MY HISTORY

My earliest memory of animation—and remember, this was many years ago, and I don’t have a photographic memory—is watching cartoons on TV at the age of 5.

I loved the craziness, the surrealism, and the humor of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Popeye. Then along came the Disney shows—The Wonderful World of Disney and The Mickey Mouse Club. (I was a card-carrying member.)

I’m always amazed at the huge influence Walt Disney has had on our culture. If he had only created Mickey Mouse, that would be huge, but he also pioneered animated features and paved the way for the Pixar, DreamWorks, and Blue Sky films of today. He was also one of the first to show how merchandising can significantly increase a studio’s income.

His studio was the first to move full force into television, at a time when all of the other film studios were deathly afraid of electronic media. And, of course, he was the guy who reinvented and reinvigorated amusement parks. Plus, he knew how to synthesize all of these elements—-TV, films, amusement parks, merchandising—into building a huge brand of cartoons and fantasy. Mr. Walt Disney gets my vote as the greatest entertainer of the twentieth century.

So I would draw from memory all of these cartoon characters that I loved so much. But I never had enough paper, and I was forced to steal old envelopes and typing paper from my folks to draw on.

I remember one time very clearly—I must have been around 7 or 8—when my dad gave me one of those phone notepads that was about 4 × 3 inches because I was always running out of paper. I was so excited! Finally, I could draw everything I wanted and never run out of paper! (There were about 100 sheets in the pad.)

So I started with the simple things—cars, trucks, airplanes, houses, animals, trees—and then I got to people, and I realized that there weren’t enough sheets of paper for all my planned drawings. “Wow,” I thought, “I’m going to need a lot more of these notepads.”

ME AT THE AGE OF 10 WITH MY BIRTHDAY PRESENT, A PAINT SET

A SKETCH OF MY DAD (MADE WHEN I WAS 15)

Finally, my folks realized that this cartoon habit I had was something serious—a phase that I was never going to outgrow—so they figured they might as well use it to keep me out of trouble. They started buying me stuff like an easel, a paint set, a palette, paper, a drawing board, a pencil sharpener, and other supplies.

I was so excited about creating art that I didn’t know which direction would be the best for me. I loved cartoons, so maybe I’d work for Uncle Walt. I loved the Sunday funnies, so maybe I’d be like Charles Schulz of Peanuts fame. I loved spot gags, so maybe I’d do cartoons for the New Yorker, like Charles Addams. I loved drawing cars, so maybe I’d move to Detroit and draw the cars of tomorrow. I loved painting, so maybe I’d move to New York and become a bohemian painter. I loved illustration, so maybe I’d study at the Art Center in Los Angeles and become an illustrator for the Saturday Evening Post, like Norman Rockwell.

Which direction to take my budding art talent? It was a tough decision for a kid, but there were two things that influenced my decision to become an animator.

My folks were very outgoing; they loved to party, and their parties were legendary. Sometimes, late at night when I was supposed to be in bed, I’d sneak up the stairs and spy on the wild party. My dad was usually the center of attention because he was so damn funny.

I marveled at how he was able to keep everyone’s attention with his antics and jokes—wouldn’t it be great if I were able to amuse people like that some day? That would be the best job in the world!

The second event that directed my career happened when I spotted the Preston Blair book Animation in my local department store. I’d never heard of Mr. Blair before, though I’d certainly seen his work on TV (Disney and MGM cartoons), and that book changed my life.

The way he used a pencil to create emotion, movement, and humor in the book showed me how the cartoons I’d seen on TV were made and how anyone who could draw could also make cartoons. Wow—what a revelation! I’d always imagined that Walt Disney drew all the cartoons himself, and there was no way I could replace the great Mr. Disney.

I remember watching a 1941 Disney feature called The Reluctant Dragon on TV in the mid 1950s; included with the film was footage of Robert Benchley going behind the scenes at the studio to see how animated films were made. There they were, right before my eyes: the animators! These are the guys that create the funny drawings! This is what I want to do—that’s the job for me!

