Chapter 10

Winning the War for Talent

The “people dimension” is the most difficult element to achieve in any service organisation, and private banking is no exception. People in this business require both hard competencies and soft skills. While financial expertise can be learned, soft skills are hard to teach; qualities such as being a good listener as well as being creative and innovative can be developed over time, but they require effort and a high level of curiosity, patience, and human insight. A good balance of hard and soft skills is required in private banking. Beyond finding the right individuals, it is management’s responsibility to leverage on this by assigning the people to the right function. The key question addressed in this chapter is how to attract, develop, and retain talent. While compensation plays an important role in a people business, there are several other factors that contribute to job satisfaction.

WHY THE WAR RAGES ON

Private banking is a people business. People create and deliver the investment opportunities and the client experience it offers. Given the premium positioning of private banking, it is absolutely essential to recruit the best employees and create an environment in which they can excel. This chapter discusses how to attract, develop, and retain the brightest, most talented, and most capable individuals in an industry where dedication and discretion count more than “star” qualities.

Wealth management is a great business. In an unpredictable world where activity is often frenetic and people’s focus tends to be on the here and now, wealth management traditionally has been focused on the long term, projecting values such as stability and calm. Its clients, thanks to having substantial means, enjoy the luxury of thinking more than just a few quarters ahead. They very often think in terms of generations. It is also a highly profitable business when managed properly. Therefore, it attracts a great many competitors vying not only for clients but for the best staff.

In most service industries, employees make all the difference. The expression “war for talent” has been around for several years, gaining traction when in the late 1990s the dotcom boom exploded across Silicon Valley. Established consulting firms suddenly noticed that they were losing some of their brightest young minds to Internet start-ups. The realisation that talent was mobile has in the meantime become entrenched, along with the notion that it is no longer solely the job of human resources to keep valuable employees from leaving. Today, it is the responsibility of the group’s most senior executives to see that retention is implemented systematically and managed effectively to avoid losing top people.

This is true in nearly all industries. With regard to private banking, a rapid expansion in this industry at the start of the new millennium played a major role in bringing the war for talent to private banking business. The growth ambitions of many private banks have led to a need for experienced relationship managers (RMs) beyond what could be supplied quickly from within their own ranks. Thus, the tendency in recent years has been to poach individuals and whole teams from competitors. As might be expected, this practice has led personnel costs to spiral upwards. The war for talent has become a competition for market share and growth and has created a major part of the industry’s cost base.

But even if banks were willing to pay ever-increasing salaries, there is a limit to how often a relationship manager can change employers. Clients want continuity. Furthermore, while the recent boom in the wealth management industry helped to compensate for significant costs associated with hiring, the financial crisis of 2008 and the slowdown in economic growth in most countries has forced private banks to retrench and return to one of the industry’s fundamental strengths: a focus on the long term. Instead of searching for quick solutions to attract talent, the industry must now place even more emphasis on developing and retaining top-notch employees, avoiding a trend that would lead only to higher personnel costs while offering no added value. This chapter looks at the reasons behind the war for talent and how a private bank can prepare for it—in other words, how private banks can attract, develop, and retain the best employees.

In private banking, all business area functions are influenced by an aggressive competition for talent. This is especially the case for highly specialised functions such as product specialists and people filling senior managerial functions. Where the competition is most pronounced, however, is in the hunt for relationship managers. In every growth strategy, the relationship manager is the non-scalable, limiting factor. Therefore, much of this chapter focuses on acquiring and retaining relationship managers.

WHY TALENT IS IN DEMAND

The war for talent rages on in view of numerous factors that are driving the need for relationship managers. Demand for competent and skilled individuals is on the rise in all industries. Demographic factors are shrinking the pool of available managers in established markets as an older generation of relationship managers starts to reach retirement age. Not only is the number of wealthy and affluent clients on the rise; growth in the financial services industry in many cases is outpacing the rate of economic growth, putting private banks into direct competition with each other for candidates to fill new positions. To be effective, meanwhile, a relationship manager can serve only a limited number of clients, given that these clients demand exclusivity and superior service.

