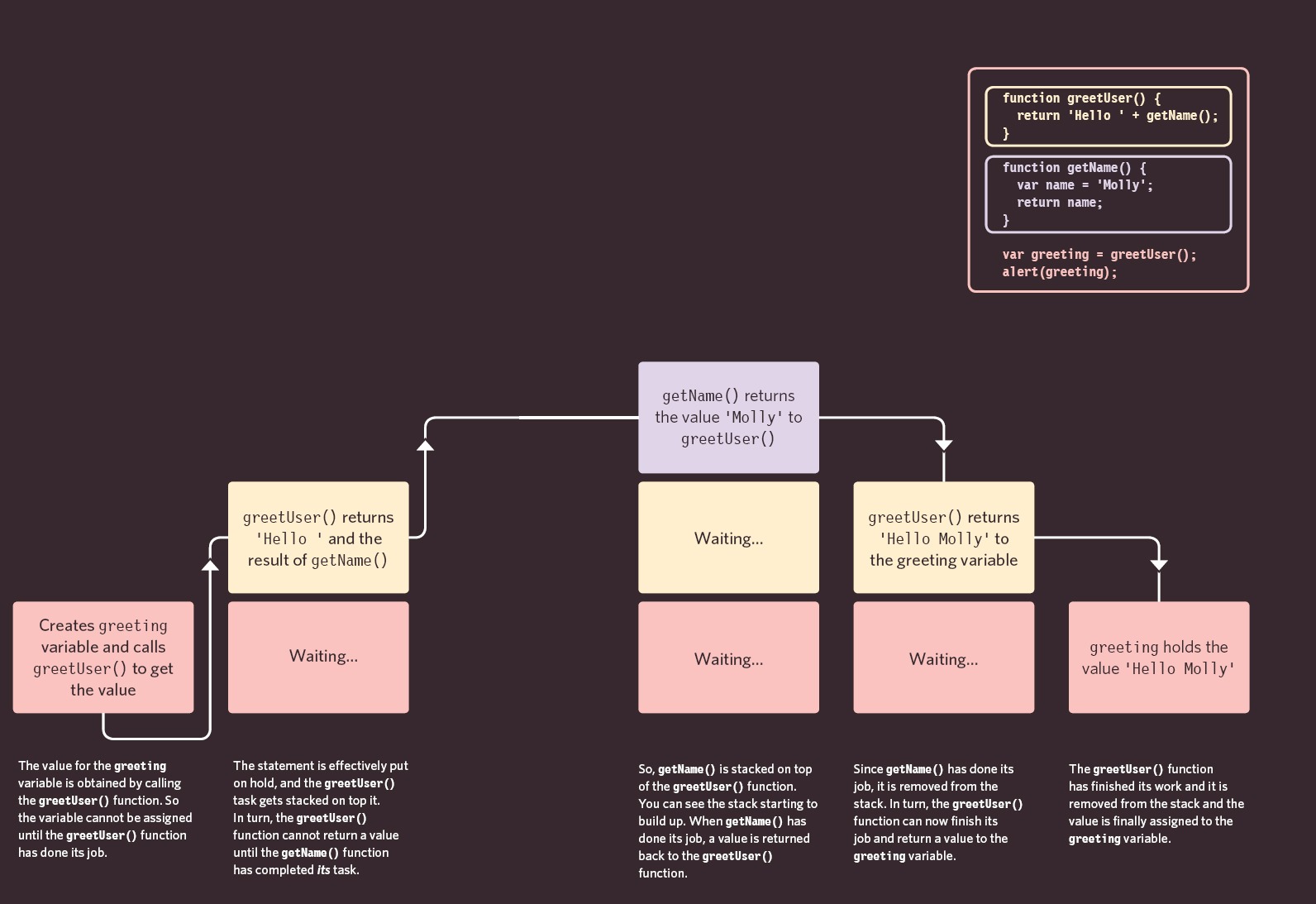

ORDER OF EXECUTION

To find the source of an error, it helps to know how scripts are processed. The order in which statements are executed can be complex; some tasks cannot complete until another statement or function has been run:

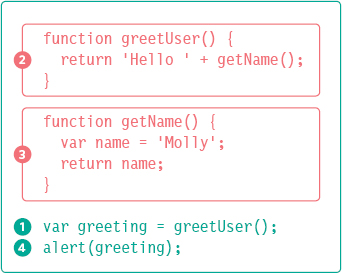

This script above creates a greeting message, then writes it to an alert box (see right-hand page). In order to create that greeting, two functions are used: greetUser() and getName().

You might think that the order of execution (the order in which statements are processed) would be as numbered: one through to four. However, it is a little more complicated.

To complete step one, the interpreter needs the results of the functions in steps two and three (because the message contains values returned by those functions). The order of execution is more like this: 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 4.

1. The greeting variable gets its value from the greetUser() function.

2. greetUser() creates the message by combining the string ‘Hello ’ with the result of getName().

3. getName() returns the name to greetUser().

2. greetUser() now knows the name, and combines it with the string. It then returns the message to the statement that called it in step 1.

1. The value of the greeting is stored in memory.

4. This greeting variable is written to an alert box.

EXECUTION CONTEXTS

The JavaScript interpreter uses the concept of execution contexts. There is one global execution context; plus, each function creates a new new execution context. They correspond to variable scope.

EXECUTION CONTEXT

Every statement in a script lives in one of three execution contexts:

![]() GLOBAL CONTEXT

GLOBAL CONTEXT

Code that is in the script, but not in a function. There is only one global context in any page.

![]() FUNCTION CONTEXT

FUNCTION CONTEXT

Code that is being run within a function. Each function has its own function context.

![]() EVAL CONTEXT (NOT SHOWN)

EVAL CONTEXT (NOT SHOWN)

Text is executed like code in an internal function called eval() (which is not covered in this book).

VARIABLE SCOPE

The first two execution contexts correspond with the notion of scope (which you met on p98):

![]() GLOBAL SCOPE

GLOBAL SCOPE

If a variable is declared outside a function, it can be used anywhere because it has global scope. If you do not use the var keyword when creating a variable, it is placed in global scope.

![]() FUNCTION-LEVEL SCOPE

FUNCTION-LEVEL SCOPE

When a variable is declared within a function, it can only be used within that function. This is because it has function-level scope.

THE STACK

The JavaScript interpreter processes one line of code at a time. When a statement needs data from another function, it stacks (or piles) the new function on top of the current task.

When a statement has to call some other code in order to do its job, the new task goes to the top of the pile of things to do.

Once the new task has been performed, the interpreter can go back to the task in hand.

Each time a new item is added to the stack, it creates a new execution context.

Variables defined in a function (or execution context) are only available in that function.

If a function gets called a second time, the variables can have different values.

