CHAPTER

9

PROMOTE PRODUCTIVE TEAM FIGHTS ON THE VITAL FEW PRIORITIES

Building a strong team is one of the most important actions a leader can take to surface and manage blindspots. In many respects, the leader creates the team and the team then creates the leader—as a primary source of feedback and advice, it becomes a key influence on the leader's thinking and behavior. When well designed, teams maximize a leader's strengths while surfacing and counterbalancing his or her vulnerabilities. The best teams have the skill and confidence needed to challenge a leader when he or she is viewing a situation in an inaccurate or incomplete manner. Often, there are team members who have worked with a leader for a number of years and understand how he or she thinks and makes decisions. The savviest among them know how to address controversial issues in a manner that gets the leader's attention. This is one reason why leaders in new roles often bring in people with whom they have worked in the past. They know and trust these individuals, not only in regard to their capabilities but also, at a deeper level, as sources of ongoing feedback and advice.

Steve Jobs inherited a superior leadership team when he bought the computer division of Lucasfilm. That group formed the nucleus of what became Pixar Animation Studios. Jobs respected the talent and drive of the group's leaders, particularly Ed Catmull and John Lasseter. They, in turn, believed in Jobs and admired his ability to think in visionary terms about Pixar. He supported them for years, both financially and emotionally, as Pixar developed new approaches that would revolutionize the making of animated films. Catmull and Lasseter challenged Jobs when necessary to prevent him from making poor decisions and, more generally, worked with him in a manner that tempered the negative aspects of his leadership style. He did the same with them, and the three of them created a company that produced one blockbuster after another, including films such as Toy Story and Finding Nemo.

The leader creates the team and the team then creates the leader—as a primary source of feedback and advice, it becomes a key influence on the leader's thinking and behavior.

Jobs came to believe that the role of a great team was to build something collectively that was greater than its individual parts—doing so by counterbalancing the negative tendencies found in every team member. As someone who loved music, Jobs used the Beatles to illustrate his point. He suggested that the quality of music created by the group was superior to what any of the band members produced as solo artists. This occurred because the interactions among the members prevented each musician's weakness, and excesses, from becoming too pronounced.1 Jobs believed Pixar's phenomenal success was due to the same type of chemistry among the firm's top leaders. When he returned to Apple, he worked hard to replicate what he had experienced at Pixar, selecting extremely talented people to be on his team and then developing a close working partnership with them.

You need a team that keeps you honest—helping you recognize your own blindspots. Consider the case of a leader I will call Justin (not his real name). The head of a small, fast-growing pharmaceutical company, he was a brilliant strategist with a reputation for using aggressive marketing campaigns to drive growth. His firm's marketing staff were pushing to promote a new product and wanted a profile (description of the product's efficacy) that would support optimistic revenue projections. The firm's R&D leader, however, was concerned that the product would have problems due to what he believed were significant side effects. He suggested a more limited approach to labeling and promoting the product. In a key leadership team meeting, the R&D leader voiced his concerns but soon retreated in the face of challenging questions from the firm's marketing leader. By the end of the meeting, the R&D leader was silent—unwilling to challenge what he believed Justin wanted. He concluded that Justin would find fault, and ultimately reject, almost any argument that resulted in a lower revenue forecast. The R&D leader didn't have the credibility or skill needed to protect Justin from himself. The product was launched but failed to sustain its initial momentum due to the adverse product side effects that the R&D leader had feared.

Some team members seek to avoid conflict, particularly when they are in group meetings. They will resist taking a position if it is contrary to the position held by those with more power than themselves. An example involves a leader I will call Irv, who had decades of experience working in a finance group for a global telecommunications firm. In one of the team's monthly meetings, a review of the firm's overall performance indicated that one business unit was below target for the year and trending downward. The leader of that business unit provided an explanation of the shortfall and gave assurances that the gap would be addressed over the next few months. Irv didn't believe that would be the case, and he wanted the CEO to be tougher on the business unit leader in the meeting. In particular, he wanted the team to discuss the details of why the business unit was performing below expectations and the specifics of needed corrective actions. The CEO had a history of not dealing with performance issues, particularly in group meetings. Irv believed it was important to be open in the group about performance shortcomings, and he thought the team could provide helpful input on what was needed moving forward. He also knew that some team members believed the CEO was failing to hold poor performers accountable, which was creating issues with those business unit leaders who felt they were being asked to perform while others were being given a pass. The CEO believed he was holding people accountable and was unaware that others viewed him in this manner. Despite what he knew and his concerns, Irv said nothing in the meeting because he didn't want to appear to be pushing the CEO to be more aggressive. He also didn't want to go up against the business unit leader in the meeting, noting afterward, “I would damage my relationship with him if I questioned him in the meeting about his group's performance. He is very defensive and sees me as an ally—it is a relationship that I don't want to jeopardize.” Irv believed that the business unit leader was a rising star in the company even though his unit was facing some short-term problems: “He may be my boss one day, and I am not going to challenge him in front of others. People have long memories, and you don't want to embarrass them or risk being on the wrong side of that type of argument. I have seen cases where people remembered these slights for years.”

