Chapter 5. Get Out of the Building

After a short intro, I was able to transition [the interview] to just two people talking on the phone. People were staying far longer than the requested 10 minutes, and I was learning far more than I could have in any other format.

—Nick Soman, CEO of LikeBright

Great products require deep human empathy: you can’t solve for that without talking to the customer early and often. Sitting behind a glass wall and having people do things on a computer—how realistic is that? We should be having conversations with people.

—Kara DeFrias, Innovation Catalyst at Intuit

You’ve written down your hypotheses, found people to talk to, figured out what you need to learn, devised questions to get you there, and scheduled a time.

Now comes the hard part: actually doing your first interview.

I’m going to be honest: I dreaded the first few customer interviews I did.

What if I don’t learn anything useful? What if this feels like a bad first date with long, awkward silences? What if my interviewee feels like I’m wasting her time?

Thousands of interviews later, I’ve learned that you control the tone of the conversation. When you speak confidently, set expectations appropriately, and express genuine curiosity, people talk. When you close with heartfelt appreciation, you build a relationship and people are happy to talk with you again in the future. I still keep in touch with a couple dozen people I met through customer development interviews.

This chapter gives you the tools to create comfortable and constructive interviews. As we walk through the interview process play-by-play, we’ll cover effective tactics and explain why they work. You’ll learn:

How to prepare before the interview

The surprising trick that gets people to open up and talk freely

How to give people permission to be experts

Why you should embrace tangents

The value of thanking people using the foot-in-the-door method

At the end of this chapter, you’ll have all the tools you need to get out of the building and learn some surprising, insightful, and unexpected things from your interviews.

The Practice Interview

Every interview after the first is easier. For that reason, I recommend doing a practice interview with someone you know who is not one of your target customers.

A practice interview won’t validate your hypotheses, but it will give you the opportunity to test the process and improve your interview techniques before moving on to real subjects.

The practice interview can also be helpful if you already have a product and customers. Sometimes you’ll need greater sensitivity when talking about hypothetical ideas with people who’ve already written you a check, and it helps to walk through that in advance with someone who understands (i.e., a colleague, not the customer).[39]

Who should you interview for this dry run? While your practice interviewee doesn’t need to meet any particular criteria, it’s a good idea to choose someone who isn’t too closely related to your idea. It can be challenging to keep a straight face if you interview your partner or best friend. A more distant coworker, or a nonstale LinkedIn connection, may be a better choice.

At Yammer, my team often tests interviews on new hires who aren’t yet familiar with the interviewer or the product. No special instructions are needed; we just tell them to answer the questions based on their own experiences or opinions. After the interview, we ask them for feedback on the interview itself. That’s a good idea, no matter who you choose for your practice interview.

To Record or Not to Record?

You might wonder, “What about making an audio recording of my interviews?” If you’re thinking of recording, you may be worried that you can’t write or type quickly enough to capture verbatim comments, or that the conversation will feel awkward because you are writing instead of making eye contact with your interviewee.

Here are some pros and cons of recording the audio of your interviews:

Pros:

You’ll capture everything your interviewee says.

You won’t inadvertently bias your notes (writing down a milder or summarized version of what the interviewee said).

You can focus on body language and facial expressions.

Playing back audio from a real person speaking, with pauses and intonation, is more powerful than sharing a verbatim quote.

Cons:

Asking if you may record the conversation is an awkward beginning to the interview.

Recording interviews effectively doubles the amount of time per interview since you need to go back and listen to the interview a second time to capture notes or excerpts.

Interviewees may be more cautious when they know they are being recorded. (And no, recording without their permission is not an acceptable workaround.)

Employees may be subject to their employer’s legal restrictions, even if they’re not talking about their own products or processes.

Taking notes manually (by hand or typing) is a valuable hack to keep you from talking, encouraging interviewees to talk more.

The right approach is the one that helps you run effective interviews. You’ll probably want to try both ways to figure out which you prefer.

The format of your interviews may influence how you decide to capture notes. I conduct most of my customer development interviews over the phone, where no one can see that my eyes keep flicking back to my laptop screen. However, I don’t feel comfortable typing into a laptop during a face-to-face interview. While working on this book, I’ve discovered that I can no longer write by hand fast enough to capture verbatim quotes. I just don’t write by hand often enough to maintain that speed!

