Chapter 6

Uses of an Audiovisual Resource 1

6.1. The “Uses” part of the ASW description workshop

By the term “use”, we mean the utilization by the end-users of the video being analyzed. A given type of use supposes that the target audience can be defined as an individual or a group, sharing a more or less stable body of common knowledge.1 Hence, a raw (non-segmented) source video, is implicitly destined for a certain use (or uses), and a recipient (or several types of recipients). It has its own identity, a specific profile, called “authorial” identity which presupposes the existence of an author – individual or collective, identified or anonymous, static or dynamic.

However, under certain conditions, the implicit uses of the video and the variety of its recipients may be extended. Segmentation of the video is one of these conditions. This produces and isolates the audiovisual segments – parts or subparts – whose variety offers multiple uses. Remember that, according to one of the so-called “compositional” semiotic models, from a semantic point of view, a video forms a consistent whole made of a collection of “parts”. Each of these parts can in turn be broken down into subparts. It is the Segmentation Workshop (see Chapter 2) which enables us to extract and subsequently analyze them, either individually as distinct parts, or as a group of parts around a theme, a type of discourse, aimed at specific recipients and uses.

As we shall discover, this section of the Description Workshop enables us to indicate the contexts – e.g. education, research, socio-cultural matters, heritage, digital communication – in which the analyzed audiovisual text may be used to make a genuine intellectual contribution, and become a resource, and by which users are classified according to their age, level of knowledge and social background.

6.1.1. The “genres” of uses of an audiovisual text

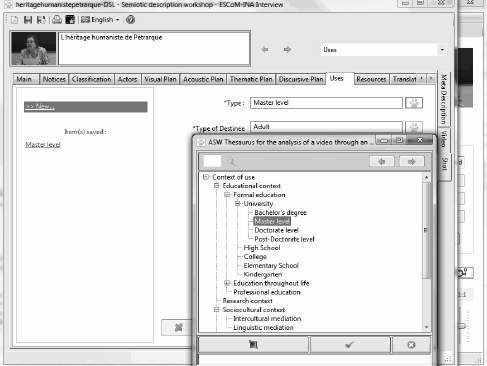

The interface of this section displays the “genre” of use, in the form of a list which is integrated into the ASW thesaurus.2 It also enables us to automatically index the possible uses of the video in a (formal or informal) educational, research, socio-cultural, patrimonial, or digital communication context, as shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1. The interface of the “uses” section: a view of the “genre” tab

When we speak of an “educational context”, we are speaking of both formal and informal education. Formal education is school education – from nursery school to higher education. Informal education (or lifelong learning) corresponds, among other things, to intercultural, scientific, artistic and literary etc. education and to literacy.

Apart from this educational usage, we find uses of the video in varied contexts ranging from intercultural and linguistic mediations to long-term archiving, and, finally digital communication (through portals, Webmail, video-sharing channels, Web 2.0, and Wikipedia).3

6.1.1.1. The educational context: main objective of the ASW-HSS project

As was pointed out in Chapter 3 of this book,4 the ASW-HSS project is mainly oriented at pedagogical uses for audiovisual texts in the context of teaching or (formal or informal) learning. This use was defined, on the one hand, due to the nature of its audiovisual corpus – mainly scientific and educational (interviews of researchers, educators, lessons, seminars, conferences, etc.) – derived from preexisting corpora in the Audiovisual Research Archives program; and on the other hand, it stems from the results obtained during a survey carried out among communities of audiovisual resource users.5

Analyzing this survey enabled us to extract the general trends and expectations audiovisual resource users with a clear propensity for exploiting them in an educational or learning context. All in all, most users favor applications for documenting and informing their own work; self-guided learning remains a secondary priority; other important criteria are teaching and sharing. The availability of documents appended to the videos – such as educational files for example – is essential for all respondents to the assessment as educational and self-learning resources questionnaire.

In addition, the majority of users wanted short videos, of a few minutes (occasionally longer, depending on the use envisaged). From this perspective, the chaptering of the videos, as it is carried out in the Segmentation Workshop, perfectly fulfills these demands. Moreover, this operation enables Internet users to access the video segments they are looking for directly.

