Chapter 1 What Is a Project?

Congratulations on your decision to study for and take the Project Management Institute (PMI®) Project Management Professional (PMP®) certification exam (PMP® exam). This book was written with you in mind. The focus and content of this book revolve heavily around the information contained in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Fifth Edition, published by PMI®. I will refer to this guide throughout this book and elaborate on those areas that appear on the test. Keep in mind that the test covers all the project management processes, so don’t skip anything in your study time.

When possible, I’ll pass on hints and study tips that I collected while studying for the exam. My first tip is to familiarize yourself with the terminology used in the PMBOK® Guide. Volunteers from differing industries from around the globe worked together to come up with the standards and terms used in the guide. These folks worked hard to develop and define project management terms, and the terms are used interchangeably among industries. For example, resource planning means the same thing to someone working in construction, information technology, or healthcare. You’ll find many of the PMBOK® Guide terms explained throughout this book. Even if you are an experienced project manager, you might find you use specific terms for processes or actions you regularly perform but the PMBOK® Guide calls them by another name. So, the first step is to get familiar with the terminology.

The next step is to become familiar with the processes as defined in the PMBOK® Guide. The process names are unique to PMI®, but the general principles and guidelines underlying the processes are used for most projects across industry areas.

This chapter lays the foundation for building and managing your project. I’ll address project and project management definitions as well as organizational structures. Good luck!

Is It a Project?

Let’s start with an example of how projects come about, and later we’ll look at a definition of a project. Consider the following scenario: You work for a wireless phone provider, and the VP of marketing approaches you with a fabulous idea—“fabulous” because he’s the big boss and because he thought it up. He wants to set up kiosks in local grocery and big-box stores as mini-offices. These offices will offer customers the ability to sign up for new wireless phone services, make their wireless phone bill payments, and purchase equipment and accessories. He believes that the exposure in grocery stores will increase awareness of the company’s offerings. After all, everyone has to eat, right? He told you that the board of directors has already cleared the project, and he’ll dedicate as many resources to this as he can. He wants the new kiosks in place in 12 stores by the end of this year. The best news is he has assigned you to head up this project.

Your first question should be “Is it a project?” This might seem elementary, but projects are often confused with ongoing operations. Projects are temporary in nature; have definite start and end dates; produce a unique product, service, or result; and are completed when their goals and objectives have been met and signed off by the stakeholders or when the project is terminated.

When considering whether you have a project on your hands, you need to keep some issues in mind. First, is it a project or an ongoing operation? Next, if it is a project, who are the stakeholders? And third, what characteristics distinguish this endeavor as a project? We’ll look at each of these next.

Projects vs. Operations

Projects are temporary in nature and have definitive start dates and definitive end dates. The project is completed when its goals and objectives are accomplished to the satisfaction of the stakeholders. Sometimes projects end when it’s determined that the goals and objectives cannot be accomplished or when the product, service, or result of the project is no longer needed and the project is canceled. Projects exist to bring about a product, service, or result that didn’t exist before. This might include tangible products, components of other products, services such as consulting or project management, and business functions that support the organization. Projects might also produce a result or an outcome, such as a document that details the findings of a research study. In this sense, a project is unique. However, don’t get confused by the term unique. For example, Ford Motor Company is in the business of designing and assembling cars. Each model that Ford designs and produces can be considered a project. The models differ from each other in their features and are marketed to people with various needs. An SUV serves a different purpose and clientele than a luxury sedan or a hybrid. The initial design and marketing of these three models are unique projects. However, the actual assembly of the cars is considered an operation—a repetitive process that is followed for most makes and models.

Determining the characteristics and features of the different car models is carried out through what the PMBOK® Guide terms progressive elaboration. This means the characteristics of the product, service, or result of the project are determined incrementally and are continually refined and worked out in detail as the project progresses. More information and better estimates become available the further you progress in the project. Progressive elaboration improves the project team’s ability to manage greater levels of detail and allows for the inevitable change that occurs throughout a project’s life cycle. This concept goes along with the temporary and unique aspects of a project because when you first start the project, you don’t know all the minute details of the end product. Product characteristics typically start out broad-based at the beginning of the project and are progressively elaborated into more and more detail over time until they are complete and finalized.

Operations are ongoing and repetitive. They involve work that is continuous without an ending date, and you often repeat the same processes and produce the same results. One way to think of operations is the transforming of resources (steel and fiberglass, for example) into outputs (cars). The purpose of operations is to keep the organization functioning, whereas the purpose of a project is to meet its goals and to conclude. At the completion of a project, or at various points throughout the project, the deliverables may get turned over to the organization’s operational areas for ongoing care and maintenance. For example, let’s say your company implements a new human resources software package that tracks employees’ time, expense reports, benefits, and so on, like the example described in the sidebar “The New Website Project.” Defining the requirements and implementing the software is a project. The ongoing maintenance of the site, updating content, and so on are ongoing operations.

It’s a good idea to include some members of the operational area on the project team when certain deliverables or the end product of the project will be incorporated into their future work processes. They can assist the project team in defining requirements, developing scope, creating estimates, and so on, helping to assure that the project will meet their needs. The process of knowledge transfer to the team is much simpler when they are involved throughout the project; they gain knowledge as they go and the formal handoff is more efficient. This isn’t a bad strategy in helping to gain buy-ins from the end users of the product or service either. Often, business units are resistant to new systems or services, but getting them involved early in the project rather than simply throwing the end product over the fence when it’s completed may help gain their acceptance.

Managing projects and managing operations require different skill sets. Operations management involves managing the business operations that support the goods and services the organization is producing. Operations managers may include line supervisors in manufacturing, retail sales managers, and customer service call center managers. The skills needed to manage a project include general management skills, interpersonal skills, planning and organization skills, and more. The remainder of this book will discuss project management skills in detail.

According to the PMBOK® Guide, several examples exist where projects can extend into operations up until and including the end of the product life cycle:

Concluding the end of each phase of the project

Developing new products or services

Upgrading and/or expanding products or services

Improving the product development processes

Improving operations

The preceding list isn’t all inclusive. Whenever you find yourself working on a project that ultimately impacts your organization’s business processes, I recommend you get people from the business units to participate on the project.

Stakeholders

A project is successful when it achieves its objectives and meets the expectations of the stakeholders. Stakeholders are those folks (or organizations) with a vested interest in your project. They may be active or passive as far as participation on the project goes, but the one thing they all have in common is that each of them has something to either gain or lose as a result of the project. Stakeholder identification is not a onetime process. You should continue to ask fellow team members and stakeholders if there are other stakeholders who should be a part of the project.

NOTE

Key stakeholders can make or break the success of a project. Even if all the deliverables are met and the objectives are satisfied, if your key stakeholders aren’t happy, nobody is happy.

The project sponsor, generally an executive in the organization with the authority to assign resources and enforce decisions regarding the project, is a stakeholder. The project sponsor generally serves as the tie-breaking decision maker and is one of the people on your escalation path. The project sponsor is also the person who approves the project charter and gives the project manager the authority to commence with the project. We will cover this topic in more detail in Chapter 2, “Creating the Project Charter.” The customer is a stakeholder, as are contractors and suppliers. The project manager, the project team members, and the managers from other departments, including the operations areas, are stakeholders as well. It’s important to identify all the stakeholders in your project up front. Leaving out an important stakeholder or their department’s function and not discovering the error until well into the project can be a project killer.

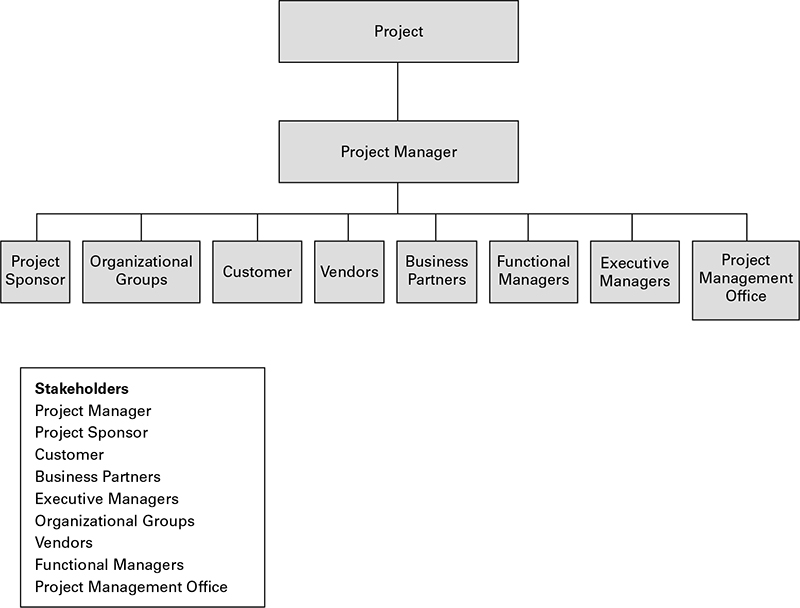

Figure 1.1 shows a sample listing of the kinds of stakeholders involved in a typical project. The org chart view shows a hierarchical view, not an organizational reporting view, of how the stakeholders listed in the chart and in the box below the chart interact with the project manager.

FIGURE 1.1 Project stakeholders

Many times, stakeholders have conflicting interests. It’s the project manager’s responsibility to understand these conflicts and try to resolve them. It’s also the project manager’s responsibility to manage stakeholder expectations. Be certain to identify and meet with all key stakeholders early in the project to understand their expectations, needs, and constraints. When in doubt, you should always resolve stakeholder conflicts in favor of the customer.

Project Characteristics

You’ve just learned that a project has several characteristics:

Projects are unique.

Projects are temporary in nature and have a definite beginning and ending date.

Projects are completed when the project goals are achieved or it’s determined the project is no longer viable.

A successful project is one that meets the expectations of your stakeholders.

Using these criteria, let’s examine the assignment from the VP of marketing (to set up kiosks in local grocery and big-box stores as mini-offices) to determine whether it is a project:

Is it unique? Yes, because the kiosks don’t exist now in the local grocery stores. This is a new way of offering the company’s services to its customer base. Although the service the company is offering isn’t new, the way it is presenting its services is.

Does the project have a limited time frame? Yes, the start date of this project is today, and the end date is the end of this year. It is a temporary endeavor.

Is there a way to determine when the project is completed? Yes, the kiosks will be installed, and services will be offered from them. Once all the kiosks are intact and operating, the project will come to a close.

Is there a way to determine stakeholder satisfaction? Yes, the expectations of the stakeholders will be documented in the form of deliverables and requirements during the Planning processes. Some of the requirements the VP noted are that customers can sign up for new services, pay their bills, and purchase equipment and accessories. These deliverables and requirements will be compared to the finished product to determine whether it meets the expectations of the stakeholders.

Houston, we have a project.

What Is Project Management?

You’ve determined that you indeed have a project. What now? The notes you scratched on the back of a napkin during your coffee break might get you started, but that’s not exactly good project management practice.

We have all witnessed this scenario: An assignment is made, and the project team members jump directly into the project, busying themselves with building the product, service, or result requested. Often, careful thought is not given to the project-planning process. I’m sure you’ve heard co-workers toss around statements like, “That would be a waste of valuable time” or “Why plan when you can just start building?” Project progress in this circumstance is rarely measured against the customer requirements. In the end, the delivered product, service, or result doesn’t meet the expectations of the customer. This is a frustrating experience for all those involved. Unfortunately, many projects follow this poorly constructed path.

Project management brings together a set of tools and techniques—performed by people—to describe, organize, and monitor the work of project activities. Project managers are the people responsible for managing the project processes and applying the tools and techniques used to carry out the project activities. All projects are composed of processes, even if they employ a haphazard approach. There are many advantages to organizing projects and teams around the project management processes endorsed by PMI®. We’ll be examining those processes and their advantages in depth throughout the remainder of this book.

According to the PMBOK® Guide, project management involves applying knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques during the course of the project to meet requirements. It is the responsibility of the project manager to ensure that project management techniques are applied and followed.

Project management is a collection of processes that includes initiating a new project, planning, putting the project management plan into action, and measuring progress and performance. It involves identifying the project requirements, establishing project objectives, balancing constraints, and taking the needs and expectations of the key stakeholders into consideration. Planning is one of the most important functions you’ll perform during the course of a project. It sets the standard for the remainder of the project’s life and is used to track future project performance. Before we begin the Planning process, let’s look at some of the ways the work of project management is organized.

Programs

According to the PMBOK® Guide, programs are groups of related projects, subprograms, or other works that are managed using similar techniques in a coordinated fashion. When projects are managed collectively as programs, it’s possible to capitalize on benefits that wouldn’t be achievable if the projects were managed separately. This would be the case where a very large program exists with many subprojects under it—for example, building an urban live-work-shopping development. Many subprojects exist underneath this program, such as design and placement of living and shopping areas, architectural drawings, theme and design, construction, marketing, facilities management, and so on. Each of the subprojects is a project unto itself. Each subproject has its own project manager, who reports to a project manager with responsibility over several of the areas, who in turn reports to the head project manager who is responsible for the entire program. All the projects are related and are managed together so that collective benefits are realized and controls are implemented and managed in a coordinated fashion. Sometimes programs involve aspects of ongoing operations as well. After the shopping areas in our example are built, the management of the buildings and common areas becomes an ongoing operation. The management of this collection of projects—determining their interdependencies, managing among their constraints, and resolving issues among them—is called program management. Program management also involves centrally managing and coordinating groups of related projects to meet the objectives of the program.

Portfolios

Portfolios are collections of programs, subportfolios, operations, and projects that support strategic business goals or objectives. Let’s say our company is in the construction business. Our organization has several business units: retail, single-family residential, and multifamily residential. Collectively, the projects within all of these business units make up the portfolio. The program I talked about in the preceding section (the collection of projects associated with building the new live-work-shopping urban area) is a program within our portfolio. Other programs and projects could be within this portfolio as well. Programs and projects within a portfolio are not necessarily related to one another in a direct way. However, the overall objective of any program or project in this portfolio is to meet the strategic objectives of the portfolio, which in turn should meet the strategic objectives of the department and ultimately the business unit or corporation.

Portfolio management encompasses centrally managing the collections of programs, projects, other work, and sometimes other portfolios. It also entails facilitating effective management of all the work to meet the organization’s strategic goals. The project management office (discussed in the next section) is typically responsible for managing portfolios. This gives a central, enterprise view to the projects for the organization as a whole and leads to more effective management of the programs and projects within the portfolio. Maximizing the portfolio is critical to increasing success. This includes weighing the value of each project, or potential project, against the business’s strategic objectives, selecting the right programs and projects, eliminating projects that don’t add value, and assuring that resources are available to support the work. It also concerns monitoring active projects for adherence to objectives, balancing the portfolio among the other investments of the organization, and assuring the efficient use of resources. Portfolio managers also monitor the organizational planning activities of the organization to help prioritize projects according to fund availability, risk, the strategic mission, and more. Portfolio management is generally performed by a senior manager who has significant experience in both project and program management.

Table 1.1 compares the differences between projects, programs, and portfolios according to the PMBOK® Guide.

TABLE 1.1 Projects, programs, and portfolios

|

Purpose |

Area of Focus |

Project |

Applies and uses project management processes, knowledge, and skills |

Delivery of products, services, or results |

Program |

Collections of related projects, subprojects, or work managed in a coordinated fashion |

Project interdependencies |

Portfolio |

Aligns projects/programs/portfolios/subportfolios/operations to the organization’s strategic business objectives |

Optimizing efficiencies, objectives, costs, resources, risks, and schedules |

Project Management Offices

The project management office (PMO) is usually a centralized organizational unit that oversees the management of projects and programs throughout the organization. The most common reason a company starts a project management office is to establish and maintain procedures and standards for project management methodologies and to manage resources assigned to the projects in the PMO. PMOs are often tasked with establishing an organizational project management (OPM) framework. OPM helps assure that projects, programs, and portfolios are managed consistently and that they support the overall goals of the organization. OPM is used in conjunction with other organizational practices, such as human resources, technology, and culture, to improve performance and maintain a competitive edge.

According to the PMBOK® Guide, the key purpose of a PMO is to provide support for project managers. This may include the following types of support:

Providing an established project management methodology, including templates, forms, and standards

Mentoring, coaching, and training project managers

Facilitating communication within and across projects

Managing resources

Not all PMOs are the same. Some PMOs may have a great deal of authority and control, whereas others may only serve a supporting role. According to the PMBOK® Guide, there are three types of PMOs: supportive, controlling, and directive. Table 1.2 describes each type of PMO, their roles, and their levels of control.

TABLE 1.2 PMO organizational types

PMO Type |

Role |

Level of Control |

Supportive |

Consulting: |

Low |

Controlling |

Compliance: |

Moderate |

Directive |

Controlling: |

High |

NOTE

A PMO can exist in all organizational structures—functional, projectized, or matrix. (These structures will be discussed later in this chapter.) It might have full authority to manage projects, including the authority to cancel projects, or it might serve only in an advisory role. PMOs might also be called project offices or program management offices or Centers of Excellence.

The PMO usually has responsibility for maintaining and archiving project documentation for future reference. This office compares project goals with project progress and gives feedback to the project teams and management. It assures that projects are aligned with the strategic objectives of the organization, and it measures the performance of active projects and suggests corrective actions. The PMO evaluates completed projects for their adherence to the project management plan and asks questions like “Did the project meet the time frames established?” and “Did it stay within budget?” and “Was the quality acceptable?”

NOTE

Project managers are typically responsible for meeting the objectives of the project they are managing, controlling the resources within the project, and managing the individual project constraints. The PMO is responsible for managing the objectives of a collective set of projects, managing resources across the projects, and managing the interdependencies of all the projects within the PMO’s authority.

Project management offices are common in organizations today, if for no other reason than to serve as a collection point for project documentation. Some PMOs are fairly sophisticated and prescribe the standards and methodologies to be used in all project phases across the enterprise. Still others provide all these functions and also offer project management consulting services. However, the establishment of a PMO is not required in order for you to apply good project management practices to your next project.

Skills Every Good Project Manager Needs

Many times, organizations will knight their technical experts as project managers. The skill and expertise that made them stars in their technical fields are mistakenly thought to translate into project management skills. This is not necessarily so.

Project managers are generalists with many skills in their repertoires. They are also problem solvers who wear many hats. Project managers might indeed possess technical skills, but technical skills are not a prerequisite for sound project management skills. Your project team should include a few technical experts, and these are the people on whom the project manager will rely for technical details. Understanding and applying good project management techniques, along with a solid understanding of general management and interpersonal skills, are career builders for all aspiring project managers.

Project managers have been likened to small-business owners. They need to know a little bit about every aspect of management. General management skills include every area of management, from accounting to strategic planning, supervision, personnel administration, and more. Interpersonal skills are often called soft skills and include, among others, communications, leadership, and decision making. General management and interpersonal skills are called into play on every project. But some projects require specific skills in certain application areas. Application areas consist of categories of projects that have common elements. These elements, or application areas, can be defined several ways: by industry group (automotive, pharmaceutical), by department (accounting, marketing), and by technical (software development, engineering) or management (procurement, research and development) specialties. These application areas are usually concerned with disciplines; regulations; and the specific needs of the project, the customer, or the industry. For example, most governments have specific procurement rules that apply to their projects but wouldn’t be applicable in the construction industry. The pharmaceutical industry is acutely interested in regulations set forth by the Food and Drug Administration. The automotive industry has little or no concern for either of these types of regulations. Having experience in the application area you’re working in will give you a leg up when it comes to project management. Although you can call in the experts who have application area knowledge, it doesn’t hurt for you to understand the specific aspects of the application areas of your project.

The interpersonal skills listed in the following sections are the foundation of good project management practices. Your mastery of them (or lack thereof) will likely affect project outcomes. The various skills of a project manager can be broken out in a more or less declining scale of importance. We’ll look at an overview of these skills now, and I’ll discuss each in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Communication Skills

One of the single most important characteristics of a first-rate project manager is excellent communication skills. Written and oral communications are the backbone of all successful projects. Many forms of communication will exist during the life of your project. As the creator or manager of most of the project communication (project documents, meeting updates, status reports, and so on), it’s your job to ensure that the information is explicit, clear, and complete so that your audience will have no trouble understanding what has been communicated. Once the information has been distributed, it is the responsibility of the people receiving the information to make sure they understand it.

NOTE

Many forms of communication and communication styles exist. I’ll discuss them more in depth in Chapter 8, “Developing the Project Team.”

Organizational and Planning Skills

Organizational and planning skills are closely related and probably the most important skills, after communication skills, a project manager can possess. Organization takes on many forms. As project manager, you’ll have project documentation, requirements information, memos, project reports, personnel records, vendor quotes, contracts, and much more to track and be able to locate at a moment’s notice. You will also have to organize meetings, put together teams, and perhaps manage and organize media-release schedules, depending on your project.

Time management skills are closely related to organizational skills. It’s difficult to stay organized without an understanding of how you’re managing your time. I recommend you attend a time management class if you’ve never been to one. They have some great tips and techniques to help you prioritize problems and interruptions, prioritize your day, and manage your time.

I discuss planning extensively throughout the course of this book. There isn’t any aspect of project management that doesn’t first involve planning. Planning skills go hand in hand with organizational skills. Combining these two with excellent communication skills is almost a sure guarantee of your success in the project management field.

Conflict Management Skills

Show me a project, and I’ll show you problems. All projects have some problems, as does, in fact, much of everyday life. Isn’t that what they say builds character? But I digress.

Conflict management involves solving problems. Problem solving is really a twofold process. First, you must define the problem by separating the causes from the symptoms. Often when defining problems, you end up just describing the symptoms instead of getting to the heart of what’s causing the problem. To avoid that, ask yourself questions like, “Is it an internal or external problem? Is it a technical problem? Are there interpersonal problems between team members? Is it managerial? What are the potential impacts or consequences?” These kinds of questions will help you get to the cause of the problem.

Next, after you have defined the problem, you have some decisions to make. It will take a little time to examine and analyze the problem, the situation causing it, and the alternatives available. After this analysis, the project manager will determine the best course of action to take and implement the decision. The timing of the decision is often as important as the decision itself. If you make a good decision but implement it too late, it might turn into a bad decision.

Negotiation and Influencing Skills

Effective problem solving requires negotiation and influencing skills. We all utilize negotiation skills in one form or another every day. For example, on a nightly basis I am asked, “Honey, what do you want for dinner?” Then the negotiations begin, and the fried chicken versus swordfish discussion commences. Simply put, negotiating is working with others to come to an agreement.

Negotiation on projects is necessary in almost every area of the project, from scope definition to budgets, contracts, resource assignments, and more. This might involve negotiation one on one or with teams of people, and it can occur many times throughout the project.

Influencing is convincing the other party that swordfish is a better choice than fried chicken, even if fried chicken is what they want. It’s also the ability to get things done through others. Influencing requires an understanding of the formal and informal structure of all the organizations involved in the project.

Power and politics are techniques used to influence people to perform. Power is the ability to get people to do things they wouldn’t do otherwise. It’s also the ability to change minds and the course of events and to influence outcomes.

NOTE

I’ll discuss power further in Chapter 8.

Politics involve getting groups of people with different interests to cooperate creatively even in the midst of conflict and disorder.

These skills will be utilized in all areas of project management. Start practicing now because, guaranteed, you’ll need these skills on your next project.

Leadership Skills

Leaders and managers are not the same. Leaders impart vision, gain consensus for strategic goals, establish direction, and inspire and motivate others. Managers focus on results and are concerned with getting the job done according to the requirements. Even though leaders and managers are not the same, project managers must exhibit the characteristics of both during different times on the project. Understanding when to switch from leadership to management and then back again is a finely tuned and necessary talent.

Team-Building and Motivating Skills

Project managers will rely heavily on team-building and motivational skills. Teams are often formed with people from different parts of the organization. These people might or might not have worked together before, so some component of team-building groundwork might involve the project manager. The project manager will set the tone for the project team and will help the members work through the various stages of team development to become fully functional. Motivating the team, especially during long projects or when experiencing a lot of bumps along the way, is another important role the project manager fulfills during the course of the project.

An interesting caveat to the team-building role is that project managers many times are responsible for motivating team members who are not their direct reports. This has its own set of challenges and dilemmas. One way to help this situation is to ask the functional manager to allow you to participate in your project team members’ performance reviews. Use the negotiation and influencing skills I talked about earlier to make sure you’re part of this process.

Role of a Project Manager

Project managers are responsible for assuring that the objectives of the project are met. Projects create value, which in turn increases the business value of the organization. Business value is the total value of all the assets of the organization, including both tangible and intangible elements. The project manager must be familiar with the organization’s strategic plan in order to marry those strategic objectives with the projects in the portfolio. This requires all of the skills we covered in the preceding sections. However, according to the PMBOK® Guide, applying the skills and techniques of project management to your next project is not enough—you must also have the following capabilities:

Knowledge (of project management techniques)

Performance (the ability to perform as a project manager by applying your knowledge)

Personal (behavioral characteristics including leadership abilities, attitudes, and ethics)

Now that you’ve been properly introduced to some of the skills you need in your tool kit, you’ll know to be prepared to communicate, solve problems, lead, and negotiate your way through your next project.

Understanding Organizational Structures

Just as projects are unique, so are the organizations in which they’re carried out. Organizations have their own styles, cultures, and ways of communicating that influence how project work is performed and their ability to achieve project success. One of the keys to determining the type of organization you work in is measuring how much authority senior management is willing to delegate to project managers. Although uniqueness abounds in business cultures, all organizations are structured in one of three ways: functional, projectized, or matrix. It’s helpful to know and understand the organizational structure and the culture of the entity in which you’re working. Companies with aggressive cultures that are comfortable in a leading-edge position within their industries are highly likely to take on risky projects. Project managers who are willing to suggest new ideas and projects that have never been undertaken before are likely to receive a warm reception in this kind of environment. Conversely, organizational cultures that are risk-averse and prefer the follow-the-leader position within their industries are highly unlikely to take on risky endeavors. Project managers with risk-seeking, aggressive styles are likely to receive a cool reception in a culture like this.

The level of authority the project manager enjoys is denoted by the organizational structure and by the interactions of the project manager with various levels of management. For example, a project manager within a functional organization has little to no formal authority. Their title might not be project manager; instead, they might be called a project leader, a project coordinator, or perhaps a project expeditor. And a project manager who primarily works with operations-level managers will likely have less authority than one who works with middle- or strategic-level managers.

We’ll now take a look at each of these types of organizations individually to better understand how the project management role works in each one.

Functional Organizations

One common type of organization is the functional organization. Chances are you have worked in this type of organization. This is probably the oldest style of organization and is, therefore, known as the traditional approach to organizing businesses.

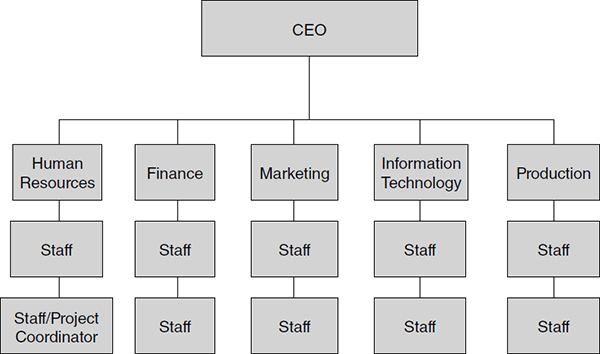

Functional organizations are centered on specialties and grouped by function, which is why they’re called functional organizations. As an example, the organization might have a human resources department, finance department, marketing department, and so on. The work in these departments is specialized and requires people who have the skill sets and experience in these specialized functions to perform specific duties for the department. Figure 1.2 shows a typical organizational chart for a functional organization.

You can see that this type of organization is set up to be a hierarchy. Staff personnel report to managers who report to vice presidents who report to the CEO. In other words, each employee reports to only one manager; ultimately, one person at the top is in charge. Many companies today, as well as governmental agencies, are structured in a hierarchical fashion. In organizations like this, be aware of the chain of command. A strict chain of command might exist, and the corporate culture might dictate that you follow it. Roughly translated: Don’t talk to the big boss without first talking to your boss who talks to their boss who talks to the big boss. Wise project managers should determine whether there is a chain of command, how strictly it’s enforced, and how the chain is linked before venturing outside it.

Each department or group in a functional organization is managed independently and has a limited span of control. Marketing doesn’t run the finance department or its projects, for example. The marketing department is concerned with its own functions and projects. If it were necessary for the marketing department to get input from the finance department on a project, the marketing team members would follow the chain of command. A marketing manager would speak to a manager in finance to get the needed information and then pass it back down to the project team.

FIGURE 1.2 Functional organizational chart

Human Resources in a Functional Organization

Commonalities exist among the personnel assigned to the various departments in a functional organization. In theory, people with similar skills and experiences are easier to manage as a group. Instead of scattering them throughout the organization, it is more efficient to keep them functioning together. Work assignments are easily distributed to those who are best suited for the task when everyone with the same skill works together. Usually, the supervisors and managers of these workers are experienced in the area they supervise and are able to recommend training and career enrichment activities for their employees.

NOTE

Workers in functional organizations specialize in an area of expertise—finance or personnel administration, for instance—and then become very good at their specialty.

People in a functional organization can see a clear upward career path. An assistant budget analyst might be promoted to a budget analyst and then eventually to a department manager over many budget analysts.

The Downside of Functional Organizations

Functional organizations have their disadvantages. If this is the kind of organization you work in, you probably have experienced some of them.

One of the greatest disadvantages for the project manager is that they have little to no formal authority. This does not mean project managers in functional organizations are doomed to failure. Many projects are undertaken and successfully completed within this type of organization. Good communication and interpersonal and influencing skills on the part of the project manager are required to bring about a successful project under this structure.

In a functional organization, the vice president or senior department manager is usually the one responsible for projects. The title of project manager denotes authority, and in a functional structure, that authority rests with the VP.

Managing Projects in a Functional Organization

Projects are typically undertaken in a divided approach in a functional organization. For example, the marketing department will work on its portion of the project and then hand it off to the manufacturing department to complete its part, and so on. The work the marketing department does is considered a marketing project, whereas the work the manufacturing department does is considered a manufacturing project.

Some projects require project team members from different departments to work together at the same time on various aspects of the project. Project team members in this structure will more than likely remain loyal to their functional managers. The functional manager is responsible for their performance reviews, and their career opportunities lie within the functional department—not within the project team. Exhibiting leadership skills by forming a common vision regarding the project and the ability to motivate people to work toward that vision are great skills to exercise in this situation. As previously mentioned, it also doesn’t hurt to have the project manager work with the functional manager in contributing to the employee’s performance review.

Resource Pressures in a Functional Organization

Competition for resources and project priorities can become fierce when multiple projects are undertaken within a functional organization. For example, in my organization, it’s common to have competing project requests from three or more departments all vying for the same resources. Thrown into the heap is the requirement to make, for example, mandated tax law changes, which automatically usurps all other priorities. This sometimes causes frustration and political infighting. One department thinks their project is more important than another and will do anything to get that project pushed ahead of the others. Again, it takes great skill and diplomatic abilities to keep projects on track and functioning smoothly. In Chapter 2 I’ll discuss the importance of gaining stakeholder buy-in, and in Chapter 5, “Developing the Project Budget and Communicating the Plan,” I’ll talk about the importance of communication to avert some of these problems.

Project managers have little authority in functional organizations, but with the right skills, they can successfully accomplish many projects. Table 1.3 highlights the advantages and disadvantages of this type of organization.

TABLE 1.3 Functional organizations

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

There is an enduring organizational structure. |

Project managers have little to no formal authority. |

There is a clear career path with separation of functions, allowing specialty skills to flourish. |

Multiple projects compete for limited resources and priority. |

Employees have one supervisor with a clear chain of command. |

Project team members are loyal to the functional manager. |

Projectized Organizations

Projectized organizations are nearly the opposite of functional organizations. The focus of this type of organization is the project itself. The idea behind a projectized organization is to develop loyalty to the project, not to a functional manager.

Figure 1.3 shows a typical organizational chart for a projectized organization.

FIGURE 1.3 Projectized organizational chart

Organizational resources are dedicated to projects and project work in purely projectized organizations. Project managers almost always have ultimate authority over the project in this structure and report directly to the CEO. In a purely projectized organization, supporting functions such as human resources and accounting might report directly to the project manager as well. Project managers are responsible for making decisions regarding the project and acquiring and assigning resources. They have the authority to choose and assign resources from other areas in the organization or to hire them from outside if needed. For example, if there isn’t enough money in the budget to hire additional resources, the project manager will have to come up with alternatives to solve this problem. This is known as a constraint. Project managers in all organizational structures are limited by constraints such as scope, schedule, and cost (or budget). Quality is also considered a constraint, and it’s generally affected by scope, schedule, and/or cost. We’ll talk more about constraints in Chapter 2.

NOTE

You may come across the term triple constraints in your studies. The term refers to scope, schedule, and cost constraints. However, please note that the PMBOK® Guide also calls constraints competing demands, and notes that the primary competing demands on projects are scope, schedule, cost, risk, resources, and quality.

Teams are formed and often co-located, which means team members physically work at the same location. Project team members report to the project manager, not to a functional or departmental manager. One obvious drawback to a projectized organization is that project team members might find themselves out of work at the end of the project. An example of this might be a consultant who works on a project until completion and then is put on the bench or let go at the end of the project. Some inefficiency exists in this kind of organization when it comes to resource utilization. If you have a situation where you need a highly specialized skill at certain times throughout the project, the resource you’re using to perform this function might be idle during other times in the project.

In summary, you can identify projectized organizations in several ways:

Project managers have high to ultimate authority over the project.

The focus of the organization is the project.

The organization’s resources are focused on projects and project work.

Team members are co-located.

Loyalties are formed to the project, not to a functional manager.

Project teams are dissolved at the conclusion of the project.

Matrix Organizations

Matrix organizations came about to minimize the differences between, and take advantage of, the strengths and weaknesses of functional and projectized organizations. The idea at play here is that the best of both organizational structures can be realized by combining them into one. The project objectives are fulfilled and good project management techniques are utilized while still maintaining a hierarchical structure in the organization.

Employees in a matrix organization oftentimes report to one functional manager and to at least one project manager. It’s possible that employees could report to multiple project managers if they are working on multiple projects at one time. Functional managers pick up the administrative portion of the duties and assign employees to projects. They also monitor the work of their employees on the various projects. Project managers are responsible for executing the project and giving out work assignments based on project activities. Project managers and functional managers share the responsibility of performance reviews for the employee.

NOTE

In a nutshell, in a matrix organization, functional managers assign employees to projects, whereas project managers assign tasks associated with the project.

Matrix organizations have unique characteristics. We’ll look at how projects are conducted and managed and how project and functional managers share the work in this organizational structure next.

Project Focus in a Matrix Organization

Matrix organizations allow project managers to focus on the project and project work just as in a projectized organization. The project team is free to focus on the project objectives with minimal distractions from the functional department.

Project managers should take care when working up activity and project estimates for the project in a matrix organization. The estimates should be given to the functional managers for input before publishing. The functional manager is the one in charge of assigning or freeing up resources to work on projects. If the project manager is counting on a certain employee to work on the project at a certain time, the project manager should determine their availability up front with the functional manager. Project estimates might have to be modified if it’s discovered that the employee they were counting on is not available when needed.