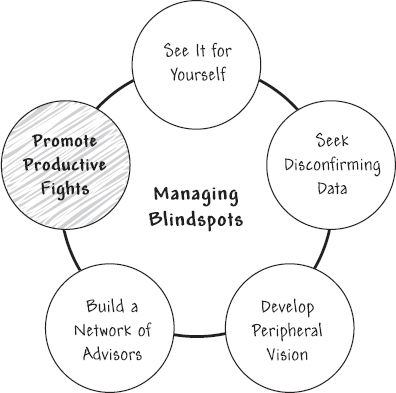

A leader who seeks to create a leadership team that can surface and address blindspots needs to take action in the following areas:

- Hire a group of smart, diverse, and passionate people.

- Focus the team on the vital few priorities.

- Embrace high-level conflicts; shun low-level conflicts.

- Establish ground rules for having productive fights.

- Ensure one voice when it comes to execution.

HIRE A GROUP OF SMART, DIVERSE, AND PASSIONATE PEOPLE

The former CEO of Coca-Cola, Roberto C. Goizueta, said that he wanted a team with many different accents around the table. This desire underscores the importance of having a team with a deep understanding of global differences. In addition, “a team with many different accents” is a metaphor for a diverse team with varied backgrounds and the benefits such a group brings with it. A common blindspot, however, is that some leaders believe their leadership teams are more diverse than is actually the case. Leaders often hire people who are like themselves, with similar backgrounds, similar decision-making styles, and even similar temperaments. This makes it easier for the leaders to understand and work with them. The downside is that they can also share the leaders’ blindspots. A leader who has grown up in an industry dominated by US firms may have difficulty appreciating the potential strength of emerging competitors from other regions of the world. If this leader's team comprises only those with similar backgrounds, the leader's blindspot in underestimating the potential threat of non-US competitors will most likely be overlooked.

The former CEO of Coca-Cola wanted a team with many different accents around the table.

In staffing a team, the leader will want to look at the total portfolio of talent in his or her group and not simply the strengths of each individual in relation to the role he or she fills. The totality of viewpoints on a team is critical when seeking to avoid the blindspots that can derail a leader. In particular, the best leaders hire those who have capabilities that the leader lacks or capabilities that balance the capabilities of others on the team. I worked with a senior leader who had only limited skill and interest in the operational details of his business. He was focused on larger strategic challenges and building external relationships that would help his firm in capturing new areas of growth. However, he understood the need to protect himself and his firm. He hired and empowered a highly capable chief operating officer who took care of the management of internal operations—freeing up the leader to focus on what he did best.

Increasing diversity also means that you want to source from different backgrounds. Many firms go back to the same sources from which to draw talent, be they target firms or particular universities. Within limits, this can be helpful, as the hiring leader has a good sense of what individuals from these companies or universities bring to the job (strengths and weaknesses). The blindspot is not seeing the weaknesses of drawing people from the same talent pool. They knew that those from their favorite universities came in with a set of tools and techniques that will serve their company well. However, the risk is that those brought in from these same sources will be too similar in how they think and behave. In particular, they often have highly correlated weaknesses. This not only results in less outside-the-box thinking but can also result in a destructive arrogance, as there is a belief there is one best approach to viewing the business or solving problems.2

You also need team members who are loyal but willing to tell you the hard truths when necessary. Logically, these traits would seem to be complementary. Loyalty, however, can easily become blind loyalty in some corporate cultures and some leaders. Surfacing blindspots is never without risks. A CEO who operates in an excessively paternalistic manner may need to hear that he is not dealing with underperformers on his team as directly as he needs to. But he may reject that input and the person who provides it. Henry Ford, as noted earlier, is a case study of this—a leader who surrounded himself with sycophants who told the great man what he wanted to hear. Those who dared to offer contrary views were ostracized by Ford or even fired. A potential trap for leaders is personally emphasizing the need for straight talk but then acting in ways that undermine this goal. The leader plays a key role in communicating how the group should handle conflict and whether or not he or she wants to hear people's thoughts even when they are contrary to what the leader believes. In some situations, a leader indicates that he or she wants to be challenged by team members but then staffs the team with individuals who are intimidated by authority. Equally common are leaders who say they want open discussion and then ignore or close down those who offer contrary views. Team members pay more attention to how a leader behaves in this area than to what he or she says is important. This is particularly evident in team meetings, where the pressure to conform can be strong. Author and researcher Gary Klein comments:

