Chapter 5

Analysis of the Audiovisual Content 1

5.1. Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a particular approach for processing a text (in our case, an audiovisual one). This approach focuses on the content of the text, and on the supposed “meaning” it holds for the author or for a given audience. In order to develop this approach in concrete terms in the form of a (central) part of the working environment which we shall call the ASW Description Workshop (by way of reference to the R&D project for which it was developed), we have relied on a number of basic hypotheses.

First, we consider that a theme is a piece of knowledge which enables some agent to understand the world around it, to interpret it, interact with it, with other agents and also with himself. Similarly as for visual art, the theme may be compared to a frame which determines an agent’s view of the world, of others and of himself, the empirical scope of a view, his (epistemic but also social and historical) point of view, and even his (cultural, cognitive etc.) assumptions. A theme – an intellectual frame – is, of course, subject to processes of adaptation and evolution which result from interactions between agents, and between agent(s) and the world.

When speaking about the theme (or a theme) developed and addressed in a text, we are suggesting thereby that a text communicates something about an object or a domain to which it refers, making use of the frame which is peculiar to the theme. Hence when, in an audiovisual recording, it is question of the Aymara language, the latter constitutes the referential object (see section 5.4) but it may also be thematized (or framed, so to speak) very differently: as an object of linguistic description, a historical object, a political object, an object in relation to other considerations, etc. Thus, by way of the process of thematization, the referential object becomes the subject of the text or discourse which deals with the aforementioned object. The referential object itself acquires the status of a “material” that the author uses in a similar manner to the way in which a painter or novelist uses a historical personality as a (narrative) character integrated into a story or a painting.

A referential object which constitutes the “material” of a subject is therefore only accessible to us in a thematized form or in the form of a theme of discourse, a frame chosen by the author in order to speak of such-and-such an object. The Aymara language “in itself”, is something that we suppose exists but will never become the topic of a text or discourse – it is only as a framed object, as an object of knowledge, hence as a thematized object, that it becomes so.

Nevertheless, the thematization – the framing – is only one aspect of the work which aims to make an object, a domain, understandable according to its author’s point of view. Other aspects are more particularly concerned with the way of seeing or processing a thematized object: highlighting a specific detail, choosing an angle, showing the object through the eyes of another, and so on. All these operations aim at explicitly expressing the author’s particular vision of his object. They are at work in any text, be it a literary or artistic text, an “everyday” text, a scholarly text or, on the contrary, a practical or utilitarian text, and regardless of whether it is an audiovisual or a verbal text.

This means that any even slightly-sophisticated analysis has to take account of the enunciative and discursive context in which a thematized object is processed and developed as well as the different possibilities for its multimodal expression, its audiovisual mise-en-scène.

We therefore have – in the space of a few sentences – the general framework for understanding the thematization and the discursive and audiovisual processing of an object, or domain of knowledge/expertise, by the text (here, the audiovisual text). This framework has guided us in defining and elaborating models of thematic description of audiovisual corpora.

Theoretically speaking, a model of description relies upon a hypothesis of what could be the structure, or the organization of the subject addressed in an audiovisual text if this topic comes from a given domain of knowledge.

Practically speaking, a model of description “serves” the analyst in order to identify and describe the parts which are relevant to his audiovisual corpus. “Relevant parts”, here, means the segments or passages of an audiovisual text which add concrete information to a given model of description. Let us briefly take the example of one of the models of thematic description in one of the fields of experimentation of the ASW-HSS project, entitled “(Identifying and describing) the daily practices explained and/or shown in the audiovisual corpus”.

This model, as we shall see later on, is made up of a set of criteria of analysis which initially guide the analyst in order to identify the passages – the segments – in his corpus where it is indeed a question of a particular daily practice, or in which a particular daily practice has been recorded. Secondly, the analyst uses the criteria from the model in order to index the content of a segment (passage) identified as relevant. Thus, if the analyst identifies a passage in his corpus where we witness a lively discussion between several individuals around a table in a café and if he believes this situation to correspond to the theme of “daily practice”, he can index this segment according to the criteria stipulated by the model: type/genre of the daily practice, participants, frame, topic, aim, etc. If, however, the analyst does not believe this situation falls within the theme of “daily practice”, he will not consider it, or will take account of it using another model of thematic description.

This example demonstrates the function and status of a model of description in the process of analyzing an audiovisual corpus: it defines a possible thematization of a referential object (here, an object which the analyst “sees” or “hears” while watching a video). A library of models of thematic description would therefore take account of all the thematizations deemed relevant in the context of a project of analysis or publication/diffusion of knowledge.

The model of description is part of what we call the metalanguage of description, which is used to describe an audiovisual corpus and, more generally, to properly conduct an analytical project (description, indexing, publication, etc.).

Depending on their particular empirical scope, we have to distinguish between different types of models of description which present themselves as the interactive working forms in the ASW Description Workshop. Hence, in Chapter 4, we looked at models of description for analyzing the visual and acoustic expression of audiovisual corpora. Chapter 3 was devoted, among other things, to models of description enabling us to define the paratextual identity of an audiovisual document (title, author, genre, rights, etc.). We also looked at models of description which are not used to describe an audiovisual corpus but rather to explain the content and the objective of the analysis itself. These are the models we use to produce what we call a metadescription and which deal with the analysis itself, rather than the audiovisual text (see Chapter 3). In the next chapter (Chapter 6), we shall discover a set of models of description with that serve us to analyze the “pragmatic” aspects of an audiovisual text or corpus.

This chapter, however, is given over to a brief overview of the models of description that we use to describe the content of an audiovisual corpus, i.e. the topics or themes which interest the analyst or the players involved in an analysis, and for which the analysis brings his expertise to bear (for a more specific presentation of the description of audiovisual archives, see [STO 12b]).

5.2. A concrete example of the description of a topic

Let us start by discussing the concrete example of a model of thematic description. As we have just stated, and similarly to the analysis of audiovisual shots (see Chapter 4) or the pragmatic profile of an audiovisual text (see Chapter 6), the analysis of the topic(s) of a filmic text is also carried out using predefined models of description but which can always be adapted to the author’s and stakeholders’ needs and interests.

Technically speaking, a model of thematic description is a configuration of conceptual terms (of “concepts”) that the analyst must adapt to the peculiarities of the object of his analysis. This adaptation takes the form of a set of tasks of analysis.

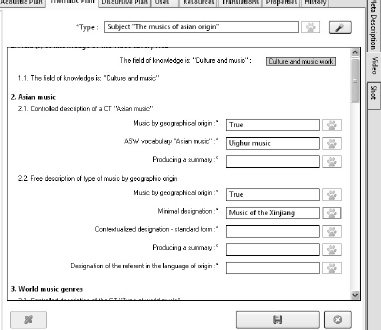

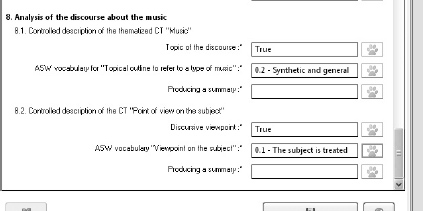

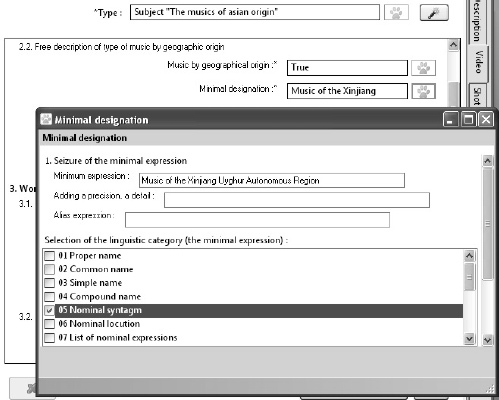

Figures 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5 exemplify the tasks that the analyst may carry out if he wishes to describe, e.g. the content of a video dedicated to a particular genre of music of the world. They show us extracts from an interactive working form which constitutes the interface [STO 05] between the analyst and the model of description. The interface is made up of several regions, which are easily recognizable from a visual point of view.

Among these, we find “great regions” or “major regions” dedicated to the sequences which make up the model of description. A sequence forms a functional part of the model. It addresses a particular aspect of the description of an object. Thus, Figure 5.1 shows a region entitled “Description of Asian music”, Figure 5.2 a region entitled “Description of the genre of music”, while Figure 5.3 shows a region entitled “Geographical location”, and so on. The three regions indeed show three particular aspects of the object of description entitled “Asian music”. Each aspect of the object of description is defined by a functional sequence of the model that the analyst is using, via his working interface, to describe the audiovisual texts addressing the topic in question, i.e. the topic of “Asian music”.

