POSTPRODUCTION

BLACK AND WHITE INK-WASH

As you’re probably aware, I began my art career as a print cartoonist, and my love was sequential cartoons. In other words, I drew a lot of six- to nine-panel cartoon stories.

It was via this process that I learned the rudimentary rules of editing—what stays and what goes. What’s important for the story, and what’s not important? I learned about timing, pacing, building momentum, and surprise endings. All of these qualities are important in the process of editing a film.

In fact, when I create my storyboards, which resemble print cartoons, the editing of the film is pretty much predetermined. As opposed to a documentary film, in which only one out of every hundred shots will be used in the finished film, an animated film will probably use about 95 percent of the shots because it’s been so thoroughly planned out.

In this chapter, I will discuss some editing tricks that I’ve learned over the years.

The value of timing is primordial in animation—and even now, I’m still learning how to use timing to my advantage.

I recently saw the wonderful Shane Acker film 9, a stop-motion/computer adventure film. The editing on that film was amazingly fast with a lot of very quick cuts. At times, that technique was quite effective, and other times, I didn’t know what I was watching. Often the cuts were so fast that it was a blur—but it left you with an almost impressionistic feel for the action. You might not be sure what you saw, but whatever it was, it was scary.

But that’s not my style, as I do mostly humor. It’s hard for me to do that kind of quick cutting. I need the jokes to be clear and easily read, so I tend to use much slower pacing—although at times I feel it’s too slow.

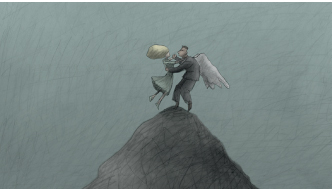

ANGEL ENTERING BAR, FROM IDIOTS AND ANGELS (2008)

There are two good timing examples in Idiots and Angels. One is a scene early in the film, when Angel walks into his bar for the first time. He walks through the door and saunters up to the bar, which is only about four steps away, but I dragged it out to almost one minute of screen time. It must have been about 40 steps—why? I don’t know, it just felt really cool. It was intuitive, the rhythm of the music as it matched his footsteps, the beauty of Larry Campbell’s pedal-steel guitar. It was the whole mystery of him approaching the bar, and the ambiance of the bar itself. So how can a one-minute sequence of a guy walking up to a bar be so entertaining? I can’t really answer that question. All I know is that it’s one of my favorite sequences in the film, and I get a lot of great comments on that scene.

THE DEATH GARAGE, FROM IDIOTS AND ANGELS (2008)

The second scene from Idiots and Angels that has important timing is the sequence in which Angel is driving home, and he parks his car in the garage. Things are going very badly for him at this point: everyone in the bar has made fun of him, and a mad, violent doctor is chasing him. So we see the garage, but Angel doesn’t get out of his car—in fact, he leaves the engine running and closes the garage door. It soon dawns on the audience that he’s going to try to commit suicide. Yet I keep a hold on the garage—it’s one static shot of the garage, for about a minute. Now, again, you think, how can the audience sit still, watching a stupid garage? But it’s the psychological drama that’s going on inside the garage that’s keeping the audience so involved in the shot.

What’s going to happen? Is he going to die? Will someone save him? Will he give up? Then, after I’ve dragged that scenario out as long as I can, I show some toxic fumes seeping out of the garage window—the tension is building, the garage is probably full of exhaust fumes, and he’s certainly done for. He’s offed himself, maybe now he’ll become a real angel—but the tension builds and builds. Remember, it’s still just a picture of a decrepit garage.

I release the tension with Angel diving out of the side window, breaking the glass and coughing and gasping for air as he lays prostrate on the lawn. Wow, that’s so cool! Over a minute of film that just shows a lonely garage! The rest of the story in that shot is developed though minimal sound effects and psychological fear and the imagination of the audience. I wish I could make a whole film like that.

