CHAPTER 8

Contract Price Negotiation and Profit Guidelines

In late 2010 the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA) greatly reduced the number of price proposal reviews and increased the intensity of the reviews performed. Price proposals for fixed-price type contracts under $10 million and for cost-type contract proposals under $100 million will seldom be reviewed. However, for fixed-price proposals over $100 million and cost-type proposals over $250 million, the audit will be much more in-depth than previously. For these significant proposals, DCAA will conduct a detailed “walk-through” of each proposal before an audit begins. This process can take as much as a full week and may involve the contracting officer and every contractor employee who participated in proposal preparation.

After an auditor has submitted a report on a price proposal evaluation to the contracting officer, price negotiation will take place if the contractor is selected to be a potential candidate for the contract. Since this phase of the procurement process is a “negotiation,” each party will have to give and take on the final price. The contractor must realize that the contracting officer is going to question certain costs going into the total proposed price, based on advice furnished by the auditor or other technical advisors. In the price negotiation, the contractor should be fully alert to the implications of that price on the company.

Price is composed of two elements: cost and markup. Although cost represents the larger portion of price, markup (profit or fee) is at least as important to the contractor in negotiations. The more accurate term for what the government regulations refer to as “profit” on fixed-price type contracts and “fee” on cost type contracts is “markup.”

Despite the regulatory use of the terms “profit” and “fee” in casual government contracting jargon, the terms are used somewhat interchangeably. The true “profit” or net income for a contractor is what the business earns after deductions for unallowable costs and taxes and is usually referred to as “net after taxes.” Profit or fee prenegotiation objectives do not necessarily represent net income to contractors. Rather, they represent that element of the potential total remuneration that contractors may receive for contract performance over and above allowable costs.

How much profit should a contractor seek and how can a certain level of profit be justified? Contractors are not required to submit details of their profit or fee objectives or to follow a particular format or rationale in their profit calculations; government agencies, however, usually must follow structured procedures in evaluating proposed profit levels. Contractors may use the government procedures, and many, in fact, do. But even those who use a different technique would be wise to become familiar with the government’s procedures in preparation for negotiations.

Contractors also should be aware of statutory limitations on profit. A contracting officer may not negotiate a price or fee that exceeds the following statutory limitations, imposed by 10 U.S.C. 2306(e) and 41 U.S.C. 254(b):

For experimental, developmental, or research work performed under a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract, the fee may not exceed 15 percent of the contract’s estimated cost, excluding fee.

For architect-engineer services for public works or utilities, the contract price or the estimated cost and fee for production and delivery of designs, plans, drawings, and specifications may not exceed 6 percent of the estimated cost of construction of the public work or utility, excluding fees.

For other cost-plus-fixed-fee contracts, the fee may not exceed 10 percent of the contract’s cost, excluding fee.

It is important to note that these limitations are based on estimated costs, not actual costs. The relationship of profit to estimated costs cannot exceed these amounts; however, the relationship of profit to the actual costs may result in a percentage greater than these amounts.

During World War II, Congress established the Renegotiation Board. The express purpose of this board was to review contracts, and the profit/fee each had earned. In particular, the board reviewed fixed-price contracts for “excessive” contractor profit. Needless to say, this board was not viewed fondly by the contractor community. The enabling legislation for the board finally lapsed and Congress did not renew it. Fortunately, no such legislation exists today. Unfortunately, some people still improperly refer to excess or windfall profits—a concept no longer supported by any regulatory basis.

Although the FAR does not elaborate on profit guidelines, each agency has the authority to do so in its supplement to the FAR. The Department of Defense (DOD) has established its own guidelines, as has the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The former guidelines emphasize performance risk, contract risk, and contract financing. The latter guidelines are similar, but reduce profit objectives by the amount of cost of money claimed by the contractor. Most other agencies do not have formal profit guidelines. Unofficially, some agencies seek little or no profit on consultant costs, subcontract costs, and other selected cost items.

