Chapter 1. The History of Compositing

Artists have been combining drawings, photos, paintings, remnants, and found objects for centuries. The digital tools and techniques that this book describes are an important addition to the practice of envisioning, combining, and discovering images that uniquely express the subconscious and conscious. No one lives in a vacuum, least of all artists whose eyes and very beings thrive on viewing images and exploring ideas for substance and inspiration.

As artists and educators, you appreciate the importance of understanding the history, terminology, and contemporary practices of the art form in which you are a part. For example, you enjoy visiting contemporary art galleries because they inspire and inform you as to what is relevant in the contemporary arts. We’re not suggesting that you look at someone else’s work and copy it, but instead that you see how the many past and presently practicing image makers have investigated similar ideas and issues, and learn from their examples and solutions. Or as Sir Isaac Newton (1643–1727) succinctly put it, “If I have seen a little further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Appreciate where you have come from in order to know where you are going.

To create successful composites and collaged images, it is essential to value the history of compositing and understand the basic vocabulary of your chosen art form. Before we get into the nuts and bolts of Adobe Photoshop, we’ll take a brief foray into the history of combining images, discuss composite categories, and present a variety of composite work that will inspire and inform you to explore and express your unique point of view. In this chapter, you’ll:

• Be introduced to the history of compositing

• Meet influential artists

• Explore where compositing is used

• Learn about the types of composites

A Multilayered History

The history of collage and montage is rich and varied. Its roots are in the history of painting: Painters often used symbolism and metaphor to convey a thought or perception. Photography is infused with artists who use combinations of printing, montage, and collage to overcome technical limitations or expand creative expression. Digital compositing continues this history. The computer gives artists new ways to combine images from disparate sources, eras, and mediums to create new and compelling work.

Due to image copyright and licensing requirements, we cannot feature all of the historical images addressed in this chapter. We hope that the references inspire you to look up, search, and visit galleries and museums to appreciate the work of the many artists mentioned in this chapter who inspire our creativity.

Nonphotographic Collages

People have been gluing, sticking, stitching, and attaching disparate objects to a variety of surfaces for many centuries, such as adding valuable jewels and gemstones to religious artifacts and coats of arms. On a less expensive note, quilting—the art of combining cloth remnants into complex and meaningful patterns—is enjoying a true renaissance. Quilts that were once discarded are now valuable collector’s items and shown in museums. The practice of scrapbooking is also enjoying immense popularity, as young families even in this digital age gather to glue, notate, and memorialize family events, such as children’s births, first day of school, and other similar rites of passage.

In the early twentieth century Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) created artwork with discarded or found objects. Their works influenced Louise Nevelson, Joseph Cornell, and Robert Rauschenberg, who all worked with what most people at that time would consider trash to create unique artwork that has in turn influenced countless artists and achieved great critical acclaim. These artists encourage us to be inspired by source materials that are in our basements, in our garages, and even on the curb on trash day. For example, Louse Nevelson (1899–1988) created stunning sculptures out of discarded blocks of wood that she most often painted a monotone white or black. Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) created beautiful assemblage boxes that remain quirky, beautiful, and intriguing, and have motivated many artists to take a second look into the back of kitchen drawers and attics to see what hidden objects they have to tell their personal stories with. In fact, Katrin’s mother Carol (1922–present) used such objects to create her autobiographical boxes (FIGURE 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Carol Eismann’s exploration of feminine roles and identity.

Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) was an incredibly prolific artist who worked with paint, silk-screen printing, and sculpture. His multilayered approach of juxtaposing images of contemporary media across and on top of one another was a precursor to the Pop Art of the 1960s. Among his most important works are the “Combines” in which he gathered found objects and integrated them with one another to create something new. He enjoyed the use of the found object, as he perfectly expressed, “I wanted to use the generosity of finding surprises. And if it wasn’t a surprise at first, by the time I got through with it, it was. So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing.”

The next time you’re walking down the street, walk a bit slower and see what you can find to use as unique source materials. Let yourself be surprised and open to seeing and finding a wide variety of source materials for your compositing projects. Carry a camera to photograph the item on the spot, or if size and circumstance permit, you can bring the item back to the studio for more controlled photographing or scanning.

Traditional Photographic Composites

It is often said that photography liberated painting from being a medium dedicated to recording reality to being an expressive medium that allowed (although not limited to) Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism, and Abstract painting to develop and flourish. But just because painting was liberated did not guarantee that photography would or could record reality perfectly. In fact, it couldn’t. Even in the earliest days of photography, artists were exploring multiple exposures and composite images to offset physical shortcomings of the materials of the day and to express their artistic sensibilities.

In the nineteenth century, photographic materials were overly blue sensitive and couldn’t differentiate between sky and clouds, causing the skies to be very white and uninteresting. Photographers used combination printing to add skies, as Camille Silvy (1834–1910) did with his highly regarded river scenes in the 1850s. The difference clouds make to a landscape was well described by a contemporary critic of Silvy, “A sky should convey the effect of space, not surface; the eye should gaze into, not upon it; and instead of coming forward and throwing back every other object, it should retire and bring the landscape into prominence.” Landscapes without skies, with only a uniform white tone above the ground, were found wanting by critics. They lacked atmosphere. But the blue sensitive negatives of the time made landscapes with skies an almost impossible challenge.

Oscar Gustave Rejlander (1813–1875) used multiple exposures and combination printing to choreograph and create complex images, which even today would be impossible to take with a single exposure. One of the most famous examples of an early photo composite of Rejlander’s is “Two Ways of Life” (1857), which was made from over 30 glass plate negatives (FIGURE 1.2). The image portrays a sage who is guiding two young men toward adulthood. On the left a lusty young man eagerly looks at a life of wine, woman, and gambling; on the right side the young man sees a life of family, hard work, and faith. It may be difficult to comprehend, but at this time in history the sight of naked people created quite a stir. When the image was displayed in Scotland, the left side of the image was covered with a cloth. In 1860, Rejlander created a scandalous composite image called “The Bachelor’s Dream,” which portrayed a young man lying on a daybed as he fantasizes about the scantily clad and tiny woman climbing on the ribbing of a woman’s corset. Viewers were incensed by the blatant sexuality. Although Rejlander is considered the father of fine art photography, he died in absolute poverty.