Whether you record your conversations or take manual notes, though, you’ll need to spend a few minutes after each interview synthesizing the highlights. If you leave your notes untouched and come back several days later, it won’t matter whether they’re three pages of handwriting or 30 minutes of voice recording—either will be unapproachable!

Taking Great Notes

Taking notes during customer development interviews requires something that might at first seem strange. I want you to forget everything you know about note-taking from school or from meetings.

If you take notes in that style, you’re wasting your time. When you take notes in a lecture or during a meeting, you summarize. You make deliberate choices to omit some points, condense others, and translate some of what you hear into what you think the speaker was actually trying to say. If you’re taking notes in a work meeting, you may have to share them with a wider audience and sanitize or contextualize what you write accordingly.

When you’re doing customer development, you don’t know what’s important yet. You won’t know what’s important until after you’ve completed a number of interviews.

It’s critical to capture as much information as possible—in high-fidelity, with details, emotion, and exclamation points. If your interviewee says, “Using product X is literally the worst part of my entire week,” that is not the same as “Customer doesn’t like product X.”

Obviously you can’t write down every word. (You probably don’t want to, either; at some point you have to go back and read all these notes.) As a guide, remember that you’re using what you learn to validate hypotheses and find out more about your target customers’ pains. You need the most detail when the interviewee says:

Something that validates your hypothesis

Something that invalidates your hypothesis

Anything that takes you by surprise

Anything full of emotion

When you hear any of these things, mark them emphatically in your notes. Circle them, bold them, or highlight them to ensure they stand out later. If you’re recording the audio of the interview, write down timestamps when any of these interest points occur so that you can easily reference that portion of the conversation later.

People often ask, “Why is emotion so important? What if the person is just complaining about something unrelated to my product idea?” Emotion—and by that, I mean complaining, anger, enthusiasm, disgust, skepticism, embarrassment, frustration—is prioritization. If you want to know what’s important to someone, don’t ask them for a list: you’ll hear what they intellectually think ought to be important to them. Instead, listen for emotion when they talk. Those are the areas of opportunity. Even if what they are saying seems unrelated to your product idea, it will help you flesh out a greater understanding of your target customer.

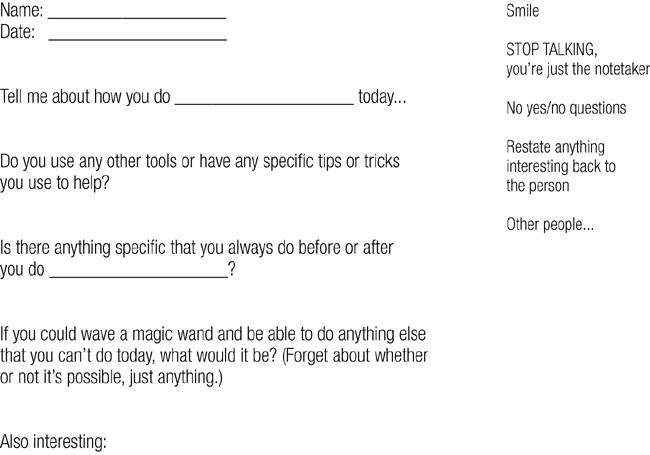

Another note-taking challenge is that every conversation flows differently. (If your interviews don’t, you aren’t letting customers drive the conversation enough.) But you’ll eventually need to be able to compare across dozens of conversations. You can make this easier by using a template for taking notes for each interview.

Your template should be flexible enough to work for a variety of conversations, but structured enough to ensure you cover the most critical three or four questions with each interviewee. I’ve also found it useful to include some reminders to myself about what to do and what not to do on my template (see Figure 5-1).

Invite a Note-taker

At Yammer, when we do customer development interviews, we improve the interviewer’s ability to focus on the interview itself by inviting a second person to take notes (see Pair Interviewing on the next page).

Inviting someone to take notes is a great way to get people from other cross-functional teams in front of customers! We have coworkers who would never agree to conduct an interview but who are willing to help us out by taking notes. (This is not to say there wasn’t initial resistance to taking notes for us. We needed home-baked cookies to entice our initial volunteers. But after about six months, we are now able to require at least one hour of note-taking participation from everyone on our product teams.)

