CHAPTER 4

Selecting and Using Lenses for the Nikon D7000

The choice of lenses today is much more vast than it was just as little as five years ago. With the advent of dSLRs and the DX sensor format, most camera and lens manufacturers quickly realized that the standard focal lengths being used for traditional film SLR cameras were not quite adequate. The demand for true wide-angle lenses was great and the increasing resolution of sensors led lens manufacturers to come up with new lens designs optimized for the digital era. This has benefited today's digital photographers because lenses today are truly the world's best and are affordable. With the multitude of lenses available today, selecting one can be a daunting task. This chapter gives you some background on the different types of lenses available.

The ability to use a variety of lenses is one of the main advantages of using a dSLR camera.

Intro to Lenses

A lens is one of the most important parts of a photographer's kit, arguably more important than the camera body itself because a good lens usually outlives the camera body — especially in a day and age when camera bodies are upgraded once a year or more. A lot of my lenses have been with me for more than a decade, while I've been through about a dozen camera bodies.

There are many different types of lenses, and each type allows you to portray your subjects in a different manner. One of the cool things about photography is that your lens choice enables you to show your subjects and surroundings in a way that's just not possible with the human eye. Some people will argue that photography allows you to render a scene realistically so it can be remembered as it was, but I think photography has endured because you can not only realistically render the scene, but also distort that reality with your lens choice.

Nikon Lens Compatibility

Although Nikon has been manufacturing lenses for many decades, with the D7000, you can use almost every Nikon lens made since about 1977, albeit some lenses will have limited functionality. In 1977, Nikon introduced the Auto-Indexing (AI) lens. Auto-Indexing allows the aperture diaphragm on the lens to remain wide open until the shutter is released; the diaphragm then closes down to the desired f-stop. This allows maximum light to enter the camera, which makes focusing easier. You can also use some of the earlier lenses, known now as pre-AI, but most need some modifications to work with the D7000.

Nikon's early lenses are manual focus though you can still use other modern features such as the camera's light-metering system. However, some advanced features of the metering system, such as 3D Color Matrix Metering and Balanced Fill-Flash, will not function.

In the 1980s, Nikon started releasing AF lenses. Many of these lenses are very high quality and cost less than their 1990s counterparts, the AF-D lenses. The main difference between the lenses is that the D lenses provide the camera with distance information based on the focus of the subject. These lenses focus by using a screw-type drive motor that's typically found inside the camera body (the D7000 has a screw drive motor). During this time while Nikon was refining its AF motor, many of the super-telephoto lenses remained MF (manual focus). Nikon fitted these lenses with a CPU for the lens to convey information with the camera body. These are known as AI-P lenses.

![]() Some lower-level Nikon cameras have had the screw-type drive motor removed. The D40, D60, and D5000 are a few examples.

Some lower-level Nikon cameras have had the screw-type drive motor removed. The D40, D60, and D5000 are a few examples.

More recently, Nikon has been producing its line of AF-S lenses. These lenses have a built-in Silent Wave Motor. The AF-S motor allows the lenses to focus much more quickly than the traditional screw-type lenses and also allows the focusing to be ultra-quiet. Most of these lenses are also known as G-type lenses and lack a manual aperture ring. The aperture is controlled by using the Sub-command dial on the camera body. A few years ago, only the very expensive pro lenses had the Silent Wave Motor. Nikon now offers this in even the entry-level lenses.

To date, Nikon offers about 30 AF-S lenses. These lenses range from a super-wide 10-24mm zoom lens all the way up to a 600mm super-telephoto lens. Most of the AF-S lenses are zoom lenses, but Nikon does offer a few fixed focal-length lenses. These fixed focal-length, or prime, lenses are mostly in the telephoto to super-telephoto range, with the exceptions being the 35mm f/1.8, 50mm f/1.4G, and 60mm f/2.8G macro lens. Nikon's AF-S lenses range in price from around $150 for the 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 to almost $10,000 for the 600mm f/4 with VR, so there's an AF-S lens available whatever your budget may be.

Deciphering Nikon's Lens Codes

When shopping for lenses, you may notice all sorts of letter designations in the lens name. For example, the kit lens is the AF-S DX Nikkor 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR. So, what do all those letters mean? Here's a simple list to help you decipher them:

- AI/AIS. These are Auto-Indexing lenses that automatically adjust the aperture diaphragm down when the Shutter Release button is pressed. All lenses made after 1977 are Auto-Indexing, but when referring to AI lenses, most people generally mean the older manual focus (MF) lenses.

- E. These lenses are Nikon's budget series lenses, made to go with the lower-end film cameras, such as the EM, FG, and FG-20. Although these lenses are compact and are often constructed with plastic parts, some of them, especially the 50mm f/1.8, are of quite good quality. These lenses are also manual focus only.

- D. Lenses with this designation convey distance information to the camera body to aid in metering for exposure and flash.

- G. These are newer lenses that lack a manually adjustable aperture ring. You must set the aperture on the camera body. These lenses also convey distance information to the camera body.

- AF, AF-D, AF-I, and AF-S. All these lens codes denote that the lens is an autofocus (AF) lens. The AF-D represents a distance encoder for distance information, the AF-I indicates an internal focusing motor type, and the AF-S indicates an internal Silent Wave Motor.

- AI-P. This designates a manual focus lens that has a CPU chip.

