5

Communicate Effectively

Job Requirements (continued):

- Knows one's own communication style under pressure and hot buttons.

- Understands body language, voice cues, and power of words.

- Stays cool and manages emotions.

- Does not back away from conflict.

- Realizes that everyone does not communicate in the same way.

- Willing and able to adjust one's communication style to work well with other people.

- Speaks up and escalates when things are wrong.

- Knows when to be quiet, apologize, and listen.

- Can say no professionally and wisely.

- Uses influence and persuasion.

You cannot make the most of your workday if you don't communicate effectively. It's not just that the job requirement list for this chapter is very long. Consider what happened with my communication within less than six minutes when I felt stressed, overwhelmed, and behind in my work: I had a meltdown:

- I sent two tense (with annoyed tone) emails.

- I sent an abrupt text to a friend helping me.

- I left an antagonistic voice mail.

If this isn't an advertisement for effective communication, I don't know what is! This was not only my workday but also the workday of the four people who received my messages. I certainly didn't feel good about my actions and later apologized and explained my poor communication.

In my seminars we talk about how, under the best circumstances, effective communication is so challenging between people who are sending, receiving, and deciphering messages. A simple message of a sentence or two sent can be interpreted in so many ways by the receiver. I demonstrate by saying positive words such as “It's nice to see you today,” but with a low tone, no eye contact, or enthusiasm. The participants in the workshop laugh and respond that they don't believe the actual words that I spoke. However, one or two people might respond that maybe I am not feeling well or have something on my mind. We have so much to be aware of in both sending and in interpreting messages.

And the previous demonstration is face-to-face communication; imagine the possible misunderstandings as we try to interpret what the various senders of emails and texts really mean when all we have are words (and emoticons) on a screen. (And even with emoticons, I sometimes have to stop and figure out the intended meaning.) We can also struggle with voice communication when we don't even have the body language clues to help us figure out the “real” messages going back and forth during conference calls.

So imagine the challenge in today's workplaces where we are often battling to be productive, engaged, and satisfied in the midst of chaos. Even in the dream jobs and workdays, there are expected challenges, the unexpected situations, usually stressed people, conflicts, and work overloads. And even if you don't experience these things, there is a good chance that your managers, coworkers, customers, and family are.

Besides these communication challenges today, effective communication takes time and thought, and these are often priorities/activities that tend to get dropped on tough days. Thorough and useful explanations, real conversations, coaching, and successful delegation all require effective communication skills and time. From both individual contributors and also many managers and leaders I hear:

- I don't have time to spell this out for you.

- I don't have time to talk with you over lunch.

- I don't have time to delegate; it's faster to do it myself.

- You understand what I need and the urgency, right?

There is some good news in the quest for having some control over our workdays: We have a lot of control over our own responses, messages, and interpretations from all the texts, emails, voice mails, calls, meetings, and walk-in communication.

To summarize:

- Work conversations are getting more difficult as conflicts arise more frequently and people are more tired, overwhelmed, and not at their best.

- We all have a story that we need to tell and underlying communication needs.

- It is easy to forget that relationships are of real value—laughing together, coaching, learning, understanding—and are an important part of our workday happiness.

In this chapter instead of focusing on one scenario, let's look at all of them. Each has people who are not communicating effectively, and this in turn negatively impacts workday quality and adds to the chaos.

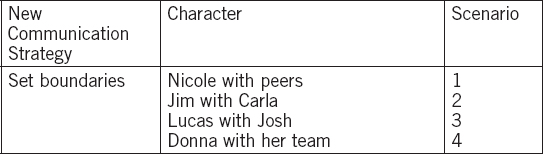

In Scenario 1, Nicole doesn't set boundaries with her peers and allows and even encourages them to come in to chat anytime they want. Her emails can be too direct and interpreted as arrogant.

In Scenario 2, Jim and Carla don't collaborate or listen to each other. Jim doesn't assert himself with Carla and Carla is too aggressive and attacks instead, thinking she is a good communicator because she “says it like it is.”