And once Mr. Blair’s book showed me those secrets, hot damn: I was going to be an animator! My direction was clear; my goal was set. Next I had to study the greats by watching as many cartoons as possible to see how the magic was created. Even though I lived way out in the country far away from movie cinemas, art galleries, or museums, I took to hoarding anything that had to do with animation. I remember saving a Saturday Evening Post article from the early 1960s about Walt Disney. I bought Bugs Bunny and Donald Duck comics to study the art and stories.

I became a big fan of Charles Addams—I admired how he used people’s pain, death, and suffering as a source of humor. How could he do that? We’re supposed to feel sorry for people in pain. He was the father of so-called sick humor or dark humor that’s so popular in the films and cartoons we see today.

And, of course, the Road Runner cartoons from Warner Bros. took a lot of that dark, violent humor and made me laugh. But it was Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck that made me laugh the most. You can see their jokes and humor reflected in my cartoons.

Certainly, I loved the cartoons of the Fleischer brothers (Popeye, Betty Boop) and Walter Lantz (Woody Woodpecker), but my two biggest influences were Disney Studios (for their art and storytelling) and Warner Bros. (for their anarchic humor).

I grew up in the rural mill town of Oregon City—not a hotbed of culture, so most of my artistic influences came via magazines and TV. But I was cultured enough to become the so-called class artist, which didn’t mean a lot in a school full of blue-collar kids. In fact, many of my teachers made fun of my attempts to draw or tell funny stories.

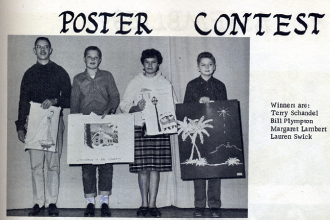

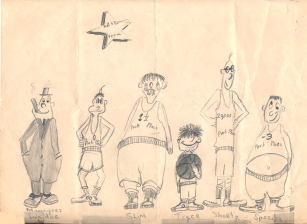

JUNIOR HIGH DRAWING (AGE 13)

I remember one time in art class when I did a woodcut of a sexy cartoon woman, the teacher hated it and gave me an F because it “wasn’t serious art.” Another teacher, in sixth grade, showed a humorous story I wrote to the entire class as an example of what not to write.

It was okay for me to draw cartoons in the school newspaper, but God forbid I should do that during class. I think my teachers were afraid of losing control over the class; their fear of any semblance of anarchy made them come down hard on cartoons and nip the practice in the bud.

Fortunately, I had my dad to look up to, which kept my faith in the power of humor.

I have a very strong memory of an animated short film I saw at the Portland State film screenings. It was called “The Do-It-Yourself Cartoon Kit,” by Bob Godfrey. He was a big influence on Monty Python and Terry Gilliam in particular. But what really impressed me was that this film was not made in Hollywood; it was something called an “independent short.” Wow, you mean you don’t have to work for the big studios? Someone can make a film by themselves? What a concept!

Another powerful influence on my childhood was the natural climate of Oregon’s Willamette Valley. In terms of rainfall, it wasn’t the highest—in fact, we rarely got big rainstorms like the East Coast does—but what we did get was a constant drizzle, day after day, week after week, month after month. It was kind of like those Chinese water tortures—drip, drip, drip on the forehead. Some people say that Oregon’s climate contributes to the highest rates of alcoholism and suicides in the country; I don’t know if that’s true, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it were.

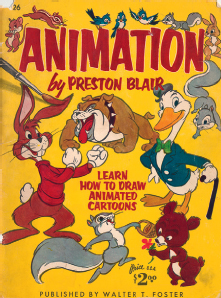

ME, SECOND FROM LEFT, JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL POSTER CONTEST (1959)

However, such weather also forces people to find indoor activities, such as drawing. In fact, there many great cartoonists and animators who hail from the Portland area: Will Vinton, Matt Groening, Brad Bird, John Callahan, Mike Allred, and Basil Wolverton, plus many others. Also there are a lot of psychos from the area—Gary Gilmore, Ted Bundy, and Tonya Harding—so those are your career choices, cartoonist or psycho. I get the best of both worlds: I put psychos in my cartoons.