GOVERNMENT VS. COMMERCIAL PROFIT

A basic concept (which contractors hope is being addressed and possibly changed) is the fact that contracting with the government is usually driven by cost while commercial transactions are generally driven by price. The result of this business arrangement is that a considerably lower level of profit is derived from government contracts. That is not to say that as a buying public we are being overcharged. Conversely, it simply means that the government is not prone to use taxpayer-backed funds to provide a reasonable profit to contractors. Because of this fact in government contract transactions, some contractors refuse to do business with the government.

This reluctance has created two distinct industrial bases, one commercial and one governmental. Many companies are either 100 percent commercial or 100 percent government. There are instances where the product/service mix is both commercial and government. This has many times been the result of a company’s ability to use some of its products that were originally designed or developed for the government in the commercial marketplace.

Despite the lower profits from government business, many companies remain contractors. The reasons vary from performing the work for the sake of national defense to being enmeshed in government business and unable to break out of it. Some others may be in the position of incurring related costs anyway so they might as well have some of the marginal costs absorbed by performing on contracts. Whatever the reason, contractors are many and varied, and have a variety of reasons, other than just being profitable, for conducting government business.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE GUIDELINES

DOD has promulgated guidelines for evaluating a contractor’s requests for profit or fee. The current version was established in 1987 as a result of a DOD profit survey, which recommended that the guidelines focus on performance rather than cost elements.

Several minor revisions have been made from time to time since 1987. Most significantly, for a period of time no markup was allowed on G&A costs—this no longer applies. During the time that G&A did not carry a markup, many contractors properly reclassified costs from G&A to overhead.

Weighted Guidelines Method

This method, which is found in DFARS 215.404-70, is DOD’s structured approach for performing profit analysis in contract actions where the price is to be negotiated. For many years, the guidelines were based on the contract-estimated costs, often by cost element such as direct labor, direct materials, subcontracts, etc. In 1986, the DOD guidelines were revised in response to congressional concern that previous changes to the regulations had created profit beyond a level that was warranted under the circumstances. The goal of the new guidelines was to lower profit.

The guideline changes were significant and not merely a reshuffling of prior factors. First, guidelines for manufacturing, services, and research and development contracts are no longer separate. Second, the guidelines attempt to decrease the reliance on estimated costs and stress the technical aspects of the proposal when establishing the profit level.

Third, the guidelines integrate the financing considerations involved in the contractual terms into the calculation of profit. In other words, they make the extent of progress payments a factor in determining how much profit will be earned. Fourth, the guidelines place greater emphasis on facilities capital. This emphasis is selective in that certain assets will generate more potential profit than other assets.

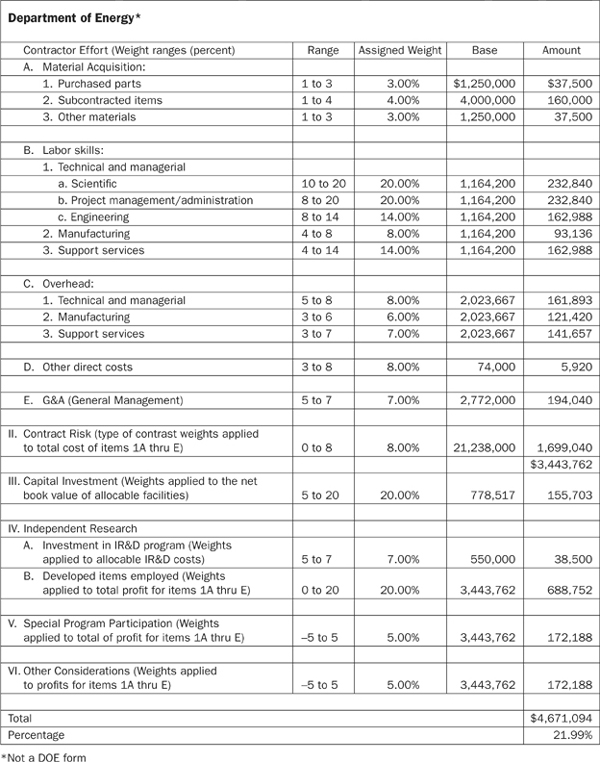

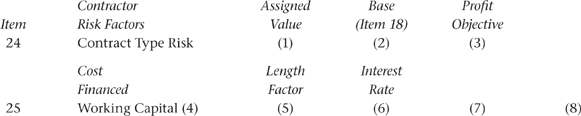

An example of the DOD weighted guidelines method is presented in Figure 26.

