In This Chapter

Configuring .NET Framework applications and security.

Implementing UDDI and other Web Services support.

Understanding why developers are so excited about Windows Server 2003.

Windows Server 2003 comes out of the box with Microsoft's latest software development technologies. If you're reading this book, however, you probably consider yourself more of an administrator than a developer, so do you even need to worry about these technologies? The answer is an emphatic “Yes!” because Windows Server 2003, more than any previous version of Windows, is designed to host powerful, enterprise-class applications. You need to be familiar with these development technologies so that you can understand their impact on your servers, and so that you can install servers that provide the best possible support for your organization.

Windows Server 2003's most visible new development feature is the .NET Framework, which is an entirely new set of software development technologies. Software developers will use tools like Visual Basic .NET, C# (pronounced “C Sharp”), and Visual C++ .NET to create applications that use the .NET Framework.

One of the reasons software developers are so excited about the .NET Framework is that it makes creating Web services applications easier. Web services applications are designed to work in conjunction with Internet technologies, providing services over HTTP and other common Internet protocols. For example, a home insurance firm might offer a Web service that accepts home values, locations, and other information and provides insurance quotes. Real estate agents could incorporate this Web service into their own applications or Web sites, taking advantage of the capabilities offered by the Web service without having to write the complicated code themselves.

Of course, after companies start providing these Web services, they need a way to organize those services so that others—whether inside or outside the company—can locate and use the services. Windows Server 2003 provides a means for that organization of services in its included Universal Description, Discover, and Integration (UDDI) services. Other development enhancements that should catch your attention include Enterprise Services (the name for the latest version of Microsoft's venerable COM+ technology), Web farm technologies, and much more. We'll cover all these items in this chapter, focusing on them from a server administration point of view so you can better implement and use these new capabilities in your environment.

The .NET Framework represents an entirely new way of thinking about software development. You're probably familiar—even if you don't realize it—with the “old way” of creating software applications, which is illustrated in Figure 9.1. Developers would use a tool such as Visual Basic 6.0 to create software applications. When they were finished, the tool compiled their program code into native code, a form of program code that can execute directly on the operating system. Physically, Visual Basic code exists in simple text files, which the operating system can't execute. Compiled programs, however, exist in familiar EXE files, which can execute directly on the operating system. This software development technique has been around in one form or another since the beginning of computer programming and is capable of producing applications with very good performance.

Figure 9.1. Traditional software development produces executables for a specific operating system and hardware platform.

There are a number of problems with this traditional programming model:

Executables produced in this fashion only run on a specific operating system and hardware platform—. As enterprises continue to implement a wider variety of hardware and operating systems—including portable devices like Pocket PCs—developers have to work harder to make their programs run throughout the enterprise. Each new operating system/hardware combination requires specialized development tools and often requires developers to start programming from scratch for each platform.

Very few popular programming tools take full advantage of the object-oriented nature of Windows—. Object-oriented programming saves time and money by allowing developers to create small sections of code to perform specific tasks and then easily reuse that code in several different projects. A powerful object-oriented language also allows developers to reuse functionality inherent to the operating system, such as drawing windows and buttons, accessing files and networks, and so forth.

Different programming languages have different strengths and weaknesses, and developers have to choose one and pretty much stick with it—. Each language typically operates in a completely different fashion, making it very difficult for developers to switch back and forth between languages when working on different projects. As a result, developers tend to pick one language and stick with it, even if it isn't ideal for the task at hand.

The purpose of the .NET Framework is to address all these issues. For starters, Microsoft has provided new, .NET-compatible versions of its popular Visual Basic and C++ programming languages and introduced a new language named C#, which is similar in many respects to the popular Java programming language from Sun Microsystems. Although each of these languages has a different syntax, or grammar, they all offer the same basic capabilities. For example, developers who wanted to interface closely with the operating system used to choose Visual C++ as their language, often because languages such as Visual Basic didn't provide close operating system integration. Under .NET, that's no longer true: Each of the .NET languages provides the same capabilities, allowing developers to work in whatever language they're most comfortable with. Even better, all the languages can be used from within the same development tools (such as Visual Studio .NET), so that developers can switch languages without having to learn an entirely new set of tools.

