CHAPTER 21

Product Manufacture and Distribution

Given the huge number of changes that have occurred within the business of music marketing and media distribution, it stands to reason that an equally large number of changes have occurred when it comes to planning and considering how you are going to get your new-born project out to the masses. In short, many of the rules have changed, and it’s the wise person who takes the time to put their best foot (and plan) forward to make it all shine. So, having said this—what are our best options for reaching people in this day and age? Well there’s:

■ CD: Some would call this a dying breed, but when you walk into a music store, you’ll see them everywhere. Fact is, a lot of people still like to have their music media “in hand.”

■ DVD and Blu-ray: Still the preferred medium for visual media (but just barely). Of course, DVDs are good for movies and for music video/live concerts (usually with a 5.1/7.1 soundtrack). Blu-ray discs, also tout high-definition video, but are also a medium for getting high-resolution 5.1/7.1/9.1 music out to the masses in a physical form.

■ Vinyl: We’re all pretty much aware of vinyl’s comeback as a viable music medium. It’s the perfect in-hand “see what I just got?” product—having both a huge retro allure and saying to those around you that you care enough about your music to dare to be different.

■ Online (download) distribution: The 700-pound gorilla in the room. Online music sites exist in the hundreds (probably thousands) although the biggies (iTunes, CDBaby, Google Play, Amazon Digital Music, etc.) still are at the top of the digital download heap, allowing us to collect and consume albums or single tracks when and where we want them.

■ Hi-res download distribution: Similar to online music download services, high-resolution sites allow us to download our favorite classical, new release or newly-remastered, high-res version of our favorite older classics. Most often being offered as larger, hi-res 24/96 sound files, these special releases offer up the highest-quality versions of a master recording. Again, this is presented to customers that value the quality (or perceived “specialness”) of their personal hi-res music collection.

■ Music streaming: The other 700-pound gorilla that a lot of online distribution companies are trying to come to grips with. The idea being that paying a monthly subscription to a music service will give us instant access to their entire music library in an on-demand fashion—usually without the option of owning a physical or download copy of our (well, actually—their) music. It worked for video streaming (i.e., Netflix) so, why not for music?

■ Free music streaming: One of the biggest music services on the web is (at the present time) actually free. YouTube has eclipsed many of the streaming services as an outlet for getting music, DJ playlists and music videos out to the public.

With all of these distribution methods, one of greatest misconceptions surrounding the production of music, visual and other media is the idea that once you finish your project and have the master files in hand, your work is done; that the production process is now over. Of course, this is far from being the truth. There are many decisions that need to be made long before the process has been finished (and most often, long before the project has even begun). Questions like:

■ Can we define who the market is and take steps to make “the product” known to this market?

■ Will it be self-distributed or will it be released by a music label who knows the ins-and-outs of the business and how to get “the product” out to the masses?

■ Will it be available in physical form and/or online?

■ Will there be a marketing strategy and budget?

All of these will definitely need to be addressed. One of the biggest mistakes that can be made during the creation of a project is to think that your adoring public will be clamoring for your product, website and merchandise without any marketing strategy or general outreach strategy.

Early in this book, I told you about the first rule of recording—that “there are no rules, only guidelines.” This actually isn’t true. There is one rule:

If you don’t pre-plan, and follow through with your production and marketing strategies, you can be fairly sure that your project will sit on a shelf. Or, worse, you’ll have 1,000 CDs sitting in your basement that’ll never be heard or downloads that will be lost in the deep digital ocean—a huge shame given all the hard work that went into making it.

Now that we’ve gotten the really important idea of pre-planning your strategies across let’s have a look at the various media. How they are made and how they can best be utilized to get the word out to the public.

PRODUCT MANUFACTURE

Although downloadable and streaming media are well on their way toward dominating the music and media industries, the ability to buy, own and gift a physical media object still warms the hearts of many a media product purchaser. Often, containing uncompressed, high-quality music, these physical discs and records are held in regard as something that can be held onto, looked at and packaged up with a big, bright gift bow. Their major market-share days may be numbered but don’t count them out any time soon.

The CD

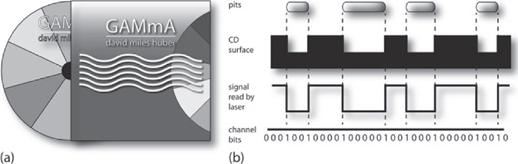

Beyond the process of distributing audio over the Internet (using an online service or from your own site), as of this writing, the compact disc (CD) is still a strong and viable medium for distributing music in a physical form. These 120-mm silvery discs (Figure 21.1a) contain digitally encoded information (in the form of microscopic pits) that’s capable of yielding playing times of up to 74 or 80 minutes at a standard sampling rate of 44.1 kHz with a 16-bit-depth.

