Chapter 7

Why Brand Matters

One of the building blocks of any brand is trust. A brand is what ultimately expresses the personality of a company. For financial services companies, because the product itself and its delivery are intangible elements, the brand plays an even more important role. Private banks in the past tended to pay little attention to marketing and branding. This has changed today. One reason is that there are more companies in the industry, allowing clients to be increasingly selective. Branding sets a bank apart from its peers and sends a message that the promise of competent and high-quality service excellence will be met. Our industry also has grown increasingly global in its approach. A strong brand is one of the things that unites a company operating in many different regions of the world. It is therefore important to examine the reasons why brands have even come to be used by private banks, which is a recent development, compared with the history of branding.

THE ORIGINS OF BRANDING

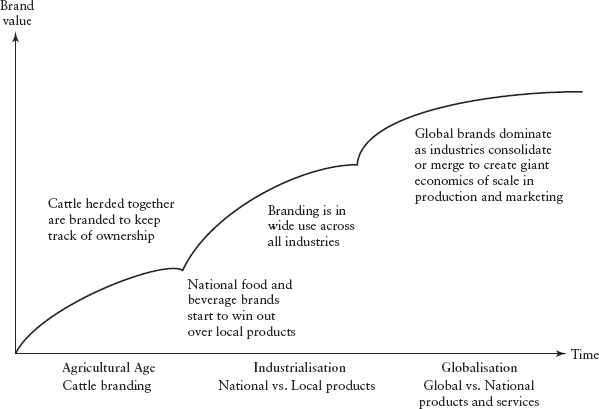

Branding in its earliest form was already practiced in ancient Egypt. Marking the hide of an animal to signify ownership proved to be very practical. Once branded, cattle belonging to different owners could be herded together (a shared investment) and still be easily separated for sale (profit-taking). Where free-range grazing was common, such as in the American West and Australia, branding evolved and owners began to register their brands to prevent duplication. During the industrial age, branding became increasingly common for products. Modern branding really took off in the latter part of the 20th century, as its principles were applied not only to products but to services. Companies realised consumers can emotionally relate to brands (see Figure 7.1, Three Waves of Brand Evolution).

In the meantime, brands have become extremely valuable assets. In 1988, when Philip Morris purchased Kraft for six times what the company was worth on paper, the price was justified partly by the perception that what Philip Morris really was getting for its money was a number of famous brands, including not just Kraft but also others familiar to American households such as Velveeta (a cheese product), Miracle Whip salad dressing, Philadelphia cream cheese, and Parkay margarine.(1) Globalisation has taken local versus national competition to a whole new level.

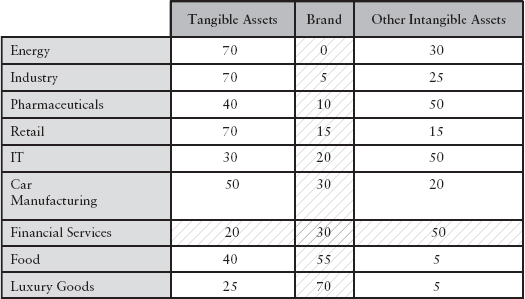

Companies specialising in brand management have developed sophisticated ways to assess the value of a brand. Table 7.1 shows the estimated shareholder value attributable to the brand across various industries. In financial services, altogether 30 percent of shareholder value could be attributed to brand value. This development has been led by pioneers such as Citigroup, HSBC, and UBS, which pursued global expansion strategies that have included a strong brand agenda.

TABLE 7.1 Shareholder Value Attributable to Brand Strategy across Different Industries

Source: Doyle P., Brand Management, Vol 9., No 1, 2001. 20–30 September (from data supplied by Interbrand), reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

As brands have become more important globally, they sometimes have provoked a cultural backlash, becoming the target of heated debate. Modern consumers today are fairly knowledgeable about branding and understand that their choices are influenced by them. But a company can still appeal to their emotions, thus influencing customer choices through branding, providing it is done in a transparent and honest way. In this sense, branding has come to symbolise a relationship or a reputation. It takes years to establish trust, yet this trust can be destroyed in a single instant. A major misstep or crisis, even if it affects only competitors, can cause collateral damage. Losses resulting from actions of individuals such as a rogue trader may cause serious harm to the reputation of the whole financial industry. Building a strong brand also takes discipline, as well as a lot of time and massive investments. But done properly, the rewards of branding can be great.