The .NET Framework's changes go beyond developer convenience, though. When compiling a Visual Basic 6 application, developers produce an executable file. In Visual Basic .NET (or any other .NET language), however, compiling is simply an automated process in which the .NET Framework translates the developer's program code into a universal programming language called the Microsoft Intermediate Language (MSIL, or just IL). What's more, IL doesn't even execute directly on the operating system. Instead, IL is executed inside a virtual machine called the common language runtime (CLR). The CLR actually reads the IL and compiles it into a form of native code. This final compilation occurs when the program is executed and is referred to as just in time (JIT) compilation. The CLR improves performance by saving the compiled program and reusing it until the original code is changed and recompiled into IL by the developer; at that time, the CLR recompiles the new IL and executes it. Figure 9.2 illustrates the new development environment the .NET Framework uses.

So, what's the purpose of this extra complexity? Developers no longer write code for a specific operating system. Instead, they write for the CLR itself, which allows their code to execute more or less unchanged on any platform for which a CLR is available. Microsoft already provides a CLR for Windows and a Compact CLR for Pocket PCs and other Windows CE devices. The future might bring Linux- or Unix-compatible CLRs, allowing .NET applications to run (hopefully) unchanged on a completely different operating system. This capability solves another traditional development problem by allowing developers to write one program that runs on all of an enterprise's various computing devices.

This business with the CLR and cross-platform compatibility should sound familiar because it's what Java advocates have been preaching since their product was introduced. Java uses a similar development model in which developers write Java-specific code, which is executed by a Java Virtual Machine (JVM). So long as a JVM is available for a specific platform, that platform can run virtually all Java applications. If you've used Java applications, however, you might have noticed that they don't perform quite as quickly as native-code applications written in Visual Basic 6.0, Visual C++ 6.0, or other traditional programming languages. That performance decrease is inherent in any virtual machine technology: Rather than executing an application directly on the operating system, both Java and .NET execute the application within a virtual machine (the CLR in the case of .NET), and the virtual machine itself is executed by the operating system. In other words, the virtual machine represents an extra layer of code that has to be executed, which reduces performance.

Although .NET applications tend to perform pretty well, they can't compete with native-code applications, especially those written in Visual C++ (the language Windows itself is written in). For that reason, you won't see Microsoft using the .NET Framework to develop the next versions of its .NET Enterprise Servers, such as Exchange Server and SQL Server. Those will continue to be written in native code for a specific platform. Perhaps some future version of the CLR, combined with the ever more powerful hardware being created, will enable powerful server applications to be written in .NET, but that day is probably a long way off.

So, what does an administrator need to know about the .NET Framework? Prior to Windows Server 2003, the .NET Framework itself had to be installed before .NET applications could be installed and executed; Windows Server 2003, however, comes with the .NET Framework built right in, so your developers can immediately start installing and executing .NET applications on your servers. So, although deployment is a piece of cake, an additional administrative effort is involved because the .NET Framework adds whole new levels of security and management to your servers. In fact, Windows Server supports an entirely new console called the .NET Framework Configuration Console, shown in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3. The .NET Framework Configuration console enables you to modify the behavior and other properties of the .NET Framework.

This new console allows you to manage five aspects of the .NET Framework:

Assembly Cache—. Assemblies are basically modules of code that are shared by several applications. For example, a developer might create a logon routine and use it in all his corporation's custom applications. The Assembly Cache acts as a storage area for these assemblies, making them available to the applications running on the server.

Configured Assemblies—. Assemblies from the assembly cache can be organized into sets and associated with different rules. These rules determine which version of assemblies are loaded and which location is used to load the assemblies.