- DX. This lets you know the lens was optimized for use with Nikon's DX-format sensor. The DX designation is explained in depth in the next section.

- VR. This code denotes that the lens is equipped with Nikon's Vibration Reduction image stabilization system.

- ED. This indicates that some of the glass in the lens is Nikon's Extra-Low Dispersion (ED) glass, which means the lens is less prone to lens flare and chromatic aberrations. Chromatic aberrations can be seen as color fringing around the edges of a high contrast subject. They are usually more pronounced at the edges of the images.

- Micro-Nikkor. This is Nikon's designation for macro lenses that allow close-up focusing.

- IF. IF stands for internal focus. The focusing mechanism is inside the lens, so the front of the lens doesn't rotate or move in and out when focusing. This feature is useful when you don't want the front of the lens element to move — for example, when you use a polarizing filter. The internal focus mechanism also allows for faster focusing.

- DC. DC stands for Defocus Control. Nikon only offers a couple of lenses with this designation. These lenses make the out-of-focus areas in the image appear softer by using special lens elements to add spherical aberration. The parts of the image that are in focus aren't affected. Currently, the only Nikon lenses with this feature are the 135mm f/2 and the 105mm f/2. Both are considered portrait lenses.

- N. On some of Nikon's newest professional lenses, you may see a large, golden N. This means that the lens has Nikon's Nano Crystal Coating, which is designed to reduce flare and ghosting.

4.1 Nikon lenses have a veritable alphabet soup of designations on them. These lens codes designate that a Silent Wave Motor is on an 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 lens with no aperture ring, the lens has Extra-Low Dispersion lens elements, and it is meant for use on a DX camera.

DX Crop Factor

Crop factor is a ratio that describes the size of a camera's imaging area as compared to another format; in the case of SLR cameras, the reference format is 35mm film.

SLR camera lenses were designed around the 35mm film format. Photographers use lenses of a certain focal length to provide a specific field of view. The field of view, also called the angle of view, is the amount of the scene that's captured in an image. This is usually described in degrees. For example, when you use a 16mm lens on a 35mm camera, it captures almost 180° of the scene, which is quite a bit. Conversely, when you use a 300mm focal length, the field of view is reduced to a mere 6.5°, which is a very small part of the scene. The field of view is consistent from camera to camera because all SLRs use 35mm film, which has an image area of 24mm × 36mm.

With the introduction of digital SLRs, the sensor was designed to be smaller than a frame of 35mm film to keep costs down because the sensors are more expensive to manufacture. This sensor size was called APS-C or, in Nikon terms, the DX-format. The lenses that are used with DX-format dSLRs have the same focal length they've always had, but because the sensor doesn't have the same amount of area as the film, the field of view is effectively cropped. This causes the lens to provide the field of view of a longer focal lens when compared with 35mm film images.

4.2 This image was shot with a 28mm lens on a D700 FX camera. The amount of the scene that would be captured with the same lens on a DX camera like the D7000 appears inside the red square.

Fortunately, the DX sensors are a uniform size, so you can refer to this standard to determine how much the field of view is reduced on a DX-format dSLR with any lens. The digital sensors in Nikon DX cameras have a 1.5X crop factor, which means that to determine the equivalent focal length of a 35mm or FX camera, you simply have to multiply the focal length of the lens by 1.5. Therefore, a 28mm lens provides an angle of coverage similar to a 42mm lens; a 50mm is equivalent to a 75mm; and so on.

![]() An easy way to figure out crop factor without a calculator is simply to halve the focal length number and then add that number to the focal length. For example, half of 50mm is 25mm, so add 25mm to 50mm and you get 75mm.

An easy way to figure out crop factor without a calculator is simply to halve the focal length number and then add that number to the focal length. For example, half of 50mm is 25mm, so add 25mm to 50mm and you get 75mm.

When dSLRs were first introduced, all lenses were based on 35mm film. The crop factor effectively reduced the coverage of these lenses, causing ultrawide-angle lenses to perform like wide-angle lenses, wide-angle lenses to perform like normal lenses, normal lenses to provide the same coverage as short telephotos, and so on. Nikon has created specific lenses for dSLRs with digital sensors. These lenses are known as DX-format lenses. The focal length of these lenses was shortened to fill the gap to allow true super-wide-angle lenses. These DX-format lenses were also redesigned to cast a smaller image inside the camera so that the lenses could actually be made smaller and use less glass than conventional lenses. The byproduct of designing a lens to project an image circle to a smaller sensor is that these same lenses can't be used effectively with the FX-format and can't be used at all with 35mm film cameras (without severe vignetting) because the image won't completely fill an area the size of the film or FX sensor.

There is an upside to this crop factor: Lenses with longer focal lengths now provide a bit of extra reach. A lens set at 200mm now provides the same amount of coverage as a 300mm lens, which can give you a great advantage with sports and wildlife photography or when you simply can't get close enough to your subject.

Another advantage with DX lenses is that because DX lenses are smaller, they can be manufactured for less, which in turn means DX lenses are less expensive than their full-frame counterparts.

Detachable Lenses

Although your D7000 may come with a kit lens — the 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G VR — one advantage to owning a dSLR is the ability to use detachable lenses. This allows you to change your lens to fit the specific photographic style or scene that you want to capture. After a while, you may find that the kit lens doesn't meet your needs and you want to upgrade. Nikon dSLR owners have quite a few lenses from which to choose, all of which benefit from Nikon's expertise in the field of lens manufacturing.

