Chapter 8

Delivering a Superior Client Experience

Of all the factors that influence client experience, human interaction plays the biggest role. This dimension, the interface with and between the people who represent the institution, is critical. This is also one of the most difficult parts to manage. It is nearly impossible to replicate certain experiences, time and time again, providing the same quality and consistency. In addition, each client is different, and so is each situation. It is imperative for a bank to adapt very quickly to changing situations. While this could seem to be quite difficult to manage, a structured approach and a toolbox to define, implement, measure, and eventually improve client experience is presented in this chapter.

THE EVOLUTION OF CLIENT EXPERIENCE

Client experience means delivering on the qualities promised by the brand. It has become a catchphrase common to nearly all industries. It embodies a number of intangibles, making it hard to define, let alone replicate. Given the nature of subjective expectations and perceived qualities associated with it, can client experience truly play a role in private banking? The fact is, clients today expect much more than just a reliable and trustworthy partner. A brand that is not only associated with good and dependable service, but that also appeals to the senses and emotions is more likely to succeed, no matter what the business. Private banking is no exception, and private banks can hence ill afford to ignore changes affecting how people have come to view companies and the services they provide.

Ask just about anyone how to define what client experience is, and you will likely get a fairly standard response, probably describing something about a particular company, the performance of its products, and the manner in which these are delivered. For a bank, the answer might encompass a range of various subjects and impressions—for example, how friendly a particular relationship manager (RM) is or the quality of the coffee served. Both tangible and intangible elements and comments about people, products, and processes are likely to be included.

The concept of “customer experience” was first widely introduced in an article in the Harvard Business Review. Published in 1998, “Welcome to the Experience Economy,”(1) by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore describes the transformation that has taken place in the customer culture. No longer is it enough for an enterprise to simply excel at its core business. Companies also need to enhance the quality of interactions with existing and potential customers, engaging them on different levels through experiences providing a value as real as that of any service, good, or commodity. In 2007, Christopher Meyer and Andre Schwager went a step further, identifying client experience as “the internal and subjective response customers have to any direct or indirect contact with a company.”(2) They also reasoned that simply measuring customer satisfaction doesn’t say how to achieve it. Customer experience is based on personal and subjective impressions that may not even be directly associated with the company’s actual offerings, making it very hard to measure. This could be daunting to a person more comfortable with facts and figures. But as a great number of products and services increasingly appear interchangeable, we can no longer afford to neglect the reality of this realm.

Clients also are starting to demand more for less, as products become increasingly commoditised and the Internet gives everyone access to nearly limitless information and opinions, including those about businesses and services. Customer experience is one of the most important factors determining whether or not a company succeeds. This holds true for all industries. “When a customer has a good experience with a company, and decides on the basis of that experience to give more future business to it, the firm has gained value at that very instant, with the customer’s change of mind,” according to Don Peppers and Martha Rogers.(3) For them, client experience has become the key factor separating the winners from losers. But obtaining the elements necessary to obtain positive results is never going to be easy. “Building great consumer experiences is a complex enterprise, involving strategy, integration of technology, orchestrating business models, brand management and CEO commitment. It’s harder than you think,” stated US consultant and author Jeneanne Rae, who specialises in innovation and design strategy.(4)

The fundamental developments and trends remain the same whether we speak of products or services, customers or clients.* A company aiming to acquire market share and build brand loyalty must look beyond its customary products and services to manage the totality of encounters. For private banking, the question becomes how to achieve a high level of positive client experience in the area of managing clients’ wealth. How can a business focused on the individual make client experience scalable without losing sight of the fact that every client must be treated as unique?