Profit Objective Determination

The DOD contracting officer is required to use the weighted guidelines method or an alternate structured approach to determine the prenegotiation profit objective for any negotiated contract action that requires cost analysis, except on cost-plus-award-fee contracts. An alternate structured approach can be used for contracts under $700,000, architect-engineer contracts, construction contracts, contracts primarily requiring delivery of material supplied by subcontractors, termination settlements, and unusual situations. However, the alternate approach must specifically address the same four basic elements—performance risk, contract risk, working capital-adjustment, and facilities capital employed—used in the weighted guidelines method.

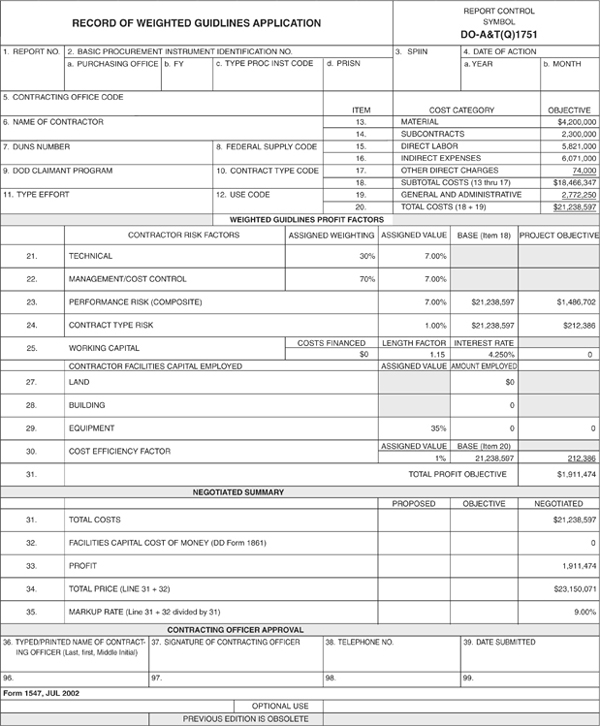

DD Form 1547, Record of Weighted Guidelines Method Application, implements DOD’s structured approach for performing the profit analysis necessary to develop a prenegotiation profit objective. It focuses on four profit factors: (1) performance risk; (2) contract-type risk; (3) facilities capital employed; and (4) cost efficiency.

The contracting officer assigns a value to each profit factor; the value multiplied by the base results in the profit objective for that factor. Each profit factor has a normal value and a designated range of values. The normal value represents average conditions on the prospective contract when compared to all goods and services acquired by DOD. The designated range provides values based on above normal or below normal conditions. In the price negotiation documentation, the contracting officer need not explain assignment of the normal value, but should address conditions that justify assignment of other than the normal value.

Figure 26

EXAMPLE OF DOD WEIGHTED GUIDELINES METHOD

Performance Risk

The performance risk profit factor addresses the contractor’s degree of risk in fulfilling the contractual requirements. The factor consists of two parts: (1) technical—the technical uncertainties of performance; and (2) management—the degree of management effort necessary to ensure that contract requirements are met.

Each factor is an integral part of developing the composite profit value for performance risk. The contracting officer weights each factor according to the contractor’s performance risk in providing the supplies or services required by the contract. While any value may be assigned within the designated range, the maximum and minimum values will be restricted to cases where performance risk is substantially above or below normal. The following example demonstrates how a composite profit value for performance risk is calculated.

The profit objective amount is computed by multiplying a composite profit value, assigned by the contracting officer (in this example 4.6%), times total contract costs, excluding facilities capital cost of money.

| Normal Value |

Designated Range |

|

| Standard | 5% | 3% to 7% |

| Technology Incentive | 9% | 7% to 11% |

Contracting officers may use the alternate designated range for research and development and service contractors when these contractors require relatively low capital investment in buildings and equipment compared to the defense industry overall. If the alternate designated range is used, no profit will be given for facilities capital employed.

Technical Risk. This criterion focuses on the contract requirements and the critical performance elements in the statement of work or specifications. Factors considered include the technology being applied or developed by the contractor, technical complexity, program maturity, performance specifications and tolerances, delivery schedule, and the extent of warranty or guarantee coverage.