I’ve found that the secret of great timing—especially in cartoons—is to treat the editing like you treat other aspects of a cartoon: exaggerating the tempo, and making a caricature of the timing, if you will. If it’s a suspenseful sequence, you can really slow it down and drag it out. Make the shots longer than real life; make the audience wait. However, if it’s an action sequence, speed it up and use quick cuts to push it to hyper-speed. People love it when you play with their emotions, and editing is a great way to control the audience. The exaggeration of timing can be very enjoyable.

As I stated earlier, conflict is one of the essential ingredients in a great story, and because we’re making a cartoon, we’re lucky in that we can exaggerate the conflict. We can camp it up and make it over the top, and that’s okay, because it’s animation! People expect it.

Let’s say we have a shot of two cowboys with guns drawn in a Mexican standoff. Go ahead and exaggerate the tension-filled moments. Drag them out and use a lot of intercutting between the antagonists—zoom in on their faces, show sweat pouring down their temples, have a close-up of their grinding teeth. Show their hair standing on end, cut to a fist tightening up—it’s animation, so it’s okay! If this sort of thing were done in a live-action film, it would be preposterous—or a Sergio Leone film. But somehow, because it’s a cartoon, it works. The more cuts and cutaways, the more intense the emotion in the film.

ARTWORK FROM MUSIC VIDEO “MEXICAN STANDOFF” (2008)

Another cool thing about computer editing is the varied number of effects available to add style and variety to the film. Before the computer, all of the camera moves and special effects had to be incorporated during the film shoot. But now, with the wide range of visual possibilities available on the computer, a whole variety store of postproduction effects has been opened up.

Let’s go back to the previous shot, in which the two antagonists are staring each other down, ready to have a cowboy smackdown. How about really exaggerating the tension even more with special effects, besides the cutaways, zooms, and alternative POVs? How about dialing up the color extremes—use that bright lime green, or that crazy fluorescent ultraviolet that I warned you about? Or put in some cool shadows. Maybe go black and white and play with the positive and negative—anything to make it out of the ordinary.

Bring up the music; build it up big-time. Recycle it and tilt the images at awkward angles.

I made a film called “Santa: The Fascist Years” in 2008. I came up with the idea in the early 1970s as a Christmas card, but my folks hated the idea, so I stuffed it back into my idea folder and forgot about it. In 2008, I discovered the sketches and realized that now that I’m doing animation, it would make a perfect short.

STILL FROM “SANTA: THE FASCIST YEARS” (2008)

So, over a Thanksgiving weekend, I drew the entire four-minute film. People ask how I was able to make a film in that short of a time period. Well, I cheat—plain and simple. If you examine the film, you’ll notice that there’s not a lot of animation. Instead of laborious animation, I would take two drawings, alternate them on threes, then add a lot of camera effects—shakes, zooms, pans, dust, and scratched-film effects—and for some reason, the audience doesn’t notice the lack of animation because the images are always moving, and it seems like a fully animated short. The film took longer than four days, by the way, to finish. We had to scan, clean, color, and add a voice track (by Matthew Modine) and music, but I think the entire process took about 20 days in total, and it went on to be one of my most successful films.

Editing for comedy is a very delicate talent. I’m not quite sure I’ve really got a grip on it. I’m always studying how others edit for humor—watching and learning. But my favorite example is “Guard Dog.” The film is full of little episodes of the dog imagining all these terrible attacks on his master by innocuous woodland creatures.

My favorite, and also the audience’s favorite, is the bull-in-the-pit gag. Now, I’ve seen it hundreds of times, and I think I know why it’s such a success—it’s the slow, mysterious buildup. In case you haven’t seen it, I’ll lay it out for you.

RAGING BULL SEQUENCE FROM “GUARD DOG” (2004)

The guard dog imagines that this harmless mole digs a humongous pit, then pulls a giant angry bull down into the pit. The fact that this tiny subterranean creature can control a three-ton bull is part of the humor. You acknowledge that it’s building to something, so you accept the crazy premise. That’s funny in itself. And then the extremely energetic mole covers the pit opening with a blanket of grass, and our dog owner comes along and falls into the pit. As he plummets down, he falls into a Ronald McDonald suit that naturally offends the bull. As the shot fades out, the evil mole is laughing its head off to the sound of the bull eviscerating our dog walker guy.

