What is Explicit Cost Dynamics?

Explicit Cost Dynamics is what resulted from the cash flow modeling I mentioned earlier in the book that was created to address challenges that were created by accounting. At the time, I had not understood the differences between costC and costNC. I thought all costs should be defined as what I now call costC and that would ensure they were aligned with cash flow. This was an area of major contention with many in the accounting field. They defined costs differently, and so when we would talk about costs, although we used the same word, what we were talking about was vastly different.

The idea behind ECD is fairly simple. At its most basic level, ECD looks at what your cash obligations are and provides information about what is required to become cash-wise profitable—to have a positive profitC. It is entirely based on math and cash.

The approach starts with modeling cash obligations. If you stop all activities in your company, everything, what would you be paying for? In most cases, you’d be paying for input capacity. Again, that’s your people, space, materials, information technology, and equipment. Next, what other costC would you incur as you start to transact business? This could be anything from costs to take care of facilities, maintenance, and service contracts, to the costC from selling new opportunities or any other types of cash-based transactions associated with operating the company. All of these costs will exist as a part of normal operations. However, clearly documenting and understanding input capacity is a huge component of getting the model right when it comes to modeling cash outflows.

This becomes your costC basis. You need to make sure you’re selling enough to offset these costs so that profitC is positive. This is different from accounting profit or profitNC.

To have a positive profitC, you have to generate more cash revenue during the period than you spent in the same period. Most of this revenue will come from selling products and or services. Sometimes, companies will incur costs, costC, to provide the products and services. For example, assume to provide the services you offer, you have to contract work with a third party to help you execute the services. This may be a cash transaction incurred specifically due to and because of delivering your services. Your selling price must be greater than the costC incurred in executing or implementing your product or service. Note, if your people are involved in delivering the solution, it is costNC, and is not considered in this calculation, only the calculation of the cost obligations.

This leads to the idea that there are two levels of profitC that must be considered. Overall, the company should focus on having a positive profitC, consider it a macro profitC. Second, there is a profitC associated with providing your products and services, a micro profitC. The micro profitC you make from selling your products and services contributes to paying off the capacity and transaction costs you incur while running your company so that you can have a positive macro profitC. One client called this giving back to the kitty, suggesting that all projects have to give back enough to make the company cash-wise profitable. On the surface, one would propose that accounting can do the same thing. This is not true. Let me explain.

In the first part of the book I talked about why accounting profit was very different from cash flow. There were three primary reasons. First, accounting does an extremely poor job modeling cash. Second, capacity and transaction costs are not made salient by cost accounting, so there is no focus on them. We have discussed these two. Third, the idea of contributing cash sounds a lot like contribution margins. They are not really close to one another. Let’s discuss this one further.

Contribution Margins and Fixed Versus Variable Costs

I noticed a number of clients and prospects who have used the idea of a contribution margins. Contribution margins seek to understand the cash contribution of an order. The basic premise is: When you create a product, perform a service, or fulfill an order there is interest in knowing the cash contribution of that order. People recognize the idea that there are costs that have nothing to do with the order, costs such as overhead. These costs are considered fixed. Instead of looking at the margin on the product, service or order by subtracting the “total” cost, why not subtract just the variable component? If you subtract the variable costs from the revenue, you should have the cash contribution. The most common costs that vary from an accounting perspective are materials and labor.

Although the logic makes sense, the approach does not work for two reasons:

1. Variable costs do not vary from a cash perspective.

2. Cost of goods sold is too limited in scope.

Fixed and Variable Costs

Accounting has this idea of fixed and variable costs. A fixed cost does not change with output. Variable costs do change with output. So, assume you’re calculating the cost of a single item. Costs that may be applied to that product, such as supervision costs, may not change as you increase output. However, increased output increases labor and material costs, again, from an accounting perspective.

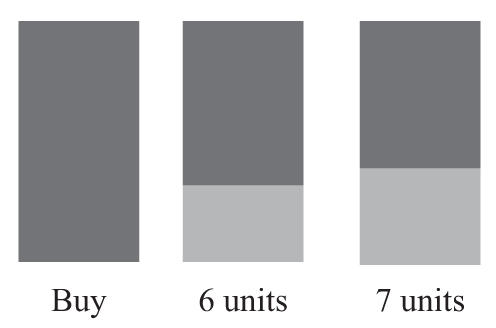

Accounting has this all wrong from a cash perspective. When you buy someone’s time and the materials they will use to make things that you sell, the cash is in the transaction of acquiring them. Their costC is independent of how you use them, yet accounting seeks to assign that cost to the output anyway. Recall, costing a local phone call. If each piece of output consumes labor and materials, these costs are seen as changing, hence variable (Exhibit 19.1). This value is costNC. Mathematically, cumulative costNC should increase as you consume more capacity. However, costC stays the same.