The pit of a CD is approximately half a micrometer wide, and a standard manufactured disc can hold about 2 billion pits. These pits are encoded onto the disc’s surface in a spiraling fashion, similar to that of a record, except that 60 CD spirals can fit into the single groove of a long-playing record. These spirals also differ from a record in that they travel outward from the center of the disc, are impressed into the plastic substrate, and are then covered with a thin coating of aluminum (or occasionally gold) so that the laser light can be reflected back to a receiver. When the disc is placed in a CD player, a low-level infrared laser is alternately reflected or not reflected back to a photosensitive pickup. In this way, the reflected data is modulated so that each pit edge represents a binary 1, and the absence of a pit edge represents a binary 0 (Figure 21.1b). Upon playback, the data is then demodulated and converted back into an analog form.

FIGURE 21.1

The compact disc. (a) Physical disc and package. (Courtesy of www.davidmileshuber.com) (b) Transitions between a pit edge (binary 1) and the absence of a pit edge (binary 0).

Songs or other types of audio material can be grouped on a CD into tracks known as “indexes.” This is done via a subcode channel lookup table, which makes it possible for the player to identify and quickly locate tracks with frame accuracy. Subcodes are event pointers that tell the player how many selections are on the disc and where their beginning address points are located. At present, eight sub-code channels are available on the CD format, although only two (the P and Q subcodes) are used.

Functionally, the CD encoding system splits the 16 bits of information into two 8-bit words with error correction (that’s applied in order to correct for lost or erroneous signals). In fact, without error correction, the CD playback process would be so fragile and prone to dropouts that it’s doubtful it would’ve ever become a viable medium. This information is then translated into a data frame, using a process known as eight-to-fourteen modulation or EFM. Each data frame contains a frame-synchronization pattern (27 bits) that tells the laser pickup beam where it is on the disc. This is then followed by a 17-bit subcode word, 12 words of audio data (17 bits each), 8 parity words (17 bits each), 12 more words of audio, and a final 8 words of parity (error correction) data.

THE CD MANUFACTURE PROCESS

In order to translate the raw PCM of a music or audio project into a format that can be understood by a CD player, a compact disc burning system must be used. These come in two flavors:

■ Specialized hardware/software that’s used by professional mastering and duplication facilities to mass replicate optical media.

■ Disc burning hardware/software systems that allow a personal computer to easily and cost effectively burn individual or small-run CDs.

Both system types allow audio to be entered into the software, after which the tracks can be assembled into the proper order and the appropriate gap times entered between tracks (in the form of index timings). Depending on the system, sound files might also be processed using cross-fades, volume, EQ and other parameters. Once assembled, the project can be “finalized” into a media form that can be directly accepted by a CD manufacturing facility. By far, the most common media that’s received by CD pressing plants for making the final master disc are user-burned CD-Recordable (CD-R) discs, although some professional services will still accept a special Exabyte-type data tape system.

Note that not all CD-R media are manufactured using high-quality standards. In fact, some are so low in quality, that the project’s data integrity could be jeopardized. As a general rule:

■ It’s always good to use high-quality “master-grade” CD-Rs to burn the final duplication master (you can sometimes see the difference in pit and optical dye quality with the naked eye).

■ It’s always best to send two identical copies to the manufacturer (just in case one fails).

■ Speaking of failing, you should check that the manufacturer has run a data integrity check on the final master to ensure that there are few to no errors, before beginning the duplication process.

Once the manufacturing plant has received the recorded media, the next stage in the large-scale replication process is to cut the original CD master disc. The heart of such a CD cutting system is an optical transport assembly that contains all the optics necessary to write the digital data onto a reusable glass master disc that has been prepared with a photosensitive material.

After the glass master has been exposed using a special recording laser, it’s placed in a developing machine that etches away the exposed areas to create a finished master. An alternative process, known as nonphotoresist, etches directly into the photosensitive substrate of the glass master without the need for a development process.

After the glass or CD master disc has been cut, the compact disc manufacturing process can begin (Figure 21.2). Under extreme clean-room conditions, the glass disc is electroplated with a thin layer of electro-conductive metal. From this, the negative metal master is used to create a “metal mother,” which is used to replicate a number of metal “stampers” (metal plates which contain a negative image of the CD’s data surface). The resulting stampers make it possible for machines to replicate clear plastic discs that contain the positive encoded pits, which are then coated with a thin layer of foil (for increased reflectivity) and encased in clear resin for stability and protection. Once this is done, all that remains is the screen-printing process and final packaging. The rest is in the hands of the record company, the distributors, marketing and you.

As with any part of the production process, it’s always wise to do a full background check on a production facility and even compare prices and services from at least three manufacturing houses. Give the company a call, request a promo pack (which includes product and art samples, service options and a price sheet), ask questions and try to get a “feel” for their customer service abilities, their willingness to help with layout questions, etc. You’d be surprised just how much you can learn in a short time.

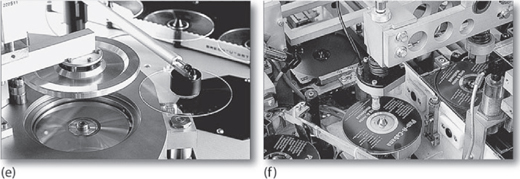

FIGURE 21.2

Various phases of the CD manufacturing process. (a) The lab, where the CD mastering process begins. (b) Once the graphics are approved, the project’s packaging can move onto the printing phase. (c) While the packaging is being printed, the approved master can be burned onto a glass master disc. (d) Next, the master stamper (or stampers) is placed onto the production line for CD pressing.