One of the great things about photography is that through your lens choice, you can show things in a way that the human eye can't perceive. The human eye is basically a fixed-focal-length lens. We can only see a certain set angular distance. This is called our field of view (or angle of view). Our eyes have about the same field of view as a 35mm lens on your D7000. Changing the focal length of your lens, whether by switching lenses or zooming, changes the field of view, enabling the camera to 'see' more or less of the scene that you're photographing. Changing the focal length of the lens allows you to change the perspective of your images. In the following sections, I discuss the different types of lenses and how they can influence the subjects that you're photographing.

Kit Lenses

Some Nikon D7000 cameras come paired with Nikon's 18-105mm f/3.5-5.6G VR AF-S DX lens, which was first offered coupled with the D90. This lens covers the most commonly used focal lengths for everyday photography. The 18mm setting covers the wide-angle range, and zooming all the way out to 105mm gives you a decent telephoto setting, allowing you to get close-up photos of subjects that may not be very close. The kit lens also has Nikon's Vibration Reduction (VR) feature. This feature allows you to hand hold the camera at slower shutter speeds without worrying about image blur that can be caused by camera shake.

The 18-105mm VR lens has received many good reviews. The optics give you sharp images with good contrast when stopped down a bit. However, when you are shooting wide open, the images can appear a little soft around the corners. It should be said here that all lenses have a 'sweet spot,' or a range of apertures at which they appear sharpest. With most lenses, this sweet spot is usually one or two stops from the maximum aperture. For the kit lens, the sweet spot is around f/8 to f/11. Another thing to be aware of is that as the aperture gets smaller than f/16, you also may lose some sharpness due to the diffraction of the light by the aperture blades.

![]() Stopping down refers to making the aperture smaller, and opening up refers to making the aperture larger.

Stopping down refers to making the aperture smaller, and opening up refers to making the aperture larger.

Although Nikon offers many very high-quality professional lenses, the D7000 kit lenses are very good performers for their price range, and they offer some advantages when paired with the D7000 that even some of Nikon's more expensive lenses don't. These advantages include the following:

- Low cost. The 18-105mm VR lens costs less than $300, while the 55-200mm VR lens comes in at around $250. The 18-200mm VR lens retails for around $750. Buying both the 18-55mm and 55-200mm VR lenses can save you around $200.

- Excellent image quality. These lenses offer very high quality for the price. They offer aspherical lens elements, which help to eliminate distortion, and Nikon's Super Integrated Coating on the lens helps to ensure accurate color and reduce lens flare. These lenses have been praised by professional and amateur reviewers alike. They are uncommonly sharp for a lens in this price range.

- Compact size. Being that they are designed specifically for dSLR cameras, these lenses are small in size and super light. They are great lenses for everyday use or long trips where you don't want a lot of gear weighing you down.

- VR. Vibration Reduction is a very handy feature, especially when you are working in low-light situations or using a long focal length. It can allow you to hand hold your camera at slower shutter speeds than you can with standard lenses.

4.3 The D7000 with the 18-105mm kit lens

Zoom Versus Prime Lenses

The debate over whether to use zoom or prime lenses has been a hot topic for many years. In the past eight years or so, lens technology has grown by leaps and bounds, and zoom lenses are just about as sharp as primes or, in the case of the Nikkor 14-24mm f/2.8, even sharper than most primes. Some photographers prefer primes, and some prefer zooms. It's largely a personal choice, and there are some things to consider.

Understanding zoom lenses

A zoom lens, such as the AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm, is a lens that has multiple optical elements that move within the lens body; this allows the lens to change focal length, and therefore field of view, which is how much of the scene you can see at any given focal length.

One of the main advantages of the zoom lens is its versatility. You can attach one lens to your camera and use it in a wide variety of situations.

There are a few things to consider when buying zoom lenses (or upgrading from one you already have), including variable aperture, depth of field, and quality.

Variable aperture

One of the major issues when buying a consumer-level lens such as the 18-105mm VR lens is that it has a variable aperture, which means that as you zoom in on something when shooting wide open or closed down to the minimum aperture, the aperture opening gets smaller, allowing less light to reach the sensor and causing the need for a slower shutter speed or higher ISO setting. Most high-end lenses have a constant aperture all the way through the zoom range. In daylight or brightly lit situations, this may not be a factor, but when shooting in low light, this can be a drawback. Although the VR feature helps when shooting relatively still subjects, moving subjects in low light are blurred.

If you do a lot of low-light shooting of moving subjects, such as concert photography, you may want to look into getting a zoom lens with a wider aperture such as f/2.8. These are fast aperture pro lenses and usually cost quite a bit more than your standard consumer zoom lens. The lens I use most when photographing action in low light is the Nikkor 17-55mm f/2.8; this lens allows me to use an ISO of about 800 (keeping the noise levels low) and has relatively fast shutter speeds to freeze the motion of the subject.

