8

What You Need to Know About Music Copyright and Licensing

Before we get into this topic, we need to emphasize that we’re not attorneys. We can only share what we know from our years of experience working with music rights for nonfiction storytelling. This chapter is not legal advice. We strongly recommend you speak to a legal professional regarding your specific production. Okay, now that we’ve provided that important disclaimer, on with the show!

A Brief History of Music Rights in the United States

As a storyteller, you might find it useful to know a bit about the story of music rights in the United States from the perspective of the songwriter. First, you should know that a musical work is considered copyrighted from the very moment music and lyrics have been set down on paper, recorded, or stored on a computer. No registration is necessary to protect ownership. As a songwriter, you can also register your work with the US Copyright Office. It’s a pretty simple matter. Instructions on how to register, which can be done electronically for a small fee, can be found online (see our Resources for the link). This is the same link for registering your script, podcast, script treatment, or screenplay. It’s important for you as a filmmaker to know that the copyright in the composition is distinct from the copyright in the sound recording, also known as the “master.” We’ll get to that in a moment.

In addition to copyright, there is the matter of publication. Performing a work of music doesn’t constitute publishing it. To publish it, you don’t need to go through a professional publishing house. Sharing it through your YouTube or Vimeo channel is considered an act of publication. However, many of the music rights processes which we have today stem from the “old days” of a work being published and distributed to the public on paper. Some of the earliest days of music publishing began in the 19th century, when the industry really began to flourish. A few blocks of New York City’s 28th Street, between 5th Avenue and Broadway, became known as Tin Pan Alley. This area became a creative vortex filled with some of the most prolific music composers and publishers in the history of American song. The name supposedly came from the sound of the cheap, upright pianos these writers used to crank out their music. Songwriters like Stephen Foster (“My Old Kentucky Home,” “Camptown Races,” “Oh! Susanna,” and others) churned out more than 70 songs and lyrics in less than 40 years in the early to mid-1800s. Other musicians soon followed, such as the even more prolific Harry Warren (“Lullaby of Broadway”, “You’ll Never Know,” and “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe”), the child of Italian immigrants whose birth name was Salvatore Antonio Guaragna. Warren composed more than 800 songs, was one of the first composers to write for film, and won three Oscars. Despite being prolific, these composers didn’t make much money. That’s because the publishing industry kept a firm grip on the rights to most of their songs and therefore managed to keep most of the royalties. (One common maneuver was to have one of the publishers’ names added as a co-composer, so that the publishing house could keep more money.) Eventually, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) was formed in 1914 to formalize the process of royalties and payments and to try to give some standardized rights protections to composers as well as publishers.

Why all this back story? Often, content creators treat music as something to use for the soundtrack of a video without considering the fact that another creator invented it and another entity published it. Thus, we now turn to how to accomplish compensating those parties while staying on budget for your project.

Types of Music Rights

When creating your story, you are most likely to think about the need for music. However, you may also need rights for music that you picked up in recording the natural sound of a scene—such as audio playing on a radio in a car where you are filming a scene or the music selected by a dance troupe for their performance that you are filming. You may also wish to license sound effects and Foley sounds. Many filmmakers also use a narrator and will need a talent release to use this voice in the soundtrack. Let’s start with a summary of all of the different kinds of rights that you’ll need to understand in order to create your soundtrack. These can include:

![]() Mechanical License

Mechanical License

![]() Synchronization Rights

Synchronization Rights

![]() Master Recording Rights

Master Recording Rights

![]() Digital Download License

Digital Download License

Additional considerations are:

![]() Performance Rights – live stage and recorded

Performance Rights – live stage and recorded

![]() Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses

Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses

![]() Estate Releases

Estate Releases

![]() Talent Releases

Talent Releases

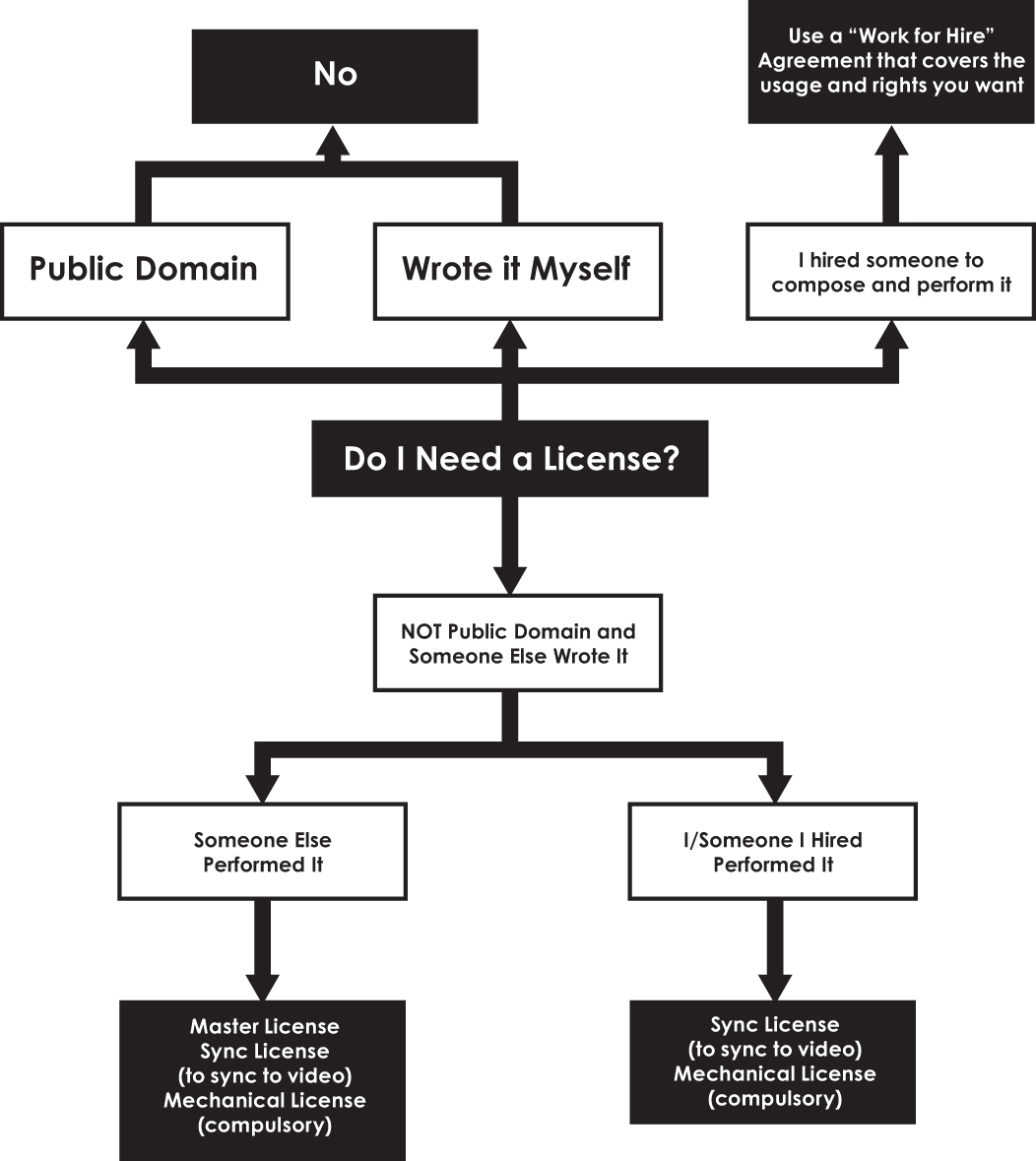

Don’t panic. This stuff isn’t as hard as it looks. Here’s a handy flow chart to help you understand and make these decisions (Figure 8.1).

Cost of Music Licenses

Just as there is a range of artists, so too is there a range of costs for licenses. The least expensive licenses are for stock music, since those tracks can be sold more than once by the company that owns them. I’ve seen rates as low as $50 per track for non-broadcast use and $350 per track for broadcast use. That use can be unlimited, but that means the track is married to that particular video, not to other videos you have created or other versions of the original video. Be forewarned that many cheaper sound libraries don’t provide great mixes. Some of them may sound pretty tinny in your soundtrack. Licensing a well-known song can cost several thousand dollars in fees per year for the various licenses, plus the cost of an agent to handle securing of them. But the impact of a well-known song could make or break your story. So, you will need to research your options at the start. You may want to create a hybrid soundtrack, where you use some custom sounds or music tracks and some stock sounds and songs. Many filmmakers also turn to new and emerging artists who are eager for the visibility of having their name in the credits and featured in film promos. The options and opportunities are wide open, so create a realistic licensing budget, but also get creative with your thinking.

FIGURE 8.1 Follow the flowcharts to help you answer the question “Do I Need a License?”

Fair Use

Before we go further, let’s talk about the “elephant in the room”: fair use. Referenced in Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act (found on the U.S. Copyright Office website), fair use is “a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.” The key concept to remember here is that fair use is an exception to another party’s copyright—it is not a right in and of itself. Because fair use is considered to be a “doctrine” and is guided by case law rather than a specific set of legislative rules, grey areas abound. For example, one of the criteria of the doctrine is “transformative use.” Many filmmakers could argue that simply by being part of a film and not an artist’s recording, an audio work may have been transformed. There are other criteria as well, including how much of the work you use and the impact on the market value of the original work. Almost every nonfiction storyteller will claim fair use at one point or another in their creative careers. And often, it does apply. Just as often, it doesn’t. Fair use is not about whether or not you are charging people to see your film. If you record a Beyoncé song in your living room, the recording and unlicensed performance (not the sale thereof) are the infringing acts. Fair use is not something you can automatically claim because your content was created for or by a nonprofit. It is not automatic because you are only using five seconds of a song. Fair use has traditionally been strongly supported by the courts when applied to uses that are in educational institutions (such as a film class) or when a work is quoted in a journalism or scholarly work. There is also a long tradition of fair use for satirical works. It’s less clear about everything else. Even if you believe you have an ironclad fair use exception, you may be dragged into expensive litigation by the owner of that intellectual property to prove your case in court.

There’s a big conversation going on now in the nonfiction field, primarily among documentary filmmakers and film programs, about which usages could and should be deemed fair use. The discussion centers around the freedom to tackle difficult and important issues for civic discourse without being hampered by the automatic withholding of rights by license-holders. And it’s true that large license-holders tend to say “no” to small filmmakers, mostly because they don’t want to be bothered with the paperwork in exchange for small fees. Another issue I’ve come across more often lately is finding an audio clip of a speech or a sequence that I know is free government footage on a stock footage website and yet the website is charging for it. With clips from government archives, it’s worth hunting them down directly from the federal agency, presidential library, or other collection involved rather than going through the stock aggregators. On these fronts, nonfiction creatives must stake a claim in order to do the important work of storytelling in a free society. To learn more about documentary best practices, and some guidelines on fair use, we refer you to the excellent information on fair use best practices developed by the Center for Media and Social Impact at American University.

One way you could determine if your project meets fair use guidelines is to use the checklist from Cornell University on copyright (see the Resources section of this book). As you will see, there are issues that favor a determination of fair use, and those that do not. Nothing is clear cut. And a few of the items on the checklist are in tension with one another (transforming the work leans towards a yes for fair use, but if the work you want to use is creative—such as a piece of music—then fair use is not favored). Another criteria that disfavors fair use is that there is another “reasonably available licensing mechanism for obtaining permission to use the copyrighted work.” And the fact is, for almost all circumstances these mechanisms do exist. We’ll tackle these in just a moment.

When we are working on our respective projects, Cheryl and I lean towards assuming that a significant percentage of archival and preexisting content does not fall under fair use, and our attorneys agree with us. We also believe that copyright holders (including us) should be compensated for their works appearing in, or being heard in, other works. We have both seen the term fair use thrown around when in reality it is more likely that a producer just doesn’t want to spend the time researching to whom licensing fees are owed or an organization forgot to budget for licensing fees. So, as you begin to collect music cues, sound effects, and archival materials for your production, make sure you work through the rights issues for the material you use. That might lead you to find a few different options for a single sound cue, just in case. We remind you again that we are not providing legal advice. You should always check with an attorney who specializes in intellectual property rights and can review your specific project and usage plan. Bottom line: if you are going to claim fair use, speak to your attorney—and/or the attorney(s) for the organization for whom you are producing the content—in order to make your own risk assessment.

Locating Music Copyright Holder and Publisher

Your first step when wanting to use a previously published piece of music as a component in the score of your film is to locate who owns the copyright and determine who is the publisher. They are not typically the same person or entity. Copyright of the composition is often owned by the artist, but managed by music publishing companies. Sound recording rights are often managed by record labels. The best place to start your search would be a Performing Rights Organization (PRO). The biggest by far is ASCAP (remember, that group founded in 1914 to protect music rights holders), followed by Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), and then SESAC. Each organization represents different copyright holders, including songwriters, composers, and publishers. And each PRO licenses only the copyrighted works of its own respective copyright holders. So, you have to find out which one represents the songwriter, composer, or publisher whose license you need. SESAC-represented music includes quite a bit created for media projects like films, TV shows, and commercials. So, if any such content is contained in your film, you will need to seek out a SESAC license. Links to these PROs are in our Resources section, and you can conduct searches based on song title through their respective websites.

