35. Page Load Events and Other Stuff

In This Chapter

• Learn about all the events that fire as your page is getting loaded

• Understand what happens behind the scenes during a page load

• Fiddle with the various

scriptelement attributes that control exactly when your code runs

An important part of working with JavaScript is ensuring that your code runs at the right time. Things aren’t always as simple as putting your code at the bottom of your page and expecting everything to work once your page has loaded. Yes, we are going to revisit some things we looked at in Chapter 10, “Where Should Your Code Live?” Every now and then, you may have to add some extra code to ensure your code doesn’t run before the page is ready. Sometimes, you may even have to put your code at the top of your page...like an animal!

There are many factors that affect what the “right time” really is to run your code, and in this chapter, we’re going to look at those factors and narrow down what you should do to a handful of guidelines.

Onward!

The Things That Happen During Page Load

Let’s start at the very beginning. You click on a link or press Enter after typing in a URL and, if the stars are aligned properly, your page loads. All of that seems pretty simple and takes up a very tiny sliver of time to complete from beginning to end:

In that short period of time between you wanting to load a page and your page loading, a lot of relevant and interesting stuff happens that you need to know more about. One example of the relevant and interesting stuff that happens is that any code specified on the page will run. When exactly the code runs depends on a combination of the following things that all come alive at some point while your page is getting loaded:

The

DOMContentLoadedeventThe

loadEventThe

asyncattribute for script elementsThe

deferattribute for script elementsThe location your scripts live in the DOM

Don’t worry if you don’t know what these things are. You’ll learn (or re-learn) what all of these things do and the effect they have when your code runs really soon. Before we get there, though, let’s take a quick detour and look at the three stages of a page load.

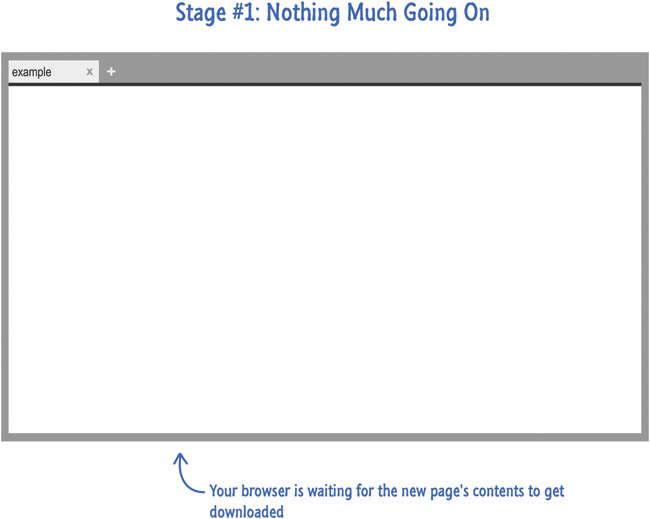

Stage Numero Uno

The first stage is when your browser is about to start loading a new page:

At this stage, there isn’t anything interesting going on. A request has been made to load a page, but nothing has been downloaded yet.

Stage Numero Dos

Things get a bit more exciting with the second stage where the raw markup and DOM of your page has been loaded and parsed:

The thing to note about this stage is that external resources like images and linked stylesheets have not been parsed. You only see the raw content specified by your page/document’s markup.

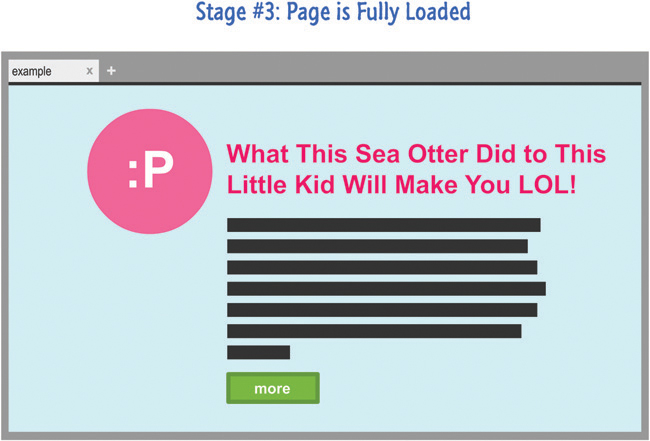

Stage Numero Three

The final stage is where your page is fully loaded with any images, stylesheets, scripts, and other external resources making their way into what you see:

This is the stage where your browser’s loading indicators stop animating, and this is also the stage you almost always find yourself in when interacting with your HTML document. That said, sometimes you’ll find yourself in an in-between state where 99% of your page has loaded with only some random thing taking forever to load. If you’ve been to one of those viral/buzz/feedy sites, you’ll totally know what I am talking about.

