CHAPTER 4

Cost Allowability

Knowing what costs can be claimed is essential in preparing price proposals and indirect cost rate proposals, as well as understanding how profit is affected by unallowable costs. In addition, knowing what costs are allowable will aid in avoiding penalties for claiming expressly unallowable costs as well as government allegations of defective pricing, criminal or civil false claims, or fraud.

ORIGIN OF GOVERNMENT CONTRACT COST PRINCIPLES

The first U.S. government purchases were on a firm-fixed-price basis for such items as horses, guns, and cannons. Over the years, the rules and regulations on the allowability of costs under government contracts have evolved from simple directives first developed during World War I into rather complex and substantial rules. The Revenue Act of 1916 contained the first cost principles, which consisted of a mere one page of cost allowability rules. In the late 1930s, the Treasury Department began to issue Treasury Decisions (TDs) regarding cost-type contract costs and profits. TD 5000, which was issued in 1940, contained only about six pages of guidelines on both cost allowability and cost allocability. TD 5000 continued to be used as the basic cost rules until the first Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR) was published in 1949. A major revision of the ASPR was promulgated in 1959. In 1978, the title of the ASPR was changed to the Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR).

The Federal Procurement Regulation (FPR) was developed almost concurrently with the ASPR and the DAR and, for the most part, was modeled after the defense regulations. Civilian (nondefense) agencies used the FPR, although several (e.g., National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Department of Energy) developed their own regulations based either on the ASPR and the DAR or on the FPR.

After several years of study and development, governmentwide acquisition regulations were issued as the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) on April 1, 1984. To accommodate special departmental and agency needs, organizations were authorized to publish supplemental regulations to the FAR. These supplemental regulations could be more stringent than those in the FAR, but they could not contradict or establish as allowable any cost made specifically unallowable by the FAR. In addition to the FAR (and the agencies’ supplemental regulations), promulgations by the Cost Accounting Standards Board (CASB), generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), and federal and state laws all play important roles in determining contract cost allowability.

APPLICABILITY OF GOVERNMENT COST REGULATIONS

All contracts and contract modifications for supplies and services or experimental, developmental, and research work negotiated on the basis of cost with commercial organizations must adhere to the cost principles and procedures set forth in FAR Part 31.2. These cost principles must be used in pricing negotiated supplies, services, research contracts, and contract modifications with commercial organizations whenever the contract or subcontract exceeds $550,000. The cost principles and procedures must be used under the following circumstances:

Determining reimbursable costs under cost-reimbursement contracts, including any cost-reimbursement subcontracts, and the cost-reimbursement portion of T&M contracts

Negotiating overhead rates

Proposing, negotiating, or determining costs under firm-fixed price and cost-reimbursement contracts

Revising fixed-price-incentive contracts

Redetermining prices of prospective and retroactive price redetermination contracts

Pricing changes and other contract modifications.

Cost allowability provisions did not always apply to fixed-price contracts. By 1959, various versions of fixed-price contracts had become more common and the government designated the allowability provisions as “guides” to pricing fixed-price contracts. In July 1970, the regulations were revised to make cost allowability provisions applicable to both fixed-price contracts and cost-type contracts. This aspect was reinforced in a Board of Contract Appeals case involving the Lockheed-Georgia Co. (ASBCA No. 27660), where the Board accepted interest expense as an allowable cost despite the specific cost principle that states that interest expense for financing purposes is unallowable.

The cost allowability rules do not apply to U.S. government contracts awarded to the Canadian governmental agency known as the Canadian Commercial Corporation. This agency was established as a conduit for U.S. government contract awards to commercial organizations in Canada. By agreement between the two nations, such awards will be treated as exempt from cost rules because the awards are to the sovereign Canadian government, which has its own cost regulations.

FAR 31.102 states: “… application of cost principles to fixed-price contracts and subcontracts shall not be construed as a requirement to negotiate agreements on individual elements of cost in arriving at agreement on the total price. The final price accepted by the parties reflects agreement only on the total price. Further, notwithstanding the mandatory use of cost principles, the objective will continue to be to negotiate prices that are fair and reasonable, cost and other factors considered.”

The final price eventually agreed to by the parties reflects agreement only on the total price, not on line-item cost and profit amounts. This FAR provision anticipates disagreement in certain cases between the government and a contractor on the allow-ability and allocability of particular types of costs. Furthermore, this FAR provision recognizes that differences of opinion are certain to arise in interpreting the regulations, including the structure of cost allocation bases and indirect cost pools, as well as the allocation to cost objectives. The FAR focuses on the real objective of negotiating a bottom-line price for the work and not necessarily agreeing on each line item of cost and profit, such as labor, material, or overhead.

In this connection, the contractor may reach a bottom-line price quite differently from the way the government does. For example, the contractor might have a different concept of which cost items are allowable and allocable to the contract, such as certain items of labor and material, overhead, and G&A expenses. In addition, the contractor might believe that it was successful in negotiating 15 percent profit on the work, but the government might believe that it negotiated only a 7 percent profit. Again, the only amount on which there should be no difference of opinion is the bottom-line price incorporated into the contract.

FAR CONCEPT OF TOTAL COST

FAR 31.201-1 discusses total cost: “The total cost of a contract is the sum of the allowable direct and indirect cost allocable to the contract, incurred or to be incurred, less any allocable credits, plus any allocable cost of money pursuant to 31.205-10. In ascertaining what constitutes a cost, any generally accepted method of determining or estimating costs that is equitable and is consistently applied may be used, including standard costs properly adjusted for applicable variances. See 31.201-2(b) and (c) for CAS requirements.”

Thus, the FAR neither requires nor mandates a single accounting system or method of determining total cost. Contractors are free to develop and use the type of accounting system they deem appropriate to reflect the financial results of their operations properly, considering the nature of their services or products. A contractor can still choose many of the accounting techniques to use, including the differentiation of direct and indirect costs, the number and content of overhead cost pools, and the method of allocating overhead costs to cost objectives.

CREDITS

In defining total contract costs as allowable costs less any allocable credits, FAR 31.201-5 recognizes that certain receipts should be credited against the cost to which those items relate, instead of being recorded as revenue. These receipts are not truly revenues from the sale of goods or services but are, in effect, a reduction of the cost of the transactions to which they relate. To treat them as revenues would distort both revenues and cost. The applicable portion of any income, rebate, allowance, or other credit relating to any allowable cost and received by or accruing to the contractor is to be credited to the government either as a cost reduction or by cash refund.

For example, the following receipts should be treated as credits: (1) prompt payment and trade discounts on the cost of materials or services; (2) refunds on materials returned to the vendor; (3) receipts from the sale of scrap; (4) dividends and rebates received under insurance policies; (5) rebates from travel agencies on airline tickets; and (6) entries to correct accounting errors such as overpayments.