The survey highlighted a number of ways of using an audiovisual text, notably in various educational contexts depending on the genre of pre-existing audiovisual documents. Research interviews, lessons, seminars, conferences, etc. serve as additional resources for higher education students and researchers.

However, direct access to the content of the documents is far from guaranteed by Websites which host them – a simple video library, e.g. – or requires the student or researcher to invest time which they do not always have (e.g. to listen to a filmed lecture) because the video is not appropriated, not adapted. This gives rise to one of the main advantages to the ASW-HSS project and its technical and metalinguistic environment, which enables us to extract and isolate video sequences comprising notions, definitions and themes; to collect and combine them in the form of specialized publications dedicated to a specific use and intended for a given recipient. On the one hand, these types of specialized publications favor extremely precise research in raw audiovisual texts, and on the other, offer a specialized, rich and open editorial collection – in the form of educational or thematic folders, classified by domains of knowledge, level of knowledge, socio-cultural level, age, etc.6

A certain number of usage scenarios were produced by each thematic workshop (CCA, LHE, ArkWork) as part of the ASW-HSS project. They were created not only by using the structures developed and tested during other research projects,7 but also by collecting examples of uses submitted by lecturers, students, and visitors to the Audiovisual Research Archives (ARA), surveyed through the Website.8 These scenarios concretely demonstrate how to use an audiovisual text in two situations that we have chosen to address in more detail. The first one relates to the use of an audiovisual text in an educational context and the second, in a context of scientific promotion and communication (see section 6.1.1.2).

6.1.1.2. The usage scenario: a concrete example of educational scenario for the LHE workshop

Here we present the educational usage scenario, elaborated as part of the LHE – Literature from Here and Elsewhere – workshop, dedicated to the diffusion of research on literary heritage and to literary heritage itself. This scenario was based on a video-recorded theater adaptation of The Arabian Nights. The literary genre of the tale being part of the curriculum in French secondary schools, it seemed to us that an original treatment of it in the form of a theater adaptation would be useful to a teacher as a starting point to a series of lessons about the genre “tale”. In addition, the mise-en-scène, combining the narration of the story by a storyteller and musical accompaniment – instrumental and vocal – prompted us to start with a filmic sequence showing the relations and interaction between the narration of a story and the musical accompaniment.

Sites, and educational files or folders aimed at teachers in secondary schools9 were consulted and served as a reference for developing this scenario.

The scenario was constructed based on the video of a contemporary staging of a narrated tale from The Arabian Nights, accompanied by instrumentation and singing.

This source video – entitled “Impossible love according to the Arabian Nights” – holds two advantages for use in education: the first relates to the genre of the tale, the narrative structure of the story with its different stages; the second focuses on the relations between the narration of a text and the music. The aims of these scenarios are based around these two interests. The audiovisual text that we have at our disposal is the raw video of the performance, without chaptering. For the purposes of the scenario, it may be segmented using the Segmentation Workshop,10 following the narrative sequence of the tale, so its structure can be appreciated.

The general educational theme envisaged is the improvement of linguistic and cognitive (descriptive, narrative, argumentative) skills by raising awareness, and an introduction to oral literature, in this case by way of the story, using online audiovisual resources. Introducing oneself to oral literature consists of understanding the structure of a story, how it is written, so as to be able to reproduce another similar story, both on an individual and collective basis. In the meantime, the pupils can learn to communicate correctly and adequately in their mother tongue, both orally and in writing, by writing essays and participating orally in classes. In addition, the regular presence of instrumental and vocal music throughout the recital enables us to examine the relations between the story and the music. Finally, this individual and collective work about the tale, and the example of the filmed adaptation of “Impossible love”, may serve as a starting point to an original group theatrical creation in class.

To realize these objectives, the educational scenario suggests a series of five sessions, spread throughout the academic year at the teacher’s convenience. These five sessions are a suggestion to the teacher, a model for use of this filmed theatrical adaptation in class, which also holds true for any other artistic representation of this genre.

The first session aims at improving written expression in the pupils’ native language. The practice starts with having the students watching the video, after a brief introduction to the tale by the teacher. This is active viewing during which the pupils take some notes and observations, then write a free essay reflecting on what they have learned from the video (the content of the tale and the audiovisual content).