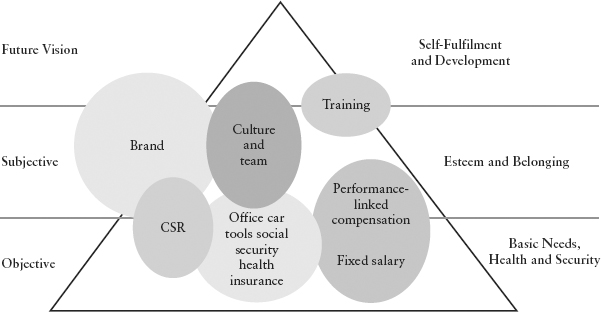

Macro-Factors Include Demographics and Trends in Services

There are various trends putting pressure on the private banking industry in terms of hiring and retention. One is demographics, due to an aging population, and the other is the rapidly expanding demand in many countries for educated staff to fill jobs in the service sector. This latter situation is very much the case in developing countries that are transitioning from industrial to more service-related economies, as Figure 10.1 illustrates. As this occurs, the general level of education in a county rises, expanding the pool of potential recruits for these jobs. But at the same time, as a country’s wealth increases, there also are a greater number of attractive jobs being created in all service-related areas, increasing competition for people to fill these positions. As countries continue to make the shift toward predominantly service economies, the competition across all sectors for the most talented workers will grow. This trend affects all employers, including private banks.

FIGURE 10.1 Changing Structure of Employment during Economic Development

Source: Soubbotina T. P., Sheram K.A. 2000. Beyond Economic Growth: Meeting the Challenges of Global Development. Chapter 9IX, Growth of the Service Sector. © World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/depweb/beyond/beyondco/beg_00.pdf License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 Unported license

Fewer RMs to Meet a Rising Demand for Wealth Managers

As a function of wealth being created, the need for private money managers has grown at a faster rate than that of many underlying economies. In addition, more people are needed in the financial services sector as wealth levels in many countries rise. This puts employers into direct competition not only with firms in other industries, but increasingly with each other as they seek to hire people with the right skills to be relationship managers.

At the same time, the pool of available relationship managers is actually shrinking due to the fact that the entire workforce is aging. The baby boomers born between 1945 and 1965 created a bulge in the 44- to 64-year age bracket. One study in the United States estimated in 2010 that the average age of a financial advisor was just under 49, while less than 25 percent of all financial advisors are under 40.(1) Who will fill their shoes when they retire, something that already is starting to happen?

Not only are relationship managers as a group growing older. Consider Figure 10.2; the number of those in the next working generation is also expected to decline over the coming decades. This age group will form the prime recruitment pool for new managerial talent and RMs in the coming years. Added to this is the fact that the number of potential wealth management clients is rising as the population in the age group over 60 begins to expand over the next decades. Many of the wealthy people in this age group are entrepreneurs who have spent much of their lives building a business. The number of people who have experienced this type of “slow wealth creation”* is growing faster than those who have inherited wealth or acquired their wealth very suddenly. Simply put, the industry faces a situation where the supply of relationship managers is expected to decline just as demand for their services increases.

FIGURE 10.2 Demographic Development of the Population in Europe

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. Available at: http://esa.un.org/wpp/population-pyramids/population-pyramids_absolute.htm Accessed 2012 April 26

The fast pace of growth in the private banking industry, especially in newer markets outside of developed countries, is further increasing the demand for talent. The number of millionaires (calculated in US dollars) in all countries rose by 8.3 percent to 10.9 million individuals in 2010 from 2009, according to the CapGemini Merrill Lynch World Wealth Report. Assets of wealthy individuals grew even faster than the population, increasing by 9.7 percent to $42.7 trillion.(2) The increase in the number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), meaning people with at least US$1 million in investable assets, has been strongest in Asia, including China. But economic expansion in many developing nations, including the other so-called BRIC Countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China—is expected to create new wealth.

To sum up, the need for relationship managers is being driven both by rising demand for skilled employees and by a shrinking population of experienced wealth advisors as the population ages. Compounding the effect, an aging population has a greater need to manage wealth that has been accumulated over the years.

Trusted Advisors Still the Foundation of Relationships

As discussed in Chapter 5, “Putting Clients at the Centre,” wealthy clients’ sophistication has increased, and it is common for them to have multiple banking and advisory relationships. Nonetheless, a long-term relationship with a trusted financial advisor still forms the cornerstone of most clients’ wealth management strategies. While some may take a more hands-on approach,* they still look for an advisor to help them monitor the bigger picture, navigate complex topics, make strategic plans, or guide them through periods of change or transition. What might be thought of as “plain vanilla” investment advice (asset allocation, general tax information, and market coverage) is declining in terms of its significance. Meanwhile, banks are providing more expertise in complex issues of international taxation, asset and income protection, asset/liability management, estate management, or managing the wealth of an entire family (family offices). As the nature of the advisory role changes, an RM must meet client demands that have grown increasingly complex.

Relationship Managers Are Both the Driving and the Limiting Factor

Private banks can try to grow by increasing the “share of wallet” (the client’s assets) held by each relationship manager. Due to the aging population of relationship managers, a new influx of these specialists is required to underpin future growth. The availability of new relationship managers will be the critical factor in determining whether private banks can maintain and grow their market share. The reasons behind this are numerous.