THE FUNCTIONS OF A BRAND

Modern brands are bearers of an image and express qualities such as trust, allowing clients, potential clients, staff, and others to distinguish the characteristics associated with a particular brand from others in the same industry. Brands create the impression that the product or service associated with them has certain qualities or characteristics that make it special or unique. A brand is therefore one of the most valuable elements in communicating what the brand owner can offer in the marketplace.

Brands exist because consumers are faced every day with an overwhelming number of choices. Making the wrong choice entails a risk. Brands represent predictability and reliability. This is one reason why branding in the food and drink industries has proved so successful over the years. If all colas were the same, who would care whether they purchased Coca-Cola or a discount soft drink? Throughout the world, Coca-Cola represents more than the enjoyment promised by the invitation to come to the “Coke Side of Life.” As a recognisable brand, it is a known beverage, offering security in a sea of competing, unfamiliar choices. An analogy can be made to private banks, which began to take brand management seriously during the good years when markets performed well and the main risk lay in missing out on gains. The greatest potential for branding today exists primarily due to heightened concerns about risk. As industrial nations struggle back from recession and face enormous fiscal debt burdens and the threat of inflation, risks cause clients to opt for the security and trustworthiness of known brands that project a personal and sensible approach.

But even in banking, how can one tell the difference between two financial institutions when both offer the same third-party products? At certain levels, products and even financial advice can be considered a commodity. The rules for a balanced portfolio don’t change because one is speaking with a large universal Swiss bank or a large universal US bank, even though there may be some minor differences in execution. If the product is not unique, external packaging and the service delivery become increasingly important, creating new opportunities for brands. In an age when suppliers and producers of parts and products may increasingly be separated from the companies selling to consumers, brands survive despite the fact that those products or services are indeed intrinsically complex and differ in ways too subtle for many clients to efficiently evaluate and compare. In such cases, brands allow companies to differentiate themselves—sophisticated versus simple or exclusive versus accessible. A brand is a way to offer orientation to those facing what otherwise would be an overwhelming sea of choice during times of great uncertainty. The brand allows the origin of a product or an offering to be identified and ordered within a manageable set of categories, including those derived from previous experience.

There is also a social function at work. Brands define cliques and offer individuals opportunities to identify themselves with ownership of or access to a particular image. If there is a marginal difference in quality sufficient to sway the client’s decision in favour of one brand, the brand owner will be able to command a premium. In other words, strong branding also confers greater pricing freedom.

Finally, because a brand’s power is directly linked to previous experiences with that brand, there is no such thing as an instant brand. Building a brand takes time.

In summary, brands exist to simplify choices when:

- An overwhelming number of choices exist.

- The wrong choice entails a risk.

- Differences are latent—they’re evident only long after the purchase is made.

- No real differences can be identified, such as in the case of commodities.

- Differences are so complex they cannot be effectively evaluated by clients, customers, or others outside the company without expending a great deal of time and effort.

WHY IS BRAND SO IMPORTANT IN PRIVATE BANKING?

Increased competition and declining client loyalty are profoundly changing the market and business environment for private banks. Brand building offers a way to counter these trends. Brands allow companies to differentiate themselves from peers and leverage positive associations to build trust and loyalty.

A brand is far more than just a name or logo. It embodies values and standards that constitute the banner under which a company creates and organises products and services to foster and fulfil client expectations. The brand image is a symbol containing all the information and expectations associated with a company. The brand experience is what the brand delivers in terms of interactions, ranging from seeing an advertising billboard to direct encounters with the company. While names and logos have been around for quite some time, professional branding in private banking is a fairly recent development. This chapter explains why branding has become so important. It also discusses why effective brand management can add value for shareholders, clients, and employees, especially in times of crisis.