When I storyboarded this sequence, I realized that the setup for the gag was almost as funny as the gag itself, so I timed the mole putting together this fiendish trap quite leisurely, with a lot of little details. This approach builds up the curiosity factor and also the tension. When the trap gets sprung, the punchline hits hard and fast.

It’s that slow, mysterious buildup and quick release that make the joke so funny. It’s actually similar to the Road Runner cartoons in terms of timing and editing.

But I look in two directions for my guidance in timing. First, the old classic comedy films, such as Warner Bros. cartoons, the Marx brothers, and Jacques Tati. After studying a lot of great comics’ timing, I’ve built up a powerful intuition on how to cut a sequence.

The second source of knowledge is revealed when I show the rough cut to test audiences. Sometimes I’ll ask people which gag doesn’t work, and sometimes I’ll get a sense from the quality of the laughter and response what needs to be recut in a film.

I had a number of other gags for “Guard Dog,” and one of them was a particular favorite: a slug with welding goggles sharpening a blade of grass with an electric sander. Then there’d be a cut to him laying a spiral of slime on the newly sharpened grass blades. Our dog owner would get his feet stuck in the sticky slime and fall over on the ground, puncturing his body with the bloody blades of grass.

Now, I thought this was a classic gag—probably the best gag of the film. But no one laughed at it. I even tried to cut it differently, but still no laughs, so out it went. If people don’t like it, out it goes, because I need my films to be a success. I need each gag to be a winner, no matter how much I like a certain joke—if it doesn’t connect, out it goes! But later I can put it in the DVD extras—then maybe they’ll laugh!

ROUGH STORYBOARD OF REJECTED SLUG SEQUENCE FROM “GUARD DOG” (2004)

Another method I use to perfect my editing is watching the film many times—not only with an audience, but also without one. After seeing a sequence played ten times in a row, little imperfections begin to appear, and I know precisely how to recut it.

Sometimes, I have to watch it 30 or 40 times to see where to edit it—I know that sounds incredibly boring, but believe me, when I take my films on tour and I’m stuck watching the same bad cut over and over, each time I want to cut off my fingers with a hot splicer.

Sometimes even a one- or two-frame adjustment can solve all the timing problems in a film. It’s really amazing to me how great editing can make a mediocre film into a great film.

In the early days of my film career, I had very little money to invest in my films. So I hired myself as a sound designer. I rented a Nagra from my good friend, Phil Lee of Full House Sound Studios, and I developed a crude repertoire of my favorite sound effects: footsteps, hitting sounds, sexy kissing, and of course, the ever-popular balloon rubbing sounds. If you listen to my short “Nose Hair,” you’ll hear my sounds (that’s even me playing the guitar on the soundtrack).

But, eventually, because of lack of time and talent, I had to delegate my sound duties to more professional personnel. And boy, am I glad I did. Some of those early films I made sound awful. When you hear the wind blowing, that’s usually me blowing into the microphone—actually, that’s kind of funny in a campy way.

“NOSE HAIR” (1994)

Good sound designers are very rare, and if you can find a good one, someone who can work with an indie budget, you’re very lucky. Hold on to that person for dear life.

There are a number of ways to find these talented people. One is to check out the credits of other films in the short film programs and make notes of the designers who create great sounds. You can ask the director what that person is like to work with and how to contact them. Most directors are very open to helping their crew get other work—and if the sound editor (though they prefer “sound designer”) is too busy, he or she can often recommend someone else.

Film schools are often great places to recruit sound designers, especially if you have a limited budget. Also, if you know what you want and how the sound should be, it’s good to get someone who’s open to direction and other ideas. Often the older designers tend to be a little more set in their ways and less open to suggestions.

I have one horror story to relate—I won’t use his name, because I think he’s still in the business. Anyway, I’d run into this guy occasionally because we had mutual friends, and he kept telling me I was a god, and how much he wanted to work with me—he’d even work for free, just to be able to work on one of my films.

