Incident Response

Bad guys will follow the rules of your network to accomplish their mission.

—RON SCHAFFER, SANS INCIDENT DETECTION SUMMIT

In this chapter, you will learn how to

![]() Understand the foundations of incident response processes

Understand the foundations of incident response processes

![]() Implement the detailed steps of an incident response process

Implement the detailed steps of an incident response process

![]() Describe standards and best practices that are involved in incident response

Describe standards and best practices that are involved in incident response

Incident response is becoming the new norm in security operations. The reality is that keeping adversaries off your network and preventing unauthorized activity is not going to provide the level of security your enterprise requires. This means the system needs to be able to operate in a state of compromise yet still achieve the desired security objectives. Your mind-set has to change from preventing intrusion and attack to preventing loss.

This chapter explores the use of an incident response function to achieve the goals of minimizing loss under all operating conditions. This will mean a shift in focus and a change in priorities as well as security strategy. These efforts can succeed only on top of a solid foundation of security fundamentals as presented earlier in the book, so this is not a starting place but rather the next step in the evolution of defense.

Foundations of Incident Response

Foundations of Incident Response

An incident is any event in an information system or network where the results are different than normal. Incident response is not just an information security operation. Incident response is an effort that involves the entire business. The security team may form a nucleus of the effort, but the key tasks are performed by many parts of the business.

Incident response is a term used to describe the steps an organization performs in response to any situation determined to be abnormal in the operation of a computer system. The causes of incidents are many, from the environment (storms) to errors on the part of users to unauthorized actions by unauthorized users, to name a few. Although the causes may be many, the results can be sorted into classes. A low-impact incident may not result in any significant risk exposure, so no action other than repairing the broken system is needed. A moderate-risk incident will require greater scrutiny and response efforts, and a high-level risk exposure incident will require the greatest scrutiny. To manage incidents when they occur, a table of guidelines for the incident response team needs to be created to assist in determining the level of response.

A successful incident response effort requires two components, knowledge of one’s own systems and knowledge of the adversary. The ancient warrior/philosopher Sun Tzu explains it well in The Art of War: “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Two major elements play a role in determining the level of response. Information criticality is the primary determinant, and this comes from the data classification and the quantity of data involved. Information criticality is defined as the relative importance of specific information to the business. Information criticality is a key measure used in the prioritization of actions throughout the incident response process. The loss of one administrator password is less serious than the loss of all of them. The second major element involves a business decision on how this incident plays into current business operations. A series of breaches, whether minor or not, indicates a pattern that can have public relations and regulatory issues.

Once an incident happens, it is time to react, and proper reaction requires a game plan. Contrary to what many want to believe, there are no magic silver bullets to kill the security demons. A solid, well-rehearsed incident response plan is required. This plan is custom-tailored to the information criticalities, the actual hardware and software architectures, and the people. Like all large, complex projects, the challenges rapidly become organizational in nature—budget, manpower, resources, and commitment.

CERT is a trademark of Carnegie Mellon and is frequently used in some situations, such as the US-CERT.

Incident Management

Having an incident response management methodology is a key risk mitigation strategy. One of the steps that should be taken to establish a plan to handle business interruptions as a result of a cyber event of some sort is the establishment of a computer incident response team (CIRT) or a computer emergency response team (CERT).

The organization’s CIRT will conduct the investigation into the incident and make the recommendations on how to proceed. The CIRT should consist of not only permanent members but also ad hoc members who may be called upon to address special needs depending on the nature of the incident. In addition to individuals with a technical background, the CIRT should include nontechnical personnel to provide guidance on ways to handle media attention, legal issues that may arise, and management issues regarding the continued operation of the organization. The CIRT should be created, and team members should be identified before an incident occurs. Policies and procedures for conducting an investigation should also be worked out in advance of an incident occurring. It is also advisable to have the team periodically meet to review these procedures.

Goals of Incident Response

The goals of an incident response process are multidimensional in nature.

![]() Confirm or dispel incident

Confirm or dispel incident

![]() Promote accurate information accumulation and dissemination

Promote accurate information accumulation and dissemination

![]() Establish controls for evidence

Establish controls for evidence

![]() Protect privacy rights

Protect privacy rights

![]() Minimize disruption to operations

Minimize disruption to operations

![]() Allow for legal/civil recourse

Allow for legal/civil recourse

![]() Provide accurate reports/recommendations

Provide accurate reports/recommendations

Incident response depends upon accurate information. Without it, the chance of following data in the wrong direction is a possibility, as is missing crucial information and only finding dead ends. The preceding goals are essential for the viability of an incident response process and the desired outcomes.

Anatomy of an Attack

Attackers have a method by which they attack a system. Although the specifics may differ from event to event, there are some common steps that are commonly employed. There are numerous types of attacks, from old-school hacking to the new advanced persistent threat (APT) attack. The differences are subtle and are related to the objectives of each form of attack.

Using nmap to Fingerprint an Operating System

To use nmap to fingerprint an operating system, use the –O option:

nmap -O –v

scanme.nmap.org

This command performs a scan of interesting ports on the target (scanme.nmap.org) and attempts to identify the operating system. The –v option indicates that you want verbose output.

Old School

Attacks are not a new phenomenon in enterprise security, and a historical examination of large numbers of attacks shows some common methods. These are the traditional steps:

1. Footprinting

2. Scanning

3. Enumeration

4. Gain access

5. Escalate privilege

6. Pilfer

7. Create backdoors

8. Cover tracks

9. Denial of service (DOS)

Footprinting is the determination of the boundaries of a target space. There are numerous sources of information, including web sites, DNS records, and IP address registrations. Understanding the boundaries assists an attacker in knowing what is in their target range and what isn’t. Scanning is the examination of machines to determine what operating systems, services, and vulnerabilities exist. The enumeration step is a listing of the systems and vulnerabilities to build an attack game plan. The first actual incursion is gaining access to an account on the system, almost always an ordinary user, as higher-privilege accounts are harder to target.

The next step is to gain access to a higher-privilege account by escalating privileges. From a higher-privilege account, the range of accessible activities is greater, including pilfering files, creating backdoors so you can return, and covering your tracks by erasing logs. The detail associated with each step may vary from hack to hack, but in most cases, these steps are employed in this manner to achieve an objective.

Advanced Persistent Threat

A relatively new attack phenomenon is the advanced persistent threat (APT), which is an attack that always maintains a primary focus on remaining in the network, operating undetected, and having multiple ways in and out. APTs began with nation-state attackers, but the utility of the long-term attack has proven valuable, and many sophisticated attacks have moved to this route. Most APTs begin via a phishing or spear phishing attack, which establishes a foothold in the system under attack. From this foothold, the attack methodology is similar to the traditional attack method described in the previous section, but additional emphasis is placed on the steps needed to maintain a presence on a network, as shown here:

1. Define target

2. Research target

3. Select tools

4. Test for detection

5. Initial intrusion

6. Establish outbound connection

7. Obtain credentials

8. Expand access

9. Strengthen foothold

10. Cover tracks

11. Exfiltrate data

The initial intrusion is usually performed via social engineering (spear phishing), over e-mail, using zero-day custom malware. Another popular infection method is the use of a watering hole attack, planting the malware on a web site that the victim employees will likely visit. The use of custom malware makes detecting the attack by antivirus/malware programs a near impossibility. After the attackers gain access, they attempt to expand access and strengthen the foothold. This is done by planting remote administration Trojan (RAT) software in the victim’s network, creating network backdoors and tunnels that allow stealth access to its infrastructure.