A higher than normal value may be assigned where there is substantial technical risk, such as when the contractor is: (1) either developing or applying advanced technologies; (2) manufacturing items using specifications with stringent tolerance limits; (3) using highly skilled personnel or state-of-the-art machinery; (4) performing services and analytical efforts of utmost importance to the government and to exacting standards; (5) through independent development and investment, reducing the government’s risk or cost; (6) accepting an accelerated delivery schedule to meet DOD requirements; or (7) assuming additional risk through warranty provisions.

Extremely complex, vital efforts to overcome difficult technical obstacles that require personnel with exceptional abilities, experience, and professional credentials may justify a value significantly above normal. A maximum value may be assigned when there is development or initial production of a new item, particularly if performance or quality specifications are tight or there is a high degree of concurrent development or production.

A lower than normal value may be assigned in those cases where the technical risk is low, such as when the contractor is acquiring off-the-shelf items, specifying relatively simple requirements, applying little complex technology, performing efforts that do not require highly skilled personnel, performing routine efforts, performing on mature programs and procedures, or performing follow-on efforts or repetitive-type procurements. In addition, a significantly lower than normal value could be assigned for routine services, production of simple items, rote entry or routine integration of government-furnished information, or simple operations with government-furnished property.

Management Risk. This criterion considers the management effort involved on the part of the contractor to integrate the resources (including raw materials, labor, technology, information, and capital) necessary to meet contract requirements. The evaluation should: (1) assess the contractor’s management and internal control systems using contracting office information and reviews made by field contract administration offices or other DOD field offices; (2) assess the management involvement expected on the individual contract action; (3) consider the degree of cost mix as an indication of the types of resources applied and value added by the contractor; and (4) consider the contractor’s support of federal socioeconomic programs, such as small business concerns, and small business concerns owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.

A higher than normal value may be assigned in those cases where the management effort is intense, such as when the value added by the contractor is both considerable and reasonably difficult, the effort involves a high degree of integration or coordination, or the contractor has a substantial record of active participation in federal socioeconomic programs. A maximum value may be assigned when the effort requires large-scale integration of the most complex nature, involves major international activities with significant management coordination (e.g., offsets with foreign vendors), or has critically important milestones.

A lower than normal value may be assigned in those cases where the management effort is minimal, such as when, in a mature program, many end-item deliveries have been made, the contractor adds minimum value to an item, efforts are routine and require minimal supervision, the contractor provides poor quality, untimely proposals, the contractor fails to provide an adequate analysis of subcontractor costs, or the contractor does not cooperate in the evaluation and negotiation of the proposal.

A value significantly below normal may be justified when reviews performed by the field contract administration offices disclose unsatisfactory management and internal control systems (e.g., quality assurance, property control, safety or security) or the effort requires an unusually low degree of management involvement.

The technology factor is primarily applicable to acquisitions that include development, production, or application of innovative new technologies. The technology incentive range does not apply to efforts restricted to studies, analyses, or demonstrations that have a technical report as their primary deliverable. The technology incentive range should be used when contract performance includes the introduction of new, significant technological innovation. Innovation may be in the form of development or application of new technology that fundamentally changes the characteristics of an existing product or system and that results in increased technical performance, improved reliability, or reduced costs, or a new product or system that achieves significant technological advances over the product or system it is replacing.

Contract-Type Risk and Working Capital Adjustment

This factor focuses on the degree of cost risk accepted by the contractor under varying contract types. The working capital adjustment is an adjustment added to the profit objective for contract-type risk. It only applies to fixed-price contracts that provide for progress payments. Although it uses a formula approach, it is not intended to be an exact calculation of the cost of working capital. Its purpose is to give general recognition to the contractor’s cost of working capital under varying contract circumstances, financing policies, and the economic environment.

The following extract from DD 1547 is annotated to explain the process.

(1) Select a value from the list of contract types using the appropriate evaluation criteria.

(2) Insert the total allowable costs excluding the facilities capital cost of money.

(3) Multiply (1) by (2).

(4) Only complete this block when the prospective contract is a fixed-price contract containing provisions for progress payments.