In Scenario 3, Josh doesn't speak up, ask questions, or push back professionally with suggestions to his boss; he doesn't really listen to people. Lucas doesn't set boundaries by talking with Josh about project concerns and hours spent working around the clock.

In Scenario 4, Donna doesn't say no to repeated interruptions from one of her employees and doesn't delegate to her team. She says yes to her boss when she really means “I won't, but will say yes anyway.” Donna's manager doesn't know how to delegate, which requires clear communication and also active listening.

These characters and their teams all suffer the impacts of their communication styles, patterns, and choices. If you relate to any of the characters, stay tuned for some alternative approaches. Even if you do not relate to the characters, you may recognize your coworkers or managers and gain some insights and ideas about your own responses.

Regardless of your personality, style, generation, motivation, priorities, role, level, or title, effective communication can make or break you. I have seen people from the highest levels in organizations to individual subject matter experts and contributors all struggle to be understood and to understand other people. I have shared with you how under stress, I tossed out all the effective communication guidelines like “Don't press ‘Send’ when you are tired, upset, crabby, or hungry.” If you asked me for the most important skill for today's workday, I would say it is being an effective communicator. The person (whatever the title or role) who masters effective communication has a great advantage both in and outside of the workplace.

Our Needs and Communication

It's important to understand how effective communication is aligned with meeting our needs at work. Most people come to work hoping to do good, interesting work and to have good relationships with coworkers, customers, and their leaders. This positive assumption is one I first heard about in a process improvement class in which the instructor talked about most people not waking up deciding to go to work to cause trouble. The point then, and now, is that often the work processes or lack thereof may be the cause of chaos at work. We also hope that we are compensated as agreed and treated fairly and respectfully. Some also hope for advancement; others may not. Our organizations expect that we will do honest work as assigned and will treat others in the organization with respect.

This may read like common sense or you may be shaking your head as you read this. To be productive, engaged, and satisfied, we are balancing getting work done while dealing with other people. Although this may look superficially simple, we know it is not. This is something I talk about in workshops for managers, but it applies to all of us; we manage our workday balancing the attention to tasks with attention to the people with whom we work to accomplish these tasks. There is no formula I can give you for this balancing act; it's not a clean fifty-fifty split each day. I can share from my own work life that there are some days that are completely task-driven; I've had stretches of work time that are almost 100 percent task-focused with minimal people interaction; however, sooner or later the imbalance catches up with me. I did something radical a few weeks ago: I went with a team member for coffee and we talked about nonwork stuff. I knew this was “right” even though it felt weird. I had been neglecting this kind of human connection and I was struck, over the delicious cold brew and sitting outside, that not only did my team member and I benefit but so would the team and future work. For that hour we were just two people talking and listening to each other about our families, and I knew it was a good workday and that I had been missing this personal connection through conversation.

In Chapter 1 some common needs were presented:

- Wanting to have some control over our work and the workday.

- Needing clear and achievable work expectations.

- Having good work relationships with coworkers and colleagues.

- Having some downtime to refocus, reenergize, and renew.

- Feeling connected and not being alone with our problems.

- Being somewhere between boredom and unhealthy stress at work.

- Being treated fairly and contributing honest results to our organization.

You can see how being a skilled communicator would be necessary to achieve these at work. Let me add four other needs to be discussed within the framework of effective communication:

- We each have a unique story—style, goals, motivation, and preferences—and we bring this story to work. There are times that we need to tell that story and to be heard.

- We have a need to do good work that includes understanding and focusing on priorities and minimizing chaos.

- We need to expect and solve problems either related to tasks, people, or both.

- We need to be willing to really listen to others since other people at work have their own stories to tell.

The tools in the next section are some basics to help build effective communication.

Application Tools: Know Yourself

Chapter 2 was the first strategy section because of its importance as a foundation. It included knowing that our communication style under pressure is critical to a good workday. There is growing time being spent at work resolving disagreements, misunderstandings, and people drama. And, let's be honest, sometimes we bring the drama!