The next step, obtaining credentials and escalating privileges, is performed through the use of exploits and password cracking. The true objective is to acquire administrator privileges over a victim’s computer and ultimately expand it to Windows domain administrator accounts. One of the hallmarks of an APT attack is the emphasis on maintaining a presence on the system to ensure continued control over access channels and credentials acquired in previous steps. A common technique used is lateral movement across a network. Moving laterally allows an attacker to expand control to other workstations, servers, and infrastructure elements and perform data harvesting on them. Attackers also perform internal reconnaissance, collecting information on surrounding infrastructure, trust relationships, and information concerning the Windows domain structure.

APT Attack Model

The computer security investigative firm Mandiant (now a division of FireEye) was one of the pioneers in the use of incident response techniques against APTstyle attacks. They published a model of an APT attack to use as a guide, listed here:

1. Initial compromise

2. Establish foothold

3. Escalate privileges

4. Internal reconnaissance

5. Move laterally

6. Maintain presence

7. Complete mission

The key step is step 5, moving laterally. Lateral movement is where the adversary traverses your network, using multiple accounts, and does so to discover material worth stealing as well as to avoid being locked out by normal operational changes. This is one element that can be leveraged to help slow down, detect, and defeat APT attacks. Blocking lateral movement can defeat APT-style attacks from spreading through a network and can limit their stealth.

Cyber Kill Chain

A modern cyberattack is a complex, multistage process. The concept of a kill chain is the targeting of specific steps of a multistep process with the goal of disrupting the overall process. The term cyber kill chain is the application of this philosophy to a cyber incident, with the expressed purpose of disrupting the attack.

Taking the information already presented, you know the steps that hackers take and you have indicators that can clue you in to the current status of an attack. Using this information, you can plan specific interventions to each step of the attacker’s process. The strength of the kill chain is that it provides insight into where you can potentially see an attacker and gives defenders opportunities to stop an attack before it gets to the dangerous portion, where hostile actions occur.

• Figure 22.1 Cyber kill chain

Threat Intelligence

A second major tool for defenders who are hunting attackers is threat intelligence. As presented in Chapter 1, threat intelligence is the actionable information about malicious actors, their tools, infrastructure, and methods. Incident response is a game of resource management. No firm has the resources to protect everything against all threats or investigate all possible hostile actions; attempting to do so would result in wasted efforts. A key decision is where to apply incident response resources in response to an incident. A combination of threat intelligence combined with the concept of the kill chain (the attacker’s most likely path) and you have a means to prioritize actions against most meaningful threats.

Threat intelligence and open source intelligence were covered in Chapter 1. You can find more details in that chapter.

Incident Response Defined

NIST Special Publication 800-61 defines an incident as the act of violating an explicit or implied security policy. This violation can be intentional, incidental, or accidental, with causes being wide and varied in nature. These include but are not limited to the following:

![]() Attempts (either failed or successful) to gain unauthorized access to a system or its data

Attempts (either failed or successful) to gain unauthorized access to a system or its data

![]() Unwanted disruption or denial of service

Unwanted disruption or denial of service

![]() The unauthorized use of a system for the processing or storage of data

The unauthorized use of a system for the processing or storage of data

![]() Changes to system hardware, firmware, or software characteristics without the owner’s knowledge, instruction, or consent

Changes to system hardware, firmware, or software characteristics without the owner’s knowledge, instruction, or consent

![]() Environmental changes that result in data loss or destruction

Environmental changes that result in data loss or destruction

![]() Accidental actions that result in data loss or destruction

Accidental actions that result in data loss or destruction

Incident Response Process

Incident Response Process

Incident response is the set of actions security personnel perform in response to a wide range of triggering events. These actions are vast and varied because they have to deal with a wide range of causes and consequences. Through the use of a structured framework, coupled with properly prepared processes, incident response becomes a manageable task. Without proper preparation, this task can quickly become impossible or intractably expensive.

Incident response is the new business cultural norm in information security. The key is to design the procedures to include appropriate business personnel, not keep it as a pure information security endeavor. The challenges are many, including the aspect of timing as the activities quickly become a case of one group of professionals pursuing another.

Incident response is a multistep process with several component elements. The first is organization preparation, followed by system preparation. An initial detection is followed by initial response and then isolation, investigation, recovery, and reporting. There are additional process steps of follow-up and lessons learned, each of which is presented in following sections. Incident response is a key element of a security posture and must involve many different aspects of the business to properly respond. This is best built upon the foundation of a comprehensive incident response policy that details the roles and responsibilities of the organizational elements with respect to the process elements detailed in this chapter.

For the elements of incident response process, it is important to know the names, the topics contained, and the order in which they are performed as any of these concepts can be on the exam. The steps are as follows: preparation, identification, containment, eradication, recovery, and lessons learned.

Incident response activities at times are closely related to other IT activities involving IT operations. Incident response activities can be similar to disaster recovery and business continuity operations. Incident response activities are not performed in a vacuum but rather are intimately connected to many operational procedures, and this connection is key to overall system efficiency.

Preparation

Preparation is the phase of incident response that occurs before a specific incident. Preparation includes all the tasks needed to be organized and ready to respond to an incident. Incident response is the set of actions security personnel perform in response to a wide range of triggering events. These actions are wide and varied, as they have to deal with a wide range of causes and consequences. The organization needs to establish the steps to be taken when an incident is discovered (or suspected); determine points of contact; train all employees and security professionals so they understand the steps to take and who to call; establish an incident response team; acquire the equipment necessary to detect, contain, and recover from an incident; establish the procedures and guidelines for the use of the equipment obtained; and train those who will use the equipment. Through the use of a structured framework coupled with properly prepared processes, incident response becomes a manageable task. Without proper preparation, this task can quickly become impossible or intractably expensive. Successful handling of an incident is a direct result of proper preparation.

The old adage that “those who fail to prepare, prepare to fail” certainly applies to incident response. Without preparation, an organization’s response to a security incident will be haphazard and ineffective. Establishing the processes and procedures to follow in advance of an event is critical.