INSPIRATION FROM THE LUXURY HOTEL INDUSTRY

Again, looking outside one’s own industry can reveal interesting insights. Anthony Lassman, founder and owner of Nota Bene, managers of bespoke travel and lifestyle for an affluent and highly discerning private membership, says upscale clients using these services can develop long-term brand fidelity: “High-net-worth individuals live in a different world. They can be very demanding and impatient, but if you deliver, they tend to be very loyal.”(5)

Many of the major trends affecting industries and businesses, including private banking, are forcing companies to focus on client experience to differentiate themselves from competitors. However, as Lassman puts it, “when we look at the trend towards customised products, we need to remember that high-net-worth individuals always have been able to buy customisation in the form of private tailors, personal fashion designers, specially commissioned works or special editions.” At private banks, relationship managers also try to go the extra mile and organise various bespoke solutions for their clients. The difference now is that clients have come to expect personal and superior treatment not just from the individuals that they personally hire but increasingly from employees of corporations.

These trends are occurring at the same time that global standardisation is becoming the norm, a development that has deprived globetrotting of much of its former magic, says Lassman. “In the past, flying to Asia took me to a different world. Now I am surrounded by familiar brands, especially in the luxury hotel sector. Once, every hotel had a unique flavour. Now that is very hard to come by. The industry today is dominated by huge chains focused on guaranteeing that the business traveller is offered a consistently high standard of service, providing a predictable environment for work and play.”

He adds that the system succeeds due to strictly enforced standardisation. This poses a problem for corporations—namely, how to achieve standardisation while empowering individual employees to provide truly personalised service. “Everything from design and décor to vendor service level contracts are defined and regulated down to the last detail. But all this will be meaningless if the staff don’t get it right,” says Lassman. For example, when arriving at a hotel, it makes a difference whether guests are offered a beverage and a comfortable seat immediately upon arrival or only after they’ve presented their credit card and passport. Or, if a guest needs directions, does the concierge take the initiative and perhaps organise a courtesy car? “A hotel needs regularly to go the extra mile in order to delight the guest,” says Lassman.

The existence of luxury hotel chains proves that it is possible for global companies to organise a workforce that is capable of consistently delivering superior experience on an individual, personal level. And yet we’ve arrived at another dilemma: achieving what is possible soon becomes merely the client’s “expected standard.”

In the following pages, we shall look at how client experience originated; the technological, social, and political trends behind its evolution; and its growing importance in nearly all industries. In private banking, it has created a new context in which wealth managers compete; for those who understand it, it can offer a number of opportunities.

THE MEGA-TRENDS DRIVING CLIENT EXPERIENCE

Organisations don’t change without pressure. This often comes from external factors, including global competition, commoditisation of services, the need to reduce costs, compliance and regulations, and new technology. It is not just about achieving growth. It is in many respects a battle being waged to retain margin and market share. Facing these imperatives, every company needs to formulate an objective client experience strategy.

Powerful external factors are forcing companies to increasingly value the importance of initiatives designed to enhance client experience. That was one conclusion of the IBM Customer Experience Study 2005, conducted worldwide by IBM with OgilvyOne.(6) Based on interviews with consumers, companies, and experts, one key finding was that there is an oversupply of most products and services. People can choose amongst multiple offerings from scores of rival providers. Just getting attention in such an environment has become a challenge. Competition now takes place on a global scale. Organisations face more rivals than ever, some operating with lower costs. Increased travel, international media coverage, customer confidence, and the ability to purchase goods and services online mean consumers no longer need to stick to familiar brands. Nontraditional rivals also are new on the scene. Companies can be challenged by mega-brands spanning many industries. For example, today travel agents and tour operators no longer compete just with each other but with a whole range of other booking services offered by nontraditional providers, even supermarkets—not to mention a range of services that has sprung up via the Internet, which allows simple price comparisons and bookings. Online services have radically changed many industries. Even in wealth management, there is a similar move afoot among some providers to use the Internet in a more targeted way. In one instance, a well-known Swiss private bank, through a fully owned subsidiary, allows clients to manage their assets online, offering standardised investment solutions catering to those with smaller amounts to invest. The new bank started in 2010 and aims to have as many as 5,000 customers with total assets of 750 million francs within three or four years after launch.(7)

Products also are subject to increasing commoditisation and cost pressures; the gaps between different products are closing faster than ever, and a continuous drive to reduce prices and costs makes it increasingly difficult to stand out from the crowd. Consumer sentiment may be less easily swayed by new features. Customers may also perceive little difference (other than price) between competing products or services. In financial services, it may happen that some products and services appear almost identical. If clients start to feel that the performance of more innovative offerings is mainly a function of the market as opposed to a single institution’s efforts to enhance its services, the competitive advantage is lost. Compliance also raises many issues: the more demanding the regulatory environment, the narrower the range of business and product models permitted.