The second session focuses on training for oral expression in the native language (in this case, English). The video is a starting point for a discussion in the form of oral questions about the representation or the mention of places, objects, etc. as they are shown or suggested in this theatrical adaptation. This discussion is fed by related iconographic research done in class (geographical maps, artwork illustrating different points in the collection of the Arabian Nights tales, etc.) thereby introducing the students to research techniques and comparison of documents from various sources.

The third step is marked by the revelation of the particular structure of the tale, based on which the pupils have to write a summary, at home, in keeping with this structure learned in class.

The penultimate session addresses the rhythmic relations between the story and the music: the teacher selects short relevant passages where the music and the singing accompany the story in a meaningful way. The objective is to uncover the role of music and singing in oral literature, the interaction between the music and the text, and between the musical rhythm and the rhythm at which the text is recited. This is another pretext to reveal the role played by the choice of instrumentation and compare the use of music and song through the ages. The pupils are once again encouraged to make oral contributions.

The fifth and last session, which concludes this cycle, sets the wheels in motion for a collective project consisting of writing a story in class, with the aim of putting on a show at the end of the year.

This type of scenario only gives us a brief glimpse of the possible uses of an audiovisual resource, especially in a context limited to education and to an audience of schoolchildren. It is only one of the many other possible examples of uses of this audiovisual resource that the analyst may imagine, in other contexts of knowledge-sharing.

6.1.1.3. The context of communication/valorization: an example of heritage valorization

Another usage scenario for the audiovisual text developed as part of the ASWHSS project is valorization. Although the raw audiovisual corpus of the ASW is mainly and originally dedicated to educational use, it is possible, using the ASW environment, to broaden its usage. Thus, the choice of sequences when cutting the video in the Segmentation Workshop may enable the segments to be put to another use, addressed to a different audience. Cutting transforms the initial complete video, considered as a coherent whole, a functional and hierarchically integrated network of “parts”, into a smaller video which is however still understood as a consistent whole.

To illustrate our idea, we shall take the example of a report on an “Archeological rescue in Seine-Saint-Denis”.11 Yves le Bechennec, the archeologist and heritage mediator, manager of the archeological site of the Château de Ladoucette in Drancy (near Paris, France), tells us about excavations in preventive archeology, the methods employed in this discipline and his approach to getting the local people to take part in this archeological activity, so as to encourage them to take possession of the history of the place they occupy. The ArkWork workshop,12 which is a multilingual portal about archeology and one of the three pilots of the ASW-HSS project, has extracted a sequence from the video with the objective of valorizing and promoting the patrimonial interest of this event as regards the city, the district and even the region. The scenario envisages a short video – two to four minutes in total – a slide show of a few photos taken from the original audiovisual text, illustrations, shots, so as to raise awareness and inform both ordinary citizens and the public and private institutions responsible for managing the cultural heritage of the city, district or region (see Figure 6.2). A short textual presentation of the report accompanies this sort of “promotional video”.

In addition, this type of communication fits perfectly as support for an exhibition, either on the archeological heritage of the city, or more broadly of the district or region, or even Gallic heritage in France.

Here let us make a comment on the distribution of this video. Whatever the use, the deliberately short format of the film enables us to distribute it in the form of Webmail, video-mailing, and on various social networks (see [STO 12a]).

Other applications of this scenario dedicated to promotion and communication are conceivable for all sorts of audiovisual texts which lend themselves to this type of heritage-related use.

Figure 6.2. “Archeological rescue in Seine-Saint-Denis”

6.1.2. The target audience of an audiovisual text

As we have stated, the (audiovisual) text has a specific identity to begin with, which can be transformed using the ASW Studio enables us to transform it, and a real or imagined audience, which may also be adjusted depending on the changes carried out on the original video. It is this second section – “Uses” – that we shall now address.