Organization Preparation

Preparing an organization requires an incident response plan, both for the initial effort and for the maintenance of that effort. Over time, the organization shifts based on business objectives, personnel change, business efforts and focus change, new programs, and new capabilities; virtually any change can necessitate shifts in the incident response activities. At a minimum, the following items should be addressed and periodically reviewed in terms of incident response preparation:

![]() Develop and maintain comprehensive incident response policies and procedures

Develop and maintain comprehensive incident response policies and procedures

![]() Establish and maintain an incident response team

Establish and maintain an incident response team

![]() Obtain top-level management support

Obtain top-level management support

![]() Agree to ground rules/rules of engagement

Agree to ground rules/rules of engagement

![]() Develop scenarios and responses

Develop scenarios and responses

![]() Develop and maintain an incident response toolkit

Develop and maintain an incident response toolkit

![]() System plans and diagrams

System plans and diagrams

![]() Network architectures

Network architectures

![]() Critical asset lists

Critical asset lists

![]() Practice response procedures

Practice response procedures

![]() Fire drills

Fire drills

![]() Scenarios (“Who do you call?”)

Scenarios (“Who do you call?”)

System Preparation

Systems require preparation for effective incident response efforts. Incident responders are dependent upon documentation for understanding hardware, software, and network layouts. Understanding how access control is employed, including specifics across all systems, is key when determining who can do what—a common incident response question. Understanding the logging methodology and architecture will make incident response data retrieval easier. All of these questions should be addressed in planning of diagrams, access control, and logging, to ensure that these critical security elements are capturing the correct information before an incident.

Having lists of critical files and their hash values, all stored offline, can make system investigation a more efficient process. In the end, when architecting a system, taking the time to plan for incident response processes will be crucial to a successful response once an incident occurs. Preparing systems for incident response is similar to preparing them for maintainability, so these efforts can yield regular dividends to the system owners. Determining the steps to isolate specific machines and services can be a complex endeavor and is one best accomplished before an incident, through the preparation phase.

Preparing for Incident Detection

To ensure that discovering incidents is not an ad hoc, hit-or-miss proposition, the organization needs to establish procedures that describe the process administrators must follow to monitor for possible security events. The tools for accomplishing this task are identified during the preparation phase, as well as any required training. The procedures governing the monitoring tools used should be established as part of the specific guidelines governing the use of the tools but should include references to the incident response policy.

Researching Vulnerabilities

After the hacker has a list of software running on the systems, he will start researching the Internet for vulnerabilities associated with that software. Numerous web sites provide information on vulnerabilities in specific programs and operating systems. Understanding how hackers navigate systems is important because system administrators and security personnel can use the same steps to research potential vulnerabilities before a hacker strikes. This information is valuable to administrators who need to know what problems exist and how to patch them.

Incident Response Team

Establishing an incident response team is an essential step in the preparation phase. Although the initial response to an incident may be handled by an individual, such as a system administrator, the complete handling of an incident typically takes an entire team. An incident response team is a group of people who prepare for and respond to any emergency incident, such as a natural disaster or an interruption of business operations. A computer security incident response team in an organization typically includes key skilled members who bring a wide range of skills to bear in the response effort. Incident response teams are common in corporations as well as in public service organizations.

Incident response team members ideally are trained and prepared to fulfill the roles required by the specific situation (for example, to serve as incident commander in the event of a large-scale public emergency). Incident response teams are frequently dynamically sized to the scale and nature of an incident, and as the size of an incident grows and as more resources are drawn into the event, the command of the situation may shift through several phases. In a small-scale event, or in the case of a small firm, usually only a volunteer or ad hoc team may exist to respond. In cases where the incident spreads beyond the local control of the incident response team, higher-level resources through industry groups and government groups exist to assist in the incident. Advanced preparation in the form of contacting and establishing working relations with higher-level groups is an important preparation step.

Incident Response Team Questions

Well-executed plans are often well tested; when and how often do you test your response plans? How will your team operate undetected in an environment owned by the adversary? Do you have a backup, separate e-mail system that is external to the enterprise solution? Is it encrypted?

The incident response team is a critical part of the incident response plan. Team membership will vary depending on the type of incident or suspected incident but may include the following members:

![]() Team lead

Team lead

![]() Network/security analyst

Network/security analyst

![]() Internal and external subject-matter experts

Internal and external subject-matter experts

![]() Legal counsel

Legal counsel

![]() Public affairs officer

Public affairs officer

![]() Security office contact

Security office contact

In determining the specific makeup of the team for a specific incident, there are some general points to think about. The team needs a leader, preferably a higher-level manager who has the ability to obtain cooperation from employees as needed. It also needs a computer or network security analyst, since the assumption is that the team will be responding to a computer security incident. Specialists may be added to the team for specific hardware or software platforms as needed. The organization’s legal counsel should be part of the team on at least a part-time or as-needed basis. The public affairs office should also be available on an as-needed basis, because it is responsible for formulating the public response should a security incident become public. The organization’s security office should also be kept informed. It should designate a point of contact for the team in case criminal activity is suspected. In this case, care must be taken to preserve evidence should the organization decide to push for prosecution of the individuals.

This is by no means a complete list because each organization is different and needs to evaluate what the best mixture is for its own response team. Whatever the decision, the composition of the team, and how and when it will be formed, needs to be clearly addressed in the preparation phase of the incident response policy.

To function in a timely and efficient manner, ideally a team has already defined a protocol or set of actions to perform to mitigate the negative effects of most common forms of an incident. One key and often overlooked member of the incident response team is the business. It may be an IT system being investigated, but the data, processes, and value all belong to the business, and the business is the element that understands the risk and value of what is under attack. Having key, knowledgeable business members on the incident response team is a necessity to ensure that the security actions remain aligned with the business goals and objectives of the organization.

Incident Response Plan

An incident response plan is documentation associated with the steps an organization performs in response to any situation determined to be abnormal in the operation of a computer system. The value of the plan lies in its ability to facilitate execution of the required response steps. Although individual causes may vary, there is a defined response methodology in the plan, and this guides responders to the correct actions. A well-documented and approved plan also assists in providing the necessary management permissions in advance as opposed to lengthy decision cycles when the heat of an attack is on.

Two major elements play a role in determining the level of response. Information criticality is the primary determinant, and this comes from the data classification and the quantity of data involved. The loss of one administrator password is less serious than the loss of all of them, for example. The second factor involves a business decision on how this incident plays into current business operations. A series of breaches, whether minor or not, indicates a pattern that can have public relations and regulatory issues.

Documented Incident Types/Category Definitions

To assist in the planning of responses and to group the myriad possible incidents into a manageable set of categories, one step of the incident response planning process is to define incident types/categories. Documented incident types/category definitions provide planners and responders with a set number of preplanned scripts that can be applied quickly, minimizing repetitive approvals and process flows. Examples of categories are interruption of a service, malicious communication, data exfiltration, malware delivery, phishing attack, and so on. This list should be customized to meet the IT needs of each firm.

Roles and Responsibilities

It’s critical to define the roles and responsibilities of the incident response team members. These roles and responsibilities may vary slightly based on the identified categories, but defining them before an incident occurs empowers the team to perform the necessary tasks during the time-sensitive aspects of an incident. Permissions to cut connections, change servers, or start/stop services are common examples of predefined actions that are best defined in advance to prevent time-consuming approvals during an actual incident.

Reporting Requirements/Escalation

Planning the desired reporting requirements including escalation steps is an important part of the operational plan for an incident. Who will speak about the incident and to whom? How does the information flow? Who needs to be involved? When does the issue escalate to higher levels of management? These are all questions best handled in the calm of a pre-incident planning meeting where the procedures are crafted rather than on the fly as an incident is occurring.