Code Access Security Policy—. The .NET CLR includes a complete set of code access security policies that control applications' access to protected resources. This extra layer of security ensures that only authorized applications can get to sensitive server and network resources and prevents unauthorized applications from wreaking havoc on your network.

Remoting Services—. These services enable applications to communicate with applications on other computers, and the console allows you to adjust the communications properties.

Individual Applications—. You can configure each .NET application with its own set of configured assemblies and remoting services, customizing the behavior of each application to meet your precise needs.

You might find yourself wondering whether many of these tasks are more properly suited to a developer rather than an administrator. Only time will tell if that's the case, but we firmly believe that administrators are responsible for the overall operation, efficiency, and security of the enterprise network, and that places these five configuration tasks firmly in the administrator's realm. Developers often become too focused on a particular task and don't take the health and well-being of the entire network into consideration, leaving it to the administrator to make sure everything is configured safely and efficiently. With that in mind, we'll spend the next five sections briefly covering each of the major .NET Framework configuration tasks.

Adding an assembly is pretty easy—just right-click Assembly Cache and select Add from the pop-up menu. As shown in Figure 9.4, the console displays a complete list of available assemblies. You'll need to rely on your developers to tell you which assemblies are required by their applications and to provide those assemblies for installation on your server.

One great feature about the assemblies list is the inclusion of each assembly's version number. This feature enables you to quickly determine which version of an assembly is running, thereby ensuring that the correct assemblies required by .NET applications are available on the server.

Adding a configured assembly is also pretty straightforward. Right-click Configured Assemblies in the console and select Add from the pop-up menu. Select an assembly from the assembly cache, and then specify the assembly's configuration properties, as shown in Figure 9.5.

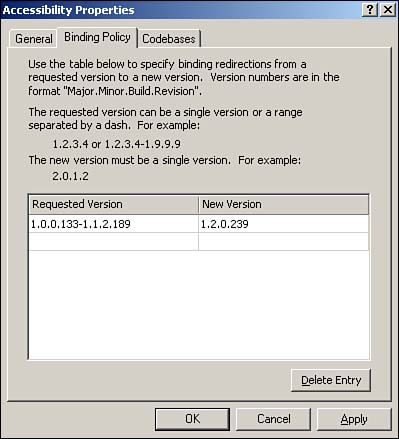

A binding policy tells the server how to handle requests for different versions of the assembly. Multiple versions of an assembly can reside in the assembly cache at the same time; which version an application gets when it requests the assembly depends on the binding policy you set. The example in Figure 9.5 is for an assembly named Accessibility. Any application requesting version 1.0.0.133–1.1.2.189 of the assembly is given version 1.2.0.239, which must reside in the assembly cache. Binding policy enables you to actively manage backward compatibility because you can specify which version of the assembly will be used with a given request for a particular version.

Codebases are network-accessible versions of assemblies, which enable applications to load assemblies that aren't available in the server's assembly cache. You must specify the version of the assembly that an application might request and then provide a URL—either an http:// URL or a file:// URL—where a compatible assembly is located.

Windows Server groups security policies into three levels: per-enterprise, per-machine, and per-user. You can establish different security policies at each level. The security policy is basically a combination of code groups and permission sets. A code group simply organizes code into manageable groups. Permission sets define sets of permissions for code, such as the capability to access the file system, network, and other resources. It's important to understand that the effective permissions on any particular assembly are the combination of the enterprise, machine, and user policy levels. Each assembly might belong to different code groups at each level and will receive the most restrictive combination of permissions from all three levels. You can think of this behavior as similar to user groups and file permissions: Users can belong to multiple groups and receive the combination of permissions available to each group to which they belong.