What concerns me is the tendency to marginalize people who disagree with you at meetings. There's too much intolerance for challenge. As a leader, you can say the right things—for instance, everybody should share their opinions. But people are too smart to do that, because it's risky. So when people raise an idea that doesn't make sense to you as a leader, rather than ask what's wrong with them, you should be curious about why they're taking the position. Curiosity is a counterforce for contempt when people are making unpopular statements.3

A more subtle form of a leader's words not matching his or her actions occurs when a leader wants to appear to be participative even though he or she has already reached a decision. I worked with a leader who typically made up his mind quickly, trusting his gut in making decisions. He believed the benefits of moving fast were far preferable to overanalyzing issues, particularly when there were no new data to inform a decision. However, he also believed that he gained more buy-in from his team if he positioned issues as group decisions. In one meeting, he was reviewing with his team a potential restructuring of the organization. This decision had major repercussions for the business and even for those in the room (some of whom would have their positions significantly changed as a result of a new design). The leader knew the structural configuration he wanted but didn't want to force it on the group. In essence, he wanted them to come to the same conclusion that he had reached but view it as their own. The team spent two days reviewing structural options and striving to reach consensus. The more savvy members of the team understood the leader's motives and made suggestions intended to achieve what they believed he wanted and, to the degree possible, improve upon it (for example, “I fully support a four-business-unit configuration, but we will need a centralized business development function to pursue opportunities that cut across the new units”). The result was a team that played a game of engaging in debate when, in fact, the leader had already decided on the best course of action. Over time, this leader came to modify his decision-making approach and to be clear with the team about the topics on which he wanted true debate and even productive conflict, and about those on which he had already made up his mind and wanted the team's help in executing his decision. The team appreciated his new candor because they preferred to engage in debate only in those areas that would truly make a difference, and also were glad to save time by not debating decisions that had already been made.

There are also situations in which the leader truly wants people to be direct and works to create an open culture, but finds that some members of the team remain guarded. These individuals are indirect in expressing their views and often conceal their true feelings about an issue or decision, particularly in meetings, even if the leader wants open and honest dialogue. There are a number of reasons why they may behave this way, including the types of companies at which they have worked in the past. Some firms are highly political, and those working there learn to be indirect or even deceptive. As a result, they are reluctant to operate in a more transparent manner even when given the opportunity to do so. Film director Brad Bird goes one step further; he argues that some people are simply passive-aggressive. That is, their personalities are such that they will not express what they truly believe in team discussions. Instead, they will, in his words, “peck away” behind the scenes at what he is trying to achieve with a team. He believes that such individuals can poison efforts to create an innovative culture, where openness is essential, and he removes them from his organization.4

The challenge for leaders is to create a team culture that promotes straight talk but also sustains positive working relationships. Bill George, the former CEO of Medtronics, served as a young man in Robert McNamara's Department of Defense. His experience in this group during the Vietnam War made him watchful over the rest of his career for the tendency of people to sugarcoat information that goes up the chain of authority. He found that getting people to be candid was a challenge, as many preferred to avoid conflict, particularly in a public setting. George worked hard in the firms he led to create a culture that encouraged what he called constructive conflict.5 However, a culture of open and direct communication can, however, be taken by some team members to mean that they can simply disregard the needs of others. These individuals get things done but create collateral damage that makes it more difficult for people to continue working together. They can be condescending (“You don't see the reality of what we are facing—let me explain it to you”), punishing (“Come back to me when you have conducted an analysis that is respectable”), or self-serving (“My group has clearly proven its ability in this area and should be given the lead on this new initiative”). They are comfortable with conflict but work in a manner that erodes the sense of community in the team. They go from disagreeing with others on specific issues to being constantly disagreeable.6

At the same time, these “difficult” people are often willing to voice a necessary contrarian view when others will not. In some cases, the team informally looks to them to raise tough issues that are important to the success of the business. Nevertheless, they can be criticized for doing so, as they are viewed by some as “not playing well with others” or “not being team players.” They can thus find themselves in a bind, because people want them to be direct, to raise the tough issues that others will not surface, but then criticize them for doing so. A leader's job is, in part, to determine the true dynamics of these situations. Are those willing to take a contrary view doing the heavy lifting for the group because others are unwilling to do so? When this is the case, the leader will need to encourage others on the team to step up and take on some of the burden of doing this work. Or are the contrarians simply difficult and acting in a manner that erodes the ability of the group to work collaboratively? In this case, the leader needs to determine whether these individuals can be coached to operate in a manner that creates less damage but still achieves the desired result.

