STORYTELLING

–CLINT EASTWOOD

I’ve been accused of making strange films with weak stories. The critics sometimes say that my stories ramble, and have no focus—that they have too many diversions. There may be some truth to their criticisms, but for me, story isn’t the end-all and be-all in the success of a film.

How many times have you heard the expression “all great films start with a great story”? Talk about clichés! Well, I’m sick and tired of hearing that bull. Sure, there are wonderful films that are great because of the story, but please, give me a break! First of all, people describe great film as “cinematic.” What does it mean? It means it’s a visual experience, something that has nothing to do with words. In fact, I love many films that have either no words or very minimal script—for example, Jacques Tati films, “The Triplets of Belleville,” Georges Méliès, Josef von Sternberg, Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Busby Berkeley. And the films of the Marx Brothers or W. C. Fields, for example, are essentially plotless; they are cavalcades of gag sequences strung together by a weak plot. Or take John Cassavetes, whose films were essentially improvised in front of the camera.

And what the hell was the story for such classics as 2001: A Space Odyssey or Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke or Howl’s Moving Castle? Did you understand anything in these films? Some other great films that have no real story: Citizen Kane (very cinematic) or Woodstock. Yellow Submarine, the animated classic, was begun without a script.

I could go on and on, but why beat a dead script? If I hear someone use the expression “story is everything” one more time, I’ll stick his or her tongue in my electric pencil sharpener—now that’s cinematic!

Having said that, I’m trying with each film to get a better, more emotional story. I believe that Idiots and Angels came close to achieving a very strong story—and certainly in all of my future films, I want to have the most powerful stories possible.

Many of my decisions are made by intuition. Intuition is a very important talent to bring to filmmaking, and I consider it a result of watching a lot of films and being aware of how the audience reacts. Over the years, this experience has become second nature, and it helps me construct my stories.

When I was younger, I’d watch up to eight films in a day—and that’s not counting shorts. I did that for two reasons: first, I’d decided that if I really wanted to be a filmmaker, I’d have to study all of the films, present and past, to see what’s possible and what’s impossible and what works and what doesn’t work. Second, I just plain love to watch movies, good and bad. In fact, I would sit in the front row of the theater so that I could be enveloped into the film. I became part of the luminous screen.

I bring this up because once you’ve made a film, you have to use a lot of self-criticism throughout the process—especially in the story writing phase. And even though it’s impossible to remember every scene of every film I’ve seen, I believe that the stored information gives me a strong intuitive sense of what works and what doesn’t. After watching so many films in the big multiplexes, I can almost know when a joke is going to make people laugh and when it isn’t.

So that’s why I recommend that young filmmakers see as many films as possible. The films that are special and particularly powerful should be seen numerous times and studied and analyzed as to why they work and how they can apply those lessons in the making of their own films.

It’s my feeling that a story’s flow should resemble a great piece of music or perhaps the sex act. Initially, it’s important to attract the attention of the audience, or the “lover.” So I prefer to open a film with something very intriguing or dramatic, just to make sure that the audience is involved. This is the flirtation stage.

Then, as in the act of lovemaking, I like to have short but powerful buildups that end in small climaxes, sort of like acts or sequences, but I follow each scene with an even more intense sequence that ratchets up the emotional involvement—so the excitement builds and builds until the final act, which ends in an explosion of sound, fury, sexual fulfillment, and emotional climax. Not all of my films follow this formula, but I try to keep to it as much as possible.

Another key ingredient in a successful story is having a unique idea. As the Monty Python tagline used to say, “And now for something completely different.”

My films are often not very successful, perhaps because they are too strange or off-beat. But I’d rather see a different kind of film done badly than a clichéd film done very well. If I have a failure, I want it to be a glorious failure.

I look for the off-beat. It’s like when I’m walking down the street. I don’t look at all the normal people; my eye is attracted to people who are strange, bizarre, or out of the ordinary—and it’s the same way with films. I’m on this earth for a short time; I don’t want to create films that conform to the status quo. I want to make art that insults the status quo, that makes people think differently. If I’m in an elevator and everyone has their arms crossed, then I feel compelled to uncross my arms.

A lot of critics call me politically incorrect—well, that’s the way I’ve been since my college days, and it’s too late for me to change now. I’ll never get rich, but at least I’ll have a lot of fun making my films.