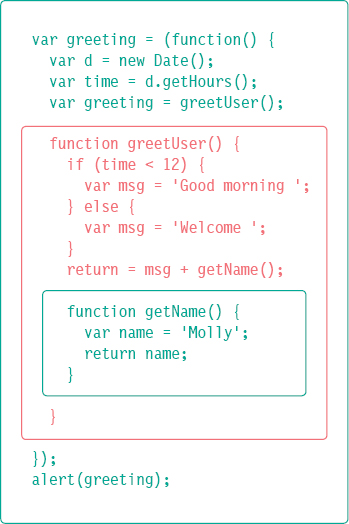

You can see how the code that you have been looking at so far in this chapter will end up with tasks being stacked up on each other in the diagram to the right.

(The code is shown at the top of the right-hand page.)

EXECUTION CONTEXT & HOISTING

Each time a script enters a new execution context, there are two phases of activity:

1: PREPARE

- The new scope is created

- Variables, functions, and arguments are created

- The value of the this keyword is determined

2: EXECUTE

- Now it can assign values to variables

- Reference functions and run their code

- Execute statements

Understanding that these two phases happen helps with understanding a concept called hoisting. You may have seen that you can:

- Call functions before they have been declared (if they were created using function declarations - not function expressions, see p96)

- Assign a value to a variable that has not yet been declared

This is because any variables and functions within each execution context are created before they are executed.

The preparation phase is often described as taking all of the variables and functions and hoisting them to the top of the execution context. Or you can think of them as having been prepared.

Each execution context also creates its own variables object. This object contains details of all of the variables, functions, and parameters for that execution context.

You may expect the following to fail, because greetUser() is called before it has been defined:

var greeting = greetUser(); function greetUser() { // Create greeting }

It works because the function and first statement are in the same execution context, so it is treated like this:

function greetUser() { // Create greeting } var greeting = greetUser();

The following would would fail because greetUser() is created within the getName() function's context:

var greeting = greetUser(); function getName() { function greetUser() { // Create greeting } // Return name with greeting }

UNDERSTANDING SCOPE

In the interpreter, each execution context has its own variables object. It holds the variables, functions, and parameters available within it. Each execution context can also access its parent's variables object.

Functions in JavaScript are said to have lexical scope. They are linked to the object they were defined within. So, for each execution context, the scope is the current execution context's variables object, plus the variables object for each parent execution context.

Imagine that each function is a nesting doll. The children can ask the parents for information in their variables. But the parents cannot get variables from their children. Each child will get the same answer from the same parent.

If a variable is not found in the variables object for the current execution context, it can look in the variables object of the parent execution context. But it is worth knowing that looking further up the stack can affect performance, so ideally you create variables inside the functions that use them.

If you look at the example on the left, the inner functions can access the outer functions and their variables. For example, the greetUser() function can access the time variable that was declared in the outer greeting() function.

Each time a function is called, it gets its own execution context and variables object.

Each time an outer function calls an inner function, the inner function can have a new variables object. But variables in the outer function remain the same.

Note: you cannot access this variables object from your code; it is something the interpreter is creating and using behind the scenes. But understanding what goes on helps you understand scope.

UNDERSTANDING ERRORS

If a JavaScript statement generates an error, then it throws an exception. At that point, the interpreter stops and looks for exception-handling code.

If you are anticipating that something in your code may cause an error, you can use a set of statements to handle the error (you meet them on p480). This is important because if the error is not handled, the script will just stop processing and the user will not know why. So exception-handling code should inform users when there is a problem.

Whenever the interpreter comes across an error, it will look for error-handling code. In the diagram below, the code has the same structure as the code you saw in the diagrams at the start of the chapter. The statement at step 1 uses the function in step 2, which in turn uses the function in step 3. Imagine that there has been an error at step 3.

When an exception is thrown, the interpreter stops and checks the current execution context for exception-handling code. So if the error occurs in the getName() function (3), the interpreter starts to look for error handling code in that function.

If an error happens in a function and the function does not have an exception handler, the interpreter goes to the line of code that called the function. In this case, the getName() function was called by greetUser(), so the interpreter looks for exception-handling code in the greetUser() function (2). If none is found, it continues to the next level, checking to see if there is code to handle the error in that execution context. It can continue until it reaches the global context, where it would have to it terminate the script, and create an Error object.

So it is going through the stack looking for error-handling code until it gets to the global context. If there is still no error handler, the script stops running and the Error object is created.

ERROR OBJECTS

Error objects can help you find where your mistakes are and browsers have tools to help you read them.

When an Error object is created, it will contain the following properties:

| PROPERTY | DESCRIPTION |

| name | Type of execution |

| message | Description |

| fileNumber | Name of the JavaScript file |

| lineNumber | Line number of error |

When there is an error, you can see all of this information in the JavaScript console / Error console of the browser.

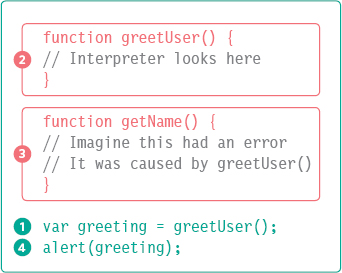

You will learn more about the console on p464, but you can see an example of the console in Chrome in the screen shot below.

There are seven types of built-in error objects in JavaScript. You'll see them on the next two pages:

| OBJECT | DESCRIPTION |

| Error | Generic error - the other errors are all based upon this error |

| SyntaxError | Syntax has not been followed |

| ReferenceError | Tried to reference a variable that is not declared/within scope |

| TypeError | An unexpected data type that cannot be coerced |

| RangeError | Numbers not in acceptable range |

| URIError | encodeURI(), decodeURI(), and similar methods used incorrectly |

| EvalError | eval() function used incorrectly |

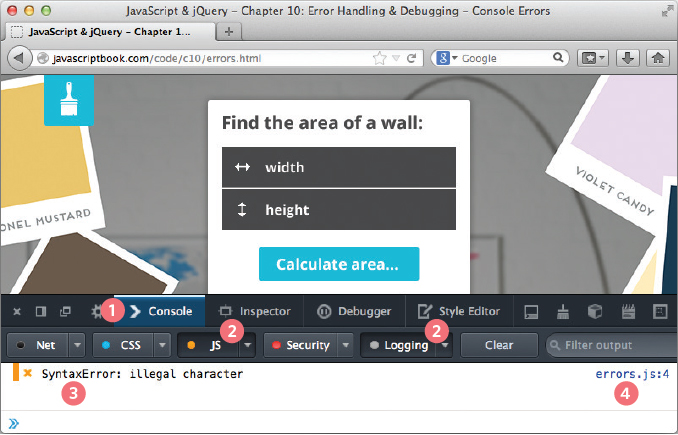

1. In the red on the left, you can see this is a SyntaxError. An unexpected character was found.

2. On the right, you can see that the error happened in a file called errors.js on line 4.

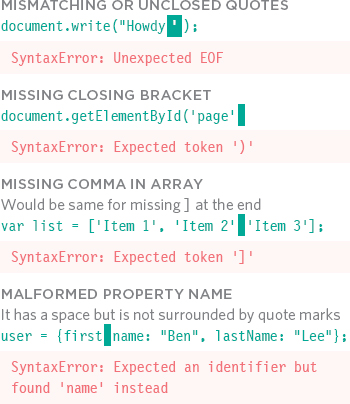

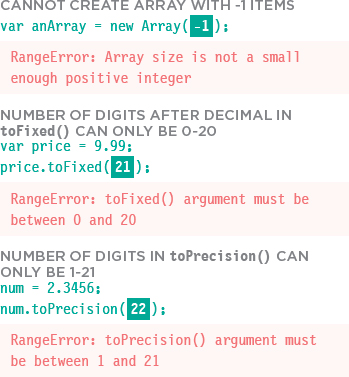

ERROR OBJECTS CONTINUED

Please note that these error messages are from the Chrome browser. Other browsers' error messages may vary.