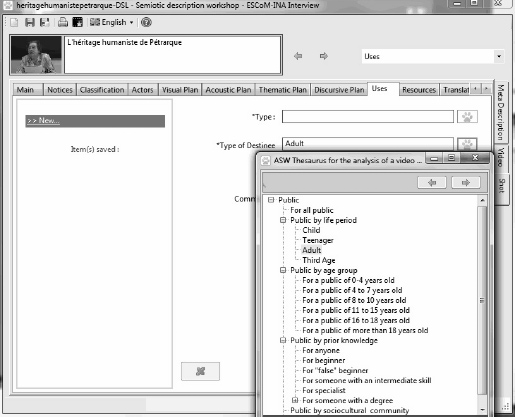

The access to a directory of the different types of recipients of the video opens in the general form of the “Uses” section. Figure 6.3 shows the different types of audiences, classified into “all audiences”, or by period of life – from childhood to adulthood – by age-group, by level of knowledge (from beginner to specialist), by their qualifications, by socio-cultural communities, and finally by socio-professional categories.

Many documents in the ASW-HSS audiovisual corpus are originally intended for an education or research context, of at least Bachelor level. Several options are presented to the analyst when he begins the description/indexing of a video. Either he keeps the type(s) of recipients attributed to the initial video, or he modifies them, e.g. by adapting this video to a new recipient.

The publications of the ASW-HSS project are mainly aimed at researchers and students for didactic use, but also at “professionals” who rely on research in human and social sciences, such as journalists, socio-cultural mediators, publishers, etc.

Figure 6.3. A glimpse of the section opening on the tree view of the recipients

6.2. Producing a linguistic adaptation of an audiovisual resource

The ASW Workshop of Description, by way of the software Interview, facilitates a multilingual use of an audiovisual collection which is originally monolingual, in order to reflect either the international nature of the contributions being archived or the intrinsically multilingual nature of the Internet audience.

The organization of the software enables us to play on this reciprocal relation between translation and adaptation. Indeed, how is one to go about adapting a monolingual resource to a multilingual environment? Based on the original language, the software suggests possibilities so as to offer understanding and distribution according to a foreign-language audience.

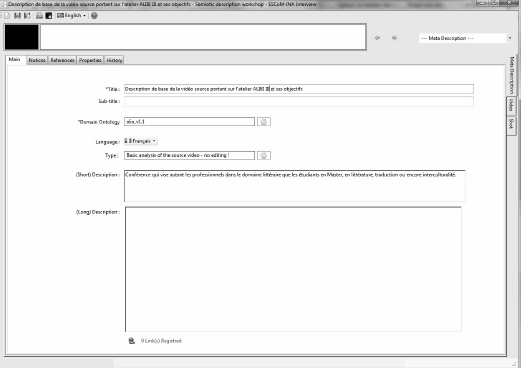

The “Metadescription” section enables the analyst to make an initial choice of the language of description that he will use throughout the analysis. Obviously, this language may be different from the language of the audiovisual discourse. Thirty-five languages are suggested. The translation work is carried out primarily on the metadata and not on the specific content of the video (see Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4. Choice of language in the “metadescription” section

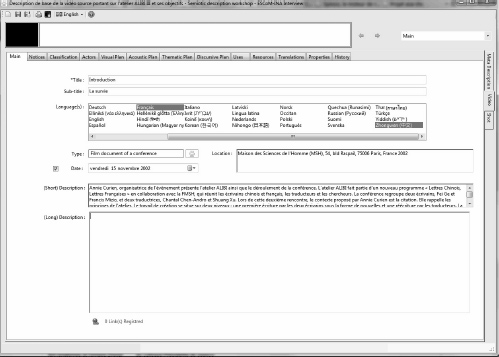

However, in the “Video” and “Segment” tabs, the box Language(s) designates the language(s) in the audiovisual discourse. Unlike in “Metadescription”, there is the possibility of choosing several languages by clicking on the options in the box, in the case of a multilingual video. This is particularly useful for bilingual exhibitions such as the ALIBI (Atelier Littéraire Bipolaire [strictly, Bipolar Literary Workshop])13 workshops implemented by the Chinese Research program of the FMSH (in Paris). Some of these exhibitions are available for consultation on the LHE14 portal. The ALIBI workshops study the issue of literary translation between French and Chinese. The conferences organized in the context of the ALIBI workshops are conducted in both languages, the contributors’ words being relayed by interpreters (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5. Choice of language(s) in the “video” section

Thus, on the one hand, we have the monolingual language of description, and on the other, we have the original languages that will have to be adapted to a particular recipient.