We use an online note-taking template with the sections already described: validates, invalidates, surprising, and emotions. The note-taker brings his laptop into the room and types directly into the template. This way, notes are in a consistent format, searchable, and no one needs to transcribe.

Immediately Before the Interview

Familiarize yourself with the person you’re about to talk to. If you’re targeting someone in the workplace, look at her job title, the type of company she works for, and the industry she’s in. If you’re targeting a consumer, look at whether she’s single or married with kids, suburban or urban, tech-savvy or not. Take a minute to put yourself in her shoes and think about the types of things she’s likely to think and worry about.

During your conversation, you’re likely to make ad hoc references or give examples. Your interviewee will feel more comfortable, and be more willing to talk freely, if he can relate to those references.[40] (For example, a single guy who lives in the city is less likely to relate to a reference about shuttling kids around in an SUV.)

Don’t forget the really mundane. Use the restroom. Get a drink of water. Have extra pens and paper on hand. Your phone should be charged and silenced. If you’re typing, remove all distractions. Close your IM client, your browsers, your email, and get rid of any other potential distractions. (I usually disable my WiFi.) Get your note-taking template in front of you and get ready to start writing or typing!

The First Minute

As you dial your interviewee’s number or wait for her to arrive, you probably feel a bit nervous and unsure about what to expect. So does the person you’re about to interview.

Most people have never done anything like a customer development interview before. Even if they’ve participated in usability testing or traditional marketing focus groups, those follow quite a different format. Usability testing and focus groups have more structure and moderation. Both are typically oriented around an existing product, service, or prototype. Because you kept your initial interview request brief, your interviewee isn’t entirely sure what to expect.

It’s your job, in the first minute of your conversation, to do three things:

Make the interviewee feel confident that she will be helpful

Explicitly say that you want her to do the talking

Get the interviewee talking (I’ll explain how)

The beginning and the end of the interview are the only times where I recommend that you rehearse what you’re going to say in advance. Having a script for the beginning of your interviews helps you to sound confident and set expectations appropriately. A good opening script for a phone interview might look like this:

Hello, this is [Name] from [Company]. Is this still a good time to talk?

Great! First of all, I’d like to thank you for talking with me today. It’s incredibly valuable for me to get to listen to you talk me through your personal experience and how things work (and don’t work) in your world, so I’ll mostly be listening.

Could you start by telling me a bit about how you [perform general task] currently?

Sounds pretty basic, but there are some very specific elements that make this an effective opening. Every time I’ve deviated from these, or worked with a company that has, the quality of responses goes down. Those elements include:

- Keeping the tone conversational

If you’re from a conservative industry, like finance or healthcare, you may think that this introduction is too casual and that you’ll need to adopt a more formal tone. What I’ve found is that using more formal terms correlates with shorter, more sanitized answers. If you’re talking to an employee, you don’t want to hear the official process; you need to know all the secret grumblings and workarounds that people have patched together to get their jobs done. Those are the insights you need to build an incredible product. Talk the way you’d talk in the break room, not the way you’d speak in an executive presentation.

- Being human

When you’re talking, use “I” and “me,” not “we” or “company.” People are more likely to help someone they have a connection with than a faceless “we” or company. Social psychology research bears this out.[41]

- Emphasizing the personal

Using phrases like “your personal experiences,” “for you, specifically,” or “in your world” may feel awkward at first. However, it helps emphasize that the interviewee is the expert and that his specific opinions and behaviors are valuable. It’s very common to hear people demur, “Oh, I’m just an ordinary [fill-in-the-blank]; you can’t be interested in what I have to say.” You need to help the interviewee overcome that hesitancy in order to draw out detailed answers.

As long as you preserve those elements, you can (and should!) adapt your opening to fit your personal speaking style and your company.

The Next Minute

You’ve just finished your opening script and explained how vital it is that your interviewee—the expert—share everything he knows. Here’s what will naturally happen: your interviewee doesn’t want to dominate the conversation (even though you just encouraged him to do so!). He’ll say one or two sentences and stop.