SyntaxError

SYNTAX IS NOT CORRECT

This is caused by incorrect use of the rules of the language. It is often the result of a simple typo.

ReferenceError

VARIABLE DOES NOT EXIST

This is caused by a variable that is not declared or is out of scope.

EvalError

INCORRECT USE OF eval() FUNCTION

The eval() function evaluates text through the interpreter and runs it as code (it is not discussed in this book). It is rare that you would see this type of error, as browsers often throw other errors when they are supposed to throw an EvalError.

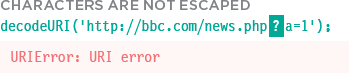

URIError

INCORRECT USE OF URI FUNCTIONS

If these characters are not escaped in URIs, they will cause an error: / ? & # : ;

These two pages show JavaScript's seven different types of error objects and some common examples of the kinds of errors you are likely to see. As you can tell, the errors shown by the browsers can be rather cryptic.

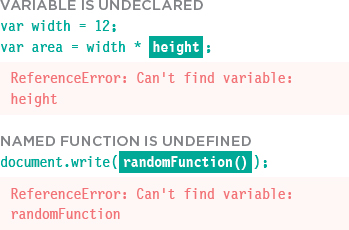

TypeError

VALUE IS UNEXPECTED DATA TYPE

This is often caused by trying to use an object or method that does not exist.

RangeError

NUMBER OUTSIDE OF RANGE

If you call a function using numbers outside of its accepted range.

Error

GENERIC ERROR OBJECT

The generic Error object is the template (or prototype) from which all other error objects are created.

NaN

NOT AN ERROR

Note: If you perform a mathematical operation using a value that is not a number, you end up with the value of NaN, not a type error.

![]()

HOW TO DEAL WITH ERRORS

Now that you know what an error is and how the browser treats them, there are two things you can do with the errors.

1: DEBUG THE SCRIPT TO FIX ERRORS

If you come across an error while writing a script (or when someone reports a bug), you will need to debug the code, track down the source of the error, and fix it.

You will find that the developer tools available in every major modern browser will help you with this task. In this chapter, you will learn about the developer tools in Chrome and Firefox. (The tools in Chrome are identical to those in Opera.)

IE and Safari also have their own tools (but there is not space to cover them all).

2: HANDLE ERRORS GRACEFULLY

You can handle errors gracefully using try, catch, throw, and finally statements.

Sometimes, an error may occur in the script for a reason beyond your control. For example, you might request data from a third party, and their server may not respond. In such cases, it is particularly important to write error-handling code.

In the latter part of the chapter, you will learn how to gracefully check whether something will work, and offer an alternative option if it fails.

A DEBUGGING WORKFLOW

Debugging is about deduction: eliminating potential causes of an error. Here is a workflow for techniques you will meet over the next 20 pages. Try to narrow down where the problem might be, then look for clues.

WHERE IS THE PROBLEM?

First, should try to can narrow down the area where the problem seems to be. In a long script, this is especially important.

1. Look at the error message, it tells you:

- The relevant script that caused the problem.

- The line number where it became a problem for the interpreter. (As you will see, the cause of the error may be earlier in a script; but this is the point at which the script could not continue.)

- The type of error (although the underlying cause of the error may be different).

2. Check how far the script is running.

Use tools to write messages to the console to tell how far your script has executed.

3. Use breakpoints where things are going wrong.

They let you pause execution and inspect the values that are stored in variables.

If you are stuck on an error, many programmers suggest that you try to describe the situation (talking out loud) to another programmer. Explain what should be happening and where the error appears to be happening. This seems to be an effective way of finding errors in all programming languages. (If nobody else is available, try describing it to yourself.)

WHAT EXACTLY IS THE PROBLEM?

Once you think that you might know the rough area in which your problem is located, you can then try to find the actual line of code that is causing the error.

1. When you have set breakpoints, you can see if the variables around them have the values you would expect them to. If not, look earlier in the script.

2. Break down / break out parts of the code to test smaller pieces of the functionality.

- Write values of variables into the console.

- Call functions from the console to check if they are returning what you would expect them to.

- Check if objects exist and have the methods / properties that you think they do.

3. Check the number of parameters for a function, or the number of items in an array.

And be prepared to repeat the whole process if the above solved one error just to uncover another…

If the problem is hard to find, it is easy to lose track of what you have and have not tested. Therefore, when you start debugging, keep notes of what you have tested and what the result was. No matter how stressful the circumstances are, if you can, stay calm and methodical, the problem will feel less overwhelming and you will solve it faster.

BROWSER DEV TOOLS & JAVASCRIPT CONSOLE

The JavaScript console will tell you when there is a problem with a script, where to look for the problem, and what kind of issue it seems to be.

These two pages show instructions for opening the console in all of the main browsers (but the rest of this chapter will focus on Chrome and Firefox).

Browser manufacturers occasionally change how to access these tools. If they are not where stated, search the browser help files for “console.”

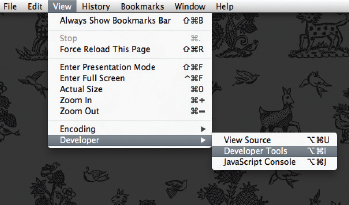

CHROME / OPERA

On a PC, press the F12 key or:

1. Go to the options menu (or three line menu icon)

2. Select Tools or More tools.

3. Select JavaScript Console or Developer Tools On a Mac press Alt + Cmd + J. Or:

4. Go to the View menu.

5. Select Developer.

6. Open the JavaScript Console or Developer Tools option and select Console.

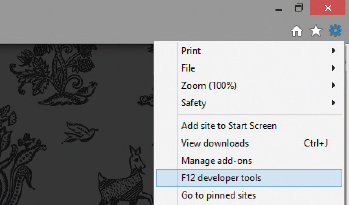

INTERNET EXPLORER

Press the F12 key or:

1. Go to the settings menu in the top-right.

2. Select developer tools.

The JavaScript console is just one of several developer tools that are found in all modern browsers.

When you are debugging errors, it can help if you look at the error in more than one browser as they can show you different error messages.