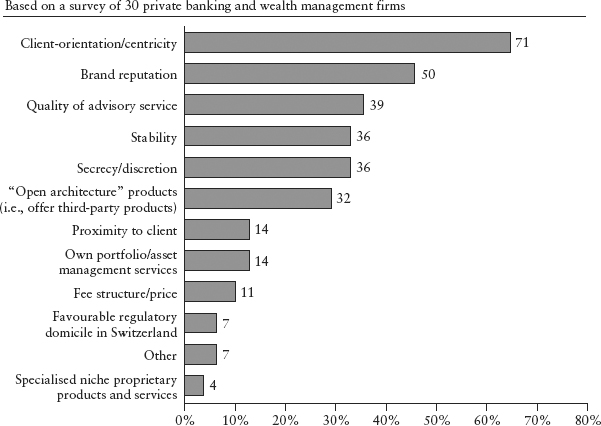

A Swiss study found that brand reputation was the second most important aspect of a private bank’s value offered to the client (see Figure 7.2), after client orientation. Those institutions surveyed indicated that “brand reputation” was of greater importance than elements such as quality of the advisory service and fee structure.(2)

FIGURE 7.2 Most Important Aspects of a Private Bank’s Value Proposition

Source: KPMG, University of St. Gallen. Private Banking in Switzerland—Quo Vadis? 2009

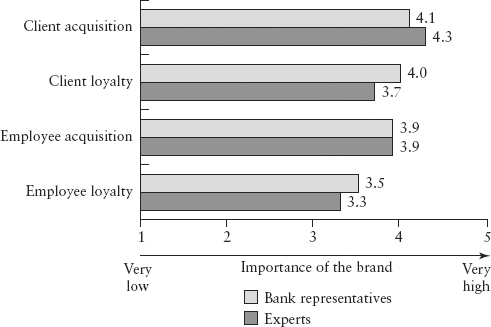

According to research by Gwen Walbert,(3) an expert in bank marketing, it was only recently that most Swiss private banks gave much thought to active brand management. As late as the 1970s, one of Switzerland’s leading private banks, Geneva-based Pictet, lacked even a logo. The sign on its door said simply, “P. & Cie.” But things have changed. By the late 1990s, many Swiss private banks had adopted an active brand marketing strategy. By 2005, around 30 percent of Swiss private banks were found to be making greater efforts to actively treat a complete brand strategy as part of the central focus of their corporate strategy, according to Walbert in a study published in 2006. Based on the findings presented in Figure 7.3, brand experts and bank representatives were consistent in ranking brand as highly significant, in attracting both clients and employees. Awareness of the importance of brand is today firmly entrenched in the private banking industry.

FIGURE 7.3 Importance of Brand in Client and Employee Acquisition and Loyalty (Based on a Sample of 68 Bank Representatives and 11 Experts)

Source: Gwen Walbert. Der Erfolgsfaktor Market im Private Banking aus Sicht des Markeninhabers. Dissertation, 2006

Walbert went on to examine the implementation of brand management principles among Swiss private banks in great detail, arriving at the conclusion that private banks have much room for improvement. So, what is holding the industry back? The following points, according to Walbert, provide some insight:

- The nature of brand management is misunderstood. Senior managers often mistakenly perceive brand building as a creative exercise related mainly to advertising.

- Banking services are often complex and abstract, making it more difficult to effectively implement branding.

- Some Swiss private banks may rely too much on “location branding” (e.g., “Swissness”) without sufficiently differentiating themselves beyond this single feature.

- The Swiss offshore banking culture is characterised by modesty, secrecy, and discretion, making it hard to reconcile with efforts to strongly differentiate a particular brand.

Despite these hurdles, it is useful to highlight some of the most important aspects of brand building; including the origin of brands, why they are needed, what banks can learn from premium brands, and why consistency matters more than creativity. It is important also to look at brands’ personality, or “DNA,” and how brand positioning works in practice, along with what is commonly referred to as “behavioural branding.” This refers to reenforcing the brand’s values among those most closely associated with it—namely the employees. In private banking, the employee very much is the brand. The final part of this chapter is dedicated to examining other channels and activities where a greater awareness of the brand DNA is vital—sponsoring, events, and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

HOW PREMIUM BRANDS THRIVE

Premium brands can be considered high-performance systems that have taken the rules of branding to the extreme, balancing added value inherent to the product with the value and prestige associated with the brand. Private banks and companies associated with premium brands have many things in common. They serve the same client group and are positioned in the high-quality segment of their respective industries. Valuable insights can therefore be gained from how premium brands approach branding.