The constant rain also creates a magical, mystical feeling of nature that is very strong in the Northwest. Walking through the woods, one becomes aware of a mist from low-lying clouds, or a giant fog bank rolling through, and the world becomes very blurry. One sees strange shapes in the distance—is that a man or a monster? A bigfoot? A Loch Ness monster? Or perhaps Tonya Harding?

The imagination is sparked by the fantastic natural phenomena that occur every day in Oregon. Everything is magical; nothing seems real. My brain was caught up in this wonderful fantasy environment.

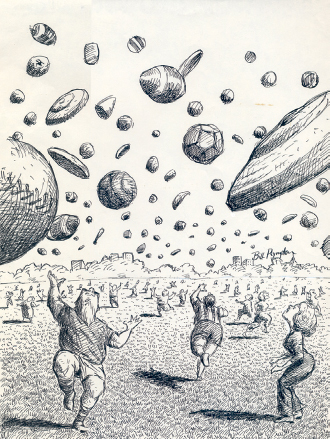

SCHOOL CARTOON (AGE 13)

SCHOOL CARTOON (AGE 14)

SCHOOL CARTOON (AGE 14)

Caption: “YET, HE CERTAINLY HAS FINE FORM!”

CARTOON FOR SCHOOL PAPER (AGE 14)

WATERCOLOR (AGE 15)

SCHOOL CARTOON (AGE 12)

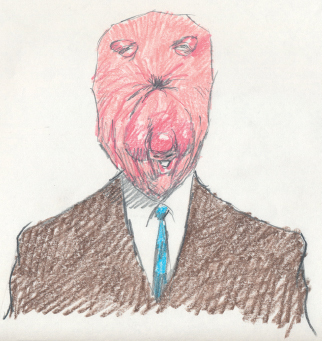

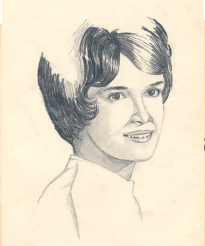

CLASSMATE (AGE 17)

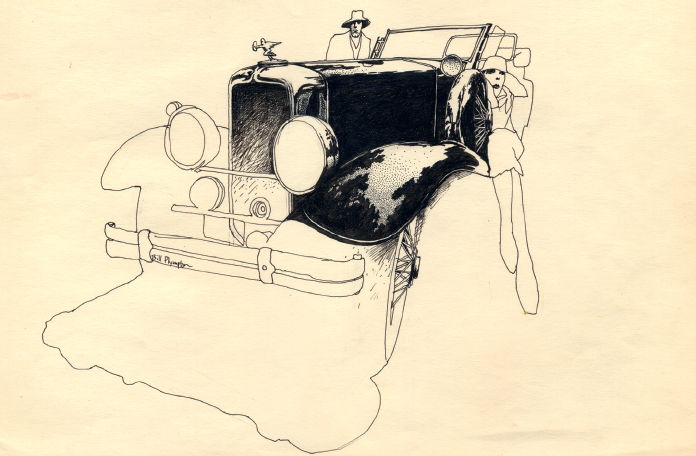

RAPIDOGRAPH (AGE 21)

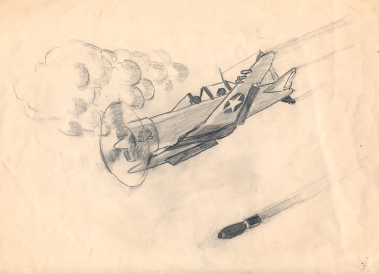

PENCIL DRAWING (AGE 12)

ELVIS CARTOON (AGE 12)

RAPIDOGRAPH DRAWING (AGE 18)

In 1969, I moved to New York City to attend art school at the School of Visual Arts.

Because the animation industry was pretty much in a coma at the time, you can imagine the kind of animation teachers I got back then. One assignment was to make a film using “purple” as the central concept. That was it—that was all the instruction I got. I needed technical knowledge: how to make timing sheets, how to use a field guide, how to use the camera, and how to create sound and music tracks. So much to learn, and all this guy did to inspire me was to tell me to center my film around “purple”! This was in the hippie 1960s.