A couple of years ago, my usual sound designer was busy working on a feature, so I called this guy up. I needed a soundtrack really quick to meet a festival deadline, and he said, “Great! Let’s go!”

When I asked, “So, how much do you charge?” he replied, “Don’t worry, it’ll be great!” So I stupidly gave him my project, and after a few days, he played me the soundtrack—and it was terrible. Then he gave me a bill for $1,000, and I said, “What happened to you working for me for free?”

He replied, “Are you crazy? Why would I work for you for free? Nobody works for free!”

The festival deadline was coming up, and he wouldn’t release the soundtrack, bad as it was, without payment in full. I had to pay a ransom to get my film back, but he had me in a desperate situation. I paid the damn money, and then I rehired my usual sound guy later to totally redo the soundtrack.

It was a bitter lesson, but an important one: always get an estimate on the project before you start. I usually like to pay half at the beginning and the rest after completion of the sound mix. It’s very important to get a good sound mix to balance all of the different elements: voices, effects, and music.

The soundtrack for an animated film, short or feature, is very important—I believe it’s even more crucial than for a live-action film. A great sound designer can control the mood and character of an animated film because there is no recorded sound from the set. All of the sounds come from other sources.

Sometimes my drawings are very minimal, even abstract, but a great designer will bring a sense of reality to the film simply by placing some key sound effects. One example is the garage suicide sequence in Idiots and Angels, as previously noted.

I’ve come to the point where I can rely more and more on the sound to tell the story and set the mood, which gives me more freedom to get more creative and stylized with the artwork. Look at my film “Nose Hair,” which has very minimal visuals paired with very realistic sound—that great union makes it work.

It’s the magic union of sound and art that makes the film fly.

A big problem I see (or hear, actually) in a lot of student films is an amateurish soundtrack. Often young students think that to make something funny, they just have to put in a kazoo, or tin whistle, or lots of wacky, crazy sounds. Maybe 70 years ago, when Mickey Mouse first appeared with sound, that sort of thing was hilarious, but not now.

Or a student might appropriate the Hanna-Barbera sound effects library, thinking that’s really cool. No! Perhaps it’s campy, if you want camp, but it only reminds me of unfunny cartoons.

For me to laugh, I need to hear realistic sounds—I have to believe that these are real creatures in a real world. Like I said in an earlier chapter, humor comes when something shocking and unexpected happens to a normal, clichéd situation.

Just like the artwork, the sound should be very conventional—nothing too surprising. In fact, I usually tell my sound designer that he should pretend he’s watching a live-action film and add the appropriate sounds.

As a proud member of the Academy of Motion Pictures, I get to see the other animated shorts that are eligible for Oscar nominations, and I’m always amazed at the sound specs for those films. They’re all Dolby or 5.1 sound (5.1 is the number of channels used for sounds).

Of the 40 or so films screened, mine is usually the only one in non-Dolby stereo. That means that the filmmakers of all of the other eligible shorts have each spent $5,000 or more on their sound system, and $5,000 is the cost of my entire film! Damn, I wish I could spend that kind of money on my sound. However, as I told you earlier, my budgets have to remain low if I’m going to make a profit on my movies.

Besides, I wonder if the general audience can tell the difference between stereo and Dolby stereo. Perhaps they can, but does that diminish the enjoyment or popularity of a film? I’m betting $5,000 that it doesn’t—but you be the judge.

It’s impossible to overestimate the value of great music to an animated film. There’s something so beautiful, and almost religious, about the union of great visuals and the exact, right piece of music.

Some of the classic examples: Fantasia, of course, “The Rabbit of Seville” and “What’s Opera, Doc?” (Bugs Bunny), Yellow Submarine (Beatles), “Feet of Song” by Erica Russell, “The Band Concert” (Mickey Mouse), “Minnie the Moocher” (Cab Calloway and the Fleischer brothers), “Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarves” (Bob Clampett), and American Pop (Ralph Bakshi).

