Chapter 2. Where Should I Start?

It’s too easy to think we know our customers from all the meetings, phone calls, and reports we’ve read about them. To deeply understand how people actually use our products we need to go to where they work, where they play, and where they live.

—Braden Kowitz, lead designer at Google Ventures

I’m not writing it down to remember it later; I’m writing it down to remember it now.

—Slogan for Field Notes notebooks

The amount of customer development you do will depend on whether you’re attempting to validate a brand-new business idea, launch a new product to an existing customer base, or simply add or change features in an existing product.

But whether you plan on spending a few hours or a few weeks on customer development, you’ll get the most out of your time by starting with a strong foundation.

To get that foundation in place, I want you and your team to do three exercises that will take less than an hour total to complete (Figure 2-1):

Identify your assumptions

Write your problem hypothesis

Map your target customer profile

I recommend these three exercises because it’s fairly easy to get your team members to participate regardless of whether they embrace customer development or are actively skeptical. It’s hard to argue with “Let’s make sure everyone understands what we’re trying to achieve and how.”

For some of you, these exercises may feel redundant. Surely everyone on the team already knows our working assumptions and what we’re trying to achieve, right? You’d be surprised at how often that isn’t true, even for highly collaborative teams.

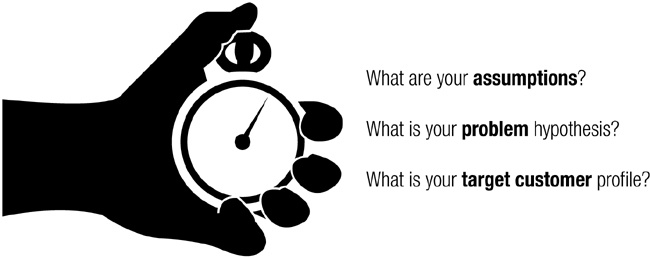

These exercises are a fast and effective way to form initial hypotheses on how you’re going to provide value and make money and who you’re going to target. If you want more rigor (and are willing to invest more effort up front), you may want to complete a Business Model Canvas instead of or in addition to these exercises (see The Business Model Canvas later in this chapter for details).

Exercise 1: Identify Your Assumptions

Along with your product ideas, you have dozens of assumptions. There are things you believe to be true about how your customer thinks and acts, what he is capable of, and how he makes decisions. There are things you believe to be true about how you will produce your product, the resources and partners you may work with, and how you will get your product in front of customers.

You should spend some time identifying your assumptions whether you’re starting a brand-new company, launching a new product to existing customers, or adding a new feature to an existing product. If you are just starting, you may feel like these assumptions are wild guesses; if you are working in an existing enterprise, you may feel highly confident that your assumptions are correct. Either way, you must identify your assumptions explicitly in order to be able to rigorously validate them.

Ready? Set? Go!

Get some pens and sticky notes and set a timer for 10 minutes. Then start writing, as quickly as possible, your assumptions about your customers, product, and partners. If you’re doing this as a group exercise (and I hope you are), don’t stop and discuss during the 10 minutes. The point isn’t to write what you think is correct; it’s to unlock the mostly unspoken assumptions in your head.

Here is a list of prompts to help you bring your assumptions to the surface:

Customers have _______ problem

Customers are willing to invest _______ to solve this problem

Stakeholders involved in using/buying this product are _______

Partners involved in building/distributing this product are _______

Resources required in building/servicing this product are _______

If customers did not buy/use our product, they would buy/use _______

Once customers are using our product, they will gain _______

This problem affects our customers _______

Customers are already using tools like _______

Customer purchasing decisions are influenced by _______

Customers have [job title] or [social identity]

This product will be useful to our customers because _______

Customers’ comfort level with technology is _______

Customers’ comfort level with change is _______

It will take _______ to build/produce this product

It will take _______ to get X customers or X% usage

This is a list of triggers to help you get started. Once you start identifying assumptions, it will become clearer what other beliefs you hold about how you plan to build, design, distribute, and create value with your product.

You may think that there’s no way you’re going to be right about your cost structure or key partners on day one, and that’s probably right. Steve Blank likes to quote boxer Mike Tyson on prefight strategies: “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”[11]

It’s not important that you’re right; it is important that you write down your assumptions. They serve as a critical reminder to you that you haven’t yet proven or disproven them.

After you’ve finished, if you’ve done this as a group, spend another 10 minutes clustering similar sticky notes. For example, put all the sticky notes around “Customers have X problem” together. You’re likely to see assumptions that contradict each other, even within a small group. Finding these internal misalignments will help your product even before you start talking to customers!

You will want to refer back to your assumptions throughout your customer development process—at first as a reference for finding customers and thinking of questions to ask, and later to annotate them as you collect evidence that validates or invalidates them.

Now that you’ve completed a brain dump of your assumptions, it’s time to come up with a simple, provable hypothesis.

Exercise 2: Write Your Problem Hypothesis

Next, you’ll write your problem hypothesis. This is the hypothesis that you will either validate or (probably) come back and revise.

Write your hypothesis in this form:

I believe [type of people] experience [type of problem] when doing [type of task].

or:

I believe [type of people] experience [type of problem] because of [limit or constraint].