Cyber-Incident Response Teams

Typically more than one person will respond to an incident. Defining the cyber-incident response team, including identifying key membership and backup members, is a task that needs to be done prior to an incident occurring. Once a response begins, trying to find personnel to do tasks only slows down the function and in many cases makes it unmanageable. The planning aspect of incident response needs to define who is on the team, whether a dedicated team or a group of situational volunteers, and what their duties are.

Exercise

You don’t really know how well a plan is crafted until it is tested. Exercises come in many forms and functions, and doing a tabletop exercise where planning and preparation steps are tested is an important final step in the planning process.

Incident Identification/Detection

An incident is defined as a situation that departs from normal, routine operations. What differentiates an incident from an incident that requires a formal response from the incident response team is an important triage step performed at the beginning of the discovery of an abnormal condition. A single failed login is technically an incident, but if it is followed by a correct login, then it is not of any consequence. In fact, this could even be considered as normal. But 10,000 failed attempts on a system, or failures across a large number of accounts, are distinctly different and may be worthy of further investigation.

Detection

Of course, an incident response team can’t begin an investigation until a suspected incident has been detected. At that point, the detection phase of the incident response policy kicks in. One of the first jobs of the incident response team is to determine whether an actual security incident has occurred. Many things can be misinterpreted as a possible security incident. For example, a software bug in an application may cause a user to lose a file, and the user may blame this on a virus or similar malicious software. The incident response team must investigate each reported incident and treat it as a potential security incident until it can determine whether it is or isn’t. This means that your organization will want to respond initially with a limited response team before wasting a lot of time having the full team respond. This is the initial step to take when a report is received that a possible incident has been detected.

Security incidents can take a variety of forms, and who discovers the incident will vary as well. One of the groups most likely to discover an incident is the team of network and security administrators that runs devices such as the organization’s firewalls and intrusion detection systems.

Detecting that a security event is occurring or has occurred is not necessarily an easy matter. In certain situations, such as the activation of a malicious payload for a virus or worm that deletes critical files, it will be obvious that an event has occurred. In other situations, such as where an individual has penetrated your system and has been slowly copying critical files without changing or destroying anything, the event may take a lot longer to detect. Often, the first indication that a security event has occurred might be a user or administrator noticing that something is “funny” about the system or its response.

Another common incident is a virus. Several packages are available that can help an organization detect potential virus activity or other malicious code. Administrators will often be the ones to notice something is amiss, but so might an average user who has been hit by the virus.

Social engineering is a common technique used by potential intruders to acquire information that may be useful in gaining access to computer systems, networks, or the physical facilities that house them. Anybody in the organization can be the target of a social engineering attack, so all employees need to know what to be looking for regarding this type of attack. In fact, the target might not even be one of your organization’s employees—it could be a contractor, such as somebody on the custodial staff or nighttime security staff. Whatever the type of security incident suspected, and no matter who suspects it, a reporting procedure needs to be in place for the employees to use when an incident is detected. Everybody needs to know who to call should they suspect something, and everybody needs to know what to do. A common technique is to develop a reporting template that can be supplied to an individual who suspects an incident so that the necessary information is gathered in a timely manner.

Identification

As discussed previously, an incident is defined as any situation that departs from normal, routine operations. Whether an incident is important or not is the first point of decision as part of an incident response process. The act of identification is coming to a decision that the information related to the incident is worthy of further investigation by the IR team and, in addition, what aspects of the IR team are needed to respond. An e-mail incident may require different response team members than an attack on web services or Active Directory.

A key first step is in the processing of information and the determination of whether to invoke incident response processes. Incident information can come from a wide range of sources, including logs, employees, help desk calls, system monitoring, security devices, and more. The challenge is to detect that something other than simple common errors that are routine is occurring. When evidence accumulates, or in some cases specific items such as security device logs indicate a potential incident, the next step is to escalate the situation to the incident response team.

Initial Response Errors

Mistakes such as these are common during initial response:

![]() Failure to document findings appropriately

Failure to document findings appropriately

![]() Failure to notify or provide accurate information to decision-makers

Failure to notify or provide accurate information to decision-makers

![]() Failure to record and control access to digital evidence

Failure to record and control access to digital evidence

![]() Waiting too long before reporting

Waiting too long before reporting

![]() Underestimating the scope of evidence that may be found

Underestimating the scope of evidence that may be found

Initial Response

Although there is no such thing as a typical incident, for any incident there is a series of questions that can be answered to form a proper initial response. Regardless of the source, the following items are important to determine during an initial response:

![]() Current time and date

Current time and date

![]() Who/what is reporting the incident

Who/what is reporting the incident

![]() Nature of the incident

Nature of the incident

![]() When the incident occurred

When the incident occurred

![]() Hardware/software involved

Hardware/software involved

![]() Point of contact for involved personnel

Point of contact for involved personnel

The purpose of an initial response is to begin the incident response action and place it on a proper pathway toward success. The initial response must support the goals of the information security program. If something is critical, treating it as routine would be a mistake, so triage with respect to information criticality is important. The initial response must also be aligned with the business practices and objectives. Triage with respect to current business imperatives and conditions is important. The initial response actions need to be designed to comply with administrative and legal policies as well as to support decisions with regard to civil, administrative, or criminal investigations/actions. For these purposes, maintaining a forensically sound process from the beginning is important. It is also important that the information is delivered accurately and expeditiously to the appropriate decision-makers so that future actions can be timely. One of the greatest tools to achieve all of these goals is a simple and efficient process, so establishing fewer steps that are clear and clean is preferred. Complexity in the initial response process only leads to issues later because of delays, confusion, and incomplete information.

First Responder

A cyber first responder must do as much as possible to control damage or loss of evidence. Obviously, as time passes, evidence can be tampered with or destroyed. Look around on the desk, on the Rolodex, under the keyboard, in desktop storage areas, and on cubicle bulletin boards for any information that might be relevant. Secure floppy disks, optical discs, flash memory cards, USB drives, tapes, and other removable media. Request copies of logs as soon as possible. Most ISPs will protect logs that could be subpoenaed. Take photos (some localities require the use of Polaroid photos because they are more difficult to modify without obvious tampering) or video. Include photos of operating computer screens and hardware components from multiple angles. Be sure to photograph internal components before removing them for analysis. The first responder can do much to prevent damage or can cause significant loss by digitally altering evidence, even inadvertently. Collecting data should be done in a forensically sound nature (see Chapter 23 for details), and be sure to pay attention to recording time values so time offsets can be calculated.