How do you convince someone to violate our ingrained social norms and keep talking?

You shut up and listen. You say your opening bit, you ask the first “Tell me about how you...” question, and you wait. Look at the clock and don’t say another word for a full 60 seconds (Figure 5-2).

Sixty seconds is a long time. You will want to say something to break the silence or move to the next question. Don’t. By jumping in too quickly, you signal that the interviewee has said enough and that you’re not interested in hearing more. He will take your attempt to break the silence as an indicator that one or two sentences is the right level of detail and will start giving you short, shallow answers. That’s not what you want at all!

Instead of talking, let the silence happen.

I recently saw a tweet that suggested literally hitting the mute button on the phone to prevent yourself from talking. I actually don’t recommend this: it’s noticeable when the other end of the line goes completely silent, and it sounds like a dropped call. You don’t want your interviewee to interrupt themselves to ask, “Hello? Are you still there? Did I lose you?” Keep the subtle sounds of you breathing and listening audible.

If you remain quiet, most people will then continue to talk,[42] and it’s usually those details—not the summary—that contain the useful insights. (If your interviewee doesn’t start talking again, or seems genuinely uncomfortable, you may need to provide a verbal nudge. Typically you won’t need to.)

Forcing him to keep the conversation going in the first exchange sets the tone. You really meant what you said; you are mostly going to listen. Now your interviewee knows that it’s OK to give long, detailed descriptions.

Keeping the Conversation Flowing

After the initial “tell me about how” question, your interview can be as freeform as needed.

You may find yourself asking each question on your list in turn or spending 10 minutes on a single question because your interviewee can’t stop talking about it.

The most important thing is to keep your interviewee talking and subtly encourage her to go into more detail about the things that she gets most excited about.

Warning

Don’t keep doing the “stay quiet for 60 seconds” trick. It works incredibly well to kick off your interview the right way, but it can feel cold or manipulative if you overuse it. Pausing to ensure that you don’t interrupt or cut off your interviewee is good, but you can keep the pauses to two or three seconds. Once you’ve got a person talking, you want to make him feel like the expert. That requires you to be an active listener—acknowledging what the person is saying and asking questions.

Keep asking questions to draw out as much detail as possible. You want to encourage longer answers. The best prompts are open-ended and don’t lend themselves to a yes-or-no response:

How long does that process take?

Why do you think that happens?

What’s the consequence of that happening?

Who else is involved with decisions like this?

Where else do you see this kind of mistake?

When was the last time you did that task?

Asking this type of follow-up question doesn’t just keep the person talking; it can entirely change the tone of his response. Read this exchange from an early interviewee with KISSmetrics, a web analytics company:

Customer: We’re already using some analytics tools that our engineers built custom, and that seems to work fine. We can see conversions and traffic and get reports when we need them.

This seems like an uninterested customer. He’s telling me he already has a solution to his pain point. He isn’t expressing frustration. He isn’t complaining about things he can’t do.

Time to move on to the next question? Not so fast. You’ll want to ask at least one follow-up question to make sure that there’s nothing interesting here:

Interviewer: You said you can get reports when you need them. When’s the last time you needed a report?

Customer: Last week. Well... we could’ve used some data last week, but actually the engineer who runs the reports was in the middle of fixing some big bug, so I had to wait a couple days to get it.

Interviewer: How often does that happen, that you need some data but have to wait to get it?

Customer: Well, it happened last week. And probably a couple times this month. But it’s more important for engineers to be working on bug fixes or features than to run reports. [long pause] Yeah... I guess I end up making decisions based on my best guess instead of having numbers.

Interviewer: How important do you think those decisions are? What is the consequence of not having those numbers?

Customer: Honestly, it hasn’t been that important with what we’ve done so far. But we’re about to make some changes that directly affect monetization. If we make wrong guesses there, we lose money. Pretty direct connection. Ugh! I’ve been so busy I hadn’t thought about this yet, but this is really urgent....

Avoiding Leading Questions

Be careful with your follow-up questions. It is very easy to accidentally ask leading questions. Once you’ve asked a leading question, you have biased your interviewee’s response. Leading questions are often constructed like:

Don’t you think ______?