(5) Insert the amount computed per the Costs Financed paragraph of this section.

(6) Insert the appropriate figure from the Contract Length paragraph of this section.

(7) Use the interest rate established by the Secretary of the Treasury (see DFARS 230.7101-1(a)). Do not use any other interest rate.

(8) Multiply (5) by (6) by (7). This is the working capital adjustment. It is not to exceed 4 percent of the allowable costs, excluding facilities capital cost of money.

Contract values for normal and designated ranges are:

(1) “No financing” means that the contract either does not provide progress payments, or provides them only on a limited basis, such as financing of first articles. A working capital adjustment is not computed.

(2) “With financing” means progress payments. When progress payments are present, compute a working capital adjustment.

(3) For the purpose of assigning profit values, treat a fixed-price contract with redeterminable provisions as if it were a fixed-price-incentive contract with below normal conditions.

(4) Cost-plus contracts do not receive the working capital adjustment.

(5) These types of contracts are considered cost-plus-fixed-fee contracts for the purposes of assigning profit values. They do not receive the working capital adjustment in Block 26. However, they may receive higher than normal values within the designated range to the extent that portions of cost are fixed.

(6) When the contract includes provisions for performance-based payments, do not compute a working capital adjustment.

The contracting officer should consider elements that affect contract-type risk, such as length of contract, adequacy of cost data for projections, economic environment, nature and extent of subcontracted activity, protection provided to the contractor under contract provisions (e.g., economic price adjustment clauses), ceilings and share lines contained in incentive provisions, and risks associated with contracts for foreign military sales (FMS) that are not funded by U.S. appropriations.

The contracting officer will assess the extent to which costs have been incurred prior to definitization of the contract action. The assessment will include any reduced contractor risk on both the contract before definitization and the remaining portion of the contract. When costs have been incurred prior to definitization, the contract-type risk is generally regarded to be in the low end of the designated range. If a substantial portion of the costs has been incurred prior to definitization, the contracting officer may assign a value as low as 0 percent, regardless of contract type.

A higher than normal value may be assigned in those cases where there is substantial contract-type risk, such as when the contract involves effort with minimal cost history, is long-term without provisions protecting the contractor (particularly when there is considerable economic uncertainty), includes incentive provisions (e.g., cost or performance incentives) that place a high degree of risk on the contractor, or has FMS sales (other than those under DOD cooperative logistics support arrangements or those made from government inventories or stocks) where the contractor can demonstrate that there are substantial risks above those normally present in DOD contracts for similar items.

A lower than normal value may be assigned in cases where contract risk is low, such as when the contract involves a very mature product line with extensive cost history, is relatively short-term, contains provisions that substantially reduce the contractor’s risk, or includes incentive provisions that place a low degree of risk on the contractor.

The costs financed equal total costs multiplied by the portion (percent) of costs financed by the contractor. Total costs equal all allowable costs, excluding facilities capital cost of money, reduced as appropriate when: (1) the contractor has little cash investment (e.g., subcontractor progress payments liquidated late in the period of performance); (2) some costs are covered by special financing provisions, such as advance payments; or (3) the contract is multiyear and there are special funding arrangements.

The portion financed by the contractor is generally the portion not covered by progress payments (i.e., 100 percent minus the customary progress payment rate). For example, if a contractor receives progress payments at 75 percent, the portion financed by the contractor is 25 percent. On contracts that provide flexible progress payments or progress payments to small businesses, the customary progress payment rate for large businesses should be used.

The contract length factor is the period of time that the contractor has a working capital investment in the contract. The factor is based on the time necessary for the contractor to complete the substantive portion of the work, and is not necessarily the period of time between contract award and final delivery (or final payment). Periods of minimal effort should be excluded, should not include periods of performance contained in option provisions, and should not, for multiyear contracts, include periods of performance beyond those required to complete the initial program year’s requirements.