Common Technical Errors

Common technical mistakes during initial response include the following:

![]() Altering time/date stamps on evidence systems

Altering time/date stamps on evidence systems

![]() “Killing” rogue processes

“Killing” rogue processes

![]() Patching the system

Patching the system

![]() Not recording the steps taken on the system

Not recording the steps taken on the system

![]() Not acting passively

Not acting passively

Containment/Incident Isolation

Once the incident response team has determined that an incident has occurred and requires a response, the first step is to contain the incident and prevent it from spreading. If this is a virus or worm that is attacking database servers, then the protection of uninfected servers is paramount. Containment is the set of actions that are taken to constrain the incident to the minimal number of machines. This preserves as much of production as possible and ultimately makes handling the incident easier. This can be complex because in many cases to contain the problem, one has to fully understand the problem, its root cause, and the vulnerabilities involved.

Containment and Eradication

Once the incident response team has determined that an incident most likely has occurred, it must attempt to quickly contain the problem. At this point or soon after containment begins, depending on the severity of the incident, management needs to decide whether the organization intends to prosecute the individual who has caused the incident (in which case collection and preservation of evidence is necessary) or simply wants to restore operations as quickly as possible without regard to possibly destroying evidence. In certain circumstances, management might not have a choice, such as if specific regulations or laws require it to report particular incidents. If management makes the decision to prosecute, specific procedures need to be followed in handling potential evidence. Individuals trained in forensics should be used in this case.

The incident response team must decide how to address containment as soon as it has determined that an actual incident has occurred. If an intruder is still connected to the organization’s system, one response is to disconnect from the Internet until the system can be restored and vulnerabilities can be patched. This, however, means that your organization is not accessible to customers over the Internet during that time, which may result in lost revenue. Another response might be to stay connected and attempt to determine the origin of the intruder. A decision will need to be made as to which is more important for your organization. Your incident response policy should identify who is authorized to make this decision.

Other possible containment activities might include adding filtering rules or modifying existing rules on firewalls, routers, and intrusion detection systems; updating antivirus software; and removing specific pieces of hardware or halting specific software applications. If an intruder has gained access through a specific account, disabling or removing that account may also be necessary.

Qakbot Worm Isolation

The following are summary notes made by a firm that was hit by the Qakbot worm. Consider how your incident response process would respond to this scenario.

![]() Laptop infected while off network

Laptop infected while off network

![]() When rejoined company network

When rejoined company network

![]() Spread to open network drives within minutes

Spread to open network drives within minutes

![]() Spread to a group of computers within 60 minutes using a common administrator credential

Spread to a group of computers within 60 minutes using a common administrator credential

![]() Infection identified by server antivirus detecting dropped files

Infection identified by server antivirus detecting dropped files

![]() Malware analysis identified command and control connections

Malware analysis identified command and control connections

![]() Identified additional infected systems from network logs

Identified additional infected systems from network logs

![]() Could not immediately take infected computers out of service because they were being used in a critical function

Could not immediately take infected computers out of service because they were being used in a critical function

![]() Computers were also geographically dispersed

Computers were also geographically dispersed

![]() Had to isolate a portion of the network (while still allowing critical data flows) while remediating one computer at a time during a maintenance window

Had to isolate a portion of the network (while still allowing critical data flows) while remediating one computer at a time during a maintenance window

Although Qakbot may not be a threat to your network, similar threats abound, and the response measures will be similar.

Once the immediate problems have been contained, the incident response team needs to address the cause of the incident. If the incident is the result of a vulnerability that was not patched, the patch must be obtained, tested, and applied. Accounts may need to be disabled or passwords may need to be changed. Complete reloading of the operating system might be necessary if the intruder has been in the system for an unknown length of time or has modified system files. Determining when an intruder first gained access to your system or network is critical in determining how far back to go in restoring the system or network.

Quarantine

One method of isolating a machine is through a quarantine process. Quarantine is a process of isolating an object from its surroundings, preventing normal access methods. The machine may be allowed to run, but its connection to other machines is broken in a manner to prevent the spread of infection. Quarantine can be accomplished through a variety of mechanisms, including the erection of firewalls restricting communication between machines. This can be a fairly complex process, but if properly configured in advance, the limitations of the quarantine operation can allow the machine to continue to run for diagnostic purposes, even if it no longer processes a workload.

Device Removal

A more extreme response is device removal. In the event that a machine becomes compromised, it is simply removed from production and replaced. When device removal entails the physical change of hardware, this is a resource-intensive operation. The reimaging of a machine can be a time-consuming and difficult endeavor. The advent of virtual machines changes this entirely, as the provisioning of virtual images on hardware can be accomplished in a much quicker fashion.

Escalation and Notification

One key decision point in initial response is that of escalation. When a threshold of information becomes known to an operator and the operator decides to escalate the situation, the incident response process moves to a notification and escalation phase. Not all incidents are of the same risk profile, and incident response efforts should map to the actual risk level associated with the incident. When the incident response team is notified of a potential incident, its first steps are to confirm the existence, scope, and magnitude of the event and then respond accordingly. This is typically done through a two-step escalation process, where a minimal quick-response team begins and then adds members as necessitated by the issue.

Assessing the risk associated with an incident is an important first step. If the characteristics of an incident include a large number of packets destined for different services on a machine (an attack commonly referred to as a port scan), then the actions needed are different from those needed to respond to a large number of packets destined to a single machine service. Port scans are common, and to a degree relatively harmless, while port flooding can result in denial of service. Determining the specific downstream risks is important in prioritizing response actions.

Strategy Formulation

The response to an incident will be highly dependent upon the particular circumstances of the intrusion. There are many paths one can take in the steps associated with an incident; the challenge is in choosing the best steps in each case. During the preparation stage, a wide range of scenarios can be examined, allowing time to formulate strategies. Even after an incident response team has planned a series of strategies to respond to various scenarios, determining how to employ those preplanned strategies to proper effect still depends on the circumstances of a particular incident. A variety of factors should be considered in the planning and deployment of strategies, including, but not limited to, the following:

![]() How critical are the impacted systems?

How critical are the impacted systems?

![]() How sensitive is the data?

How sensitive is the data?

![]() What is the potential overall dollar loss involved/rate of loss?

What is the potential overall dollar loss involved/rate of loss?

![]() How much downtime can be tolerated?

How much downtime can be tolerated?

![]() Who are the perpetrators?

Who are the perpetrators?

![]() What is the skill level of the attacker?

What is the skill level of the attacker?

![]() Does the incident have adverse publicity potential?

Does the incident have adverse publicity potential?

These pieces of information provide boundaries for the upcoming investigations. There are still numerous issues that need to be determined with respect to the upcoming investigation. Addressing these issues helps provide focal points during the investigation.

![]() Restore normal operations

Restore normal operations

![]() Offline recovery?

Offline recovery?

![]() Online recovery?

Online recovery?

![]() Determine public relations play

Determine public relations play

![]() “To spin or not to spin?”

“To spin or not to spin?”

![]() Determine probable attacker

Determine probable attacker

![]() Internal: handle internally or prosecute?

Internal: handle internally or prosecute?

![]() External: prosecute?

External: prosecute?

![]() Involve law enforcement?

Involve law enforcement?

![]() Determine type of attack

Determine type of attack

![]() DoS, theft, vandalism, policy violation?

DoS, theft, vandalism, policy violation?

![]() Ongoing intrusion?

Ongoing intrusion?