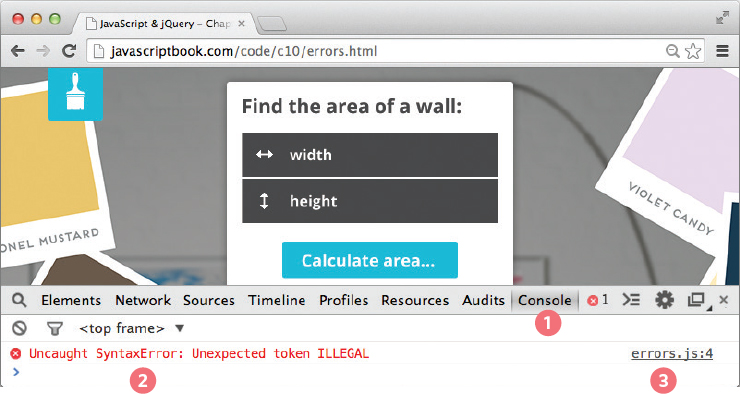

If you open the errors.html file from the sample code in your browser, and then open the console, you will see an error is displayed.

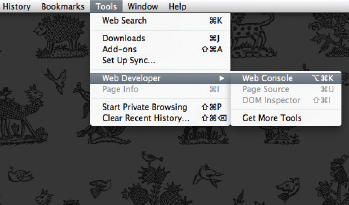

FIREFOX

On a PC, press Ctrl + Shift + K or:

1. Go to the Firefox menu.

2. Select Web Developer.

3. Open the Web Console.

On a Mac press Alt + Cmd + K. Or:

1. Go to the Tools menu.

2. Select Web Developer.

3. Open the Web Console.

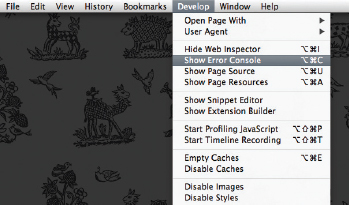

SAFARI

Press Alt + Cmd + C or:

1. Go to the Develop menu.

2. Select Show Error Console.

If the Develop menu is not shown:

1. Go to the Safari menu.

2. Select Preferences.

3. Select Advanced.

4. Check the box that says “Show Develop menu in menu bar.”

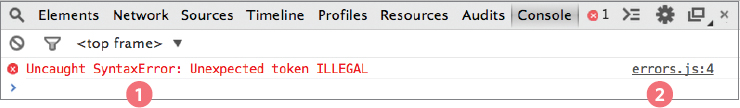

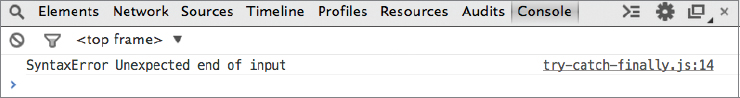

HOW TO LOOK AT ERRORS IN CHROME

The console will show you when there is an error in your JavaScript. It also displays the line where it became a problem for the interpreter.

1. The Console option is selected.

2. The type of error and the error message are shown in red.

3. The file name and the line number are shown on the right-hand side of the console.

Note that the line number does not always indicate where the error is. Rather, it is where the interpreter noticed there was a problem with the code.

If the error stops JavaScript from executing, the console will show only one error - there may be more to troubleshoot once this error is fixed.

HOW TO LOOK AT ERRORS IN FIREFOX

1. The Console option is selected.

2. Only the JavaScript and Logging options need to be turned on. The Net, CSS, and Security options show other information.

3. The type of error and the error message are shown on the left.

4. On the right-hand side of the console, you can see the name of the JavaScript file and the line number of the error.

Note that when debugging any JavaScript code that has been minified, it will be easier to understand if you expand it first.

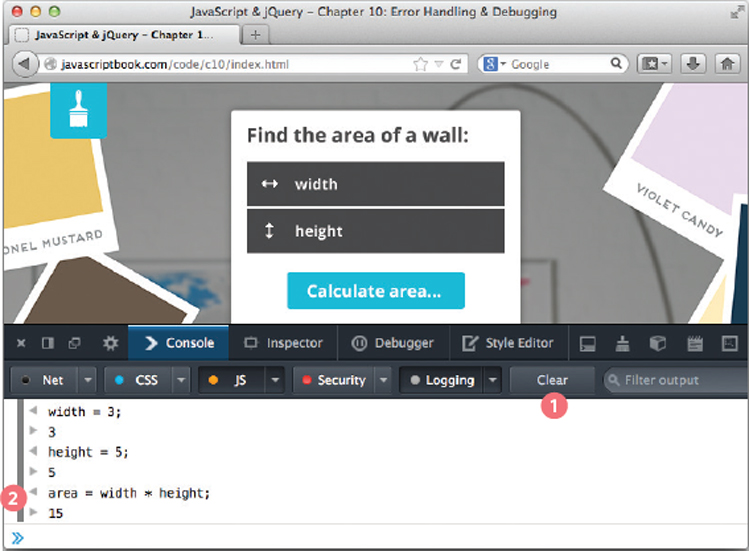

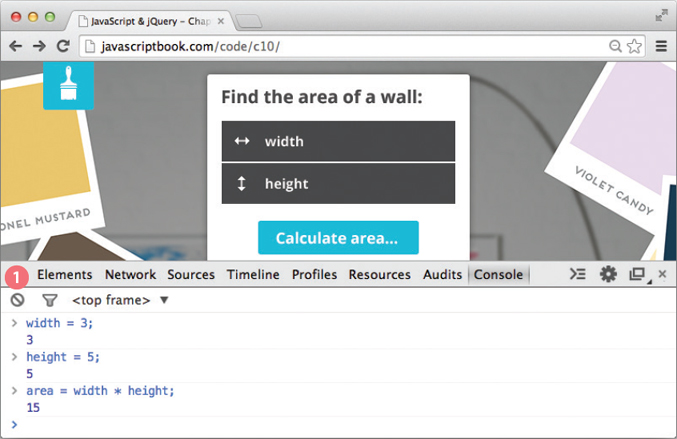

TYPING IN THE CONSOLE IN CHROME

You can also just type code into the console and it will show you a result.

Above, you can see an example of JavaScript being written straight into the console. This is a quick and handy way to test your code.

Each time you write a line, the interpreter may respond. Here, it is writing out the value of each variable that has been created.

Any variable that you create in the console will be remembered until you clear the console.

1. In Chrome, the no-entry sign is used to clear the console.

TYPING IN THE CONSOLE IN FIREFOX

1. In Firefox, the Clear button will clear the contents of the console.

This tells the interpreter that it no longer needs to remember the variables you have created.