Meanwhile, new distribution channels and technology throughout all industries offer clients a range of conflicting choices, together with a confusing array of alternatives. Even when the underlying products are identical, technology allows marketing executives to discover new ways to bundle pricing and products, making it harder to measure like against like. Try comparing two competing mobile phone operators’ pricing schemes, for example. Or, for that matter, try to compare the latest structured financial products offered by two different banks.

Finally, relentless cost pressures are forcing companies in nearly all sectors to lower the prices of their services. This is often achieved by increased use of automation or by outsourcing some services. If the benefit far outweighs what might be lost through immediacy and the personalised human touch, then such innovations will be welcomed. For example, people would never give up 24-hour access to cash provided by automated teller machines (ATMs). But reaching a voicemail or recorded message is almost universally perceived as annoying. No one expects a bank to be open around the clock, so the ATM constitutes a delightful advance. But delight in progress and technical innovation turns to dismay at the sound of a recorded message; most people prefer to reach a human being on the telephone, not an automated recording.

The upshot is that companies are being forced to rely more on client experience to differentiate their offerings and to attract and retain customers. In fact, companies rank client experience high among factors crucial to revenue growth, placing it ahead of controlling costs through operational efficiency, based on the IBM/Ogilvy study on customer experience.

But how did the idea of client experience originate? How does it work? What social, political, and technological developments paved the way for its introduction?

UNDERSTANDING CLIENT EXPERIENCE

The evolution of client experience might seem an intuitive process. After all, everyone buys things and most people have an impression of the provider. But for a long period, there was no standard way of evaluating what made the experience positive, nor any systematic way to keep track of what worked. As modern technology provides consumers with an ever-increasing array of choices and new markets open up to global brands, it is imperative to understand how expectations and perceptions change.

The Impact of Technology

The concept of client experience within corporations developed through a series of technological advances that allowed companies to better understand clients, communicate more personally, and ultimately offer customised products to the masses.

Customer relationship management (CRM) is considered to be the forerunner of client experience. In the 1980s, thanks to advances in computer processing power, an increasing number of businesses were able to gather and use information about customers and their spending habits. Companies tried to harness the data to take advantage of cross-selling opportunities. Customers were segmented and then received targeted offers through advertising campaigns relying on direct mailing. Over time, complex loyalty programmes arose. These typical marketing activities are still widely practiced today. Frequent flyer clubs are one of the earliest attempts to combine insight about a client’s spending patterns with financial incentives and an experience component, which was represented by the frequent flyer lounge, seat upgrades, and other mileage rewards.

The arrival of the Internet provided a major boost to this approach. Companies were suddenly in position to track not just a client’s spending habits but his or her personal interests. This growing market, supported by more powerful computers and new integration techniques, allowed software designers to dig deep into the data to study patterns and preferences in real time and come up with some astonishingly powerful and personal marketing tools. Google AdWords and Amazon’s book suggestions are two common examples of how CRM has come of age and is setting new standards. Clients now expect companies to be able to respond very specifically to their current needs and interests rather than simply providing a modest incentive based on what they bought in the past. At the same time, the ease of storing and using information has raised worries about the intrusiveness of data mining. Clients have grown fearful that their privacy is being invaded, and the threat of data security being compromised is common in both public and private life. Businesses therefore have the duty to balance knowledge about clients with the imperative of safeguarding their information.