“As a producer, be a rational adult. As a director, be a crazy spoiled child.”

—BILL PLYMPTON

Another very important ingredient in a film’s story is conflict. A number of years ago, when Dustin Hoffman won an Academy Award (I believe it was for Kramer vs. Kramer), during his acceptance speech, he went on a rant about how impossible it was to give awards to actors. I’m paraphrasing here, but it was something like, “This actor is not better than that actor. And that performance is not better than so and so’s performance. It’s absurd to give only one award; all the actors should get an Oscar.”

Well, it was certainly a well-meant and very democratic outburst, but I believe Dustin missed the whole point of the Oscars. Who the hell’s going to watch the Academy Awards if everyone gets a damn prize? No one! That’s like the Special Olympics for the handicapped, where everyone gets a prize—and who watches that? People watch only because there’s a winner and a loser. Lots of losers, and that’s good for ratings. That gives the awards a conflict. It’s a contest, like a sporting event. What’s more exciting to watch, a baseball game that ends with a score of 20–0, or one that’s 21–20?

People are attracted to conflict. And the more competitive the conflict, the more exciting it is. I like to build up all levels of a film’s conflicts, so that they culminate or resolve themselves in the last five minutes of the film.

When I was making “The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger,” I was also teaching a select class, the Bill Plympton School of Animation, and I used the making of the film as an instructional tool. I had storyboarded the short, and I thought that the story was pretty strong, but when I put together the pencil test, the ending just sat there, like a wet noodle—the resolution was a failure.

And the class agreed that my ending totally sucked. I thought, let’s go back to the beginning and see if we can bring something from the beginning full circle in the end. Someone in the class loved the idea of the mama cow coming back in the end. That totally resolved the ending—this young calf who loved his mother, rebelled, and got into big trouble was saved by his ever-loving mother. Ah, the power of a mother’s love is the strongest force in the world! So there was the conflict not only with the butchers, but with his mother.

The mother coming back at the end also indicated that the story was over. The fable was complete, and the audience felt that every conflict in the film had come full circle and was resolved.

A great ending can save a bad film, but a boring ending can ruin a good film. I think that’s because it’s the last thing you remember about a film, so you walk out of the cinema thinking, “Wow, what a cool ending!” and not “What a mediocre film!”

I asked some of my great animator friends to list for me the most important elements for a successful film, and here’s what they said.

Don Hertzfeldt (“Rejected”, “Billy’s Balloon”)

“The film needs to be honest. Not just a project to get a three-picture deal from Hollywood. It should be from the heart.”

“REJECTED” BY DON HERTZFELDT, 2000

Peter Lord (Aardman’s Chicken Run):

“1. A well-developed bad character. 2. Surprising story points. 3. An ironic idea for a plot (example: a chicken breaking out of a POW camp). 4. A deeply-flawed hero.”

Pat Smith (“Mask”, “Delivery”)

“Have a good ending. The best way to end a film is to simply give the main character what he or she wanted all along, but not in the way he/she could ever foresee. A solid ending will make your film very memorable, whereas a poor ending can ruin even the best imagery and story leading up to it.

“MASK” BY PAT SMITH, 2011

Make all your ideas as simple as possible, and try to keep films short in length. Simplicity is king. All great things are simple. Expressing a simple idea/story will give you more time to concentrate on emotion, character, and technique. The story itself can hold you down if you allow it to boss you around.

Feel what you’re animating. If you can feel it, you will be able to animate it well. Feel it stick, hit, slide, crack, stretch, etc. By feeling what you’re animating, you will be able to capture the emotion and timing … I’m talking about becoming the material you are creating. For example, right now, if I were to become a bomb, I would hunch down, put my hands in front of me like I’m mimicking a sphere … I would begin to shake as I feel the explosion coming. I would suck in slightly as to feel the anticipation, and BOOOOM! I would leap up as if all my guts were being sprayed across the walls!!! If you can do that, you will be a lot closer to capturing it when you animate it.

Concentrate on what comes before and after the action. The motion of a character before he or she performs the action is more important than the action itself. This is why the principle of anticipation is so vital to movement. Also, what happens directly after the action is also vital. Every action needs to be set up; the audience needs to be aware of the reason the character is taking the action, and they also need to know the thought process and emotions behind the reason. Put it this way: the way you throw a ball is not decided by the actual throw itself, but by the anticipation and setup of that throw.