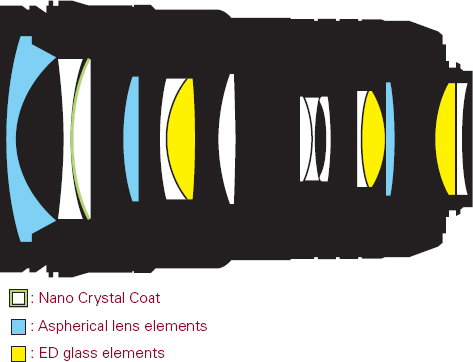

4.4 Lenses are made up of many different glass elements. This is a diagram of the inside of a Nikon 24-70mm f/2.8 lens.

Depth of field

Another consideration when buying a consumer-level zoom lens is depth of field. For example, the 18-55mm lens, because the aperture is inherently smaller and grows smaller as it zooms in, gives you more depth of field at all focal lengths than a lens with a wider aperture. If you are shooting landscapes, this may not be a problem, but if you are getting into portrait photography, you may want a shallower depth of field; therefore, a lens with a wider aperture is probably what you want.

Quality

In order to make consumer lenses like the 18-105mm VR affordable, Nikon manufactures them mostly out of a composite plastic. Although the build quality is pretty good, the higher-end lenses have metal lens mounts and some have metal alloy lens bodies. This makes them a lot more durable in the long run, especially if you are rough on your gear like I sometimes am. Conversely, the plastic bodies of the consumer lenses are much smaller and lighter than their pro-level counterparts. This is a great feature when you are traveling or if you want to pack light. If I'm going on a quick day trip, more often than not, I'll just grab my D7000 kit and go. It's more compact and much lighter than my other cameras and lenses and I appreciate the small size.

Understanding prime lenses

Before zoom lenses were available, the only option a photographer had was using a prime lens, also called a fixed-focal-length lens. Because each lens is fixed at a certain focal length, when the photographer wanted to change how much of the scene is in the image, he had to either physically move farther away from or closer to the subject, or swap out the lens with one that had a focal length more suited to the range.

The most important features of the prime lens are that they can offer a faster maximum aperture, are generally far lighter, and usually cost much less (ultra-fast wide-angle primes, such as the 24mm f/1.4, are the exception). Normal focal length prime lenses, such as the 35mm f/1.8, aren't very long, so the maximum aperture can be faster than it is with zoom lenses. Most standard prime lenses also require fewer lens elements and moving parts, so the weight can be kept down considerably, and because there are fewer elements, the overall cost of production is less; therefore, you pay less.

You might say, ‘Well, if I can buy one zoom lens that encompasses the same range as four or five prime lenses, then why bother with prime lenses?’ While this may sound logical, there are a few reasons why you might choose a prime lens over a zoom lens.

- Sharpness. Prime lenses don't require as many lens elements (pieces of glass) as zoom lenses do, and this means that prime lenses are almost always sharper than consumer-level zoom lenses. Although it has to be said, with the advances in machining and lens manufacturing, high-end zoom lenses are on par with primes for sharpness.

- Speed. Some prime lenses have faster apertures than any available zooms. The fastest zoom lens you can find is f/2.8. The 35mm f/1.8 is about 1 1/3 of a stop faster than a zoom, and an f/1.4 lens is a full 2 stops faster.

4.5 The Nikkor 35mm f/1.8G AF-S fixed-focal-length prime lens is one of the best bargains in the fast prime lenses arena.

Nikon now offers a pretty good selection of AF-S prime lenses. Currently, the AF-S prime lens lineup consists of the 24mm f/1.4, 35mm f/1.8, 35mm f/1.4, 50mm f/1.4, 85mm f/1.4, 60mm f/2.8 macro, 85mm f/3.5 macro, and 105mm f/2.8 VR macro. For telephoto primes, you have the 200mm, 300mm, 400mm, 500mm, and 600mm telephoto lenses. Unfortunately, apart from the 35mm f/1.8, which can be purchased for about $200, most of these lenses are quite expensive. For a super fast lens, the 50mm f/1.4 is a good value for about $500, and for a macro lens, consider the 85mm f/3.5, which can be found for right around $500 as well.

Wide-angle and Ultrawide-angle Lenses

Wide-angle lenses, as the name implies, provide a very wide angle of view of the scene you're photographing. Wide-angle lenses are great for photographing a variety of subjects, but they're especially excellent for subjects such as landscapes and group portraits, where you need to capture a wide area of view.

The focal-length range of wide-angle lenses starts out at about 10mm (ultrawide) and extends to about 24mm (wide angle). Most wide-angle lenses on the market today are zoom lenses, although there are quite a few prime lenses available. Wide-angle lenses are generally rectilinear, meaning that there are lens elements built in to the lens to correct distortion; this way, the lines near the edges of the frame appear straight. Fisheye lenses, which are also a type of wide-angle lens, are curvilinear; the lens elements aren't corrected, resulting in severe optical distortion. I discuss fisheye lenses later in this chapter.

In recent years, lens technology has grown rapidly, making high-quality ultrawide-angle lenses affordable. In the past, ultrawide-angle lenses were rare, prohibitively expensive, and out of reach for most amateur photographers. These days, it's very easy to find a relatively inexpensive ultrawide-angle lens; for example you can find a Sigma 10-24mm lens for under $500. Most wide-angle zoom lenses run the gamut from ultrawide to wide angle. Some of the ones that work with the D7000 include the following:

- Nikkor 10-24mm f/3.5-4.5. This is one of Nikon's newer ultrawide DX zooms. The 10-24mm was specifically designed for DX cameras. This lens gives you a very wide field of view, and it's small and well built with little distortion. The AF-S motor allows it to focus perfectly with the D7000.