If a refund relates to more than one transaction, the credit should be allocated on a pro rata basis to the various transactions to which it belongs. In those cases, the government is entitled to only its pro rata share of the credit. Many times this type of transaction credit is accomplished through an overhead or G&A pool. State and local tax credits can be quite complex as they are usually very location-specific. An analysis of location-specific government contract activity is usually warranted to ensure that: (1) proper credit is forwarded to the government; and (2) the proper amount is credited to the other business of the contractor.

Northrop Corporation is a good example of how the credit rule is applied (ASBCA No. 8502). After the Renegotiation Board reduced the contractor’s profits, the contractor applied to the state of California for a refund of the California franchise tax that it had paid on the basis of profits before renegotiation. When the contractor recovered the excess franchise tax and the interest on it, the government demanded its portion of the refunded franchise tax, with interest, for which the contractor had been reimbursed under its negotiated CPFF contracts. The ASBCA held for the government.

Over the past few years, many ASBCA cases have established case law for determining the division of credits. Companies have been very aggressive in trying to ensure that equity is served in determining credit allocation. Often, the contractor’s commercial business was not receiving the recognition it deserved. Sometimes a facility housed both government and commercial business. As a result, any credits received an enormous amount of scrutiny to determine an equitable distribution.

Another aspect of contracting that affects the distribution of credits is the mix of contracts. A contractor may begin a period of business activity with a large number of fixed-price contracts. During the period, the mix of contracts may shift toward more cost-reimbursable contracts. Credits would have to be scrutinized carefully to ascertain which period they applied to and to what degree government contracts, if any, would have been affected. The problem of contract mix has been a thorny issue in allocating credits.

For instance, a fixed-price contract bid awarded early in the accounting period was not costed/priced to include a credit for taxes that, at the time, was not known would occur. Subsequently, when the credit was issued by the taxing authority, no credit was due to the fixed-price contract. The government can argue to have credit issued. However, if instead of a credit an additional tax had been levied, the fixed-price contract would not have been increased to cover that additional cost. Fixed-price contracts carry a certain sanctity for not having their price adjusted for occurrences, either plus or minus, during contract performance.

INCURRED COSTS

Ordinarily, a cost is incurred when an obligation to pay another party arises. Under accrual accounting, costs come into existence when a liability occurs. This matter is not clear-cut, however. Problems (such as payments without obligation) have resulted in various court actions stemming from the attempt to decide when costs have been incurred for government contract purposes. Sometimes payment may clearly be necessary for contract performance to be considered an incurred cost.

In Wyman-Gordon (ASBCA No. 5100), a contractor lent money to a subcontractor who successfully completed the work but was unable to repay the loan because he went broke. The contracting officer disallowed the loan as a bad debt. The ASBCA disagreed and ruled that the cost was necessary under the circumstances. On the other hand, in Westinghouse Electric Corp., where no payment had actually been made, the ASBCA refused to recognize the prime contractor’s claim for an overrun by the subcontractor.

In Norcoast Constructors Inc. and Morrison-Knudsen (ASBCA. No. 16483), the government took possession of storage tanks the contractor was entitled to keep under the contract. The ASBCA stated that the contractor was due an equitable adjustment amounting to the value of the tanks. Although the government argued that the contractor’s costs were not increased, the ASBCA said that the contractor could have sold the tanks, thus lowering the contract costs.

“Contingent liabilities” have also created some problems. In General Dynamics Corp. (ASBCA No. 8867), the ASBCA did not permit accrued “potential” liabilities related to layoff benefits for employees, since future payments were not certain and no funds had been set aside.

The problem of contingent liability was also present in A.C.F. Brill Motors Co. (ASBCA No. 2470). A subcontractor closed a plant, laying off employees, which raised the state unemployment insurance rate. The subcontractor included as a contract cost the increased payments already made and those to be made in the future. In denying the contractor’s claim, the ASBCA observed that the future payments were contingent on a variety of factors, all of which might not necessarily have been related to the employee layoff issue.

Another area of costs that is challenged is “to be incurred” costs. The government usually expresses skepticism that these costs will ever materialize. However, contractors can quite frequently rely on the incurrence of like costs in past activities. Some examples are: certain recurring taxes, equipment-specific depreciation costs, and in certain instances “compelled” post-retirement cost, including medical and pension expenses. In cases of plant closures, for instance, many potential areas of cost must be recognized. These could include items such as severance pay, unpaid taxes, environmental impact costs, and underfunded pension plans. Conversely, over-funded pension plans have created havoc in attempting to close a plant segment.

The “paid cost” rule is another area that was briefly applied and then rescinded. While this rule was in effect, a cost for a product or service performed by a vendor or subcontractor had to be paid before it could be claimed by a prime contractor. Small businesses did not have this requirement. In 2000, this rule was deleted from the regulations. This permits payment when a contractor is not delinquent in paying costs of contract performance in the ordinary course of business. This would allow a cost to be recognized (and thus subsequently billed to the government) when it was entered on the books of a company as an “unaudited liability.” In other words, if a shipment or an invoice had been received, and not yet paid, there would be recognition of a liability that would have to be met in a future period.

ALLOWABILITY OF COSTS

FAR Subsection 31.201-2 states that the factors to be considered in determining whether a cost is allowable include the following:

Reasonableness

Allocability

Standards promulgated by the CAS Board, if applicable; otherwise, generally accepted accounting principles and practices appropriate to the particular circumstances

Terms of the contract

Any limitations set forth in FAR 31.2.

Although a particular cost meets these criteria, another aspect sometimes determines cost allowability: perception. Perception has nothing to do with true allowability. A case in point involves costs for kenneling a dog. During the congressional hearings in the 1980s, the Washington Post ran an article about how taxpayers were paying the cost of kenneling a dog owned by an aerospace executive. Although the costs were allowable, there was an appearance of impropriety. Needless to say, from that time on, government contractors have had to view virtually every cost not only from the aspect of cost allowability but also from the aspect of “front page perception.”

To the extent that a contractor’s costs are subject to the CAS and a method of cost allocation is inconsistent with the standard(s), that method is unacceptable and must be altered to conform to the standard. However, if the CASB has not issued a standard on a particular matter and the cost is not deemed “unallowable” per the FAR, a contractor may apply GAAP to its cost accounting system to account for the cost. Note that not all CASB promulgations are included in the FAR allow-ablity criteria: Only the CAS standards are included; CAS rules and regulations (such as those related to cost impact statements and accounting changes) are not included.

Although GAAP is noted as an alternative, it is rarely used for determining allowability. Usually, as soon as GAAP is used to determine allowability, the government rule makers amend the FAR to make such costs specifically unallowable. An outstanding example is a case involving Gould Co. (ASBCA No. 24881) accounting for goodwill costs. The Board ruled that goodwill was allowable in writing up assets. The government changed the FAR to make goodwill unallowable as quickly as it could. In another instance, stock purchase agreements governed by IRS rules were determined by case law to be allowable. Once again, the FAR was amended to make these costs unallowable.

It is important to recognize that all allowability criteria must be met for a cost to be allowable. For example, if a cost complies with the CAS or GAAP but not with the FAR, the cost is unallowable. Furthermore, even if a cost is in compliance with the CAS, with GAAP, and with the FAR, the government could still negotiate a contract clause that would restrict reimbursement of that cost.

For questions of allocability, the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals has ruled that a conflict between a CAS and a specific FAR principle should be decided in favor of the terms of the CAS, because the purpose of the CAS was to establish cost allocability (Boeing Corp., ASBCA No. 28342). However, in another case (Emerson Electric, ASBCA No. 30090), the Board ruled that where the CAS permit several accounting choices, the FAR can effectively limit those choices to a single alternative. In these cases, no conflict exists, because the FAR-dictated choice complies with both the CAS and the FAR.

A court decision involving General Electric Co. (US Cls Ct No. 25492) adds confusion to any attempt to separate the concepts of allowability and allocability. In this case, the focus was on the terminology of the 1979-1985 Defense Acquisition Regulation and the FAR provision on foreign selling expenses. During this period, the regulation terms these expenses unallocable. In 1985, the regulation was revised to recognize that the correct term should have been “unallowable.” In deciding this case, the court ignored this revision and took the position that the term “allowability” was understood to be the applicable term despite the actual wording in the regulation.

In reversing the Martin decision (ASBCA No. 35895) on the allowability of G&A expenses that are applied to an unallowable G&A base, the U.S. Court of Appeals stated essentially that any FAR provision by its nature relates to cost allowability rather than allocability. Thus, no matter how the allowability criteria are expressed in the FAR (i.e., even if allowability is in terms of allocability), no conflict exists because the FAR has jurisdiction over allowability issues.

One of the specific functions of the reestablished CAS Board (1989) is to resolve inconsistencies between the CAS and the FAR. The administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) is directed to resolve these inconsistencies. If an inconsistency is not resolved, the regulation that is inconsistent with the CAS may be ignored.

Government agencies are permitted to publish supplemental regulations to meet their special needs. These rules may add allow-ability criteria to the FAR criteria but cannot render allowable any cost made specifically unallowable by the FAR. Federal departments and agencies that have published regulations include Agriculture, the Agency for International Development, Commerce, Defense, Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the General Services Administration, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Small Business Administration, Transportation, Treasury, and the Veteran Administration. The Air Force, Air Force Systems Command, Army, and Navy have published regulations along with the Department of Defense. Agency regulations have significantly modified the FAR on the allowability of independent research and development (IR&D), bid and proposal (B&P), and precontract costs.

Reasonableness

What is reasonable? Why is the government interested in controlling costs on this basis? How is reasonableness applied to contractors in a complex business world? These valid questions have no easy answers. Obviously, the government is concerned about protecting its interests and ensuring that work is done in an efficient and economical manner. The factor of reasonableness is often the government’s entrée to cost recovery as well as to an evaluation of areas that are essentially limited to management prerogative. Needless to say, this area often involves controversy.

Any determination of reasonableness must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. This precept is illustrated in Bruce Construction Corporation (324 F.2d 516). The court stated that reasonableness should be determined by evaluating the circumstances at the time the cost was incurred, rather than by applying any universal principle. The court also noted that where a cost has already been incurred, a presumption of reasonableness may apply. Congressional direction shifted this burden of proof regarding reasonableness from the government to the contractor.

An expense may be disallowed as unreasonable in “amount.” This area involves complicated issues and interpretations. Several different factors may come into play, including relative amount, public policy, custom, and usage. In Stanley Aviation Corporation (ASBCA No. 12292), the government alleged that the contractor’s indirect rates were far in excess of estimated amounts and challenged the costs on the basis of reasonableness. The ASBCA disagreed and said that the government should have examined the underlying circumstances in more detail, including an evaluation of the indirect cost pools on an item-by-item basis. Furthermore, the court recognized that the contractor was acting under the strongest possible economic motivation to reduce its costs.

In the determination of reasonableness, everything is relative. Cost comparisons involving the same items under similar circumstances are important in justifying a reasonable amount. A key case that illustrates this concept is Lulejian and Association, Inc. (ASBCA No. 20094). In this case, the government attempted to make cost comparisons of items involving the contractor’s compensation, but the ASBCA rejected the comparisons as insufficient because: (1) they involved years different from the one at issue; (2) they were incurred by organizations of a different type from the contractor’s; and (3) they involved services of lesser duty and responsibility than those at issue. In ruling for the contractor, the ASBCA stated that “… the overall cost was reasonable compared to the cost of such benefits in the industry in general, and the cost of its relatively liberal pension plan and group life insurance plan was offset by the absence of other benefits commonly available to employees in the industry.”

The reasonableness of specific costs must be examined closely in firms or divisions not subject to effective competitive restraints. What is reasonable depends on a variety of considerations and circumstances involving both the nature and the amount of the cost in question. In determining the reasonableness of a specific cost, the contracting officer is to consider:

Whether it is the type of cost generally recognized as ordinary and necessary for the conduct of the contractor’s business or the contract performance

Generally accepted sound business practices, arm’s-length bargaining, and federal and state laws and regulations

The contractor’s responsibilities to the government, other customers, the owners of the business, employees, and the public at large

Any significant deviations from the contractor’s established practices.

Ordinary and Necessary

In a commercial setting, a cost that is ordinary for the conduct of a business or necessary to advance performance on a contract may be presumed to be reasonable. Other considerations come into play when contracting with the government. The terms “ordinary” and “necessary” are not defined precisely in the FAR. Therefore, they are somewhat open to interpretation. Contracting officers often attempt to define what is ordinary and necessary by establishing contract ceilings on particular direct or indirect costs. For example, they often establish limits on travel costs, fringe benefits, and escalation rates. Government auditors also play a key role in determining what is ordinary and necessary. They may question the cost associated with using a private plane or conducting periodic management meetings at distant, exotic locations as unnecessary and out of the ordinary. Any determination of this kind should consider a number of factors, including the contractor’s size versus relative cost of the questioned item, type of business, industry custom, and reasonable alternatives.

In Vare Industries, Inc. (ASBCA 12126, et al.), for example, the contractor was using a senior engineer to complete contract closeout functions. The government alleged that the labor involved was unreasonable because it was not ordinary for an engineer and could effectively be accomplished by a clerk. The ASBCA upheld the government’s charge that this was an unreasonable cost. The contractor was also incurring a certain amount of cost associated with providing security to protect two huts at the contract work site. The government alleged that the costs were unreasonable, because the contract did not call for any such security measures and there was nothing extraordinary about the huts or their contents that would make such a cost necessary. The ASBCA, once again, agreed with the government.

Accepted Business Practices

Businesses operating in a competitive environment try to be cost-effective to maximize profits. Generally, if there is competition, the resulting increases paid are reasonable. The constraint on costs imposed by arm’s-length bargaining can be troublesome. In particular, the government often questions dealings a contractor has with organizations that are related through common management or common ownership. The critical element is the extent of common control. Unfortunately, guidelines for determining this are not precise and have been established largely as the result of BCA decisions. Normally, an interest of 50 percent or more would be necessary to establish common control. However, as a practical matter, less than 50 percent ownership is needed to gain control if the remaining stock or ownership interest is dispersed among many owners.

In Brown Engineering Company (NASA BCA No. 31), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Board of Contract Appeals (NASA BCA) concluded that common ownership of as little as 37 percent could result in a controlling interest. The NASA BCA was influenced by the fact that the two entities had a number of common directors and business facilities. Moreover, one entity owned all the stock of the other, and the actual nature of their business transactions implied common control.

In A.S. Thomas, Inc. (ASBCA No. 10745), however, the ASBCA found that common control did not exist even though one individual owned one of the firms outright and about 43 percent of the other company’s stock. In Data Design Labs (ASBCA No. 26753), several executives of a publicly held contractor formed a leasing company to build office space and then lease it to the contractor. The same executives actually signed the lease on behalf of both the lessee contractor and the newly formed lessor company (although the lease had been approved in advance by the contractor’s board of directors). The ASBCA held that, because of the approval of the lease by the contractor’s board of directors and because the owners of the leasing company held less than 10 percent of the contractor’s stock, no common control existed. The facts and circumstances of each case, in other words, determine whether common control exists.

If it is determined that common control exists, transfers of goods and services must be made at cost. This rule was established to avoid the pyramiding of profits that would be possible if profits were allowed on intra-company transfers. This issue is particularly critical for organizations that lease or rent buildings or equipment from related companies. Interorganizational transfers between such firms at other than cost, however, can be made under special circumstances.

Prudent Business Person

This criterion requires that management consider its responsibilities to the business owners, employees, customers, the government, and the public at large. Actions that may seem advantageous to employees may be at direct odds with responsibilities to shareholders, the government, and the public. For example, in the case of Digital Simulation Systems, Inc. (NASA BCA No. 975-8), the BCA stated that “the government properly disallowed a cost-plus-fixed-fee con-trac-tor’s contribution to its employee’s profit-sharing plan because the contractor’s request for profit shares in excess of its net profits was unreasonable.” Under the profit-sharing plan, the contractor was increasing the compensation paid to its officers beyond a reasonable profit level. The ASBCA noted that the owners of a business normally expect a return on their investment, and the contractor’s method of distributing profits beyond the level of “net” profits was operating to deny such a return.

Significant Deviations

Any significant deviation from a contractor’s established policies and practices will be examined closely by the government to determine if this action results in the incurrence of unallowable costs. Costs incurred through consistent application of contractor policies and procedures are more likely to be considered reasonable. Significant deviations raise government concerns regarding the allow-ability of costs. For example, in ARO, Inc. (ASBCA. 13623), a contractor granted several employees leave to participate in a golf tournament. The ASBCA ruled that the additional time off was contrary to the contractor’s established practice and, therefore, the associated costs were unreasonable.

In comparison, in General Dynamics Electric Boat (ASBCA No. 18503), the government alleged that the contractor’s B&P expenses were unreasonable because they differed significantly from B&P expenses in previous years. However, in ruling for the company, the ASBCA recognized that the significant difference in cost was reasonable given the contractor’s declining government sales and resulting efforts to increase business.

Allocability

FAR 31.201-4 establishes the general criteria for determining cost allocability. A cost is allocable if it is assignable or chargeable to one or more cost objectives on the basis of relative benefits received or another equitable relationship. A cost is allocable to a government contract if it: (1) is incurred specifically for the contract; (2) benefits both the contract and other work, and can be distributed to them in reasonable relationship to the benefits received; or (3) is necessary to the overall operation of the business, although a direct relationship to any particular cost objective cannot be shown.

One of the underlying concepts of allocability is that of “full absorption.” Full absorption refers to the allocation of all costs, variable and fixed, to final cost objectives. In contrast, “direct” or “marginal” costing methods apply only variable costs and treat fixed costs as period or sunk costs. This latter approach can be advantageous to management in controlling costs and in making decisions since only the variable costs are considered relevant. Notwithstanding this approach, only full absorption costing may be applied to the pricing and costing of government contracts.

The single most important body of knowledge relating to the allocation issues in government contract costing is the promulgations of the CASB. Because the various government regulations only provide an overview of allocation principles, allocability issues for contracts covered by the CAS are evaluated almost exclusively by the standards. The FAR recognizes and incorporates many of the standards. Even contractors that do not have any CAS-covered contracts feel the influence of the standards because government auditors frequently base their opinions regarding allocability issues on CAS concepts. (See Chapter 6 for further discussion of the CAS.)

Several Claims Court decisions and BCA cases have significantly influenced the development and application of the concept of allocability. These cases illustrate the basic arguments about allocability that often arise.

The proper allocation of costs that benefit several cost objectives has been the subject of a number of cases. In many of them, the government has attempted to establish that no government contracts benefited from, for example, marketing costs. Generally, decisions have held that identification of specific benefits is not necessary; it is sufficient to show that government contracts as a class benefit from the expense in question.

This was the finding in the ASBCA case involving Federal Electric Corporation (ASBCA No. 11324). Also, if the necessity of a cost for the overall operation of a business can be established, then this fact alone usually provides sufficient justification for allocating the cost to government contracts. Patent costs were an example of this in a case involving TRW, Inc. (ASBCA No. 11499) decided by the ASBCA. Another case on costs that benefit the overall business involved General Dynamics Corporation (ASBCA No. 18503). In this case, the government objected to the company’s allocation of commercial bid and proposal costs to government contracts, but the ASBCA allowed the allocations, holding that successful commercial bids would increase the overall business base and thus decrease the allocation of fixed expenses to government contracts. The government has also disputed the allocation of home office expenses.

In KMS Fusion, Inc. (24 CtCl 582), involving lobbying costs, which was decided before the specific cost principle that disallowed these costs, a contractor had maintained a Washington, D.C., office to keep in contact with government officials concerning programs of interest to the company, which was located in the midwest. The Claims Court ruled that benefits arising from a potential increase in business are sufficient to establish allocability of the cost, while observing that the whole government benefits, because the same cost base supports more productive activity.

Cases have clearly established that, even when GAAP addresses an issue that is disputed (though usually it does not), the specific contract’s applicable provisions and government regulations will prevail. When one contractor contended, for example, that the appropriate allocation of a state tax refund was to the year in which the credit became available, the government claimed that the credit should instead be allocated to the year giving rise to the credit. Although the ASBCA acknowledged that the contractor’s treatment of the credit was in accordance with GAAP, it concluded that compliance with GAAP was not the determining factor, since one of the clauses in the contract required the contractor to allocate the refund to the year in which the expense giving rise to the credit was originally incurred.

Costs Incurred Specifically for the Contract

A cost incurred specifically for the contract is usually a “direct cost.” Direct costs normally include such items as direct labor, materials, and subcontracts. As defined by the FAR, a direct cost is “any cost that can be identified specifically with a cost objective.”

Contractors have significant discretion in defining direct and indirect costs. In accordance with the CAS, contractors establish their definition of direct and indirect costs in the form of written policies and procedures and must apply them in a consistent manner. If a contractor does not have CAS-covered contracts, it should establish the same type of policies and procedures.

Both the FAR and the CAS require that: “No final cost objective shall have allocated to it as a direct cost any cost, if other costs incurred for the same purpose in like circumstances have been included in any indirect cost pool to be allocated to that or any other final cost objective. Costs identified specifically with the contract are direct costs of the contract and are to be charged directly to the contract. All costs specifically identified with other final cost objectives of the contractor are direct costs of those cost objectives and are not to be charged to the contract directly or indirectly.”

For reasons of practicality, any direct cost of minor dollar amount may be treated as an indirect cost if the accounting treatment: (1) is consistently applied to all final cost objectives; and (2) produces substantially the same results as treating the cost as a direct cost.

Blanket costs are costs that are identifiable to cost objectives but are so numerous and minor in amount that such identification is impractical. For example, a blanket cost could be the supervision time used during a production process. This cost could be accumulated and for practical purposes be an “allocated” direct cost based on direct labor hours or dollars of the employees supervised.

Costs can only be treated as both direct and indirect if the costs are incurred for different purposes in different circumstances. An example is a contractor who incurs costs for fire fighting under two sets of conditions. One group of fire fighters is for general plant fire protection and another special group of fire fighters is for providing a 24-hour-a-day watch on inflammable material. The latter group has no responsibility for overall plant fire protection. This example illustrates costs incurred under “unlike circumstances.”

Costs Benefiting Several Cost Objectives

FAR 31.203 defines an indirect cost as “any cost not directly identified with a single, final cost objective, but identified with two or more final cost objectives or an intermediate cost objective. It is not subject to treatment as a direct cost. After direct costs have been determined and charged directly to the contract or other work, indirect costs are those remaining to be allocated to the several cost objectives. An indirect cost shall not be allocated to a final cost objective if other costs incurred for the same purpose in like circumstances have been included as a direct cost of that or any other final cost objective.”

The FAR further states that “indirect costs shall be accumulated by logical cost groupings with due consideration of the reasons for incurring such costs.” Such costs are to be assigned on the basis of the relative benefits accruing to the several cost objectives. The government generally prefers the benefits-received criterion over other comparative factors (i.e., causal relationships generated by the base costs) because it considers benefits received to be more equitable and easier to administer. For example, if a government contract causes the contractor to build a fence around its facility, the cost is considered by the government to benefit the entire operation due to decreased employee pilferage, etc. Thus, the cost should be allocated to all work benefiting from the expenditure rather than just the work that actually caused the expenditure. Commonly, manufacturing overhead, selling expenses, and G&A expenses are grouped separately and allocated over different bases.

The accumulation and allocation of manufacturing costs based on beneficial/causal relationships is illustrated in the case of Ellis Machine Works (ASBCA No. 16135). In this case, the contractor wanted to allocate its manufacturing overhead over a base consisting of total labor and material costs.

The ASBCA stated that, given the wide variance in the amount of labor required on jobs having the same amount of total labor and material costs, “direct manufacturing labor is a more accurate measure of the extent of the use of the manufacturing plant.” The ASBCA stated, in part, that the pertinent regulation “… states that a cost is allocable to a particular cost objective in accordance with the relative benefits received or other equitable relationship. A manufacturer’s pool of manufacturing related overhead consists of those costs involved in owning and maintaining its manufacturing plant (buildings and machinery), such as taxes, depreciation, fire insurance, and maintenance. It also includes indirect expenses related to manufacturing labor, such as payroll taxes and insurance, vacations, welfare, pensions and other fringe benefits. Manufacturing overhead, which is the indirect expense of the manufacturing plant, should be allocated to the jobs that generate the need for the manufacturing plant and benefit from its use in the plant that each job generates the cost of and benefits from the manufacturing plant. It is obvious that a job which requires 1,000 hours of manufacturing labor benefits more from the manufacturing plant and should bear a larger share of the manufacturing overhead than another job involving the same labor and material costs which requires only 100 hour of manufacturing labor.”

Indirect cost pools are allocated either to other cost pools (intermediate cost objectives) or to final cost objectives (contracts). Sometimes the functions in a cost pool benefit only other cost pools. For example, occupancy costs could be allocated among cost pools on the basis of a facility measure, such as square footage. Intermediate cost pools are often treated as service centers. For example, computer, word processing, and relocation costs are often grouped in a service center pool and allocated on the basis of a resource usage measurement, such as associated equipment time by project. Costs in this category could ultimately be charged as other direct costs as well as indirect costs. For example, the cost of computer services may be charged to an indirect pool for work done in generating accounting records, whereas it will be charged as an other direct cost for output associated with a contract. No inconsistency in allocating costs is occurring here because the “circumstances” are not alike.

Finally, indirect cost pools might be allocated only to final cost objectives. Indirect costs associated with this category are generally grouped into manufacturing, engineering, and material overhead pools. Allocation of the costs is commonly over such bases as direct labor dollars or hours or materialdollars.

Costs Necessary to the Overall Operation of the Business

The FAR recognizes that this category of expenses cannot be allocated to cost objectives on any base reflecting cause or benefit but is allocable because it benefits the organization as a whole. The most common kinds of expenses in this category are general administration, marketing and sales, and legal and accounting. Because of the nature of these expenses, they must be allocated over a base representing the total activity of the business.

For CAS-covered contracts, CAS 410 requires such a base and provides three alternatives for allocation: (1) total cost input; (2) value-added (i.e., total cost input less materials and subcontracts); or (3) single-element (e.g., direct labor dollars). For modified CAS-covered contracts or non-CAS-covered contracts, as a practical matter, the choice of a total activity base should represent the cost input features of the CAS because government auditors will be applying these concepts in their evaluation of any G&A rate structure. Prior to CAS 410, contractors often used such activities as cost of goods sold or cost of sales as a representation of total activity. CAS 410 does not allow these methods and government auditors object to them as not being a true measure of total activity during a cost accounting period.

One of the more significant of the government’s concerns in evaluating cost allocation relating to G&A expenses is the association of costs with commercial—that is, nongovernment—cost objectives. The allocation of selling and marketing expenses is a common area of controversy between government auditors and contractors.

Contract Terms/Advance Agreements

Contracting officers often use contract clauses to limit reimbursable costs. This can pose a problem, because improperly worded contract clauses (or contract clauses accepted carelessly) can lead to inequitable results. For example, a contract clause may not permit local travel mileage as a direct contract cost. If, however, the contractor’s accounting system treats directly identifiable travel costs as direct costs that benefit specific cost objectives, the effect of such a clause is to make local mileage unallowable for contracts containing this clause. The unallowed costs would, nonetheless, have to be charged to specific contracts (even though they would not be reimbursed on a contract with this clause) and could not be treated as indirect costs. Contractors often assume that, under circumstances such as these, the unallowed costs could be charged to indirect cost pools. However, to be consistent with disclosed or established accounting practices, this cannot be done.

Contract clauses cannot be used to authorize or validate allocations that would conflict with cost principles in the CAS or the FAR. For example, assume that a contracting officer objects to the allocation of G&A to subcontracts on a contract requiring a large number of subcontracts. If the contractor’s accounting system uses total cost input as the allocation base, the acceptance of a contract clause that limited the allocation of G&A only to costs not associated with subcontracts would result in noncompliance with both CAS and FAR consistency requirements (especially CAS 410). Consistency would require the contractor to allocate G&A based on total cost inputs, but because of the clause, the G&A thus allocated to this contract based on the subcontract costs could not be reimbursed. In fact, the government would be inconsistent in requiring a clause forbidding G&A allocations to subcontract costs in this case, because if total cost input is the most equitable allocation base, total cost input should be used as the allocation base for every contract. The G&A allocated as a result should, therefore, always be reimbursed by the government.

Contract clauses that establish ceilings on indirect cost rates are often included in cost-type contracts. Although allowable costs are by definition reimbursable, clauses of this type make indirect costs in excess of the ceiling unallowable even though they would otherwise be properly allocable and allowable. The government believes that such clauses protect it from unexpected or “unreasonable” increases in indirect cost rates. Often, the existence of a sound budgeting and cost control system will convince the government that this clause is not necessary.

Other clauses may provide for postaward reviews (for the purposes of downward price adjustments only) of labor rates under time-and-materials, labor-hour, or fixed-price contracts. This type of clause produces a one-sided arrangement that should be avoided if at all possible. Often only a strong overall negotiating position can prevent the government’s imposition of these contract clauses on a contractor.

FAR 31.109 encourages making advance agreements on the allowability of costs, particularly related to the reasonableness or allocability of costs, in an effort to avoid subsequent disputes. These advance agreements are not required, however, and the lack of an agreement does not create a presumption of unallowability either way. Advance agreements may be negotiated either before or during a contract’s performance but should, in any case, be negotiated before the cost is incurred. The agreements between the government and the contractor must be in writing. Advance agreements may not be made to allow costs that would otherwise be unallowable under the FAR.

The FAR provides several examples of costs for which advance agreements may be particularly helpful, including: compensation for personal services; use charges for fully depreciated assets; deferred maintenance costs; precontract costs; IR&D expenses and B&P expenses; royalties and other costs for use of patents; selling and distribution costs; travel and relocation costs; costs of idle facilities/capacity; severance pay to employees on support service contracts; plant reconversion; professional services; G&A expenses; and construction plant and equipment costs.

Selling and product distribution costs are also frequently questioned and are thus also particularly suitable for advance agreements. The government contends that such costs have limited allocability to government contracts. However, certain case law has proven otherwise and the government has had to agree to the overall allocability of the selling and product distribution costs of contractors that have both government and commercial contracts.

Indirect Cost Pools

Indirect costs are classified as overhead or G&A expenses. Overhead includes all indirect costs incurred for the production of goods and services, while G&A expenses are the overall costs of running a business. Overhead would include, for example, the electricity used to operate a plant. G&A expenses, on the other hand, would include the costs of running the accounting department. Overhead is allocated to products or services, while G&A expenses are allocated to cost accounting periods. Overhead and G&A expenses are not considered homogeneous and therefore usually should not be accumulated in the same indirect cost pool.

Indirect cost pools should be designed to permit allocations on the basis of the benefits received by the cost objectives. They should consider the reasons for incurring the costs and the logical connection between the costs accumulated. In other words, cost pools should be homogeneous. The FAR does not specify the number of cost pools a contractor should have, although it does caution that the number and composition of the cost pools should be governed by practical considerations. If substantially the same results can be obtained by using fewer cost pools, fewer cost pools should be used.

Allocations of indirect costs should not be unduly complicated. An allocation that is theoretically more accurate is not necessarily better because the greater the number of cost pools, the more complicated the process of accumulating, allocating, and cross-allocating indirect costs becomes.

The most common types of cost pools in a manufacturing environment are manufacturing, engineering, and material-related cost pools. The types of pools established depend on the types and number of the contractor’s organizational units and the kind of products or services provided. For example, if a contractor has several plants or business units with different indirect cost rates, separate pools may be established for each site. If, however, a contractor has several plants where the business mix is similar and a common manager is responsible for all of them, only one cost pool may be necessary. Other factors could influence this decision, such as the relative volume at each site and the materiality of the costs involved.

Once an allocation base for an indirect cost pool has been established, the base should be used consistently. All costs, including unallowable costs, should receive a pro rata allocation of the G&A expenses. So, if a contracting officer disallowed travel and per diem costs on a particular contract, a pro rata share of the G&A expenses is also unallowable.

Criteria for Establishing Cost Pools

The criteria for distinguishing between direct and indirect costs and for determining how many indirect cost pools to have are: (1) compliance with government procurement regulations; (2) maximization of cost recovery; (3) development of meaningful information for management decisions; and (4) achievement of precise yet practical allocations. These criteria often conflict, most apparently in the case of complying with procurement regulations while also maximizing recovery of costs.

Under fixed-price contracts, the amount the government reimburses is set by precontract negotiations, market prices, or catalog prices. Under cost-reimbursement contracts, the amount the government reimburses is less restricted. Therefore, contractors can maximize cost recovery by allocating as many indirect costs as are legitimate to cost-reimbursement contracts. Some contractors design their organizational structure to take maximum advantage of the different types of contracts they perform. For example, they might perform noncompetitive contracts in one business unit and competitive contracts in a different unit. In this way, they can develop costs and prices for each organizational unit and allocate indirect costs more advantageously.

Management officials need reliable data to conduct a business properly, and a contractor’s cost accounting system should be designed with this in mind. If a contractor’s cost structure is too complex or if it is overly responsive to other needs (e.g., the need to comply with government regulations or to maximize cost recovery), management may be left with little meaningful data on which to base day-to-day decisions. If, for example, a contractor segregates commercial and government contracts—both of which are profitable—into separate divisions and allocates a disproportionate share of costs to the government division, the commercial division may appear more profitable than it really is, and the government division may appear to be unprofitable.

The tradeoff that has to be considered in deciding how many indirect cost pools should be established is accuracy versus practicality. The greater the number of indirect cost pools, the greater the theoretical accuracy in identifying indirect costs with cost objectives. On the other hand, more indirect cost pools means having to collect and maintain additional cost accounting data; for each indirect cost pool established, the contractor must forecast indirect cost rates to use in pricing and negotiating contract prices. As cost pools proliferate, each pool collects a lesser share of total costs, and, as a result, forecasts of the indirect cost rates become increasingly unreliable.