The contracting officer should use the following table to select the contract length factor, should develop a weighted average contract length when the contract has multiple deliveries, and may use sampling techniques provided they produce a representative result.

| Period to Perform | Contract |

| Substantive Portion | Length |

| (in months) | Factor |

| 21 months or less | .40 |

| 22 to 27 months | .65 |

| 28 to 33 months | .90 |

| 34 to 39 months | 1.15 |

| 40 to 45 months | 1.40 |

| 46 to 51 months | 1.65 |

| 52 to 57 months | 1.90 |

| 58 to 63 months | 2.15 |

| 64 to 69 months | 2.40 |

| 70 to 75 months | 2.65 |

| 76 months or more | 2.90 |

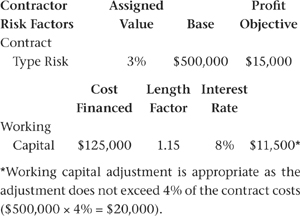

For example, a contractor is to be awarded a negotiated contract for assembly work. The contracting officer’s prenegotiation cost objective for each is $500,000. The period of performance is 40 months, with assemblies being delivered in the 34th, 36th, 38th, and 40th month of the contract (average period is 37 months). The contractor will receive progress payments at 75 percent (contractor portion is 25 percent), and the current interest rate is 8 percent.

Facilities Capital Employed

This factor focuses on encouraging and rewarding aggressive capital investment in facilities that benefit DOD. It recognizes both the facilities capital that the contractor will employ in contract performance and the contractor’s commitment to improving productivity.

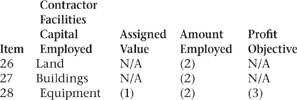

The following extract from DD Form 1547 has been annotated to explain the process:

(1) Select a value from the list of Normal and Designated Ranges using criteria from the Evaluation section.

(2) Use the allocated facilities capital attributable to land, buildings, and equipment, as derived in DD 1861, Contract Facilities Capital Cost of Money (see Figure 27). This form can only be completed after application of the CAS form for computing the cost of money (see Figure 28).

In addition to the net book value of facilities capital employed, facilities capital that is part of a formal investment plan should be considered if the contractor submits reasonable evidence that achievable benefits to DOD will result from the investment, and the benefits of the investment are included in the forward pricing structure. If the value of intracompany transfers has been included at cost (i.e., excluding profit), the allocated facilities capital attributable to the buildings and equipment of those corporate divisions supplying the intracompany transfers should be added to contractor’s allocated facilities capital. This addition should not be made if the value of intracompany transfers has been included at price (i.e., including profit).

Values: Normal and Designated Ranges

| Normal | Designated | |

| Asset Type | Value | Value |

| Land | 0% | N/A |

| Buildings | 0% | N/A |

| Equipment | 17.5% | 10% to 25% |

In evaluating facilities capital employed, the contracting officer should relate the usefulness of the facilities capital to the goods or services being acquired under the particular contract. The contracting officer should also analyze the productivity improvements and other anticipated industrial base-enhancing benefits resulting from the facilities capital investment, including the economic value of the facilities capital (e.g., physical age, undepreciated value, idleness, expected contribution to future defense needs) and the contractor’s level of investment in defense-related facilities as compared with the portion of the contractor’s total business that is derived from DOD.

In addition, the contracting officer should consider any contractual provisions that reduce the contractor’s risk of investment recovery, such as termination protection clauses and capital investment indemnification. Also, the contracting officer should ensure that increases in facilities capital investments are not merely asset revaluations attributable to mergers, stock transfers, takeovers, sales of corporate entities, or similar actions.

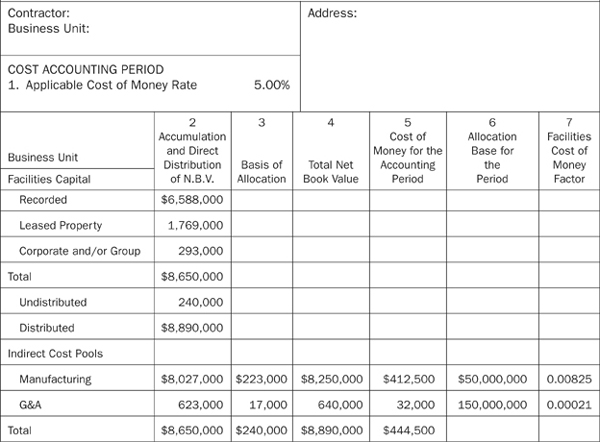

Figure 27

DD 1861—CONTRACT FACILITIES CAPITAL COST OF MONEY

Figure 28

FACTORS COMPUTATION FOR FACILITIES CAPITAL COST OF MONEY

A higher than normal value may be assigned if the facilities capital investment has direct, identifiable, and exceptional benefits. Indicators are: (1) new investments in state-of-the-art technology that reduce acquisition costs or yield other tangible benefits such as improved product quality or accelerated deliveries; (2) investments in new equipment for research and development applications; or (3) contractor demonstrates that the investments are over and above the normal capital investments necessary to support anticipated requirements of DOD programs.