2. The left and right arrows show which lines you have written, and which are from the interpreter.

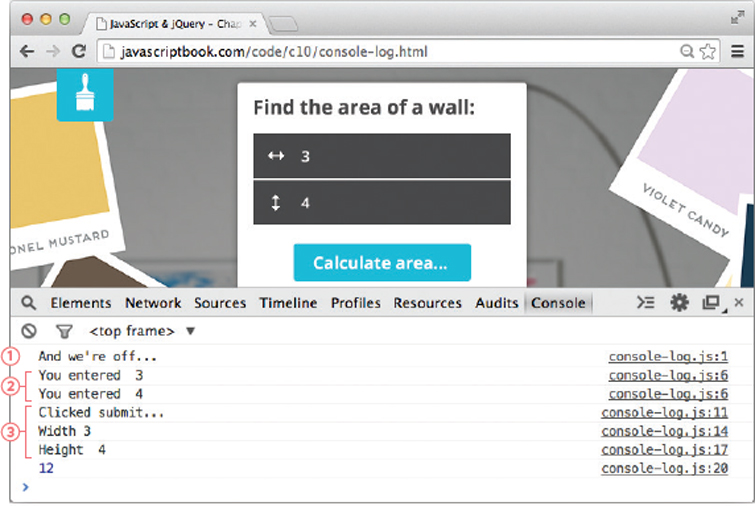

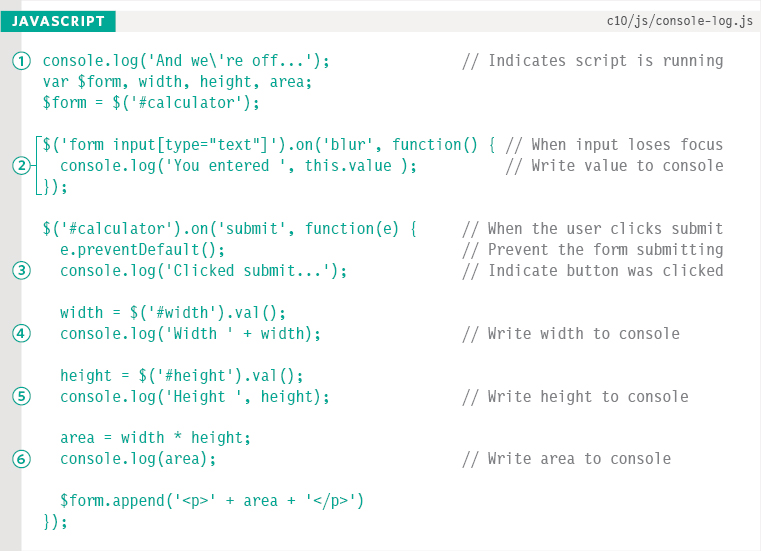

WRITING FROM THE SCRIPT TO THE CONSOLE

Browsers that have a console have a console object, which has several methods that your script can use to display data in the console. The object is documented in the Console API.

1. The console.log() method can write data from a script to the console. If you open console-log.html, you will see that a note is written to the console when the page loads.

2. Such notes can tell you how far a script has run and what values it has received. In this example, the blur event causes the value entered into a text input to be logged in the console.

3. Writing out variables lets you see what values the interpreter holds for them. In this example, the console will write out the values of each variable when the form is submitted.

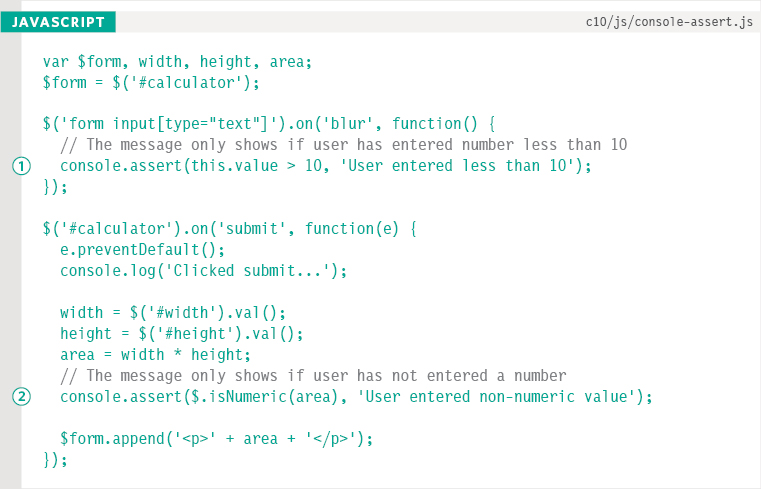

LOGGING DATA TO THE CONSOLE

This example shows several uses of the console.log() method.

1. The first line is used to indicate the script is running.

2. Next an event handler waits for the user leaving a text input, and logs the value that they entered into that form field.

When the user submits the form, four values are displayed:

3. That the user clicked submit

4. The value in the width input

5. The value in the height input

6. The value of the area variable

They help check that you are getting the values you expect.

The console.log() method can write several values to the console at the same time, each separated by a comma, as shown when displaying the height (5).

You should always remove this kind of error handling code from your script before you use it on a live site.

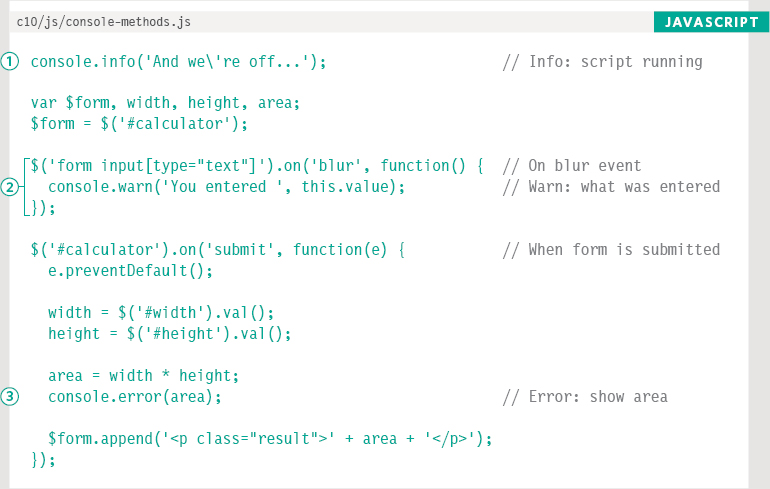

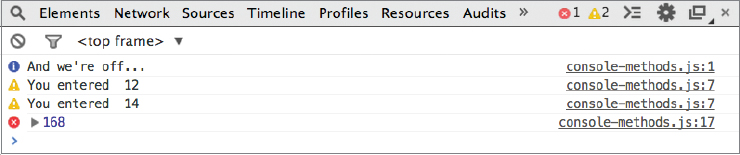

MORE CONSOLE METHODS

To differentiate between the types of messages you write to the console, you can use three different methods. They use various colors and icons to distinguish them.

1. console.info() can be used for general information

2. console.warn() can be used for warnings

3. console.error() can be used to hold errors

This technique is particularly helpful to show the nature of the information that you are writing to the screen. (In Firefox, make sure you have the logging option selected.)