My earliest example is the film “Your Face.” I knew I wanted the guy to sing a song—but what kind of song? I’d worked with Maureen McElheron for years—in the 1970s, I played pedal steel guitar (badly) in her band around clubs and bars in NYC. So when I needed music for the guy to sing, I asked her to pen a song.

Her first composition was haunting and gorgeous, and it probably would have been a hit, except it was too beautiful. The character in “Your Face” was a dork, a square—so I needed him to sing a real cornball-type love song. So we worked together on changing the lyrics, but kept the haunting melody. One line that I really liked—“Your face makes me a happy fella, no more singing a cappella”—was the exact kind of cornball lyrics that I thought the film needed.

At the time, I had no money to hire a male singer, so I hired Maureen to sing the song and play the piano, and we slowed down the track to something like a third of the original speed. And this gave the song a very eerie, nostalgic quality, like it was a song from the 1930s sung by Rudy Vallee.

Believe it or not, the song became a hit. They played it on some New Jersey radio stations, and some people even used it for their wedding promenade song!

AT THE OSCARS IN 1988 WITH MAUREEN MCELHERON

My film Idiots and Angels, being my first feature film without dialogue, required the utmost in musical support. In essence, the music became the dialogue—it would communicate the thoughts and feelings of the characters.

However, looking back on the film, I believe I may have used a bit too much music; in my insecurity, I was compensating for the lack of dialogue.

My process for selecting music is a bit complicated. First, while creating the drawings, I’ll listen to random CDs to get me in the mood. As I travel around the world, people often hand me music that they’ve recorded, in the hopes that I will use it in my films. I like that because I’m always open to hearing new songs and new styles.

Also, if I go to a concert or a club, I often buy the band’s CDs to listen to at home while I draw. I’ve even bought music from NYC street musicians and subway performers, and some of it is quite good and exciting.

As I’m drawing the film, I’ll imagine the music with the completed animated sequence—how would it fit in? Would it enhance or detract from the shot?

When selecting music, don’t just use your music to echo what you’re seeing on the screen. Sometimes it’s more interesting to be ironic. Look for music that’s in contrast to the action you’re seeing—maybe some light, romantic music for a battle scene, or something very heavy and dramatic for a love scene.

In Idiots and Angels, during the violent battle scene with Angel, I played some church choir music that added a nice counterpoint. It brought a lot of spirituality to the sequence. In Hair High, there’s a very brutal football sequence in which players are being massacred on the field of play—I put in a light, airy, romantic French song.

HAIR HIGH (2004)

Such an unexpected choice of music can put more emphasis on the shot, and in fact can make it more dramatic and more memorable. But use this ironic technique sparingly—it can easily be overdone, too, so be careful.

One firm rule of mine is to not use any kind of electronic or synthetic music, which I hate. I prefer music using real, uncomputerized sounds.

When I’m choosing music for my films, I try to stay away from the big-name acts—there’s no way I can afford a famous band. Therefore, I have a lot of musician friends whose music I use, and they also suggest other talented musicians.

ME, MAUREEN MCELHERON, AND HANK BONES AT A HAIR HIGH MUSICAL SESSION (2003)

In fact, Hank Bones, who’s created a lot of great music for my films (especially the wonderful soundtrack for Hair High) would often have big backyard music parties, and all these fabulous talented musicians would perform. They were like big country hootenannies, and I’ve met a lot of my favorite musicians at these wonderful events.

I then have a large stack of CDs with tracks that I want to use in my film. But how much do I pay?

The total music budget for Idiots and Angels was set at $10,000. Now, I know that sounds very low, and it is, but I was really broke at that time (in fact, I’m still broke as I write this), and I could barely afford that. I wanted to use about 30 songs, so you can see that works out to about $300 per song.

Now, I was able to get by with some freebies. The John Philip Sousa march I wanted to use was performed by the US Marine Band, and it was very old, so it was in public domain (plus, as a military recording, the US taxpayers own it). Another track was by an old cartoonist friend of mine, and he donated the song to the film. But happy accidents like these are very rare.