Would it cause a problem if _______?

Would you agree that _________?

Would you like it if _________?

This structure often leads to the interviewee starting his answer with “yes” or “no.” You may not realize that you just asked a leading question, but if your interviewee starts an answer with “yes” or “no,” you probably did. Mark it down in your notes so you know to treat that answer with skepticism.

Of course, there will be plenty of occasions where the interviewee isn’t saying anything interesting even after you’ve nudged him some more with follow-up questions. Don’t force it. Not every question is productive for every person. Move on to your next question or topic.

Digging a Little Deeper

At the end of a long series of questions, you may think you understand a specific situation or problem. Your instinct will be to simply agree, saying “yes” or “I get it.” Don’t do that just yet. There will often be some detail you misunderstood or that the interviewee omitted. Instead, ask for clarity. A good format is to state what you’re doing, summarize what the person said in your own words, and explicitly ask her to correct you. I recommend restating the interviewee’s words any time she says something particularly interesting (or surprising), as well as at the end of a series of questions before you move on to another topic.

Summarizing what the person said back to her can feel awkward, even condescending. (Just the phrase “active listening” conjures up memories of well-meaning kindergarten teachers or old Stuart Smalley sketches on Saturday Night Live.) You may be tempted to skip this step because it feels unnatural. Summarizing what the interviewee says gets easier, and you’ll save yourself a lot of misunderstandings.

Here’s an example from a recent interview with a Yammer user:

Me: I want to make sure I’m clear on this: you’re saying that you send files over email because it’s hard to log in to the secure intranet file-sharing site, because it’s easier to send them via email. And you share files over email about twice a week? Did I get any of that wrong?

Interviewee: No—I mean, I do have problems with the login thing, but the main reason we use email is that our sales guys are always on the road and they can’t get to the intranet; they can only get to their email.

So we have to use email. That happens maybe twice a week, except for the end of the quarter, when all of sales is racing to get deals done and then we’re sending, like, 20 files over email every day.

In her response, the interviewee actually identified a different and more important problem! She also realized that this isn’t just an everyday pain point; it gets worse at specific high-priority intervals.

These are exactly the type of details that a person wouldn’t usually reveal in her initial answers. Interviewees aren’t trying to hold back information; they just haven’t thought about it from an outsider’s perspective before.[43]

Tangents Happen

The open-ended nature of these interviews means that your interviewee will spend some time talking about seemingly unrelated problems or situations. “Why is he talking about this instead of what I want him to be talking about?” you’ll wonder.

That’s a question worth exploring. Why is this person talking about a seemingly unrelated topic? If a person brings up a topic, it’s probably because it’s important to him. Maybe it represents a more pressing problem that you should be solving instead. It could be a necessary precondition, something he needs to worry about before he can think about your idea. It might reveal that this person is not the person you should be talking to.

Instead of redirecting the interviewee back to your question, I recommend taking at least a minute or two to explore the tangent. Some questions that may be useful are:

Do you spend more time on [tangent] or on [original idea]?

How many people are involved in doing/thinking about/approving/fixing [tangent]?

How high a priority is [tangent] in your home/workplace?

If it’s clear that the interviewee devotes more time and priority to the tangent, you may ask him to refer another interviewee. (Please don’t insult the interviewee by asking if there is someone better to talk with—you never know when you may want to revisit a past interviewee.) Here’s one way to make that request:

Right now, my plan is to focus on [original idea] more than [tangent], so I don’t want to take up too much of your time. If I do end up thinking more about [tangent] in the future, can I get back in touch with you?

One last question: if I wanted to learn more about [original idea], do you know someone I should talk to?

Even if you initially think that a tangent is unimportant, you won’t really know for sure until you’ve talked to enough people to start seeing patterns. When I did customer interviews for KISSmetrics, many people veered away from talking about analytics to complain about how difficult it was for them to do qualitative user research and surveys. When the first person said this, it seemed like an outlier. Once five more people talked about the same problem, and then more, it was clearly an opportunity. (One of my more popular lines in conference talks is “One person might just be a nutcase. Ten people are not all nutcases.”) That tangent was the inspiration for a whole new product! KISSinsights, now called Qualaroo, powers on-site surveys and targeted interactions for thousands of companies.