- Sigma 10-20mm f/3.5. When it comes to third-party lenses, I prefer Sigma lenses. They have superior build quality and their Hyper-Sonic Motor (HSM), which is similar to Nikon's Silent Wave AF-S motor, allows this lens to autofocus with the D7000. This lens is not as sharp as the Nikon mentioned previously and it has a reduced range on the long end, but it's much cheaper. You may not even miss the longer range at all, given it's most likely covered by one of your other lenses, such as the 18-55mm kit lens. This lens also has a constant aperture, which gives it a leg up on the competition. You can save about $200 by buying the variable aperture f/4-5.6 version.

- Tokina AT-X 124 AF Pro DX II. This is a 12-24mm f/4 wide-angle lens. This is Tokina's updated version of the original 12-24mm f/4, which is a very sharp and relatively inexpensive lens.

Sigma also offers a 12-24mm lens. It's built like a tank and has an HSM motor. The Sigma is also useable with Nikon FX cameras, which may be something to consider if you're planning to upgrade to FX sometime in the future.

Deciding when to use a wide-angle lens

You can use wide-angle lenses for a broad variety of subjects, and they're great for creating dynamic images with interesting results. Once you get used to seeing the world through a wide-angle lens, you may find that your images start to be more creative, and you may look at your subjects differently. There are many considerations when you use a wide-angle lens. Here are a few:

- Greater depth of field. Wide-angle lenses allow you to get more of the scene in focus than you can when you use a midrange or telephoto lens at the same aperture and distance from the subject.

- Wider field of view. Wide-angle lenses allow you to fit more of your subject into your images. The shorter the focal length, the more you can fit in. This can be especially beneficial when you shoot landscape photos where you want to fit an immense scene into your photo.

- Perspective distortion. Using wide-angle lenses causes things that are closer to the lens to look disproportionately larger than things that are farther away. You can use perspective distortion to your advantage to emphasize objects in the foreground if you want the subject to stand out in the frame.

- Handholding. At shorter focal lengths, it's possible to hold the camera steadier than you can at longer focal lengths. At 14mm, it's entirely possible to hand hold your camera at 1/15 second without worrying about camera shake.

- Environmental portraits. Although using a wide-angle lens isn't the best choice for standard close-up portraits, wide-angle lenses work great for environmental portraits, where you want to show a person in her surroundings.

Wide-angle lenses can also help pull you into a subject. With most wide-angle lenses, you can focus very close to the subject. This helps you create an intimate image while incorporating the perspective distortion that wide-angle lenses are known for. Don't be afraid to get close to your subject to make a more dynamic image. The worst wide-angle images are the ones that have a tiny subject in the middle of an empty area.

Understanding limitations

Wide-angle lenses are very distinctive when it comes to the way they portray your images, and they also have some limitations that you may not find in lenses with longer focal lengths. There are also some pitfalls that you need to be aware of when using wide-angle lenses:

- Soft corners. The most common problem that wide-angle lenses, especially zoom lenses, have is that they soften the images in the corners. This is most prevalent at wide apertures, such as f/2.8 and f/4, and the corners usually sharpen up by f/8 (depending on the lens). This problem is greatest in lower-priced lenses.

4.7 A shot taken with a wide-angle lens can add an interesting perspective to some images. Exposure: ISO 560 (Auto), f/3.5, 1/125 second using a Sigma 10-20mm f/3.5 lens at 10mm.

- Vignetting. This is the darkening of the corners in the image. This occurs because the light that's needed to capture such a wide angle of view must come from an oblique angle. When the light comes in at such an angle, the aperture is effectively smaller. The aperture opening no longer appears as a circle but is shaped like a cat's eye. Stopping down the aperture 1 to 2 stops from the widest setting reduces this effect, and stopping down by 3 stops usually eliminates vignetting altogether.

- Perspective distortion. Perspective distortion is a double-edged sword: It can make your images look very interesting or make them look terrible. One of the reasons that a wide-angle lens isn't recommended for close-up portraits is that it distorts the face, making the nose look too big and the ears too small. This can make for a very unflattering portrait.

- Barrel distortion. Wide-angle lenses, even rectilinear lenses, are often plagued with this specific type of distortion, which causes straight lines outside the image center to appear to bend outward (similar to a barrel). This can be unwanted especially when doing architectural photography. Fortunately, you can use Adobe Photoshop and other image-editing software to fix this problem relatively easily.

Standard or Midrange Lenses

Standard, or midrange, zoom lenses fall in the middle of the focal-length scale. Zoom lenses of this type usually start at a moderately wide angle of around 16-18mm and zoom in to a short telephoto range. These lenses work great for most general photography applications and can be used successfully for everything from architectural to portrait photography. Basically, this type of lens covers the most useful focal lengths and will probably spend the most time on your camera. The 18-105mm kit lens falls into this range.

Here are some of the options for midrange lenses:

- Nikkor 17-55mm f/2.8. This is Nikon's top-of-the-line standard DX zoom lens. It's a professional lens that has a fast aperture of f/2.8 over the whole zoom range and is extremely sharp at all focal lengths and apertures. The build quality on this lens is excellent, as most of Nikon's pro lenses are. The 17-55mm has Nikon's super-quiet and fast-focusing Silent Wave Motor as well as ED glass elements to reduce chromatic aberration. This lens is top-notch all around and is worth every penny of the almost $1,400 price tag.