One leader I know tests for the ability of people to read and work with others when he interviews them for leadership positions. At the end of the interview, he says to the potential hire, “I am going to talk to my wife later today about this interview. What do you think I am going to tell her?” He finds that many of the interviewees tell him what they want him to tell his wife (“You will say that this was a great interview and I will be a good fit to what your company needs”) instead of what actually happened—in particular, how the leader viewed the interview (“You will tell her that you liked my operational experience but had questions about my strategic capabilities”). How interviewees answer this question is an indication to the leader of their ability to view an interaction in terms of how another person is reacting to them, as opposed to viewing the interaction primarily in terms of what they want as an outcome.

FOCUS THE TEAM ON THE VITAL FEW PRIORITIES

Many teams spend time on detailed operational reviews of particular projects or initiatives. Team members add value in these reviews, but they often are not the discussions that need to be on the team's agenda. A study by the McKinsey consulting group found that only 35 percent of the six hundred executives they surveyed believed their teams focused on the areas that required their time and attention. A majority also indicated that their teams failed to allocate necessary time to key topics that did make it onto the team's agendas, such as strategy.7 High-performing teams, in contrast, obsess over the core work and stubbornly refuse to be distracted by peripheral concerns. Think of a team's potential work as being distributed on a bell curve. The operational challenges facing a firm occupy the bulk of the curve, the middle area. The most significant growth opportunities occupy one end of the curve, and the most significant risks occupy the other. Most teams spend their time in the middle area of the curve, solving problems that are operational or administrative. In contrast, the most important work for the team is found at the ends of the curve. The team needs to address the innovations that will drive future growth and the risks that can threaten the firm's viability. The question for each team leader is the extent to which important issues are pushing out the truly vital issues. A leadership team is one of the few groups in a company that can detach from operational or functional concerns to consider company-wide opportunities and risks. The leadership team at the accounting firm of Arthur Andersen, as is well known, failed to adequately understand the risks being taken as a result of the firm's work with Enron. The senior leadership at Andersen was blinded by the fees being generated at Enron and didn't fully comprehend the danger Andersen was facing in regard to its reputation—an error that ultimately pushed the firm into bankruptcy.

In many leadership teams, there is relatively little time spent on the ends of the curve, involving how to best manage innovation and risk. As a result, many teams spend the majority of their time debating topics and making decisions on topics that are not on the critical path. For instance, I find that strategy discussions and reviews in many leadership teams are at best sporadic and largely superficial. Strategy formulation becomes a budgeting discussion done once a year, with little more attention the rest of the year. This happens primarily because many teams are more comfortable dealing with operational challenges, which they understand and can often solve. The same is true of the limited attention paid in many leadership teams to potential risks. Instead, teams tend to gravitate to the areas of greatest comfort. Discussing risks can arouse anxiety within the group and gives some members a feeling of being less in control than they prefer.

Consider the damage done to the airline industry as a result of the 9/11 terrorist attack. Airline traffic plunged as a result of widespread fear of another attack. One line of argument is that the airlines could not have predicted such a horrendous act and thus the resulting damage to the industry could not have been prevented. One of the key factors in the 9/11 tragedy, however, was the inadequate security provided by airplanes’ cockpit doors (a problem corrected post-9/11). A more forward-thinking industry, or even a key company in the industry, could have anticipated the risks and advocated for changes in cockpit doors that would have decreased the likelihood that terrorists could take over a plane. Several incidents in aircraft in the years prior to 9/11 made it clear that cockpits were vulnerable to those who wanted to take command of a plane. The mistake was not seeing the rising risk in the environment and therefore not considering actions that could be taken to address it. My assumption is that the leadership groups in airline companies, pre-9/11, focused primarily on operational concerns such as meeting their productivity metrics and revenue targets—clearly important issues, but not so important that they should have excluded a more rigorous assessment of the potential risks facing the industry, given the world in which they were operating.

The problem of focusing on less critical issues is found in teams at all levels of an organization. For instance, I attended the annual leadership meeting of a global consumer products company. On the last day of the meeting, the members of each functional group met separately, with the intent of reviewing important business challenges and objectives for the upcoming year. The agenda for the human resources meeting included a discussion of the firm's rental car policy. A presenter reviewed the current policy and proposed changes (including the types of cars the firm's employees could lease). One of the attendees turned to me and said, “Can you believe that we are discussing the rate difference between a Taurus and a Focus? We have huge business and organizational challenges in front of us, and this is the type of agenda topic we spend time on.”