A region making up the interface of an interactive working form comprises “sub-regions”, i.e. local zones corresponding to one or more specific features of the model of description. As we shall see later on, these deal mainly with two central aspects of the activity of analysis per se, namely:

1) identifying what is being analyzed;

2) the procedure of analysis itself.

Figure 5.1. First extract from the interactive working form for describing a topic belonging to the domain “culture and music”

Figure 5.2. Second extract from the interactive working form for describing a topic belonging to the domain “culture and music”

For example, Figure 5.2 shows that the interface of the region “Description of a genre of world music” is made up of two more-specialized zones: the “Controlled description …” and “Free description….” This means that the region “Description of a genre of world music” is reserved for the analysis of the specific object “genre of world music” – quite in contrast to, e.g. the region called “Description of Asian music” (Figure 5.1) which is reserved for the analysis of the object “Music by geographical origin”. The analysis of the specific object that is the world music is carried out either by a controlled description (i.e. using a thesaurus, see section 5.5), or by a free description, or even by both of these. However, these two possible procedures for describing the specific object “Genre of world music” form the content of the two zones making up the working interface for describing a genre of world music (Figure 5.2).

Figures 5.1 to 5.5 show the concrete example of the description of a topic addressed in an interview with the French ethnomusicologist Sabine Trebinjac, carried out as part of the ARA program in 2007.1 The topic was the Uyghur Muqam, which is a type or genre of music played, among other places, in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (also called Chinese Turkestan), in Western China. The Muqam is part of the Uyghur musical traditions which have developed their own local variants, such as the rak or the bom bayawan.2

The working form constituting the interface between the analyst and the appropriate model of description for analyzing the topic in question allows the analyst to proceed in stages:

– first, to start identifying and describing the geographical origin of the music genre;

– then, to express the music genre itself as well as its different contextual characteristics;

– further to appraise the way the topic is addressed and developed in the video being analyzed;

– to localize the music genre in question, both geographically and historically.

Figures 5.1 and 5.2 show us the first stage in describing a topic dealt with in an audiovisual text being analyzed. This encompasses the three underlying sequences of the model of description which we use in order to clarify (1) the domain of knowledge/expertise and (2) the specific objects “in” that domain.

In our case, the domain of knowledge/expertise is predefined – it is “Culture and music”. Identifying the domain of knowledge is the very first stage in the thematic analysis of our corpus.

Figure 5.1 also shows us the second sequence making up the model of description for analyzing world music. This second sequence, represented by the part of the working interface called “Description of Asian music”, invites the analyst to clarify the object (or a part of the object) concerned with the domain of knowledge “Culture and music”. Here, it is a question of specifying the geographical origin of the type of music in the audiovisual text being analyzed. In our concrete example, this is Uyghur music.

The task of analysis is made up, here, of two procedures of description: the first one is called controlled description, the second free description. Controlled and free description are the two most central procedures of description in analyzing audiovisual corpora in the context of the ASW-HSS project. We shall come back to them later (see section 5.5).

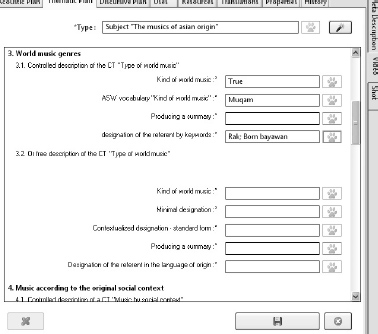

Figure 5.3 shows the third sequence of the model of description represented by the region of the working interface entitled “Description of a genre of world music”. In other words, this part of the interactive working form is dedicated to the identification and description of the musical genre which is presented in the video being analyzed. In our case, it is the Muqam as it is played in western China in the form of two local variants: the rak and the bom bayawan. Formally speaking, this sequence is perfectly similar to the sequence for describing the music from the point of view of its geographical origin – once again, it is made up of the two procedures of description that we met earlier: controlled description and free description.

However, in comparison with the second sequence (Figure 5.2), the third sequence (Figure 5.3) allows us to add extra information regarding the understanding of the object being analyzed. In other words, in the model of description, we assume – that is, the knowledge engineer or the concept designer assumes – that if we speak of a sort of world music in an audiovisual text, we probably either discuss its geographical origin or its particular genre, or possibly both. Therefore the analyst may have recourse either to the second sequence (Figure 5.2), or to the third sequence (Figure 5.3), or to both, depending on the peculiarities of the object.

The three sequences that we have just briefly discussed, along with other sequences which we will not be discussed here, form the functional part of any description scenario dedicated to the analysis of a particular type of object of description, i.e. a domain of knowledge/expertise (see section 5.4 for more detail). Such an object of description is processed using procedures of description (including the controlled and free descriptions) in one or more sequences making up a given model of content description. We will come back to this later.

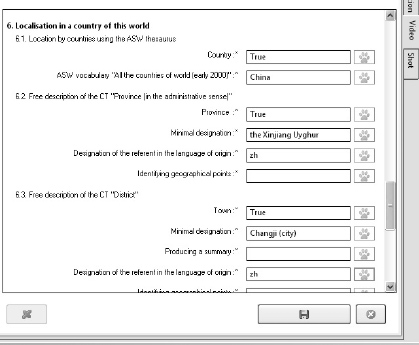

Figures 5.3 and 5.4 show the regions of the interactive form which represent the sequences of the model of description reserved for the referential contextualization of a thematized object of knowledge in an audiovisual corpus.

Figure 5.3. Third extract from the interactive working form for describing a topic belonging to the domain “culture and music”

Figure 5.3 provides an example of the sequence aimed at geographically localizing an object of knowledge. In our concrete case, we localize the Muqam music genre, which is part of the Uyghur musical traditions. In the interview with the ethnomusicologist Sabine Trebinjac, one of the geographical locations is the city of Changi in the Uyghur Autonomous Region. The temporal contextualization, represented by Figure 5.4, identifies the period from 1980 to 1995 as one of the chronological periods of the evolution of the Muqam, thematized and developed in the interview.

It should be recognized that a distinction must, of course, be drawn between (a) the times and places which are relevant in order to localize the object (event, situation …) dealt with in an audiovisual document, and (b) the time and place that the audiovisual document itself was created – in our case the “place” and “moment” when the interview with Sabine Trebinjac about the Uyghur Muquam was carried out). The second case is dealt with as an aspect which is specific and peculiar to the paratextual profile of any audiovisual document being analyzed (see Chapter 3).

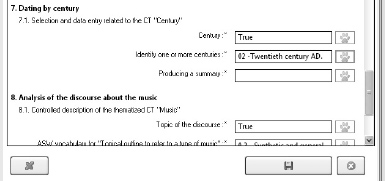

Figure 5.4. Fourth extract from the interactive working form for describing a topic belonging to the domain “culture and music”

Figure 5.5. Fifth extract from the interactive working form for describing a topic belonging to the domain “culture and music”

Figure 5.5 shows another functional type of sequences which may be part of a model of description. This is the type of sequences reserved for analyzing the enunciative and discursive context in which an object of knowledge/expertise becomes a topic or theme of discourse [STO 01] per se. The example given by Figure 5.5 is very simple. Nevertheless, it corresponds to certain level of analytical sophistication which is only rarely attained nowadays in the context of the projects of description of audiovisual corpora destined for distribution on a Website.

This is to enable the analyst, if he so desires, to clarify the point of view from which the topic has been addressed (if, for example, Sabine Trebinjac only deals with her own point of view, if she quotes other sources, etc.). It also enables us to point to the aspects on which the work focuses: on the topic of the Uyghur Muquam, does Sabine Trebinjac offer a general and/or historical and/or comparative presentation? Does she favor a presentation which is “internal” (i.e. solely musical) or “external” (dealing with political, ethnical, linguistic factors) … and so forth. This type of sequences indeed enables us to analyze what we call “held discourse” (“discours tenu”, in French).

As has already been mentioned, the type of sequence represented in Figure 5.5, used for describing the discursive context of a theme of discourse, is relatively simple. Its main advantage is that it enables the analyst to clarify the specificity of the approach to the topic (i.e. general or specialized approach, historical or comparative approach, etc.).