Balance of Power in a Matrix Organization

As we’ve discussed, a lot of communication and negotiation takes place between the project manager and the functional manager. This calls for a balance of power between the two, or one will dominate the other.

In a strong matrix organization, the balance of power rests with the project manager. They have the ability to strong-arm the functional managers into giving up their best resources for projects. Sometimes, more resources than necessary are assembled for the project, and then project managers negotiate these resources among themselves, cutting out the functional manager altogether, as you can see in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4 Strong matrix organizational chart

On the other end of the spectrum is the weak matrix (see Figure 1.5). As you would suspect, the functional managers have the majority of power in this structure. Project managers are really project coordinators or expeditors with part-time responsibilities on projects in a weak matrix organization. Project managers have limited authority, just as in the functional organization. On the other hand, the functional managers have a lot of authority and make all the work assignments. The project manager simply expedites the project.

FIGURE 1.5 Weak matrix organizational chart

In between the weak matrix and the strong matrix is an organizational structure called the balanced matrix (see Figure 1.6). The features of the balanced matrix are what I’ve been discussing throughout this section. The power is balanced between project managers and functional managers. Each manager has responsibility for their parts of the project or organization, and employees get assigned to projects based on the needs of the project, not the strength or weakness of the manager’s position.

FIGURE 1.6 Balanced matrix organizational chart

Matrix organizations have subtle differences, and it’s important to understand their differences for the PMP® exam. The easiest way to remember them is that the weak matrix has many of the same characteristics as the functional organization, whereas the strong matrix has many of the same characteristics as the projectized organization. The balanced matrix is exactly that—a balance between weak and strong, where the project manager shares authority and responsibility with the functional manager. Table 1.4 compares all three structures.

TABLE 1.4 Comparing matrix structures

|

Weak Matrix |

Balanced Matrix |

Strong Matrix |

Project manager’s title |

Project coordinator, project leader, or project expeditor |

Project manager |

Project manager |

Project manager’s focus |

Split focus between project and functional responsibilities |

Projects and project work |

Projects and project work |

Project manager’s power |

Minimal authority |

Balance of authority and power |

Significant authority and power |

Project manager’s time |

Part-time on projects |

Full-time on projects |

Full-time on projects |

Organization style |

Most like a functional organization |

Blend of both weak and strong matrix |

Most like a projectized organization |

Project manager reports to |

Functional manager |

A functional manager, but shares authority and power |

Manager of project managers |

Most organizations today use some combination of the organizational structures described here. They’re a composite of functional, projectized, and matrix structures. It’s rare that an organization would be purely functional or purely projectized. Projectized structures can coexist within functional organizations, and most composite organizations are a mix of functional and projectized structures.

In the case of a high-profile, critical project, the functional organization might appoint a special project team to work only on that project. The team is structured outside the bounds of the functional organization, and the project manager has ultimate authority for the project. This is a workable project management approach and ensures open communication between the project manager and team members. At the end of the project, the project team is dissolved, and the project members return to their functional areas to resume their usual duties.

Project-Based Organizations

There is one more structure we should talk about called a project-based organization (PBO). A PBO is a temporary structure an organization puts into place to perform the work of the project. A PBO can exist in any of the organizational structure types we’ve just discussed. Most of the work of a PBO is project based and can involve an entire organization or a division within an organization. The important thing to note about PBOs for the exam is that a PBO measures the success of the final product, service, or result of the project by bypassing politics and position and thereby weakening the red tape and hierarchy within the organization because the project team works within the PBO and takes its authority from there.

Organizations are unique, as are the projects they undertake. Understanding the organizational structure will help you, as a project manager, with the cultural influences and communication avenues that exist in the organization to gain cooperation and successfully bring your projects to a close.

Understanding Project Life Cycles and Project Management Processes

Project life cycles are similar to the life cycle that parents experience raising their children to adulthood. Children start out as infants and generate lots of excitement wherever they go. However, not much is known about them at first. So, you study them as they grow, and you assess their needs. Over time, they mature and grow (and cost a lot of money in the process) until one day the parents’ job is done.

Projects start out just like this and progress along a similar path. Someone comes up with a great idea for a project and actively solicits support for it. The project, after being approved, progresses through the intermediate phases to the ending phase, where it is completed and closed out.

Project Phases and Project Life Cycles

Most projects are divided into phases, and all projects, large or small, have a similar project life cycle structure. Project phases generally consist of segments of work that allow for easier management, planning, and control of the work. The work and the deliverables produced during a phase are typically unique to that phase. Some projects may consist of one phase, and others may have many phases.

The number of phases depends on the project complexity and the industry. For example, information technology projects might progress through phases such as requirements, design, program, test, and implement. All the collective phases the project progresses through in concert are called the project life cycle. Project life cycles are similar for all projects regardless of their size or complexity.

The phases that occur within the project life cycle are sequential and sometimes overlap each other. Most projects consist of the following structure (not to be confused with the project management process groups that we’ll discuss in the section “Project Management Process Groups”):

Beginning the project

Planning and organizing the work of the project

Performing the work of the project

Closing out the project

Life Cycle Categories

According to the PMBOK® Guide, there are three categories of project life cycles. Each contains the phases, or iterations, we just discussed (beginning, planning, performing, closing). The three types of project life cycles are as follows:

Predictive Cycles (Also Known as Fully Plan-Driven Approach or Waterfall) The project scope is defined at the beginning of the project and changes are monitored closely. If changes are made, you must revisit and modify plans and formally accept the changes to the scope and subsequent project management plan. The work of each phase is usually distinct and not repeated in other phases. Schedules and budgets are defined early in the life cycle as well. Each phase has an emphasis on a different portion of the project activities and different project management process groups (described a bit later) are performed during each phase.

Iterative and Incremental Life Cycles Project deliverables are defined early in the life cycle and progressively elaborated as the project progresses. Schedule and cost estimates are continually refined as the end product, service, or result of the project is more clearly defined. Iterative life cycles are a perfect choice for large projects, for complex projects (this life cycle process will reduce the complexity), for projects where changing objectives and scope are known ahead of time, or for projects where deliverables need to be delivered incrementally. Each phase requires performing all of the project management process groups.

Adaptive Life Cycles (Also Known as Agile Methods or Change-Driven Methods) Choose this method when active participation of your stakeholders is required throughout the project, when you are not certain of all the requirements at the beginning of the project, or when you work in a changing environment. This life cycle produces deliverables, or portions of deliverables, in short time periods of two to four weeks. Each iteration must produce something that is ready for release at the end of the time period, and as such, the time period and the resources are fixed. All iterations require the Planning process group and most will perform all of the project management process groups.

The end of each phase within the life cycle, regardless of the type of life cycle you are using, allows the project manager, stakeholders, and project sponsor the opportunity to determine whether the project should continue to the next phase. To progress to the next phase, the deliverable from the phase before it must be reviewed for accuracy and approved. As each phase is completed, it’s handed off to the next phase. We’ll look at handoffs and progressions through these phases next.

Handoffs

Project phases evolve through the life cycle in a series of phase sequences called handoffs, or technical transfers. For projects that consist of sequential phases, the end of one phase typically marks the beginning of the next. For example, in the construction industry, feasibility studies often take place in the beginning phase of a project and are completed prior to the beginning of the next phase.