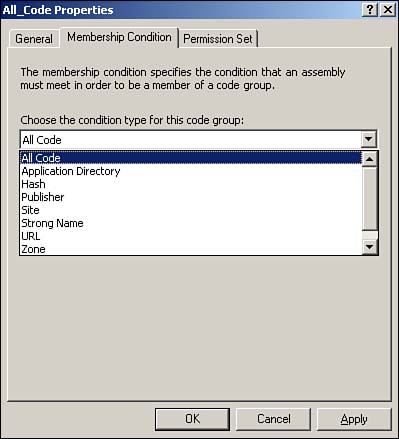

Windows Server includes a default All_Code code group at each policy level. As shown in Figure 9.6, the membership condition of this group is simply All Code. You can define other code groups with different membership conditions, such as “all code in a certain folder” or “all code from a particular publisher.” You then assign a permission set (Windows Server includes several predefined sets) to determine what the code within the group is allowed to do. There's even a default Nothing permission set, which prevents code from executing at all. This can be useful for preventing the execution of code that is known to be harmful.

For more information on the .NET Framework security permissions, see Chapter 4, “Security,” p. 45.

Figure 9.6. Code groups and permission sets enable you to define precisely what different applications can do on your servers.

You can think of code groups as similar to domain user groups. Rather than explicitly placing applications within a code group, as you do with users, you specify rules. It's as if you could specify a rule that places all users whose names begin with D in a particular user group. And you can think of permission sets as preconfigured sets of file permissions. By assigning a permission set to a code group, you grant specific privileges to the code contained within the group.

Remoting Services allows applications to communicate with applications located on other computers. These communications take place via communications channels. By default, Windows Server provides two channels: TCP and HTTP. Neither of these channels provides any significant properties that you need to configure. Other communications channels can be installed on a server to allow communication over different networks or with different levels of security; these channels might provide properties that you need to configure through the Remoting Services portion of the .NET Framework Configuration Console.

To add a new application to the console, right-click the Applications item and select Add from the pop-up menu. The console displays a list of recently executed applications, from which you can select an application to add. You can also select any other application if the one you want isn't displayed on the list. For each application you add, you can do the following:

Modify the application's properties—. This includes publisher policy, a private folder path used to locate additional assemblies, and so forth. Your developers will need to help you configure these properties if they should change from the defaults.

View the application's dependencies—. This is a list of all assemblies used within the application. This feature can be useful when you're installing an application written by a third party or a poorly documented application because it helps you track down the assemblies the application needs to run properly.

Manage Remoting Services for this particular application—. Applications that use Remoting Services need additional configuration information here, which your developers should be able to provide to you.

Fix the application—. This great tool examines the application and looks for problems with its dependencies. The tool can even modify the application's configuration file to fix certain problems. This tool is useful when installing a poorly documented application to check for dependency issues that can otherwise be difficult to track down.

You can also configure a private set of configured assemblies for the application, enabling you to create a custom configuration that affects only this particular application, rather than a generic configuration that affects all applications on the server.

Web Services, as we've already described, are essentially reusable software applications that are accessible through Internet technologies, such as the HTTP protocol. For example, suppose that one of the developers at your company's headquarters creates a Web service that provides access to your company's customer database. All your company's other developers can immediately take advantage of this service by incorporating it into other applications. No other developer will ever again need to write code to access the customer database because he can simply use the existing Web service. One important enabling technology behind Web services is XML, and more specifically the SOAP protocol. SOAP stands for Simple Object Access Protocol, and it's simply a protocol that enables one application to use another application's services across the Web (or any other TCP/IP-based network). Another important standard is the Web Services Description Language (WSDL), which is a standard for describing how Web services work and what specific capabilities a service offers. Developer tools such as Visual Studio enable developers to create Web services and export their capabilities in WSDL; other developers can import the WSDL into their own applications to use Web services with little additional coding.