Powerful production management and logistics software also paves the way for companies to begin offering so-called build-to-order (BTO) products. In 1976, when buying a new car, it was necessary to go to the local dealer and choose from among what might have been five models on offer, in perhaps three colours and with two options. Today, it is possible to go online and research 20 brands. Once a buyer decides on a particular model, he or she can configure it to exact specifications. The car manufacturer will not begin to build the car until receiving the order. This is possible only because of technology that enables advanced supply chain management and just-in-time logistics. These techniques have developed under relentless cost pressure and the need to minimise risks and capital tied up in inventory. Aiming for more customisation also is a trend in banking, where it is now possible to offer highly personalised services, such as individually tailored structured products, to investors.

To summarise, processing power allowed the evolution of CRM. The Internet has put power in the hands of individuals, flattening the market by offering increased access to information and, in the end, accelerating the pace in nearly all aspects of business.

The Impact of Social and Political Changes

Economic developments in recent years, especially in countries such as China and India, have helped to unlock enormous potential in many areas. Luxury brands and services targeting the masses proclaim what seems almost to be a new basic human right—to be a pampered and highly fashionable client. Economies hardly thought of as dynamic only a couple of decades ago today are leaders in economic growth. Globalisation has contributed to the rise of a new affluent class. For people in many countries, the standard of living continues to improve. With the growth in wealth in what today are still termed “emerging” economies has come the need for universally recognised symbols of success.

The changes resulting from globalisation also have affected Switzerland. Twenty years ago, the majority of the shops on Zurich’s prestigious Bahnhofstrasse were uniquely local businesses. Only a few stores offered a single global brand. Today, the situation is the opposite. The majority of the shops and boutiques are purveyors of global brands, while local businesses constitute the minority. A stroll through Zurich takes you past exclusive hotels, restaurants, cafes, and shops, all featuring stylish interiors, staffed by polite employees speaking several languages. To survive in such a cosmopolitan centre, businesses have been forced to focus on delivering a superior client experience. Clients’ mentalities are also changing. There was a time when luxurious goods and services were available only to a privileged minority of wealthy individuals. Shops or service providers tended to dictate the terms. The vast majority of consumers had relatively little choice. The old adage “the customer is always right” or some variation thereof (e.g., der Kunde ist König) had yet to be accepted as a universal business philosophy. Whether or not customers were satisfied, as long as they had no alternatives and mobility was limited, they remained customers. Where else could they go?

That, of course, has changed. Globalisation and the advent of a customer service culture have affected private banking and are continuing to have an impact in terms of competition and service. In the past, political instability in many countries made them unattractive places to deposit wealth. Life back then was easier for Swiss private bankers. Clients seeking traditional values associated with a Swiss account, including safety and privacy, were not much concerned by what today would be considered the client experience factor. No one expected banks to offer clients a luxurious welcoming lobby. In fact, Swiss banks even today avoid expenditures that would be considered extravagant, indiscreet, immodest, or wasteful.

Yet things have changed, and banks have made concessions to client comfort. One reason is the growing competition, including the number of centres springing up around the world where clients can go for wealth management services. Clients are much freer to choose where and with whom they bank. The greater choice increases competition, as clients can just as easily bank in Singapore as in Zurich. The range of services required today is in many ways much different from in the past, often taking place in real time while maintaining standards common to the luxury industries.

PHASES OF CLIENT EXPERIENCE

Client experience can be analysed in three phases; one needs to understand each of these separately, while recalling that in the client’s mind, these individual processes may actually overlap.

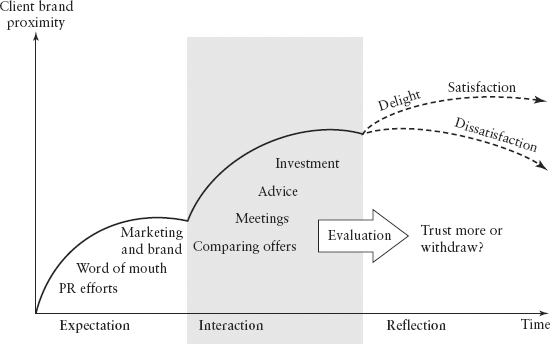

Expectation, interaction, and reflection make up the three distinct stages of client experience, as shown in Figure 8.1. During the first phase, expectation is created, as detailed in Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters.” This is done through marketing and public relations. Initially, a great deal of information will get lost as general noise, but repeating the message and providing information from sources considered authoritative will eventually register to form impressions. That is why word-of-mouth marketing also is such a powerful medium and is included in the expectations phase. The recommendation of a trusted friend or advisor is many times more effective than a media campaign.