![]() Pivoting?

Pivoting?

![]() Classify victim system

Classify victim system

![]() Critical server/application?

Critical server/application?

![]() Number of users?

Number of users?

![]() What other systems are affected?

What other systems are affected?

Investigation Best Practice

The first rule of incident response investigations is “Do no harm.” If the investigation itself causes issues for the business, how is this different from a business perspective than the original attack vector? In fact, in advanced threats, the attackers take great care not to impact the system or business operations in any way that could lead to their discovery. It is important for the response team to exercise extreme caution and to do no harm, lest they make future investigations impractical or deemed to be not worth pursuing.

Using the answers to these questions helps the team determine the necessary steps in the upcoming investigation phase. Although it is impossible to account for all circumstances, this level of strategy can greatly assist in scoping the work ahead during the investigation phase.

Investigation

The true investigation phase of an incident is a multistep, multiparty event. With the exception of very simple events, most incidents will involve multiple machines and potentially impact the business in multiple ways.

The primary objective of the investigative phase is to make the following determinations:

![]() What happened

What happened

![]() What systems are affected

What systems are affected

![]() What was compromised

What was compromised

![]() What was the vulnerability

What was the vulnerability

![]() Who did it (if possible to determine)

Who did it (if possible to determine)

![]() What are the recovery/remediation options

What are the recovery/remediation options

Looking at the list, it is daunting, but this is where the real work of incident response occurs. It will take a team effort, partly because of workload, partly because of specialized skills, and partly because the entire effort is being performed in a race against time.

Duplication

Duplication of drives is a common forensics process. It is important to have accurate copies and proper hash values so that any analysis is performed under proper conditions. Proper disk duplication is necessary to ensure all data, including metadata, is properly captured and analyzed as part of the overall process.

NetFlow Data

A flow is unidirectional, so bidirectional flow would be recorded as two separate flows. NetFlow data is defined by these seven unique keys:

![]() Source IP address

Source IP address

![]() Destination IP address

Destination IP address

![]() Source port

Source port

![]() Destination port

Destination port

![]() Layer 3 protocol

Layer 3 protocol

![]() TOS byte (DSCP)

TOS byte (DSCP)

![]() Input interface (ifIndex)

Input interface (ifIndex)

Network Monitoring

To monitor network flow data, including who is talking to whom, one source of information is NetFlow data. NetFlow is a protocol/standard for the collection of network metadata on the flows of network traffic. NetFlow is now an IETF standard and allows for unidirectional captures of communication metadata. NetFlow can identify both common and unique data flows, and in the case of incident response, typically the new and unique NetFlow patterns are of most interest to incident responders.

Eradication

Once a problem has been contained to a set footprint, the next step is eradication. Eradication involves removing the problem, and in today’s complex system environment, this may mean rebuilding a clean machine. A key part of operational eradication is the prevention of reinfection. Presumably, the system that existed before the problem occurred would be prone to a repeat infection, and thus this needs to be specifically guarded against. One of the strongest value propositions for virtual machines is the ability to rebuild quickly, making the eradication step relatively easy.

Recovery

After the issue has been eradicated, the recovery process begins. At this point, the investigation is complete and documented. Recovery is the returning of the asset into the business function. Eradication, the previous step, removed the problem, but in most cases the eradicated system will be isolated. The recovery process includes the steps necessary to return the systems and applications to operational status.

Recovery is an important step in all incidents. One of the first rules is to not trust a system that has been compromised, and this includes all aspects of an operating system. Whether there is known destruction or not, the safe path is one where the recovery step includes reconstruction of affected machines. Recovery efforts from an incident involve several specific elements. First, the cause of the incident needs to be determined and resolved. This is done through an incident response mechanism. Attempting to recover before the cause is known and corrected will commonly result in a continuation of the problem. Second, the data, if sensitive and subject to misuse, needs to be examined in the context of how it was lost, who would have access, and what business measures need to be taken to mitigate specific business damage as a result of the release. This may involve the changing of business plans if the release makes them suspect or subject to adverse impacts.

Recovery can be a two-step process. First, the essential business functions can be recovered, enabling business operations to resume. The second step is the complete restoration of all services and operations. Because of the difficulty and uncertainty involved in repairing systems, most best practices today involve reconstituting the underlying system and then transferring the operational data. Staging the recovery operations in a prioritized fashion allows a graceful return to an operating condition.

Restoration can be done in a wide variety of ways. For many systems, the reconstitution of a clean operating system can restore a system. This type of restoration requires a significant amount of preparation. Having a clean version of each of your assets provides for this type of restoration effort. Recovery sounds simple, but in large-scale incidents, the number of machines can be significant. Add to this the chance of reinfection as machines are restored. This means that simply replacing the machine with a clean machine is not sufficient, but rather the replacement needs protection against reinfection.

The other challenge in large-scale recovery events is the sequencing of the effort. When there are many machines to be restored and the restoration process takes time and resources, scheduling is essential. Setting up a prioritized schedule is one of the steps that needs to be considered in the planning process. The time to do this type of planning is before the hectic pace of an incident occurs.

There are many different incident response processes in the information security space. For the CompTIA Security+ exam, you should know the steps of their process:

![]() Preparation

Preparation

![]() Identification

Identification

![]() Containment

Containment

![]() Eradication

Eradication

![]() Recovery

Recovery

![]() Lessons learned

Lessons learned

A key aspect in many incidents is that of external communications. Having a communications expert who is familiar with dealing with the press and has the language nuances necessary to convey the correct information and not inflame the situation is essential to the success of any communication plan. Many firms attempt to use their legal counsel for this, but generally speaking, the legally precise language used by an attorney is not useful from a PR standpoint, and a more nuanced communicator may provide a better image. In many cases of crisis management, it is not the crisis that determines the final costs but the reaction to and communication of details after the initial crisis.

Reporting

After the system has been restored, the incident response team creates a report of the incident. Detailing what was discovered, how it was discovered, what was done, and the results, this report acts as a corporate memory and can be used for future incidents. Having a knowledge base of previous incidents and the actions used is a valuable resource because it is in the context of the particular enterprise. These reports also allow a mechanism to close the loop with management over the incident and, most importantly, provide a road map of the actions that can be used in the future to prevent events of identical or similar nature.

Part of the report will be recommendations, if appropriate, to change existing policies and procedures, including disaster recovery and business continuity. The similarity in objectives makes a natural overlap, and the cross-pollination between these operations is important to make all processes as efficient as possible.

Lessons Learned

A post-mortem session should collect lessons learned and assign action items to correct weaknesses and to suggest ways to improve. There is a famous quote about those who fail to learn from history are destined to repeat it. The lessons learned portion serves two distinct lesson sets. The first determines what went wrong and allowed the incident to occur in the first place. The second is that a failure to block this means a sure repeat.

Once the excitement of the incident is over and operations have been restored to their pre-incident state, it is time to take care of a few last items. Senior-level management must be informed about what occurred and what was done to address it. An after-action report should be created to outline what happened and how it was addressed. Recommendations for improving processes and policies should be incorporated so that a repeat incident will not occur. If prosecution of the individual responsible is desired, additional time will be spent helping law enforcement agencies and possibly testifying in court. Training material may also need to be developed or modified as part of the new or modified policies and procedures.