Let’s break it down. Your hypothesis needs to consider the five journalistic questions: who, what, how much, when, and why.

The type of person who experiences the problem—that’s who you need to talk to. The type of problem that they’re experiencing—that’s the what, how much, and when that you’ll need to find out. The type of task or constraint—that’s the why that you’ll need to understand.

You want to make each learning cycle as rapid as possible. Each time you’re wrong, you’ll learn a little bit about why you were wrong, which helps you make a more educated guess the next time.

Write down your hypotheses and save them. You’ll be referring to them again later.

Exercise 3: Map Your Target Customer Profile

What does your customer look like, and what about her abilities, needs, and environment make her more likely to buy your product?

Chances are, you don’t know exactly what your customer looks like. Even if the problem is one you’re experiencing personally, it’s hard to know who else is part of your target market.

Start by asking questions like:

What is the problem?

Who is experiencing this problem?

You probably identified a fairly broad audience, such as moms or working professionals. That may represent the audience that will eventually be interested in your product. But anyone familiar with the technology adoption lifecycle knows that not all of these people will be ready to buy or use your product on day one. You need to find and focus on those day one people, found on the left side of the innovation adoption lifecycle (Figure 2-3).

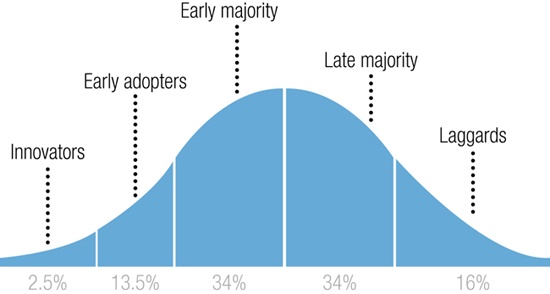

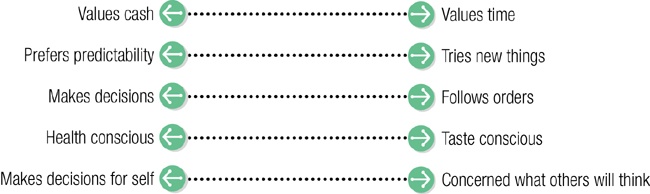

In working with a number of product teams, I’ve found that it’s usually difficult to know where to start. One exercise that works well is to draw opposing traits on a spectrum (Figure 2-4) and ask two questions: is this relevant? And if so, where do we think our customer sits on this spectrum?

What makes a trait important is how it influences the customer to make decisions. For example, if you believe that your target customer values cash, that conflicts with offering a full-featured product at a premium price.

The advantage of the traits spectrum is that it’s visual. I recommend sketching these out on a whiteboard with your entire team and soliciting input as you go. In my experience, doing this helps bring a more diverse set of thinkers into the process. Engineers, designers, and salespeople who might not read a long document will participate in a short whiteboard exercise.

The following lists should get you started, and then you can add criteria specific to your industry or vertical.

If you’re targeting consumers, you might want to start with some of these traits as a jumping-off point:

Cash versus time

Decision accepter versus decision maker

More control versus more convenient

Low-tech versus tech-savvy

Replaces frequently versus long-term purchaser

Values adventure versus values predictability

Enjoys highs and lows versus prefers consistency

If you’re targeting business customers, you might want to start with some of these traits:

Low-tech versus tech-savvy

Low autonomy versus high autonomy

Conservative corporate culture versus progressive corporate culture

Risk-averse versus risks are rewarded

Values stability versus values recoverability

Prefers turnkey solutions versus prefers best-of-breed pieces

You can create a surprisingly full target customer profile using only opposing traits like this. To round it out, you may also wish to ask a few general questions:

What does this person worry about the most?

What successes or rewards does this person find the most motivating?

What is this person’s job title or function?

What social identity (teenager, mom, frequent business traveler, retiree, athlete, etc.) would this person use to describe herself?

Some of you will wonder why you’ve done all this work up front before you start talking to people. Others will wonder why you need to talk to people when it was so easy to come up with very plausible customer profiles on your own!

What this profile does is give some structure to the conversations you’re going to have. Once you’ve been through a few interviews, you’ll be able to take each assumption and say “this seems true—and here’s why” or “this seems false—and here’s why.”

Next Step: Find Your Target Customers

Now that you have a target customer profile, you’re ready to start looking for customers to talk to. Chapter 3 helps you explore who they are, where you can find them, and how to reach out to them and schedule interviews.

[11] This is far more entertaining than Blank’s original version, “No business plan survives first contact with a customer” (http://bit.ly/1iXUUjB).

The Tyson quote is explained here: http://bit.ly/1iXUY2C.

[12] You can get poster-sized canvas images to print at http://www.businessmodelgeneration.com/canvas.

There are alternate versions. Ash Maurya, entrepreneur and author of Running Lean, remixed Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur’s work to produce his version, the Lean Canvas (http://practicetrumpstheory.com/2012/02/why-lean-canvas/). You can find the Lean Canvas at http://leanstack.com/.