Most of the musicians I contacted grumbled about the $300 fee, but eventually they made the decision to accept it because they felt it would give their song some exposure, and perhaps they’d make extra money when the film eventually played on TV. Royalties like this are paid by a cable TV station to the songwriters through ASCAP or BMI and don’t cost me a thing!

I’m going to cite five interesting examples of how I got some of my music for Idiots and Angels.

Example #1: I love the band Pink Martini. They’re from my hometown of Portland, and their music was perfect for my film—very evocative and emotional. The good news was that I’d known the band’s leader, Thomas Lauderdale, since he got out of college—he did a very funny cameo appearance in my second live-action film, Guns on the Clackamas, in 1985; also, my talented brother Peter is the band’s sound engineer. So I get to see the band whenever they perform in New York, and we all hang out after.

In fact, there is a nice kinship between Pink Martini and me—they travel a lot (like me), they’re totally independent (like me), and they produce and distribute their CDs to huge success (unlike me, but I’m working on that). So they’ve been very supportive of my films, and they charge me a very fair price for their music.

Example #2: The opening and closing song for Idiots and Angels, which features Whistling Geert, is very important because it’s a unique song that’s very compatible to my film. I met Whistling Geert at the Florida Film Festival; he was there from Holland with a documentary about him being the whistling champion of the world. Well, we got drunk together, and as I listened to his music, I boldly claimed that I wanted to use that one particular song for my next film—and he said, “Yeah, great, no problem!”

However, his producer had different ideas—he wanted $8,000 for the rights to that song! Whoa, that was almost my entire music budget! I think he assumed that since I was making a film in the United States, it must be a big Hollywood film for which those kinds of budgets are normal. After I explained that this was certainly not a Hollywood film, but in fact an indie film with a lower budget, and then begged and pleaded on my knees (it was on a longdistance phone call, but I think he knew I was on my knees), he came down to $5,000—still way too much.

So I called back the next day, and I offered all kinds of incentives to get him to meet my price. I said I’d give him a piece of art from the film, plus I’d create his next CD cover and I’d even create a music video for the band. Well, I guess that was the final deal maker, or else he just felt sorry for me, because we signed the deal for just a bit over my normal rate.

Example #3: Tom Waits. While I was drawing Idiots and Angels, I listened to a lot of his music to get me in the mood of the bar scenes. His songs just evoke a lot of that barfly culture—so many of them are about drinking and its consequences. This kind of approach is really dangerous, because you can get to a point where you fall in love with some music, and you absolutely have to have it, even though you probably can’t afford it—well, that’s what happened to me.

I don’t know Tom Waits personally, I’ve never met him, and I’ve heard that he’s very reclusive. But I do know Jim Jarmusch, and I know they go back to Jarmusch’s film Down By Law, so I sent Jim a rough cut of Idiots and Angels and asked if he could pass it along to Mr. Waits.

Well, after about a month of not hearing anything, I figured the deal was off. Then I got a nice email from Tom’s wife saying that he loved my film, and I could have any song I wanted for it. Yee-hah! There was a Santa Claus! Of course, I still had to pay for the song rights, but it was at a reduced rate (one that just barely fit within my budget). Still, I was ecstatic.

It just shows you what a cool guy Tom Waits is—he likes to support projects that are interesting and show an affinity to his music.

Example #4: One of my favorite scenes in Idiots and Angels is the one with the guy entering the bar, which I talked about earlier. It’s so beautiful that I wanted to get the top pedal steel player in the United States—no, make that the world. So I called up Larry Campbell. Now, Larry and I go way back; he did a couple of steel guitar riffs for the Wiseman segment in my first animated feature, The Tune.

This was back in 1991—Larry was new in town and very accommodating. Well, since then he’s become a steel guitar superstar, working for people like Levon Helm, Bob Dylan, and Emmylou Harris (more about her later). When I called Larry, he said he was way too busy touring, working on an album, and doing some commercials. But I sent him a rough cut of the film, with temporary music by Daniel Lanois, so he could (hopefully) fall in love with it.