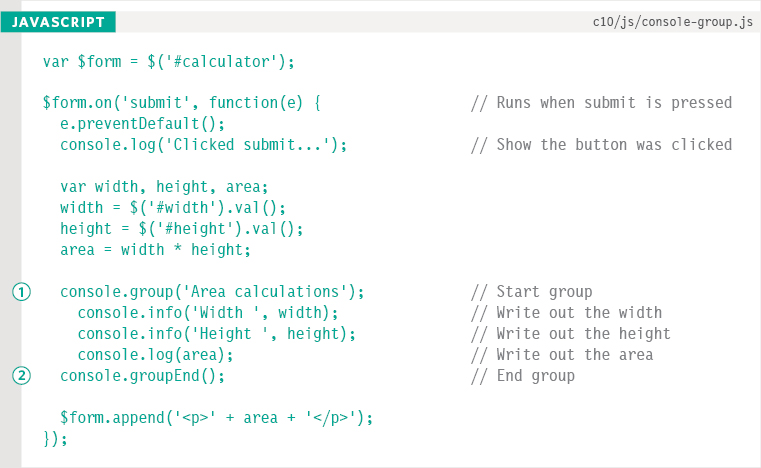

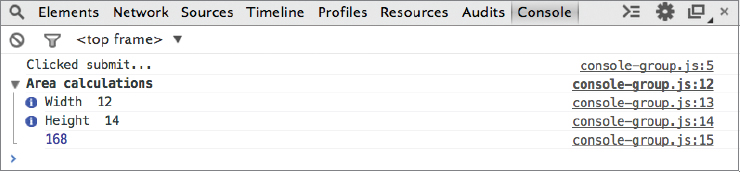

GROUPING MESSAGES

1. If you want to write a set of related data to the console, you can use the console.group() method to group the messages together. You can then expand and contract the results.

It has one parameter; the name that you want to use for the group of messages. You can then expand and collapse the contents by clicking next to the group's name as shown below.

2. When you have finished writing out the results for the group, to indicate the end of the group the console.groupEnd() method is used.

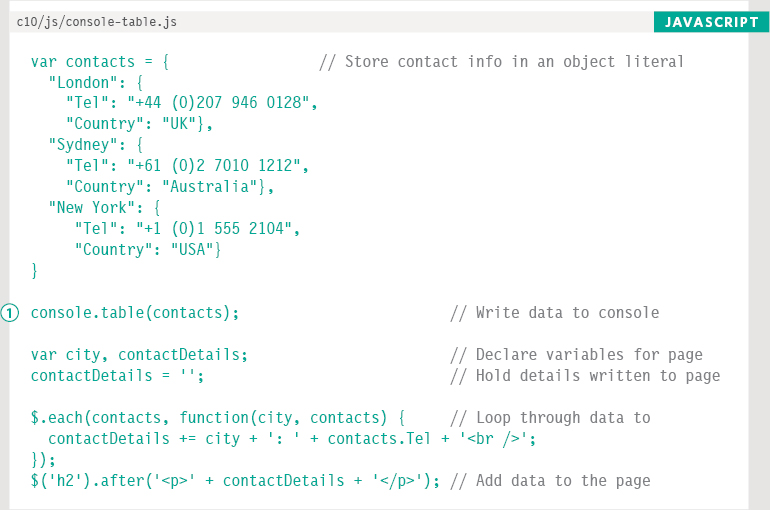

WRITING TABULAR DATA

In browsers that support it, the console.table() method lets you output a table showing:

- objects

- arrays that contain other objects or arrays

The example below shows data from the contacts object. It displays the city, telephone number, and country. It is particularly helpful when the data is coming from a third party.

The screen shot below shows the result in Chrome (it looks the same in Opera). Safari will show expanding panels. At the time of writing Firefox and IE did not support this method.

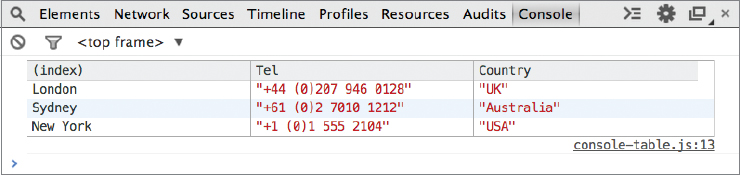

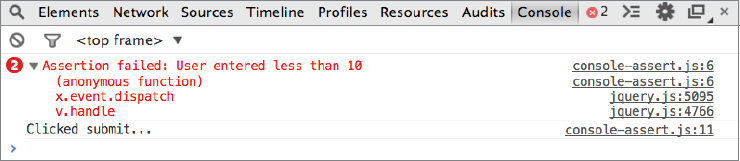

WRITING ON A CONDITION

Using the console.assert() method, you can test if a condition is met, and write to the console only if the expression evaluates to false.

1. Below, when users leave an input, the code checks to see if they entered a value that is 10 or higher. If not, it will write a message to the screen.

2. The second check looks to see if the calculated area is a numeric value. If not, then the user must have entered a value that was not a number.

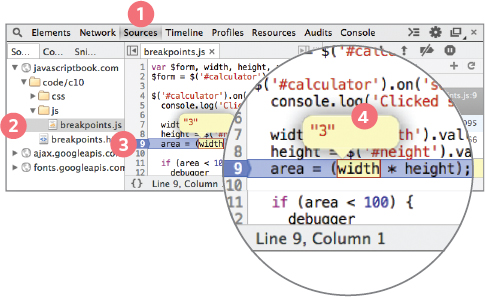

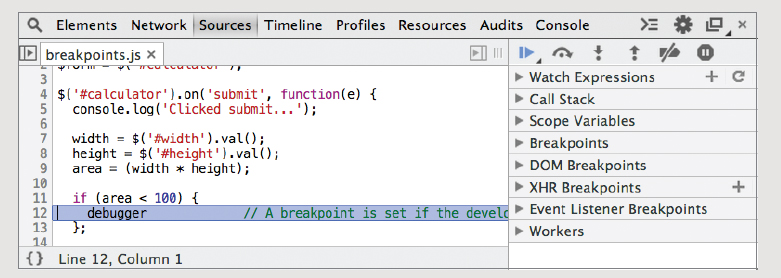

BREAKPOINTS

You can pause the execution of a script on any line using breakpoints. Then you can check the values stored in variables at that point in time.

CHROME

1. Select the Sources option.

2. Select the script you are working with from the left-hand pane. The code will appear to the right.

3. Find the line number you want to stop on and click on it.

4. When you run the script, it will stop on this line. You can now hover over any variable to see its value at that time in the script's execution.

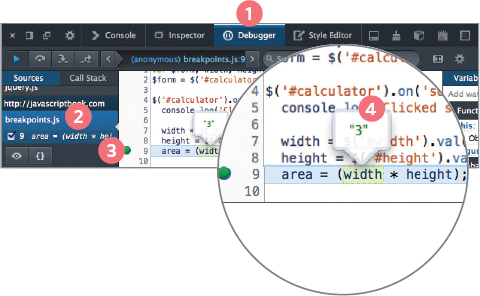

FIREFOX

1. Select the Debugger option.

2. Select the script you are working with from the left-hand pane. The code will appear to the right.

3. Find the line number you want to stop on and click on it.

4. When you run the script, it will stop on this line. You can now hover over any variable to see its value at that time in the script's execution.