Note: This figure continues on the next page.

FIGURE 21.2

(e) The freshly stamped discs are cooled and checked for data integrity. (f) Labels are then silk-screen printed onto the CDs, whereafter the printed CDs are checked before being inserted into their finished packaging. (Courtesy of Disc Makers, Inc., www.discmakers.com)

Whenever possible, it’s always wise and extremely important that you be given art proofs and test pressings before the final products are mass duplicated.

Once you’ve settled on a manufacturer, it’s always a good idea to research what their product and graphic arts needs and specs are before delving into this production phase. When in doubt about anything, give them a call and ask; they are there to help you get the best possible product and to avoid costly or time-consum ing mistakes. The absolute last thing that you or the artist wants is to have several thousand discs arrive on your doorstep that are—WRONG! Receiving a test pressing and graphic “proof” is almost always well worth the time and money. It’s never wise to assume that a manufacturing or duplication process is perfect and doesn’t make mistakes. Remember, Murphy’s law can pop up anywhere and at any time!

CD BURNING

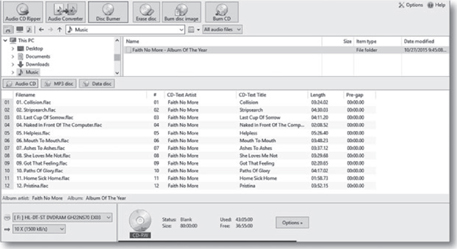

Software for burning CDs/DVDs/Blu-ray media is available in various forms for both the Mac and PC. These include the simple burning applications that are included with the popular operating systems, popular third-party burning applications and more complex authoring programs that are capable of editing, mastering and assembling individual cuts into a final burned master.

There are numerous ways in which a CD project can be prepared and burned. For starters, it’s a fairly simple matter to prepare and master individual songs within a project and then load them into a program for burning (Figure 21.3). Such a program can be used to burn the audio files in a straightforward manner from beginning to end. Keep in mind that the Red Book CD standard specifies a beginning header silence (pause length) that’s 2 seconds long, however, after this initial lead-in, any pause length can be user specified. The default setting for silence between cuts is 2 seconds, however, these lengths will often vary, as one song might want to flow directly into another, while the next might want a longer pause to help set the proper artistic mood.

FIGURE 21.3

EZ CD Audio Converter All-in-one multi format Audio Converter, CD Ripper, Metadata Editor, and Disc Burner. (Courtesy of Poikosoft, www.poikosoft.com)

Most CD burning programs will also allow you to enter “CD Text” information (such as title, artist name/copyright and track name field code info) that will then be written directly into the CD’s subcode data field. This can be a helpful tool, as important artist, copyright and track identifiers can be directly embedded within the CD itself and will be automatically displayed on most CD hard- and software players. Additionally, database services such as Gracenote can be used to display track and project information to players that are connected to the web. These databases (which should not be confused with CD Text) allow CD titles, artist info, song titles, project graphics and other info to appear on most media-based music players—an important feature for any artist and label.

As always, careful attention to the details should always be taken when creating a master optical disc, making sure that:

■ High-quality media is used

■ The media is burned using a stable, high-quality drive

■ The media is carefully labeled using a recommended marking pen

■ Two copies are delivered to the manufacturer, just in case there are data problems on one of the discs

With the ever-growing demands of marketing, gigging and general business practices, many independent musicians are also taking on the task of burning, printing, packaging and distributing their own physical products from the home or business workplace. This homespun strategy allows for individual or small runs to be made in an “on-demand” basis, without tying up financial resources and storage space with unsold CD inventories.

DVD and Blu-ray Burning

Of course, on a basic level, DVD and Blu-ray burning technologies have matured enough to be available and affordable for the Mac or PC. From a technical standpoint, these optical discs differ from the standard CD format in several ways. The most basic of these are:

■ An increased data density due to a reduction in pit size (Figure 21.4)

■ Double-layer capabilities (due to the laser’s ability to focus on two layers of a single side)

■ Double-side capabilities (which again doubles the available data size)

FIGURE 21.4

Detailed relief showing standard CD, DVD and Blu-ray pit densities.

In addition to the obvious benefits of increased data density, a DVD (max of 17 Gb) or Blu-ray (max of 50 Gb—dual layer) will also have higher data transfer rates, making them the ideal media for:

■ The simultaneous decoding of digital video and surround-sound audio

■ Multichannel surround sound

■ Data- and access-intensive video games

■ High-density data storage

As DVD and Blu-ray writable drives have become commonplace, affordable data backup and mastering software has come onto the market that brought the art of video and Hi-Def production to the masses. Even high-level optical media mastering is now possible in a desktop environment. More information on the finer points of codec data compression and media technologies relating these technologies can be found in Chapter 11.

Optical Disc Handling and Care

Here are a few basic handling tips for optical media (including the recordable versions) from the National Institute of Standards and Technology:

Do:

■ Handle the disc by the outer edge or center hole (your fingerprints may be acidic enough to damage the disc over time).