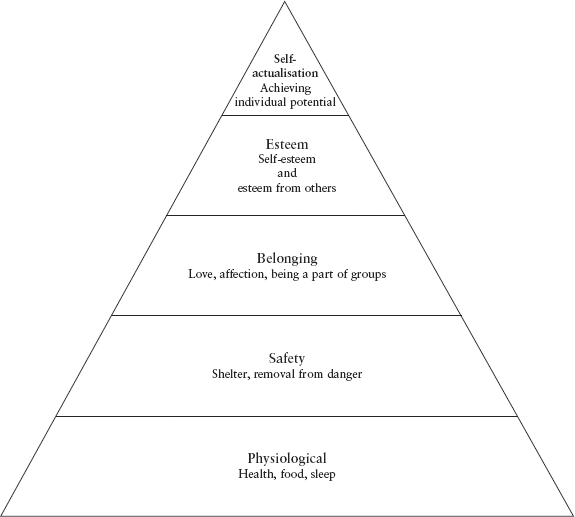

Consider Figure 7.4. Premium brands target a world where bills always are paid and food is always on the table. Similar to private banks, companies associated with premium brands cater to the two top levels of the pyramid based on psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs: self-actualisation and self-esteem. At this level of the pyramid, premium brands target human needs that go beyond the basics. No one really needs to own a handbag costing as much as an automobile, or an automobile that sells for the price of a single-family dwelling. On the upper levels of the pyramid, however, some clients seek meaning and fulfilment in symbols of prestige and accomplishment, including through ownership of famous-brand products. In private banking, clients at stratospheric wealth levels want portfolio growth not because they need the money but because they would like to have the sense of having accomplished something in their lives, allowing them to leave a legacy—for example, a hospital, a museum, a research facility to develop new medicines, or a charitable foundation.

Looking, for example, at the luxury goods industry, a number of key characteristics and mechanisms can be identified that are used to define the brand:

- Highest level of quality

- Pride of origin and tradition

- Consistent positioning

- Exclusivity

- Carefully managed evolution

Premium brands operate globally but strive to keep the connection with their origins. IWC is not just a watch—it is a Swiss watch. Versace is an Italian fashion house. Hermès is a maker of top quality leather goods and other luxury items based in Paris. These brands carefully cultivate the image of a location rich in tradition and heritage.

Premium brands maximise quality and communicate this benefit. Only the best raw materials are used. Processes are carefully optimised. Top designers and craftsmen work hand in hand to create products that excel in all respects.

Consistent positioning means to be true to the brand’s identity and operate in accordance with the natural rhythms of the business and product life cycles. Premium brands are unperturbed by short-term events and never confuse their clientele with unexpected repositioning, as sometimes happens in retail and consumer markets. A true premium brand would seldom, if ever, compromise its brand by lowering its prices significantly to attract sales.

Exclusivity also plays a part. Much of the appeal of a premium brand stems from careful “boundary management” or a policy of exclusion. Belonging to the elite of those who can afford a given brand has a powerful pull. The less accessible, the more attractive the brand becomes to the owners and potential owners included in this select group.

Unadulterated innovation and spontaneous creativity rarely bear fruit commercially, because the adoption of innovation requires a paradigm shift of thinking or behaviour that, at least in brand terms, is closely linked with the company the brand represents. Aware of this, premium brands carefully manage their evolution and cultivate their image. Drawing on their own heritage, they introduce changes in increments, in order to subtly exploit new techniques and trends, while remaining fresh and relevant in the process. They introduce creativity in small doses in order not to risk alienating their established clientele.

Although some might argue that banks are in the business of making money and keeping it safe for clients rather than selling luxury watches or shoes, it is a fact that premium brands and private banks tend to target the same clientele. The affinity between such brands and private banks also is evident in the common efforts to target resorts and towns frequently visited by wealthy individuals such as, for example, in Switzerland—St. Moritz, Verbier, Crans-Montana, and Ascona.

BRAND BUILDING REQUIRES DISCIPLINE AND CONSISTENCY

Branding is not rocket science. Neither is it strictly about creativity. Branding is about discipline and consistency. It requires major investments over many years.

