Maker

HANDS-ON: Engineer Ugo Conti in his home workshop, where he designed the wave-absorbing Proteus, an ocean-crossing boat that sits high above two 100-foot-long inflatable pontoons.

A Feel for Engineering

Ugo Conti’s Proteus boat reflects a unique instinct for design.

Humans have been building ships for thousands of years, but it took a retired engineer working in his garage to figure out a way to span the seas without rocking the boat.

At his hillside home overlooking San Francisco Bay, Ugo Conti designed and built Proteus, a prototype of a radical new class of watercraft that looks like a cross between a common waterbug and an invading spaceship from War of the Worlds.

Called the Wave Adaptive Modular Vessel, or WAM-V, Conti’s innovative design solves a problem that plagues all conventional boats: maintaining a smooth ride while traveling through big waves and pounding surf.

To accomplish that, Proteus is built on a pair of 100-foot-long inflatable pontoons with a cabin suspended by a set of arches 20 feet above the water. The pontoons are articulated and the arches are flexible, so Proteus adapts to the changing contours of the ocean’s surface in much the same way that the independent suspension of a car absorbs big bumps to give passengers an easy ride.

As an added bonus, the WAM-V configuration is also extremely fuel efficient, enabling Proteus to travel 5,000 miles while carrying just 2,000 gallons of onboard fuel. All told, the idea works so well that it has attracted the interest of the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research, which is evaluating Proteus for possible military use.

Superficially, Conti is an unlikely candidate to revolutionize ocean travel. Born in Italy, he emigrated to the United States in 1965 and got a Ph.D. in geophysics and oceanography from the University of California at Berkeley. For much of his professional career he worked as an electronics design engineer, specializing in low-frequency antennas and geophysical instrumentation systems. Along the way he dabbled with boats in his spare time, including several that he built and sailed himself.

Photograph by Robyn Twomey

Now 70 years old, Conti still spends his days building things in his garage workshop, and he remains a hands-on maker. I sat down with him to find out more about the development of the WAM-V and how he learned to solve very old problems in very new ways.

Todd Lappin: What made you decide to become an engineer?

Ugo Conti: I was born an engineer. That’s what I am. The instinct of wanting to understand how things work and using that understanding to do something, to make something — in my case that started at a very early age. I have intuition about how things work. I understand certain simple things, like the laws of physics, for instance, without mathematics. I’m not a mathematician. I don’t do mathematics.

TL: You’re just a very hands-on person?

UC: Yes, absolutely. Learning is extremely difficult for me. It’s not easy to study. I have a hard time remembering things. Then how did I get a Ph.D. at Berkeley? I’m a very normal person, but I have big peaks. It impresses people, because I can approach a problem without knowing anything about it and come up with a solution. It may be a problem people have been working on for months, but I solve it quickly, just out of intuition. It’s a gift. I was born with it. People look at the peaks and think I’m a genius. Well, yes, in the peaks I am, but most of the time I’m just normal. In fact, I make a lot of mistakes. I mean, one mistake after the other.

TL: What was the inspiration for the unusual design of Proteus?

UC: I get seasick. I suffer from motion sickness. When I sailed around the world on a regular big sailing boat, that was a big problem. When an engineer has a problem, he wants to find the solution. He wants to make something to solve that problem. The problem was motion. At sea, motion is a problem. And it’s not a problem only for motion sickness, but also for stability, for safety, for all sorts of things.

Also, I think if you go down deeper, I’m motivated to do something that doesn’t exist. There’s an attraction to that. I’m not copying something; I’m doing something completely new. That’s how I ended up in the boat business, even though I’m not a professional boat builder or designer.

TL: What about the unusual configuration of the WAM-V? Where did that come from?

UC: Originally I was thinking about building a flexible sailboat, with a flexible mast. I always wondered why masts aren’t flexible. That’s how it works on a windsurfer. On a windsurfer, a person uses their body to adjust the position of the mast. The person provides active control and flexibility, because if the wind picks up, you don’t stand stiff and rigid. You adapt automatically because the mast is always pivoting.

Insects and bugs work in a similar way. They not only have great control, but they also go through obstacles very quickly because they’re flexible.

TL: That sounds more like biology than naval architecture.

UC: In fact I studied ants and so on. I was studying insects and how they have many legs. All those legs are controlled and flexible, so it’s OK because you can always keep them where you want.

TL: Those ideas led to the development of your early models?

UC: Yes, I made a model of the boat that eventually became Proteus, and put it on the living room floor. That’s when things started to happen.

I’ve learned that big projects have three stages: fantasy, dream, and plan. The fantasy stage is all in your head, obviously, but eventually you decide you’re ready to get a little bit more real. The dream stage is where you actually start thinking about the project in practical terms. After the dream you start planning. You go into planning and doing, and that’s when reality strikes. You never succeed in fulfilling a fantasy, almost by definition, because it’s just a fantasy. But the fantasy is what catches the imagination and provides motivation.

TL: What was the hardest setback you encountered while building Proteus?

UC: I started this project by building a prototype — a 50-foot prototype I built in the garage.

“The good thing is that if you’re ignorant, you don’t know what cannot be done.”

EASY RIDER: Proteus is a WAM-V boat, a Wave Adaptive Modular Vessel designed with flexible hulls that conform to water surface movement, absorbing the energy in much the same way that an automobile’s suspension cushions the rider (or unmanned payload) from bumps in the road.

Photography by Marine Advanced Research, Inc.