■ Use a felt-tip permanent marker to mark the label side of the disc. The marker should be water or alcohol based. In general, these will be labeled as being a non-toxic CD/DVD pen. Stronger solvents may eat through the thin protective layer to the data.

■ Keep discs clean. Wipe with a cotton fabric in a straight line from the center of the disc toward the outer edge. If you wipe in a circle, any scratches may follow the disc tracks, rendering them unreadable. Use a disc-cleaning or light detergent to remove stubborn dirt.

■ Return discs to their cases immediately after use.

■ Store discs upright (book-style) in their cases.

■ Open a recordable disc package only when you are ready to record.

■ Check the disc surface for scratches, etc. before recording.

Don’t:

■ Touch the surface of a disc.

■ Bend the disc (as this may cause the layers to separate).

■ Use adhesive labels (as they may unbalance or warp the disc).

■ Expose discs to extreme heat or high humidity; for example, don’t leave them in direct sunlight or in on a car’s dash.

■ Expose recordable discs to prolonged sunlight or other sources of ultraviolet light.

■ Expose discs to extreme rapid temperature or humidity changes.

Especially Don’t:

■ Scratch the label side of the disc (it’s often more sensitive than the transparent side).

■ Use a pen, pencil or fine-tipped marker to write on the disc’s label surface.

■ Try to peel off or reposition a label (it could destroy the reflective layer or unbalance the disc).

Vinyl

Obviously, reports of vinyl’s death were very premature. In fact, for consumers ranging from Dance DJ trip-hopsters to die-hard classical buffs, the record is making a popular comeback in record stores around the world. However, the truth remains that only a few record pressing plants are still in existence (they’re currently working their overtime butts off) and there are far fewer discs mastering labs that are capable of cutting “master lacquers.” As a result, it may take a bit longer to find a facility that fits your needs, budget and quality standards, but it’s definitely not a futile venture.

DISC CUTTING

The first stage of production in the disc manufacturing process is disc cutting. As the master is played from a digital source or analog tape machine, its signal output is fed through a mastering console to a disc-cutting lathe. Here, the electrical signals are converted into the mechanical motions of a stylus and are cut into the surface of a lacquer-coated recording disc.

Unlike the compact disc, a record rotates at a constant angular velocity, such as 33 1/3 or 45 rpm (revolutions per minute), and has a continuous spiral that gradually moves from the disc’s outer edge to its center. The recorded time relationship can be reconstructed by playing the disc on a turntable that has the same constant angular velocity as the original disc cutter.

FIGURE 21.5

The 45/45 cutting system. (a) Stereo waveform signals can be encoded into the grooves of a vinyl record in a 45º/45º vector. (b) In-phase groove motion. (c) Out-of-phase groove motion.

The system that’s used for recording a stereo disc is the 45/45 system. The recording stylus cuts a groove into the disc surface at a 90º angle, so that each wall of the groove forms a 45º angle with respect to the vertical axis. Left-channel signals are cut into the inner wall of the groove and right-channel signals are cut into the outer wall, as shown in Figure 21.5a. The stylus motion is phased so that L/R channels that are in-phase (a mono signal or a signal that’s centered between the two channels) will produce a lateral groove motion (Figure 21.5b), while out-of-phase signals (containing channel difference information) will produce a vertical motion that changes the groove’s depth (Figure 21.5c). Because mono information relies only on lateral groove modulation, an older disc that has been recorded in mono can be accurately reproduced with a stereo playback cartridge.

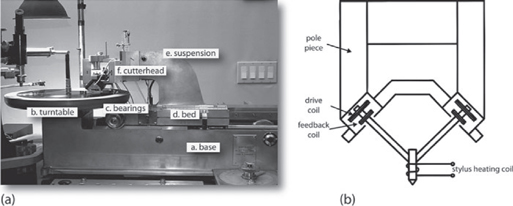

Disc-Cutting Lathe

The main components of a vinyl disc-cutting lathe are the turntable, lathe bed and sled, pitch/depth control computer and cutting head. Basically, the lathe (Figure 21.6a) consists of a heavy, shock-mounted steel base (a). A weighted turn-table (b) is isolated from the base by an oil-filled coupling (c), which reduces wow and flutter to extremely low levels. The lathe bed (d) allows the cutter suspension (e) and the cutter head (f) to be driven by a screw feed that slowly moves the record mechanism along a sled in a motion that’s perpendicular to the turntable.

Cutting Head

The cutting head translates the electrical signals that are applied to it into mechanical motion at the recording stylus. The stylus gradually moves in a straight line toward the disc’s center hole as the turntable rotates, creating a spiral groove on the record’s surface. This spiral motion is achieved by attaching the cutting head to a sled that runs on a spiral gear (known as the lead screw), which drives the sled in a straight track.

FIGURE 21.6

The disc-cutting lathe: (a) lathe with automatic pitch and depth control. (Courtesy of Paul Stubblebine Mastering and Michael Romanowski Mastering, San Francisco, CA, www.paulstubblebine.com and www.michaelromanowski.com); (b) simplified drawing of a stereo cutting head.