Of course, keeping track of all these WSDL files can be cumbersome, so Windows Server also includes UDDI. When you install UDDI, it attaches itself to IIS and can install a copy of the Microsoft Database Engine (MSDE), a scaled-down version of Microsoft SQL Server 2000. UDDI essentially stores WSDL information in SQL Server and provides an HTTP-accessible means of adding and retrieving WSDL information. Visual Studio .NET includes built-in UDDI support, allowing it to import and export WSDL to and from UDDI directly. That's plenty interesting if you're a developer, but even administrators need to be aware of UDDI and the impact it can have on software developers. Specifically, administrators need to install UDDI, which is an optional component of Windows Server. Administrators also need to decide whether UDDI will use an existing SQL Server or if it should install its own copy of the MSDE for storage purposes. Finally, administrators are responsible for troubleshooting and maintaining UDDI. One key troubleshooting tool is UDDI logging, which administrators configure from within the UDDI Console. As shown in Figure 9.7, you can select a variety of logging levels that provide progressively higher levels of detail.

Figure 9.7. The UDDI Console is installed along with UDDI itself, which is an optional component of Windows Server.

Web Services offers a significant benefit to administrators: easy deployment. When developers create Web services with the .NET Framework, and most especially with ASP.NET, they allow administrators to easily deploy and manage applications. For example, suppose a developer writes a new ASP.NET application and deploys it to a test server. When testing is finished, you need to deploy it to any number of Web servers. With older ASP applications, that could be pretty complex and involve Registry keys, DLL registration, and much more. Under ASP.NET, you basically just copy the files from one server to another. The .NET Framework itself takes care of the rest, recompiling assemblies as necessary on-the-fly. When developers update the application, you just copy the new files. There's no need to unregister DLLs, uninstall applications, and reinstall everything; a simple file copy is all that's needed for most ASP.NET applications.

Windows Server also includes Enterprise Services, the latest version of Microsoft's COM and COM+ technologies. Enterprise Servers enables developers to more easily create distributed, enterprise-class applications by making many complex tasks—such as transaction handling, application security, and so forth—available directly from the operating system. Enterprise Services provides several enhancements that are, frankly, only of interest to serious developers. Although it's nice to know that these services exist, they don't really have much impact on an administrator, other than as an explanation for why your developers are so interested in getting Windows Server up and running. If you're interested in reading more about the Enterprise Services features, visit msdn.Microsoft.com/library. In the left menu, drill down to Component Development, Enterprise Services, Technical Articles, Windows Server 2003 and Enterprise Services.

One tremendously important development enhancement is part of the .NET Framework: ASP.NET. ASP.NET is the newest version of Microsoft's Active Server Pages (ASP) technology, which helped make IIS one of the most popular commercial Web servers available. ASP.NET was designed from scratch to address many of the problems that became apparent as ASP was adopted in larger environments.

Note

For more information on how ASP and ASP.NET work, and why you should care, go to the book's product page at www.informit.com/store/product.aspx?isbn=0789728494. Click the Extras tab and locate article ID# A010901.

Windows Server even offers improvements in some of the development technologies that were already present in older versions of Windows:

The .NET Framework is, of course, included with Windows Server, so you don't have to worry about deploying it separately like you did with Windows 2000.

The .NET Framework's runtime security works along with software restriction group policies, giving you powerful tools to manage the software that runs on your servers.

Microsoft's Message Queue Service (MSMQ) supports SOAP as a native protocol, making MSMQ more accessible to developers of Web services.

Under Windows Server 2003, legacy COM+ applications can be converted to a Web service by selecting a check box. This powerful capability relies on Windows Server 2003's native Web services support and enables companies to more easily move their existing applications into a Web services environment.

ASP.NET, which works with IIS 5.0 in Windows 2000, is integrated more tightly with IIS 6.0 in Windows Server 2003, providing full process model integration for more reliable applications.

Windows Server 2003's inclusion of Network Load Balancing (NLB) in all editions (as opposed to only including NLB in the Advanced Server and Datacenter Server editions of Windows 2000) provides better support for scalable applications and Web farms.

Your developers will probably be eager for Windows Server 2003 to be rolled into production, so they can start taking advantage of these new features.