Exhibit 19.1 Doing work will consume input capacity. Since accounting seeks to put a cost on consuming input, the more input you consume, the greater the total cost. Notice costC doesn’t change, although the accounting cost increases

When accounting discusses fixed and variable costs changing, they may be costC or costNC. An example of costC that changes may be utilities, where you may use more to create more. However, with most contribution margin calculations include values that are costNC and do not vary from a cash perspective. Since they do not vary from a cash perspective, the answer the contribution margin gives you will not reflect your cash dynamics.

CostC varies only with how much you buy, the price you pay, or both. That is it. If you want to focus on how, what, and why cash costs vary, look at what you are buying and how you pay for it and not at accounting’s definition of what is fixed and variable.

Scope of Analysis

Many contribution margin (CM) analyses focus on the gross margin (Equation 19.1):

The problem is, there may be costs outside the gross margin analysis that may change with a new order. For example, what if you have to pay transportation costs, taxes, or you take foreign exchange hits to cash with each order? These are often not considered in contribution margin discussions, but may be cash values that exist or are created due to fulfilling an order. Additionally, contribution margin analyses will not predict the need for additional capacity. Assume, to meet an order, you need to buy new equipment. There may be a cash transaction involved with fulfilling this order that will not show up in a gross margin analysis.

When you consider these factors, clearly accounting and contribution margins are ineffective at understanding and modeling cash transactions. If we want to manage and improve cash flow management, we must focus on cash flow, not accounting metrics.

Focusing on Cash Using Capacity

The objective, ultimately, is to make more cash than you spend. The way to know whether you are doing this is to focus on, and manage cash inputs and outputs. To get your arms around what you are spending, focus on cash transactions, especially capacity. When considering cash requirements from revenues, you must be aware of how much cash you need to cover your obligations and the rate you are bringing it in.

Most cash inputs come from sales transactions. There should be targets for how much cash your organization should bring in on a periodic basis to offset its cash outputs. It is amazing how many companies do not know this simple information. It is mostly because people tend to focus on accounting data instead, and assume that if the accounting data suggests you’re profitable, then you are cash flow positive. We know this is not true, and here is a very dangerous example; pricing based on margins.

Many companies will price based on adding a margin to their costs. First, what cost are they going to use? Remember, there are several ways to calculate a cost. Second, although the concept seems right, let’s create a simple scenario. Let’s say a company creates pencils and it calculates the cost to be $2. The company decides it will mark up the pencils to $2.50 so that it makes $0.50 off each pencil. Let’s say the company sells 100,000 pencils. It should have made $50,000. What if the operating costs were $60,000? From an accounting perspective, you have not made enough money even if every transaction was profitable. With ECD, the focus is on understanding what your operating costs are and what you need to generate to cover them. If you have $60,000 in operating costs, you will need to sell enough pencils at such a micro net profitC so that the cumulative profitC covers the $60,000 at a minimum. If you adjust the price so that the net profitC on each pencil is $1, you will need to sell 60,000 of them. If the net profitC is $5, you will need to sell 12,000 of them. This approach, as with capacity, provides clearer guidance and clarity when used. It is tomatoes and garlic. Cost plus with allocated costs is spaghetti sauce.

If you know how much revenue you have coming in and how much you have going out, and if you model and manage this effectively, you will be in a position to assess your cash flow position accurately and make decisions that can improve it. Operationally and from the perspectives of the market and growth, you will want to grow the difference between revenues and costC, but you know that if you’re bringing in more money than you spend, you will generally be okay.

This is what ECD is about. With input capacity at its core, it provides information about how much cash you are spending, where it is going, and helps you understand your overall cash position. It is the tool that is used to model cash flow and provide simple and powerful information back to leaders without overwhelming them with irrelevant data and information. Along with capacity dynamics, ECD creates a comprehensive and powerful way to see, understand, and manage all activities throughout an organization.

One of the weaknesses of the approach as it was developed is that given its focus on costC, it failed to acknowledge and offer an alternative to costNC. As a result, the model was quite rigid and did not offer a way for those who felt they needed this number to get the information they wanted. Subsequently, I have added the concept of worth to fill this gap.