Nevertheless, as part of the ASW-HSS project, we have been able to elaborate a library of sequences of held discourse analysis – a library which, should the need arise, will enable us to quickly create models of thematic description incorporating sequences of analysis of the enunciative and discursive context that are far more sophisticated than the one presented in Figure 5.5. For example, a type of sequences which is more particularly interesting to us, and that we are testing with our students,3 has been elaborated so as to take account of the connotative aspects characterizing amateur videos about everyday life (with family or friends, on holidays …) and which constitute an outstanding testimony to the ambient and emerging socio-cultures the world over.

Here we end our discussion of a concrete example of a thematic analysis of an audiovisual passage using an interactive form. However, it should be added that the models of thematic description conceived and tested as part of the ASW-HSS project encompass other types of sequences facilitating a far more in-depth analysis of the content of an audiovisual corpus. In particular, these are sequences which are functionally specialized in the analysis and description of the audiovisual expression of a topic/theme, and “comment” sequences enabling us to focus on an analysis, to discuss it further, to make freer and more personal and unconstrained interpretations, etc.

Similarly to the models of audiovisual description (see Chapter 4), the sequences for analyzing the expression of a given topic by visual and/or acoustic means are also built around a set of particular aspects to be analyzed, such as the visual (or sound) point of view, visual (sound) framing, the camera movements, the different types of visual shots, etc. However, in the context of thematic analysis, these aspects help to underline the way in which a given topic is imaged and soundtracked. Certainly, in the case of an interview, this criterion is often only of secondary importance. However, it may become extremely important when filming “real-life” situations, events, people, environments etc. which will then be edited with a view to (also) non-verbally conveying a message (an idea, a vision). It is obviously unavoidable when analyzing subjects (themes or topics) drawn from fictional audiovisual works.

However, it must be stressed that while there is a structural similarity in the audiovisual aspects which can be subjected to an analysis, the audiovisual analysis (Chapter 4) and the analysis of the visual and/or acoustic expression of a topic, have towards two different goals: the audiovisual analysis gives priority to the analysis of visual and sound shots, transitions between shots and visual or sound effects at the expense of a systematic and in-depth analysis of the topic; the analysis of the visual and/or acoustic expression of a topic is part and parcel of the analysis of the content of a corpus where it specifically addresses the ways and strategies of the “audiovisual mise-en-scène” of topics or themes. In this sense, the analysis of the audiovisual expression of a topic or theme is functionally similar to the analysis of the enunciative and discursive context mentioned briefly above (see Figure 5.5).

Finally, an analysis in the form of a comment on a topic or theme is structurally similar to a metadescription (see Chapter 3) but, again, we must make a distinction between them, not only as regards the functional viewpoint but also as regards the scope of the analysis: the metadescription is a comment made by the analyst on the work of analysis in its entirety, whereas the analysis in the form of comments only concerns the topic (theme) being analyzed.

The analysis in the form of comments is particularly useful for stating, discussing and justifying interpretations, but also for discussing the importance of a topic, noting the limits and asking questions about the analysis carried out, etc. We very willingly use this type of analysis in an educational context: offering students an insight into reading and interpreting images. Another use of this type of analysis is made in the context of the experimentation workshop PCIQ (Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Quechua – Quechan Intangible Cultural Heritage)4 where it is used for vindicating the status as heritage (as defined by UNESCO) of a work, a practice, a concrete or symbolic art expression (see STO 12a).

5.3. The model of thematic description

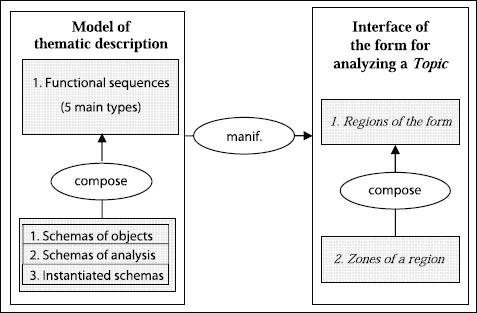

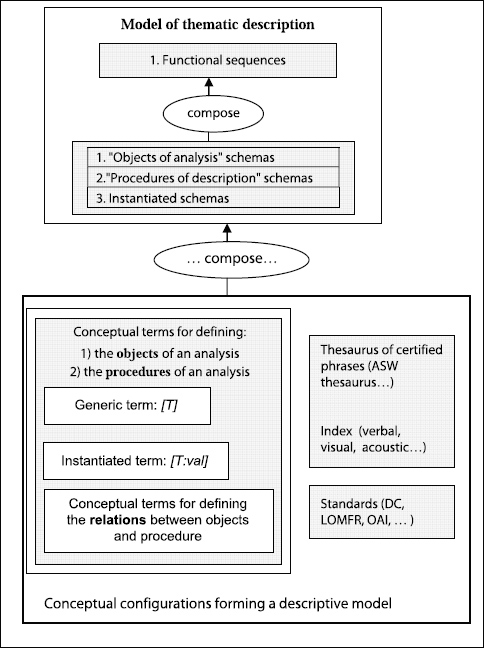

Having discussed a concrete example of the use of a model of thematic description to analyze the content of an audiovisual corpus, we shall now take a closer look at such a model. Figure 5.6 offers an overall view of the whole conceptual organization which determines, on the one hand, the relationships between the model of description and the form for analyzing a given topic, and on the other hand, the internal organization of the model of description.

Figure 5.6. Internal organization of a model of thematic description and relationship with the interactive working form in the ASW description workshop

Remember that a topic is the “matter” which someone – be it an individual, a group, an institution – is interested in, and which leads them to watch or listen to an audiovisual text, to explore it. In the context of an analytical project, the topics are known in advance. They are defined in a library of models of thematic description (see section 5.7).

Hence, an important part of the analyst’s work consists of identifying the relevant “parts” of an audiovisual corpus and appraising them (describing, evaluating…) using an appropriate model of description made available to him, and that he can use thanks to a specific working interface made up of interactive forms (see Figure 5.6).

As Figure 5.6 also shows, the models of thematic description we work with in the ASW-HSS project are made up of functional parts called sequences. We can distinguish five types of sequences, which determine the composition of the models of audiovisual content description:

1. sequences reserved for describing an object in a domain of knowledge (“objects” such as, e.g. musical genres, music by geographical origin, the types and forms of music according to the context of usage, etc., which are part of the domain of knowledge/expertise of the CCC workshop of experimentation5);

2. sequences reserved for referentially contextualizing (in terms of spatial location, temporal location, etc.) an object identified as belonging to a domain of knowledge (e.g. geographical contextualization of a musical activity by country, region or community);

3. sequences reserved for pinpointing the enunciative and discursive context which transforms an object into a topic or theme of discourse (e.g. highlighting the perspective from which the author deals with the subject of a particular musical genre);

4. sequences reserved for pointing out the audiovisual expression of a filmic object (e.g. the visual or audiovisual framing of a concert);

5. sequences reserved for the analyst’s comments relating to his analysis, so as to clarify his point of view, interest, references, etc.

These five types of ASW sequences of description form the structure for a library of predefined sequences which we use in order to define a particular model of the content of an audiovisual corpus (see [STO 12b] for more details). Obviously, not all models of description necessarily have to incorporate sequences from each of these five types, but any model will comprise at least one sequence belonging to the first type, i.e. one of the two sequences shown by Figures 5.1 and 5.2.

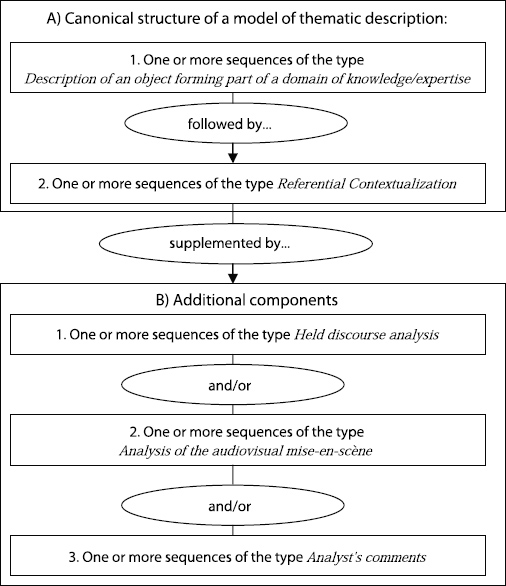

As Figure 5.7 shows, a model of thematic description is canonically composed of one or more sequences of the type Description of an object forming part of a domain of knowledge/expertise followed by one or more sequences of the type Referential contextualization of the analyzed object. This canonical structure of a model of description can be “enriched” by sequences derived from the three other types identified below: Analysis of the held discourse, Analysis of the audiovisual expression and Analyst’s comments.