When CPP Incorporated, publishers of the Myers-Briggs Assessment and the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, commissioned a study on workplace conflict, they found that in 2008, U.S. employees spent 2.8 hours per week dealing with conflict. This amounts to approximately $359 billion in paid hours (based on average hourly earnings of $17.95), or the equivalent of 385 million working days. For example, 25 percent of employees said that avoiding conflict led to sickness or absence from work.1

How much time do you spend each day or week dealing with conflict? It would be good to figure out the approximate amount of time that you do spend in dealing with, talking about, and recovering from conflict that goes unmanaged at work. Unresolved and unmanaged conflict takes not only your time but also your energy and focus.

Here are some key things to know:

- Understand conflict is normal. Conflict that is managed effectively can lead to better outcomes; unmanaged conflict can destroy relationships and quality outcomes.

- Know your hot buttons/triggers and how you react to disagreements, bad news, and gossip.

- Know the impact of your reactions/behavior on others.

- Figure out what you need to do to communicate more effectively in times of stress, disagreement, and concern.

Personality tools and other self-assessment tools like the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument provide information that can help you understand how you act under pressure and some alternate behaviors to choose as a strategy when dealing with conflict. When I shot off those two emails and text, I didn't stop to think about my communication; I was just feeling that I was behind and possibly losing trusted help. Instead of waiting before pressing the “Send” button, I just reacted and endangered some good work relationships.

Set Some Boundaries

A basic need for workday productivity, engagement, and satisfaction is to be respected. This need may require us to set boundaries for other people to ensure that we are treated in a civil way that does not demean, insult, or ridicule. That also means that we respect other people's boundaries to ensure that they are treated respectfully.

Some of this is very obvious, and organizations also establish values and beliefs for all to follow. However, as stress and overload grow at work and different work cultures clash—including generational, functional area, gender, and so on—it becomes important to think about setting your own individual boundaries. The workplace or workday chaos is not a free pass to abuse, insult, or ridicule anyone at work. Sometimes, we have to set our own ground rules and realize that other people also have their limits.

I used the word “boundary” as part of effective communication for our basic workday needs. An article by Dana A. Gionta, PhD, and Dan Guerra, PsyD, helps clarify this idea. “What is a boundary, you ask, and why are they important? In essence, a boundary is a limit defining you in relationship to someone or to something. Boundaries can be physical and tangible or emotional and intangible.”2

For the most part we are talking about emotional boundaries, though sometimes there might be a need to establish physical space between you and another person. But often what we see at work are people crossing boundaries of respectful communication by losing their tempers and speaking in ways that are insulting and demeaning.

How Do You Set Boundaries?

You need to be a skilled communicator to identify and set your work boundaries, which means:

- Being assertive.

- Understanding visual, vocal, and verbal communication.

- Listening to learn.

- Having courage and following up.

Here is a simple description of assertive communication: I speak up confidently, managing my emotions to solve problems with other people. I express what I need and listen to what other people need. Some examples of assertive communication include:

- “I need more help than you are giving right now; let's talk about the situation.”

- “I need you to stop calling me names.”

- “I need more detail about what you need/are asking for.”

- “I need you to not talk behind my back and come to me with problems between us.”

- “I need you to stop interrupting me at team meetings.”

The boundary conversation is a good start but does require speaking up if things do not improve or change. We have been discussing individual boundaries, but teams and groups also establish boundaries with ground rules, norms, and guidelines. The challenging part is often following up to discuss adherence to these boundaries. This will take courage to address and the will to follow up. Boundaries will come up again in the strategic communication section: boundaries about work hours, responses to texts on weekends, and taking on new priorities. These situations require more than a boundary rather a professional and strategic problem-solving so that both parties get what they need.

Visual, Vocal, and Verbal Communication

When we communicate face-to-face, there are three components that help us interpret the emotional content of messages: visual, vocal, and verbal. The visual includes gestures, facial expressions, eye contact, and posture; the vocal includes voice tone, rate, and volume. The verbal includes the actual words we say. Effective assertive communication requires using not only assertive words and phrases but also assertive voice and visual components.

Assertive vocal guidelines: An even, moderate tone, rate and volume, with some inflection and expressiveness. Calm, firm, and direct.