I always use temp music because it really helps to get a feel for the mood and tempo of the film—also, it helps when I show people the rough cut, in that it gives them a better idea about the finished product. However, I do recall that one time I used some temp music from Cirque du Soleil on a rough cut of Hair High, and two weeks later I got a call from their lawyers, asking me for $5,000 for the use of that song.

I don’t know how they heard that I used their song as a temporary track, but I guess those lawyers are ever-vigilant. I showed the piece to only a few people! So I told them that it was only in there to get a feel for the emotion, that I’d never include it in the final film without permission, or sell it or show it at a festival or on TV. Also, I agreed to immediately take it out of the film, and the lawyers went away.

Anyway, I kept pestering Larry Campbell, and finally he said that in about three weeks, he’d have an hour of time for me. Wow, one hour! So, when the time came, I picked him up, with his steel guitar, and we grabbed a cab down to the sound session, arranged by my sound designer, Greg Sextro. We got him set up, he recorded the song in two takes, and I gave him money for a cab home. I think he made it back with five minutes to spare. I had to pay him a little extra, because he’s Larry Campbell, but you know what? It was worth it, because that scene became a knockout!

And the last musical story I’ll tell you happened when I was at the Sundance Festival. I think I was screening I Married a Strange Person there. I was at a party one night, and when I turned around, standing behind me was Emmylou Harris—Emmy-friggin’-lou Harris!

EMMYLOU HARRIS, ME, AND MARY KAY PLACE, ACTRESS AND SINGER, AT SUNDANCE (1998)

She’s my country goddess—I’ve listened to more of her music than anyone else’s, even the Beatles. I nervously introduced myself to her, and I told her I was an animator. That didn’t get much of a rise out of her, so I told her it was my greatest wish to use some of her music in one of my movies. Again, that didn’t seem to cause too much enthusiasm on her part—she probably hears that a lot.

I asked for her address, to send her some of my work, and she gave me her agent’s contact information. Wow! I was so excited. I figured if she liked my animation, she might let me use a song. So as soon as I returned to New York, I mailed off a package containing every film and book I ever made. And … I never heard back from her.

I think what happened was that I came off as a complete stalker, and she probably told her agent to trash anything that came in the mail from some crazy person named Bill Plympton. But one day—you never know.

The trick is to keep your music budget as low as possible. You can often get better music, and more rights, from an undiscovered or up-and-coming musical act than from a more established band.

Some bands are so excited to see their music set to animation that they may even pay you and use the scene as a sort of music video. I recommend haunting all the local music clubs and small concert halls and making friends with a lot of musicians. This is how you can find great music at a great price.

Also, you can tell them that when the film plays on TV, they’ll get some fat royalty money, as long as they’re registered with ASCAP or BMI.

I work with a number of composers—Maureen McElheron, Hank Bones, Corey Jackson, and Nicole Renaud—and my working relationship with each of them is pretty much the same. I send them the storyboards or rough art of the pencil test so that they can get an idea of the film; then we discuss musical ideas, instrumentation, tempo, and size of ensemble.

I may have some of their music already on the sample reel or some other piece of music as a temp track. Then, after a few weeks, they’ll play me a rough version of what they had in mind and we’ll discuss how it works with the story and picture. Then they’ll go back and do a finished piece of music.

Hopefully, the finished music will sync up with the film—if not, we have two options: change the speed of the music, or retime the animation. In any case, getting the music to time up with the picture is of paramount importance.

It’s such a great feeling to witness a film in which the music and picture compliment each other.

NICOLE RENAUD, COLOR PENCIL (2010)

Before you can use a piece of music in your film, you have to get the rights, also known as music clearances. Performance rights refers to the actual recorded music on a CD, and clearing this music often means negotiating with the record label or a manager or a producer.

Then there are publishing rights, which refer to the composition of the song itself, and getting these cleared means negotiating with the songwriter. Sometimes the songwriter is also the performer, but not always, and sometimes you have to talk to the writer’s management instead.