- Sigma 17-70mm f/2.8-4 OS. This lens is a low-cost alternative to the Nikon 17-55mm that has a variable aperture of f/2.8 on the wide end and f/4 on the long end. You can get this lens for about $450, which is almost one-quarter of the cost of the Nikon 17-55mm and it's much smaller and lighter. It's got Sigma's HSM so it autofocuses quickly and quietly. It's a great walking-around lens for standard shots. This lens also allows you to focus closely on subjects; it's not a true macro lens, but it's close. The optical stabilization (OS) also helps to reduce camera shake blur. Currently, this is my favorite lens because it's relatively fast at all focal lengths and has a macro feature and OS. It does almost everything you need and is incredibly lightweight.

- Tamron SP AF 17-50mm f/2.8 Di-II VC. This pretty good, reasonably priced ($650) constant aperture lens includes Vibration Compensation (Tamron's version of Nikon's VR). The only drawback to this lens is that it uses Tamron's built-in motor (BIM) to focus with the D7000, and it is very slow and loud. Tamron has recently developed a silent motor, which it may integrate into this lens in the near future.

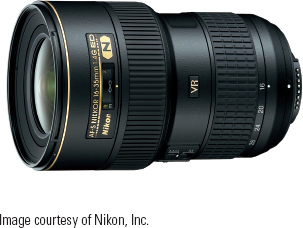

- Nikon 16-35mm f/4 VR. This is one of Nikon's newest offerings. This lens has a constant aperture but it's one step slower than the 17-55 to make it more affordable (although at $1,100 it's still quite pricey in my opinion). It also has the added benefit of VR. Another advantage of this lens is that it's designed for use on FX cameras so if you ever upgrade to a full-frame camera this lens will work perfectly as a wide-angle lens.

A few prime lenses fit into this category: the 28mm, 30mm, and 35mm. These lenses are considered normal lenses for DX cameras in that they approximate the normal field of view of the human eye. They are great all-around lenses. They come with apertures of f/2.8 or faster and can be found for less than $400. The Nikon 35mm is a great lens for under $200 and for ultra low light situations the Sigma 30mm f/1.4 HSM is a great deal for about $440.

Telephoto Lenses

Telephoto lenses have very long focal lengths and are used to get closer to distant subjects. They provide a very narrow field of view and are handy when you're trying to focus on the details of a subject. Telephoto lenses produce a much shallower depth of field than wide-angle and midrange lenses, and you can use them effectively to blur background details to isolate a subject.

Telephoto lenses are commonly used for sports and wildlife photography. The shallow depth of field also makes them one of the top choices for photographing portraits.

As with wide-angle lenses, telephoto lenses also have their quirks, such as perspective distortion. As you may have guessed, telephoto perspective distortion is the opposite of the wide-angle variety. Because everything in the photo is so far away with a telephoto lens, the lens tends to compress the image. Compression causes the background to look too close to the foreground. Of course, you can use this effect creatively. For example, compression can flatten out the features of a model, resulting in a pleasing effect. Compression is another reason why photographers often use a telephoto lens for portrait photography.

4.9 Portrait shot with a telephoto lens. Exposure: ISO 100, f/2.8, 1/640 second with a Nikon 80-200mm f/2.8D lens zoomed to 150mm.

A typical telephoto zoom lens usually has a range of about 55'200mm. If you want to zoom in close to a subject that's very far away, you may need an even longer lens. These super-telephoto lenses can act like telescopes, really bringing the subject in close. They range from about 300mm to about 800mm. Almost all super-telephoto lenses are prime lenses, and they're very heavy, bulky, and expensive.

There are several telephoto prime lenses available. Most of them are pretty expensive, although you can sometimes find some older Nikon primes that are discontinued or used at decent prices. One of these lenses is the 300mm f/4. A couple of relatively inexpensive telephoto primes in the shorter range of 50-85mm are also available. The 50mm is considered a normal lens for FX format, but the DX format makes this lens a 75mm equivalent, landing it squarely in the short telephoto range for use with the D7000. Nikon has an AF-S version of the 50mm f/1.4 and has recently released an 85mm f/1.4.

Most lens manufacturers, Nikon included, offer what's commonly termed a super-zoom, or sometimes called a hyper-zoom. Super-zooms are lenses that encompass a very wide focal length range, from wide angle to telephoto. The most popular of the super-zooms is the Nikon 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 VRII.

These lenses allow you to have a huge focal-length range that you can use in a wide variety of shooting situations without having to switch out lenses. This can come in handy if, for example, you are photographing a landscape scene by using a wide-angle setting, and lo and behold, Bigfoot appears on the horizon. You can quickly zoom in with the super-telephoto setting and get a good close-up shot without having to fumble around in your camera bag to grab a telephoto and switch out lenses, possibly causing you to miss the shot of a lifetime.