I designed it out of carbon fiber, and we spent a lot of time on it. But on the day we launched the prototype, the carbon fiber broke almost as soon as the boat hit the water. Why? It broke because I didn’t know how to design with carbon fiber. Mistakes. I mean, I make a lot of mistakes. That’s when I decided to forget about carbon fiber and use titanium instead.

TL: That sounds like a nightmare!

UC: Yes, but I once gave a talk entitled “The Role of Ignorance in the Creation of a New Species.” I’m basically an ignorant person who knows very little, because I don’t have a good memory. The good thing, though, is that if you’re ignorant, you don’t know what cannot be done. All my life — professional life, university life, and so on — I always took advantage of that, by not knowing what couldn’t be done. That’s how I’ve been able to think outside of the box. Because I am ignorant, I just start by making or designing things.

TL: What does being an engineer mean to you?

UC: Engineers look for solutions. That’s what engineering is for me. Engineers see something and have a physical thing as a goal. But I am an old-fashioned experimentalist. I put my fingers into electronic circuits to see if they work. I did that for decades, successfully. If something doesn’t work, I kept sticking fingers in until I find out what’s wrong.

TL: So, your approach to making things is very empirical? It’s about just doing it and seeing what happens, learning, making mistakes, then fixing them?

UC: Yes, it’s essential for me to make things physically, but I design in my head. I can think of what to do physically by visualizing something mentally. I see things in 3D, and I can turn them around to feel if they work or not. It’s as if someone were explaining to me, “OK, now I’m going to weld this to that, and this will do that, and oh, that tube is a little bit too small,” and so on. On most days I wake up at 5 o’clock in the morning, and I stay in bed for an hour or more doing that.

TL: Why is the U.S. Navy interested in Proteus?

UC: The Navy is very conservative, but they are interested in adapting the WAM-V for use as an unmanned vehicle. It has a lot of advantages. First of all, it collapses, so you can put it into a box, open it up, throw it in the water, and it’s ready to go. It’s also very difficult to overturn, so it can stand up to bad weather. It’s extremely stable, so it’s a better platform for sensor systems. And it’s scalable.

Proteus Wave Adaptive Modular Vessel (WAM-V)

Length: 100 feet

Beam: 50 feet

Displacement: 12 tons, fully loaded

Payload: 4,000 pounds

Draft: 8 inches forward, 16 inches aft at half load

Fuel: 2,000 gallons

Range: Roughly 5,000 miles

Speed: 30 knots, maximum

Passengers and crew: Berthing for up to 4 people

Materials: Titanium, aluminum, and reinforced fabrics

Cabin: Control bridge and modular sleeping quarters

Pontoons: Inflatable, six-chamber hulls with articulated engine pods

Engines: Two Cummins MerCruiser Diesels, Quantum Series QSB5.9, 355 horsepower each

Transmission: TwinDisc MG-5061 A marine gears with Arneson ASD 8 surface drives

Suspension: Titanium springs

We have a contract to build a 12-foot, unmanned version of the WAM-V. We’re collaborating with Florida Atlantic University. They’re going to do the unmanned systems — the brain — and we’re building the boat — the body — using improvements that we learned from Proteus. We’ll see if the Navy decides to pick it up or not. It may take five years, but that’s fine, because I’m also interested in other things.

TL: What are some of the things you still want to do, apart from working on the WAM-V?

UC: My wife is terrorized. She says, “When you finish this, what do you do? You’ll be bothering me all the time.” I say no, I’ll find something else. I always do.

Well, the next thing that seems to be coming up in my mind is to return to a musical instrument I designed and built during the 1980s. I’ve always liked whistling because it doesn’t require any formal learning. I don’t know music, but I’ve whistled all my life. At a certain point, I designed a whistle synthesizer. It takes the whistle and comes out a different sound — same note, same everything, but different. But that was 30 years ago, so it was all analog and heavy. I plugged it in recently to see if it still works, but it’s not working very well. It’s a rat’s nest of wiring inside, but I don’t have the foggiest idea how to fix it because I never made any circuit diagrams.

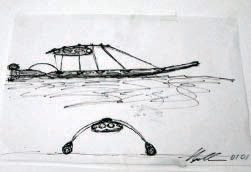

SENILITY AT WORK: Conti spends most of his days in his garage workshop building small models and prototypes of his boats (clockwise from top left): Early conceptual prototypes for the Proteus WAM-V; a flexible pontoon built for Conti’s 12-foot Proteus prototype; Conti’s preliminary sketches for the Proteus reveal the basic shape used in the actual vessel; Conti’s small model of Proteus used flexible, shock-absorbing wires to connect the pontoons to the cabin.

Photography by Todd Lappin and Robyn Twomey (top right)

Now the technology has advanced to a point where it can be made much smaller and faster. I want to develop a modern version of it. It’s basically a software problem, which is something I can’t do, but I can pay somebody to do it, because I know what I want. I want the sounds that come out to be very sophisticated.

TL: That sounds like a great project!

UC: Well, when people ask me why I decided to get into building things like the WAM-V, I blame it on senility. To go really crazy like this, you need to be senile in the sense that when you get older, one of the very few advantages is that you don’t have any more responsibilities. And without much responsibility, you can go off. You can go out of the box. You don’t have to be prudent. That kind of freedom is what allowed me to go crazy with this thing.

![]() For a video of Ugo Conti’s WAM-V in action visit makezine.com/19/ugoconti.

For a video of Ugo Conti’s WAM-V in action visit makezine.com/19/ugoconti.

Todd Lappin is an amateur military vehicle scholar, a product strategist, and a consultant.