Slow down and use subtle actions. Life is slower than you think, especially when it comes to acting. The audience needs time to see the character think. The most important actions aren’t actions at all; they are thoughts. So slow down, use blinks, use small actions and motions that we do when we are in thought. Do we smack our lips before we drink? Do we let out a big sigh directly prior to making a decision? Be creative, act it out, take note of the smaller subtle actions you find yourself doing.”

That’s a very important question! There are a number of very obvious answers:

1. Myself

2. The distributors and acquisition people

3. The critics/judges

4. The festivals

5. My friends and family

6. Posterity

7. The audience

All of these answers are good ones, and to a certain extent, I make my films for all those on the list. But if you really want to know, the most important for me are #1 and #7.

Certainly, I need to sell my film—I need the money to keep making more films.

The critics are very important to the success of a film; a great review in Variety or the New York Times is extremely helpful for the success of a film. And the festivals are, for me, the first important stepping stone to getting the film out to the audiences. Of course, winning a major festival prize or getting an Oscar nomination is exceedingly important for a film’s success, but that’s not my ultimate goal.

I always love it when my friends and family like what I create. However, quite frankly, there are times when my family doesn’t enjoy, appreciate, or understand my work.

I hope that my films have a long shelf life and that 100 years from now, people will still love and find humor in my work. But the two goals that dominate my need to make these films are to please myself and to please the audience.

Early in my animation career, I was obsessed with getting huge laughs and huge applause for my animated cartoons, so I would stick as many jokes as I possibly could into each film, theoretically to maximize the laughter quotient—the audience was god!

But as I matured, I found that when I put more of my own personality and emotion into a film, it becomes a more powerful film. So, to answer the original question, I’d say I make my film 50 percent for myself and 50 percent for the audience.

My friend, great Oregon poet Walt Curtis, once said to me, “Creating great work is what’s important.” I now think that’s a very powerful statement. Don’t worry about press, critics, film distributors, judges, agents, festivals, family, and friends. If you concentrate your energies on the work, people will discover it.

If you’ve read my Dogma list, you know how humor is one of the key elements to my success.

“A day without laughter is a day wasted.”

–CHARLIE CHAPLIN

Not only is laughter good for your soul and spirit; it’s great for your body as well. Exercising the facial muscles that produce smiles keeps your face looking young. It’s proven that laughter can cure cancer (check out Norman Cousin’s 1979 book Anatomy of an Illness) and even help you live longer. In fact, morose people who don’t watch cartoons tend to die at a very young age. Those are some of the reasons I like to write stories that result in a laughing audience. In fact, there’s nothing cooler for me than sitting in the cinema when an audience breaks out in laughter from one of my films—I can witness everyone turning younger right before my eyes.

As I listen to people laugh, I feel a certain power over the audience—it’s a god-like power that must be similar to what a great musician feels or an actor giving a great performance feels; they have the audience in their hands. But I feel like I’m making the world into children again. I’m the living embodiment of the Fountain of Youth.

They say that dying is easy, but making people laugh is hard. Therefore, I suffer fools … gladly. Really, I like to hear what fools say, because that may lead to a great bit of comedy.

In my humble opinion, it all comes down to surrealism. People laugh when something happens that is a surprise, unexplained, or preposterous. But it has to be absurdly surreal.

I’ll use my Guard Dog shorts as an example. The poor dog is always frustrated by his attempts to find a companion or master, and obviously he always fails. For the humor to work, he has to fail miserably and completely. But it’s the surprise and shock of how he fails, especially when it’s so extreme and outrageous, that makes the films funny. The more absurd the contrast—the more shocking and unreal—the funnier it is. If it were an everyday kind of rejection, then it wouldn’t be funny; it would become a sad drama, instead. But if it’s totally crazy and bizarre, then we laugh.

Someone told me a story they’d heard about a Brazilian couple who came to New York to spend their honeymoon at the famous Plaza Hotel. They were so happy to be at the prestigious hotel that they began to bounce on the fancy bed like it was a trampoline. But they lost their balance and fell out of the penthouse window to their deaths below.

Now, that’s a tragic story, but I couldn’t help but laugh. Why was I laughing? It’s a terrible tragedy, but the absurdity and surprise of the complete joy and happiness suddenly turning to fear and death is one of the hallmarks of great humor.

