with the French anthropologist Richard Pottier: http://www.culturalheritage.fr/1154_fr/.

27 Bilingual folders: French to English (and English to French); Spanish to French (and French to Spanish); French to Italian (and Italian to French); French to Chinese; French to Arabic; French to Russian; French to Turkish.

28 See e.g. the reading portfolio for informal learning, dedicated to the mytho-ecological discourse in the Japanese anime Princess Mononoke (director: Hayao Myazaki) – portfolio which was conceived and created by Muriel Chemouny from a lecture on this topic given by the ethnologist Chiwaki Shinoda, lecturer at the University of Hiroshima: http://www.culturalheritage.fr/1136shinoda_peda_informel_fr/.

29 See http://www.amsud.fr/ES/.

30 As has already been pointed out, as part of the ARA program, since 2006 a whole series of specialized portals has been created, which today serve as models to make the generation and monitoring of such sites easier and, at the same time, customizable; see ARA homepage: http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr.