Chapter 3

Practicing the Praxis: Sampling Some Practice Questions

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Trying your hand at some sample Praxis questions

Trying your hand at some sample Praxis questions

![]() Checking out the right and wrong answers

Checking out the right and wrong answers

![]() Determining the areas where you need to study

Determining the areas where you need to study

If you’re just beginning to prepare to take the Praxis, this chapter is a good place to start. It gives you a sense of the types of math, reading, and writing questions you’ll encounter when you face the real exam.

In this chapter, we give you an opportunity to see where your strengths and weaknesses lie. You can determine whether you need to spend the next few weeks studying statistics and probability questions, grammar rules, or reading comprehension strategies. Or maybe you’ll decide that you just need to fine-tune one or two specific areas of knowledge, and that’s fine too.

Going through the Pre-Assessment Questions

In just a minute here, we’ll be tossing some practice questions at you. Actually, because there are complete practice tests later in the book, maybe you should think of these upcoming questions as “practice for the practice.” The questions in this chapter can help you determine your strengths and weaknesses, and then align your study appropriately.

When you answer the questions in the upcoming sections, we don’t recommend setting a timer or anything like that yet. You should learn how to do something right before you start to worry about doing it fast, and there’ll be plenty of time to time yourself later.

Because time won’t be an issue, you also don’t need to worry about skipping hard questions and coming back to them later. Try your best to answer each one, even if it’s just a guess (there’s no penalty for guessing on the Praxis, so on the actual test, there’ll be no reason to leave a question blank).

Finally, we recommend that you resist the urge to flip to the answers after each question to see whether you got it right. That can wait until you’ve completed all the practice questions. Seeing that you’ve gotten a few questions wrong early on can dishearten you, and seeing that you’ve gotten a bunch right in a row can make you paranoid about jinxing yourself. Either way, there’s no advantage to checking your answers on a question-by-question basis: Take your time and complete all the questions to the best of your ability. You can worry about how many you got right when you’re finished, and you can worry about how fast you are later in the book.

(Note: We don’t provide essay questions in this chapter for you to practice on because we want you to get an overview of your skills. If you want to spend some time on essay writing, flip to Part 4.)

When you’re ready to try your hand at a full-length practice test, head to Part 5, where you’ll find two full-length Praxis exams (with essay questions included).

Reading practice questions

Although “an elephant is an elephant” to the untrained eye, African elephants and Asian elephants are actually two distinct species, and it’s not so hard to tell the difference. In African elephants, the head is higher than the back, whereas the Asian elephant’s back is higher than its head. Among African elephants, both males and females are almost always born with tusks, while female Asian elephants are usually tuskless. If you can get close enough to examine the trunk, you’ll notice that African elephants have two finger-like protrusions at the tip of the trunk, as opposed to an Asian elephant’s one.

1. According to the passage, an elephant with no tusks is

(A) definitely a female elephant.

(B) definitely an Asian elephant.

(C) probably a male Asian elephant.

(D) probably a female Asian elephant.

(E) more likely to be a male Asian elephant than a female African elephant.

Nowadays, most people are aware that Christopher Columbus was not only a pretty terrible guy, but that he also didn’t really discover America. Even leaving out the obvious objection that vast populations of indigenous peoples were already living here, there’s also indisputable evidence that the Vikings reached North America and established settlements centuries before Columbus (it was a quicker and an easier trip for them, however, as all they had to do was sail along the ice of the Arctic Circle as though it were a coastline). What far fewer people know is that it seems likely that seafaring Pacific Islanders reached the west coast of South America in the early second millennium, possibly even before the Vikings touched down in the Northeast. Archaeological evidence indicates the sudden appearance of yams (originally native to South America) in Polynesia and of chickens (originally native to Asia) in Chile at about the same time.

2. The primary purpose of the passage is to

(A) explain how chickens appeared in South America.

(B) discern whether the Vikings or Pacific Islanders reached the Americas first.

(C) argue that Columbus Day should no longer be celebrated as a holiday.

(D) examine the question of whose journey to the Americas was most difficult.

(E) provide information about journeys to the Americas before that of Columbus.

Though many might understandably assume that it was a long and complex process, the transformation of the Republican Party from a single-issue organization dedicated to ending slavery into the “party of big business” was both predictable and more-or-less instantaneous. Knowing that freed slaves would have no choice but to travel north and take factory jobs, which would result in more competition for employment and therefore lower wages, northern industrialists joined forces with idealistic abolitionists. When slavery ended, the abolitionists considered their duty done and got out of politics, and the captains of industry were left in charge of the party.

3. The passage characterizes the shift in priorities of the 19th-century Republican Party as

(A) very nearly inevitable.

(B) the surprising result of a long struggle.

(C) the fault of naïve abolitionists.

(D) a logical reaction to unforeseen circumstances.

(E) an attempt to reduce competition for employment.