The prospect may decide to respond to try the brand offering and become a client of a bank, entering the interaction phase. As the client subconsciously compares his or her own expectations with the bank’s actual delivery of products or services, emotions of delight, satisfaction, or perhaps even dissatisfaction may arise. With time, as expectations are heightened, delight might subside and there is a risk that the client, whose expectations continue to grow, will no longer be satisfied. The client’s response can occur on two levels: functional or emotional. Did the product work as expected? Did the investment yield the promised return? Was the account statement correct? On the emotional level, the client assesses all the intangible elements of the interaction with the bank, from the impression of the reception in the foyer to meeting the relationship manager. How genuine were the smiles? Did the relationship manager find the right tone when posing questions regarding due diligence or investment needs?

After the interaction phase, the client taps into perceptions and memory and reflects on the experience. This reflection phase brings the subconscious evaluations to the fore, and the results of the interactions then form a basis for whatever future actions and encounters will take place.

CREATING “DELIGHTFUL” EXPERIENCES

A delightful experience is more than just a heightened version of a satisfactory one. Satisfying clients is the very least a business can aim to achieve. Without it, you don’t have a business. But without going a step further to delight clients, you don’t have a brand!

We all go through life with a set of expectations, which may be fulfilled, leading to satisfaction. If they are denied, they cause disappointment. Happy people are good at formulating realistic expectations and responding proactively to disappointments. Those who are frustrated tend to have difficulty in setting realistic expectations and are not proactive or solution focused in dealing with setbacks or upsets. But both satisfied and irritated customers have one thing in common: they talk about their experiences. Delighted customers are far more likely to talk about their experiences, more likely to come back with further business, and are less price sensitive.(8)

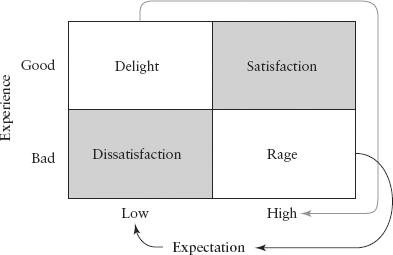

In recent years, experts have highlighted what commonly are referred to as the concepts of customer “delight” and “outrage.”(9) Consider Figure 8.2. It illustrates the relationship between expectations prior to an experience, the experience itself, and the resulting emotional outcomes: delight or satisfaction, rage or dissatisfaction. A low expectation followed by a good experience is considered delightful, whereas having high expectations that meet with a bad experience is enraging. The key to delight is having few expectations. Herein lies the problem for management: you can delight or surprise a client with a gesture only once. As soon as a client or customer experiences delight from the proffered airline upgrade or a free product offered in retailing, he or she will become accustomed to it and have heightened expectations for the next encounter. This time around the stakes will be higher, too. If done properly, one can achieve only satisfaction at best. But get it wrong, and there’s a risk of enraging the client. The challenge for every brand manager is thus to discover ways to deliver incremental improvements in order to continuously delight clients.

FIGURE 8.2 How Past Experience Affects Client Expectations

Source: “A Model of Dissatisfaction, Outrage, Satisfaction, and Delight,” in Barry Berman. “How to Delight Your Customers,” in California Management Review vol. 48, no. 1 (Fall 2005), pp. 129–151. ©2005 by the Regents of the University of California. Reprinted by permission of the University of California Press

CREATING A CLIENT EXPERIENCE STRATEGY

While much of the information discussed so far has been general in nature, the focus in this section is mainly on private banking. It is clear that companies must deliver a superior client experience to set themselves apart from the competition. The approach outlined here offers tools and strategies that can be used with the aim of delivering a superior client experience.