Typically a tangent will run its course after two or three minutes and you can simply ask the next question. If not, you can simply interject to apologize and say that you want to make sure that there is time to get to the next question.

Avoiding the Wish List

Some people will evade your questions and say, “Here’s what I want.” They’ll start listing features and options; I’ve even had people start sketching mockups in coffee shop meetings!

On the surface, this sounds amazing: a prospective customer practically writing your product requirements for you. The truth is different: thousands of failed products are created based on what customers said they wanted. You’ve probably worked on at least one of them in the past.[45]

You don’t need to learn what customers say they want; you need to learn how customers behave and what they need. In other words, focus on their problem, not their suggested solution.

Away from Features—Back to the Problem

As soon as a person starts talking about feature ideas or specific solutions, quickly redirect the conversation. This takes some delicacy because you don’t want to imply that her ideas aren’t good. Her feature ideas may actually be great; they’re just not what you need right now. The most common transition I use is to ask how a requested feature or sketch would solve her problems:

You’re saying that you’d like [feature]? Could you walk me through when and how you would use it?

[Listen to her answer, then transition from feature to back to problem]

So, it sounds like today you have the problem of _______. Is that accurate? Can you tell me more about this problem? I want to be sure I fully understand it so we can work on solving it.

The problem of interviewees suggesting features is even more of a challenge if you have an existing product and customers. People who have already paid you money or signed a contract feel that they have earned the right to make feature requests. (If they’ve paid enough money, they also expect you to tell them how long it will be until that feature is built and released.)

Business innovators often cite the alleged Henry Ford quote, “If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse.”[46] You can imagine the customer development interview that might have occurred back then:

Customer: I need a faster horse. When are you going to build one?

Interviewer: I want to make sure that whatever we build truly solves your problem. Can you tell me, if you had a faster horse right now, how would that make your life easier?

Customer: I’d be able to get to work faster, of course!

The Magic Wand Question

What customers ask for is constrained by what they already know and is often not the best solution. They may even feel embarrassed to mention ideas that they don’t fully understand. That’s an incredibly limiting perspective. The question that helps open their minds is the magic wand question:

If you could wave a magic wand and change anything—doesn’t matter if it’s possible or not—about [problem area], what would it be?

It’s a little bit silly, and that’s deliberate. The mention of a magic wand is unexpected in a conversation between adults—it makes people smile and loosen up. Magic wands don’t know about regulations or org charts or technology limitations—they just get the job done. In a consumer context, magic wands address more basic human constraints. Like fairy godmothers, magic wands are not limited by time or money.

By freeing people up, the magic wand question allows people to talk about larger, more complicated pain points. (It’s not uncommon for a prospective customer to ask for something impossible that isn’t at all.) That adds up to more attractive problems for you to solve.

Get in the habit of asking this question. You’ll use it a lot. People are wired to make suggestions and ask for specific solutions, not to describe their problems. This style of questioning won’t result in a customer inventing the Model T, but it will shift him to thinking in terms of the underlying problem.

Once you’ve asked the magic wand question, you can explain a little bit about what you’re trying to do:

In the past, we’ve worked on products that were supposed to do something specific, but they didn’t solve the real problem. We’re trying to avoid that and make sure we build something that will help with your situation and address the things that make your life harder.

That’s a message that almost any customer will understand—we’ve all bought products that didn’t deliver what they promised.

Avoiding Product Specifics

What if the interviewee starts asking specific questions about your product? Especially if she is highly motivated to solve this problem, she will be eager to see what you’re building.

You may or may not have a product in progress, but in any case, it’s best not to show the interviewee your product or talk about specifics until the very end of your conversation. Better yet, schedule a separate interview for talking about solutions.

Why is it a bad idea to show your product at this stage? The reason is that images or tangible specs will taint everything that your interviewee was going to say. Instead of thinking about how she works and her frustrations, she will subconsciously tailor her answers based on your product. (This is a variation on the “If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail” principle.)[47]

If an interviewee is eager to see your product or visuals first, you can explain that you’d like to hear about her experiences and frustrations first so that she’s not influenced by what already exists. You can always offer to schedule a follow-up demo in the future, but once you’ve shown something, you’ll never be able to go back and get pure feedback from this person.