As noted, relationship managers are critical to private banking, given that the essence of what private banking offers is a customised individual relationship. There is a limit to the number of clients an individual relationship manager can support effectively. In private banking, banks need to offer more than just personalised investment advice; they also must be proactive in offering new ideas and solutions for growth or preservation of wealth. This service tailored to the individual is what separates private banks from retail banking and generates the lion’s share of operating costs while also generating the greatest amount of profit. It is difficult for a relationship manager to manage, generally speaking, more than about 100 to 150 clients. If the clients’ needs are very complex, the number might be as small as 50. Given the boom in wealth that began around the time of the new millennium, the number of potential clients has been growing faster than new relationship managers can be recruited and trained; the job requires knowledge of financial markets along with hard-to-acquire “soft” skills and experience.

Therefore, besides market expertise and know-how, relationship managers must possess poise and social competence, communication skills, and a talent for problem solving. A relationship manager needs to have natural sensitivity and the ability to make clients feel at ease. A relationship manager must be able to adopt the right approach, understanding and empathising with clients, bonding with heirs of long-established families and nobility as well as with those who acquired wealth within the space of just a few years or with entrepreneurs well-versed in business and investing. Relationship managers need to be independent, proactive, and focused on finding solutions. Technical and market skills have become increasingly important. At the same time, while functional and technical skills will always be valued and necessary and each relationship manager needs these skills, it is increasingly important to know how to act as an intermediary, bringing together various experts to provide specialised in-house knowledge to the client.

Relationship managers thus do not just need to have their own knowledge but must know where to go or whom to contact to ensure that the client receives the best information and guidance. Relationship managers also need to be able to network to meet new clients and must constantly be pursuing fresh leads. They need to be talented in managing time and able to coordinate and cooperate with a team of experts while possessing confident presentation skills. This type of knowledge is acquired through years of experience in the business.

WEAPONS TO WIN THE WAR FOR TALENT

The previous section examined reasons why there is a war for talent. Due to shifting demographics and continued growth of HNWI wealth, including in emerging markets, the war for talent will continue, if not intensify. The following section looks at “weapons” that can be used to win that war.

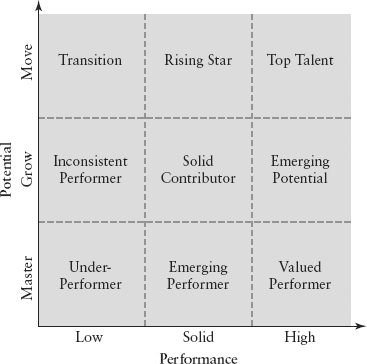

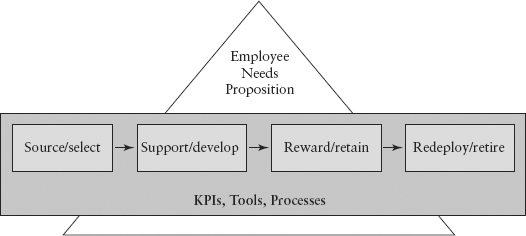

Going into battle is never cheap. In private banking, whether one develops in-house talent or aims to attract specialists from other players, those engaged in this battle must be prepared to invest for the long haul and in sizeable amounts. But this is just the start. To really win the war for talent, it also is necessary to think about developing, retaining, and, on occasion, terminating employees. One way to look at all the elements of human resources strategy is through the “employee needs proposition.”

Attracting Talent

Chapter 8, “Delivering a Superior Client Experience,” discusses how clients interact with the brand via so-called touchpoints and how these can be analysed using a “client corridor.” We can apply the same principles to the process of attracting new talent. The employee needs proposition is a useful tool that brings together all the factors that contribute to this aim. Every encounter between a potential candidate and the bank is a touchpoint, which should be systematically analysed using an approach that evaluates gaps between expectations and actual experience. Consider the impression the bank makes on potential candidates with its branding, public relations, or marketing. Recall the atmosphere of the interviews conducted during candidate evaluations. Do the interviews truly embody the brand values and really inspire candidates to desire to join the bank?

Businesses have grown accustomed to the concept of the customer value proposition as a way of keeping customers loyal. In a similar way, the employee needs proposition blends objective and subjective criteria applied to employees’ needs and aspirations.

The pyramid in Figure 10.3 is similar to one depicted in Chapter 7, “Why Brand Matters,” and is based on US psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. The same structure can be used to organise the elements of what is commonly referred to as the employee value proposition*—here represented as the employee needs proposition. On the right is the hierarchy of human needs as determined by Maslow. On the left are “perceptual” categories: objective, subjective, and future vision.