Touchpoints

A systematic overview of all client touchpoints is the simplest way for a bank to identify discrepancies between expectations and experience and to enable it to close the gap.

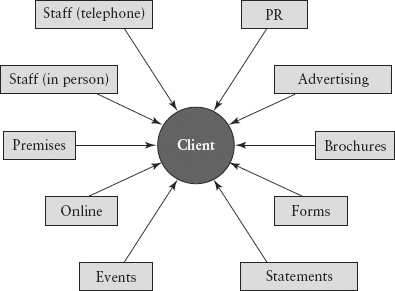

A touchpoint refers to every single encounter that a client has with the bank, whether through interactions with staff; through products, services, or personal communications; or through information and impressions gained from advertising, mass media, and so on. It also includes the client’s experiences with the bank, starting with first impressions upon seeing the building from the street, down to details such as the colour of the carpeting; the manner in which coffee, tea, and other beverages are served; the lighting and condition of the furniture; the artworks displayed; whether meeting rooms are soundproof; and so on. Each of these touchpoints contributes to the overall perception of the brand, which we refer to here as the client experience (see Figure 8.3).

In the following paragraphs, we examine each of these touchpoints and offer a few examples of how they might be improved.

Public Relations

Public relations, meaning interacting with the media and the general public, includes supporting the brand. It explains what the company does and its mission, and showcases key employees, including experts and authorities. Opportunities include speaking publicly at conferences and universities. Select media coverage offers a way to explain the company’s values and philosophy. Publishing opinion leader pieces and insight on expert topics underscores the knowledge available within the company. All these channels may help to highlight the bank’s awareness of key industry themes and its position on various topics and help to raise its profile overall, among clients, industry professionals, and staff.

Advertising

Professional, modern advertising gives rise to expectations that reflect brand values, image, and value proposition. It is all about positioning and finding the right balance between promises, claims, and delivery. This is the tightrope that companies must walk—raising hopes and generating positive expectations to draw clients to the brand but never promising what cannot be delivered. It is better to “over-perform” and “out-deliver,” exceeding expectations to generate positive or “delightful” experiences.

Brochures, Forms, and Statements

All printed materials need to conform to the corporate design (CD) guidelines governing visual and typographical design standards. Corporate wording (CW) is a relatively new addition to this field. It includes a glossary and writing style to ensure consistency in written communications.

To create a superior client experience, it is important to look beyond the basics defined in a typical CD manual. Every single form or printout must be reviewed to ensure clarity and added value—for example, how user friendly is the bank statement? Is the design dictated by the bank’s internal operations, or is it designed to support clients’ need for clarity, convenience, and added-value information?

Events

Sponsoring engagements serve the broader purpose of brand building and informational gatherings directly linked to the bank’s communications objective. Sponsoring engagements is discussed in detail in Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters.” With regard to informational programmes, these can be press conferences or educational gatherings targeting future recruits, prospects, or clients. Events are significant because they allow an element of surprise, which is essential to achieving a truly satisfying client experience. The nature of sporting events or arts-sponsoring opportunities provides ample elements of surprise. Programmes designed to educate and raise clients’ awareness of key topics and themes can be held in unconventional locations. Lights, sound, and staging all may be employed to reinforce brand values, create the desired delightful effect, and communicate information.

Julius Baer hosts investment conferences in Zurich, where by-invitation-only attendees including clients can spend a day with world leaders in a relevant field. One such conference held in January 2011 included top experts in the field of sustainability. Apart from live panels and top speakers, the event was held in one of Zurich’s most prestigious hotels, where those invited could mingle during breaks with the “A-list” panellists, who included professionals known worldwide for their leading opinions and direct involvement in topics such as investing in sustainable energy and eco-efficient vehicles.

Online: Website and e-Banking

The same principles applied to other touchpoints also can be used for the Internet and e-banking, albeit with a separate set of recommendations for online communications. In general, the Internet demands a more concise approach. It requires fewer words to express information than printed texts and is slightly less formal. You don’t need to add “please” and “thank you” with every invitation to “click here.”