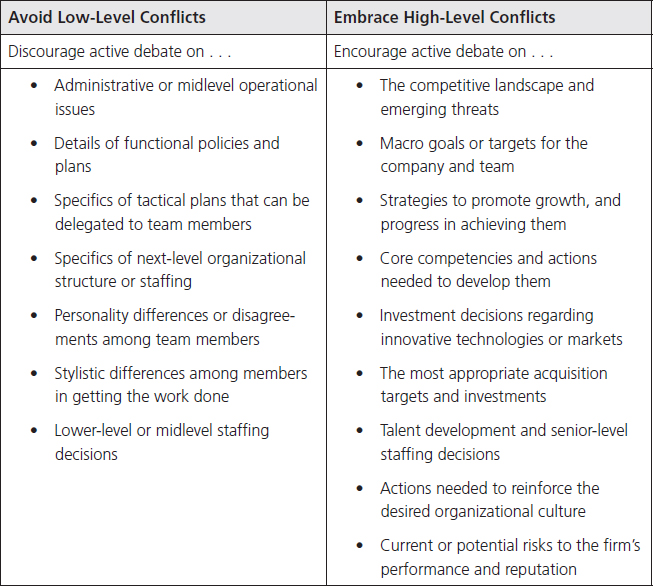

EMBRACE HIGH-LEVEL CONFLICTS, SHUN LOW-LEVEL CONFLICTS

Effective teams raise the level of “heat” in their interactions when needed in order to fully understand the complex dynamics and potential trade-offs in the decisions they are making. People in these types of groups will openly express their own points of view and challenge those with whom they disagree. In contrast, I find that many teams operate with a different goal—which is to avoid embarrassment of the team's members. Specifically, members strive to avoid embarrassing both themselves and others, particularly when dealing with contentious issues. The goal is to “save face” when interacting with others in the team setting. An unspoken agreement is made by which people understand that they will not embarrass others if others agree not to embarrass them. Instead, conflicts are addressed outside the team, often through one-on-one lobbying efforts between members or with the senior leader. While this approach is sometimes appropriate, it becomes dysfunctional when conflicts are not surfaced or openly debated in team meetings.

Not all conflict, of course, is productive. Many teams experience low-level conflict in which people fight over the less important issues, including mundane operational concerns or, in some cases, interpersonal differences. A team that engages in low-level conflicts consumes valuable time and energy in dealing with issues that are of little value compared to the more critical challenges facing the organization. Some team members grow tired of these interpersonal or emotional issues and can come to view time spent in team meetings as adding little value to the organization. Some will argue that interpersonal or emotional issues need to be resolved before higher-level conflicts are possible, but I find that many emotional issues simply distract from the larger strategic issues that need to be addressed.

Interpersonal dynamics do influence how a team operates. However, here I am underscoring the mistake of viewing interpersonal concerns as being on a par with the larger strategic debates that need to happen for a team to add real value. One reason this mistake occurs is that high-level conflicts, in most cases, are more difficult and threatening than low-level conflicts. To focus, in this case, on members of the team not getting along with other members is easier than determining the merits of investing in a risky new venture that would cripple the company if unsuccessful. I worked with one team that faced a range of threats, including government intervention to regulate its core business and the loss of market share to innovative competitors. Instead of dealing with these challenges in a robust and disciplined manner, most members of the team wanted to focus on one difficult team member whose behavior was inconsistent with the firm's espoused values (but not so extreme as to warrant removing him from the group). In essence, the firm's business model was under attack but many of its members wanted to talk about the shortcomings of one team member and how he was disrupting the team's culture. This would be an important concern if it prevented the team from addressing the strategic challenges ahead but, instead, it was an effort to solve a lower-level problem when attention was needed on much more important concerns. In general, the anxiety of dealing with the big issues results, in some leadership groups, in a focus on more manageable but less important concerns that consume the team's time. Specifically, the issue in most teams is not that people don't get along—the issue is that the larger strategic debates are not occurring with the necessary rigor.

Effective teams can raise the level of “heat” in their interactions in order to fully understand the complex dynamics and potential trade-offs in the decisions they are making.