Assertive visual guidelines: Confident posture, relaxed expressions, appropriate eye contact, and some gestures that add to the communication.

Assertive verbal guidelines: Words that are clear, specific, expressive, understanding, and helpful to solving problems.

I did not give you an inclusive list; this area of communication may be one that you want to pursue in more depth. I will share that in many of my classes and seminars this is the topic that many people identify as their number-one need. Did you realize that a smile gets a smile? “When I see your facial expression, I get the movement of your face, which drives the same motor response on my face, so a smile gets a smile,” writes David Rock in Your Brain at Work.3

But it is also easy for us to misread each other not only visually but also verbally, especially if we don't know each other very well. I ask people if there is tone in email and usually there is an outcry of “You bet there is!” Think of words on a screen and the ways we either put tone into our message or read/interpret tone where none was intended.

The effective communication I mentioned earlier is not an exact science and requires us to remain neutral and assume positive intentions. That includes remaining open to understanding any generation, cultural, gender, or style differences that impact our interpretation of messages. For example, someone who crosses their arms may be chilly and not closing themselves off to your message or you. A younger coworker may not be unfriendly because they text instead of talking and an older coworker may not be lacking tech-savvy because they prefer to pick up the phone. There is no shortage of communication challenges.

Listening to Learn

Real listening is at risk during tough workdays. You know the reason often used by now: “I don't have enough time!” Let's define real listening as listening to learn, which means paying attention to emotions signaled by visual and vocal components along with hearing the words. And that will take time, focus, and energy.

Here are some other types of listening I have done and witnessed during the workday.

- I listen, ready to pounce when the speaker takes a breath.

- I jab in like a boxer ready to interrupt because I need to tell my story, my side of things.

- I called you back but didn't really want you to pick up.

- I listen and multitask (I think) and glance at my phone, glance away, stand up.

- I give you a listening look but am really thinking about something else (the weekend, the next meeting, how not interested I am in what you are telling me, that you said these things before and I don't believe you).

You might recognize yourself or others in this list or even have other types of listening to add to the list.

However, the rare real listening gets us to problem-solving, improving things, reducing chaos, and repairing or building work relationships. This deeper level of listening is not always possible and necessary during the workday. Here are some things that can help when it is needed.

- Identify situations when you really have to listen, both in reactive and proactive situations and also when the information is very important, complex, or new.

- Know yourself and figure out what is going on when you don't really listen before speaking. What is on your mind? What is bothering you? What is the source of your distraction?

- Tell the person you are distracted and schedule a better time—focus, energy.

- Put aside temptation—your electronic device, thoughts of your next meeting, vacation day, and so on.

- Take notes; choose a listening body language. For example, sit comfortably beside the person, not half turning or glancing away.

If you need to really listen in a virtual meeting, do the same as the above including making decisions about when to not multitask with your phone and to put it out of sight. If you have a one-on-one phone or virtual meeting, that is a time to bring your best listening and engagement.

Real listening is part of being engaged and engaging others at work. Some of you are members of or leading virtual teams over multiple locations and time zones. There are good tools about enhancing communication in virtual work environments. I know from experience that we have to work much harder to engage and communicate well in virtual situations. Some of you are having difficult conversations, coaching, problem-solving, and handling emergencies. Please don't forget to listen, which includes listening to emotions, questions, ideas, and problems you don't want to know about. Not knowing is a false, temporary haven and will only add more chaos down the road.

Challenging workdays require additional tools. You could consider the previous section as the basics and the next section as the advanced. I believe all of the basic tools and advanced tools are required.

Strategic Communication: Tools for Problem-solving

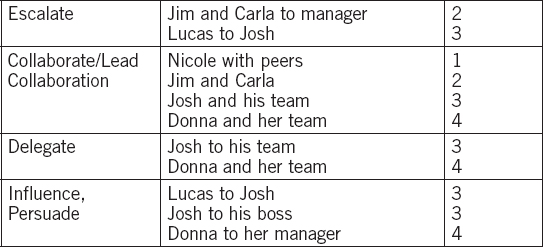

You might look at the following list and have a negative reaction to these words, especially “escalate” and “conflict.” These are strong words, positive in intent, and mandatory to ensure good workdays! I link back to mindset and your possible need to reframe your experiences and beliefs about these action types of communication:

- Escalate.