Many government contractors progress from a simple cost accounting structure having only a single indirect cost pool to a much more elaborate cost accounting structure having many interrelated indirect cost pools. If all a contractor’s final cost objectives are similar, a single indirect cost pool is likely to be the best structure. That is, if a contractor produces only one type of product or service and also uses only one type of contract, then the use of only one cost pool would probably be acceptable to the government. For contractors that produce more than one product or service under various types of contracts, however, the government usually requires at least a segregation of G&A expenses from all other indirect costs.

For contractors with several plants or business units, it is unlikely that each site would have identical indirect cost rates, so separate pools should usually be established for each site. If, however, the business mix is similar at all the sites and a common manager is responsible for them all, there may be no need for individual rates. Other factors could influence this decision, such as the relative volume at each site and the materiality of the costs involved.

However, separate pools might be needed even at a single site. This might especially be true if different products, product lines, services, or departments exist at one site and the allocation base (e.g., direct labor dollars) varies significantly among the products, product lines, services, or departments. For example, if one department incurs significantly higher occupancy costs than the other but incurs identical labor costs, then separate cost pools by department should probably be established. Otherwise, each department would receive the same utility allocation.

Contractors have considerable discretion in deciding how to allocate costs to contracts. In numerous cases (e.g., ASBCA No. 11050, NASA BCA No. 873-10), the Boards of Contract Appeals have established that a contractor-selected allocation method should not be altered by the government unless the method produces inequitable results. The contractor’s method does not have to be the best alternative, but merely an equitable method.

Contractors should monitor the cost structure and periodically review conditions to ensure that the most advantageous cost structure is being used. Changed business conditions (e.g., replacement of manual labor with robotics, shift from a service to a product business line, opening of a new facility, changes in the competitive environment, development of new products, mergers and acquisitions) may demand a revised cost structure. Because of the CAS requirement to compute a cost impact statement for accounting changes, the timing of a cost structure change should consider the status of existing contracts, the fiscal period, and the expected date of significant new contracts.

Frequently, contractors seek to isolate all or a portion of government contract operations from commercial or other government operations to limit exposure to government reviews, to maximize cost recovery, or to achieve other business advantages. The organizational units created under these conditions are sometimes referred to as special business units. This approach receives considerable government scrutiny and is often not successful in achieving the desired results. The existence of separate legal entities does not have as much influence on the way the government reviews transactions as on the way costs are allocated or shared between those entities. The presence of shared facilities and services, common management, frequent transfer of personnel, intercompany projects, loaning of employees, etc., are all indicators of a single unit.

Often, to achieve adequate segregation of a special business unit, it is necessary to take actions that are not the most financially prudent. For example, avoiding the use of shared facilities and management might result in higher costs for the overall operation.

Accordingly, contractors would be wise to minimize the number of indirect cost pools. Usually, contractors find it much more difficult to convince the government to allow an indirect cost pool to be deleted than to add a new cost pool; the government usually assumes that the more cost pools a contractor has, the better.

Directly Associated Cost

The term “directly associated cost” refers to “any cost which is generated solely as a result of the incurrence of another cost, and which would not have been incurred had the other cost not been incurred.” The term “directly associated cost” is used to identify incremental costs associated with specifically unallowable costs. CAS 405, Accounting for Unallowable Costs, uses it to establish a “but for” relationship between principal costs and associated costs. A principal cost is a cost that clearly results from an action that gives rise to unallowable costs (such as the salary of an employee engaged in an unallowable cost activity such as lobbying on a full-time basis). A directly associated cost is any incremental cost attributable to the unallowable activity (such as fringe benefits or office supplies for a full-time lobbyist). In short, a cost is considered to be directly associated with a principal cost if it would not have been incurred “but for” the incurrence of the principal cost.

If directly associated costs are included in a cost pool that is allocated using a base that includes the related unallowable cost, the directly associated costs should remain in the cost pool when calculating the amount of the directly associated costs to be disallowed. Keeping the unallowable costs in the base ensures that an allocable share of the directly associated costs will be disallowed.

For example:

| Indirect cost pool expenses | $1,200 |

| Indirect cost pool allocation base (direct labor dollars) |

$ 800 |

| Indirect cost pool rate ($1,200/$800) | 150% |

Assume that, for some reason, $50 of direct labor is determined to be unallowable. Because the unallowed labor costs of $50 are included in the allocation base, the application of the indirect cost rate (150 percent) to the unallowed labor is sufficient to ensure that all directly associated costs are included in the unallowed costs. In this case, the total unallowed costs are $125 ($50 of direct labor plus 150 percent of $50, or $75, of indirect costs).

In all other cases, the directly associated costs, if material in amount, must be purged from the cost pool as unallowable costs. For example, assume that the unallowable activity is not direct labor, but some indirect cost (such as indirect labor). Assume also that the unallowable cost is $110 ($50 of principal costs plus $60 of directly associated costs). The recalculated indirect cost rate is then:

| Indirect cost pool expenses ($1,200-$110) |

$1,090 |

| Indirect cost pool allocation base | $800 |

| Indirect cost pool rate ($1,090/$800) |

136.25% |

In determining the materiality of directly associated costs, consideration should be given to the significance in dollars of the costs, the cumulative effect of the costs on cost pools, and the ultimate effect of the costs on government contracts. The salaries of employees who participate in activities that generate unallowable costs are treated as directly associated costs to the extent of time spent on the proscribed activity (if it is material). The time spent on such activities should be compared to total time spent on company activities to determine if the costs are material. Time spent by an employee outside normal working hours should not be considered unless the employee engages in company activities outside normal working hours so frequently that those activities are clearly part of the employee’s regular duties. This might particularly be true of entertainment activities carried on outside normal working hours.

Cosmetically Low Rates

Sometimes a prime motivation in establishing direct versus indirect costs, groupings of indirect costs, and allocation bases for indirect costs is a desire to achieve low indirect cost rates. Even though reclassifying indirect costs as direct to obtain lower indirect cost rates does not change the total cost, unsophisticated buyers are frequently impressed by low individual cost rates, especially for cost-reimbursement contracts and T&M contracts in which the final price cannot be determined until the goods or services are actually delivered.

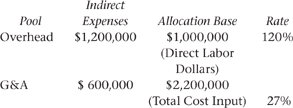

Customers offten complain that a particular indirect cost rate is “too high.” This standalone statement is seldom warranted. For example, assume that a company has a single indirect cost rate of 180 percent:

| Allocation | ||

| Indirect | Base—Direct | |

| Expenses | Labor Dollars | Rate |

| $1,800,000 | $1,000,000 | 180% |

That seems high, but is it? Let’s change the accounting to segregate overhead and G&A:

That’s better. But let’s add a fringe benefit cost pool as well:

That’s even better. Now let’s change the allocation base for overhead from direct labor dollars to direct labor costs, i.e., fringe benefits plus direct labor dollars:

This is even better. However, this exercise only illustrates the dangers in reaching hasty conclusions on the propriety of an indirect cost rate. A better measure is the labor multiplier, i.e., the total indirect cost additives divided by the direct labor dollars. In practice, these additives include profit or markup, but for illustration purposes, markup is not included in the following discussion.