In the reporting process, a critical assessment of what went right, what went wrong, what can be improved, and what should be continued is prepared as a form of lessons learned. This is a critical part of self-improvement and is not meant to place blame but rather to assist in future prevention. Having things go wrong in a complex environment is part of normal operations; having repeat failures that are preventable is not. The key to the lessons learned section of the report is to make the necessary changes so that a repeat event will not occur. Because many incidents are a result of attackers using known methods, once the attack patterns are known in an enterprise and methods exist to mitigate them, then it is the task of the entire enterprise to take the necessary actions to mitigate future events.

Standards and Best Practices

Standards and Best Practices

There are many options available to a team when planning and performing processes and procedures. To assist the team in choosing a path, there are both standards and best practices to consult in the proper development of processes. From government sources to industry sources, there are many opportunities to gather ideas and methods, even from fellow firms.

State of Compromise

The new standard of information security involves living in a state of compromise, where you should always expect that adversaries are active in their networks. It is unrealistic to expect that you can keep attackers out of your network. Operating in a state of compromise does not mean that you must suffer significant losses. A working assumption when planning for, responding to, and managing the overall incident response process is that the systems are compromised and that prevention cannot be the only means of defense.

What Not to Do as Part of Incident Response

The U.S. Department of Justice has two specific recommended steps that you should not take as part of an incident response action.

![]() Do not use the compromised system to communicate.

Do not use the compromised system to communicate.

![]() Do not hack into or damage another network or system.

Do not hack into or damage another network or system.

The victim organization should always assume that any communications across affected machines will be compromised. This eavesdropping action is standard hacker behavior, and if you tip off your actions, they can be countered before you regain control of your system. Hacking, even retaliatory hacking, is illegal, and given the difficulty in attribution, attempts to respond by hacking the hacker may accidently result in hacking an innocent third-party machine.

NIST

The National Institute of Standards and Technology, a U.S. governmental entity under the Department of Commerce, produces a wide range of Special Publications (SPs) in the area of computer security. Grouped into several different categories, the most relevant SPs for incident response come from the Special Publications 800 series:

![]() Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, SP 800-61 Rev. 2

Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, SP 800-61 Rev. 2

![]() NIST Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP), SP 800-126 Rev 2

NIST Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP), SP 800-126 Rev 2

![]() Information Security Continuous Monitoring for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, SP 800-137

Information Security Continuous Monitoring for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, SP 800-137

![]() Guide to Selecting Information Technology Security Products, NIST SP 800-36

Guide to Selecting Information Technology Security Products, NIST SP 800-36

![]() Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies, NIST SP 800-40 Version 3

Guide to Enterprise Patch Management Technologies, NIST SP 800-40 Version 3

![]() Guide to Using Vulnerability Naming Schemes [CVE/CCE], NIST SP 800-51, Rev. 1

Guide to Using Vulnerability Naming Schemes [CVE/CCE], NIST SP 800-51, Rev. 1

Department of Justice

In April 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Cybersecurity Unit released a best practices document, Best Practices for Victim Response and Reporting of Cyber Incidents. This document identifies steps to take before a cyber incident, the steps to take during an incident response action, a list of actions to not take, and what to do after the incident. The URL for the document is in the “For More Information” section at the end of the chapter.

Indicators of Compromise

An indicator of compromise (IOC) is an artifact left behind from computer intrusion activity. Detecting IOCs is a quick way to jump-start a response element. Originated by the security firm Mandiant, IOCs have spread in usage to a wide range of firms. IOCs act as a tripwire for responders. An IOC can be tied to a specific observable event, which then can be traced to related events, and to stateful events such as Registry keys. One of the biggest challenges in incident response is getting on the trail of an attacker, and IOCs provide a means of getting on the trail.

Common Indicators of Compromise

These are common indicators of compromise:

![]() Unusual outbound traffic This probably is the clearest indicator that data is going where it shouldn’t.

Unusual outbound traffic This probably is the clearest indicator that data is going where it shouldn’t.

![]() Geographical irregularities Communications going to countries in which no business ties exist is another key indicator that data is going where it shouldn’t.

Geographical irregularities Communications going to countries in which no business ties exist is another key indicator that data is going where it shouldn’t.

![]() Unusual login activity Failed logins, login failures to nonexistent accounts, and so forth, indicate compromise.

Unusual login activity Failed logins, login failures to nonexistent accounts, and so forth, indicate compromise.

![]() Anomalous usage patterns for privileged accounts Changes in patterns of when administrators typically operate and what they typically access indicate compromise.

Anomalous usage patterns for privileged accounts Changes in patterns of when administrators typically operate and what they typically access indicate compromise.

![]() Changes in database access patterns This indicates hackers are searching for data or reading it to collect large quantities.

Changes in database access patterns This indicates hackers are searching for data or reading it to collect large quantities.

![]() Automated web traffic Timing can show some requests are scripts, not humans.

Automated web traffic Timing can show some requests are scripts, not humans.

![]() Change in HTML response sizes SQL injection can result in large HTML response sizes.

Change in HTML response sizes SQL injection can result in large HTML response sizes.

![]() Large numbers of requests for specific files Numerous requests for specific files, such as join.php, may indicate automated attack patterns.

Large numbers of requests for specific files Numerous requests for specific files, such as join.php, may indicate automated attack patterns.

![]() Mismatched port to application traffic This is a common method of attempting to hide activity.

Mismatched port to application traffic This is a common method of attempting to hide activity.

![]() Unusual DNS requests Command and control server traffic often use unusual DNS requests.

Unusual DNS requests Command and control server traffic often use unusual DNS requests.

![]() Unusual Registry changes Unusual changes are Indications of abnormal changes to a system state.

Unusual Registry changes Unusual changes are Indications of abnormal changes to a system state.

![]() Unexpected patching Some hackers/malware will patch to prevent other hackers from entering a target.

Unexpected patching Some hackers/malware will patch to prevent other hackers from entering a target.

![]() Bundles of data/files in wrong place Large aggregations of data, frequently encrypted, may be files being prepared for exfiltration.

Bundles of data/files in wrong place Large aggregations of data, frequently encrypted, may be files being prepared for exfiltration.

![]() Changes to mobile device profiles Mobile is the new perimeter, and changes may indicate malware.

Changes to mobile device profiles Mobile is the new perimeter, and changes may indicate malware.

![]() DDoS/DoS attacks Denial of service is used as a tool to provide smokescreen or distraction.

DDoS/DoS attacks Denial of service is used as a tool to provide smokescreen or distraction.

There are several standards associated with IOCs, but the three main ones are Cyber Observable eXpression (CybOX), a method of information sharing developed by MITRE; OpenIOC, an open source initiative established by Mandiant that is designed to facilitate rapid communication of specific threat information associated with known threats; and the Incident Object Description Exchange Format (IODEF), an XML format specified in RFC 5070 for conveying incident information between response teams, both internally and externally with respect to organizations. The “For More Information” section at the end of the chapter provides URLs for all three standards.