- Collaborate/lead collaboration to manage conflict.

- Delegate.

- Influence/initiate/persuade.

Escalate

Maybe your think or have the experience in which escalation is a threatening work action. In the context of managing our workdays, I escalate because I care about the work outcomes and the work relationships and believe that there may be jeopardy to both. Escalation is not the blame game or “telling” on someone or covering for yourself. Here, escalation is a positive, professional, problem-solving action.

- I escalate—go for help, involve others—openly, assertively, and letting others know what I am doing and why.

- I escalate when I or we cannot solve the problem on our own.

- My language is professional, positive, and non-blaming but problem-solving.

- I escalate because I care about the mission, customers, team, public, and the organization.

For example: “We have tried to solve this deadline issue between us and it's not working. For the sake of the team, I am going to let Jennifer know that we need some assistance/ideas. I invite you to do the same with Frank.”

Let's use Jim and Carla from Scenario 2 to figure out which of these approaches/choices is most effective.

- Jim goes to the manager alone to complain about Carla.

- Carla goes to the manager alone to complain about Jim.

- Jim and Carla go to the manager together for help.

- Jim lets Carla know he is frustrated and going to talk with their manager, and invites her to do the same.

What a difference an approach/choice makes to the relationships and problem-solving. There are situations when an individual should go talk alone with their manager. I am just suggesting that there may also be opportunities to work it out as a group.

Collaborate/Lead Collaboration to Manage Conflict

What if Carla and Jim in Scenario 2 had looked beyond their individual priorities, assignments, and success and really worked together? Imagine that all the conflict, sarcasm, bad feelings, and discomfort for themselves and their team could have been avoided. I am not saying that I think this is easy to do or that the manager should have taken a hands-off approach, just that they could have taken a different approach.

Effective leaders create a team culture that includes collaboration on all priorities important for the team's success. Effective leaders communicate team priorities along with individual assignments and expect specific collaboration, not some vague request for people to work together and support each other. But since I also know that effective leaders are sometimes in short supply, I question if you need a formal leader/manager to collaborate. I contend from experience that it can be done without formal leadership, but requires an individual or individuals willing to lead without the formal title. Remember: I never said it would be easy.

I hope that in your work experience, you have examples of working on a team that functioned without a formal manager or with minimal leader involvement except when they were needed. I know that leadership is needed especially for communicating clear goals, priorities, and direction; however, I believe that leadership skills, including emotional intelligence and team-building, can belong to anyone. There is a podcast entitled “How to Have an Effective Team Without a Leader”4 that discusses what is needed by the team to be effective working together—with or without a leader—and how important communication is considering the amount of time spent communicating when a team is really working together.

I thought about my experiences as a member of several teams and the required elements for effective and cohesive functioning described in Patrick Lencioni's model: building trust, mastering conflict, achieving commitment, embracing accountability, and focusing on results.5 I shared with you earlier my memories of a small team that worked very hard and achieved good results for our organization in a multiday leadership training event. As I think back I realize that trust built slowly over time and through managing our conflicts, which included testing each other's commitment to the project, delivering on our commitments, working through disagreements and ego, respecting each other's area of expertise, and staying focused on the results. To the credit of the multiple layers of leadership involved, our project vision, goals, and support were clear.

Our first conflicts were uncomfortable, like the first fight with someone that you are in a relationship with. In a good way we were forced to stay together and collaborate because we needed each other. We shared leadership/collaboration, from the project leader to the team members; one of us would always pull us back together. Attacks were minimal and not personal. I was reminded of what Lencioni said about team building: It is heavy lifting.

Delegate

Delegation is a key to productive workdays, engagement, and good management; this process and skill requires effective communication.

Typically, delegation is the leader's or manager's action of transferring the responsibility for a task, ongoing activity, or even larger project to a team member. This delegation can be a regular part of daily work or something intended to be developmental for the individual. Project and team leads also delegate work. There are some practical considerations (time, letting go, and trust) and skills that are part of a successful delegation experience for both the delegator and the delegatee. My focus here is on the communication aspect of delegation and I am going to be radical here and suggest that team members delegate to each other.