The stereo cutting head (Figure 21.6b) consists of a stylus that’s mechanically connected to two drive coils and two feedback coils (which are mounted in a perma nent magnetic field) and a stylus heating coil that’s wrapped around the tip of the stylus. When a signal is applied to the drive coils, an alternating current flows through them creating a changing magnetic field that alternately attracts and repels the permanent magnet. Because the permanent magnet is fixed, the coils move in proportion to a field strength that causes the stylus to move in a plane that’s 45º to the left or right of vertical (depending on which coil is being driven).

Pitch Control

The head speed determines the “pitch” of the recording and is measured by the number of grooves, or lines per inch (lpi), that are cut into the disc. As the head speed increases, the number of lpi will decrease, resulting in a corresponding decrease in playing time. Varying the lead screw’s rotation can most commonly change groove pitch by changing the motor’s speed (a common way to vary the program’s pitch in real-time).

The space between grooves is called the land. Modulated grooves produce a lateral motion that’s proportional to the in-phase signals between the stereo channels. If the cutting pitch is too high (causing too many lines per inch, which closely spaces the grooves) and high-level signals are cut, it’s possible for the groove to break through the wall into an adjacent groove (causing overcut) or for the grooves to overlap (twinning). The former is likely to cause the record to skip when played, while the latter causes either distortion or a signal echo from the adjacent groove (due to wall deformations). Groove echo can occur even if the walls don’t touch and is directly related to groove width, pitch and level.

These cutting problems can be eliminated either by reducing the cutting level or by reducing the lines per inch. A conflict can arise here as a louder record will have a reduced playing time, but will also sound brighter, punchier, and more present (due to the Fletcher-Munson curve effect). Because record companies and producers are always concerned about the competitive levels of their discs relative to those that are cut by others, they’re reluctant to reduce the overall cutting level.

The solution to these level problems is to continuously vary the pitch so as to cut more lines per inch during soft passages and fewer lines per inch during loud passages. This is done by splitting the program material into two paths: undelayed and delayed. The undelayed signal is routed to the lathe’s pitch/depth control computer (which determines the pitch needed for each program portion and varies the lathe’s screw motor speed). The delayed signal (which is usually achieved by using a high-quality digital delay line) is fed to the cutter head, thereby giving the pitch/depth control computer enough time to change the lpi to the appropriate pitch. Although longer playing times can be attained by reducing levels and by varying pitch control, many of the pros recommend keeping playing times of a “good sounding” LP to about 18 minutes per side or less.

The LP Mastering Process

Once the mastering engineer sets a basic pitch on the lathe, a lacquer (a flat aluminum disc that’s coated with a film of lacquer) is placed on the turntable and compressed air is used to blow any accumulated dust off the lacquer surface. A chip suction vacuum is started and a test cut is made on the outside of the disc to check for groove depth and stylus heat. Once the start button is pressed, the lathe moves into the starting diameter, lowers the cutting head onto the disc, starts the spiral and lead-in cuts, and begins playing the master production tape. As the side is cut, the engineer can fine-tune any changes to the previously determined console settings. Whenever an analog tape machine is used, a photocell mounted on the deck senses white leader tape between the selections on the master tape and signals the lathe to automatically expand the grooves to produce track bands. After the last selection on the side, the lathe cuts the lead-out groove and lifts the cutter head off the lacquer.

This master lacquer is never played, because the pressure of the playback stylus would damage the recorded soundtrack (in the form of high-frequency losses and increased noise). Reference lacquers (also called reference acetates or simply acetates) are cut to hear how the master lacquer will sound.

After the reference is approved, the record company assigns each side of the disc a master (or matrix) number that the cutting room engineer scribes between the grooves of the lacquer’s ending spiral. This number identifies the lacquer in order to eliminate any need to play the record, and often carries the mastering engineer’s personal identity mark. If a disc is remastered for any reason, some record companies will retain the same master numbers; others add a suffix to the new master to differentiate it from the previous “cut.”

Vinyl Disc Plating and Pressing

When the final master arrives at the plating plant, it is washed to remove any dust particles and then electroplated with nickel. Once the electroplating is complete, the nickel plate is pulled away from the lacquer. If something goes wrong at this point, the master will be damaged, and the master lacquer must be recut.

The nickel plate that’s pulled off the master (called the matrix) is a negative image of the master lacquer (Figure 21.7). This negative image is then electroplated to produce a nickel positive image called a mother. Because the nickel is stronger than the lacquer disc, several mothers can be made from a single matrix. Since the mother is a positive image, it can be played as a test for noise, skips, and other defects. If it’s accepted, the mother can be electroplated several times, producing stampers that are negative images of the disc (a final plating stage that’s used to press the record).

FIGURE 21.7

The various stages in the plating and pressing process.

