MADEONEARTH

Report from the world of backyard technology

Photography by Sam Alvar

The Instruments of Invention

Bob Dylan was born in his hometown, but Duluth performance artist Tim Kaiser has a different musical hero: Harry Partch (1901–1974), an underappreciated composer who invented new microtonal scales for instruments he built himself.

“He was a curmudgeon and a brilliant musician who couldn’t stand convention and created his own,” says Kaiser, who also coaxes foreign sounds from far-fetched equipment made by hand.

As a teenage musician, Kaiser discovered a new auditory universe at the University of Minnesota and began assembling avant-garde noisemakers to suit his sonic tastes. His technique? Scrap parts and a junior high school electronics class.

Some 20 years later, Kaiser has made more than 150 instruments, including a stenography keyboard wired with the guts of a mini teaching piano, a green effect box with beehive lenses that loops a 2-second delay, and an old espresso bin called TankPodDrum, fitted with all things pluckable and tappable. Kaiser takes commissions, but saves his favorites for his own live shows.

TankPodDrum’s shell is a hollow, 6"-diameter, 14"-tall stainless steel vessel that Kaiser scored for 70 cents at a salvage yard. In his home studio, he used stove bolts to add a right angle fitting from a hot water heater, brass bells from a rotary phone, a comb of rods from a toy piano, music box tines, bits of chrome, and rack handles. When Kaiser bangs on the attachments with a mallet, the drum acts as a resonator. A pickup epoxied to the barrel’s interior connects to an amp or, if Kaiser is playing, a modulation delay that echoes and fades not only the pitch but also the frequency.

After Partch died, the American Composers Forum inherited the rights to his work and released more than 100 of his recordings on the Innova record label. “I’ve always dreamed of being on Innova,” Kaiser says.

Dreams apparently come true. In June 2007, Kaiser’s latest solo album, Analog, was released on — you guessed it — Innova.

—Megan Mansell Williams

![]() Watch and listen to Tim Kaiser: timkaiser.org

Watch and listen to Tim Kaiser: timkaiser.org

Photograph by Yifeng Song

Sustainable Junkyard Wars

If you happen to live in rural Bolivia, building a water pump isn’t going to include a visit to the local hardware store or being able to plug into a power grid to operate a machine. So how do you get water?

This was the challenge given to Kara Serenius, Hessam Khajeei, Galvin Clancey, and Gaby Wong, a team of students determined to create a safe mechanism for groundwater recovery and hopefully win a prize at the same time.

The team was competing in the first annual Designs for a Sustainable World Challenge, hosted by Engineers Without Borders and the University of British Columbia’s Sustainability Office.

Student teams were asked to create an object to address a social economic challenge, building it in a short time frame and from what could only be described as garbage. Basically, this was akin to an ultra-sustainable episode of Junkyard Wars, with a heavy dose of social responsibility.

The design process for their solution — a human-powered treadle pump — necessitated a serious look at the development challenges in Bolivia, as well as a survey of the available trash you find in a university setting (lumber, metal rods, plastic piping, etc).

A total of 12 teams were armed with a few power tools and given time to plan solutions. Their tasks varied from increasing peanut-processing efficiencies in Bangladesh to devising ways to lower carbon dioxide emissions in China to capturing fresh water from the misty climes of coastal Ireland.

After frantic planning, a fairly detailed schematic of the treadle pump was produced. On the day of the event, six hours of frantic construction culminated in the final creation. In the end, not only did the treadle pump win first prize, but it also generated the loudest cheer when Wong stepped up on the pump and demonstrated that it did, indeed, work.

“The success of the event and the motivation of the students involved are both living proofs of the desire of today’s youth to have a positive impact on the world of tomorrow,” says Yifeng Song, one of the event coordinators. And the possibility of a little more fresh water isn’t bad, either.

—Dave Ng

Photograph by Isabel Blas

Eco-Gym

The modern gymnasium is very much a 19th-century creation, no matter how much the fitness freak is kitted out with bad hair, retro headbands, and spandex, or contemporary embedded LCD interfaces and computer-generated body plans. Gyms harken back to a world of classical mechanical physics, plugged into equations of work and energy.

To the strains of Olivia Newton-John’s aerobics anthem, the puritan work ethic is transformed into a sweatshop for the body beautiful. The slick machines, treadmills, and cross trainers merely serve to disguise antique apparatuses more at home in a world of steam engines, and to stifle enquiry into thermodynamics and economy.

Then there’s artisan Manuel de Arriba Ares. Under the sign of his “eco-gym,” Gimnasio Ecológico Lumen, Arriba has turned the demon of entropy on its head. Making use of the very waste and byproducts of the modern entropic economy, Arriba has created a truly practical monument in the form of a supremely low-tech gymnasium. Its fitness machines, created with a good deal of physical effort over three years from raw and junked materials such as wood, rope, and rubber, directly mirror both the design and functionality of those found within its wasteful counterpart.

Located in the small town of Valdespino de Somoza in the north of Spain, Arriba offers free access for all to this functional work of Art Brut, a wonderful Heath Robinsonesque assemblage constructed from remnants of strollers, boats, bicycles, and automobiles salvaged from neighboring dumps.

Helpful signs, painted on the tarnished white remnants of refrigerators, instruct the would-be eco-gymnast on exercises and operation of the intricate machinery, reflecting Arriba’s knowledge and experience over many years as a physical education teacher.

Lumen is a “gymnasium that was born of the nature, (and which) will return to her,” Arriba philosophizes. The cycle of waste, embodied by so many aspects of the smogged-out city gym, is closed.

—Martin Howse

Photograph by Sally Myers

Real-Life Concept Cars

Like many people of his generation, Baron Margo was dazzled by the futuristic concept cars Detroit trotted out year after year. And, like many people, he was disappointed that those streamlined vehicles remained unobtainable concepts to the average motorist. But unlike many people, Margo did something about it. He, as he describes it, “stepped up.”

He started to build his own cars. Cars that appear to come from a parallel world, one where you debate whether to vacation on the beaches of Venus or go skiing at Olympus Mons on Mars.

I first saw one of Margo’s rocket cars parked at a local diner, a gleaming silver torpedo wedged between unremarkable Corollas and SUVs. Closer inspection showed the work of an incredible craftsman: the sleek aluminum surface was covered with metallic detail, bristling with rivets, lights, and a massive faux jet exhaust with a rotating outer rim.

The three-wheeler uses recognizable parts — a modified front suspension from a VW Beetle, a motorcycle engine — in clever reworkings of proven designs, a practical approach that makes Margo’s vehicles not just beautiful to look at, but also legally roadworthy.

But these quite noticeable cars are just the surface. Margo’s home is a treasure trove of robots, rockets, and intricate machines, made primarily from found scrap, aerospace salvage, and construction remnants from the Glendale Galleria. Standing in one place, you can see a brass-and-steel train, an old Crosley auto, a gigantic robotic dragonfly, a family of upright robots and their android dog, and so much more. It’s dizzying, inspirational, and humbling.

Margo is a reserved man, and while he’s sold some works to the rich and famous and to the movies (rayguns for the Men In Black series), Margo does what he does simply because he loves it.

Margo is a wildly creative man, a dreamer who manages to actually make things real, thanks to a strong sense of the pragmatic, as seen in the two pieces of advice he gave me: “Take the easiest path” and “Don’t burn yourself.” Sage advice for every maker.

—Jason Torchinsky

≫ Baron Margo’s Cars and More: baronmargo.com

Photograph by Bob Halvorsen

On the Wings of a Straw

“I remember walking down the beach, looking at seagull feathers and wishing I had a thousand so I could make a kite,” explains Carl Rankin, a longtime model maker and the man behind several amazing DIY model airplanes.

Rankin’s musings about quills led to explorations with drinking straws, and soon, conjoined with thread, tape, and plastic cling wrap, the Jules Verne model was underway. A marvel to watch, this three-tiered, 56"-wide, radio-controlled airplane is capable of flying at walking speed, a feat more challenging than rapid flight.

Ingenious at finding new uses for common household items, Rankin is always on the lookout for new materials. Skewers, cocktail straws, and paper clips have made their way into his models, and one of his favorite inventions is the use of colorful plastic wrap to cover planes like the Jules Verne. It’s strong, lightweight, and malleable, with the added benefit of lending surfaces a shimmering glow.

Rankin grew up in a “flying family” and enjoyed making model airplanes even as a child. But back then, he fretted that his models didn’t measure up to his brother’s. This worry became fodder for an enduring curiosity about accessible techniques and materials for building, and Rankin has since designed hundreds of models.

In 2004, he handwrote a book about one of them, the Foam and Tape Cub. The instructions are packed with valuable and meticulous details about making models, but they have the charming familiarity of learning from a friend. Made from recycled takeout containers and tape, the plain white surface of the Cub practically begs to be customized. Readers from around the world send Rankin photographs of their own versions of the Cub, from brightly painted or fitted with special wheels to inventive double-Cub biplanes.

Perhaps best of all, unlike expensive store-bought counterparts, homemade model airplanes are durable. As Rankin says, “If they crash, you just tape them back together.”