Another common occurrence in leadership teams that influences how conflict is managed is competition for the senior job. David Nadler, a consultant to senior leaders, describes this as succession overhang.8 It creates an undercurrent in the team that makes honest dialogue very difficult. I worked with a CEO who was surprised by the political infighting among his team members, two of whom were competing for his job. The CEO assumed, incorrectly, that members of his team would act as he had done when he was in a similar position years ago as a member of the same team. He had wanted to become CEO but never put his personal ambition in front of what was best for the company. His team members, in contrast, were focused on building coalitions in the company and getting people into their respective camps. They also worked at odds to each other in an attempt to improve their own chances of winning the CEO race. The CEO's blindspot was that he didn't fully recognize how his team's behavior was damaging the company and even his reputation within the firm.

ESTABLISH GROUND RULES FOR HAVING PRODUCTIVE FIGHTS

The role of the leader is to put the right strategic issues on the table for team discussion while at the same time creating an environment that allows productive fights. This environment can be encouraged by making a group's norms about conflict explicit. An example of this is found in the early years of Xerox's research lab, a group that developed many of the innovations that drove the formation of the information technology industry. In particular, the head of the firm's R&D group, Bob Taylor, took innovative steps to promote productive conflicts among the members of his team, including the design of his team meetings: “Each participant got an hour or so to describe his work. Then he would be thrown to the mercy of the assembled court like a flank steak to pack of ravenous wolves. ‘I got them to argue with each other,’ Taylor recalled with unashamed glee…. ‘These were people who cared about their work…. If there were technical weak spots, they would almost always surface under these conditions. It was very, very healthy.’”9

This leader created an environment where the brilliant team members he had assembled would challenge each other, and him, in the most direct manner. He also understood the risks of creating such an intense environment, and sought to minimize the potential downsides of creating a team where all ideas were open to challenge and criticism.10 He wanted people to be blunt regardless of whose idea was being reviewed. However, he also wanted a line to be drawn when it came to questioning a team member's personal character or ability to contribute.

Daniel Kahneman suggests that one way to surface dissent is to get people to stake out a position before they hear what others, particularly the leader, want to do. He suggests that people get into trouble when the sources of information converge into what he calls correlated errors.11 One technique that can be used to surface divergent points of view on strategic issues is to ask each team member to take the time before a meeting to study an issue in necessary depth, summarize his or her point of view in writing, and note the pros and cons of his or her recommendation.12 In the meeting, the leader then asks each member to review his or her summary for the group, which is then discussed by the group. I worked with one group that used this approach to develop a new organizational design for the company. The process was successful in surfacing a range of options and clarifying areas of agreement among team members as well as their differences. The group then selected the two best options and worked to improve each before making a decision on which was the best choice moving forward. The end result was a hybrid that combined selected features of the two best design options.

Several general ground rules and leadership techniques are helpful in promoting productive fights among team members. As noted above, the key is to strike the right balance between confrontation and collaboration. The mix between the two varies for each company, given cultural differences, and it is the leader's job to determine how to achieve a productive balance.

- Reinforce the idea that you value constructive conflict and that you have the expectation that people should reach out to others when needed and surface key issues as needed. Establish a norm that silence on the important issues is unacceptable. Promote this norm in team meetings by asking group members for their input during a team debate (asking everyone at the table to express his or her view in turn while others listen) or simply by calling on those who have remained silent during a debate and asking for their view on the topic being discussed.

- Require the team to stay focused on the decision to be made, and encourage people to avoid personalizing the debate. In other words, you want people to be tough on ideas but not tough on each other. This can be hard to do when engaged in a passionate debate, with both the leader and some team members violating the norm. When that happens, the cooler members should be expected to intervene and put an end to behavior that will damage relationships.

- Require that people think in terms of options and seek to assess the merits of each option. Those making recommendations to the senior team should include at least two or three options with an analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of each. In addition, don't settle too quickly on one answer to a particular problem. Many teams get into trouble by not exploring alternatives in necessary detail. Some leaders promote this exploration by taking an opposing point of view on a recommendation even when they agree with that recommendation. That is, they want to challenge people to ensure that they have thought through their recommendations, including completing any necessary data analysis.

- Expect the team to surface assumptions and test to see whether data are available to validate a particular point of view. For instance, consider the team that is debating an expansion into a new and uncertain market. One member of the team is advocating a go-slow approach that some believe is too conservative. This individual believes a global recession is imminent and that his firm will need to manage capital expenditures carefully over the few years. While this may or may not be an accurate forecast, it is important to surface this assumption and be clear about the way it influences his recommendation regarding the pace of expansion.

- Expect the team to use data whenever possible but don't let seeking after precision drive out judgment calls. This is a difficult balance as some teams use too little data to inform their decisions, believing that opinions should be valued regardless of more objective data. Other teams make the opposite mistake by overanalyzing decisions or using data in a manner that discounts the collective wisdom of the group. Each leader needs to set appropriate expectations on the use of data, in general and for specific decisions that a team is addressing.