This phenomenon is true not just for cartoons, but also for writing. The only type of humor I can think of where surrealism doesn’t come into play is puns, but I never thought that puns were all that funny anyway.

You’ll notice that a lot of my jokes are set up using clichés. In most storytelling, clichés are evil, but in humor, they’re golden. I learned this fact when I began my political strip, Plympton. The more common clichés were famous paintings, like Edward Munch’s The Scream, which I used a lot because they were very eye-catching and already somewhat humorous.

So a great source of humor is found in clichés, but the really fresh humor is found in new clichés. I discovered that the concept of your life flashing before your eyes just before you die was an international cliché—I had thought it was just a weird concept shared by a large number of people.

EXAMPLE OF A CARTOON USING THE CLICHÉ OF CYCLONES ALWAYS HITTING TRAILER PARKS

So I decided to make a gag cartoon out of that in a short film called “Sex and Violence,” where a guy can’t find his car keys. He looks everywhere and can’t remember where he lost them. He decides that the only way to find them is to commit suicide, so his life will replay itself and he’ll see where he last put his keys. Sure enough, the short gag was funny all over the world, as the cliché was universal. That’s the kind of cliché that can lead to a great joke.

“SEX AND VIOLENCE” SEGMENT, “THE LOST KEY”, 1999

Another great source of humor is taking clichés and reversing them. For example, instead of a guy slipping on a banana peel, what about a banana slipping on a guy? Or, instead of a dog peeing on a fire hydrant, the hydrant pours water on the dog. You get the idea. There are hundreds of these ideas out there, waiting to be discovered, and the weirdest and most preposterous ideas will be the funniest.

I also like using clichés in my film titles. “The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger” plays on the cliché of all cows ending up at McDonald’s.

VISUAL JUXTAPOSITION, UNPUBLISHED ILLUSTRATION, PEN AND INK, 1980

Another great category of humor is juxtaposition—in other words, slapping together two very contradictory elements. I’m sure you can think of dozens of clichéd or contradictory titles, such as “Why Hugh Hefner Can’t Get Laid,” “Auschwitz: The Happy Times,” or even “Santa: The Fascist Years.”

One great example of contradiction, of course, is Neil Simon’s play The Odd Couple, which is about two men who have absolutely different lifestyles trying to live together. Or something like The Beverly Hillbillies, with country yokels living among very rich and cultured neighbors. Or, conversely, Green Acres, with rich snobs living on a farm.

I use this setup a lot; for example, in Idiots and Angels, an idiot guy becomes his opposite, an angel, so the conflict and contrast appears on the same guy, which opens up the story to lots of possibilities for humor.

Another rich vein of comedy is exaggeration: taking a gag and pushing it to the limits of believability. There’s a lot more humor to something if you keep stretching it to these limits, which is what makes animation so great: the ability to really push for the edge. For example, in my short film “Push Comes to Shove,” two guys are having a fight and each is trying to harm the other. It was inspired by an old Laurel and Hardy routine, very deadpan, in which one of them would take an egg, lift the other one’s hat, smash the egg on the top of his head, and replace the hat with nary a blink of the eye.

“PUSH COMES TO SHOVE”, 1991

Well, I loved that routine, and I wondered what would happen if I took that concept and pushed it to the very extremes of personal pain and beyond. For example, one gag starts with one of the men stringing a rope through all of his opponent’s facial orifices and then tying the rope to the bumper of an off-screen car. As the car takes off, we see that a large boulder was strapped to the rope off-screen, and the rock must now pass through every orifice in his head. Not a pleasant experience, but terrifically funny.

The capper to the funny bit is that the guy reacts with zero pain or emotion, making the gag doubly surreal and absurd. It’s so exaggerated that it becomes impossible—but you just saw it—so you’re forced into great amounts of laughter, I hope.

A lot of writers claim that Disney invented character animation—in other words, cartoon characters that are full of dimension and personality. The so-called beginning point would be the seven dwarves in Snow White.

I disagree. I believe Winsor McCay’s “Gertie the Dinosaur” was a fully developed, multidimensional character decades before Disney started infusing his characters with deeper personalities.