Of course, these super-zooms come with a price (figuratively and literally). In order to achieve the great ranges in focal length, you must make some concessions with regard to image quality. These lenses are usually less sharp than lenses with a shorter zoom range and are more often plagued with optical distortions and chromatic aberration. Super-zooms often show pronounced barrel distortion (the bowing out of straight lines in the image) at the wide end and can have moderate to severe pincushion distortion (the bowing in of the straight lines in the image) at the long end of the range. Luckily, you can fix these types of distortions in Adobe Photoshop or other image-editing software.

Another caveat to using these lenses is that they generally have appreciably smaller maximum apertures than zoom lenses with shorter ranges. This can be a problem, especially because larger apertures are generally needed at the long end to keep a high enough shutter speed to avoid blurring from camera shake when handholding. Of course, some manufacturers include some sort of Vibration Reduction feature to help control this problem.

Some popular super-zooms include the Nikon 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 VR (mentioned earlier), the Sigma 18-200mm f/3.5-6.3 with Optical Stabilization, and the Tamron 18-270mm VC f/3.5-5.6. There are also a few super-zoom super-telephoto lenses, including the Nikon 80-400mm and the Sigma 50-500mm.

Here are some of the most common telephoto lenses:

- Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8 VRII. This is Nikon's top-of-the-line telephoto lens. The VR makes this lens useful when photographing far-off subjects handheld. This is a great lens for sports, portraits, and wildlife photography.

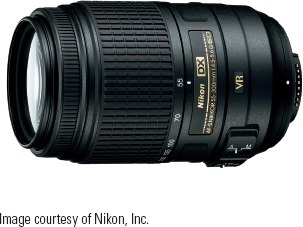

- Nikkor 55-300mm f/4-5.6 VR. This is one of Nikon's newest lenses and is actually a pretty strong performer for its price range. The 55-300mm VR is quite sharp and has only mild barrel distortion issues. It's a great lens with a long reach — excellent for wildlife photography.

- Nikkor 80-200mm f/2.8D AF-S. This is a great, affordable alternative to the 70-200mm VR lens. This lens is sharp and has a fast, constant f/2.8 aperture.

- Sigma 70-200mm f/2.8 HSM. This is a good alternative to the Nikon lenses. The HSM motor allows for autofocus with the D7000 and the lens costs less than half the price of the Nikon 70-200mm, although you do lose VR.

Macro Lenses

A macro lens is a special-purpose lens used in macro and close-up photography. It allows you to have a closer focusing distance than regular lenses, which in turn allows you to get greater magnification of your subject, revealing small details that would otherwise be lost. True macro lenses offer a magnification ratio of 1:1; that is, the image projected onto the sensor through the lens is the exact same size as the actual object being photographed. Some lower-priced macro lenses offer a 1:2 or even a 1:4 magnification ratio, which is one-half to one-quarter of the size of the original object. Although lens manufacturers refer to these lenses as macro, strictly speaking, they are not.

One major concern with a macro lens is the depth of field. When focusing at such a close distance, the depth of field becomes very shallow; it's often advisable to use a small aperture to maximize your depth of field and ensure everything is in focus. Of course, as with any downside, there's an upside: You can also use the shallow depth of field creatively. For example, you can use it to isolate a detail in a subject.

Macro lenses come in a variety of focal lengths, and the most common is 60mm. Some macro lenses have substantially longer focal lengths, which allows for more distance between the lens and the subject. This comes in handy when the subject needs to be lit with an additional light source. A lens that's very close to the subject while you are focusing can get in the way of the light source, casting a shadow.

When buying a macro lens, you should consider a few things: How often are you going to use the lens? Can you use it for other purposes? Do you need AF? Because newer dedicated macro lenses can be pricey, you may want to consider some cheaper alternatives.

The first thing you should know is that it's not absolutely necessary to have an AF lens. When you shoot very close up, the depth of focus is extremely small, so all you need to do is move slightly closer or farther away to achieve focus. This makes an AF lens a bit unnecessary. You can find plenty of older Nikon manual focus (MF) macro lenses that are very inexpensive, and the lens quality and sharpness are still superb.

![]() Several manufacturers make good-quality MF macro lenses. I have a 50mm f/4 Macro-Takumar made for early Pentax screw-mount camera bodies. I bought this lens for next to nothing, and I found an inexpensive adapter that allows it to fit the Nikon F-mount. The great thing about this lens is that it's super sharp and allows me to focus close enough to get a 4:1 magnification ratio, which is 4X life size.

Several manufacturers make good-quality MF macro lenses. I have a 50mm f/4 Macro-Takumar made for early Pentax screw-mount camera bodies. I bought this lens for next to nothing, and I found an inexpensive adapter that allows it to fit the Nikon F-mount. The great thing about this lens is that it's super sharp and allows me to focus close enough to get a 4:1 magnification ratio, which is 4X life size.

Nikon currently offers a few macro lenses under the Micro-Nikkor designation that work well with the D7000. Here are three:

- Nikkor 60mm f/2.8. Nikon offers two versions of this lens — one with a standard AF drive and one with an AF-S version with the Silent Wave Motor. The AF-S version also has the new Nano Crystal Coat lens coating to help eliminate ghosting and flare.

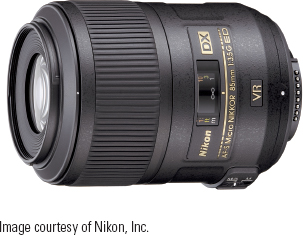

- Nikkor 85mm f/3.5 VR. This is Nikon's latest macro lens offering. This lens is comparable with the 105mm f/2.8 VR, but because it's designed solely for DX cameras, it's smaller, lighter, and less expensive. This is a great choice for serious macro photographers.

