VOICES

As most of you know, many of my films have no voices. For me, the storytelling is in the visuals—my films “25 Ways to Quit Smoking,” “Push Comes to Shove,” “One of Those Days,” all my “Dog” films, “The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger,” and Idiots and Angels were all voiceless.

There are a number of reasons I don’t use dialogue in some of my films:

Reason 1: Films with dialogue are a lot harder to sell in the foreign territories. The cost of subtitling or dubbing is quite expensive, and often that expense will determine whether the film is bought in that territory.

Reason 2: Animating to lip-sync is very slow, difficult, and tedious. It sucks up a lot of energy and time, and it’s not a discipline I enjoy doing.

Reason 3: I’m not a very good dialogue writer. I wish I were, and I hope to get better at it, but I almost flunked English Composition in college.

To me, the image is God. I respond to the visuals, whether it’s a painting or photography or a film. That’s what gets me excited! Visuals are more poetic and speak to the soul. By comparison, words seem to always be explaining things, not carrying the heart of the story. I want to tell a story visually, not verbally.

However, a majority of my films have included dialogue, and I love good dialogue. If an animated film is properly cast and voiced, it’s a joy to hear.

Boy, that’s a tough question. I never really thought of that before.

I guess I would answer it by saying that my preference is to not use dialogue, but if the characters seem to be telling me that they want to talk, then I’ve got to listen to them. I suppose it’s usually the complexity of the story that determines whether I use dialogue. Also, I’ve found that television pretty much demands dialogue; I’ve never seen a TV show that didn’t have words. But maybe I’ll make the first one—who knows?

Also, you may ask why the voices come before the animation. Ever since films have included sound, the voices in animated films have dictated how the characters move and talk. It’s a hell of a lot easier to match the drawings to a voice than to record a voice to match up with a moving mouth. Although the Italians have been very successful in matching dialogue to action, in most Hollywood animated films it’s much easier to have all of the voices recorded before going into animation.

I find my voice actors in many different ways—when I go to the movies, the theater, or comedy clubs, I always make notes of the great voice talent. Also, I use my sound designer as a great resource for good voices. He’ll look at my animatic to find voices that he considers appropriate.

My sound engineer and sound designer work with dozens of voice actors every day, and they have certain favorites that are very talented, professional, and easy to work with. That last one, “easy to work with,” is very important.

I used to use my friends for voices, and although they could do great voices at a party with a few drinks in them, when they got in front of a microphone, they would often freeze up. So it is important to get experienced actors or professionals.

And that brings up the next decision: SAG (Screen Actors Guild) or non-SAG? If you’re working on a big production, with loads of money, then it’s definitely important to work with union actors. They are (usually) famous and will help attract the audience into the theaters.

I did that with my animated feature Hair High, and here is the story behind that film. I was in a bar with my cousin, the great actress Martha Plimpton, commiserating about the lack of success I had with the release of Mutant Aliens. She said that maybe she could make a few calls to her friends and get some big names to do voices in my next feature, Hair High. I said, “Great!” but I wasn’t expecting much.

However, she called me the next week and read off the list of actors she had been able to contact for me: Sarah Silverman, Keith and David Carradine (her father and uncle, respectively), Beverly D’Angelo, Eric Gilliland, Ed Begley, Jr., Peter Jason, and Matthew Perry—wow! I couldn’t believe my luck. I thought Hair High would definitely sell big-time.

At the same time, my office manager, John Holderried, made some phone calls and was able to get in touch with Justin Long and Michael Showalter, who were both eager to get involved too. I booked a sound studio in Los Angeles and another one in New York, and then we started to arrange the paperwork.

Working with SAG was something of a nightmare; a big Hollywood production has lawyers to deal with all the paperwork, but as my studio had only four employees, poor John Holderried had to deal with all of the SAG red tape.