License Definitions to Know as a Content Creator

Compulsory License

Thanks to a provision known as a Compulsory License, our copyright system allows you an automatic granting of a license as long as you pay the license-holder for using their material. This is how bands can get permission to record “covers” of other peoples’ compositions, provided they pay a fee for each song recorded. So as long as a band pays that royalty (or you do, as the filmmaker recording a cover song for your film), the license is automatic.

Mechanical License

Before the aforementioned cover band can release that copyrighted song on a CD, as a digital download, or via a streaming medium, they need not just the Compulsory License but also another license called a Mechanical License. As a filmmaker, you need to know that this Mechanical License does not include your right to put that recording into your film and then make and distribute copies of your film containing the song. For that, you will need a Master Use License, described below.

Master Use License

The master recording refers to the song publication—literally the means by which a song goes out to the public. Typically, this master recording is owned by a record label, though more and more artists are now holding onto their own publishing rights. When you purchase a Master Use License, you are receiving permission to use the master recording in your visual production. If you plan to use the song as part of your soundtrack, you will also need a Synchronization License in order to synchronize the music with the visuals in your film.

Synchronization License

Popularly known as a “Sync” License, this agreement allows you, the licensee, the right to literally synchronize the recording of a particular song or stock music track to the visuals in your film. Sync Licenses can be just a few hundred dollars. Or they can be thousands. In my experience, the fee range depends on a number of variables, such as how popular the song or artist has become, the type of production you are creating—commercial, corporate, documentary, etc.—and how you will be using the material in that work. (See Important Questions to Answer Before You License below.)

Important Questions to Answer Before You License

Once you’ve figured out how to track down the rights-holder(s) of music you want to use in your film, you will need to be sure you have the answers to these questions, which will likely be asked at several steps of the licensing process.

Who is the artist or band who performs the song?

Who is the publisher?

What type of media distribution do you want to use the song for? For example, film festival, cable TV, internet, theatrical, commercial, or “any and all media.” Are there restrictions on physical distribution vs. online distribution? Dollar amount limitations of physical product?

What is the term of use? Try to think as broadly as you can. It will cost more to license for a longer period of time, but it will also cost you in time if you have to go back and track down rights again later, because the usage will be longer.

What are the “territories” of usage? Again, think broadly. If your film is being distributed by your local public TV station in Nebraska, but is likely to be picked up by PBS and distributed more widely, start with “North America” as your minimum territory.

What is the length of the clip being used? Typically, it’s harder to get permission to use an entire song than just a clip.

How is the song being used? In other words, is it the background music for your final titles, or is there a clip of a music video on screen in one of your scenes?

What fees are you prepared to offer? You’d be surprised, most licenses are negotiable. You will need to have a number in mind. Typically, there will be a fee for the master recording license and another fee for the publisher. Remember that there can be more than one publisher.

Avoiding Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Takedowns

A common problem for media makers is having their media temporarily removed from a distribution platform for licensing violations, which is something you want to avoid. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is a US law that protects content creators from having their work shared on the internet without proper licensing. As a content creator, you want this law to exist, because it means that you can protect your content with embedded code and be sure someone else isn’t profiting from it without your permission or profit. One of the common reasons a video gets flagged is that music playing in the background inside a scene has not been properly licensed, even when the score and other elements have been (see below for more details). Since DMCA takedowns are an automated process, your video could be flagged even if you do have all the proper licenses. So, keep digital copies of all your licenses. Generally, I recommend keeping copies not just in your computer files for the project, but also inside the editing project folder where all the footage lives in a folder cleverly labelled “Licenses.” That way, you can provide proof of proper license when required, and any editor working with the footage in the future will know the parameters of the license if they are cutting a new version of the video.