An online presence needs to be personalised to create a superior client experience. The website should adapt to regular users’ preferences while respecting the needs of clients from different generations. Although the Internet may be infrequently used by the majority of current wealth management clients, mobile communication is making major inroads into many areas of banking. Such technology is becoming highly important for some client groups, especially younger ones.

Premises

The physical presence of a private bank is a vital touchpoint. To deliver a superior client experience, traditional standards must be improved and should try to exceed the existing standards set by banks. Inspiration can be drawn from cutting-edge architects and designers. Examples include Bruno Moinard, a Frenchman known for his unpretentious yet elegant style, whose clients range from museums to upscale retailers such as Cartier. Even in the details, private banks can offer touches that enhance client experience, an example being fresh flowers, even covering a whole wall, that engage the senses. Not just the sight but the aroma of flowers tells clients that they have entered a very special world.

Staff: Direct Contacts

Employees are one of the most important client touchpoints. From the receptionist to the RM, the driver to the cashier, they all represent the brand and contribute to the client experience. To ensure that employees’ behaviour provides the right client experience and that they represent the brand values, training should be mandatory and ongoing. Training should address the “extra mile” approach that makes a brand more than just a logo. For example, Singapore International Airlines, consistently ranked as the industry’s most admired airline,(10) puts its cabin crew through rigorous training that goes well beyond what is needed to accomplish the job. The airline educates its staff not only in practical matters, such as learning to conquer fear in water landings. It also includes training in wine and gourmet food, as well as in the art of conversation. Employees are given the authority to make any decision up to the competence level of their immediate superior without consultation to allow them to react to unforeseen situations where consultation might result in unnecessary delays.

Banks may recruit graduates from hotel management schools where the focus is on offering a high level of service aimed at putting clients at ease. Some banks may even go so far as to engage colour and style consultants to coach employees on harmonising their style of dress with their physical persona and offer training in social etiquette. The German “bible” for social etiquette, Knigge, even offers a special edition for the banking industry,* and a large Swiss bank made headlines after reports it was testing a 43-page dress code for its staff, a story picked up by international media.**

Staff: Telephone

Apart from direct contact with staff, the telephone probably serves as the most important touchpoint for clients. In fact, clients and prospects have very high expectations regarding telephone service, availability, and responsiveness. What does a superior client experience on the telephone entail? Obviously, it is important for the client to reach the right person. Are calls taken within three rings? What is the policy regarding voicemail or messaging? Once management has established its vision of a superior client experience on the telephone, client-facing staff must be coached to adopt and support the system.

What IT systems are needed to put necessary information at your employees’ fingertips when they are speaking on the telephone? What about the use of speakerphones and earpieces? Is the sound quality of telephone calls suffering because employees need to have both hands free to type during calls?

The Client Corridor

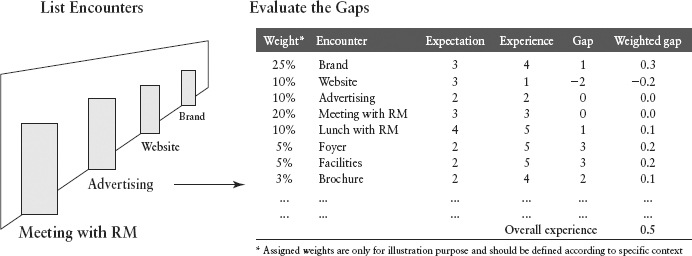

Once we have identified all the touchpoints and considered the gap between expectations and experience, how do we decide where best to invest energy and resources? The client corridor is an advanced model that allows client experience to be visualised and quantified.

The client corridor allows touchpoint interactions to be ordered and examined chronologically. The most frequent and more recent interactions are assigned a higher weighting, reflecting their predominant position within the client’s range of perceptions. This allows for a very effective assignment of priorities when considering gaps between expectations and experience, because it offers insight into the interactions between the various touchpoints. Positive experiences make clients more tolerant of later negative experiences, but only for a limited period of time. The power of the client corridor approach lies in its weighting of every touchpoint interaction. As a result, it is possible to determine which of the 20 percent of these touchpoints drive 80 percent of the experience.