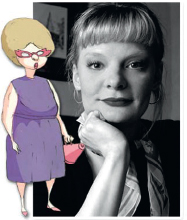

MARTHA PLIMPTON AS MISS CRUMBLES (HAIR HIGH)

The first problem was the SAG rates were too high—they would have broken my budget. SAG has a low-budget agreement for independent films, but it didn’t apply to animation. At first they didn’t believe that anyone could make an animated feature for under $500,000—I guess no one had ever done it before—not using big Hollywood talent, anyway. John had to argue with the formidable bureaucracy at SAG for months to convince them that I could make an animated feature for $200,000 so that we could finally get an indie pay scale.

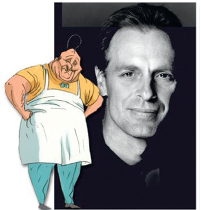

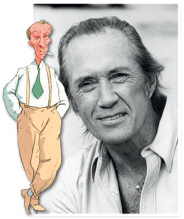

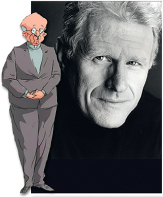

KEITH CARRADINE AS JOJO (HAIR HIGH)

The actors were all willing to take a pay cut because they knew it was a very low-budget film and that I was paying for it out of my own pocket. Fortunately, they all thought it would be fun to do; most of them had never worked in animation before. But SAG almost didn’t sign off on the operation. In the end, they gave us a waiver for each cast member to sign, and Hair High became the first animated feature made under SAG’s lowbudget agreement.

The second problem was the mountain of paperwork: the contracts that needed to be filled out. Forms that asked things like, “Did you search for female Native American voice artists in the casting process?” No, I didn’t have the budget to scour tribal reservations looking for voice talent. Plus, I already knew who I wanted to cast, thanks to Martha.

Third, the day before our final voice-over session in Los Angeles, I got a call from Matthew Perry’s agent, saying that even though Matthew was gung-ho for the project, the agent was afraid that we’d use Matthew’s big name unfairly to promote the film. Uh-oh! I freaked out and called Martha with the bad news, and Martha—brilliant trouper that she is—called her buddy, Dermot Mulroney, who stepped in on one day’s notice.

The great news was that it was a total delight to work with such professionals. I paid them below scale, but they were so committed and dedicated to the job that it was one of the most enjoyable projects I’d ever done. And a lot of that is because of my great friend, Martha Plimpton.

Unfortunately, the fantastic voices never really helped me sell the film. It never got picked up by a distribution company, so in the end I wasn’t really convinced that hiring top-notch voice talent makes a film much more sellable.

After that letdown, I decided to not use voices in my next feature, Idiots and Angels; to my surprise, that film got a much better response than Hair High and did a whole lot better in terms of distribution and sales. Also, the budget was half as large.

Unless I get a big Hollywood contract that allows me to hire big-name stars, I believe I’ll stick with nonunion voice actors when casting my features. It’s just a lot less hassle that way. And when you’re making a film with a small staff, the simpler, the better.

I’ll now describe my procedure for creating voices for one of my films. I’m now casting voices for a new film called “Tiffany,” and there are about 15 speaking roles in the film. (This “Tiffany” project is a very long, serialized feature that’s way beyond my current financial resources. However, if I’m not able to make a sale, I suppose I’ll have to resort to self-financing it over time.)

First, I make a list of the characters with notes about what voice qualities I’m looking for, along with a drawing of each character. Obviously, only a few of the characters are lead roles, and those are the ones that have to be perfectly cast.

In this case, I want to make a short version of the feature film first, as sort of a trailer to help get financing for the feature film. So I choose a small excerpt of the story that would work as a short film that I could enter in film festivals. Ideally, this would get the project some publicity, and I could also use it as an example to show people what the finished feature will look like.

I begin to call some of my usual voice actors—people I’ve worked with and had good experiences with and people who I think are appropriate for the job. I also call my sound designers for recommendations. I bring some of them into my studio for auditions to see how they might fit with my idea for the character.