In this example, the multiplier is consistently 1.80 for each accounting variation. The multiplier negates most differences due to accounting structure. (It does not accommodate differences between classification of costs as direct versus indirect.) In addition, many companies compare their multiplier to others or to a perceived industry norm. For example, low-tech services where the customer provides facilities may result in a multiplier of only 1.30, whereas a high-tech business with elaborate facilities may result in a multiplier over 4.0

The use of automated production processes has a dual impact on indirect cost rates. First, the traditional allocation base of direct labor dollars is reduced. Second, the indirect costs related to equipment will likely increase because of the purchase of additional equipment. These conditions can have a dramatic impact on the rate, because the numerator increases and the denominator decreases. Some may simply interpret the resulting rate increase as a sign of inefficiency. This interpretation is shallow and erroneous, however, because the true measure of efficiency is total cost, not indirect rates.

Activity-based costing (ABC) has significantly affected traditional views of cost accounting and product costing. This approach does not focus on unit costs, but on costs of activities, and it acknowledges that not all costs are unit-dependent or fixed costs. For example, product costs are often influenced by a measure of activities such as number of units in a batch, physical measurements of the product, number of machine set-ups, number of parts involved, and number of engineering changes.

ABC does not use allocation bases consisting of noncost elements in lieu of costs, but first assigns costs to activities and then relates activities to products using measures of activity—termed cost drivers—that are not limited to allocations based on costs. The concept is useful in a competitive environment in which substantial data are available and multiple products are being manufactured.

The ABC application begins with matching costs to activities. Next, a cost driver is selected that best measures the activity and serves as the best allocation base for the cost of the activity. A schematic of the operations is helpful in identifying activities and the flow of product and cost.

Segregation of Unallowable Costs

Both CAS 405, Accounting for Unallowable Costs, and the FAR require the segregation of all expressly unallowable costs. Expressly unallowable costs include those specifically cited in the regulations or a contract as unallowable and those disputed cost determinations that have been upheld by a court or BCA. During an appeal process (i.e., after a DCAA determination or a contracting officer decision adverse to the contractor but before a court or BCA decision), these costs may be included in billings, claims, or proposals as long as they are identified in sufficient detail to provide adequate disclosure.

Because government cost principles may be revised from time to time, a contractor must keep abreast of developments to avoid allegations of not having properly segregated unallowable costs. Distinctions between allowable and unallowable costs are sometimes not easy to make. Areas that require careful review and documentation include congressional lobbying versus legislative liaison, executive branch lobbying based on merits versus liaison based on other than merits, B&P expenses versus marketing costs, and entertainment versus business conference and meeting expenses.

To screen unallowable costs, the contractor should establish policies to determine what costs will be excluded and how those costs will be removed from any claims or submissions to the government. Multi-di-vis-ion-al contractors must also consider the need for uniform policies and practices between organizational units. A vital step toward this effort is to involve the employees who incur the costs. These employees must have clear policies on entertainment costs, business conference costs, and travel costs. When claiming reimbursements from the company, the employees should be required to identify any costs that may be unallowable.

This policy alone is not sufficient. The company must also have procedures in place to routinely screen critical transactions as they occur and as they are recorded. It must have clear instructions for these procedures to ensure consistent application of common policies.

FAR 42.709 provides guidance for assessing penalties when contractors claim unallowable costs. The penalties cover final indirect cost rate proposals and the final statement of costs incurred or estimated to be incurred under a fixed-price incentive contract. The penalties pertain to all contracts in excess of $500,000, except fixed-price contracts without cost incentives or any firm-fixed-price contracts for the purchase of commercial items.

If the unallowable indirect cost claimed is expressly unallowable under a cost principle in the FAR or an executive agency supplement to the FAR, the penalty is equal to: (1) the amount of the disallowed costs allocated to contracts that are subject to this section for which an indirect cost proposal has been submitted; plus (2) interest on the paid portion, if any, of the disallowance. If the direct cost was determined to be unallowable for that contractor before proposal submission, the penalty is two times this amount. These penalties are in addition to other administrative, civil, and criminal penalties provided by law. It is not necessary for unallowable costs to have been paid to the con-tractor for a penalty to be assessed.

FAR 42.709-2 establishes responsibilities for penalty applications. The cognizant contracting officer is responsible for: (1) determining whether the penalties should be assessed; (2) determining whether such penalties should be waived; and (3) referring the matter to the appropriate criminal investigative organization for review and for appropriate coordination of remedies, if there is evidence that the contractor knowingly submitted unallowable costs. The contract auditor, in the review and/or the determination of final indirect cost proposals for contracts subject to this section, is responsible for: (1) recommending to the contracting officer which costs may be unallowable and subject to the penalties; (2) providing rationale and supporting documentation for any recommendation; and (3) referring the matter to the appropriate criminal investigative organization for review and for appropriate coordination of remedies, if there is evidence that the contractor knowingly submitted unallowable costs.

Unless a waiver is granted, the cognizant contracting officer will assess the penalty when: (1) the submitted cost is expressly unallowable under a cost principle in the FAR or an executive agency supplement that defines the allowability of specific selected costs; or (2) the submitted cost was determined to be unallowable for that contractor prior to submission of the proposal. Prior determinations of unallowability may be evidenced by: (1) a DCAA Form 1 that the contractor did not appeal and that was not withdrawn by the issuing agency; (2) a contracting officer final decision that was not appealed; or (3) a prior BCA or court decision involving the contractor that upheld the cost disallowance.

The cognizant contracting officer is to waive the penalties at 42.709-1(a) when at least one of the following conditions exists:

The contractor withdraws the proposal before the government formally initiates an audit of the proposal and the contractor submits a revised proposal. (An audit will be deemed to be formally initiated when the government provides the contractor with written notice, or holds an entrance conference, indicating that audit work on a specific final indirect cost proposal has begun.)

The amount of the unallowable costs under the proposal that are subject to the penalty is $10,000 or less.

The contractor demonstrates, to the cognizant contracting officer’s satisfaction, that it has established policies and personnel training and an internal control and review system that provide assurance that unallowable costs subject to penalties are precluded from being included in the contractor’s final indirect cost rate proposals, and the unallowable costs subject to the penalty were inadvertently incorporated into the proposal (i.e., their inclusion resulted from an unintentional error).

Penalties related to indirect cost rate proposals submitted before October 23, 1992, are assessed if the claimed costs were unallowable by “clear and convincing” evidence. On or after this date, penalties are assessed if the costs were “expressly unallowable,” a less harsh, more objective standard.

Some government auditors have taken the position that penalties for claiming unallowable costs may be imposed even after an audit report is issued and the matter has been settled with the contracting officer. This guidance states that the penalty provision will be considered applicable even if a contracting officer has neglected to include the legislatively mandated clause in the contract. Until 1989, this guidance excluded issues of cost reasonableness and allocability as being subject to penalties. However, the most recent guidance is silent on these categories of cost disallowance.