When one considers the star designers and creators of premium brands, one understandably might associate brand management only with creativity. But this would be incorrect. Branding is about discipline. Professionally creative people understand this, while amateurs often confuse improvisation with creativity. Branding may involve being creative, but it takes place within a very strict framework. Adherence to self-imposed rules maximises the effect. For example, Julius Baer launched a brand campaign based on the theme “Unknown Masters.”* Its focus went beyond conventionally famous people, to discover those behind the scenes whose extraordinary craft, skill, and discipline have enabled others to excel and achieve fame. While the person featured as a “Master” changes from advertisement to advertisement, the tone and presentation is always the same and the photography consistent. There is no instantaneous satisfaction here. But the campaign appeals to a sophisticated audience, with subtlety and substance, by consistently implementing and reinforcing brand values.

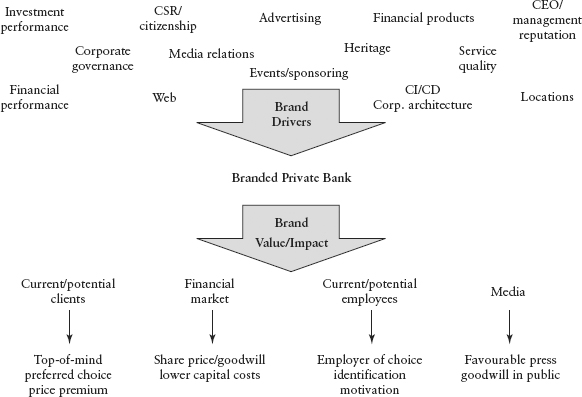

Branding is also much more than advertising; it is a sum of the various parts, meaning that all aspects of the business process and company performance contribute to the brand’s impact, as shown in Figure 7.5. The brand value is derived from the ability of a brand to sway clients in favour of the company, create goodwill among investors, motivate employees, and generate favourable press.

BRANDS HAVE PERSONALITIES AND “DNA”

To manage a brand, it is imperative to first understand its heart and soul. These qualities are the core concepts that drive the creation of products and services and the relationship with clients. The evolution of the brand and the company behind it is expressed in the concept of the brand’s “DNA.”

If a client can develop a psychological relationship with the brand, can the brand be personified and identified in terms of its character? If the brand were a person, what would he or she be like? What clothes would that person wear? What sort of voice would that person have? What music would that person listen to? These questions reflect the soul of the brand. The heart of the brand has to do with its vision—what one could call raison d’être or mission. A company exists to create value for the shareholders, but the company’s brand needs a purpose or a goal beyond this. To simply increase market share does not go far enough. If a brand can answer the question of what the market would lack if that brand did not exist, it is well on the way to knowing its purpose. Strong brands are more than market players—they define the market in some way. The name Ford alone for many once defined the essence of the automobile. Today, simply recalling Google, Microsoft, or Apple sums up many people’s daily interactions with technology, just as McDonald’s is synonymous with fast food and franchises. All of these companies were founded and led by charismatic visionaries who gave their companies a specific sense of purpose. A brand needs to embody the purpose that once inspired the founder, allowing it to evolve so that it can develop new products, services and markets.

Examining the history of a brand, it is possible to identify its DNA; this reflects the collective perception of the brand based on the earliest first impressions, memories, and expectations associated with it. These might include a successful product that defines all others in the same line—for example, Tupperware® became synonymous with parties to sell these products. In many cases, the perception of the brand is strongly linked to these early associations.

Besides the seminal milestones in creating the brand’s “DNA,” there are the current associations that relate to the most recent experiences where one might have encountered the brand. These include client experience, taking in a range of advertising and public relations, aspects of corporate social responsibility (CSR), performance, and overall satisfaction with the brand. In addition to seeking to evolve, a brand needs to stay true to the features that first attracted customers. The DNA, the heart and soul of a brand, define the brand’s potential future path. Going beyond the boundaries set by the DNA of the brand will weaken its image and confuse clients. This may happen if a company introduces products or services that radically deviate from its core identity. In 1950, the company founded by Marcel Bich and his partner Edouard Buffard introduced the BIC® ballpoint pen, an undisputed revolution and unique success story. But when the company ventured into perfumes in 1988, these flopped. The company has stopped selling perfumes except in a very few markets.(4)

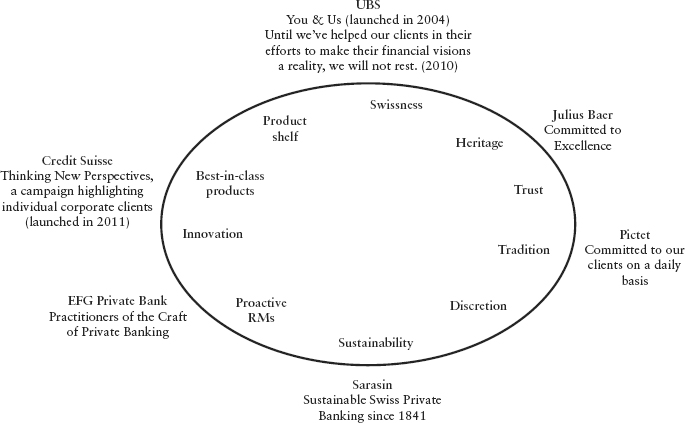

Brand positioning means carving out a niche—establishing the name, logo, values, and standards that differentiate the company from its competitors. A private bank brand must be a premium brand. This means that brand communication, from creation to advertising, will necessarily be done at the highest level. A brand should help to differentiate a bank from its competitors, perhaps with values such as those illustrated in Figure 7.6. But how does this work in practice, and what resources does it entail? As with all premium brands, creative professionals must be employed who are capable of developing ways to set the company’s offerings apart from those of its peers and managing the related advertising campaigns. But branding, as previously noted, is not about creativity in the conventional sense. It is about being consistent and true to one’s identity. For example, one needs a photographer capable of rendering the brand in incredible images that express its “soul” and able to do this not just once but over and over again.

One example of using the brand’s DNA to advantage is the “Unknown Masters” campaign used by Bank Julius Baer. Starting with the bank’s brand values “passion, care, and excellence,” “excellence” was rapidly singled out as having the most potential impact, even though it also was the most challenging to express. By adopting the “Unknown Masters” approach, the bank was able to convey excellence implicitly rather than explicitly while subtly upholding the importance of discretion. The “Masters,” the experts featured in the campaign, are perhaps known to connoisseurs but operate out of the limelight in tireless fashion to achieve excellence in their respective area of expertise. For example, by highlighting the voice coach of a famous opera star, or the acoustic engineer for cars produced by a well-known automotive company, emphasis is on the results achieved by that person’s efforts, rather than the person themselves. In these advertisements, the Masters explain their understanding of excellence in their field in a manner that underscores the bank’s own values. On the corporate website, the bank quotes these individuals at length, allowing them to tell their stories in their own words and explain how they achieve excellence. This reflects the sophistication of the bank’s advisory process. In other words, the message is, “you can’t reduce good advice to sound bites.” Finally, the visuals express the brand’s identification with both simplicity and luxury.(5)

PRACTICAL CHALLENGES OF GLOBAL BRAND BUILDING

For global brands, everything has to work flawlessly and seamlessly across cultures and continents. The solution is the oft-cited but difficult-to-put-into-practice adage to “think global, act local,” creating a brand with universal appeal and ensuring that it is suitably adapted to each regional market.

Alain Zimmermann* recalls the experience of rolling out the Julius Baer brand in Asia:

When we began planning a Julius Baer presence in Asia, we faced a lot of questions, starting with the name. How will the Chinese cope with the pronunciation? After a lot of debate we decided, based on the brand DNA and the bank’s traditions, that we would definitely keep the name. Working with experts, we developed a Julius Baer descriptor in Chinese characters to accompany the logo. This process included obtaining clearance from a Feng Shui master.

The importance of checking the local cultural implications of everything relating to the brand must not be underestimated. Well-known to those in Asia, for example, the number 4 commonly is associated with bad luck, whereas 8 connotes luck or good fortune. Therefore, a brand must avoid an address or telephone number containing a 4. Aside from names and numbers, every image used and every written formulation needs to reflect the core brand values and DNA applied to the culture that is being targeted.

The brand also requires equally professional implementation in terms of establishing it in the public eye, using excellent media planning and advertising to ensure that the company gets the full impact and derives all the benefits. When building a brand, the common approach is to apply the media strategy to entire markets or regions. But the fact that advertising used by financial services companies is strictly regulated in many countries makes this a difficult proposition for a private bank. International publications such as The Economist or the Financial Times reach many markets, but the price tag for advertising in them is correspondingly high. To be able to build a brand properly, a bank must be either a large global player or a boutique focused on a single market. It is very difficult for those positioned between two opposite ends of the spectrum to succeed in this area.

What about television? In certain markets such as Europe, television advertising is often considered unsuitable for private banking and some premium brands, because it is perceived as a retail medium. In Asia, by contrast, some experts believe that television advertising is a must: it conveys financial muscle, success, and trustworthiness. These are essential attributes necessary to attract clients and potential employees. This name recognition is thought to be important in cultures where it matters that one’s immediate circle of friends and relatives have heard of and are impressed by the name of a bank or potential employer. Hence, brand building here is critical. But private banks’ approach to television focuses on large international broadcasters such as CNN, CNBC, or Bloomberg Television, as opposed to national TV networks.

IMPORTANCE OF BEHAVIOURAL BRANDING

Brand management in private banking has both an external and an internal dimension. In businesses that rely on service, including private banking, it may rightly be said that the bank’s employees are the brand. They embody the values and deliver the service in a manner that either satisfies and builds trust in and satisfaction with the brand or in the worst case, destroys brand value.

The essence of what may be described as private banking’s value proposition is the way it manages assets of an individual or defined group or those of a wealthy family. This is done by a trusted and discreet relationship manager (RM). The bond between an RM and his or her clients can be so strong that clients sometimes are more loyal to the RM than to the bank. Clients may prefer to move with the RM if she or he changes employers in order not to break this bond. Having said that, clients today also have grown accustomed to having multiple private banking relationships and their investments have become more intertwined with the systems and products of the bank. This has weakened the bond to the RM and has created an opportunity for the brand to help to secure clients’ loyalty. Clients who really believe in the brand are more resistant to the temptations of a rival brand. So, one might add, are the employees.

This factor makes it even more worthwhile to invest in and strengthen employees’ perception of the brand. The Ritz-Carlton®, for example, immerses new employees in the brand values and requires all of them to complete an annual training certification for their position. Apart from the training related to the position, the group drills employees in its service credo: “We are ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.”(7)

Internal branding is also vital because a positive experience is generally attributed to the individual employee whereas a negative experience is attributed to the brand. A brand-conscious employee is less likely to behave in a manner that is contrary to corporate values and is more likely to give the brand credit where credit is due.

Internal branding can be achieved by applying the principles of brand management to the available internal communications channels. These include employee magazines, virtual communications, and training via the Intranet along with offering real activities ranging from workshops and seminars to staff leisure opportunities.

ALTERNATIVE BRAND CHANNELS

Today, it isn’t only advertising and employee behaviour that project brand image and experience; a company also must manage everything from interior design to its online reputation, public relations, sponsorship, and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Each of these areas poses a unique challenge. To benefit the brand, sponsorship needs to be very carefully and explicitly aligned with the brand’s DNA. To be authentic, CSR has to be clearly separated from the branding process and any marketing considerations.

The Internet as a Challenge to Controlled Branding

One cannot discuss modern branding without mentioning the impact of online social networks, blogging and other interactive networks. The corporate Goliaths that once controlled their image through access to television and the print media have found that consumers can today in no time respond with email campaigns and YouTube or Facebook postings, and within a matter of hours or minutes, these comments can snowball and resonate around the world.

Corporate Social Responsibility

No one admires a phony brand. This means that corporate social responsibility initiatives have to be inspired by genuine concern about an issue, as opposed to simply being an extension of brand marketing. Of course, CSR activity, whether it be environmental auditing or charity donations, should be true to the brand. If one of the brand values is tradition, then the company must demonstrate a long-term commitment to CSR. For a private bank, one prized quality is discretion, so charitable activities should remain discreet. But discretion should not be confused with secrecy. One can do good and talk about it. But the key challenge is to be motivated by a genuine desire to achieve something positive.