Figure 5.7. Internal functional organization of a model of thematic description in the form of a series of specialized sequences of description

In principle, a sequence making up a model of thematic description may itself be broken down into two or more sub-sequences. The decomposition of a sequence into several sub-sequences becomes essential, for example, if we are seeking to create models of specialized thematic description offering the possibility to take account of the (real or assumed) internal organization of an object of knowledge.

This is the case, for example, when we are intending to describe not only a social practice such as a ritual or festival (merely naming it and writing an unstructured textual summary of it) but also, to enable the analyst to state, among other characteristics, the roles associated with a festival or ritual, the objects of use, the sequence of events making up a festival or ritual, the meanings and interpretations attributed (by the participants themselves) to such a practice, etc. Such a deconstruction must, however, be undertaken with a great deal of circumspection, in view of the high complexity of the resulting model of description.

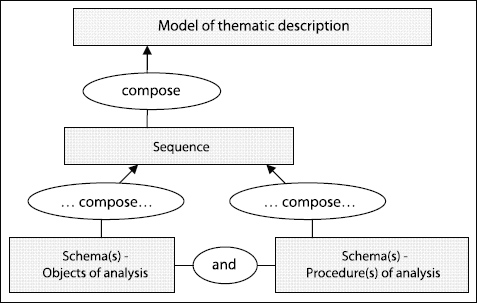

This being the case, as can be seen in Figure 5.8, any sequence – whether broken down into sub-sequences or not – has at least two types of components: (1) the schema “object of analysis” and (2) the schema “procedure of analysis”. A third type of components – called instantiated schema (see Figure 5.6) – is optional (we will discuss this in section 5.5).

Figure 5.8. Structural internal composition of a sequence of thematic description

The component called schema “object of analysis”, as its name implies, specifies the type of object being analyzed in a given sequence. The component called schema “procedure of analysis”, in turn, specifies the procedures of description used for identifying, explaining, classifying, etc. the object of the analysis. The two components form “micro”-configurations – “patterns” – that we call schemas. Thus, from a formal point of view:

– any ASW model of description is a complex configuration comprising a set of sequences belonging to one or other of the five functional types cited above;

– a sequence, in turn, is a configuration comprising two or more “micro-configurations” called schemas, at least one of which belongs to the type of schemas “Identification of the object of analysis”.

5.4. The objects of thematic analysis

The “essential purpose” of a model of description such as the one intended for analyzing music (Figures 5.1 and 5.2) is obviously to enable an analyst to identify, explain – to provide an expert assessment of – an object subjected to his own intellectual, personal or professional judgment. What then are the objects of analysis and how can we approach and process them? In a semiotic approach to the analysis and expert assessment of audiovisual corpora, we distinguish five main types of objects which, indeed, determine the distinction between the five types of sequences presented above (see section 5.3).

The first type of objects brings together all the objects belonging to the domain of knowledge/expertise documented by an audiovisual corpus making up, e.g. the audiovisual collection of a video library or archive. These objects are called referential objects.

In our case, there are all sorts of objects from the domains of expertise of the ASW fields of experimentation.6 For example, there are types of objects identified by conceptual terms such as [AUTHOR], [SCHOOL OF THOUGHT], [INTELLECTUAL WORK], [TYPE OF LITERATURE], [GENRE OF LITERATURE], [LITERARY GENRE], [LITERARY MATERIAL], [LITERARY MOTIF], [SCIENTIFIC DISCIPLINE], etc. All these types of objects (and many more) are part of the domain of expertise/knowledge covered by the Workshop of Literature from Here and Elsewhere (LHE).7

Any phrase written in capital letters and between square brackets “[ ]” denotes a concept or, as we prefer, a conceptual term, i.e. an expression which has been listed in the metalanguage of description used for analyzing and describing a given “real” object. For example [AUTHOR] is a metalinguistic term – a conceptual term (CT) – which expresses the functional notion (i.e. role) of “authorship”. Concretely speaking, it – the conceptual term [AUTHOR] – is used by the analyst for allocating the authorship of some book, to a “real” person or a collective entity (or, in our case, to a quotation from the “real” person or collective entity in the analyzed audiovisual text). Therefore, the very term [AUTHOR] takes – as we say in technical circles – a multitude of different values, if the analyst uses it to identify all people, groups, institutions, etc. which have played the role of an author in the history of French literature: Zola, Balzac, Molière, Voltaire, Stendhal, Pagnol, Mauriac, Bernanos, Proust, etc. Each of these proper nouns (names) implies a specific value of the conceptual term [AUTHOR] in such-and-such an audiovisual passage or document being analyzed.

The second type of objects which may serve to analyze an audiovisual corpus brings together all objects which enable us to (spatially, temporally etc.) locate an object belonging to the domain of knowledge/expertise. These are types of objects represented by conceptual terms such as [PHYSICAL LOCATION], [PLACE OF ACTIVITY], [COUNTRY], [GEOGRAPHICAL REGION], [COMMUNITY], etc. or even types of objects represented by terms such as [PERIOD], [ERA], [DATE], [BEGINNING], [END], etc.

This second type of objects is common to all domains of expertise/knowledge. In the concrete case of our fields of experimentation, we use them for locating excavation sites from this-or-that era, authors having contributed to a given national literature, or languages spoken in a certain region of the world. The objects belonging to this second functional type are called contextual objects.

The third type of objects encompasses all objects enabling us to analyze the different ways to deal with an object from the domain of knowledge/expertise, from a discursive or rhetorical point of view. These types of objects are represented by conceptual terms such as [GENRE OF DISCOURSE], [TYPE OF DISCOURSE], [DISCURSIVE THEMATIZATION], [DISCURSIVE POINT OF VIEW], [DISCURSIVE FRAMING], [DISCURSIVE FOCUS], etc. with which we are able to specify how an object or a domain of knowledge is developed by its author in an audiovisual document, or in a corpus of audiovisual texts). The objects in this third functional category are called discursive objects.

The fourth type of objects brings together all objects enabling us to analyze the visual and acoustic mise-en-scène of an object from a domain of knowledge/expertise. The main types of these objects are represented by conceptual terms such as [VISUAL FRAMING], [SOUND FRAMING], [VISUAL FOCUS], [VISUAL SHOT], [SOUND SHOT], [CAMERA MOVEMENT], [DURATION (of the shot)], etc. Using these types of object we are able to analyze, if necessary or desired, how a theme or topic is visualized (“audio-visualized”) in an audiovisual corpus. The objects belonging to this fourth functional type are called audiovisual objects.

Finally, the fifth type encompasses all objects enabling the analyst to motivate, justify, explain etc. his analysis of an object from the domain of knowledge/ expertise. There are types of objects such as [COMMENT], [JUSTIFICATION], [EXPLANATION], [TEXTUAL NOTE], etc. which help us to comment upon, justify or explain an analysis. The objects of this functional type are called reflective objects. The five functional types of objects of analysis are defined in the form of a hierarchical metalexicon of conceptual terms (a domain ontology) which constitutes an essential part of the metalinguistic resources of ASW. There is a more detailed and well-argued presentation of this metalexicon to be found in [STO 12b].

When concretely analyzing an audiovisual corpus, it is rare for a conceptual term referring to an object belonging to one of these five types to be used alone. In most cases, it is associated with other conceptual terms that form a conceptual configuration (see Figure 5.9) which represent the domain (or a part of the domain) to be analyzed or expertly assessed. Hence, put simply, the conceptual term [AUTHOR] is associated, by definition, with other conceptual terms representing objects which, like it, belong to the first functional type and/or with one or more conceptual terms representing objects belonging to the four other types of objects listed above.

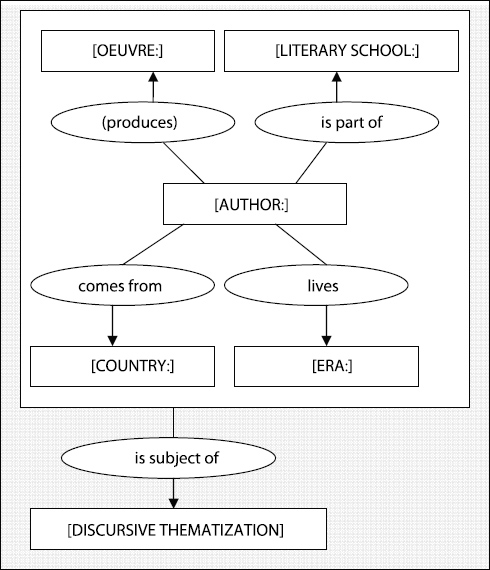

The term [AUTHOR], in one of the LHE models of description, is hence associated with [OEUVRE], [LITERARY STREAM] … – all are conceptual terms representing the first type of objects of analysis. It is also associated with conceptual terms such as [COUNTRY], [PERIOD], [ERA], [DISCURSIVE THEMATIZATION], etc. which represent objects belonging to other functional types: objects enabling us to analyze the spatial or temporal location of an author, objects to analyze how we “speak” about an author in an audiovisual document, etc.