- Hold back, when necessary, on expressing your opinion in order to avoid closing down the team's consideration of various options. Often, teams will take cues from the leader, subtle or not, regarding the “right answer” and then work to obtain that answer. A leader can prevent this by remaining in a listening mode or playing a more facilitative role early on in a discussion.

- Take ownership of the process being used by the team to reach a decision. This is different from driving the team to a specific outcome, which is to be avoided. As an example, a leader may indicate that he or she will make the decision on an acquisition being considered but only after the team actively debates the merits of moving forward with the deal. The leader then describes the process that he or she wants to use to assess the proposed deal (indicating the roles various people will play and the decision-making procedures, and so forth).13

- After an active team discussion, summarize where the team stands and the next steps. Teams are often unsure about the status of an issue at the end of a meeting, particularly when the debate has been heated. In some cases, people may interpret the debate in ways that support their preferred outcomes. This doesn't mean that the leader always needs to make a decision or resolve differences, but it is helpful to summarize the state of play and the next steps in the decision-making process.

- Assess the impact of the debate on those involved and follow up as needed with those who may feel that their views were not fully taken into consideration. It is even more essential to follow up with those whose ideas were rejected, particularly in a group setting, because they can feel embarrassed or betrayed by those who confronted them. The behind-the-scenes work that needs to be done will vary by topic and individual, but it is an important part of the leader's role in ensuring that an honest debate continues to occur in the team.14

These principles for conflict should be tailored to fit the needs of your particular team in your particular company (as the cultures of companies vary). Consider a leader I will call Steve. He was president of a mid-size manufacturing firm facing competitors who were taking market share and customers. Steve, passionate in his approach, would literally turn red in meetings, pound on the table, and demand more from his team. In one meeting, he threatened to fire every one of them if they didn't stop making mistakes that were hurting the firm's performance and reputation. The louder he became, and the more threats he made, the more his team withdrew from challenging him or taking any risks that would potentially incur his wrath.

Steve eventually came to see that his style was not working with the team. He decided that he needed to be clear about what he expected and stop punishing people. He engaged the team in a general discussion on his views of how the leadership of the company needed to operate. In particular, he was explicit on the ways he wanted them to manage conflict with him and each other. The result of this discussion was a one-page summary of his expectations of the team members. For example, he noted that he wanted team members to come to the meetings with a clear point of view on issues in their areas of accountability as well as issues affecting the business in general. Other norms included keeping him informed of any emerging or current problems in their areas—he didn't want last-minute surprises. Steve stated that people should use him as a resource when problems began to emerge—and not wait until things were out of control before coming to him. He also asked people to reach out to other team members when they had team issues or concerns—rather than asking him to resolve differences among the team members (unless absolutely necessary). Steve discussed these expectations with the team and added additional points as a result of the team's input. In particular, team members noted that his punishing style made most people less likely to be open with him—a fact that he now recognized and was undermining what he wanted in the team.

Steve then took two additional actions. First, six months after the original team discussion, he assessed each team member on the degree to which that person had engaged in productive conflict with other team members (using his established expectations as indicators). He then reviewed his assessment with each person, highlighting strengths and areas for development. Second, one year after the original discussion, he determined that some members of the team simply couldn't operate in the intense team environment that he believed was necessary for his firm to be successful. He removed two members from the team and replaced them with individuals who could operate in the environment he believed was essential to the firm's success.

ENSURE ONE VOICE ON EXECUTION

Two of the most common team problems are a lack of openness in making a decision and a lack of follow-through when executing it. Richard Holbrook, an advisor to several US presidents, commented about the leadership teams he had observed over his long public career: “[You want] an open airing of views and opinions and suggestions upward, but once the policy is decided you want rigorous, disciplined implementation of it. And very often … the exact opposite happens. People sit in a room, they don't air their real differences, a false and sloppy consensus papers over those underlying differences, and they go back to their offices and continue to work at cross-purposes, even actively undermining each other.”15

In the best firms, there is active debate before a decision is reached and strong alignment once a decision is made. Being able to debate and then align is a sign of leadership team strength. Jim Collins, looking at research he did on high-performing companies, suggests that this ability “begins with having the right people—those who can debate in search of the best answers but who can set aside their disagreements and work together for the success of the enterprise.”16 Consensus is not the goal—instead, conflict is encouraged as a means of making better decisions. People on teams understand this at an intellectual level but getting them to engage in this type of behavior is challenging due to the norms in many firms that put the maintenance of relationships above the quality of decisions.