Why should we delegate? The simple answer is: to get more things done well by freeing up the person who is delegating and in some cases developing and motivating the person who is delegated to. In Chapter 3, on my six-box matrix tool, delegation was an option following an honest answer to the question “Is this work something someone else could or should do?” And remember the exercise in Chapter 4: “If I had more time, I would....” These questions would be very helpful to scenario managers Josh and Donna. Both had opportunities to delegate to people on their teams, but threw away the opportunity to gain more focus and time along with engaging and developing people.

However, our main focus has been on individual contributors who do not have formal authority over other people, so let's talk about delegation for this person. With support from your leader and a collaborative approach to work, peers could delegate to each other.

There are guidelines for effective delegation regardless of whether you have a manager/supervisor/lead title or not:

- Examine your mindset about delegation and make sure you see delegation as a collaborative tool and not dumping on people.

- Clearly communicate what you are asking the person to do and the importance of the task, timeframe, and any parameter like budget, authority, and so on.

- Follow up, but with the intention to assist if needed, not to micromanage.

- Have the support of your leader if you do not have formal authority.

Your communication skills may be tested to ensure the best outcomes and strong relationships. Especially for team leads and peers, there is a balance needed between being too directive or too apologetic. Nicole from Scenario 1 sent an abrupt and directive email to her peers about their responsibilities for the project she led. Everyone's emotions were already on edge with their manager's sudden departure and all the unknowns that followed. Nicole sprang into action and had her project deadlines and priority validated with the interim executive. I think that talking with her peers about the project would have gone a long way before she sent an email reminding them of their project tasks. Then maybe her actions and email would not have been perceived as something negative by the team.

I am imagining Nicole saying to me, “Mary, I didn't have time for that. I am direct and had to get them focused on my project and shouldn't have to tip-toe around them.” I would agree with her about not having to use time to tip-toe around peers working for the good of the organization. However, I would say that taking time to talk with people before she sent her email about her intentions, especially when emotions are in play, would have been a good use of her time.

Never underestimate the value of effective communication on your workday.

Influence/Initiate/Persuade

An essential skill for a good workday is to know how and when to speak up wisely and professionally in order to influence, initiate, persuade, and even say no at times. I call this “strategic communication” and it is mandatory for good workdays. What happens under pressure is that people react—leaders, coworkers, customers—and reaction often leads to commands, instructions, and/or directions that are given in haste. In a real emergency, this is needed; we want someone to take charge and give instructions.

But for the many situations that are not true emergencies, there will be the need for people to speak up before jumping up. I give an easy model in Chapter 6. To use this model, we will need to initiate, influence, persuade, and even say no.

Situation

Your manager reacts to an executive inquiry/idea about a feedback tool (you don't know if it was a casual idea or a need surfaced from a board member) and tells you to add this tool to a pilot about to go live. Your manager has reacted and you need to stay calm. You know from experience that although it is a good tool, this is not a quick or easy addition; you know this would require quality communication and coordination for which the timeframe doesn't allow. If you are like me, you just really want to say, “No, no way! This will not work! It's too late! What are you thinking?”

Your communication choices

Reactive

- Get upset and argue.

- Try to scramble and rush this new tool into the pilot causing chaos for peers, twenty pilot participants, and about a couple hundred other people.

- Complain to colleagues about this last-minute request and your lack of autonomy.

- Your communication is visibly, vocally, and verbally emotional.

Strategic

- Agree with the positive value of the tool (which you do see).

- Share concerns from a business and customer perspective about rushing this into the pilot and not taking the time to do this well (examples: confidentiality might be at risk; people won't have enough time to respond; a poor first experience will leave a lasting impression).

- Offer the option of putting the tool into the post-pilot future programs.

- Your communication is visibly, vocally, and verbally positive, confident, open, and professional.