I remember another assignment, in which I was supposed to take part in some kind of street theater. “In high school, you follow rules,” said the teacher. “In college, you break rules.” So I came to class on the subway one day wearing reading glasses—but these weren’t normal glasses. They had tiny headlights on both sides. I looked like one of those alien mole-people with eyes that glowed in the dark—but blasé New York straphangers all ignored me because they’d seen it all before.

I think that’s when I realized that performance art wasn’t for me.

CENTRAL PARK SKETCH FOR NEW YORKER, 1978 (REJECTED)

The biggest change in moving to New York was being exposed to real culture. At the time, NYC had recently become the center of world culture. All of the famous artists, great orchestras, top music clubs, popular magazines, newspapers, art directors, illustrators, and design studios were based in New York, and I wanted to experience them all.

People like John Cassavetes, R. O. Blechman, Saul Steinberg, Jules Feiffer, David Levine, Tomi Ungerer, Seymour Chwast, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Charles Addams, Ralph Bakshi, Milton Glaser—these were all New Yorkers and people I aspired to be like.

Also, I was finally able to live near a movie theater—and not just one, but hundreds of them, some of which regularly showed art films, indie films, foreign films, and animated films. After growing up in the woods of Oregon, I felt like I had to catch up on 70 years of filmmaking. I wanted to see all of the classic films that I’d heard about, and all of the new hot films coming out, so I’d set aside one day a week to see films, living off popcorn and pop, rushing from one 50¢ cinema to the next, just in time to watch the opening credits.

The Thalia, a wonderful art-house cinema on the Upper West Side, would occasionally screen a monthlong tribute to old cartoons called “Cartoonal Knowledge,” curated by the genius collector and animator Greg Ford.

The great thing about that show was that often he’d program films that were totally unavailable on TV, simply because they were too sexy, racist, violent, off-beat, or just too bizarre for the TV stations’ narrow guidelines. That’s where I really discovered the amazing films of Tex Avery and Bob Clampett, two of my cartoon heroes. Even today, you can see the influence of those two men on my films.

Their work showed me that it’s really important to try different ideas in animation and to get experimental and try to push the limits of people’s expectations and sensibilities—that’s where the best humor lives. But I will talk more about that in later chapters.

I set a schedule for my rise to fame and fortune:

• In my twenties, my plan was to build up my cartoonal knowledge and see every film ever made.

• I figured that in my thirties, I’d develop a killer style that would catapult me to success.

• In my forties, I’d become a household name and get very famous.

• In my fifties, I’d cash in on my famous name and style and become fabulously wealthy.

• Then, in my sixties, I could mellow out by a fabulous beach mansion in the Hamptons and take whatever job appealed to me.

Well, that’s not exactly how it played out—I did develop a style that is uniquely my own and is easily identifiable. However, my other goals fell flat. I’m in my mid-sixties now, still trying to cash in on my talent, and it’s just not happening. The Hamptons beach mansion is a faraway fantasy—basically, I’m barely making it from month to month, just paying my bills, but making the films I want to make.

So why have I never broken into the “big time”? How come I can’t cash in on my unique style and talents? I’ll get to that later on in the book.

As you read in an earlier chapter, the 1970s were a desert as far as great animation was concerned. So as soon as I left art school, I began taking my portfolio around looking for illustration work—but what to put in my portfolio? There was no career in animation, so I was back to the dilemma from my childhood days: what kind of cartoon career did I want—gag cartoons, comic strips, underground comics, illustration, caricature, or political cartoons? Because I was totally broke, I tried to do all of them. Fortunately, it was the Golden Age of Illustration, which eventually ended in the 1990s with the advent of computer technology.

I needed money, and I didn’t care how I got it. But it was all right, because I didn’t really have my own art style—I borrowed a lot from my favorite artists (in fact, I still do), so in those early art days I was looking for both a career and a style.