The purpose of the feasibility study is to determine whether the project is worth undertaking and whether the project will be profitable to the organization. A feasibility study is a preliminary assessment of the viability of the project; the viability or perhaps marketability of the product, service, or result of the project; and the project’s value to the organization. It might also determine whether the product, service, or result of the project is safe and meets industry or governmental standards and regulations. The completion and approval of the feasibility study triggers the beginning of the requirements phase, where requirements are documented and then handed off to the design phase, where blueprints are produced. The feasibility study might also show that the project is not worth pursuing and the project is then terminated; therefore, the next phase never begins.

Phase Completion

You will recognize phase completion because each phase has a specific deliverable, or multiple deliverables, that marks the end of the phase. A deliverable is an output that must be produced, verified, and approved to bring the phase, life cycle process, or project to completion. Deliverables are unique and verifiable and may be tangible or intangible, such as the ability to carry out a service. Deliverables might also include things such as design documents, project budgets, blueprints, project schedules, prototypes, and so on.

A phase-end review allows those involved with the work to determine whether the project should continue to the next phase. For example, a deliverable produced in the beginning phase of a construction industry project might be the feasibility study. Producing, verifying, and accepting the feasibility study will signify the ending of this phase of the project. The successful conclusion of one phase does not guarantee authorization to begin the next phase. The feasibility study mentioned earlier might show that environmental impacts of an enormous nature would result if the construction project were undertaken at the proposed location. Based on this information, a go or no-go decision can be made at the end of the phase. Phase-end reviews give the project manager the ability to discover, address, and take corrective action against errors discovered during the phase.

NOTE

The PMBOK® Guide states that phase end reviews are also known by a few other names: phase exits, phase gates, phase reviews, milestones, stage gates, and kill points.

Multi-phased Projects

Projects may consist of one or more phases. The phases of a project are often performed sequentially, but there are situations where performing phases concurrently, or overlapping the start date of a sequential phase, can benefit the project. According to the PMBOK® Guide, there are two types of phase-to-phase relationships:

Sequential Relationships One phase must finish before the next phase can begin.

Overlapping Relationships One phase starts before the prior phase completes.

Sometimes phases are overlapped to shorten or compress the project schedule. This is called fast tracking. Fast tracking means that a later phase is started prior to completing and approving the phase, or phases, that comes before it. This technique is used to shorten the overall duration of the project.

Project phases are performed within a project life cycle, as I mentioned earlier. Project life cycles typically consist of initiating the project, performing the work of the project, and so on. As a result, most projects have the following characteristics in common:

In the beginning of the project life cycle, when the project is initiated, costs are low, and few team members are assigned to the project.

As the project progresses, costs and staffing increase and then taper off at closing.

The potential that the project will come to a successful ending is lowest at the beginning of the project; its chance for success increases as the project progresses through its phases and life cycle stages.

Risk is highest at the beginning of the project and gradually decreases the closer the project comes to completion.

Stakeholders have the greatest chance of influencing the project and the characteristics of the product, service, or result of the project in the beginning phases and have less and less influence as the project progresses.

This same phenomenon exists within the project management processes as well. We’ll look at those next.

Project Management Process Groups

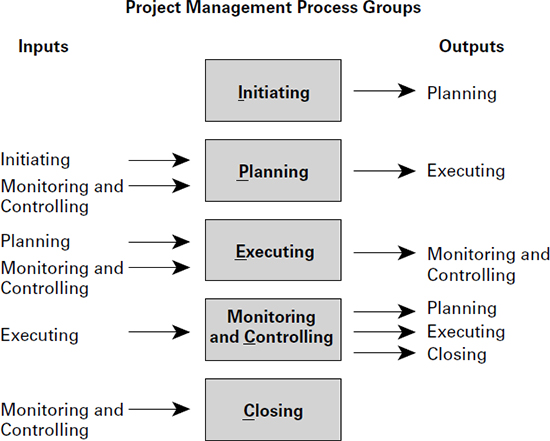

Project management processes organize and describe the work of the project. The PMBOK® Guide describes five process groups used to accomplish this end. These processes are performed by people and are interrelated and dependent on one another.

These are the five project management process groups that the PMBOK® Guide documents:

Initiating

Planning

Executing

Monitoring and Controlling

Closing

All these process groups have individual processes that collectively make up the group. For example, the Initiating process group has two processes called Develop Project Charter and Identify Stakeholders. Collectively, these process groups—including all their individual processes—make up the project management process. Projects, or each phase of a project, start with the Initiating process and progress through all the processes in the Planning process group, the Executing process group, and so on, until the project is successfully completed or it’s canceled. All projects must complete the Closing processes, even if a project is killed.

Let’s start with a high-level overview of each process group. The remainder of this book will cover each of these processes in detail. If you want to peek ahead, Appendix B, “Process Inputs and Outputs,” lists each of the process groups, the individual processes that make up each process group, and the Knowledge Areas in which they belong. (I’ll introduce Knowledge Areas in the section “Exploring the Project Management Knowledge Areas,” in Chapter 2.)

Initiating The Initiating process group, as its name implies, occurs at the beginning of the project and at the beginning of each project phase for large projects. Initiating acknowledges that a project, or the next project phase, should begin. This process group grants the approval to commit the organization’s resources to working on the project or phase and authorizes the project manager to begin working on the project. The outputs of the Initiating process group, including the project charter and identification of the stakeholders, become inputs into the Planning process group.

Planning The Planning process group includes the processes for formulating and revising project goals and objectives and creating the project management plan that will be used to achieve the goals the project was undertaken to address. The Planning process group also involves determining alternative courses of action and selecting from among the best of those to produce the project’s goals. This process group is where the project requirements are fleshed out. Planning has more processes than any of the other project management process groups. To carry out their functions, the Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing process groups all rely on the Planning processes and the documentation produced during the Planning processes. Project managers will perform frequent iterations of the Planning processes prior to project completion. Projects are unique and, as such, have never been done before. Therefore, planning must encompass all areas of project management and consider budgets, activity definition, scope planning, schedule development, risk identification, staff acquisition, procurement planning, and more. The greatest conflicts a project manager will encounter in this process group are project prioritization issues.

Executing The Executing process group involves putting the project management plan into action. It’s here that the project manager will coordinate and direct project resources to meet the objectives of the project management plan. The Executing processes keep the project on track and ensure that future execution of project plans stays in line with project objectives. This process group is typically where approved changes are implemented. The Executing process group will utilize the most project time and resources, and as a result, costs are usually highest during the Executing processes. Project managers will experience the greatest conflicts over schedules in this cycle.

Monitoring and Controlling The Monitoring and Controlling process group is where project performance measurements are taken and analyzed to determine whether the project is staying true to the project management plan. The idea is to identify problems as soon as possible and apply corrective action to control the work of the project and assure successful outcomes. For example, if you discover that variances exist, you’ll apply corrective action to get the project activities realigned with the project management plan. This might require additional passes through the Planning processes to adjust project activities, resources, schedules, budgets, and so on.

NOTE

Monitoring and Controlling is used to track the progress of work being performed and identify problems and variances within a process group as well as the project as a whole.