Live Performances in Your Video

One of the tricky areas of music licensing presents itself when you are filming a performance that itself contains music. There is no “one size fits all,” so let’s run through two common scenarios. In our first scenario, you are filming at an awards event. As each awardee comes on stage, several seconds of a popular song is played. Let’s say one person gets Bill Conti’s iconic theme “Gotta Fly Now” from the film Rocky (1976) and another gets the Katy Perry song “Roar.” You are filming these awards to create a film about the organization, and your video will be played on the organization’s YouTube channel after the event. The event organizers will need to pay a license fee for using copyrighted music at their event. Both BMI and ASCAP charge a sliding scale depending on whether or not an entrance fee is charged, whether the music used is played in a live performance with a band versus recorded music, and how many attendees are at your event. The fee is not dependent on whether or not the organization is a charity (for more details, see our resource links on festivals policy for BMI and ASCAP). However, those fees only cover the live moments at your event when those pieces of music are played. They do not give you the sync license to play back this same music in the video recording of your event. So, you will still need a sync license for the content. If you don’t, you may get a DCMA takedown notice.

In our second scenario, you are producing a documentary film about a musician who travels the world giving performances in trauma-filled regions. In one scene, the musician performs a cover song of a piece by a renowned artist. This is a pivotal scene in your film, and you intercut shots of the musician and the faces of the audience, enthralled and transported by her emotional performance. Do you need to get a mechanical and sync license for the song? As I’m not an attorney, I can’t tell you whether or not you would have a strong case that both her performance and your filmic representation have transformed the original work into something new worthy of being deemed fair use. However, if you seek a major distributor for this film, you will likely be asked to back up your claim of fair use, as well as provide all other copies of releases plus a copy of your Errors and Omissions insurance, which is based on your claims. (We’ll cover E&O in a moment.) The bottom line is you need to go into the process with knowledge and a plan.

Licensing Stock Music and Sound Effects

One of the best things about using a stock library, among the many options of sounds and songs, is the fact that the licensing component will be very straight forward. When you select a song you want to use for your production, you will pay for it and receive a license. This license will cover the Master License and Sync License for using the song to picture. You will typically have options for the type of license you are receiving based on distribution. For example, with the license shown in Figure 8.2 you can use this music cut for online video, social media video, a video for a website, a corporate presentation, a slideshow, and videos on YouTube, as well as on a free app or game for Android or iPhone. You would need a different license if you want to use this cut of music in a theatrical release film or a commercial advertisement. As you might expect, the fees are higher for those uses. But I have found that stock houses are open to negotiations, based on your expected distribution, the length of the license, etc.—all of those questions you asked yourself and answered (on pages 134–135) prior to getting started. One thing to remember about working with stock music is that if you are working in an organization that produces many different video projects in a given year, you can save money by purchasing an annual blanket license to use music from that stock house. To maintain your license, you will need to report all of the music cues you have used (usually on a quarterly basis), including the usage type, such as web or live event distribution. This can be a significant cost savings over paying cue by cue for the music and gives you access to a wide range of musical styles and genres (Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2 Excerpt from a standard non-broadcast music license.

Licensing Music from a Composer

Many people think licensing music from a composer is cost-prohibitive. On the contrary, I often find that the amount of time it saves me hunting down six different types of music for the various twists and turns in the story, and then editing and mixing them seamlessly, is well worth it. Plus, many composers will work with you on a Work-for-Hire basis, and let you do a “buy out” of the piece of music for a flat fee. You should be up front about your anticipated distribution. If it is small, or for a non-profit, most composers will work with you on their fee. I have also made arrangements with composers that they not reuse the same theme for a period of time—let’s say two years—but after that they can rework that music bed for another client. That also allows the composer to work with me on price. The best part about working with a composer is getting just the right moments, moods, and, most importantly, transitions in your score. Music majors at local colleges and universities are great sources for Work-for-Hire composition. We’ll delve more into the process in Chapter 9, Music Scores.

Rights of Publicity Applies to Voices

The Right of Publicity is something you and I have if we live in the United States, the European Union, Canada, and several other countries. This right applies to every person in that country, whether a known celebrity or not. The right of publicity means we control the use of our likeness—including our voice—and that someone else can’t commercially benefit from it without our permission. These rights continue to exist even after we are dead (the timeframe can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction). Journalistic works are generally exempt from having to be concerned about the right of publicity of people in their content via a fair use exception, though sometimes this has been challenged in the courts. Here’s where the right of publicity applies to us as filmmakers with respect to sound: don’t use a famous person’s voice—or something that sounds like it—in your production if you are not prepared to get permission. An example would be the case of Tom Waits v. Frito Lay, Inc. I won’t get into the details, but suffice it to say that someone imitating his famous voice in the soundtrack of a commercial was not okay with him, and he sued and won (a link is provided in our Resources section). Bette Midler also brought a case and won. Bottom line, think twice before using a “sound-alike” voiceover artist and asking them to imitate a famous voice.