The issues of the translation/adaptation of audiovisual discourse are dealt with, in the ASW workshop of description, by the “Translations” section. This section offers five genres of translation/adaptation of the audiovisual content:

– summarizing translation, which consists of writing a summary of the discourse in the “target” language;

– telegraph-style translation, which consists of freely choosing a number of keywords;

– literal translation, faithfully rendering all the discourse filmed in the segment;

– translation-adaptation, which allows the target audience’s social/cultural context to be taken into account. This type of translation is therefore complemented by explanations about any cultural references and additional information aimed at the target audience;

– free translation, which is the freest of all the options for translations /adaptations, as long as the “spirit” of the content of a segment is respected. This may be used, e.g. by a writer whose target language is not his native language.

These different genres of translation show that practices relating to the issue of translation are rather inclined towards adaptation. The analyst’s task is not to carry out a literal translation of the audiovisual discourse but to reflect on its content and adapt it to a given audience through written language (see [STO 07]).

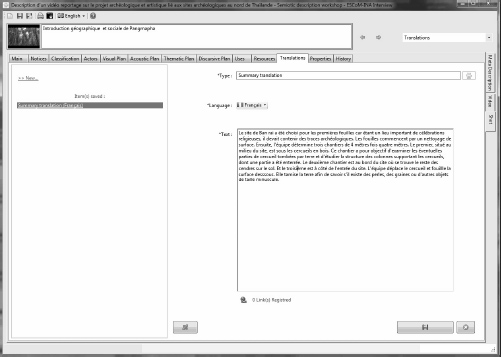

Thus, we had to adapt a Thai video-report about the saving and valorization of archeological sites in Northern Thailand15 to an English audience. The issue with the content of this video-reportage stems from the cultural context, which must be made explicit. Hence, the translation-adaptation of a first segment entitled “Geographical and social introduction to Pang Mapha” transposes the poetic commentary of the audiovisual discourse into a technical description concentrating on the information rather than the tone (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.7 shows us a small extract from the original discourse in Thai (literally translated into English) and the version we have indeed chosen so as to make it understandable to the English audience interested in the geographical and social context of the Pang Mapha, which is a small district of the province of Mae Hong Son, located in the north-west of Thailand.

This idea of creating linguistic versions of a source text which are adapted to a target audience is in keeping with the idea developed by Slodzian [SLO 07] in her article “Rationalization of Languages and Terminology”. The author makes the important distinction between the terminologies that the translator has to confront in any scientific text: “terms vs. ordinary words and technical sub-language vs. ordinary language”. By replacing the scientific vocabulary with prosaic vocabulary, the translator makes an initial choice of adaptation for an uninformed audience. She suggests a vulgarization of the scientific language so as to communicate with a broader audience, at the expense of the accuracy of the terms.

Figure 6.6. “Translations”

Figure 6.7. Example of a translation of the Thai film

Let us return to the practical procedure enabling us to carry out a translation/adaptation using the ASW Description Workshop. The analyst wishing to carry out the translation/adaptation of an audiovisual segment first selects the language (the output language), in the interactive working form. Then, he uses the Text field to write his own appropriate text.

One interesting case is the following: it is highly possible to produce an appropriate translation-adaptation for each segment identified by the analyst (i.e. appropriate as regards the analyst’s objective, which he attempts to fulfill by choosing and carrying out a specific type of translation-adaptation – see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8. Segmentation of the video and translation of the segment

Let us go back to our example of translation/adaptation of a Thai video-report about archeological heritage in the north of the Thailand.

In order to enable the English audience to understand the recording (archeological sites, objects, nature, etc.) making up the visual shot of the video-report, the analyst may choose to systematically use a linguistic depiction of the type Summarizing translation.

By choosing this option, the analyst will create sorts of summaries of the visual scenes in English and convey the information developed in these directly to the English audience without taking into account the discourse itself in Thai, the communication objective of which is entirely different. In other words, the analyst will have created a new version of the report (from a linguistic point of view and also with a different message). Thus, this is a concrete example of what we call documentary “re-purposing” both the necessary know-how and technique to open up monolingual and culturally-rooted texts to an intrinsically multilingual and culturally diverse audience, as is the case for the Internet or Web 2.0 audience.