Whenever possible, I try to deal directly with the performer or songwriter, because he or she is usually much more willing to make a deal than lawyers or agents are. Sometimes it seems like the lawyers are trying to prevent the use of a song, rather than encourage it.

Also, it’s very important to get all film usage rights initially in all territories for perpetuity. If you only buy festival rights at a cheap price, and then your film becomes a hit, the lawyers smell money and will jack up the price for the theatrical rights because they know you’re desperate to make a deal.

A lot of filmmakers use music in the public domain—this is most often older music with copyrights that have expired. Perhaps the most successful of these filmmakers is Don Hertzfeldt, famous animator of the short “Rejected.” Check out Don’s films if you haven’t already. He’s the only other guy I know who regularly makes a profit on his short films—and that’s maybe because his films are very cheap to make. They’re essentially stick-figure cartoons, for Christ’s sake.

Don draws and shoots all the animation himself and records the voices and sound effects. Hell, he probably makes his own prints in his darkroom lab. But he’s very effective in using classical music that has passed into the public domain. This is a great way to get some of the best music ever recorded—Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms—for almost free. You might just have to pay a small fee for the recording rights, and it will be yours in perpetuity. You can find a lot of classical music available on the Internet, at sites like sounddogs.com.

For examples of music contracts, you can go to http://www.musiccontracts101.com/docs/sample/.

WITH DON HERTZFELDT AND MIKE JUDGE IN NYC

I read once that Steven Spielberg hates to test his films—that he has to be forced to prescreen his films before releasing them. Now, I’m a huge fan of Spielberg, but I swear by testing my films. It’s certainly not an enjoyable exercise, but it’s extremely useful. If I’ve spent three years and $200,000 on a film, I want to make damn sure that it will be popular with the audience. And the only way to do that is to get feedback—lots of feedback.

There’s nothing worse than going to a screening of your finished film and watching it completely flop in front of an audience—by that time, it’s too expensive to make any beneficial changes. So you’d better be certain that what you’re sending out to the festivals and theaters is as good as it can be.

For me, it starts with the storyboard. I have a few very close friends in the business who understand storyboards. I show them the completed storyboard, in hopes of getting some suggestions on how to make it better. I figure that if changes need to be made, that’s definitely the cheapest time to make them.

The next stage for testing is after the pencil test is done. I’ll often put temp music, voices, and basic effects on the film and show it around. My pencil tests are pretty tight; I include a lot of shading and detail, so it won’t take a lot of imagination to see what might be wrong with the film. Sometimes I’ll even get a large audience to view this version.

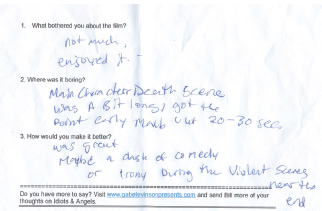

MY SAMPLE QUESTIONNAIRE FOR THE CHICAGO SCREENING OF IDIOTS AND ANGELS (2007)

In 2007, I was able to show a pencil-test version of Idiots and Angels to a large crowd at the great Music Box Theatre in Chicago. We had an audience of about 300 people, and they filled out questionnaires about the plot, the characters, and what worked and what didn’t, which was very helpful. Of course, there were some whackos who missed the mark completely or didn’t get what I was trying to say—those surveys I tossed out. But when there was a consensus about a problem, I paid very close attention and tried to resolve it.

Finally, when the film is finished, colored, sound-mixed, and ready to go to the lab, I’ll show a DVD to another audience, and of course I’ll watch it numerous times myself. There’s still time at that stage to make it better, and I definitely want to send out the best product I can.

It’s also instructive to show the film to a small group of strangers and then talk to them after the screening and ask them more direct questions, probing their deeper feelings about the film. At this type of showing I get really good, impartial criticism and perhaps learn the reasons why they don’t like certain parts of my movie.

To me, testing is essential to the success of a film, no matter what Mr. Spielberg says.