A value significantly above normal may be assigned when there are direct and measurable benefits in efficiency and significantly reduced acquisition costs on the effort being priced. Maximum values apply only to those cases where the benefits of the facilities capital investment are substantially above normal. A lower than normal value may be assigned if the facilities capital investment has little benefit to DOD. Indicators are: (1) allocations of capital apply predominantly to commercial product item line items; (2) investments are for furniture and fixtures, home or group level administrative offices, corporate aircraft, hangars, or gymnasiums; or (3) the facilities are old or largely idle. A value significantly below normal may be assigned when a significant portion of defense manufacturing is performed in an environment characterized by outdated, inefficient, and labor-intensive capital equipment.

Cost Efficiency Factor

This special factor provides an incentive for contractors to reduce costs. To the extent that the contractor can demonstrate cost reduction efforts that benefit the pending contract, the contracting officer may increase the pre-negotiation profit objective by an amount not to exceed 4 percent of total objective cost. The following criteria are used to determine if using this factor is appropriate:

The contractor’s participation in single-process initiative improvements.

Actual cost reductions achieved on prior contracts.

Reduction or elimination of excess or idle facilities.

The contractor’s cost reduction initiatives (e.g., competition advocacy programs, technical insertion programs, obsolete parts control programs, spare parts pricing reform, value engineering, outsourcing of functions such as information technology). Metrics developed by the contractor such as fully loaded labor hours (i.e., cost per labor hour, including all direct and indirect costs) or other productivity measures may provide the basis for assessing the effectiveness of the contractor’s cost reduction initiatives over time.

The contractor’s adoption of process improvements to reduce costs.

Subcontractor cost reduction efforts.

The contractor’s effective incorporation of commercial items and processes.

The contractor’s investment in new facilities when such investments contribute to better asset utilization or improved productivity.

NASA GUIDELINES

Agencies other than DOD often follow different guidelines in addressing profit. NASA, in the NASA FAR Supplement, takes an approach similar to the DOD method for a structured profit or fee objective.

Of special interest to contractors is NASA’s policy toward facilities capital cost of money. According to NASA regulations, when facilities capital cost of money is included as an item of cost in the contractor’s proposal, it cannot be included in the cost base for calculating profit/fee. In addition, a reduction in the profit/fee objective will be made in the amount equal to the facilities capital cost of money allowed in accordance with FAR 31.205-10(a)(2). The regulations also state that CAS 417, Cost of Money As an Element of the Cost of Capital Assets Under Construction, should not appear in contract proposals. These costs are included in the initial value of a facility for purposes of calculating depreciation under CAS 414.

Figure 29 is an example of the application of NASA profit/fee guidelines. As of July 1999, NASA was considering adopting the DOD profit/fee guidelines.

OTHER AGENCIES’ GUIDELINES

Other agencies address profit and facilities capital cost of money in varying ways. In some instances, they have incorporated a weighted guideline type of approach. In other cases, the subject of facilities capital cost of money is addressed in the supplemental regulation; however, it is seldom addressed in actual contract negotiation. Accordingly, a potential government contractor should either review the pertinent regulations of the agency he will be dealing with, or seek advice from a knowledgeable professional source.

The Department of Energy (DOE) does not have specific forms for profit/fee negotiations. However, in narrative form, the guidelines are very similar to the NASA guidelines. Figure 30 is an example of the application of DOE guidelines.

Figure 29

EXAMPLE OF APPLICATION OF NASA PROFIT/FEE GUIDELINES

Figure 30

EXAMPLE OF APPLICATION OF DOE GUIDELINES