Sponsoring

Today sponsorship is a widely recognised element of brand management, used also in retail banking, and includes major events such as popular football (soccer) matches and tournaments. Sports lose none of their universal appeal as one’s net worth increases. A private bank could easily cater to the elite tastes of their target group by providing VIP facilities and functions tied to major sporting events. But a private bank needs to look for a natural marriage with its brand’s DNA. Is the sport associated with privilege, exclusiveness, confidence, trust, tradition, and discretion? The arts also offer an attractive opportunity for private banking sponsorship, as they represent the upper level of the Maslow pyramid (see Figure 7.4). However, a bank seeking to position itself by sponsoring the arts faces a number of dilemmas. There is significant competition from a great many sponsors. Tastes also vary more strongly in arts than in sports; one can attend a game and interact socially even if one is not passionate about the sport. But if you don’t like the music, you cannot start a conversation during a concert. Television coverage of sports events provides more visibility for the logo to be seen than is possible in coverage of most art events. But while a sports stadium is a suitable venue for banners advertising sponsors’ brands, such a display would be entirely out of place in an opera house.

CONCLUSION

Brands can make difficult choices look easier when clients are confronted by oversupply or face heightened risk and when differences are not always obvious (when products are commodities), or are so complex that it is hard to decide which is the most suitable. Brands also can serve to distinguish between service providers, conferring prestige upon clientele who identify themselves with these brands. Premium brands allow their owners more freedom with regard to pricing, while limiting any radical attempts to change an image or service and product line overnight. Private banks are long-term entities, accustomed to thinking in terms of decades and generations rather than single-year product cycles. Despite these banks’ traditional values of modesty and discretion, branding has emerged as a vital tool, allowing them to differentiate their offerings in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

Private banking can draw inspiration from classic premium brands. Building on heritage and proud of their origin, premium brands appeal to the privileged few by providing the ultimate in product quality and superior service. Premium brands’ careful approach to any changes in terms of their positioning can be applied equally well to private banking. Radical surprises should be avoided. Trust is optimised when change occurs as a gradual evolution.

Building brand image is a long-term activity that requires more consistency than creativity. Creativity in brand management essentially means the ability to find fresh and striking variations on familiar themes to continually express the values traditionally associated with a particular brand. By doing so, expectations are generated among clients that must be reinforced by the brand experience, including how the employees conduct themselves along with all the other points of contact between the client and the company. As discussed in Chapter 8, “Client Experience,” if the brand experience is positive and resonates with the expectations generated by the brand image, the brand will not fail to satisfy, and a loyal following will result.

NOTES

1. Sing, B. 1988 Oct 31. Los Angeles Times. “Kraft to Be Sold to Philip Morris for $13.1 Billion.”

2. KPMG, University of St. Gallen. 2009. “Private Banking in Switzerland—Quo vadis?”

3. Walbert G. 2006. Der Erfolgsfaktor Marke im Private Banking aus Sicht des Markeninhabers: Eine auf theoretischen Grundlagen basierende sowie empirische Analyse des Private Banking-Geschäfts der in der Schweiz ansässigen Bankinstitute [dissertation]. Zurich: University of Zurich.

4. Turpin, Dominique. 2005. IMD. “How Far Can You Stretch Your Brands? Perspective for Managers, No. 124, October.

5. Discussion with Alain Zimmermann: April 6th 2009.

6. UBS corporate website. Accessed 20 May 2012. http://www.ubs.com/global/en/about_ubs/brand/ads.html

7. Application Summary 1999. The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, LLC. 2000.

8. Sarasin Sustainability Report 2009. Our Future.

9. The Julius Baer Foundation.

10. Fonseca, D. “Polo is a great sport. This is a great tournament,” Sport 360, 19 Feb 2011. Accessed 20 May 2012. http://www.sport360.com/node/438921

*Bank Julius Baer introduced the “Unknown Masters” campaign in 2007 and continued it until 2011.

*Alain Zimmermann originally came from the luxury industry, where he was active in marketing for many years for watchmakers such as Cartier and IWC within the Richemont Group. He joined Julius Baer in 2006 and left in 2009 to become head of a well-known watchmaker in Switzerland.