STEPPING THROUGH CODE

If you set multiple breakpoints, you can step through them one-by-one to see where values change and a problem might occur.

When you have set breakpoints, you will see that the debugger lets you step through the code line by line and see the values of variables as your script progresses.

When you are doing this, if the debugger comes across a function, it will move onto the next line after the function. (It does not move to where the function is defined.) This behavior is sometimes called stepping over a function.

If you want to, it is possible to tell the debugger to step into a function to see what is happening inside the function.

Chrome and Firefox both have very similar tools for letting you step through the breakpoints.

1. A pause sign shows until the interpreter comes across a breakpoint. When the interpreter stops on a breakpoint, a play-style button is then shown. This lets you tell the interpreter to resume running the code.

2. Go to the next line of code and step through the lines one-by-one (rather than running them as fast as possible).

3. Step into a function call. The debugger will move to the first line in that function.

4. Step out of a function that you stepped into. The remainder of the function will be executed as the debugger moves to its parent function.

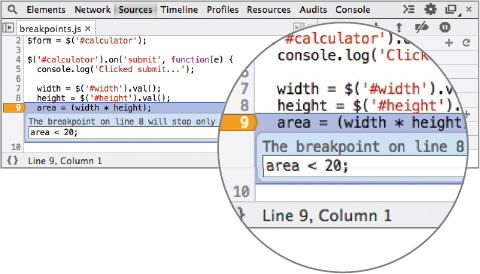

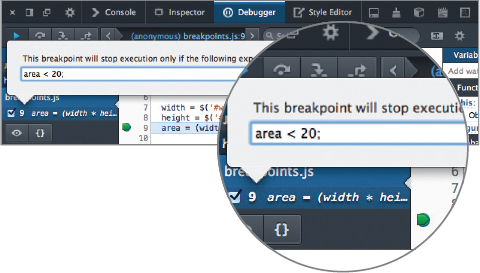

CONDITIONAL BREAKPOINTS

You can indicate that a breakpoint should be triggered only if a condition that you specify is met. The condition can use existing variables.

CHROME

1. Right-click on a line number.

2. Select Add Conditional Breakpoint…

3. Enter a condition into the popup box.

4. When you run the script, it will only stop on this line if the condition is true (e.g., if area is less than 20).

FIREFOX

1. Right-click on a line of code.

2. Select Add conditional breakpoint.

3. Enter a condition into the popup box.

4. When you run the script, it will stop on this line only if the condition is true (e.g., if area is less than 20).

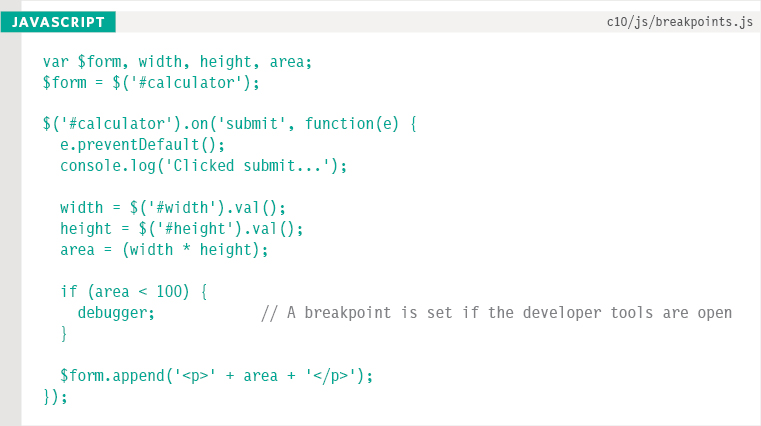

DEBUGGER KEYWORD

You can create a breakpoint in your code using just the debugger keyword. When the developer tools are open, this will automatically create a breakpoint.

You can also place the debugger keyword within a conditional statement so that it only triggers the breakpoint if the condition is met. This is demonstrated in the code below.

It is particularly important to remember to remove these statements before your code goes live as this could stop the page running if a user has developer tools open.

If you have a development server, your debugging code can be placed in conditional statements that check whether it is running on a specific server (and the debugging code only runs if it is on the specified server).

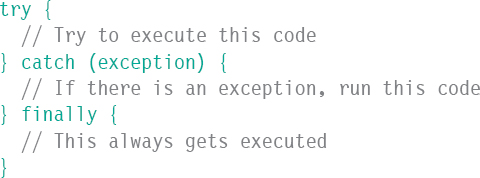

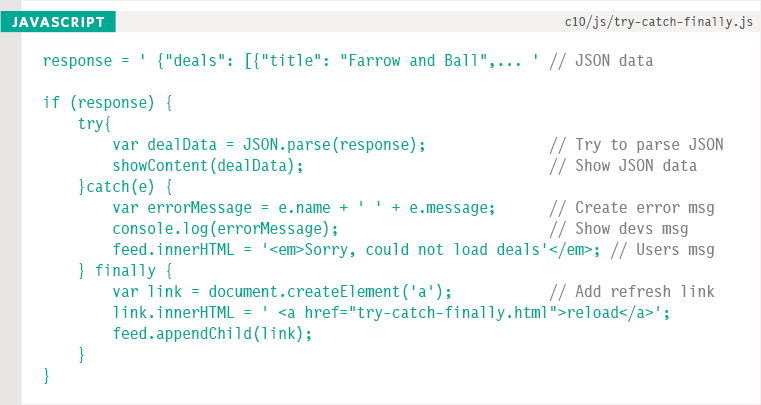

HANDLING EXCEPTIONS

If you know your code might fail, use try, catch, and finally. Each one is given its own code block.

TRY

First, you specify the code that you think might throw an exception within the try block.

If an exception occurs in this section of code, control is automatically passed to the corresponding catch block.

The try clause must be used in this type of error handling code, and it should always have either a catch, finally, or both.

If you use a continue, break, or return keyword inside a try, it will go to the finally option.

CATCH

If the try code block throws an exception, catch steps in with an alternative set of code.

It has one parameter: the error object. Although it is optional, you are not handling the error if you do not catch an error.

The ability to catch an error can be very helpful if there is an issue on a live website.

It lets you tell users that something has gone wrong (rather than not informing them why the site stopped working).

FINALLY

The contents of the finally code block will run either way - whether the try block succeeded or failed.

It even runs if a return keyword is used in the try or catch block. It is sometimes used to clean up after the previous two clauses.

These methods are similar to the .done(), .fail(), and .always() methods in jQuery.

You can nest checks inside each other (place another try inside a catch), but be aware that it can affect performance of a script.

TRY, CATCH, FINALLY

This example displays JSON data to the user. But, imagine that the data is coming from a third party and there have been occasional problems with it that could cause the page to fail.

This script checks if the JSON can be parsed using a try block before trying to display the information to the users.