Figure 1.2. Oscar Gustave Rejlander “Two Ways of Life,” 1858.

Henry Peach Robinson (1830–1901) studied with Rejlander. His images started with sketches and drawings in which he worked out complex scenes. Robinson’s pictures told stories, including the famous “Fading Away” (1858) in which a young woman is seen lying on her deathbed surrounded by her mother and sister, as the distraught father gazes out the window (FIGURE 1.3). The image struck a deep nerve in Victorian Europe, because deaths of children and young family members were personally experienced by most families. Viewers were incensed that the photographer had been privy to and profited from such a personal event, even though the image was of willing models and at least five different glass plates were combined to create the final image. Interestingly, painters at the same time also portrayed this subject without creating an uproar. Because the image was photographic—that is, realistic—viewers imbued the image with truth and related to the situation much more keenly than when a similar subject was portrayed with oil on canvas.

Figure 1.3. Henry Peach Robinson “Fading Away,” 1858.

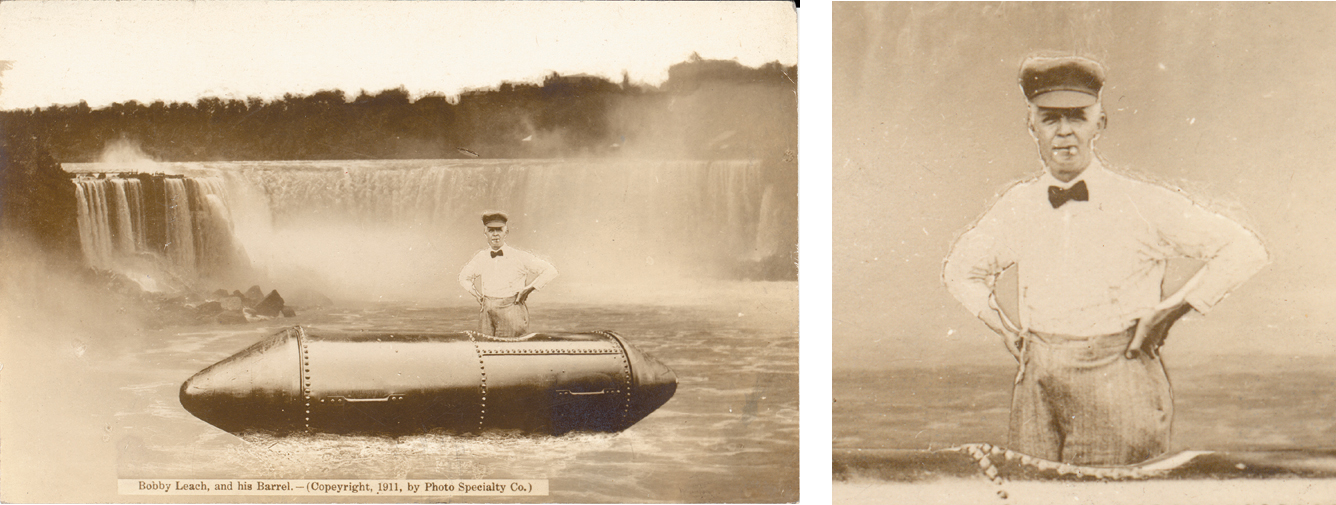

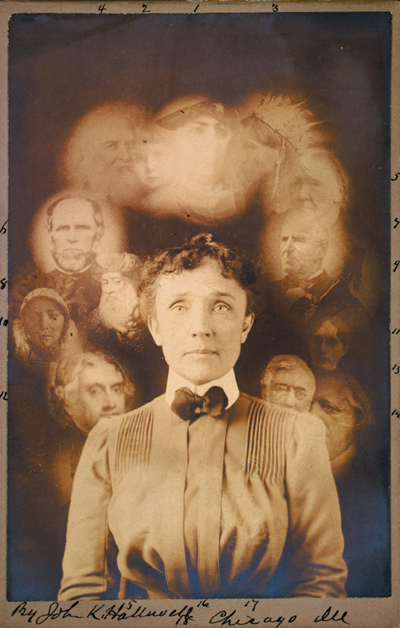

Well into the late nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, photographers were compositing or double-exposing images to create trick photos of people with two heads; people standing in boats, including Bobby Leach, who was the second person to survive going over Niagara Falls in a barrel (FIGURE 1.4); and the very popular spirit photographs, which often portrayed a seer who could communicate with the deceased who were shown floating in the background (FIGURE 1.5). Perhaps most famous are the five images of the Cottingley Fairies that were “photographed” in 1916–17 by two young girls, Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright, who lived in Cottingley, England. The photographs attracted tremendous international attention, including a book by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and being made into a movie in 1997, Fairy Tale: A True Story, with two of our favorite actors, Harvey Keitel and Peter O’Toole. As Paul Atterbury—a British antiques expert often featured on the popular television series Antiques Roadshow—stated, “These extraordinary photographs took the world by storm in 1918.”

Figure 1.4. Postcard showing a composite photograph of daredevil Bobby Leach, July 1911. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540

Figure 1.5. Spirit photo. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540

As artists and photographers, we cannot rush to judgment and quickly discount these seemingly crude attempts at photorealism with our Photoshop-induced superiority and hindsight. It is important to understand the roots of our art form and to appreciate that the times of our great-grandparents were more innocent, and in regard to photographic images, less sophisticated.