—Annie Buckley

≫ Carl Rankin’s Model Planes: flyingpuppets.org

Photograph by Rob Carter of Mixed Greens Gallery

Hard Wood

In Lee Stoetzel’s world, Harley-Davidsons, Volkswagen buses, Macintosh computers, and McDonald’s Big Macs all grow on trees. Or at least the materials to make them do.

The Pennsylvania artist recreates iconic products entirely out of wood, with a little steel and Bondo for support. “I stick with very recognizable parts of American culture,” he says.

Stoetzel’s woody representations tie these objects of conspicuous consumption back to the power of nature and the fragility of the Earth. Just don’t call him a hypocrite. All of the wood comes from trees that were already killed by fungus and dredged from rivers. Indeed, it’s the wear of the wood that attracts Stoetzel.

In 2004, he built an exact replica of a 1942 Jeep based on an Italeri model kit. The gouges and scars in the pecky cypress wood reminded him of bullet holes, he says, perfect for a classic military vehicle that has since become the quintessential four-wheel-drive.

There’s also the 1960s counterculture car-of-choice, the VW bus, whose wood doppelgänger is currently parked in his dining room. That one was tough because he based it on his daily driver. “Every time I saw the real bus in my driveway, I’d notice something wrong about the sculpture,” he says.

In the case of Chopper (seen above), the custom “Captain America” Harley-Davidson from the film Easy Rider no longer existed. So Stoetzel started with a small Franklin Mint replica, scaled up with careful caliper work.

Stoetzel’s woodworking chops come on a need-to-know basis. Much of his knowledge was picked up chatting with the “older retired guys” who still put in a few days a week at the woodcraft store where he buys his supplies. The rest comes from the web and DIY books. While constructing the VW, he built his own steam bender from PVC pipe to shape the wood into the bread-loaf shape of the bus.

“After spending two years on the bus, I’m not being as ambitious with scale,” he says. “This week, I’m making a pizza.”

—David Pescovitz

≫ Stoetzel’s Woody Wonders: leestoetzel.com

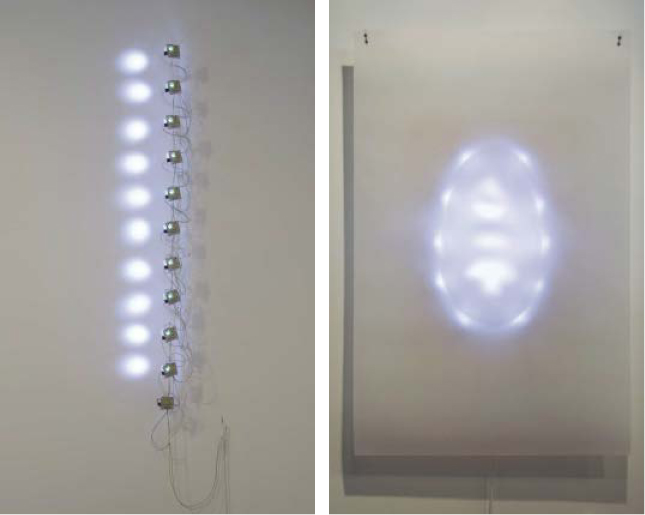

Photograph by Claude Zervas

The Nature of Microcontrollers

A Washington native, Claude Zervas brings his background as a software engineer to a fine art practice using technology and related apparatuses rather than paint and canvas as a medium.

Zervas’ predominant subject matter for the past few years has been the Northwest’s verdant and extreme landscape: dense evergreen forests, glacier-melt rivers, and strange roadside attractions.

In his 2005 sculpture Skagit, a section of the 150-mile-long river is rendered in glowing green cold cathode fluorescent (CCFL) lamps that climb down from the wall, clamber atop a series of thin steel rods, and eventually split into two forks. Wires and inverters splayed on the floor resemble additional tributaries.

Considering the subject matter, the choice of materials might seem an unusual substitute for the real thing. Zervas’ work begs an increasingly important and complex question: what is nature anymore?

In his Forest series of computer animations, “forest” is misleading as parts of the landscape have fallen prey to logging. Clear-cuts and swaths of spindly new-growth trees populate the frame until a single-channel computer algorithm set on a continuous cycle slowly morphs and blots the view from existence. Then the cycle begins anew.

“I’m more interested in the memory associations that arise out of perceptions of landscape,” Zervas says of his work.

The artist has recently gone from the macro of the forest to the micro of marine life. A new series of wall-mounted sculptures uses what Zervas calls “motons” (small circuit boards studded with alternating blinking lights run by a microcontroller) to investigate the phenomenology of simple life forms.

Their movement is so quick that it’s hard to tell anything is happening at all. What the brain registers instead is the space between — similar to how Zervas situates the viewer between dying landscapes and new technology.

—Katie Kurtz

≫ Claude Zervas: claudezervas.com