The stampers for the two sides of the record are mounted on the top and bottom plates of a hydraulic press. A lump of vinylite compound (called a biscuit) is placed in the press between the labels for the two sides. The press is then closed and heated by steam to make the vinylite flow around the raised grooves of the stampers. The resulting pressed record is too soft to handle when hot, so cold water is circulated through the press to cool it before the pressure is released. When the press opens, the operator pulls the record off the mold and the excess (called flash) is trimmed off after the disc is removed from the press. Once done, the disc’s edge is buffed smooth and the product is ready for packaging, distribution and sales.

PRODUCT DISTRIBUTION

With the rise of Internet music distribution and the steady breakdown of the traditional record company distribution system, bands and individual artists have begun to produce, market and sell their own music on an ever-increasing scale. This concept of the “grower” selling directly to the consumer is as old as the town square produce market. By using the global Internet economy, independent distribution, fanzines, live concert sales, etc., savvy independent artists are taking matters into their own hands by learning the inner workings of the music business. In short, artists are being forced to take business matters more seriously in order to reap the fruits of their labor and craft—something that has never been and never will be an easy task.

Online Distribution

On the subject of online distribution, besides the important fact that an artist’s music has the potential to reach a large fan base, the best part about downloadable media is that there’s no expensive physical media to manufacture and distribute. Gone are the days when you have to give up a closet or area in your basement for storing CDs and LPs. However, the flipside to this is that the artist will need to research and understand their online distribution options, needs and legal responsibilities before signing to a download service.

UPLOADING TO STARDOM

In this day of surfing and streaming media off the Web, it almost goes without saying that the web has become the most important and effective marketing tool for the musician and labels alike. It allows us to cost-effectively upload and promote our songs, projects, promotional materials, touring info and liner notes and distribute them to mass audiences. However, long before the recording and mix phases of a project have been completed (assuming that you’re also doing your business and promotion homework), the next and possibly most important steps to take are:

■ Target your audience: Who are your fans and what is your message (music, communication style, personal brand)?

■ Create a “presence”: Develop a web marketing and music distribution presence and then find the best ways to get that message out to your fans.

■ Develop a social network system to interact with the fans (if that’s what you want).

■ Broadcast your music: Using terrestrial radio or TV, podcasts, YouTube videos, you can expand your audience reach.

■ Perform live: This can be done on the stage or on the web (in a live or YouTube live-cast platform).

■ Distribute your music: Using a carefully chosen online distributor you can create a sales presence that is uniquely your own, or you could use a single distributor that releases your music to most or all of the major online distribution networks—or both. In this day and age, it’s easy to make the world your musical oyster.

■ BUT—the trick is to get heard above the millions of others that are also vying for everyone’s attention—that’s the hard part that requires talent, luck, tenacity and connections.

From a technical standpoint, mastering for the Internet can either be complicated; requiring professional knowledge and experience, or it can be a simple and straightforward process that can be carried out from any computer. It’s a matter of meeting the level of professionalism and development that’s required by you and your audience’s needs.

Generally, it’s a good idea to keep the quality as high as possible. Most online distribution companies will offer guidelines for accepted sound file, sample and bitrate types and/or will re-encode the sound file to match their own internal codec rates and format (making it a simple easy-to-upload process).

One of the more important considerations that should be made before you start the upload process is to decide upon the proper metadata for your project, songs or song. Metadata (or tagged information) is the inputting of media information relating to:

■ Project Name

■ Artist Name

■ Song Names

■ Music Genre

■ Publisher Info

■ Copyright Info, etc.

It’s important that you enter this data correctly and with forethought, as the distribution system will use this information within their search database and for finding your music in their system, on the Web, etc. Quite simply, inaccurate metadata will bury your hard work in the haystack like a proverbial needle (that won’t get played).

BUILD YOUR OWN WEBSITE

If you build it, they will come! This overly simplistic concept definitely doesn’t apply to the web. With an ever-increasing number of dot-whatevers going online every month, expecting people to come to your personal or music site just because it’s there simply isn’t realistic. Like anything that’s worthwhile, it takes connections, persistence, a good product and good ol’-fashioned dumb luck to be seen as well as heard! If you’re selling your music, T-shirts or whatever at gigs, on the streets and to family and friends, cyberspace can help increase sales by making it possible (and even easy) to get your band, music or clients onto several independent music websites that offer up descriptions, downloadable samples, direct sales and a link that goes directly to your main website. Such a site could definitely help to get the word out to a potentially new public—and to help educate your audience about you and your music.

Of course, artists aren’t the only ones that have websites. Most folks in fields involving the crafts have a site; heck, even some studios have sites for their studio pets or mascots. Here are a few general guidelines that help your website work its magic for you and/or your organization.

■ Make your site a central hub: It’s always a good idea to direct your social network friends and fans to your personal or band page. This helps to inform them about your upcoming projects, older ones that are for sale, current goings-on in your personal and professional life, etc.

■ Give it a strong, uncluttered main page: Give your site a simple front page that makes a statement about you and your work. From there, they can dig deeper and be drawn into “all things you.”

■ Keep your site simple and straightforward: Try to make your site navigation easy to use and understand. Don’t use problematic animations or programming that can easily confuse your audience.