If the try statement throws an error (because the data cannot be parsed), the code in the catch code block will be run, and the error will not prevent the rest of the script from being executed.

The catch statement creates a message using the name and message properties of the Error object.

The error will be logged to the console, and a friendly message will be shown to the users of the site. You could also send the error message to the server using Ajax so that it could be recorded. Either way, the finally statement adds a link that allows users to refresh the data they are seeing.

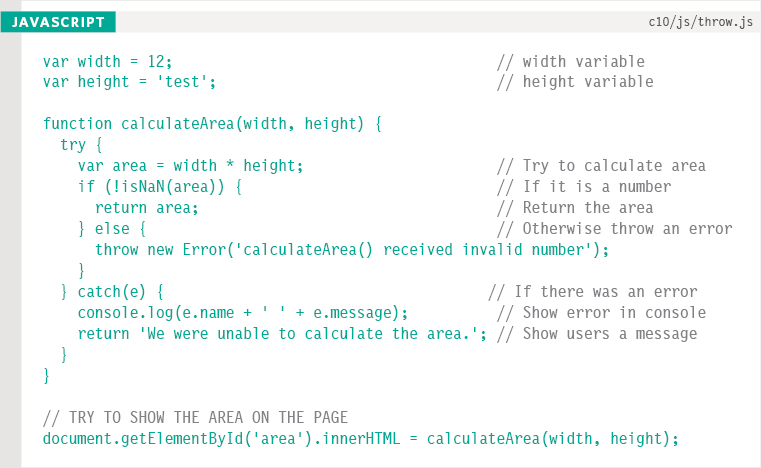

THROWING ERRORS

If you know something might cause a problem for your script, you can generate your own errors before the interpreter creates them.

To create your own error, you use the following line:

![]()

Being able to throw an error at the time you know there might be a problem can be better than letting that data cause errors further into the script.

If you are working with data from a third party, you may come across problems such as:

- JSON that contains a formatting error

- Numeric data that occasionally has a non-numeric value

- An error from a remote server

- A set of information with one missing value

Bad data might not cause an error in the script straight away, but it could cause a problem later on. In such cases, it helps to report the problem straight away. It can be much harder to find the source of the problem if the data causes an error in a different part of the script.

This creates a new Error object (using the default Error object). The parameter is the message you want associated with the error. This message should be as descriptive as possible.

For example, if a user enters a string when you expect a number, it might not throw an error immediately.

However, if you know that the application will try to use that value in a mathematical operation at some point in the future, you know that it will cause a problem later on.

If you add a number to a string, it will result in a string. If you use a string in any other mathematical calculations, the result would be NaN. In itself, NaN is not an error; it is a value that is not a number.

Therefore, if you throw an error when the user enters a value you cannot use, it prevents issues at some other point in the code. You can create an error that explains the problem, before the user gets further into the script.

THROW ERROR FOR NaN

If you try to use a string in a mathematical operation (other than in addition), you do not get an error, you get a special value called NaN (not a number).

In this example, a try block attempts to calculate the area of a rectangle. If it is given numbers to work with, the code will run. If it does not get numbers, a custom error is thrown and the catch block displays the error.

By checking that the results are numeric, the script can fail at a specific point and you can provide a detailed error about what caused the problem (rather than letting it cause a problem later in the script).

There are two different errors shown: one in the browser window for the users and another in the console for the developers.

This not only catches an error that would not have been thrown otherwise, but it also provides a more descriptive explanation of what caused the error.

Ideally, form validation, which you learn about in Chapter 13, would solve this kind of issue. It is more likely to occur when data comes from a third party.

DEBUGGING TIPS

Here are a selection of practical tips that you can try to use when debugging your scripts.

ANOTHER BROWSER

Some problems are browser-specific. Try the code in another browser to see which ones are causing a problem.

ADD NUMBERS

Write numbers to the console so you can see which the items get logged. It shows how far your code runs before errors stop it.

STRIP IT BACK

Remove parts of code, and strip it down to the minimum you need. You can do this either by removing the code altogether, or by just commenting it out using multi-line comments:

/* Anything between these characters is a comment */

EXPLAINING THE CODE

Programmers often report finding a solution to a problem while explaining the code to someone else.

SEARCH

Stack Overflow is a Q+A site for programmers.

Or use a traditional search engine such as Google, Bing, or DuckDuckGo.

CODE PLAYGROUNDS

If you want to ask about problematic code on a forum, in addition to pasting the code into a post, you could add it to a code playground site (such as JSBin.com, JSFiddle.com, or Dabblet.com)and then post a link to it from the forum.

(Other popular playgrounds include CSSDeck.com and CodePen.com - but these sites place more emphasis on show and tell.)

VALIDATION TOOLS

There are a number of online validation tools that can help you try to find errors in your code:

JAVASCRIPT

http://www.jslint.com

http://www.jshint.com

JSON

JQUERY

There is a jQuery debugger plugin available for Chrome which can be found in the Chrome web store.

COMMON ERRORS

Here is a list of common errors you might find with your scripts.

GO BACK TO BASICS

JavaScript is case sensitive so check your capitalization.

If you did not use var to declare the variable, it will be a global variable, and its value could be overwritten elsewhere (either in your script or by another script that is included in the page).

If you cannot access a variable's value, check if it is out of scope, e.g., declared within a function that you are not within.

Do not use reserved words or dashes in variable names.

Check that your single / double quotes match properly.

Check that you have escaped quotes in variable values.

Check in the HTML that values of your id attributes are unique.

MISSED / EXTRA CHARACTERS

Every statement should end in a semicolon.

Check that there are no missing closing braces } or parentheses ).

Check that there are no commas inside a ,} or ,) by accident.

Always use parentheses to surround a condition that you are testing.

Check the script is not missing a parameter when calling a function.

undefined is not the same as null: null is for objects, undefined is for properties, methods, or variables.

Check that your script has loaded (especially CDN files).

Look for conflicts between different script files.

DATA TYPE ISSUES

Using = rather than == will assign a value to a variable, not check that the values match.

If you are checking whether values match, try to use strict comparison to check datatypes at the same time. (Use === rather than ==.)

Inside a switch statement, the values are not loosely typed (so their type will not be coerced).

Once there is a match in a switch statement, all expressions will be executed until the next break or return statement is executed.

The replace() method only replaces the first match. If you want to replace all occurrences, use the global flag.

If you are using the parseInt() method, you might need to pass a radix (the number of unique digits including zero used to represent the number).

SUMMARY

- If you understand execution contexts (which have two stages) and stacks, you are more likely to find the error in your code.

- Debugging is the process of finding errors. It involves a process of deduction.

- The console helps narrow down the area in which the error is located, so you can try to find the exact error.

- JavaScript has 7 different types of errors. Each creates its own error object, which can tell you its line number and gives a description of the error.

- If you know that you may get an error, you can handle it gracefully using the try, catch, finally statements. Use them to give your users helpful feedback.