Talent Releases

A talent release is an agreement that gives you as the content creator the proper permission to distribute your film that includes the voice, image and/or performance of “talent.” Generally, you will use such a form for unpaid on-camera interviews as well as paid actors. When you use a voiceover talent, you should also get a release. If you are using union talent, the release will already be a part of the signatory agreement. If you are not a union signatory—and many independent producers are not—then you can use a signatory agency to book and pay your union voiceover talent. They can help you with any questions about releases. If you are using non-union talent, or need a release for someone you are interviewing, I think it’s worth the time to have an attorney craft at least your first one. Then you can create derivative versions for other projects. The internet is filled with standard talent releases, which are great to look at for a guide, but you want to be sure you are covered for the specific use you want for your production. Be careful if you go this route—the road to perdition is paved with producers who used forms they “found” online. You want to be sure you have the ability to make edits to the voice, or even alter it (which might mean EQ-ing the voice during your mix). You want the maximum flexibility as a creative, and you also don’t want to have to hunt down all the people involved in your film several years after the fact, when suddenly you win that much-hoped-for distribution.

Using an Agent or Handling Rights Yourself

Clearing rights yourself isn’t as complex as it may seem. But the decision of whether or not to handle it yourself is not always a matter of saving money. For example, many times I will choose to work with an agent because I know they have worked with a particular artist before, or a song that is getting a lot of requests for use in videos. If I know that they have a relationship with the artist and publisher involved, then I know they might have a better shot than I do at getting the license and will save me or my client significant amounts of time and money. Agents who can handle licensing for you—and many if not most are not attorneys—will charge you an initial fee for the negotiation, and then another fee for securing the licenses if you decide to move forward. I have paid fees as low as $700 for the initial negotiation work. It really depends on what you are asking, how hard they feel it will be to do the negotiation, and whether they already have relationships with those agents and publishers.

I have also cleared rights myself and would not discourage you from doing so, too. Because my films are primarily for nonprofit organizations and causes, I will often go to the artist directly to gauge their willingness to have their song used in our soundtrack. Having the artist say “yes” goes a long way when negotiating with the publisher. In many cases, having this support can keep you from having the door shut in your face, figuratively speaking, by one of the large rights-holding entities. And in fairness to them, their attorneys and licensing folks are probably paid quite a bit of money, so it’s hard for them to justify small negotiations for nonfiction shorts and documentaries with limited release. One thing I’ve found is that an artist’s interest can also help clear the rights for less than the standard rate. I was able to clear use of the Men Without Hats song “Safety Dance” for an educational safety video by first contacting the original artist and then getting his referral to their agent. I was similarly able to clear a version of Bobby Picket’s famous “The Monster Mash,” for which we wrote new lyrics with the hope that we could use them in an animated sequence for a children’s educational program. I reached out to Pickett himself, through an intermediary who knew his agent, and he was so taken with our idea that he offered to record our version (and did). Because we were recording our own new version of the song, we paid an attorney to negotiate a sync license and a mechanical license for the original song. By the way, if you decide to produce a cover song, you can handle the license through CD Baby’s handy service (see our Resources collection). But you will still need to get the sync license for using it in a video, which they do not offer at this time since their focus is albums. The bottom line is this: artists understand other artists, and are often willing to lend their support for good causes. I believe the key is twofold: (1) offer them some remuneration, which they are entitled to receive for their copyrighted works. This shows your respect for the work and the artist. And (2) make sure the usage is consistent with the person and brand of the artist. They are more likely to say yes if you are pitching a cause or content that is relevant and would reflect well on them.

Errors and Omissions Insurance

When you have licensed or fair use elements in your production—images or audio—and want to get public distribution for your film, that’s when Errors and Omissions Insurance (E&O) comes into play. Most networks and major distributors will require that you have it in order for your film to get a distribution deal. E&O insurance is essentially malpractice insurance for filmmakers. Unfortunately, you as the content creator are expected to cover the cost, which can be several thousand dollars. Keep all those licenses and talent releases we’ve talked about handy, because you will need them when making your application. From these documents, you will need to create a detailed film log so that the insurer understands where you have secured right, and where you may be relying on fair use exceptions. For her documentary The Art of Dungeons & Dragons, co-Director/co-Producer Kelley Slagle explains this detailed process was one of the hardest things she had to do in the years-long process of making the film.