The “association” of the conceptual terms deemed necessary (if not sufficient) to describe a certain type of themes or topics in an audiovisual corpus, forms what in the tradition of Greimas’ structural semiotics ([GRE 66; GRE 79]) is known as a configuration (here: a definitional configuration of a given type of topics, see also [STO 03]). A configuration is composed of a set of terms which are selected and – in Greimas’ words – contracted by relations, or rather, specific types of relations.

A relation can only select and contract conceptual terms which are compatible with it, and the “contraction” or linking of two or more terms imposes an orientation between the contracted terms. Finally, a configuration of terms may be “1D” but may (to borrow another of Greimas’ expressions) also manifest itself in the more complex form of a composite configuration, e.g. a configuration which encompasses another configuration.

Figure 5.9. Generic configuration of the conceptual terms defining the discursive thematization of an object of knowledge

Hence Figure 5.9 shows such a more complex configuration, which we use in order to define the discursive treatment of a topic or theme (the conceptual term [DISCURSIVE THEMATIZATION] being only one possible conceptual term among many of others we could use for describing the specificity of a topic as a result of a given processing of a concrete audiovisual text or specific passage.

Figure 5.9 also shows that the linking between selected conceptual terms necessarily introduces an orientation between the terms selected and contracted by a specific type of relation. In the example represented by Figure 5.9, we can easily see that the relation <produced>8 originates from the term [AUTHOR] and leads to the term [WORK] (to invert this orientation would have obvious semantic repercussions on the model of description); the term <subject of> leads to the conceptual term [DISCURSIVE THEMATIZATION] and originates from a whole configuration of terms (a conceptual term which, to quote Greimas and his innovative semantic approach once more, enjoys an internal capacity of condensation/expansion – condensation in a single “complex” term and expansion in a configuration which is characteristic and explicative of the complex term …). Here we must end out brief presentation of the configurations of conceptual terms, and refer the interested reader to [STO 12b] for more information.

As we saw concretely earlier (see Figures 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4), the identification and input of the values appropriate for a conceptual term or rather a configuration of conceptual terms defining a type of topic and its discursive processing and/or audiovisual mise-en-scène, is done using the interactive working forms in the ASW Description Workshop. This is a task which takes place, on the one hand, step by step, and on the other hand, using procedures of description and specialized data entry forms. “Step by step” means – as Figure 5.7 shows – that the definitional configuration, i.e. the configuration of the conceptual terms which defines a type of topic and its discursive and/or visual processing, manifests itself as a series of functionally specialized sequences which make up an interactive form. In other words, each sequence represents or takes charge of a part of the underlying definitional configuration. The use of procedures of description to analyze an audiovisual text using a definitional configuration will be discussed in section 5.5).

To conclude brief overview of the object of analysis making up a sequence of a model of thematic description, let us reiterate that the conceptual term may take the form of a generic term or an instantiated term (see Figure 5.9). In the former case, this is a general term waiting to receive the appropriate value to adequately represent an object of description; in the second, the appropriate value for representing the object of analysis has already been assigned to it.

In our concrete example of the Uyghur Muqam (Figure 5.2), the conceptual term (CT) [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC] is generic – it needs to be specified in order to correspond to the object of knowledge being studied, i.e. to the genre of world music “Muqam”. This specification is done by way of a specific procedure of description – which may either be free (the analyst inputs the value) or controlled (using a thesaurus). In our case, we use a thesaurus (see Figure 5.2).

Looking once more at Figure 5.1, we can see that the first sequence is dedicated to a first functional part of the topic entitled “Identification of the CT [DOMAIN OF KNOWLEDGE]” and a second part comprising the phrase “Culture and music” (in a yellow box). This is an instantiated term, i.e. a generic term already interpreted in regard to the audiovisual corpus being analyzed. The extreme case is here represented by models composed solely of instantiated terms – the only “manipulation” carried out by the analyst would consist of “activating” the generic part of each referential term. Conventionally, A referential term is written as follows: [GENERIC TERM: value] (see Figure 5.9).

There are several practical interests which led us to systematically use this genre of the so-called condition of referentialization. In the context of collection and analysis of a corpus in order to document domains of knowledge specified beforehand by the conceivers or interested parties in a “thematic” video-library, referentialization identifies the domain of knowledge “on behalf” of the analyst. This means that the analyst’s time investment is greatly reduced, as is the probability of indexing errors; another advantage is that at least an overall homogeneity can be maintained between the results of descriptions carried out collectively or remotely. Finally, this technique may also be used as a convenient means of classifying an audiovisual collection indexed and distributed in a thematic video library. It should also be noted that we use the condition of referentialization not only for the preliminary identification of the domains of knowledge covered by a video-library but also, if possible, for the spatial and or temporal contextualization of a topic dealt with in an audiovisual text – and this is still in the pursuit of the same goals – decreasing the analyst’s working time, facilitating his work and homogenizing the results of work performed by different analysts (by a “community of analysts”).

5.5. Procedures of analysis

A sequence from a model of thematic description, we have said, is usually composed of an “Objects of analysis” schema and a “Procedure of analysis” schema. Let us now take a brief look at the main procedures of analysis that are used to process an audiovisual corpus, identify and explicit such-and-such a topic or theme of interest to us within an audiovisual corpus.

It is important to keep in mind the distinction between the task of analysis on the one hand, and the procedure of analysis/description on the other: a task of analysis, in the framework of the approach developed by the ASW-HSS project, may be confused with the set of activities to be carried out in order to “fill in” this-or-that group of interactive forms making up the interface of the ASW Description Workshop. As Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6 of this book attempt to demonstrate, the analysis of an audiovisual corpus is divided into a number of main tasks. In particular, we shall focus on the following tasks:

– identification and segmentation of an audiovisual text;

– production of a metadescription explaining the content and objective of a concrete analysis;

– paratextual analysis of an audiovisual text as a whole or of a segment identified in the audiovisual text being analyzed;

– audiovisual analysis, which deals with the analysis of visual and sound shots at the expense of a systematic analysis of the content developed and conveyed by the audiovisual text being analyzed;

– thematic analysis, which rather gives priority to the explicitation, description, and interpretation of the audiovisual content and finally;

– pragmatic analysis, which deals with exposing and adapting the profile (the “identity”) of the audiovisual text to a given audience or use.

However, these six tasks are only one particular group among a wide range of activities which constitute work around an audiovisual material, as we shall term it. As Figure 5.10 shows, the work around such a material is characterized by the activities of production, scenario specification, editing and publishing (i.e. activities which shape and “sculpt” the material to make it conform to an objective of communication) on the one hand; and on the other hand, by activities of analysis, explanation, interpretation, etc. i.e. by par activities of expertise in audiovisual material.

In the context of the ASW-HSS project, we focused on analyzing audiovisual corpora. Nevertheless, as Chapter 10 demonstrates, the analysis may be used as an aid to publication/republication of existing audiovisual corpora, while remaining independent of the activity of publishing per se. The example in Chapter 10 illustrates how we can orient the analysis so as to create a new publication around a topic/theme already addressed in the context of many independently existing publications.

We shall now focus in particular on the task of thematic description. Description only constitutes one specific task among the many tasks dictating the expert work of the analyst.

Figure 5.10. Types of treatments and analyses of an audiovisual corpus

It is, however, undoubtedly the most complex task. Depending on the sequence, the task of describing a topic (or theme) may be opportunely differentiated into more specialized tasks of analysis. If we refer to the functional classification of the sequences, which is itself determined by the types of objects of analysis (see section 5.4) making up the domain of analysis, we retain the following recurring specialized tasks:

– the eliciting and description of an object (a situation …) from the domain of knowledge documented by an audiovisual corpus;

– the referential contextualization of the analyzed object;

– the description of the discursive treatment of the analyzed object;

– the audiovisual mise-en-scène of the analyzed object;

– the production of comment on the analysis performed.