It wasn’t until 1974, when I started my political cartoon strip Plympton, that I was forced to clarify my art style. As the schedules for a comic strip are often quite short, I had to draw very fast to make my deadlines, so my drawing style became very loose. Also, I had to come up with a funny idea in a matter of minutes, which trained my brain to always be thinking of jokes, and to turn an idea into humor—to find the funniest way to tell a story.

UNPUBLISHED RAPIDOGRAPH ILLUSTRATION, 1978

MY POLITICAL CARTOON STRIP, 1986

I think those two talents that I developed are very important to the success I have today, such as it is.

By the mid 1980s, animation was starting to come back. Also, filmmakers such as Spike Lee and Jim Jarmusch were showing how directors could make their own films without the money or prestige of the Hollywood system. In fact, their movies were better because of the lack of Hollywood’s involvement.

I figured, “Damn, I better make my films now, or it’ll be too late!” I thought that if I waited, I’d be too old to make my childhood dream of being an animator come true.

With very little knowledge of how to make a film, I started making drawings of a man’s face that would transform into bizarre and humorous shapes. And I hired my friend, musical genius Maureen McElheron, to create a song that this head-warping guy could sing—and voilà, she wrote “Your Face.”

Originally, I’d thought of this film as an experiment—to see if I could actually make a film on my own. I wanted to learn the craft, and what better way was there than to just start experimenting?

I remember the first time I showed the film; it was at an ASIFA competition screening in New York in 1986. (I’ll explain ASIFA in a later chapter.) The theater was filled with NYC professionals like R. O. Blechman, George Griffin, Howard Beckerman, and Michael Sporn. I was in the back of the room because I was so embarrassed by my unprofessional, goofball film. But about five seconds in, people started to laugh! I was amazed! My whole body started to glow and shake—this was the laughter I’d never gotten from all of my print cartoons. It was like a drug—I was on a no-chemical high. I needed more; I was hooked!

Afterward, everyone came over to me and asked if I was Bill Plympton. They asked me out for drinks, and I felt like I was home. The next day, I called all of my magazine and newspaper clients and told them I was quitting print. They all thought I was crazy and said things like, “Don’t you know animation is dead?” But I said that I thought I could make a living doing animation.

That goofy little film, “Your Face,” went on to get an Oscar nomination and became a big hit all over the world. I took it to Annecy, the great French animation festival—and after the screening there, many people approached me and offered all kinds of money for the TV and theatrical rights in their respective countries.

“Wa-hoo!” I said to myself. “I’m actually making money on my film! I think I’ll have to make more!” And in quick order, I churned out a string of short animated films that were all big hits: “How to Kiss,” “One of Those Days,” “25 Ways to Quit Smoking,” and “Plymptoons.” I was on my way!

In the mid 1980s, there were three major outlets for animated shorts. The MTV animation department was headed by Abby Terkuhle, who became a big supporter of weird, wild, and funny animation on the channel. He discovered my film “Your Face” at Annecy, and for about ten years, I was the Animation Golden Boy on MTV. My shorts were on Liquid Television (and later Cartoon Sushi), plus I made station IDs for them, promos for the MTV Movie Awards, and a lot of other interstitials. Even today, as I make appearances all over the world, people still remember me as “that MTV animator guy” or “the colored pencil guy.”

Concurrently, there were two very popular theatrical compilation shows touring the United States. The Tournée of Animation, organized by Terry Thoren and Ron Diamond, was the more professional of the two, and I was very honored to have my work included with the best animated shorts from around the world. This traveling show represented the high road to animation distribution.

Taking the low road was Spike & Mike’s Animation Show, which later evolved into Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Show, founded by Spike Decker and (the now-late) Mike Gribble. Their screenings were much more raucous—in fact, it was the closest thing to a cartoon circus.

They wore weird costumes, the audience bounced giant beach balls around, and of course there was Scotty, the Magic Dog. I’d often attend and share the stage with Weird Al Yankovic, John Lasseter, Marv Newland, and of course the crazy Mike Gribble. Those were heady days for animated short filmmakers!

“YOUR FACE,” COLORED PENCIL, 1986