The Twentieth Century: Dada

The nineteenth century saw the dawn of photography. Much of the work was dedicated to working around technical limitations and simply showing what photography could do. It wasn’t until after World War I that artists began to use montage as a truly new art form—one that tore, questioned, and challenged existing perceptions. The Dadaists in Berlin, including Raoul Hausman, Hannah Höch, Kurt Schwitters, and John Heartfield (1891–1968), worked with photomontage to question the status quo. Of this group, Hannah Höch (1889–1978) continued working with photomontage until her death. In fact, she rejected the literal and what she deemed the tendentious political work of the group’s most well-known member, John Heartfield.

Born in 1891 as Helmut Herzfeld, Heartfield anglicized his German name to protest World War I. Not one to shy away from expressing his political views, Heartfield exposed and criticized Adolf Hitler’s reliance on German industrial wealth and the horrors of war. Heartfield and his brother Wieland Herzfeld founded the publishing house Malik-Verlag in Prague, Czechoslovakia, which provided an ideal outlet for Heartfield’s critical images as featured in the groundbreaking magazine the AIZ (Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung) or Workers Illustrated Magazine. Heartfield’s work was banned during the Third Reich and then rediscovered in the late 1950s. Since then, his powerful use of image and type has greatly influenced many artists and graphic designers. Katrin had the good fortune to visit a retrospective of John Heartfield’s work, which taught her two lessons: First, whenever possible, it is essential to see artwork in the first person, not on the web or in a book but in a gallery or museum. Second, she was fascinated by how he used mundane newspaper images and cut and pasted them into place. To create the final image, he photographed the montages and retouched the copy negatives to conceal the seams that were so obvious in the original pieces.

The Twentieth Century: Surrealism

World War 1 had soaked the European continent with blood, and the war to end all wars had forever changed the established social, political, and economic systems. The darkest, irrational aspects of war had been exposed to the world through the press and film. Taking impetus from Dada, surrealists, including the artists Man Ray (1890–1976) and Méret Oppenheim (1916–1985) as well as filmmakers Luis Buñuel (1890–1983) and Jean Cocteau (1889–1963), were part of a wide-reaching and influential art movement whose characteristics included exploring shocking juxtaposition and the surprising use of the absurd.

In the early twentieth century, Emmanuel (“Manny”) Radnitzky’s family changed its surname to Ray due to a deep fear of anti-semitism, and Manny took on the moniker of Man Ray. Man Ray had ties to both Dada and Surrealism, and although he considered himself a painter, he is most often remembered as an avant-garde photographer who created compelling photograms (images created in the darkroom on photosensitive materials without a camera). In fact, he coined the term rayographs or rayograms. The images are ethereal renderings of familiar objects, such as bottles, glasses, and scissors layered on top of one another to create images of Man Ray’s imagination. Many credit his lover and muse Lee Miller (1907–1977)—a fashion model and photographer who also explored Surrealism—with influencing Ray’s art. As the story goes, she accidentally exposed one of Man Ray’s images to light by opening the darkroom door, which resulted in the first solarized image—a technique that Ray used quite often thereafter.

Man Ray’s grave in Cimetière de Montparnasse in Paris (FIGURE 1.6) is an oft-visited site for art lovers, and as the headstone says, “unconcerned but not indifferent.”

© KE

Figure 1.6. Man Ray’s final resting place.

Serendipity, experimentation, and making mistakes are the best ways to learn. So the next time you rush to Undo a step in Photoshop, take a moment to look at it with a fresh eye and learn from it.

The list of artists and photographers influenced by Man Ray is lengthy and continues to grow. Two of Katrin’s favorites include Maurice Tabard (1897–1984) and Lucas Blalock. Tabard, a French fashion photographer, printed through multiple negatives to create images that do not exist in a recognizable space or time; Blalock, a young, contemporary photographer, frenetically and wonderfully mixes and matches subject and materials.

The Twentieth Century: Darkroom Masters

In the late 1950s, two American photographers were beginning to emerge as montage artists. Jerry Uelsmann (FIGURES 1.7 and 1.8) and Duane Michals (1932–present) composed evocative, dreamlike images with traditional black-and-white materials. Michals is best known for his image sequences that often include handwritten text. According to Michals, “to illustrate grief by taking a picture of a woman crying does not aid the observer in understanding what it is truly like to experience deep sadness. Instead, the photographer must help the viewer feel what the woman feels by tracing the woman’s pain with photographs, text, icons, or anything else that brings the audience closer to the actual experience. It’s the difference between reading a hundred love stories and actually falling in love” (www.fototv.com/duane_michals).

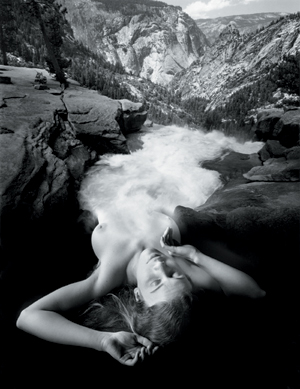

© Jerry Uelsmann

Figure 1.7. Created in the classic darkroom with multiple enlargers, Uelsmann’s images have inspired countless artists to explore combining images.

© Jerry Uelsmann

Figure 1.8. Jerry travels to Yosemite National Park on a regular basis to photograph source materials, as featured in this composite.

Both of these men, but especially Uelsmann (1934–present), created the very foundation of contemporary photomontage; in his multiple enlarger and traditional black-and-white darkroom, Uelsmann created images decades ago that many strive to create with Photoshop today.

Compositing in the color darkroom

Creating color composites required the use of pin-registration easels and hand-painted masks to print onto large-format film to create unique images. The darkroom process, as Jim explains and was a master of, often involved weeks of work to create one photo-illustration.

1. After planning the image, I would start by photographing all the elements using film formats that would integrate with each other, so that when the elements were scaled to the desired size, their grain size would match. This required a lot of planning and using a variety of cameras and film formats. For example, sometimes I would have to duplicate a 2 ¼ image up to 8×10-inch film to get the scale right.

2. I would then make a sketch by tracing the image elements onto a clear piece of 8×10-inch film and punch pin registration holes in it. Using this as a base, I would position each piece of film that was to be combined onto a separate sheet of registration-punched, black, opaque film, and then cut a small window for the image.

3. I would overlay a frisket (similar to a layer mask) of plastic adhesive film onto the image and precisely cut it to the edge of the image. Removing the waste film, I would paint around the image with black opaque, let it dry, and then remove the frisket to create a single element component.

4. For the cigarette stomp image (FIGURE 1.14), I made a mask for the cigarette, the figure, and the building by exposing a sheet of Kodalith or Pan Kodalith film with the pin-registered element on black, resulting in a clear piece of film with a black image of the element in exact registration. At this point, I had three elements—the cigarette, guy, and building—and three corresponding masks (which appear very much like the alpha channels in Photoshop), as well as the last image element—an 8×10 duplicate of the sky.

© JP

Figure 1.14. “Cigarette Stomp.”

5. To make the composite dupe while working in complete darkness, I taped a piece of 8×10 duplicating film to the vacuum easel. I started with the cigarette element, placed it over the unexposed dupe film, and made the exposure. I then placed the cigarette mask on the dupe to protect that area from being exposed again. I repeated this for each element, placing the mask onto the dupe film after each exposure. The final exposure was the sky with all the masks in place.

6. To create the edge glow, I placed several pieces of diffusion material between the mask and the dupe film. The smoke exposure was a separate exposure with no mask.

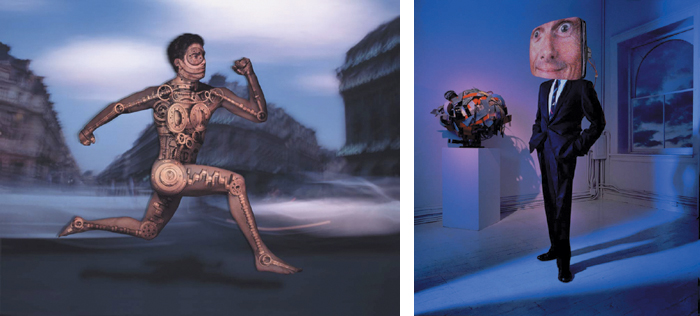

Jim concludes, “You can see how laborious this process is. This particular image took over a month to create. Given that Photoshop wasn’t showing up for at least seven or eight years, it was a nice way to get striking, conceptual, multi-image composites when almost no one was willing (or crazy enough) to make these types of images (FIGURE 1.15). The amazing thing is that all the techniques learned in the darkroom were immediately applicable to the computer; now that I’m working completely digitally, none of that experience has gone to waste as I continue to create conceptual and creative illustrations for clients such as Absolut, Adidas, Pepsi, Reebok, and Sony to name a few” (FIGURE 1.16).

© JP

Figure 1.15. James Porto darkroom-based image composites produced in the late 1980s.

© JP

Figure 1.16. Working on self-assigned projects, James Porto explored advertising and information overload, and collaborated with the Blacksnow fashion company to explore fashions via dance.

Analog to Digital History

The years ranging from the 1970s to the 1990s were a hotbed of innovation and development: Kodak and Sony were working on electronic cameras, Apple Computer was founded, and Xerox PARC was encouraging researchers to be innovative. In addition, graphical software, such as MacPaint, SuperPaint, and PageMaker, was being developed. All showed the way for the creative use of computers.

In 1987, Thomas Knoll wrote code to display grayscale images on a black-and-white bitmap computer monitor codenamed Display. At the time, his brother John was working for ILM (Industrial Light & Magic), a division of Lucasfilms founded by George Lucas of Star Wars fame. Thomas’s code caught John’s attention and he asked Thomas to write code to process digital images for the special effects industry. Within a year, Display had color capabilities, could support a variety of file formats, and featured a unique soft-edged selection that allowed for localized color and brightness enhancements. In 1988, John shopped the application around and showed it to a variety of software companies. Russell Brown, one of Adobe’s original employees, saw the potential of what was then called PhotoShop. With some additional software engineering, as well as dropping the capital S, the first version of Photoshop was released in early 1990 by Adobe Systems.

Although the early 1990s were heady times, average desktop computers couldn’t support high-resolution files, and most photographers were hesitant to give up the proven quality of film to work on low-resolution files on slow computers. Eastman Kodak, the leader in the imaging field, understood the value of education and inspiration, and created the Kodak Center for Creative Imaging (CCI) in Camden, Maine. Here, people from all around the world could take classes and workshops in digital photography, desktop publishing, and multimedia (FIGURE 1.17). Katrin had the honor of being the first intern at CCI. Looking back she sees CCI as being the digital Bauhaus where many artists, photographers, software engineers, and instructors came together to explore the possibilities of the newest digital media. Some of the notable artists and designers that came to or taught at CCI included Russell Brown, JP Caponigro, Paul Davis, Linnea Dayton, Milton Glaser, Mac Holbert, Stephen Johnson, Jeff Schewe, Jay Maisel, Graham Nash, Grant Peterson, Gary Panter, Sharon Steuer, and Lynda Weinman.

© KE

Figure 1.17. The Center for Creative Imaging as interpreted by Katrin in 1992.

The Twenty-first Century: Digital Masters

At the beginning of the twentieth century, artists worked with scissors, glue, and sandwiched negatives. By the end of the twentieth century, artists, editorial, and commercial photographers had embraced working with digital tools and techniques to combine, juxtapose, and collide images to better express themselves.

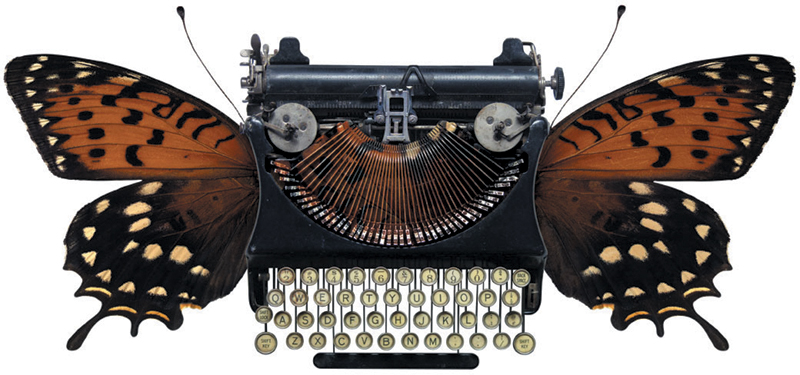

Countless contemporary artists currently use Photoshop to create artwork with great depth and character. They include Lyn Bishop, Alicia Buelow, Diane Fenster (FIGURE 1.20), Maggie Taylor (FIGURE 1.21), Simen Johan, David Julian, Viktor Koen, Julieanne Kost, Kelli Connell, Jim Kazanjian, Dorothy Simpson Krause, and Ben Gest. We are honored to share many of their techniques and approaches throughout this book. In commercial work, the images of Vincent Dixon, Aaron Goodman, Thomas Herbrich, Dave Hill, Sanjay Kothari, Mark Beckelman, Lee Varis, Nick Vedros (FIGURE 1.22), and Glen Wexler (FIGURE 1.23) shatter the boundaries of the imagination. We’ll be exploring their photorealistic techniques throughout the book. We admire and enjoy the work of all these artists and share a great respect for how they portray the world with intelligence, humor, and compassion.

© Diane Fenster

Figure 1.20. A beautiful composite by Diane Fenster that expresses the creative process.

© Maggie Taylor

Figure 1.21. Maggie Taylor uses a flatbed scanner to input image elements and then creates the collages in Photoshop.

© Nick Vedros

Figure 1.22. Nick Vedros creates images for high-end commercial and editorial clients.

© Glen Wexler

Figure 1.23. Glen created a one third-scale cow, a variety of cow wardrobes, and miniature environments for the series The Secret Life of Cows.

The Next Generation

As teachers, we continue to learn and be inspired by students in our workshops and classes. Unsurprisingly, we often tell our students, “You teach me as much as I teach you.” We are fortunate to be able to feature some of our students’ work in these pages. You too will learn from their work throughout the coming chapters as they expand and explore their art. Their work spans fashion, illustration, creative techniques, photorealism, and the completely fantastic, as shown in the work by Giselle Behrens (FIGURE 1.24), Daniel Bolliger (FIGURE 1.25), Hye-Jung Lee, Sean Basil McGiver, Jim McKenzie, Hye Ryoung Min, and Jaime Permuth (FIGURE 1.26). Mats Andersson, Joshua Cordes, and Johnny Han are fabulous examples of the young talent making big waves in the visual effects movie industry and boggling our minds with seamless visual effects, as discussed in the following section. So let’s break out the popcorn and go to the movies.

© Giselle Behrens

Figure 1.24. Image from “La Femenina” series.

© Daniel Bolliger

Figure 1.25. Creative fashion series combining studio photography with High Dynamic Range processed backgrounds.

© Jaime Permuth

Figure 1.26. Image from “The Completely Visible World” series.

Learning from Hollywood

One of the most inspiring sources to learn from about creative image compositing is the rich history of the movie industry. For example, consider what was once a state-of-the-art film—King Kong produced in 1933—to what is now considered the state-of-the-art version of King Kong as directed by Sir Peter Jackson in 2005. Anyone reading these pages knows that a giant ape that falls in love with a beautiful blonde simply didn’t exist. But as viewers, we allow ourselves to “go along” with the story as long as the illusions are believable. We flock to movies that rely on fabulous visual effects, such as Star Wars, Terminator, Apollo 13, Band of Brothers, Titanic, The Matrix, Forrest Gump, 300, Inception, Independence Day, Perfect Storm, Avatar, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and even Black Swan, in which Natalie Portman’s face was often mapped onto a professional ballerina’s body to create the illusion that the talented actress was also a highly trained prima ballerina.

Suspension of Disbelief

To appreciate visual effect movies and well-done image composites, you need to enter a willing suspension of disbelief, which allows you to consider that what you are seeing is feasible. Suspension of disbelief allows audiences to go along with the storyline while ignoring the fact that the good guy couldn’t possibly withstand such unbelievable amounts of physical punishment or leap tall buildings in a single bound. Or, as any high school physics student will tell you, exploding battleships in space do not make any noise. However, defying mere physics has never stopped a Hollywood blockbuster movie from drawing you into a good storyline.

In FIGURE 1.27 by Mark Beckelman, you know that the little girl is not holding the moon on a string. But the size relationships, lighting, and gesture allow you to experience a suspension of disbelief, which makes the image more effective. Photorealistic compositing is the bread and butter of the advertising and movie industry. In many Hollywood movie posters, the pictures of the stars are not really 100 percent pictures of the stars. Rather, a body double is shot and then the celebrity head is added in what is referred to as zippernecking.

© Mark Beckelman

Figure 1.27. This multilayered image composite plays with size relationships and the impossibility of what is being portrayed.

Appreciating that your viewer wants to believe what you are portraying in an image composite is both helpful and a responsibility to take seriously. The suspension of disbelief allows you to explore fantastic worlds while paying attention to the details. We address this creative process throughout the book as you plan the shoot and lighting, take the pictures, and then mask the elements to blend them into a new environment. Effective composites, whether surrealistic or photorealistic, require you to focus on a myriad of details to create an image that viewers will believe and enjoy rather than being distracted by disconnects in lighting, edges, scale, or color to name a few of the giveaways that can transform an effective image into an unsuccessful one. Throughout this book, we’ll discuss the many fine points that separate a poorly made mishmash image from a believable composite.

Visual Effects

Everyone can learn valuable techniques and be inspired by the big business of movies. Most likely, many of you watch a movie more than once to be able to concentrate on various aspects of it. The first time you’re usually drawn into the story, but on the second or third viewing you might take the time to study the editing, sound, or visual effects. The visual effects in today’s Hollywood smash hits are simply mind-blowing. As photographers, it makes sense to appreciate the attention to detail that goes into the visualization of a scene, motion capture, lighting, capturing actors on greenscreen, creating and matching the background plate environment, color correction, and the complexity of having the actors interact believably with computer-generated (CG), 3D characters.

Excellent examples of combining human and CG elements include the battle scenes in 300, which tells the story of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC in which the King of Sparta led his army against the advancing Persians; the 1979 science fiction thriller Alien directed by Ridley Scott in which the primary antagonist is a highly aggressive extraterrestrial creature that stalks and kills the crew of a spaceship; and on a slightly more peaceful note, the Lord of the Rings, directed by the Oscar-winning Sir Peter Jackson—a tour de force using forced perspective, visual effects, and excellent acting to hold audiences rapt and wanting more.

Chroma Key

Chroma key, also referred to as greenscreen or blue-screen, was developed when movies were still shot on analog film. It requires the actor to be captured in a greenscreen studio and then matted together with CG or historical background plates, for example, to allow Forrest Gump played by Tom Hanks to be combined with actual news film of President Kennedy. Or on a less spectacular note, your local weather reporter is shot on a bluescreen while standing in front of a changing weather map. We’ll address working with greenscreen in Chapter 4, “Lighting and Backgrounds,” and explain how to mask images shot on greenscreen in Chapter 11, “Fine-edged Selections.”

Animation

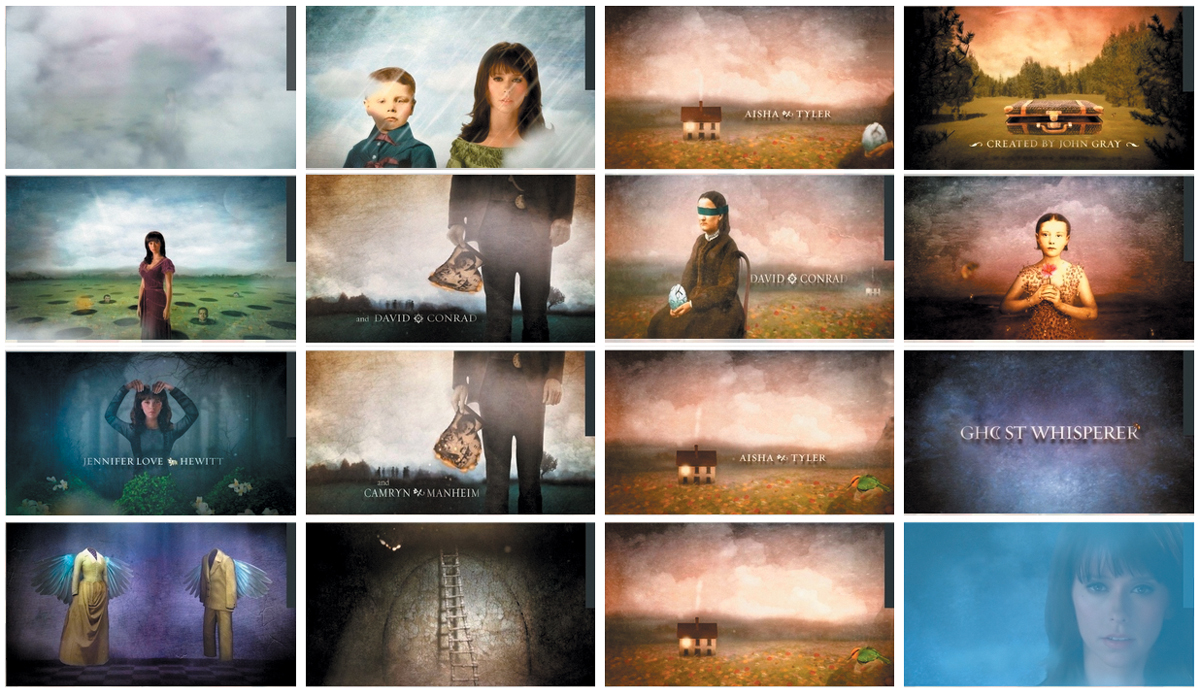

Although this isn’t a book on masking and compositing for motion, we do feel it is important to recognize and learn from the masters of composite animation. In Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Terry Gilliam created fabulous and often absurd animated collages. On a more contemporary note, the first episodes of South Park were created with paper cutouts, and the political cartoons by JibJab burst onto the scene in 2004 with a viral parody of the presidential elections. To come full circle in terms of beautiful Photoshop work and animation, the best reason to have watched the television show Ghost Whisperer starring Jennifer Love Hewitt was the opening credits based on Maggie Taylor’s artwork, which was animated by Digital Kitchen (FIGURE 1.28).

© Maggie Taylor

Figure 1.28. The original images used as source material for the opening credits of Ghost Whisperer.

Mute the sound the next time you’re watching a visual effects movie, television show, or commercial to focus on the visual effects. Observe how camera positions are matched, study the relationship between foreground and background, and pay attention to color matching.

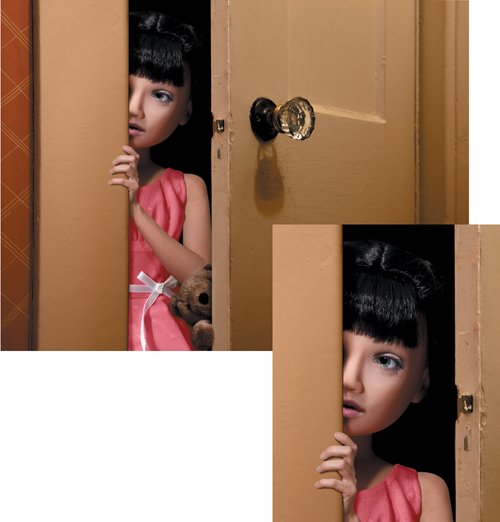

Uncanny Valley

Uncanny valley is a theory of robotics that evokes a response of revulsion in viewers when robots look and behave too much like humans. Or said less academically, it’s just creepy when the artificial crosses the line of believability. As an artist, you can use that line to great effect. Stay on the human side of the line or cross it, but do it consciously as Hye-Jung Lee did when she composited herself onto a doll figure to blur the line of real and unreal (FIGURE 1.29). Images that apply the principles of uncanny valley always require a second look to determine whether the figure is in fact a robot or a human.

© Hye-Jung Lee

Figure 1.29. Hye-Jung illustrated The Art of War with an adventurous doll-girl who was a wise warrior.

Compositing Terminology and Categories

An appreciation for the history and terminology of your chosen field is the foundation for clarity of thought, understanding, and communication. The following section contains the terminology and the types of composites in an historical and artistic context. As with many artistic concerns, some of the definitions we present are not 100 percent clear-cut because visual language evolves, and many art movements overlap one another. Consider the following terms and categories as a starting point for further exploration in the rich world of art history and art criticism.

Traditional Methods

The great majority of the art we feature in this book has been created with digital technology, but many artists build upon or are inspired by pre-digital art forms and movement as presented here:

• Alternative processes. Traditionally refers to photosensitive nonsilver processes, including cyanotypes, gum bichromate, and platinum prints. Digital alternative processes refer to gel transfers, lifts, and combination printing—all of which can add a unique layered or textural look to your final prints (FIGURE 1.30).

© Catherine Steinman

Figure 1.30. Experimenting with print media and after print treatments creates beautiful textures and layering results.

• Assemblage. Combining natural or man-made materials that are originally not intended as art objects. Hans Neleman and Viktor Koen are masters of assemblage. Hans carefully arranges image elements to photograph, and Viktor creates digital composites of the oddest subject matter to create fantastic bugs, beings, and scenarios (FIGURE 1.31), as addressed in Chapter 10, “The Power of Channel Masking.”

© Viktor Koen

Figure 1.31. Creating fantastic and surreal figures out of the detritus of modern life.

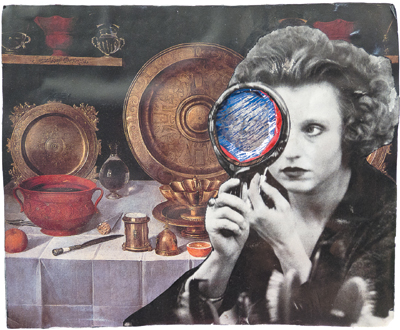

• Collage. Based on the French word coller—meaning to glue—collage artists use preexisting text, diagrams, drawings, photographs, and found objects to create quirky and intriguing images (FIGURE 1.32). The previously mentioned Dada artists Hannah Höch and John Heartfield are excellent examples of collage artists.

© Philip Eismann

Figure 1.32. Katrin’s brother, Philip, enjoys creating beautiful mixed media collages.

• Composite. Combining, blending, and creating a new image from two or more photographic source images. This entire book is filled with examples of image composites that we hope inspire you to explore and create your own image composites.

• Decoupage. Gluing paper, photos, or gold leaf onto 3D objects, often a piece of furniture, and then applying multiple coats of varnish to seal the artwork. Juan Gris (1887–1927) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1972) explored decoupage as sculpture and also subjects for Cubist paintings.

• Double exposure. Traditionally a film-based photographic technique in which the film was exposed more than once to create ghostly and surprising images. Admittedly, when using film, we sometimes unintentionally double expose a roll of film, which sometimes results in a disappointment or in a pleasant surprise (FIGURE 1.33). The serendipity of the double exposure look is often mimicked when exploring layering images with Photoshop blend modes, as we’ll address in Chapter 8, “Layer Essentials” and Chapter 13, “Creative Compositing.” Tierney Gearon, a contemporary fashion photographer, uses film double exposures, which inspired Hye-Ryoung Min’s Photoshop created composites (FIGURE 1.34).

© SD

Figure 1.33. A deliberate double exposure that was processed and enhanced in Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop.

© Hye-Ryoung Min

Figure 1.34. Digital composite inspired by the look of film-based double exposures.

• Encaustic. Applying hot beeswax and resin onto paintings or prints, including inkjet prints, to create a moody textured surface that appeals to those who appreciate the more organic, less technical feel of their final output. See www.rfpaints.com for supplies and information.

• Mixed media. Combining a variety of found materials with painting or drawing to create a new image. Digital artist Dorothy Simpson Krause explores mixed media by creating the initial image in Photoshop and then printing on brushed aluminum, fresco, or nonwoven cloth (FIGURE 1.35).

© Dorothy Simpson Krause

Figure 1.35. From the series “Visions,” which explores the spiritual transitions and ultimately life and death.

• Montage. Using the juxtaposition of disparate elements to create seamless and (often) surreal images. Examples of the montage approach can be found in mediums other than photography, for example, in the paintings of surrealists Salvador Dali and René Magritte. Often used interchangeably with collage, digital montage artists experiment with layers and blend modes to create playful and surprising images.

• Scanography. Using a flatbed scanner as the surface to build up and create images on. For example, Maggie Taylor uses a flatbed scanner to capture source materials, including Victorian photos and paper textures.

• Superimpose. Projecting or layering images on top of one another. Recently, artists have been superimposing historical images onto contemporary scenes by holding a print or smartphone up to the original scene and taking a new photo or using Photoshop to combine the two. Michael Morrison, a New Yorkbased fashion photographer, created a beautiful project—“Gaze”—by photographing models and then projecting clothing onto them that concentrated on portraying vanity as both art and commerce (FIGURE 1.36).

© Michael Morrison

Figure 1.36. Michael Morrison explores contemporary fashion photography.

Study and research the wide variety of traditional and mixed media composites and re-create the look and feel with digital tools to create your own artistic images.

Working Subjectively or Conceptually

You may be drawn to a specific type of photo composite, or you may be hired to create a certain type of image. Being conversant in the related terminology allows you to work with greater intent and express yourself more clearly.