It is arguably Shakespeare’s finest comedy, but modern productions of As You Like It find themselves awkwardly having to negotiate a plot point that doesn’t sit right with contemporary audiences: In this day and age, we roll our eyes at the idea that the intelligent, resourceful, and independent heroine Rosalind would fall madly in love with Orlando simply because she sees him win a wrestling match.

4. The author of the passage uses the word negotiate most nearly to mean

(A) imperceptibly alter

(B) make the best of

(C) draw attention away from

(D) apologize for

(E) rush through safely

Perhaps no issue in popular music divides both critics and fans more bitterly than the seemingly endless debate over what music, and which bands, do or do not count as “punk rock.” People can’t even seem to agree on whether punk is a genre of rock or was a historical movement within rock, specific to a particular place and time. Were 1990s rock groups like Nirvana and Blink-182 punk bands, or were they only bands that were influenced by punk as it was “authentically” played in the 1970s by bands like the Ramones and the Clash? Did punk “end” at a certain point in music history, and if so, then when, and what case is to be made for saying it ended then as opposed to at an earlier or later date? After all, if a word refers only to a style of music, then music of that style can be played by anyone at any time — but if the word refers to a contextualized historical movement, then calling contemporary bands “punk” would be as absurd as calling contemporary feminists “bluestockings” or calling contemporary Midwesterners “settlers.”

5. The organization of the passage can best be described by which of the following?

(A) A compromise between two sides in a controversy is suggested.

(B) A popular misconception is corrected.

(C) A tricky question is analyzed for a general audience.

(D) A comparison is made between seemingly dissimilar things.

(E) A problematic term is suggested to be meaningless.

I don’t feel old, but when I examine all the data, it seems to point to the fact that I just might be. Perhaps the most crucial piece of evidence is that I haven’t dressed up for Halloween in nearly four years. This wasn’t a decision I made; it was just a string of bad luck. One year, I happened to be moving on Halloween. The next year, I was helping a friend move. Last year, there was a hurricane — surely that’s not my fault, right? I can make all the excuses I want, but deep down inside I know that if I were ten years younger I would have found a way to dress up on Halloween no matter what. Maybe that’s what getting old is: a loss of energy disguised as a series of coincidences.

6. In the passage, the author’s tone can best be described as one of

(A) nostalgic self-justification.

(B) annoyed defensiveness.

(C) paranoid hypothesizing.

(D) blissful ignorance.

(E) melancholy philosophizing.

Despite the hand-wringing that intellectuals love to do about the blockbuster sales of “silly” books like The DaVinci Code, one might justifiably make the claim that we are currently living in a golden age of literature — not because more “good” books are being written, but merely because far more books of any kind are being read, and by more people, than at any point in history so far. Most studies indicate that about as many “serious” books by “good” authors are being written now as at any other time and that they are being read by about as many people. It’s just that they are no longer the most famous books. But the reason behind this is actually cause for celebration: Classes of people that would have been either illiterate or at the very least uninterested in reading in former times are now buying and reading books. Even the success of the much-maligned Twilight series should be putting smiles on the faces of those who look at it the right way: Young people are reading books of their own free will, outside of school. Granted, they’re not reading Shakespeare, but it wasn’t so long ago that they wouldn’t have been reading at all.

7. The phenomenon characterized by the author as “cause for celebration” is

(A) the fact that fewer people are making silly distinctions about what does or doesn’t count as a “serious” book.

(B) the fact that reading is popular enough among the masses for bad books to be outselling good ones.

(C) the fact that young people are reading without being forced to.

(D) the fact that maligned books like The DaVinci Code and the Twilight series are actually not as bad as many people claim.

(E) the fact that people who are uninterested in reading are reading books anyway, because there is suddenly social pressure on them to do so.

Writing practice questions

1. Don’t ![]() when the cat head-butts

when the cat head-butts ![]() should

should ![]() a sign

a sign ![]() .

. ![]() .

.

2. When I ![]() covered in

covered in ![]() naturally assumed

naturally assumed ![]() the person

the person ![]() I mailed all those ducks.

I mailed all those ducks. ![]() .

.

3. ![]() seems to have a

seems to have a ![]() as far as I can

as far as I can ![]() for us to remove it without any

for us to remove it without any ![]() lost.

lost. ![]() .

.

4. ![]() remarkable

remarkable ![]() you are not

you are not ![]() are still

are still ![]() one-on-one basketball game.

one-on-one basketball game. ![]() .

.

5. Coulrophobia is the fear of clowns, and a phenomenon more widespread than many realize.

(A) Coulrophobia is the fear of clowns, and a phenomenon more widespread than many realize.

(B) Coulrophobia, it is the fear of clowns, a phenomenon more widespread then many realize.

(C) Coulrophobia, the fear of clowns, is a phenomenon more widespread than many realize.

(D) Coulrophobia, which is the fear of clowns, being a phenomenon more widespread then many realize.

(E) Coulrophobia is the fear of clowns, it is a phenomenon more widespread than many realize.

6. The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal, they can solve mazes amazing skillfully.

(A) The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal, they can solve mazes amazing skillfully.

(B) The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal, that can solve mazes amazing and skillful.

(C) The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal, it can solve mazes amazingly skillful.

(D) The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal; which can solve mazes amazingly skillfully.

(E) The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal: It can solve mazes amazingly skillfully.

7. Although it was believed for years that they weren’t, biologists have recently proven that pandas are in fact true bears.

(A) Although it was believed for years that they weren’t, biologists have recently proven that pandas are in fact true bears.

(B) Although it was believed for years that they weren’t, but biologists have recently proven that Pandas are in fact true bears.

(C) Although it was believed for years that they weren’t, biologists have recently proven that Pandas are in fact true Bears.

(D) It was believed for years that they weren’t, however, biologists have recently proven that Pandas are in fact true bears.

(E) It was believed for years that they weren’t, biologists have recently proven that pandas are in fact true bears.

8. Whomever parked the car, that is in the driveway, could of done a better job.

(A) Whomever parked the car, that is in the driveway, could of done a better job.

(B) Whoever parked the car that is in the driveway could have done a better job.

(C) Whoever parked the car that is in the driveway, could of done a better job.

(D) Whomever parked the car which is in the driveway could have done a better job.

(E) Whomever parked the car, which is in the driveway, could have done a better job.

Mathematics practice questions

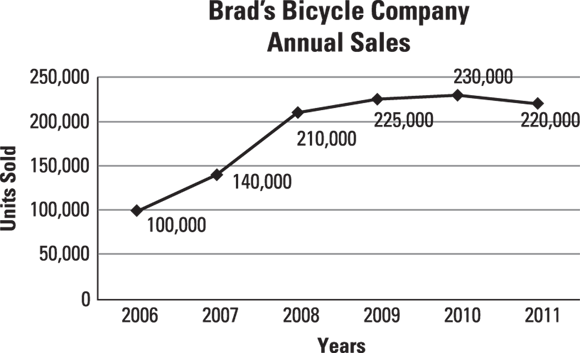

The following graph shows the number of bicycles sold by Brad’s Bicycle Company for the years 2006–2011. Use the graph to answer Questions 1–4.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

1. Which year showed the greatest number of bicycles sold by Brad’s Bicycle Company?

(A) 2006

(B) 2007

(C) 2008

(D) 2009

(E) 2010

2. Between which two years did the number of bicycles sold change the most?

(A) 2006–2007

(B) 2007–2008

(C) 2008–2009

(D) 2009–2010

(E) 2010–2011

3. What is the average number of bicycles sold for the six-year period?

(A) 1,125,000

(B) 11,250

(C) 19,000

(D) 187,500

(E) 18,750

4. What is the median number of bicycles sold for the six-year period?

(A) 210,000

(B) 220,000

(C) 215,000

(D) 430,000

(E) 225,000

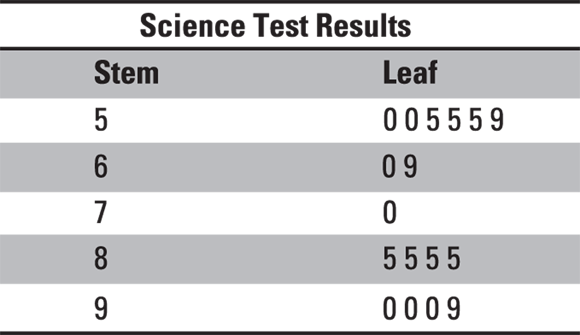

Following are the results from Mrs. Lowe’s science test. Use the stem-and-leaf plot to answer Questions 5–7.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

5. In which interval did most students score?

(A) 50–59

(B) 60–69

(C) 70–79

(D) 80–89

(E) 90–99

6. What is the median score on the math test?

(A) 60

(B) 65

(C) 70

(D) 85

(E) 90

7. What is the mode of the data set?

(A) 85

(B) 55

(C) 90

(D) 95

(E) 50

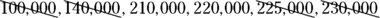

Use the Venn diagram that follows to answer Questions 8 and 9.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

8. Pizza is the favorite food of what percentage of students in the Venn diagram?

(A) 46 percent

(B) 40 percent

(C) 10 percent

(D) 23 percent

(E) 4 percent

9. What percentage of students do not like pizza or hamburgers?

(A) 46 percent

(B) 40 percent

(C) 10 percent

(D) 23 percent

(E) 4 percent

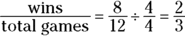

10. The Hornet football team won eight football games and lost four games. Find the ratio of wins to total games in simplest form.

(A) 8:4

(B) 2:1

(C) 1:4

(D) 2:3

(E) 4:12

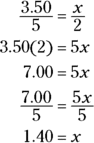

11. A grocery store sells 5 pounds of apples for $3.50. How much would you pay for 2 pounds of apples?

(A) $0.70

(B) $0.75

(C) $1.40

(D) $1.50

(E) $1.43

12. Which problem situation could be solved with the following equation?

15d + 50 = m

(A) Cassie earns $15 each day she works plus a flat rate of $50 per month. What is m, the total amount she earns in a month when she works d number of days?

(B) Cassie earns $15 for every purchase she sells at her job. What is m, the total amount she earns in 100 months?

(C) Cassie earns $50 each day she works plus a flat rate of $15 per month. What is m, the total amount she earns in a month when she works d number of days?

(D) Cassie earns d amount of dollars for every 15 items she sells. She makes $50 per day at her job. What is m, the total dollar amount Cassie earns in a year?

(E) Cassie earns d amount of dollars for every 50 items she sells. She makes $15 per day at her job. What is m, the total dollar amount Cassie earns in a year?

13. There are 10 yellow counters and 15 red counters in a bag. What is the probability of picking a yellow counter from the bag?

(A) 5/8

(B) 1/2

(C) 2/5

(D) 2/3

(E) 3/8

14. A spinner with the numbers 1 through 15 is spun. What is the probability of the spinner landing on a prime number?

(A) 2/5

(B) 5/15

(C) 6/15

(D) 3/5

(E) 7/15

15. The approximate mass of a dust particle is 0.000000000753 kilograms. Write this number using scientific notation.

(A) ![]()

(B) ![]()

(C) ![]()

(D) ![]()

(E) ![]()

16. In the following rectangle ABCD, ![]() is 6 inches long. If the rectangle’s perimeter is 34 inches, how many inches long is

is 6 inches long. If the rectangle’s perimeter is 34 inches, how many inches long is ![]() ?

?

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

(A) 28

(B) 13

(C) 22

(D) 11

(E) 17

17. What is the length in centimeters of the hypotenuse of a right triangle with legs of 5 centimeters and 12 centimeters?

(A) 13

(B) 17

(C) 7

(D) 4.12

(E) 5

18. The length of each leg of an isosceles triangle is 17 centimeters, and the perimeter is 62 centimeters. What is the length of the base?

(A) 45

(B) 17

(C) 28

(D) 14

(E) 20

19. Simplify ![]() .

.

(A) ![]()

(B) ![]()

(C) ![]()

(D) ![]()

(E) ![]()

20. Which number is NOT expressed in scientific notation?

(A) ![]()

(B) ![]()

(C) ![]()

(D) ![]()

(E) ![]()

Looking at the Pre-Assessment Answers

Now it’s time to see how you did on the three sets of practice questions. When you score your answers, keep track of which questions you answered incorrectly. Then go back and determine which category the question fits into (algebra, subject-verb agreement, and so on). This will allow you to determine those areas in which you need to spend more time studying.

Reading answers and explanations

Use this answer key to score the practice reading questions in this chapter. The answer explanations give you some insight as to why the correct answer is better than the other choices.

D. probably a female Asian elephant. The passage explicitly states that “female Asian elephants are usually tuskless.” While the passage implies that it’s possible for a male or female of either elephant species to be born without tusks, it remains the case that only female Asian elephants are tuskless most of the time.

Choice (A) is wrong because there’s no reason to think that a tuskless elephant is definitely female. The passage states that female Asian elephants are usually tuskless, but it also mentions that female African elephants usually have tusks, and that it’s possible, though rare, for a male of either species to be tuskless. (As a general rule, on reading-comprehension tests like the Praxis, you should never go for a “definitely” when a “probably” will do.)

Choice (B) is wrong because the passage states that “among African elephants, both males and females are almost always born with tusks.” The “almost” implies that it’s possible, though rare, for an African elephant of either gender to be tuskless.

Choice (C) is wrong because, although male Asian elephants are not explicitly stated to be either tusked or tuskless, the construction of the sentence “Among African elephants, both males and females are almost always born with tusks, while female Asian elephants are usually tuskless” clearly implies that male Asian elephants usually have tusks.

Choice (E) is wrong because the structure of the sentence “Among African elephants, both males and females are almost always born with tusks, while female Asian elephants are usually tuskless” implies that both male Asian and female African elephants have tusks most of the time. Although the passage does not say that it isn’t the case that a male Asian elephant is more likely to be tuskless than a female African elephant, it also doesn’t say that it is the case. This answer choice tries to trick you into going for an unsupported complex answer even though another, simpler answer choice is much more soundly supported by the passage. Don’t be fooled!

E. provide information about journeys to the Americas before that of Columbus. Look at it this way: Does the passage “provide information about journeys to the Americas before that of Columbus?” Yes, indisputably. And is it doing this pretty much the whole time? It sure is. So there’s no real way that Choice (E) can be wrong. There’s no reason to go for an overly specific answer choice when another answer choice contains a broad statement that isn’t wrong.