“We had to create an exhaustive film log, where for every cut in the film we were required to note the timecode, detail what was in the shot and audio track, confirm we had all releases, licenses, and contracts for who and what was on the screen, and whether we relied on any fair use exceptions. There were also trademark and copyright searches done by an attorney, and a fair use opinion letter from our attorney expressing his opinion that any unlicensed IP fit under a fair use exception. It took us nearly 60 hours between three producers to get everything together for the [insurance] broker, and another couple of hours to complete the application process.”

Who Can Help Me License?

An intellectual property attorney who specializes in film productions can be quite helpful as you navigate licensing. You may believe that legal fees will be too expensive for your budget, but after-the-fact problems and reedits to cut out problematic material would be much more expensive. There are also a rising number of solo and small practice attorneys willing to work for reduced or flat fees with documentary filmmakers if they can verify the scope of the project up front. If you don’t want to use an attorney, you can use a music clearing agent. These folks are experienced negotiators and often have worked with major artists and commonly licensed songs, so they have a good sense of what rates can be negotiated. Some examples of clearing agents are included in our Resources section. There are also companies that pitch themselves as “audio agencies.” These include companies like Jungle Punks who can help you create an original score or license one that you need. Or you could try a hybrid like Rumble Fish that both manages rights for music creators and helps distributors and filmmakers get tracks and licenses, often from indie artists who want exposure. And of course, you can do the work yourself. But we’d still recommend running everything past an attorney if your film is going into wide release.

Final Tips on Music Licensing Budgets

Sound is integral to all nonfiction stories. The music tracks and sound effects are often some of the first things I plan for, not a last-minute component added in at the end. This also helps with budgeting. Some strategies I use to keep my budgets as low as possible are: (1) do flat buyouts with composers, (2) negotiate a license renewal that is the same as the initial license for the next year or two (rather than an automatic increase), (3) reach out to artists directly if you are planning nonprofit use; while they do not generally manage their own rights, their support may help you get a better rate from the publisher, and (4) do your own initial legwork to save on legal fees; find out who owns the copyright and who owns the publishing rights, and be clear about how you will be using the piece of music.

Tips on Music Licensing

![]() Consider who owns the rights to a piece of music before you fall in love with it in your soundtrack.

Consider who owns the rights to a piece of music before you fall in love with it in your soundtrack.

![]() If you want to license a cut from a popular band or composer, determine up front if you are willing to cover the budget for the right licenses. If you have a small budget, be sure you are willing to put in the time and effort to try to negotiate a lower than standard fee, and understand you may not succeed.

If you want to license a cut from a popular band or composer, determine up front if you are willing to cover the budget for the right licenses. If you have a small budget, be sure you are willing to put in the time and effort to try to negotiate a lower than standard fee, and understand you may not succeed.

![]() You can definitely negotiate licenses on your own, but in many cases it is best—and more efficient—to hire an experienced licensing agent and/or intellectual property attorney to assist you with this process.

You can definitely negotiate licenses on your own, but in many cases it is best—and more efficient—to hire an experienced licensing agent and/or intellectual property attorney to assist you with this process.

![]() Not everything falls under fair use. Become knowledgeable about the parameters of claiming fair use, and be prepared to offer an attorney opinion letter outlining the basis of your claim

Not everything falls under fair use. Become knowledgeable about the parameters of claiming fair use, and be prepared to offer an attorney opinion letter outlining the basis of your claim

![]() For most documentary distribution, and some other types of nonfiction productions where you are conveying factual information about areas such as medical procedures or pharmaceuticals, your production will need to be covered under E&O insurance. Be sure you know the process and keep track of all of your licenses.

For most documentary distribution, and some other types of nonfiction productions where you are conveying factual information about areas such as medical procedures or pharmaceuticals, your production will need to be covered under E&O insurance. Be sure you know the process and keep track of all of your licenses.

![]() If you license music on a regular basis, for a company or nonprofit that produces many videos a year, consider buying a blanket license from a stock music library rather than paying for each cue.

If you license music on a regular basis, for a company or nonprofit that produces many videos a year, consider buying a blanket license from a stock music library rather than paying for each cue.