Security Measure Implementation

All data that is stored is subject to breach or compromise. Given this assumption, the question becomes, what is the best mitigation strategy to reduce the risk associated with breach or compromise? Data requires protection in each of the three states of the data life cycle: in storage, in transit, and during processing. The level of risk in each state differs because of several factors.

![]() Time Data tends to spend more time in storage and hence is subject to breach or compromise over longer time periods.

Time Data tends to spend more time in storage and hence is subject to breach or compromise over longer time periods.

![]() Quantity Data in storage tends to offer a greater quantity to breach or compromise than data in transit, and data in processing offers even less. If records are being compromised while being processed, then only records being processed are subjected to risk.

Quantity Data in storage tends to offer a greater quantity to breach or compromise than data in transit, and data in processing offers even less. If records are being compromised while being processed, then only records being processed are subjected to risk.

![]() Access Different protection mechanisms exist in each of the domains, and this has a direct effect on the risk associated with breach or compromise. Operating systems tend to have very tight controls to prevent cross-process data issues such as error and contamination.

Access Different protection mechanisms exist in each of the domains, and this has a direct effect on the risk associated with breach or compromise. Operating systems tend to have very tight controls to prevent cross-process data issues such as error and contamination.

The next aspect of risk during processing is within process access to the data, and a variety of attack techniques address this channel specifically. Data in transit is subject to breach or compromise from a variety of network-level attacks and vulnerabilities. Some of these are under the control of the enterprise, and some are not.

One primary mitigation step is data minimization. Data minimization efforts can play a key role in both operational efficiency and security. One of the first rules associated with data is this: Don’t keep what you don’t need. A simple example of this is the case of spam remediation. If spam is separated from e-mail before it hits a mailbox, one can assert that it is not mail and not subject to storage, backup, or data retention issues. As spam can comprise greater than 50 percent of incoming mail, spam remediation can dramatically improve operational efficiency in terms of both speed and cost.

This same principle holds true for other forms of information. When processing credit card transactions, certain data elements are required for the actual transaction, but once the transaction is approved, they have no further business value. Storing this information provides no business value, yet it does represent a risk in the case of a data breach. Data storage should be governed not by what you can store but by the business need to store. What is not stored is not subject to breach, and minimizing storage to only what is supported by the business need reduces risk and cost to the enterprise.

Minimization efforts begin before data even hits a system, let alone a breach. During system design, the appropriate security controls are determined and deployed, with periodic audits to ensure compliance. These controls are based on the sensitivity of the information being protected. One tool that can be used to assist in the selection of controls is a data classification scheme. Not all data is equally important, nor is it equally damaging in the event of loss. Developing and deploying a data classification scheme can assist in preventative planning efforts when designing security for data elements.

Data breaches may not be preventable, but they can be mitigated through minimization and encryption efforts.

Making Security Measurable

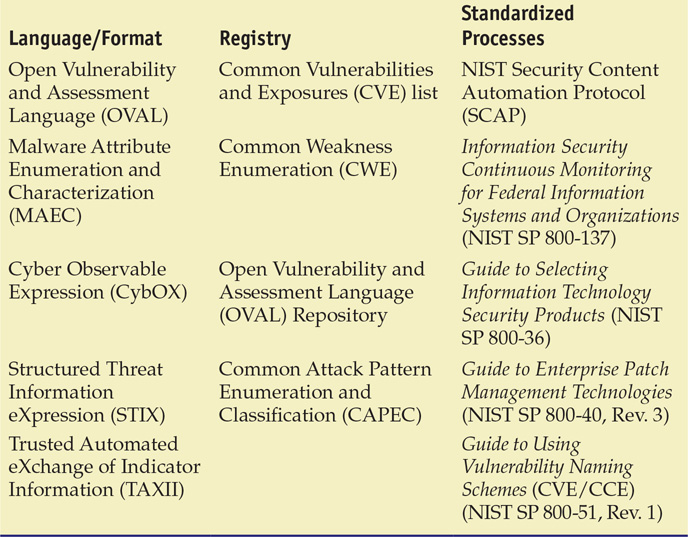

MITRE, working together with partners from government, industry, and academia, has created a set of techniques (called Making Security Measurable) to improve the measurability of security. This is a comprehensive effort, including registries of specific baseline data, standardized languages for the accurate communication of security information, and formats and standardized processes to facilitate accurate and timely communications.

The entirety of the project is beyond the scope of this text, but Table 22.1 lists some of the common items by category, a few of which are described next in a bit more detail.

Table 22.1 Sample Elements of Making Security Measurable

STIX and TAXII

MITRE has continued its efforts in the process of making security measurable and adding automation to the mix. Structured Threat Information eXpression (STIX) is a structured language for cyberthreat intelligence information. MITRE created Trusted Automated eXchange of Indicator Information (TAXII) as the main transport mechanism for cyberthreat information represented by STIX. TAXII services allow organizations to share cyberthreat information in a secure and automated manner.

CybOX

Cyber Observable eXpression (CybOX) is a standardized schema for the communication of observed data from the operational domain. Designed to streamline communications associated with incidents, CybOX provides a means of communicating key elements, including event management, incident management, and more, in an effort to improve interoperability, consistency, and efficiency.

For More Information

For More Information

CybOX https://cybox.mitre.org/

DOJ Best Practices for Victim Response and Reporting of Cyber Incidents www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/criminal-ccips/legacy/2015/04/30/04272015reporting-cyber-incidents-final.pdf

Incident Object Description Exchange Format (IODEF) https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5070

Making Security Measurable http://makingsecuritymeasurable.mitre.org/

Open IOC Framework www.openioc.org/

Chapter 22 Review

Chapter Summary

Chapter Summary

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you should understand the following about incident response.

Understand the foundations of incident response processes

![]() The role of incident management is the control of a coordinated and comprehensive response to an incident.

The role of incident management is the control of a coordinated and comprehensive response to an incident.

![]() Learn the anatomy of an attack, both old versions and newer APT-style attacks.

Learn the anatomy of an attack, both old versions and newer APT-style attacks.

![]() The goals of incident response in an organization are to restore systems to functioning order and prevent future risk.

The goals of incident response in an organization are to restore systems to functioning order and prevent future risk.

Implement the detailed steps of an incident response process

![]() The major steps in the incident response process are preparation, incident identification, initial response, incident isolation, strategy formulation, investigation, recovery, reporting, and follow-up.

The major steps in the incident response process are preparation, incident identification, initial response, incident isolation, strategy formulation, investigation, recovery, reporting, and follow-up.

![]() Develop a detailed understanding of the components of each of the steps.

Develop a detailed understanding of the components of each of the steps.

![]() Understand the linkages and interconnections between key process steps.

Understand the linkages and interconnections between key process steps.

Describe standards and best practices that are involved in incident response

![]() Modern systems should expect to exist in a state of compromise and have policies and processes designed to operate under these conditions.