Now that you have a basic idea of the three stages your document goes through when loading content, let’s move forward to the more interesting stuff. Keep these three stages at the tip of your fingers (or under your hat if you are wearing one while reading this), as we’ll refer back to these stages a few times in the following sections.

The DOMContentLoaded and load Events

There are two events that represent the two important milestones while your page loads: DOMContentLoaded and load. The DOMContentLoaded event fires at the end of Stage #2 when your page’s DOM is fully parsed. The load event fires at the end of Stage #3 once your page has fully loaded. You can use these events to time when exactly you want your code to run.

The following is a snippet of these events in action:

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", theDomHasLoaded, false); window.addEventListener("load", pageFullyLoaded, false); function theDomHasLoaded(e) { // do something } function pageFullyLoaded(e) { // do something again }

You use these events just like you would any other event, but the main thing to note about these events is that you need to listen to DOMContentLoaded from the document element and load from the window element.

Now that we’ve got the boring technical details out of the way, why are these events important? Simple. If you have any code that relies on working with the DOM such as anything that uses the querySelector or querySelectorAll functions, you want to ensure your code runs only after your DOM has been fully loaded. If you try to access your DOM before it has fully loaded, you may get incomplete results or no results at all.

Here is an awesome extreme example from Kyle Murray that should help explain this:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <script> // try to analyze the book's meaning here </script> </head> <body> [INSERT ENTIRE COPY OF /WAR AND PEACE/ HERE] </body> </html>

A sure-fire way to ensure you never get into a situation where your code runs before your DOM is ready is to listen for the DOMContentLoaded event and let all of the code that relies on the DOM to run only after that event is overheard:

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", theDomHasLoaded, false); function theDomHasLoaded(e) { let headings = document.querySelectorAll("h2"); // do something with the images }

For cases where you want your code to run only after your page has fully loaded, use the load event. In my years of doing things in JavaScript, I never had too much use for the load event at the document level outside of checking the final dimensions of a loaded image or creating a crude progress bar to indicate progress. Your mileage may vary, but...I doubt it.

Scripts and Their Location in the DOM

In Chapter 8, “Variable Scope,” we looked at the various ways in which you can have scripts appear in your document. You saw that your script elements’ position in the DOM affects when they run. In this section, we are going to re-emphasize that simple truth and go a few steps further.

To review, a simple script element can be some code stuck inline somewhere:

<script> let number = Math.random() * 100; console.log("A random number is: " + number); </script>

A simple script element can also be something that references some code from an external file:

<script src="/foo/something.js"></script>

Now, here is the important detail about these elements. Your browser parses your DOM sequentially from the top to the bottom. Any script elements that are found along the way will get parsed in the order they appear in the DOM.

Below is a very simple example where you have many script elements:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <body> <h1>Example</h1> <script> console.log("inline 1"); </script> <script src="external1.js"></script> <script> console.log("inline 2"); </script> <script src="external2.js"></script> <script> console.log("inline 3"); </script> </body> </html>

It doesn’t matter if the script contains inline code or references something external. All scripts are treated the same and run in the order in which they appear in your document. Using the above example, the order in which the scripts will run is as follows: inline 1, external 1, inline 2, external 2, and inline 3.

Now, here is a really REALLY important detail to be aware of. Because your DOM gets parsed from top to bottom, your script element has access to all of the DOM elements that were already parsed. Your script has no access to any DOM elements that have not yet been parsed. Say, what?!

Let’s say you have a script element that is at the bottom of your page just above the closing body element:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <body> <h1>Example</h1> <p> Quisque faucibus, quam sollicitudin pulvinar dignissim, nunc velit sodales leo, vel vehicula odio lectus vitae mauris. Sed sed magna augue. Vestibulum tristique cursus orci, accumsan posuere nunc congue sed. Ut pretium sit amet eros non consectetur. Quisque tincidunt eleifend justo, quis molestie tellus venenatis non. Vivamus interdum urna ut augue rhoncus, eu scelerisque orci dignissim. In commodo purus id purus tempus commodo. </p> <button>Click Me</button> <script src="something.js"></script> </body> </html>