Choice (A) is wrong because, although the passage does provide an explanation of how chickens ended up in South America, this is not the primary purpose of the passage — it’s a detail brought up in the course of exploring a larger idea. If something isn’t brought up until the end, it’s probably not the primary purpose of the passage. (Did you notice how the passage closed with the chicken detail and then that detail was mentioned in the first of the wrong choices so it would be fresh in your mind? Watch out for that trick!)

Choice (B) is wrong because, although the passage does seem to be unsure about whether Vikings or Pacific Islanders reached the Americas first (“possibly even before …”), it doesn’t seem to be primarily concerned with which of them “won.” The passage only seeks to establish that both the Vikings and the Pacific Islanders got here before Columbus.

Choice (C) is wrong because, although it may be logical to assume that the author isn’t a big fan of Columbus Day, based on the fact that he calls Columbus a “terrible guy” and points out that he didn’t really discover America, the passage never gets into the issue of whether Columbus Day should still be celebrated. If arguing this were really the primary purpose of the passage, then the author would have made his opinion clear.

Choice (D) is wrong because although the passage mentions that the Vikings’ journey was easier than Columbus’s, it does so in a parenthetical, and this is the only comparison in the entire passage involving the difficulty of the respective journeys. A concern brought up only once isn’t likely to be the primary purpose of a passage.

A. very nearly inevitable. The first sentence of the passage ends by calling the transformation of the Republican Party from an abolitionist organization to a pro-business party “predictable and more-or-less instantaneous.” The rest of the passage offers an explanation for this appraisal, framing the course of events as the only thing that could realistically have happened — in other words, very nearly inevitable.

Choice (B) is wrong because the opening sentence establishes that the transformation of the Republican Party was not “a long and complex process” (a near-paraphrase of “the surprising result of a long struggle”), despite the fact that “many might understandably assume” it was. As an argumentative passage will often do, this passage opens by explaining what is not the case before going on to explain what is the case.

Choice (C) is wrong because, while the passage explains that the abolitionists who founded the Republican Party “considered their duty done and got out of politics” after the end of slavery, it doesn’t call them naïve and blame them for the party’s subsequent course. This answer choice is too strongly worded — something that should make you suspicious on the actual exam.

Choice (D) is wrong because while the passage does characterize the shift in priorities of the Republican Party as “logical” in the sense that it happened due to a series of identifiable and predictable steps, it does not bring up any “unforeseen circumstances.” On the contrary, the passage explains that northern businessmen did foresee the desirable financial effect that the abolition of slavery would have on their businesses, and that they joined the party specifically for that reason.

Choice (E) is wrong because the passage clearly states that the businessmen who joined the Republican Party wanted there to be “more competition for employment,” so they were hardly trying to reduce such competition.

B. make the best of. The close-in-context adverb awkwardly is a clue to the fact that a troupe playing As You Like It would expect the wrestling-inspired love scene to seem cheesy or even sexist to a modern audience and would therefore have to try and find a way to present the plot device as inoffensively as possible — in other words, to “make the best of” it.

Choice (A) is wrong because there is no indication in the passage that modern troupes are in the habit of actually changing the scene in question. They have to “play it down,” but the passage doesn’t say that they rewrite Shakespeare.

Choice (C) is wrong because, while “draw attention away from” is possibly the best of the wrong answers, it’s not as good as “make the best of.” Why not? Drawing attention away from the plot point in question would be a form of making the best of it — so if Choice (C) is right, then so is Choice B, but only one answer choice can be right. Conversely, Choice (B) can be right on its own, because Choice (C) goes too far. There’s no real way to “draw attention away from” a scene in a play. You can, however, make decisions about different ways of staging it — so “make the best of” works, but “draw attention away from” goes too far.

Choice (D) is wrong because the passage never implies that modern troupes “apologize for” the wrestling plot point in As You Like It. It is implied that they have to stage it cautiously and creatively, but “apologize for” is too extreme.

Choice (E) is wrong because, while “rush through safely” can be a good synonymous phrase for negotiate in other contexts — one might speak of negotiating hurdles or river rapids, for example — it doesn’t fit here.

C. A tricky question is analyzed for a general audience. At the very least, the passage definitely implies that the question of which bands count as “punk” bands is tricky — it does hardly anything aside from explain why the question is difficult to answer. And the passage does definitely appear to have been written for a general audience. Because these things are all that Choice C asserts to be true of the passage, there’s really no way it can be wrong.

Choice (A) is wrong because the passage never implies that there are precisely two sides to the debate about punk rock. On the contrary, the passage gives the impression that there are as many opinions as there are people involved in the discussion! Additionally, the passage never really “suggests a compromise.” It summarizes what others have said, but the author never offers an argument of his own.

Choice (B) is wrong because the passage never says anything along the lines of “many people think that such-and-such is true, but it’s not, and here is what’s true instead.” It summarizes points that many music critics and fans have made, but it never says anything about who is wrong or who is right.

Choice (D) is wrong because the passage never makes any comparisons.

Choice (E) is wrong because, while the passage certainly characterizes “punk” as “a problematic term,” it never goes so far as to suggest that it is meaningless. The idea of the passage seems to be that the term does mean something, but that people can’t agree on what.

E. melancholy philosophizing. The author is certainly philosophizing — in other words, he is tossing out analyses and characterizations of a particular concept (aging). And it seems inarguable that he is melancholy — that is, mournful and blue. Because those two things are all that Choice (E) asserts, and they’re both true, there’s no way that Choice (E) can be wrong.

Choice (A) is wrong because the passage is not really nostalgic — the author is talking more about a present that he isn’t enjoying than about a past that he did enjoy. And he certainly isn’t being self-justifying. If anything, he is beating up on himself, which is exactly the opposite.

Choice (B) is wrong because the author seems more sad than annoyed. He doesn’t like what he’s talking about, but it’s making him depressed, not angry. And he isn’t being defensive about anything. He’s admitting his faults rather than making excuses for them.

Choice (C) is wrong because while the author is hypothesizing — in other words, coming up with possible explanations for a phenomenon — nothing in the passage suggests that he’s paranoid. The author is feeling blue about getting older, not freaking out because he thinks people are out to get him.

Choice (D) is wrong because the author seems much more sad than he does blissful. And as for ignorance, it seems as though he is only too aware of his problems, not oblivious to them.

B. the fact that reading is popular enough among the masses for bad books to be outselling good ones. In context, the author says that the “cause for celebration” is the “reason behind” the fact that “serious” books “are no longer the most famous books.” He then explains that this is because certain “classes of people” (that is, the masses) who once would not have read at all are now reading frequently. The result is that bad books outsell good ones, but the way the author sees it, this is better than back when most people didn’t read at all.

Choice (A) is wrong because, although the author puts words like “good” and “serious” in quotes to acknowledge the fact that such distinctions about literature are subjective, there is no indication that the author doesn’t think there is actually such a thing as the distinction between good and bad books. He is being politic and self-effacing about it, but the author does, in fact, appear to believe that some books really are better than others.

Choice (C) is wrong because although the author definitely does say that more young people are reading without being forced to and that this is a good thing, this particular fact is not the specific “cause for celebration” that the question asks about. The author uses the phrase “cause for celebration” earlier in the passage, about something else.

Choice (D) is wrong because, though he’s trying to be as nice as possible about it, the author does, in fact, appear to think that Twilight and The DaVinci Code are not exactly the greatest books in the world. After all, the assertion that some books (like popular bestsellers) are not as good as others (like serious literature) is necessary for the author to make his point. If he didn’t think this was the case, then he wouldn’t have written the passage.

Choice (E) is wrong because the passage doesn’t argue that the masses are only reading because of social pressure. Nothing about societal pressure is mentioned or alluded to in the passage.

Writing answers and explanations

Use this answer key to score the practice writing questions in this chapter. The answer explanations give you some insight as to why the correct answer is better than the other choices.

B. you, you. This section of the sentence contains a comma splice.

Choice (A) is wrong because this imperative clause is properly constructed. Choice (C) is wrong because no comma before the because clause is necessary, and the correct spelling of it’s is used.

Choice (D) is wrong because the correct preposition is used, and affection is spelled correctly. Choice (E) is wrong because there is in fact an error in the sentence.

D. to which. The speaker is talking about a human being, and the pronoun is the object of a preposition, so it should be whom instead of which.

Choice (A) is wrong because the normal past tense is correct here. Choice (B) is wrong because the comma correctly joins an initial subordinate when clause and a subsequent independent clause.

Choice (C) is wrong because that is the appropriate relative pronoun for an essential clause. Choice (E) is wrong because there is in fact an error in the sentence.

A. You’re computer. The possessive pronoun is spelled your, and that’s the one you need here (you’re means “you are”).

Choice (B) is wrong because a comma after a conjunction is correct in the rare instances where an appositive clause immediately follows the conjunction. Choice (C) is wrong because the comma here correctly marks the end of the appositive clause and the beginning of the final independent clause.

Choice (D) is wrong because data is plural. Choice (E) is wrong because there is in fact an error in this sentence.

E. No error. There is no error in this sentence.

Choice (A) is wrong because this is the correct spelling of it’s in this context (the one that means “it is”). Choice (B) is wrong because a comma is necessary here, as an appositive clause interrupts the subordinate that clause.

Choice (C) is wrong because, although many people would say “taller than him,” it is actually correct to say “taller than he” because than is not a preposition. Choice (D) is wrong because the infinitive form of the verb (“to win”) is correct in this context.

C. Coulrophobia, the fear of clowns, is a phenomenon more widespread than many realize. This sentence correctly presents a single independent clause that is interrupted by an appositive clause set off with a pair of commas.

Choice (A) is wrong because a comma before the conjunction is incorrect here, as an independent clause does not follow it. Choice (B) is wrong because the comma and it after the subject of the sentence is unnecessary, and the spelling should be than instead of then.

Choice (D) is wrong because the sentence has no main verb, and the spelling should be than instead of then. Choice (E) is wrong because this sentence contains a comma splice.

E. The octopus is a surprisingly smart animal: It can solve mazes amazingly skillfully. Both independent clauses are correctly constructed, and a colon is an acceptable way (though not the only way) of joining them.

Choice (A) is wrong because the sentence contains a comma splice, the subject and pronoun do not agree in terms of number, and you need the adverb amazingly rather than the adjective amazing. Choice (B) is wrong because a comma is not needed before the that clause and because the adjectives amazing and skillful appear to modify the noun mazes, when you want them to be adverbs (amazingly and skillfully) modifying the verb solve.

Choice (C) is wrong because the sentence contains a comma splice, and because you want the adverb skillfully rather than the adjective skillful. Choice (D) is wrong because the semicolon does not join two independent clauses (a which clause is not an independent clause).

A. Although it was believed for years that they weren’t, biologists have recently proven that pandas are in fact true bears. The sentence correctly presents an independent clause preceded by a subordinate although clause and a comma, and it doesn’t incorrectly capitalize the names of animals.

Choice (B) is wrong because it is incorrect to include both although and but (you need one or the other, but not both), and because Pandas should not be capitalized. Choice (C) is wrong because Pandas and Bears should not be capitalized.

Choice (D) is wrong because however should be used to interrupt a single independent clause, not join two of them, and because Pandas should not be capitalized. Choice (E) is wrong because this sentence contains a comma splice.

B. Whoever parked the car that is in the driveway could have done a better job. The subjective case whoever is correctly used for the subject of the sentence, the essential that clause is not set off with any commas, and the correct could have is used in place of the incorrect could of.

Choice (A) is wrong because whoever, rather than whomever, should be used for the subject of the sentence, a that clause should not be set off with commas, and could have is correct, not could of. Choice (C) is wrong because no comma is needed, and because could have is correct, not could of.

Choice (D) is wrong because whoever, rather than whomever, should be used for the subject of the sentence, and because a which clause would need to be set off with commas. Choice (E) is wrong because whoever, rather than whomever, should be used for the subject of the sentence.

Math answers and explanations

Use this answer key to score the practice mathematics questions in this chapter.

- E. 2010. The year 2010 yielded the highest bicycle sales of $230,000.

- B. 2007–2008. Bicycle sales changed the most between the years 2007–2008. The change was $70,000.

- D. 187,500. The average sales are found by adding the total sales for all years and dividing the total by the number of years:

.

. - C. 215,000. Put the sales in order from least to greatest:

Cross out the numbers alternating between one on the left and one on the right until you reach the numbers in the middle of the data set. There are two numbers in the center; take the average of them and you have the median:

- A. 50–59. The stem of 5 indicates that six people scored in the interval of 50–59 with the scores of 50, 50, 55, 55, 55, 59.

- C. 70. Extract the data from the stem-and-leaf plot and highlight the middle number:

- A. 85. The score that occurs the most often is 85, so 85 is the mode.

- A. 46 percent. Fifty people were surveyed regarding their favorite foods.

or 46 percent liked pizza;

or 46 percent liked pizza;  or 40 percent liked hamburgers;

or 40 percent liked hamburgers;  or 10 percent liked pizza and hamburgers;

or 10 percent liked pizza and hamburgers;  or 4 percent did not like either.

or 4 percent did not like either. - E. 4 percent. Fifty people were surveyed regarding their favorite foods.

or 46 percent liked pizza;

or 46 percent liked pizza;  or 40 percent liked hamburgers;

or 40 percent liked hamburgers;  or 10 percent liked pizza and hamburgers;

or 10 percent liked pizza and hamburgers;  or 4 percent did not like either.

or 4 percent did not like either. - D. 2:3. The ratio of wins to total games played is 8:12. Set up the ratio of wins to total games played and reduce your answer by dividing both numbers by 4.

- C. $1.40. Set up a proportion to compare the cost for 5 pounds of apples to the cost for 2 pounds of apples. Cross multiply to find that 2 pounds of apples cost $1.40.

- A. Cassie earns $15 each day she works plus a flat rate of $50 per month. What is m, the total amount she earns in a month when she works d number of days? The amount for m is the total Cassie earns each day she works at a rate of $15 per day, plus a flat rate of $50.

- C. 2/5. There are 25 counters in the bag; 10 out of 25 are yellow, or 2/5 when simplified.

- A. 2/5. There are six prime numbers from 1 to 15: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13. This is 6/15, which is 2/5 when simplified.

- B.

. 0.000000000753 when written in scientific notation is

. 0.000000000753 when written in scientific notation is  . A number written in scientific notation has two parts: The first part is a single digit (a natural number from 1 to 9) followed by a decimal point and one or more other digits. The second part is

. A number written in scientific notation has two parts: The first part is a single digit (a natural number from 1 to 9) followed by a decimal point and one or more other digits. The second part is  raised to a power. The power indicates how many spaces you moved the decimal point to get to the 7 in 7.53, which was 10 times. When the decimal point is moved right, the power is negative.

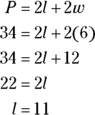

raised to a power. The power indicates how many spaces you moved the decimal point to get to the 7 in 7.53, which was 10 times. When the decimal point is moved right, the power is negative. - D. 11. The perimeter, in this case 34, is the sum of all the sides. You were given the width of 6 in the problem. Using

, you can find the missing side.

, you can find the missing side.

- A. 13. Using the Pythagorean theorem formula

, substitute the value of the legs for a and b and solve for c.

, substitute the value of the legs for a and b and solve for c.

- C. 28. An isosceles triangle has two sides of equal length. Given that the perimeter or distance around the triangle is 62, you can solve for the base.

- D. 9a10. The exponent of 2 on the outside of the parenthesis indicates that you are to raise everything inside the parentheses to the second power.

- B.

. A number written in scientific notation has two parts: The first part is the digit or a number from 1 to 9 (the decimal point must be placed after the first digit). The second part is × 10 raised to a power. The first part of the number in Choice (B) is not a number from 1 to 9.

. A number written in scientific notation has two parts: The first part is the digit or a number from 1 to 9 (the decimal point must be placed after the first digit). The second part is × 10 raised to a power. The first part of the number in Choice (B) is not a number from 1 to 9.

Assessing Your Results

Now that you’ve answered and reviewed a representative sample of Praxis questions, you can evaluate how you did and figure out which subjects you need to spend more time reviewing. Even if you missed a couple of questions, don’t worry. That was the point of answering the assessment questions. You’re still at an early stage in your process of preparation for the Praxis, and there’s a lot of book left to go.

Identifying categories where you struggled

The areas where you struggled the most are the areas you need to focus on the most. To figure out where you struggled, focus on each section of the practice test and outline the areas in which you need the most improvement. Briefly describe everything you missed, and look for patterns. Under each test subject (math, reading, writing), write the names of more specific categories, and then write even more specific categories under those. (Use the table of contents for help identifying specific categories within each test.) You may need to have a subcategory titled “Other.”

For example, the first level of subheadings for math consists of the four major categories of Praxis Core math questions — number and quantity (basic math), algebra and functions, geometry, and statistics and probability. Each of those categories has its own categories (look at the chapters for each of the broad categories to break them down further). Continue to drill down into the topics until you identify the specific area you need to review. What matters is that you organize your weakest areas in a way that you can keep up with them and work on them.

After you’ve identified the categories that gave you trouble, look at the answer choices you picked incorrectly. Compare them to the correct answer choices. Review your mistakes and be sure you understand why any incorrect answers were incorrect. If something is unclear, ask a professor to help you understand where you went wrong (see the next section for more on this).

Taking notes on the areas where you succeeded can also help you. Improving your knowledge and skills concerning those areas can give you an edge for getting difficult questions correct.

Understanding where you went wrong specifically

Along with making an outline of the types of questions you missed, look for reasons for not getting the ones you missed. Did you lack knowledge that you need to review? Did you simply make an error? Did you confuse one idea with another? Did you not use a strategy you could have used that would have made the difference? Make a list of these reasons and keep them in mind as you work on gaining the necessary knowledge and practice as well as the test-taking skills that will help you.

The Praxis Core exam requires critical thinking beyond mere knowledge, but knowledge is extremely important, and so is strategy. The chapters in Parts 2, 3, and 4 review the knowledge you need to know for each topic on the Praxis, and the Parts conclude with a strategy chapter to help you increase your chances of answering a question right when you’re not 100 percent sure of the answer.

However, don’t focus only on how many questions you missed and what types of questions they were. You can improve your future scores by asking yourself right now: What did the wrong answers you picked have in common? After all, if you failed to pick the right answer to a given question, that means you were fooled by one of the wrong answers. Go back over the explanations to the questions you missed, examine the differences between the right answers and the wrong answers that fooled you, and try to develop a sense of what type of wrong answers you tend to be fooled by. Then you’ll know what to watch out for!

When it comes to math questions, you’ll likely have to go back and look at how you worked the problem to identify where you went wrong.

When it comes to the reading and writing questions, think about these questions: Do you tend to jump after the wrong answer with the biggest words in it? Or are you fooled by something that’s probably true in real life, but that the passage never actually mentions? Did they get you with the wrong answer that mentions a detail from the end of the passage because they know it’s fresh in your mind? Do you have a weakness for the wrong answer that uses the greatest number of exact words from the passage?

There’s an old saying among test-prep tutors: “I can tell you how to get a question right, but only you can tell yourself why you got one wrong.” Okay, fine, it’s not an old saying — we just made it up. But it should be an old saying, because it makes a good point.

Focus first on the areas you need to study most. Later you can review the areas you’re more familiar with.

Focus first on the areas you need to study most. Later you can review the areas you’re more familiar with.