Similarly, the telegraphy-style translation genre simplifies the structure of the discourse while keeping the keywords. The literal translation genre on the other hand consists of reconstituting the specialist’s discourse word for word. More extensive simplification in the translation-adaptation genre enables the analyst to address it to a defined audience. This approach is not a transcription of the discourse but rather a “retransmission”. The analyst explains terms which are specific to the scientific discourse, and cultural references linked with a topic. Finally, the free translation genre engages the analyst’s explicitly demonstrated subjectivity as regards the discourse. The content is subjected to a new point of view. Here, the language is not the only parameter at issue. We also have to deal with the specificity of the topic, as well as the transmission of information itself between audiences belonging to different cultures.

Here we have, then, a brief presentation of the approach used in the ASW-HSS project to deal with the central issue of documentary re-engineering.

1 Chapter written by Muriel CHEMOUNY and Primsuda SAKUNTHABAI.

1 See the explanations relating to Common knowledge, in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, article by Peter VANDERSHRAAF and Giacomo SILLARI: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/common-knowledge/.

2 For further explanation see [STO 12b].

3 For further explanation see [STO 12a], Chapters 6, 7 and 8.

4 [STO 12a], see 3.2.2.2.

5 This survey was carried out at the very beginning of the ASW project, to determine the profile of the users. Each thematic workshop, CCA (Culture Crossroads Archives), ArkWork (Arkeoanaut’s Workshop) and LHE (Literature from Here and Elsewhere), created a questionnaire aimed at three different groups of users (lecturers, students and professionals in human and social sciences) enabling us once we had analyzed the responses to assess the expectations and needs of these users. The details of each survey are available for consultation on the ASW Website, at: http://semioweb.msh-aris.fr:8080/site/projets/asa/spip.php?article52.

6 For more information, also see Chapter 3 of this book.

7 These are two European research projects: CHIRON, a project dedicated to a systematic analysis of the new paradigm names “u-learning” (ubiquitous learning) i.e. learning anytime, anywhere. See the Website of the project http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/Chiron/. The second project, LOGOS, (led by the former Hungarian television company Antenna Hungária), consisted of creating scenarios for a contextually adapted use of pre-existing multimedia digital resources.

8 http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/FR/_survey1.asp: this link corresponds to the first page of the questionnaire. Please also see the subsequent pages.

9 The “Cercle Gallimard de l’enseignement” [Literally, “Gallimard Circle for teaching”] offers educational files – see http://www.cercle-enseignement.com/College/Sixieme/Fiches-pedagogiques/L-epopee-de-Gilgamesh. For the tales, refer to the files of the Regional Center for Educational Documentation (Centre Régional de Documentation Pédagogique – CRDP) of the Académie de Creteil: http://www.crdp.ac-creteil.fr/telemaque/comite/contes.htm.

10 For details about the Segmentation Workshop, refer to Chapter 2 of this book. The stage of segmenting the said text is dealt with in Chapter 1 of [STO 12a].

11 The audiovisual text is available at the two following addresses: CCA http://www.archivesaudiovisuelles.fr/1625/ and ArkWork http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ada/1668/.

12 See: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ada/FR/Default.asp.

13 The ALIBI Workshop is an initiative of the Chinese Program of the FMSH, managed by Annie Curien, who is a sinologist, translator and researcher in contemporary Chinese literature at the CNRS (see the page regarding ALIBI on the Website Lettres Chinoises-Lettres Françaises (Chinese Arts–French Arts): http://www.lettreschinoises-lettresfrancaises.msh-paris.fr/fr/alibi_Prog1.htm.

14 http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ALIA/FR/.

15 This is the report entitled ![]() From (Different) Horizons of Rockshelter”, distributed on the ArkWork portal: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ADA/1909/home.asp.

From (Different) Horizons of Rockshelter”, distributed on the ArkWork portal: http://semioweb.msh-paris.fr/corpus/ADA/1909/home.asp.