When something.js runs, it has the ability to access all of the DOM elements that appear just above it such as the h1, p, and button elements. If your script element was at the very top of your document, it wouldn’t have any knowledge of the DOM elements that appear below it:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <body> <script src="something.js"></script> <h1>Example</h1> <p> Quisque faucibus, quam sollicitudin pulvinar dignissim, nunc velit sodales leo, vel vehicula odio lectus vitae mauris. Sed sed magna augue. Vestibulum tristique cursus orci, accumsan posuere nunc congue sed. Ut pretium sit amet eros non consectetur. Quisque tincidunt eleifend justo, quis molestie tellus venenatis non. Vivamus interdum urna ut augue rhoncus, eu scelerisque orci dignissim. In commodo purus id purus tempus commodo. </p> <button>Click Me</button> </body> </html>

By putting your script element at the bottom of your page as shown earlier, the end behavior is identical to what you would get if you had code that explicitly listened to the DOMContentLoaded event. If you can guarantee that your scripts will appear toward the end of your document after your DOM elements, you can avoid following the whole DOMContentLoaded approach described in the previous section. Now, if you really want to have your script elements at the top of your DOM, ensure that all of the code that relies on the DOM runs after the DOMContentLoaded event gets fired.

Here is the thing. I’m a huge fan of putting your script elements at the bottom of your DOM. There is another reason besides easy DOM access why I recommend having your scripts live toward the bottom of the page. When a script element is being parsed, your browser stops everything else on the page from running while the code is executing. If you have a really long-running script or your external script takes its sweet time in getting downloaded, your HTML page will appear frozen. If your DOM is only partially parsed at this point, your page will also look incomplete in addition to being frozen. Unless you are Facebook, you probably want to avoid having your page look frozen for no reason.

Script Elements—Async and Defer

In the previous section, I explained how a script element’s position in the DOM determines when it runs. All of that only applies to what I call simple script elements. To be part of the non-simple world, script elements that point to external scripts can have the defer and async attributes set on them:

<script async src="myScript.js"></script> <script defer src="somethingSomethingDarkSide.js"></script>

These attributes alter when your script runs independent of where in the DOM they actually show up, so let’s look at how they end up altering your script.

async

The async attribute allows a script to run asynchronously:

<script async src="someRandomScript.js"></script>

If you recall from the previous section, if a script element is being parsed, it could block your browser from being responsive and usable. By setting the async attribute on your script element, you avoid that problem altogether. Your script will run whenever it is able to, but it won’t block the rest of your browser from doing its thing.

This casualness in running your code is pretty awesome, but you must realize that your scripts marked as async will not always run in order. You could have a case where several scripts marked as async will run in an order different from what was specified in your markup. The only guarantee you have is that your scripts marked with async will start running at some mysterious point before the load event gets fired.

defer

The defer attribute is a bit different from async:

<script defer src="someRandomScript.js"></script>

Scripts marked with defer run in the order in which they were defined, but they only get executed at the end just a few moments before the DOMContentLoaded event gets fired. Take a look at the following example:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <body> <h1>Example</h1> <script defer src="external1.js"></script> <script> console.log("inline 1"); </script> <script src="external2.js"></script> <script> console.log("inline 2"); </script> <script defer src="external3.js"></script> <script> console.log("inline 3"); </script> </body> </html>

Take a second and tell the nearest human/pet the order in which these scripts will run. It’s okay if you don’t provide them with any context. If they love you, they’ll understand.

Anyway, your scripts will execute in the following order: inline 1, external 1, inline 2, inline 3, external 3, and external 2. The external 3 and external 2 scripts are marked as defer, and that’s why they appear at the very end despite being declared in different locations in your markup.

The Absolute Minimum

In the previous sections, we looked at all sorts of factors that influence when your code will execute. The following diagram summarizes everything you saw into a series of colorful lines and rectangles:

Now, here is probably what you are looking for. When is the right time to load your JavaScript? The answer is...

Place your script references below your DOM directly above your closing

bodyelement.Unless you are creating a library that others will use, don’t complicate your code by listening to the

DOMContentLoadedorloadevents. Instead, see the previous point.Mark your scripts referencing external files with the

deferattribute.If you have code that doesn’t rely on your DOM being loaded and runs as part of teeing things off for other scripts in your document, you can place this script at the top of your page with the

asyncattribute set on it.

That’s it. I think those four steps will cover almost 90% of all your cases to ensure your code runs at the right time. For more advanced scenarios, you should definitely take a look at a third-party library like require.js, which gives you greater control over when your code will run. If you have any issues with loading things, post on https://forum.kirupa.com.

Some additional resources and examples:

Module Loading with RequireJS: http://bit.ly/kirupaRequireJS

Preloading Images: http://bit.ly/kirupaPreloadImages