Michael Roberto, in his book Why Great Leaders Don't Take Yes for an Answer, also suggests that some teams don't engage in active debate because they are leery that discord in making a decision will cause divisions that undermine the ability of the group to execute that decision once it has been made. As a result, some team members will engage in less debate than is optimal and, instead, move quickly to a decision that all team members can support. In essence, they look for agreement faster than they should. The leader needs to be clear with the team that carrying out a debate while making decisions is not an excuse for failing to support a decision once made or failing to execute it effectively. Ann Mulcahy, former chairman and CEO of Xerox, once observed:

My own management style probably hasn't changed much in 20 years, but I learned to compensate for this by building a team that could counter some of my own weaknesses. You need internal critics: people who know what impact you're having and who have the courage to give you that feedback. I learned how to groom those critics early on, and that was really, really useful. This requires a certain comfort with confrontation, though, so it's a skill that has to be developed…. The decisions that come out of allowing people to have different views … are often harder to implement than what comes out of consensus decision making, but they're also better.17

Some teams are leery that discord in making a decision will cause divisions that will undermine the ability of the group to execute that decision once it has been made.

In some cases, team members will say that they support a decision but, particularly if it is not the outcome they preferred, fail to execute it aggressively. Or leadership team members will apparently agree to a course of action and then go back to their own teams and indicate that they don't support the outcome and suggest that their group should postpone implementing it. When this occurs, the senior leader needs to call out those who are failing to follow through, and be clear that such behavior erodes the credibility of the leadership team and will not be tolerated. Yet, in some cases, leaders allow team members to violate group-level agreements and, in particular, fail to fully execute company-wide initiatives.

Some leaders strive to avoid this outcome by working hard to reach true consensus on most decisions. The issue with this approach is that many decisions don't require consensus and the team wastes time and energy striving to achieve it. In cases where it is required (for example on a major acquisition or technology investment), a team may seek the hard version or the soft version of consensus. The hard version requires that everyone on the team agrees with the decision before moving forward. The soft version requires that team members be able to support the decision once it is made (by the team's leader or by the majority of the team). Leaders should clarify which decision rule is being used, ranging from a leader making the decision based on the team's input to a consensus decision using either the hard or the soft version of consensus. Then, after the decision is made, the leader needs to be clear about his or her expectations for implementation, including the degree of autonomy that team members will have in modifying the approach in each of their groups. In some cases, the leader will not want variation, as when cascading company-wide performance measures. In other cases, team members may be able to modify certain elements to fit their own groups (for example, they may be able to determine the specific tactics used to execute a company-wide initiative).

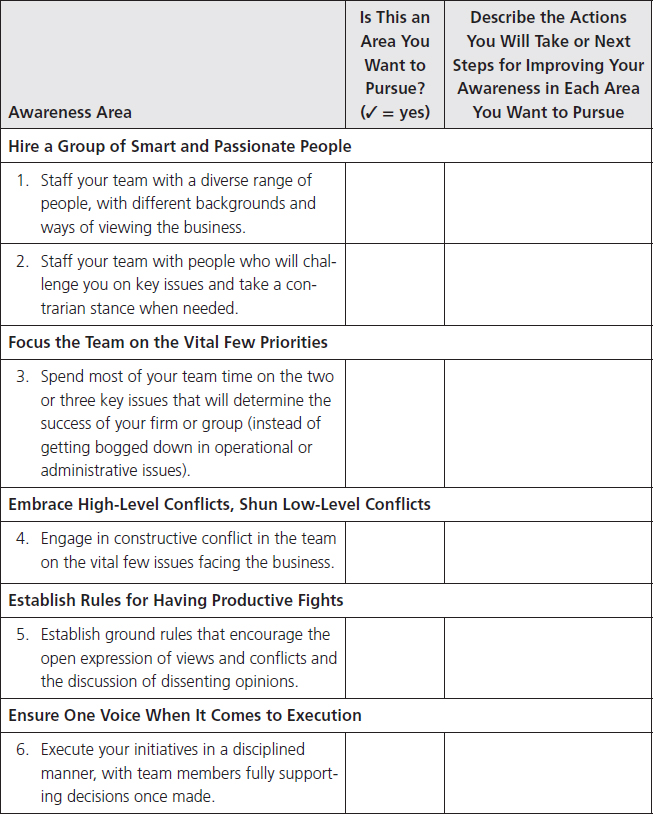

ACTIONS FOR PROMOTING PRODUCTIVE TEAM FIGHTS

The following worksheet will help you create a team environment that can constructively surface and resolve conflict.

PROMOTING PRODUCTIVE TEAM FIGHTS: SUMMARY OF ACTIONS MOVING FORWARD