■ Make your site personal: Speak directly to your fans: Let your fans know what makes you tick, what you’re up to, as well as what’s happening in your professional life.

■ Keep it up-to-date: Nothing’s worse than going to a site, only to see that there’s been no activity on it. Nothing says “I don’t care” like a neglected site.

THOUGHTS ON BEING (AND GETTING HEARD) IN CYBERSPACE

In the past, there were smaller, separate stores for meats, cheese, candy, etc., and the milk would be delivered to your doorstep. It was all pretty much kept on a smaller, personable scale. Now, in the age of the supermarket, where everything is wholesaled, processed, packaged and distributed to a single clearinghouse there are more options, but the scale is so large that older folks can only shop there with the aid of a motorized shopping cart.

For more than six decades, the music industry has largely worked on a similar principle: Find artists who’ll fit into an existing marketing formula (or, more rarely, create a new marketing image), produce and package them according to that formula and put tons of bucks behind them to get them heard and distributed, and then put them on all of the Mom ‘n’ Pop Music store shelves everywhere. This was not a bad thing in and of itself; however, for independent artists the struggle has been, and continues to be, one of getting themselves heard, seen and noticed—without the aid of the well-oiled mega-machine. With the creation of cyberspace, not only are established record industry forces able to work their way onto your desktop screen (and into your multimedia speakers), but independent artists now also have a huge medium for getting heard. Through the creation of dedicated websites, search engines, links from other sites, and independent music dot-coms, as well as through creative gigging and marketing, new avenues have begun to open up for the web-savvy independent artist (Figure 21.8). The only trick is to connect with you fans, so you can get noticed in that great music supermarket.

FIGURE 21.8

Getting the artist’s work out to the masses is hard work. Here’s my chance to put my best foot (or music site www.davidmileshuber.com) forward. Moral of the story? Never pass up an opportunity!

STREAMING

Although music downloads are one of the strongest-growing markets in the music industry, another market that’s also showing huge growth potential is the online music and media streaming market. Streaming refers to the concept that music and video content exists only in the cloud (on web servers) and is available for listening by the subscriber (for a monthly fee) on a 24/7 basis. The major difference here is that the listener has no ownership over the music and can’t download the media files directly; we’re simply licensed to access and listen to them.

Companies like Pandora, Amazon Prime and Apple have been working to perfect a business model that allows the customer to feel comfortable with paying a monthly fee for access to their music database. One of the greatest and highly publicized problems is the notoriously low fees that are paid out to musicians and music labels for the use of their content.

As with downloadable distribution, it’s important that the music content’s metadata be correctly thought out and entered—in fact, it’s the metadata aspect of the music that allows the streaming process to work in the first place. Again, inaccurate metadata will bury your hard work in the haystack like a proverbial needle (that simply won’t get played).

FREE STREAMING SERVICES

Of course, in this day and age when music is literally and inescapably everywhere, the most popular streaming service is free—of course, we’re talking about YouTube. Known for its vast resource library of video material, YouTube is also one of the most (if not the most) popular ways for fans to connect with their favorite artist or group’s music. How much does the artist get paid for these free online efforts? Well nothing, or practically nothing.

Internet Radio

Due to the increased bandwidth of many Internet connections and improvements in audio streaming technology, many of the world’s radio stations have begun to broadcast on the web. In addition to offering a worldwide platform for traditional radio listening audiences, a large number of corporate and independent web radio stations have begun to spring up that can help to increase the fan and listener base of musicians and record labels. Go ahead, get on the web and listen to your favorite Mexican station, catch the latest dance craze from Berlin, or chill to reggae rhythms streaming on an island breeze.

MONEY FOR NOTHIN’ AND THE CHICKS …

As you might expect, making a living in today’s online marketplace is as difficult as it ever was. Sure, it’s easy to get your material out there, but getting heard, seen and surfed above the digital fray requires a great deal of knowledge, dedication, artistry, time and money. When you factor in the reality that income on sales for digital streaming can be relatively meager (this is often true with digital download, as well) it’s no wonder that most popular artists turn to touring, merchandise and promotional associations to keep their business afloat. Even with a huge fan base and media buying/streaming public, it can be a difficult business that requires a great deal of savvy and determination.

Legal Issues

Of course, the subject of legal rights is way beyond the scope of this book, but in this day and age of self-publishing and distribution, it’s definitely worth a mention.

Obviously, the first place to begin diving into the complex and (more often than not) misunderstood subject of music law is by researching the topic on the web and by reading any number of books that are out on the subject. Keep in mind that any info in this book and within any other printed materials on the subject will simply be an opinion and guide. Each artist has his or her own specific legal needs and requirements that can range from being simple (with answers that are stated in easy-to-understand terms) to extremely complex (having twists and turns that can send the most seasoned music executive to the local pub for lubrication).