Subjective Creative

The subjective-creative approach to create images involves experimentation, being open, and learning from your images as they progress. When we have some rare free time, we’ll all just doodle. Seán calls this enjoying some Photoshop sandbox time. We’ll layer files on top of one another and explore the resulting juxtapositions by changing layer blend modes and opacities. Often, the results are just fun scribbles that we don’t save, but sometimes we create images that we really like. We’ll delve into subjective-creative composites in Chapter 13, ”Creative Compositing.” Adding textures, clouds, or colors to images using Photoshop is an ideal way to play on a rainy afternoon or during a travel delay (FIGURE 1.37).

© KE

Figure 1.37. Playfully combining and experimenting with images is a great way to make artistic discoveries.

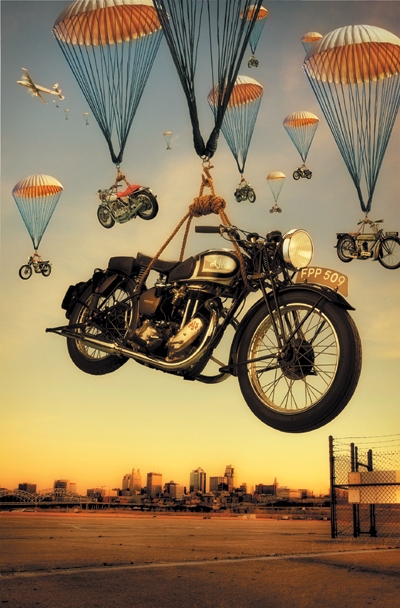

Conceptual illustrative

Illustrative composites convey an idea or concept and are frequently used to illustrate editorial articles, create features on book covers, or produce advertising campaigns when expressing an intangible idea is best portrayed with a created image rather than a straightforward photograph. Nick Vedros creates illustrative composites in situations when taking a photograph is simply impossible or when the subject defies physics, as shown in FIGURE 1.38 in which the motorcycles lightly float down on parachutes.

© Nick Vedros

Figure 1.38. The color treatment enhances the mood.

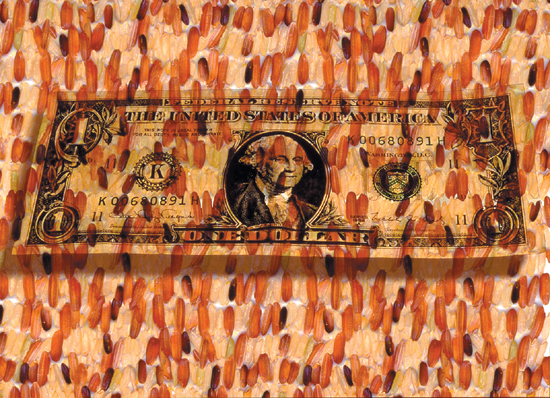

Illustrative composites start with an idea or a brief from a client. It is then up to the photographer or compositing artist to sketch possible solutions, gather or photograph the required pieces, and then combine the pieces to create the final illustration. Of course, fine artists also create conceptual illustrations, as Katrin did to illustrate the fact that almost one in seven people, represented by the multicolored grains of rice, live on less than one dollar a day (FIGURE 1.39). The question as to where artists get their ideas is an endless topic of speculation, theory, anxiety, and sleepless nights. We’ll discuss some ideas and exercises on creativity in Chapter 2.

© KE

Figure 1.39. Katrin often draws inspiration and ideas from social issues.

Surrealism

Earlier in this chapter, surrealism was addressed in an historical context, but the term surreal and/or surrealism is still a vibrant part of contemporary art-making vocabulary and practice. A surrealistic image contains non sequitur elements, which are elements or meanings that have no logical relationship with one another (FIGURE 1.40). This non sequitur aspect is emblematic of images that are surprising and perhaps shocking with unexpected juxtapositions. Salvador Dali (1904–1989) was the classic surrealist as his most famous painting, “The Persistence of Memory,” of melting clocks shows. The works of photographer Ryzard Horowitz (1939–present) show a strong surreal influence that juxtaposes scale, source materials, and environments to create highly stylized commercial work (FIGURE 1.41).

© KE

Figure 1.40. A surreal image of a headless saint offering an apple to the viewer.

© Ryzard Horowitz

Figure 1.41. Experimenting with scale and environment to create surreal images.

Photorealism

Photorealistic composites are meant to convey an illusion of reality, and although some may be surreal in nature, they are so well done that the viewer partakes in the suspension of disbelief to “believe” that they are real. Photoreal work requires detailed preproduction, precise photography, and pixel-level compositing to create engaging illusions that are so meticulously done that you just want to believe them. Such photorealistic achievements can be seen in the fabulous images of Rick Walstrom, Jim Porto, and Nick Vedros.

Of all the types of Photoshop composites, photoreal work requires the most planning, attention to detail during the photo shoot, and fastidious Photoshop skills to mask, combine, and balance the image components to transform many into one. Essential issues to focus on to create the illusion of reality include (but are not limited to) matching scale, perspective, color, light, shadows, reflections, edges, and texture. For more information on photorealism composites, see Chapter 13, “Photorealistic Compositing.”

3D and visual effects

Photography has always portrayed the 3D world on a 2D surface—be it on the sensor, film plane, or print. Once the 3D world is flattened to 2D, the camera’s point of view, lighting, and perspective are set. In the computer 3D world, nothing is ever set, and the artist can change the camera’s position, light quality and sources, surface characteristics, and reflectivity. The power is intoxicating and requires that photographers learn new skills to work with dedicated 3D software, such as Maya, 3ds Max, and Alias ImageStudio. Photographers with the perseverance to learn new skills are rewarded by being able to create fantastic images that often combine the mechanical, such as cars, or fantasy environments with natural textures or human models, as Sanjay Kothari and Mike Campau do so effectively.

Closing Thoughts

Learning about the history and terminology of photomontage is a great starting point, because knowing where your art form has been will help you understand where your artwork is going. So grab your mouse and let’s dive into mastering the tools and techniques you’ll use to create the images in your imagination.