- Nikkor 105mm f/2.8 VR. This is a great lens that not only allows you to focus extremely close to your subject but also enables you to back off and still get a good close-up shot. This lens is equipped with VR. This can be invaluable with macro photography because it allows you to hand hold at slower shutter speeds — a necessity when stopping down to maintain a good depth of field. This lens can also double as a very impressive portrait lens.

A couple of third-party lenses that work well with the D7000 include

- Tamron 90mm f/2.8. This lens is highly regarded for its sharpness. It also has a built-in motor, so it will autofocus with the D7000. I initially bought this lens instead of the Nikon 105mm lens, but I quickly returned it. Although it's a good-quality lens, I didn't like the fact that the front element of the lens moves in and out during focusing. This can cause the lens element to hit your subject if you're too close and not careful, possibly damaging the lens. Also, unlike the offerings from Sigma and Nikon, Tamron's built-in focus motor is very loud and very slow.

- Sigma 150mm f/2.8 HSM. This is another lens that is highly regarded for its sharpness. It has fast, quiet focusing with the HSM. It's a great lens.

Fisheye Lenses

Fisheye lenses are ultrawide-angle lenses that aren't corrected for distortion like standard rectilinear wide-angle lenses. These lenses are known as curvilinear, meaning that straight lines in your image, especially near the edge of the frame, are curved. Fisheye lenses have extreme barrel distortion.

Fisheye lenses cover a full 180° area, allowing you to see everything that's immediately to the left and right of you in the frame. You have to take special care to not get your feet in the frame, as is easy to do when you use a lens with a field of view this extreme.

There are two types of fisheye lenses available: regular and circular. A regular fisheye lens fills the whole image plane, resulting in a normal (albeit curved) image. A circular fisheye projects the whole 180° field of view in a circle within the frame, and the corners of the frame remain black.

Fisheye lenses aren't made for everyday shooting, but with their extreme perspective distortion, you can achieve interesting, and sometimes wacky, results. You can also 'de-fish' or correct for the extreme fisheye by using image-editing software, such as Adobe Photoshop, Nikon's Capture NX 2, and DxO Optics. The end result of correcting your image is that you get a reduced field of view. This is akin to using a rectilinear wide-angle lens.

4.12 An image taken with a Nikon 10.5mm fisheye lens. Notice how the lens distorts the horizon line.

Vibration Reduction Lenses

Nikon has an impressive list of lenses that offer Vibration Reduction (VR). This technology is used to combat image blur caused by camera shake, especially when you hand hold the camera at long focal lengths. The VR function works by detecting the motion of the lens and shifting the internal lens elements. This allows you to shoot up to 3 stops slower than you would normally.

If you're an experienced photographer, you probably know this rule of thumb: To get a reasonably sharp photo when handholding the camera, you should use a shutter speed that corresponds to the reciprocal of the lens's focal length. In simpler terms, when shooting at a 200mm zoom setting, your shutter speed should be at least 1/200 second. When shooting with a wider setting, such as 28mm, you can safely hand hold the camera at around 1/30 second. Of course, this is just a guideline; some people are naturally steadier than others and can get sharp shots at slower speeds. With the VR enabled, you should theoretically be able to get a reasonably sharp image at a 200mm setting with a shutter speed of around 1/30 second. I find that this is only possible if you have really steady hands. At wider focal lengths, you have a better chance of getting a four-stop advantage. (You won't be able to hand hold a 1-second exposure no matter how steady you are.)

Although the VR feature is good for providing some extra latitude when you're shooting with low light, it's not made to replace a fast shutter speed. To get a good, sharp photo when shooting action, you need to have a fast shutter speed to freeze the action. No matter how good the VR is, nothing can freeze a moving subject but a fast shutter speed.

Another thing to consider with the VR feature is that the lens's motion sensor may overcompensate when you're panning, causing the image to actually be blurrier. So, in situations where you need to pan with the subject, you may need to switch off the VR. The VR function also slows down the AF a bit, so when catching the action is very important, you may want to keep this in mind. However, Nikon's newest lenses have been updated with VR II, which Nikon claims can differentiate between panning motion and regular side-to-side camera movement.

While VR is a great advancement in lens technology, few things can replace a good exposure and a solid monopod or tripod for a sharp image.

Third-party Lenses

Several companies make lenses that work flawlessly with Nikon cameras. In the past, third-party lenses had a bad reputation of being, at best, cheap knock-offs of the original manufacturer's. This is not the case anymore: A lot of third-party lens manufacturers have started releasing lenses that rival some of the originals (usually at half the price).

Although you can't beat Nikon's professional lenses, there are many excellent third-party lens choices available. The three most prominent third-party lens manufacturers are Sigma, Tokina, and Tamron. Each of these companies makes lenses that cover the entire zoom range.

I have included a number of examples of third-party lenses throughout this chapter. Although I currently have a full line of Nikon pro lenses, I also have a few third-party lenses simply because they are smaller and lighter than Nikon's pro lenses, especially the constant aperture f/2.8 lenses. I highly recommend checking into some third-party lenses if you're looking for a fast constant aperture zoom lens for not a lot of money.