Closing The Closing process group is probably the most often skipped process group in project management. Closing brings a formal, orderly end to the activities of a project phase or to the project itself. Once the project objectives have been met, most of us are ready to move on to the next project. However, Closing is important because all the project information is gathered and stored for future reference. The documentation collected during the Closing process group can be reviewed and used to avert potential problems on future projects. Contract closeout occurs here, and formal acceptance and approval are obtained from project stakeholders.

Characteristics of the Process Groups

The progression through the project management process groups exhibits the same characteristics as progression through the project phases. That is, costs are lowest during the Initiating processes, and few team members are involved. Costs and staffing increase in the Executing process group and then decrease as you approach the Closing process group. The chances for success are lowest during Initiating and highest during Closing. The chances for risks occurring are higher during Initiating, Planning, and Executing, but the impacts of risks are greater during the later processes. Stakeholders have the greatest influence during the Initiating and Planning processes and less and less influence as you progress through Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing. For a better idea of when certain characteristics influence a project, refer to Table 1.5.

TABLE 1.5 Characteristics of the project process groups

|

Initiating |

Planning |

Executing |

Monitoring and Controlling |

Closing |

Costs |

Low |

Low |

Highest |

Lower |

Lowest |

Staffing levels |

Lowest |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

Chance for successful completion |

Lowest |

Low |

Medium |

High |

Highest |

Stakeholder influence |

Highest |

High |

Medium |

Low |

Lowest |

Risk probability of occurrence |

Highest |

High |

Medium |

Low |

Lowest |

The Process Flow

You should not think of the five process groups as onetime processes that are performed as discrete elements. Rather, these processes interact and overlap with each other. They are iterative and might be revisited and revised several times as the project is refined throughout its life. The PMBOK® Guide calls this process of going back through the process groups an iterative process. The conclusion of each process group allows the project manager and stakeholders to reexamine the business needs of the project and determine whether the project is satisfying those needs—and it is another opportunity to make a go or no-go decision.

Figure 1.7 shows the five process groups in a typical project. Keep in mind that during phases of a project, the Closing process group outputs can provide inputs to the Initiating process group. For example, once the feasibility study discussed earlier is accepted or closed, it becomes an input to the Initiating process group of the design phase.

FIGURE 1.7 Project management process groups

It’s important to understand the flow of these processes for the exam. If you remember the processes and their inputs and outputs, it will help you when you’re trying to decipher an exam question. The outputs of one process group may in some cases become the inputs into the next process group (or the outputs might be a deliverable of the project). Sometimes just understanding which process the question is asking about will help you determine the answer. One trick you can use to memorize these processes is to remember syrup of ipecac. This is an old-fashioned remedy for accidental poisoning that is no longer used today.

If you think of the Monitoring and Controlling process group as simply “Controlling,” when you sound out the first initial of each of the process, it sounds like IPECC (Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing).

As I stated earlier, individual processes make up each of the process groups. For example, the Closing process group consists of two processes: Close Project or Phase and Close Procurements. Each process takes inputs and uses them in conjunction with various tools and techniques to produce outputs.

NOTE

It’s outside the scope of this book to explain all the inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs for each process in each process group (although each is listed in Appendix B). You’ll find all the inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs detailed in the PMBOK® Guide, and I highly recommend you become familiar with them.

You’ll likely see test questions regarding inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs of many of the processes within each process group. One way to keep them all straight is to remember that tools and techniques usually require action of some sort, be it measuring, applying some skill or technique, planning, or using expert judgment. Outputs are usually in the form of a deliverable. Remember that a deliverable is characterized with results or outcomes that can be verified. Last but not least, outputs from one process oftentimes serve as inputs to another process.

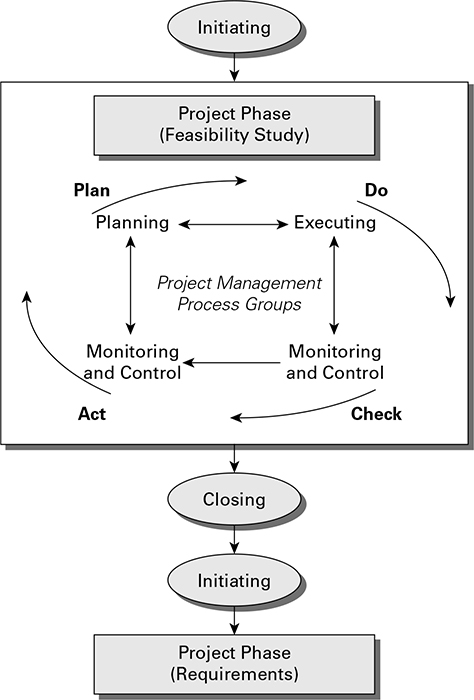

Process Interactions

We’ve covered a lot of material, but I’ll explain one more concept before concluding. As stated earlier, project managers must determine the processes that are appropriate for effectively managing a project based on the complexity and scope of the project, available resources, budget, and so on. As the project progresses, the project management processes might be revisited and revised to update the project management plan as more information becomes known. Underlying the concept that process groups are iterative is a cycle the PMBOK® Guide describes as the Plan-Do- Check-Act cycle, which was originally defined by Walter Shewhart and later modified by Edward Deming. The idea behind this concept is that each element in the cycle is results oriented. The results from the Plan cycle become inputs into the Do cycle, and so on, much like the way the project management process groups interact. The cycle interactions can be mapped to work with the five project management process groups. For example, the Plan cycle maps to the Planning process group. Before going any further, here’s a brief refresher:

Project phases describe how the work required to produce the product of the project will be completed.

Project management process groups organize and describe how the project activities will be completed in order to meet the goals of the project.

The Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle is an underlying concept that shows the integrative nature of the process groups.

Figure 1.8 shows the relationships and interactions of the concepts you’ve learned so far. Please bear in mind that a simple figure can’t convey all the interactions and iterative nature of these interactions; however, I think you’ll see that the figure ties the basic elements of these concepts together.

FIGURE 1.8 Project management process groups

Understanding How This Applies to Your Next Project

As you can tell from this first chapter, managing projects is not for the faint of heart. You must master multiple skills and techniques in order to complete projects successfully. In your day-to-day work environment, it probably doesn’t matter much if you’re working in a functional or strong matrix organization. More important are your communication, conflict management, and negotiation and influencing skills. Good communication is the hallmark of successful projects. (We’ll talk more about communication and give you some communication tips in the coming chapters.)

In any organizational structure, you’ll find leaders and you’ll find people who have the title of leader. Again, the organizational structure itself probably isn’t as important as knowing who the real leaders and influencers are in the organization. These are the people you’ll lean on to help with difficult project decisions and hurdles.

I talked about the definition of a project in this chapter. You’d be surprised how many people think ongoing operations are projects. Here’s a tip to help you explain the definition to your stakeholders: projects involve the five project management process groups (Initiating through Closing). Ongoing operations typically involve the Planning, Executing, and Monitoring and Controlling processes. But here’s the differentiator—ongoing operations don’t include Initiating or Closing process groups because ongoing operations don’t have a beginning or an end.

Most projects I’ve worked on involved more than one stakeholder, and stakeholders often have conflicting interests. On your next project, find out what those stakeholder interests are. Resolving conflicts is easier at the beginning of the project than at the end. You’ll likely need both negotiating and influencing skills.