Because the client corridor might not be familiar to all readers, the steps illustrated in the initial stages of the process depicted in Figure 8.4 are described as follows:

- List every interaction between a client and the bank.

- Assign a weighting to each interaction.

- Don’t forget indirect interactions, such as seeing an advertisement or speaking on the telephone:

- Rate the bank’s delivery at each interaction.

- Calculate the gap between expectation and delivery.

Further steps include:

- Multiply the gap by the weighting to identify the touchpoints that most urgently need to be addressed.

- Assign a higher weighting for more recent events. But note that the very first impression should be more heavily weighted than subsequent impressions.

This type of simple exercise can reveal a wealth of detail that a large-scale survey might miss. Private banking is a personal business. It is an art rather than a science. Quite often, observations at the individual level are wasted not because of their seeming insignificance but because we fail to integrate them into the bigger picture. The client corridor is a tool that can be used to gain a better overview of all encounters that might occur between clients and the bank. The client corridor also can be used as the basis for creating internal or external SERVQUAL surveys (see Chapter 9, “Understanding Service Excellence”).

Client Experience Is a Board Commitment

The touchpoints analysis and the client corridor should help to identify areas that require small improvements or even radical changes. The individual priorities in terms of relative importance to client experience should now be clear. Once these have been established, it is possible to create a strategic action plan.

The bank’s board as a whole needs to understand the urgency of client experience and to offer its support. Therefore, a member of the board needs to take ownership in terms of being responsible for the client experience mandate. The client experience team or task force also must develop the strategic action plan to define the practical, organisational, and communications changes required to improve client experience. Budgets should be laid out and approved for each element of the client experience strategy, including everything from rebranding to remodelling interiors to addressing employees’ dress and telephone etiquette.

CONCLUSION

Client experience is a priority for any organisation that wants to hold its own in the increasingly competitive global environment. Technological, social, and market trends have led to rising expectations with regard to quality and personalisation of products and quality. To succeed in this tough market, organisations have to deliver a superior experience that provides clients not just with satisfaction but with true delight. To manage client experience, a touchpoint analysis and a client corridor model can be used to determine the areas where interventions are apt to generate the most value. As client experience consistently must be applied across all touchpoints, there will inevitably be areas where significant investment is necessary. This requires a board member to take the role of “client experience champion.”

NOTES

1. Pine II, B.J. and Gilmore, J.H. 1998. “Welcome to the Experience Economy.” Harvard Business Review (July/Aug).

2. Meyer, C. and Schwager, A. 2007. “Understanding Customer Experience.” Harvard Business Review (Feb).

3. Peppers, D. and Rogers, M. 2005. “Return on Customer Creating Maximum Value From your Scarcest Resource”, Kindle Edition. Crown Business.

4. Rae, J. 2006 Businessweek, “The Importance of Great Customer Experiences” (Nov 27).

5. Discussion with Anthony Lassman: September 5, 2008.

6. 2005. IBM Business Consulting Services and OgilvyOne Worldwide. 20:20 Customer Experience. Forget CRM—Long Live the Customer!

7. Gysi von Wartburg, R. 2010. Finanz und Wirtschaft, Private Banking Wird Virtuell. 5. May. Page 21.

8. Reichheld, F.F. and Sasser, Jr., W.E. 1990., “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services.” Harvard Business Review 68(5).

9. Berman, B. 2005 “How to Delight Your Customer.” California Management Review, 48(1), Fall 2005.

10. Fortune rankings 2010. CNNMoney.com, Fortune.

*The term “customer experience” is a general one used in academic literature to refer to anyone who might use a particular service or product, regardless of the industry involved. In this chapter, “client experience” is the term used to refer to the people who seek the services of professionals at a private bank.

*Beetz, M. 2009. Der Knigge für das Bankgeschäft.

**Jacobs, E. 2010. The Financial Times, “Dress Codes that Suit the Office.”