This last sentence hints at the question about whether or not you need a music lawyer. Again, it depends upon the situation and your specific needs. If you’re uploading your own self-published music into a distribution service and the terms are fairly straightforward, then you will want to take the time to carefully read the site’s fine print, so as to see if there are any pitfalls or snags that might jeopardize your ownership of the publishing rights or other unforeseen events. In this case, you could be just fine researching this legal fine print on your own, with the help of the web and possibly with trusted advice. If things are more complicated, for example, if a record label will be acting as the publisher and the music’s “writer” percentage is split between the band, the lyricist and the producer, then, you’d definitely be wise to sit down with a trusted legal source to hammer out the details that are equitable and free of confusion. In any case, care and time should “always” be taken before signing your name on the dotted line.

ROYALTIES AND OTHER BUSINESS ISSUES

In this “business” of music, one of the goals is to get paid for your hard-earned work. With the added complexities of having so many options for getting an artist’s music out to the world, come the added complexities for calculating, comprehending and collecting the cash. Again, an exhaustive overview of the topic of the music business is far beyond the scope of this book. Fortunately, many books and on-line resources have been written about “The Biz.” However, care must be exercised and often counsel (which can come in many forms) can be sought to help guide you through these enticing and perilous waters. As always, caveat emptor!

Let’s start here:

■ If you are the writer of an original composition and have not signed with a publishing company then you own the publishing (and all rights) to that composition.

■ If you have signed with a publishing company (one that you or the band hire to “hopefully” take care of the everyday inner working of collecting funds and running your business, while you’re busy making and performing music), then the publishing rights to a composition (and thus the paid out funds) will traditionally be split between the writer and the publishing company 50/50.

■ The “Writer” can be a single artist, singer/songwriter, members of a band (equal split), a single member of a band (possibly the one who originally wrote the song) or it can be shared between the lyricist/composer—in short, it is open to be defined in any way that the production team sees fit.

■ A contract is a written legal agreement that can also be written in almost any way—it is always negotiable before it is executed (signed). If there are parts that do not serve your needs and cannot be agreed upon, you probably should seek counsel and think twice (or more times) before signing.

OWNERSHIP OF THE MASTERS

If you are the artist/composer/chief-bottle-washer of a project and are not signed to a publisher, then you are the owner of your recordings. Once you pass through the gates into the realm of dealing with music publishers and record labels, this can change. Contracts can be worded in such ways that the actual ownership of the “phonorecord”, that’s to say the actual recorded production, can be transferred to that entity for a specified period or forever. In these situations, you might want to read the print “very” carefully and/or seek counsel.

REGISTERING YOUR WORK

Regarding copyright ownership, the truth is, that once you’ve written or recorded an original music work, you then own the copyright, however, unless this work is registered with the Library of Congress, it will be difficult to actually prosecute and seek damages from someone who you know has copied your music.

Copyrighting your music with the Library of Congress can now be done online using their eco online registration system (http://www.copyright.gov/eco) and can involve one of two submission forms:

Form SR

Form SR (http://copyright.gov/forms/formsr.pdf) is used for registration of published or unpublished sound recordings, meaning that you are using this form to register the “phonorecord” or the actual recorded production as it exists in physical or downloadable media form.

Form PA

Form PA (http://copyright.gov/forms/formpa.pdf) is used to register published or unpublished works of the performing arts. In the Library’s words: “This class includes works prepared for the purpose of being “performed” directly before an audience or indirectly “by means of any device or process.” Works of the performing arts include: (1) musical works, including any accompanying words; (2) dramatic works, including any accompanying music; (3) pantomimes and choreographic works; and (4) motion pictures and other audiovisual works.

COLLECTING THE $$$

Ahhh, the business side of the industry. Being and staying on top of collecting funds for you, your band or your represented artist isn’t always easy or straightforward, to say the least.

Let’s start here:

■ Direct sales to your fans over a website or at a performance can put $$$ directly into your or the band’s account—very nice.

■ Upon uploading your or your band’s music to a music download service or aggregator (distributor to multiple download services), this company will collect information as to how you will get paid (i.e., PayPal, direct deposit, etc.). This is (or should be) fairly straightforward. Care should be taken to read the percentages and how often these proceeds will be paid out.

■ Once the recording is made and is released to the public, then registration with a performance rights organization might be in order. PRO’s such as ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), BMI (Broadcast Music Inc.) and SESAC (Society of European Stage Authors and Composers) can be found in the U.S. and are used to collect royalties from music that is paid on terrestrial radio stations, restaurants, retail stores and the like.

■ Soundexchange is a performance rights organization that collects royalties from music that is played over satellite and Internet radio, cable TV and spoken word recordings.

■ It should be noted that companies (such as CD Baby PRO and TuneCore) can actually help with signup and collections from several of the above-mentioned organizations, making the process easier for individuals who want to follow these collection avenues.

From the above, it’s easy to see that the task of getting paid for your music is not always a simple task. Many subscribe to the “multiple trickles from many sources” concept, which holds to the idea that by subscribing to these (and other sources), the payment returns will be small, but they will come in from numerous sources in many ways to add up to a sum that could be worth it.

Further Reading

Again, the information in this chapter is simply meant as an introduction. So much information exists on the subject of product manufacture and (even more so) on the distribution and business of music, that I urge you to dig deeper, so as to gain a better understanding and your own personal “edge” on the ever-changing landscape of the music business.