I give them a page from the script and a drawing of their character, and then I sit with each actor and discuss the personality of the character and the feeling I want. I’ll maybe even try to mimic the voice myself—although I’m terrible at doing voices—or I’ll think of a famous actor’s voice that they can use as a model.

It’s really important for me to close my eyes and imagine my animated character with each actor’s voice as they are reading their lines. Often, watching the actor read is very distracting, and the actor’s appearance has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of their voice.

When I find an actor I like, I ask the actor if he or she would like to do a scratch (rough) reading of all of the character’s lines for my pilot short. This way, I can see how the actor’s voice will work with the animated character, and I can edit this pilot together to try and raise funds for the film.

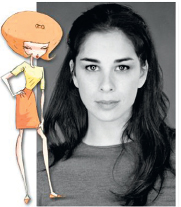

SARAH SILVERMAN AS CHERI (HAIR HIGH)

I usually offer the (non-SAG) voice actors around $100 for an hour’s recording, and they usually accept, for a number of reasons:

1. It’s great experience.

2. They can put on their resume that they worked with Bill Plympton (I know that sounds like I’m bragging, but the actors usually tell me that this helps them).

3. Who knows: this project could turn into the next Simpsons, and they could be walking on Easy Street for the rest of their life.

DAVID CARRADINE AS MR. SNERZ (HAIR HIGH)

For the pilot film, I usually record in my studio, and we use the microphone I have there. It’s a lot easier (and cheaper) than going to a studio, and it sounds quite good. If the pilot is a hit, which I hope it is, I’ll call my sound designer and ask him to set up a voice-record session, booking a studio for two or three days so that we have enough time to record all of the actors.

There are a number of things I look for in a sound engineer. Obviously, the sound engineer must have a good ear. He or she must be inventive: sometimes, the craziest sound works the best. Sound engineers should have a sense of humor, not only because of my work, but because often when there is a problem, tensions can rise and tempers can flare; in these situations, you need someone cool and professional.

Sound engineers should be technically proficient with all of the digital programs and technology involved in recording. Finally, they should know my work and understand what I’m trying to do, and they should also be easy to work with.

As for the sound studio, I don’t want a big expensive studio with a bunch of pinball machines, a game room, and a full buffet for the actors. These studios are for advertising agency clients and big Hollywood films. I’m drawn to the simple padded sound rooms with two or three microphones, script stands, and a video screen so that the actors can see the animatic or pencil test as they read their lines.

After we do a few simple rehearsals, then we usually move into the recording booth and record about four or five takes of each line. Usually the last one is the keeper. I mark that one as my “select,” and we move on. I’ve found that if you do more than ten takes of a line, the entire meaning of the words can get lost, everyone gets frustrated and tired, and it becomes an exercise in futility.

I usually record the actors separately; I rarely do recordings in tandem, because often there is bleed-over. In other words, one microphone can pick up the other actor’s voice, and then it’s not a clean reading. However, if I’m recording a crowd or a group conversation, or if I’m recording a song, then it’s good to have more than one microphone.

One last bit of advice: record the actors on video while they’re reading their lines, for a few good reasons. For one thing, I use this as reference footage; it helps when I’m animating to be able to see how the actors moved and gestured when acting out the dialogue. Also, when putting the DVD together, it’s very interesting to include footage from the voice-over sessions as an extra feature.

For the DVD release of Hair High, we included footage from Ed Begley, Jr. (hilarious), and Sarah Silverman (wonderful) and they really helped to make the DVD a collector’s item.

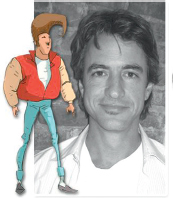

DERMOT MULRONEY AS ROD (HAIR HIGH)

ED BEGLEY, JR., AS REVEREND SIDNEY CHEDDAR (HAIR HIGH)

SARAH SILVERMAN AND ME AT A SOUND SESSION