The advantage of distinguishing between these different specialized tasks of thematic description is to be able to subsequently process and “model” them independently from one another. In addition, it becomes easier to define sequences of analysis which can easily be reused to elaborate new models of thematic description. Therefore, the differentiation of a task which is as complex as the description of a topic in more limited and more specialized tasks, boasts a theoretical interest (i.e. knowing how to break a more complex object down into more simple elements) as well as a practical interest (i.e. being able to reuse preexisting procedures of analysis (with or without some local adaptations) to describe new audiovisual corpora documenting other domains of knowledge).

Figure 5.11. Procedures of audiovisual corpus content description

Let us look again at Figures 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5; it is easy to see that the specialized tasks of analysis are supported by a smaller number of procedures of description or analysis.

Indeed, we systematically use only two basic procedures characterizing almost all specialized tasks of thematic description. These are the procedures of free description and controlled description (we shall discuss the other types of procedures of description in Figure 5.11).

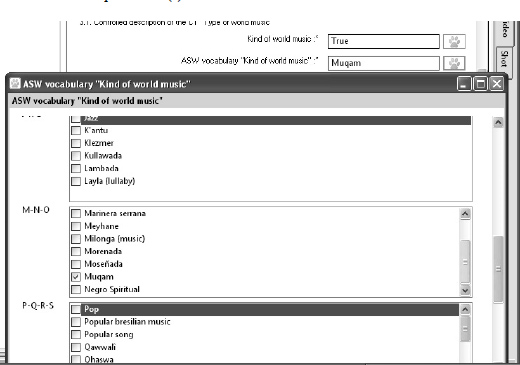

Figure 5.2 illustrates a sequence of analysis peculiar to the model of description dedicated to “Asian music”. It is the third sequence dedicated to describing a genre of world music. As shown in Figure 5.2, the analyst is first invited to produce a controlled description (see Figure 5.2, sub-sequence 3.1: “Controlled description of a genre of world music”).

As also shown in Figure 5.2, this procedure in turn comprises concrete activities of description. In our case, these are the four following activities of description:

1. Selecting the CT genre of world music. By selecting the aforementioned conceptual term, the analyst simply affirms that he is indeed processing (describing) the object of analysis represented by the conceptual term [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC]. To recap (see section 5.4), the conceptual term [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC] is part of the ASW metalinguistic resources that the “knowledge engineer” (the “concept designer”) uses to “build” models of description. The ASW metalinguistic resources are described in detail in [STO 12b].

2. Identifying, within the ASW micro-thesaurus comprising a list of natural language terms (“descriptors”) relative to the “genre of world musics”, the relevant (“descriptors”). Here, the appropriate term (the “descriptor”) is “Muqam”, which appears in the list of certified terms of the ASW micro-thesaurus. From a technical point of view, the certified expression “Muqam” forms a (or rather, in this case, the) value of the conceptual term [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC] in the domain of reference in question and which is constituted, in our example, by the audiovisual content of the recording of the interview with Sabine Trebinjac carried out as part of the ARA Program in 2007. The use of a (micro-)thesaurus forces analysts to choose (“descriptors”) from among a set of predefined terms, quite the opposite to the free input of linguistic (or visual, acoustic, etc.) expressions. Among the metalinguistic resources developed and tested as part of the ASW-HSS project, we can appreciate the importance of a thesaurus containing some 4,800 predefined terms. When compiling this thesaurus, account was taken of the three main fields of experimentation of the ASW-HSS project, i.e. CCA, LHE and ArkWork. In view of this, as explained in [STO 12b], the ASW models of description also allow access to external thesauruses. Figure 5.12 shows an extract from the micro-thesaurus “Genre of world music” developed during the ASW-HSS project, and used for describing and indexing video passages dealing with a particular genre. Let us stress that the ASW thesaurus comprises around sixty micro-thesauruses; some of these are more important than others and are very finalized and stabilized; others rather take the form of works in progress. In any case, this is a field of research which never fails to exceed the scope of a single research project, (for more information, see [STO 12b]).

3. Producing, if desirable and relevant, a circumstanced presentation (i.e. a presentation which takes account of the particular content of the audiovisual text being analyzed). This third activity offers the analyst the possibility to produce a small descriptive note intended to receive the recording.

4. Designating the referent using keywords. Here, the analyst may, if he so desires and if relevant in the context of his analysis, add keywords which are freely chosen but which are thematically limited by the object of analysis. In our example, the object of analysis is represented by the conceptual term [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC].

These four activities, in our example, constitute the procedure called controlled description. The analyst is obliged to carry out the two first activities – choosing the appropriate conceptual term(s) to represent his objects of analysis and selecting the certified expressions appearing in the thesaurus to provide the predefined values for the chosen conceptual term(s).

Figure 5.12. Use of a micro-thesaurus as part of a controlled description

Strictly speaking, the procedure of controlled description is thus reduced to the first two activities: choosing the appropriate conceptual term(s) and selecting the appropriate certified expressions from a thesaurus (or several micro-thesauruses). The third (“Producing a Presentation”) and fourth (Producing a list of keywords) activities are optional (in a double sense): first, they constitute one of the multiple contextual variants (see Figure 5.11) of the procedure of controlled description serving to enrich a thematic analysis and the appraisal of the content of an audiovisual corpus; second, even when they are present in a sequence of analysis, the analyst is not obliged to carry them out.

As we can see in Figure 5.2, these four activities are only one part of the sequence of the third description entitled “Description of a genre of world music”. To recap, this part is called Controlled description. This means that the three activities together form a specific type of procedure of description.

Similarly, the five activities of sub-sequence 3.2 – “Free description of a genre of world music” (see Figure 5.2) – fit into the type of procedures of description entitled Free description of the values of a conceptual term in a video or video segment being analyzed.

We shall take a brief look at them. The first activity making up the procedure of description is the one with which we are already familiar, i.e. the procedure Selecting the CT Genre of world music. Like the procedure of controlled description, the procedure of free description necessarily starts by the choice of the conceptual terms which represent the object(s) of analysis on which the analyst will act.

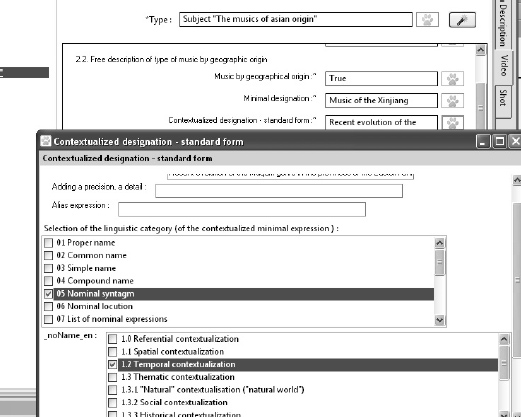

The second activity composing the procedure of free description is entitled Minimal designation – standard form. This activity is compulsory. As shown by the example in Figure 5.13, the analyst is invited to input the appropriate verbal expression to represent the selected conceptual term. In our case, we will associate the expression “Uyghur Muqam of the Xinjiang” with the conceptual term [GENRE OF WORLD MUSIC]. The analyst “freely” chooses this expression – in other words, in the analyst’s own view, the expression which is appropriate to provide information about the content developed in the audiovisual text. Other analysts might choose different expressions: perhaps a more general expression (for example, the expression “Uyghur Muqam” – an expression which eliminates the geographical location); or perhaps, on the other hand, an expression which is even more specialized (for example, the expression “Rak Muqam of the Xinjiang” – an expression which presupposes that the reader (visitor) is aware of the rak Muqam being a variant of the Uyghur Muqam …). Nonetheless, here we begin to approach one of the limits of the ASW-HSS project. These are questions regarding linguistic analysis i.e. the semantic and grammatical analysis of the linguistic expressions which are part of the corpora of “free” expressions produced by the analysts of audiovisual texts. The stakes in such work are high, given that it opens the way to linguistic engineering and its different contributions to the analysis of audiovisual content.

The other activities making up the procedure of free description of a topic are optional. However, similarly to the procedure of controlled description, they may considerably enrich the verbal data that the analyst produces. Hence, the third activity, entitled Contextualized designation – standard form (Figure 5.14), enables the analyst to further specify a minimal expression input beforehand (Figure 5.13). The contextualization of an expression consists of finding a frame for this expression and a context enabling us to better understand its meaning, its importance, its potential value for an audience, etc.

Figure 5.13. Extract from the interface of the interactive form for the minimal designation of a conceptual term or set of conceptual terms

We distinguish between two main types of contextualization: referential contextualization and enunciative contextualization. Referential contextualization is concerned with finding a complementary expression for a minimal one, the complementary expression further contextualizing the minimal expression in natural or social and/or in historical or geographical terms, etc.