For many years, I was criticized for the lack of depth in my characters and for the perception that humor is more important to me than full personality development. Only over the last few years have I started to take more care to show multiple sides to the personages in my films. My first real experience in working on a film with more sensitivity and character development was when the great TV writer Dan O’shannon (Frasier, Modern Family) asked me to direct a wonderful story he’d written called “The Fan and the Flower.” He was extremely helpful by showing me how a good writer can get depths of emotion and sensitivity out of common household objects like a ceiling fan and a houseplant. The clincher was that after every screening, people would rush up to me crying, saying how this film moved them so deeply.

“THE FAN AND THE FLOWER”, BILL PLYMPTON AND DAN O’SHANNON, 2005

I wished I could thank them and tell them it was all my doing. But really, it was the genius of Dan O’shannon that brought out all these emotions. So I said to myself, maybe I should try this scam—what a great and powerful way to make people love my films.

For example, the main character of Idiots and Angels, whom I call “Angel,” is a lot more complicated than my usual animated stars. In fact, I sacrificed a lot of humor and violence to show the deeper sides of his personality.

I also believe that a lot of the success of my Guard Dog series comes from the dilemmas my dog always finds himself in, because people can identify with him. They say to themselves, “I’m similar to that dog, who’s searching for love.”

For those of you who haven’t seen my Guard Dog series: it’s predicated on the simple idea that everyone wants and needs love. This dog, who’s basically an orphaned mutt, wants it so bad that he becomes much too eager to please—so much so that he ends up maiming or killing the object of his affection. In each short, he decides to give 100 percent of his love to someone, but by the end, he’s completely heartbroken and depressed because he loved too much and drove away his lover. Yet he continues his search for a new companion.

It’s great that people respond so well to the Guard Dog. He’s become my Mickey Mouse, and even the simplest emotion or turn of his head evokes sympathy for this put-upon canine, which makes my job as a writer much easier when creating a film.

But just a little side note to my critics and fans: even though I seem to have matured and mellowed with Idiots and Angels and the Guard Dog series, I still hope to go back to my anarchic sex, violence, and gag-oriented films, because I love to make those, and I believe that audiences love to watch them.

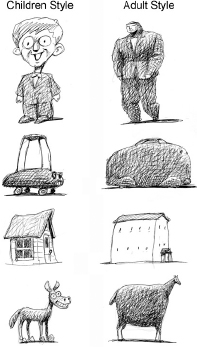

Currently, all of the big money-making animated films are for kids. The big studios—Disney, DreamWorks, Pixar, Blue Sky, and Sony—all make “family” films, and they do a great job of it. So great, in fact, that they’re able to top the box office reports every year.

Now, there’s no way I can compete with those big guys. I don’t have the money, the personnel, or the smarts. If I made a “family” film, I’d be squashed like a bug at the box office. And that’s one of the reasons I decided to gear my films toward adult audiences. It’s a niche that the great Ralph Bakshi pioneered for decades, but now that he’s retired, I hope to take up his place as the premier creator of animation for adults.

Another reason I’ve decided to avoid children’s cartoons is because of my background. Ever since my college days, when I made cartoons for the university’s paper, I’ve wanted to reflect my own thoughts and feelings through my humor.

NOTICE THE SIMILARITIES OF ALL OF THE ADULT DESIGNS VERSUS THE CHILD DESIGNS.

When I moved to New York, most of my survival was dependent on cartoons that I did for all of the adult magazines like Screw, Hustler, Adelina, Penthouse, Cheri, Playboy, and National Lampoon. And I thrived on it, because these were based on my everyday thoughts, not toys, kids playing games, and singing animals. No, I was thinking about love, jealousy, cheating, death, revenge, sex, hatred, and all of the seven deadly sins.

Besides, these topics were much more interesting to me.

I believe that the old refrain “Write what you know” is very true. Well, I’m not a kid, and I don’t have any kids, so why should I make films for kids? I want to make films in which I bring up serious topics in a humorous or wacky way. And I believe that animation is the perfect art form to recreate these darker, deeper stories, because there are no limits in animation. No actors complaining when their heads are cut off or when they have to do impossible action sequences—I like that.

Just so you know, I actually have made films that are appropriate for kids—The Tune, “Gary Guitar,” “12 Tiny Christmas Tales,” “The Fan and the Flower,” and “The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger”—and all of these films were very successful, but still I felt like I had to restrain myself. I had to control my free-spirited ways, and be sure not to offend anyone – which brings me to the next topic.