If you don’t have anything to show yet, it’s OK to say so. You can say something like “We are hoping to solve the problem of people managing their personal finances, and in order to do that really well we need to first understand exactly what people are doing today and where they are struggling.”

Going Long

You asked for 20 minutes of a person’s time, but sometimes you’ll find that he is still talking enthusiastically past that time. (That’s why I don’t recommend scheduling back-to-back conversations every half-hour.) Even if your interviewee seems eager to continue talking, he may have lost track of time. You don’t want to inconvenience him by inadvertently making him late to his next commitment. If you near the 30-minute mark and he is still talking, it’s a good idea to gently interrupt with “Excuse me—I’d love to continue the conversation, but I don’t want to take up too much of your time.”

I don’t recommend extending interviews much beyond the 45-minute mark, no matter how enthusiastic you both are. You’ll get diminishing returns and risk using up that person’s goodwill. A better approach is to request permission to contact him with follow-up questions.

It is tempting to try and cram as much as possible into your initial conversation. What if this is the only opportunity you get to talk to him? It’s counterintuitive, but doing one favor for you actually primes people to do a second one. Have you ever been asked for a small charitable donation, and then been hit up for a larger one later? That’s the foot-in-the-door technique, and it’s much more effective than asking you for the big bucks in the first interaction.[48]

Offer to schedule a second interview once you’ve learned more or have some early sketches to show. Remember, some of the target customers you interview early on are likely to become your future evangelists—even if what you end up building is completely different from where you started.

The Last Few Minutes

Just as the first minute is critical to get someone talking, the last minute is critical to building a relationship with her. You don’t want the interviewee to regret having given you the last 20 to 30 minutes of her time.

It’s your job, in the last few minutes of your conversation, to do three things:

Offer some of your own time to the interviewee

Make the interviewee feel that she succeeded in helping you

Thank her personally for giving her time

Whatever you say, it must be personal and genuine. This isn’t the conclusion of a business transaction; it’s the end of a conversation with someone you probably want to talk to again in the future. Here’s what I say, but make sure what you say works with your personal speaking style:

[Name], I think you’ve answered all the questions I had. Is there anything I can answer for you?

[Pause, answer questions as needed]

Thank you so much for talking with me today. It was really helpful for me to hear you talk about [repeat a problem or situation the interviewee discussed]. That’s the type of detail that it’s just impossible for me to learn without talking to real people who are experiencing it.

Can I keep you in the loop as I continue to learn more? If I have further questions, or once I’m closer to building an actual solution, can I get back in touch with you?

[Pause]

Thanks again, and have a good rest of your day!

This is another application of the foot-in-the-door technique. By asking people if you can contact them again, you’re reinforcing their role as the expert. You’re asking them for a favor, but it feels like a compliment.

I frequently come back with follow-up questions, either later in the process when I think I’ve spotted a pattern and need some more data points, or once I have a minimum viable product to show the customer.

After the Interview

The process of interviewing should be every bit as iterative as the process of building your product. In other words, you won’t get it right the first time. You’ll need to keep assessing what you did and how well it worked, and fine-tuning the areas that didn’t work as well as you would have liked.

While the interview is still fresh in your mind, take five minutes to ask yourself or your note-taker the following questions:

Did the opening minute of the interview go smoothly? Did the interviewee start talking right away?

Did I unintentionally ask leading questions or offer an opinion that may have biased what the interviewee said? (You probably won’t notice if you did this. If you worked with a note-taker, he is more likely to have caught these slip-ups.)

Did any of my questions lead to very short or bland answers? Is there a way I could revise them to be more open-ended and effective?

Did I ask any questions on the fly, or did the interviewee bring up any questions or ideas that I should add to my interview template?

Was there anything that I wish I had learned but we just didn’t get there? How could I get at that information next time?

Where did the interviewee show the most emotion? Which questions prompted the most detailed and enthusiastic replies?

If you don’t run through this checklist immediately after the interview, you will forget a lot of vivid detail. You’ll always have your notes, but that subjective feeling of what went well and poorly fades quickly.