Figure 5.14. Extract from the interface of the working form reserved for contextualizing the minimal designation of a conceptual term

Hence, for example, the minimal expression “Uyghur Muqam of the Xinjiang” may be favorably contextualized by complementary expressions such as “Recent evolutions of the Uyghur Muqam in the western part of the People’s Republic of China”. This contextualization is both historical and geographical, and enables a potentially interested audience to assess its own interest in the content offered in a given video or audiovisual text.

An example of possible enunciative contextualization of the expression “Uyghur Muqam of the Xinjiang” is hence translated in the following expression: “in the words of the author, S. Trebinjac, the gradual decline of the traditional Uyghur Muqam”. Thus, the enunciative contextualization offers a point of view which may help the audience to understand the meaning and potential value of a minimal expression while specifying the actor who is responsible for this point of view. As has already been mentioned, contextualization of a minimal expression is not a compulsory step in the procedure of free description but it may considerably enrich the data obtained as a result of an analysis.

The fourth activity making up the procedure of free description, in our example, is the activity enabling the analyst to produce, if he so desires, a general presentation of the object (here: the genre of world music) being analyzed.

Finally, the fifth activity also enables the analyst, if relevant and desirable, to translate an expression which was input in the original language (which is different from the language used in order to perform his analysis) into the analyst’s working language.

To conclude our brief presentation of the procedures of description, we shall reiterate the following points:

– a task of content analysis is made up of a series of more specialized tasks: a specialized task corresponding to a type of sequences composing a thematic model of description;

– any task of description is made up of one or more procedures of description;

– in particular we use two basic types of procedures of description: the procedure of controlled description and the procedure of free description; all other types of procedures (e.g. composites, with a contextual or specialized variation) are derived from these two basic types;

– any procedure of description – free, controlled or otherwise – is made up of one or more concrete activities of description;

– in any procedure of description, some activities are compulsory, others are optional;

– the addition of optional procedures to the compulsory activities creates what we call contextualized variants of the procedures of description (see Figure 5.11);

– any activity making up a procedure of description is defined in the metalexicon of conceptual terms. It constitutes one of the essential elements of the ASW metalinguistic resources which, as we already know, serve to build models of (paratextual, audiovisual, thematic, pragmatic …) description for analyzing audiovisual corpora documenting a domain of expertise.

5.6. The different components of a model of thematic description

Before more systematically introducing the central notion of library of models of thematic description, let us look once more at the main elements making up a model which is part of such a library.

Figure 5.15 gives us an insight into the elements which may be part of a thematic model of description. We shall remind ourselves that any model of thematic description is composed of one or more sequences. A sequence is specialized in the description of a specific object of analysis. Depending on the object of analysis, a sequence may belong to one or other of the five main functional types of sequences that we work with in order to analyze audiovisual corpora (this means that there are other types, but they do not play an important role in our approach).

A sequence is generally made up of two different types of schemas: the first encompasses all schemas enabling an object of analysis to be identified; the second encompasses all schemas dedicated to the use of a given specific activity making up a procedure of analysis.

We must remember that a topic, such as the one used in this chapter for example – “Music from Asia” – is rather defined by a configuration of conceptual terms than by a single conceptual term. Remember that a configuration contracts the conceptual terms representing the object of analysis that we need in order to produce a definition of a given topic.

In the case of our example relating to Uyghur music, among the conceptual terms that we need in order to define and represent the object of analysis, there are those which “frame” and represent referential objects (these are conceptual terms such as [MUSIC by GEOGRAPHICAL ORIGIN], [MUSICAL GENRE], etc.); those which “frame” and represent objects to establish the geographical and temporal location (these are conceptual terms such as [COUNTRY] or [ERA]), those which “frame” and “represent” discursive objects (these are conceptual terms such as [DISCURSIVE THEMATIZATION], [ENUNCIATIVE POINT OF VIEW] or [DISCURSIVE TOPIC]) or even, proper audiovisual objects (these are conceptual terms such as [VISUAL FRAMING], [VISUAL SHOT], [CAMERA MOVEMENT], etc.).

As shown in Figure 5.9 (representing another object of analysis), the conceptual terms form a configuration, which we suppose provides a definition, a “vision” that is sufficiently broad to be used in analyzing audiovisual corpora documenting a given topic.

Such a definitional configuration is not (normally) “projected” into a single sequence. Rather, it provides the structure of the model of thematic description as a whole. In other words, it is projected into each sequence making up a model of description: the conceptual terms representing the referential objects are projected into the sequences for describing the domain of expertise (of the model), the conceptual terms representing the localization objects are projected into the sequences for describing the referential context, the terms representing the discursive objects are projected into the sequences for describing the enunciative and discursive context of the topic, and so forth.

However, the schemas dedicated to the procedures of description are independent from the distinction between different functional types of sequences which are based – let us reiterate – on the typology of the five main types of object of analysis we use in the approach to the analysis of audiovisual corpora that we have developed. As has already been said, we currently work with two basic procedures of description (or analysis) which are free description and controlled description, and if need be, forms derived from these two procedures: composite forms relying on both these procedures in order to analyze a topic; and contextual variants of these two approaches (i.e. mainly, either more sophisticated procedures of free or controlled description; or on the contrary, procedures which are simpler than standard procedures). In any case, the two basic procedures (or, should the need arise, their derived or composite versions) form what we call “procedure of analysis” schemas. Together with the so-called “object of analysis” schemas, the “procedure of analysis” schemas thus form part of functional sequences which, in turn, are involved in models of thematic description (see Figure 5.15).

A procedure of analysis such as that of free description constitutes a conceptual configuration in itself, i.e. a definitional configuration that the analyst uses as part of his concrete work. As seen in section 5.5 a procedure of description, on the one hand, is made up of concrete activities of analysis, and on the other, is linked to an object of analysis which may be represented by a single conceptual term, a set of conceptual terms or a (part of a) configuration of conceptual terms. All these activities of analysis are defined via the ASW metalexicon of conceptual terms (therefore, via the ASW ontology) where they form a specific branch of conceptual terms, alongside another branch reserved for conceptual terms defining the five functional types of objects we work with, in keeping with the approach to analysis which is developed in this book (for more details, see [STO 12b]).

Any schema defining an object of analysis or a procedure of analysis, as shown by Figure 5.15, is a conceptual configuration characterized by conceptual terms (CT) on the one hand, and relationships between these terms on the other hand. These relationships are identified and defined by a type of specific terms called relational terms, or conceptual relations. A relational term (a conceptual relation) may represent relationships such as the spatial or temporal location, belonging to one object or another, the fact that an object accomplishes a given role towards to one or more other objects, the fact that an object acts as an input to another object, and so forth. A relational term is always defined using an original term and one or more resulting terms. This means that a relational term is oriented – the sense of a configuration depends, among other elements, of its orientation which is inherent to a conceptual relation. In addition, a relational term cannot simply contract any conceptual term – it is semantically constrained. For example, a relational term defining a spatial location must have an original conceptual term which refers to an object forming part of the “contextual” objects (which constitute a particular sub-branch of the branch of the metalexicon from which the ASW conceptual terms are derived; see [STO 12b]).

Figure 5.15. Overall view of the elements forming part of a thematic model of description

Figure 5.15 also shows the important distinction between generic terms [T] and instantiated terms [T:val]. Instantiated terms are generic terms possessing a fixed value in the context of an analysis project. Let us recall the example in Figure 5.1 where the generic term [DOMAIN OF REFERENCE] is fixed by the value “Culture and music”. The analyst cannot choose to attribute other values to the same generic term: if he envisages using a given model of description, he agrees to produce an analysis for the domain of reference (of knowledge, of expertise) entitled “Culture and music”. The instantiated terms form a group of schemas the main role of which is to set the possible values matching a model of description. For example, as part of the workshop of experimentation ArkWork, dedicated to the analysis of audiovisual corpora in archeology, we use models which set the relevant periods and places a priori. Hence in order to analyze the contributions to the archeology of Greek antiquity, the conceptual terms of referential contextualization are a priori set to values such as “Greek antiquity” (a possible value of the generic conceptual term [ERA]), “2nd Millennium BC” and “2nd Century AD” (possible values for the combination of the two generic conceptual terms [START] (or [END] and [PERIOD]).