Being strategic will not guarantee you the outcomes you think are best, but it will build your leadership and confidence. You spoke up because you cared about the success of the pilot for the people, customers, your manager, and the organization. You are able to see both risks and benefits to the request. You had the courage to speak up in a positive way, offering thoughtful alternatives. Even if the request for the feedback tool remains, you have done your best to be proactive in your response. In situations like this I have “won” some and “lost” some, but I never regretted having the strategic conversation.

In the situation that I gave you, here is some of the strategic language:

- Here is what I/we can do in this timeframe ...

- We could try ...

- I have some concerns about ...

- Help me understand the background on this ...

Think back to times when you may have done this or times when you wish you or others had.

What about saying no and drawing boundaries with bosses? There are times at work when saying no is the right thing to do. However, in the workday situations that we have been talking about, usually saying no as an emotional reaction is not an option. Imagine if Lucas lost it and vented “Look, the team and I are sick of your midnight and weekend messages; I'm not going to respond until Monday!” or “Why did you volunteer us for all this extra work?” I think a break-up would have been a possibility after these communications.

Here are several examples of a strategic communication for Lucas to set some boundaries with Josh for the benefit of them both:

- “Josh, I have a serious issue to talk about with you and need some of your time. After work hours and on the weekend, I focus on my family and get reenergized for the work week ahead. I notice that you send out a lot of emails and texts during that time. Let's come up with a plan so that you and I both get our needs met.”

- “Josh, this is what I can do: read and respond to your messages on Sunday evenings.”

- “How about if you used text for anything urgent only.”

- “I need your time to talk for the project because I see some risks for the customer.”

- “I'm interested in what you are looking for in these meetings.”

Yes, this would take time and preparation but could make the work relationship so much better for everyone.

Choosing the Best Communication Method

The best choice for difficult conversations is still face-to-face communication. Remember those body language clues that can help us communicate effectively. The next best choice is to talk with someone; the tone of our voices can help us to understand meaning and to convey meaning as a way to reinforce the words—concern, interest, enthusiasm, confusion, and so on.

Email is great for one-way communication, but sometimes these messages need follow-up with a call or a meeting to allow dialogue and connection. Before I send what I think may be an unexpected or challenging email, I sometimes call the recipient first to give them a heads-up. Remember that even email may stir up emotions that impact energy and focus.

It is so easy to misunderstand each other, but at least if we are face-to-face, we can see the visual and vocal clues and get back on the right track. With email we see words on a screen and may read a “tone” where none was intended (maybe the receiver is tired or distracted or overly busy). Or if the sender of the message was upset, tired, distracted, or too busy, maybe they deliberately put in a sarcastic, annoyed tone.

Summary

Communication makeover opportunities for scenario people:

Think about the relationship improvements for the scenario characters if they communicated more effectively. Effective communication is a fundamental and critical skill in all of our relationships—one which can add or destroy work production, creativity, quality, and enjoyment. Communication can build, sustain, or chip away at our workday engagement.

The real power of being a skilled communicator will come from our authenticity. If we come from our honest best self with positive intentions along with using techniques, models, and formulas, the possibilities for improvement and change are real. Here are some reminders as we move on to the next chapter:

- Establish boundaries, if needed.

- Your communication with others will impact your workday—for the better or worse.

- Do not avoid the difficult conversations.

- Manage technology; respect others' time/style and use it well.

- Expect conflict and manage it.

- Monitor your real listening skills.

- Get some feedback.

- Review your communication needs and skills, especially the skill of adapting to improve your communication with others.

Reflection and Action

Reflection

- Identify your difficult conversations.

- Think about why these are difficult for you:

- Message.

- Emotions—fear, unease, disapproval, disappointment, dislike.

- Reactions—theirs, yours.

- Put together your list of difficult conversations:

- Pushing back to influence your manager.

- Asking people to meet deadlines.

- Not wanting to be perceived as whining or not perfect.

- Not saying no.

- Wanting to please.

- Standing up to aggressive people.

- Being honest with team members when you don't agree.

Action

- Develop a strategy and language to have one of your difficult conversations.

- Practice with a trusted role model.

- Have the conversation and learn from what went well and what you will do differently next time.