This is also a good time to focus on the subjective qualities of your conversation. What was the dominant emotion this person expressed? Anger, giddiness, frustration, shame, curiosity, excitement? If you had to summarize the tone of the conversation in one sentence to a friend, what would it be? I’ll focus more on analyzing your notes in Chapter 6, but this isn’t about analysis—it’s about your gut feeling. Jot it down now before it fades away.

Take some time before your next scheduled interview to adjust the areas that need improvement. Then start the process all over again!

Get Out (Now!)

Now it’s time to stop reading. Put the book down and go talk to a customer.

We’ve covered the questions to ask, the techniques for getting people to talk, and the prompts that keep them talking. The only missing ingredient is you taking action. I’m watching you: don’t start reading Chapter 6 until you’ve done at least two interviews. Get out of the building!

[39] A lot of things about customer development may change if you’re working with existing customers, but not the fundamental psychology of how to get people to talk. We’ll talk about those changes and risks in Chapter 8. I recommend reading this chapter first and then thinking about how to adapt what you learn to your situation.

[40] Zappos’s customer support attempts to create a personal emotional connection on every support call. Geographical call routing attempts to connect you to a support professional in the same location to increase the odds that you’ll have something in common. This emotional connection is one of the reasons why 75% of Zappos’s business is repeat business from existing customers. For you, fostering this connection will help some interviewees become your cheerleaders and advisors.

[41] This is probably due to the relationship between self-disclosure and likeability: people who reveal personal information about themselves are more often liked by others (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7809308). Even if all you reveal is your name and enough personality to demonstrate that you’re not reading a script, that’s probably sufficient.

[42] I’m sure there’s a legitimate social psychology reason for this, but I’ll cite Pulp Fiction instead:

Mia: Don’t you hate that?

Vincent: Hate what?

Mia: Uncomfortable silences. Why do we feel it’s necessary to yak about bullshit? In order to be comfortable?

Vincent: That’s a good question.

[43] Or they’re suffering, as we all do, from the “curse of knowledge.” People who build products become so familiar with those products that they assume that everyone knows how to perform a task or find a feature. People who use products assume that everyone understands how those products are flawed and how they fail to align with how people really work. As author Cynthia Barton Rabe says, “When experts have to slow down and go back to basics to bring an outsider up to speed, it forces them to look at their world differently and, as a result, they come up with new solutions to old problems” (quoted in “Innovative Minds Don’t Think Alike” by Janet Rae Dupree, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/30/business/30know.html).

[45] There’s a terrific episode of The Simpsons that illustrates this point. Homer discovers he has a long-lost half-brother, Herb, who owns the fictional Powell Motors company. When Herb encourages Homer to design a car for the average American consumer, Homer includes shag carpeting, an isolation bubble for the kids, and three horns that play “La Cucaracha” when honked. Naturally, no one actually wants to buy a car like that, and Powell Motors goes out of business (http://simpsons.wikia.com/wiki/The_Homer).

Entertainingly, a team actually built the Homer for the 24 Hours of LeMons race (http://techland.time.com/2013/06/27/finally-homer-simpson-designed-car-the-homer-comes-to-life).

[46] There’s no evidence that Henry Ford ever said this, though many people, including his own great-grandson, have attributed it to him. See http://quoteinvestigator.com/2011/07/28/ford-faster-horse/.

[47] This concept was popularized by Abraham Maslow, who wrote in The Psychology of Science, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” I prefer the earlier usage by another Abraham. Abraham Kaplan said, “Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters requires pounding” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_the_instrument).

[48] The Wikipedia article on the topic describes the foot-in-the-door technique this way: “When someone expresses support for an idea or concept, that person is more likely to then remain consistent with their prior expression of support by committing to it in a more concrete fashion” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foot-in-the-door_technique).

The most often cited examples of foot-in-the-door research date from social psychology experiments done in the 1960s. A more recent meta-analysis of foot-in-the-door tactics (http://psp.sagepub.com/content/9/2/181) questions the strength of the phenomenon.

Nonetheless, I’ve seen it work. If your prospective customers aren’t responding to your follow-up emails, I’d hesitate to blame social psychology and take that as a cue that the problem you’re solving is not compelling enough to warrant further attention.