Where do the values we use to set the empirical scope of a generic conceptual term representing a type of object, come from? As we can see in Figure 5.15, these are either outcomes of the analysis (via the procedure of free description), or “predetermined” by a list of so-called controlled terms or expressions (“descriptors”) included in a thesaurus (or a glossary, a terminology, etc.). The expressions created by the analyst to instantiate a conceptual term or a configuration of conceptual terms, may be of a verbal nature (“written” or oral), but may also be of visual or audiovisual nature (in the form, e.g. of illustrative or exemplary images or soundbites). In any case, these expressions constitute a database of semiolinguistic expressions which is shared between the analysts and is progressively enriched thanks to the contributions of the analysts working with the ASW environment and resources.

As has already been said, among the most important metalinguistic resources, we also count a thesaurus containing some 4,800 certified expressions that we have progressively set up, as the workshop of experimentation of the ASW-HSS project, is making progress. Each of these 4,800 certified expressions is an element comprising one or more facets, with each facet corresponding either to a conceptual term, or to a configuration of conceptual terms. For example, the facet “Food” corresponds to the conceptual term [FOOD] and comprises a list of certified expressions for identifying, for example, animal or plant food, dairy food, drinks, etc. A particular class of certified expressions is constituted of what we call named entities: names of people, countries, institutions, but also scientific disciplines, languages and families of languages, botanical or zoological species, and so on.

Lists composed of named entities generally serve a descriptive function of identification. In other words, a particular function of controlled description is to identify a given generic conceptual term with one or more certified expressions (of the type “named entities”). An example taken from the CCA workshop of experimentation is that of the identification of the generic conceptual term [LANGUAGE] with the language names “Aymara”, “Guarani” or “Quechua” so as to indicate by way of this operation of identification that a given passage in the video deals with one or other of these three languages.

Another function of controlled description consists of classifying a free description which was carried out beforehand and which is, as we already know, (see Figures 5.2 and 5.11), one of the two steps in composite description. First, the analyst freely describes a conceptual term or a configuration of conceptual terms; then, he suggests a classification for this description using categories which are either folksonomic (see [LED 06]), derived from a scientific classification or defined and imposed by a standard, a norm. Hence, the analyst carrying out a description of audiovisual passages dealing with the eating habits in a given ethnic group, first describes the food freely, then qualifies it – by way of the procedure of controlled description and using an appropriate micro-thesaurus constituting certified expressions, such as those belonging to a given category of food.

This very brief presentation of the organization/structure of an ASW model of description has shown us that it presents itself as a complex and multidimensional configuration made up of a set of specialized sequences, which in turn are made up of an object of description (represented by a conceptual term or a configuration of generic or instantiated conceptual terms) on the one hand, and procedures of description which enable the analyst to make the object of description explicit on the other. We have been elaborating this admittedly very structuralistic vision, since 1985, in a series of publications ([STO 85; STO 86; STO 87; STO 93a; STO 93b]) and today, we feel a certain satisfaction in being able to exemplify it concretely, in the form of an operational working environment dedicated to the analysis of the content of audiovisual corpora.

In conclusion, let us stress once more that we now have at our disposal (as we have just demonstrated) explicit procedures of definition, specification and creation of models of description on the one hand and libraries of components and parts of models (or even whole models) on the other, which are already used or reused as such or after minor modifications.

5.7. Libraries of models for the description of subjects

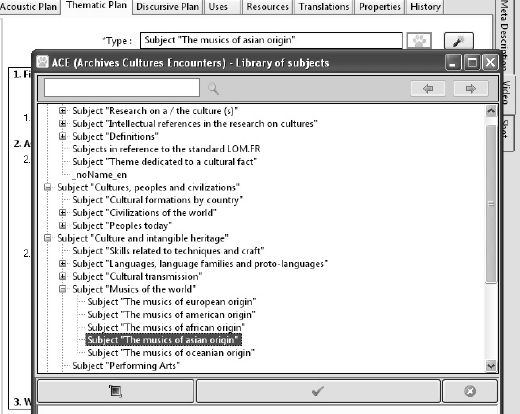

The model of description used as an example in this chapter was defined and created for a video-library dedicated to a domain of knowledge: the CCA9 video-library (which is one of the workshops of experimentation derived from the ASW-HSS project. As Figure 5.16 shows, this model of description is part of a library of models.

Figure 5.16. Extract from the catalog of models of thematic description making up the library of topics included in the CCA workshop of experimentation

This library of models of thematic description does not cover the entire audiovisual collection of the video-library in question or, a fortiori, all the myriad of potential topics addressed in this collection.

It “simply” takes account of a set of topics deemed sufficiently interesting (relevant for a given context of use …) to be developed as generic models of thematic description.

The initial hypothesis is that the audiovisual collection of a video-library (or, more generally, the textual collection of any library or digital or non-digital archive) is necessarily composed of a set of documents making up thematically recognizable “corpora”, which therefore may be limited from a referential point of view, and as regards the topics dealt with. This hypothesis does not negate the fact that an audiovisual document or text could be part of several corpora. When using the expression thematically limited corpora (audiovisual or otherwise), we must not lose sight of the fact that they could be:

– formally recognized thematic collections of audiovisual texts in a video-library (or library);

– thematic collections of closed, open or evolving texts including not only already-existing texts but also “potential” texts, i.e. texts which are still to be collected, brought together, or even created; and finally;

– thematic collections of texts which are identified and compiled either by the interested parties themselves (e.g. in our case, teachers, researchers, professionals in digitizing cultural heritage, etc.) or by experts in a given domain of knowledge, working for third parties (an audience, a stakeholder, etc.).

Nonetheless, the analysis of the content of an audiovisual corpus, as we have seen throughout this chapter, necessarily presupposes general models for describing this content, i.e. a metalanguage of description taking account of the referential specificities of the domain of knowledge or expertise to which the corpus in question refers.

It is the relative specificity of the referential objects (see section 5.4) which is at the origin of the proliferation of models of thematic description. As we have seen, it is primarily the first type of sequence in a model of thematic description, i.e. the type of sequence used for describing referential objects, that changes from one model to another. Other types of sequences that may make up a model of thematic description (referential contextualization, enunciative and discursive analysis, analysis of audiovisual expression) remain fairly stable from one model of thematic description to another. The variations in sequences being analyzed rather depend on the analyst’s expectations or requirements in terms of the level of specialization.

However, we used the phrase “relative specificity of the referential objects” above, suggesting that the transition from one domain of knowledge or expertise to another is by no means synonymous with a “radical” replacement of a set of referential objects by another set. Obviously, this is an absurd vision which takes no account of the fact that a domain of knowledge or expertise is not something predetermined or a kind of cognitive monad. A domain of knowledge or expertise is first and foremost a circumscription – a “framing” of objects conditioned by the interests, goals, knowledge, ideologies, etc … i.e. the culture of an actor responsible for this circumscription (the actor can be an individual, group, institution, etc.).

Taking the example of the workshops of experimentation which make up the ASW-HSS project, we were easily able to identify a set of referential objects found in several, or even all, the domains of knowledge or expertise which are peculiar to each of the workshops in question. For example, referential objects represented by the conceptual terms [SCIENTIFIC DISCIPLINE], [SCHOOL OF THOUGHT], [RESEARCH THEME], [THEORY], [RESEARCH ACTIVITY], [RESEARCH OBJECTIVE], etc.), are found in almost all domains of knowledge. This is simply because the audiovisual corpora documenting different domains include an important part of scientific contributions relating to research on languages and cultures (CCA domain), the history of literature and analysis of literary texts (LHE domain), archeology (ArkWork domain), Andean intangible cultural heritage (PCIA domain; see [STO 12a]) or Azerbaijani culture (PACA domain; see [STO 12a]).

Far more generally, we can say that if an audiovisual corpus documenting a given domain of expertise comprises scientific or scholarly contributions, then the conceptual terms enumerated above (and other terms which are part of the same conceptual field) may be reused – as they are, or after certain modifications – in models of thematic description dealing with this type of contribution regardless of the domain of knowledge or expertise. This is an important observation insofar as it shows that this approach may quite be easily adapted to the peculiarities of other domains of knowledge/expertise, or in the context of the analysis of thematically heterogeneous audiovisual corpora.

Looking at Figure 5.16, we can see that “within” the CCA video library, was defined and developed a series of models of description classified into a few “broad topics”. Each of these topics may, in turn, comprise a category of more specialized generic models. For example, we find a “broad topic” dedicated to the description of the videos whose content deals with languages and families of languages in the world. Another is dedicated to the description of videos about civilizations and peoples. A third is dedicated to models of description which enable us to analyze the content of videos about music in the world (the model used as an example in this chapter belongs to this group of models), and so on.