People often ask me why my films are so full of gratuitous sex and violence. Do you know what the root word for “gratuitous” is? It’s “gratify.” I want to gratify the audience, and I believe that’s what my films supply—gratification.

So I’m proud to have sex and violence in my films. Is it offensive that animation, long the medium of Disney, should also show the naked human body or sensuality? It seems only natural: from Mae West and Betty Boop to Marilyn Monroe and Jessica Rabbit, Americans have always loved sex in their films.

As for violence, let me tell you a little story. One day, I was running to catch a NYC subway train, and I turned my head to check out a movie poster and smacked right into a big steel pillar. The typical New Yorkers standing by saw this and broke into loud laughter. As my face turned red from the impact, I thought, “How could these people be so cold-hearted and find amusement in my pain and misfortune? How rude!”

“GARY GUITAR”, PAINTED CEL, 2006

But then I replayed my accident in my brain, and I thought, “Wow, that was a pretty stupid move on my part. What a dummy I am!” and I started laughing, and the pain in my throbbing head wenta

And that’s what I think happens when people watch my films—the comic violence is so exaggerated and absurd that people laugh at it, and that laughter is a tonic for whatever is bothering you.

Why is it that animation is so popular, yet seems to get no respect from Hollywood? Why is it that everyone knows who the big live-action directors are, but no one can identify the directors of animated films? Yet these films make billions of dollars.

Other than Walt Disney, John Lasseter, and Tim Burton, most animation directors seem to be obscure artists working behind the scenes and making brilliant masterpieces. But that’s okay; eventually, people will realize the true greats of animation.

During the 1990s, I took a little detour to the town of live action and created three features: J. Lyle (1994), Guns on the Clackamas (1995), and Walt Curtis: The Peckerneck Poet (1997). All three were complete disasters.

I think the reason I belly-flopped in live action was that there were certain limitations with live actors that I never had to confront with animation—things like twisting an actor’s head around 360 degrees … SAG has rules about that.

Also, I think my audience preferred for me to stay with animation; they couldn’t accept Bill Plympton as a live-action director. By the way, these films are available on DVD if you want to see them.

The great thing about animation for me is that it fully recreates the bizarre images in my head. Live action can never do that. And I think that people want to see something fresh, something they’ve never seen before. They’re like kids; they like the sense of wonder and unpredictability that can be found only in animation.

Animation is the greatest art form in the world! It rocks!

Censorship versus Self-Censorship

Fortunately, these days censorship is not as big an issue as it was in the past. Thanks to cable and the Internet, there are many more avenues of distribution for work that might offend certain people.

Having said that, I have had a few of my films censored.

When my film The Tune was released by October Films in 1992, I wanted to use a promotional quote from my great friend, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening: “‘The Tune’ would make Bart Simpson laugh his ass off!” Sure enough, the New York Times refused to run the ad in their paper unless we removed the word “ass.”

CENSORED SHOT FROM I MARRIED A STRANGE PERSON, 1997

Another time was when my animated feature I Married a Strange Person was released by Lionsgate Films. This film was probably the most transgressively wacky film I’ve ever made. Blockbuster Video said they wouldn’t sell the film unless I removed four shots from the sex scenes—and even today, when you buy the film on DVD, it’s still the censored version. I do plan to release a Director’s Cut at some point and return the film to its original sleazy form.

But what is really important is self-censorship. I don’t believe it to be a particularly bad thing—in fact, self-censorship is very important for the success of a film.

I did a commercial once for the Oregon Lottery, for a game called BlackJack, in which a man stuck his hand under a lawn mower to retrieve a winning scratch-off ticket that had blown away, and they were afraid that kids all over Oregon would start sticking their hands under mowers, looking for winning lottery tickets. They yanked the spot off the air after just three days.

When I’m looking to distribute my films, I need to identify my audience. So when I write the story or make the storyboards, I keep thinking in the back of my mind about the film’s audience and how they’ll react to things.

And it’s not necessarily the sex or the violence; it can also be about the characters, such as how they react or what they say. I’m always looking to be provocative with my stories, but if they turn people off, then they’re not going to be successful. So it’s a form of self-censorship.

YANKED OREGON LOTTERY BLACKJACK AD, 1992