Incentives are positioned according to the needs they meet. Some corporate elements, such as “brand,” extend outside the pyramid because these are much bigger than what could be encompassed in a single employee contract. Similarly, some employee incentives also extend outside the pyramid, as employees can pursue training not only on the job but also independently, though an employer may offer in-house modules or provide support individuals who pursue a doctorate or a master’s degree in business, for example.

The pay package must take into consideration basic needs, reflecting the right balance between risk and reward. Incentives and performance management should be appropriate for all functions. While a fixed salary covers an employee’s basic needs, performance-related compensation can be viewed as a way to satisfy esteem and self-affirmation. In addition there are the higher needs including self-fulfilment and corporate responsibility, along with social responsibility at the top of the pyramid. These cannot be satisfied with more money, but serve as an example of how an employer also may provide avenues to achieve these goals.

Having established the employee needs proposition framework as the basis for attracting and retaining employees, it is important to consider the steps involved in the employee life cycle—sourcing, recruiting, supporting/developing, and retaining, along with eventual retirement or, if necessary, termination.

Sourcing Talent

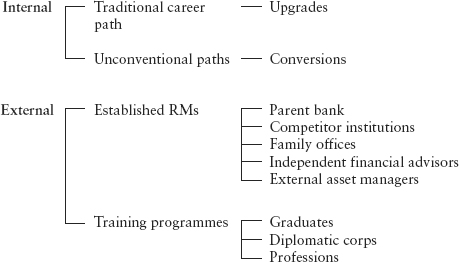

A private bank needs to have many types of employees: senior management and relationship managers; product specialists; and technical, operational, and support staff. While those in the latter categories can be recruited and chosen as would be the case for any position in financial services, it is different in the case of senior management and relationship managers. These people rarely apply to a bank; instead, they are usually approached. The potential sources of talent come from two main pools: internal and external, as shown in Figure 10.4.

Internal recruits may have traditional career paths, meaning the conventional route to become a relationship manager taken by graduates who enter banking. Less conventional is the path of employees in other professions within the bank, such as lawyers or economists, who switch during their career and become relationship managers. External candidates can be recruited via a formal training programme such as graduate recruitment, or they can be established relationship managers working elsewhere.

Within these pools of talent, how does one start looking? One important source is networking. Switzerland’s wealth management industry is a close-knit community. Within the country, it is possible to know everyone considered to be “someone” in the industry. The key is to identify potential candidates based on their current profiles or performance and their experience in a particular field or region. Once a detailed database of contacts is established, it is possible to fill a large number of positions without ever having to resort to a head-hunter or a job advertised through public media. Recall the theory that it is possible to connect with any person on the planet through only six intermediary steps.* Put that principle into practice, and you can usually approach a candidate fairly effectively through existing contacts. But it also makes sense to look for potential relationship managers internally before becoming involved in a costly external recruiting process. The main motivations to externally source relationship managers are experience, networks, and client portfolios. When a relationship manager retires, that also is an opportunity to promote new talent from within the bank; lawyers, product designers, assistants, and project team leaders, for example, can become successful and profitable relationship managers given that they have the right personality and receive the appropriate training and mentoring. The advantage of cultivating internal candidates is that they are already very familiar with the bank’s culture, processes, and procedures, while generally being more loyal than those brought in from the outside, hence reducing future acquisition costs.

Recruitment Practices

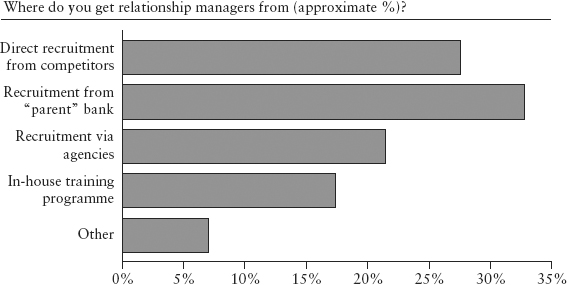

The industry’s long-term growth depends on developing new talent, including through internal channels. But the immediate growth needs can often be met only via external recruitment. Private banks, according to one survey by Oliver Wyman, may meet over 80 percent of the need for new relationship managers through “outside” hires, including from the parent organisation.(3) Based on data represented in Figure 10.5, about one-third of relationship managers are recruited through the parent bank, and more than one-quarter directly from competitors. Fewer come from in-house training. Other sources might include agencies, noncompeting financial institutions, the professions, other industries, and even diplomatic circles.

FIGURE 10.5 Recruiting Client Relationship Managers

Source: Oliver Wyman Financial Services, “Wealth Management Strategies for Success.” 2006

When recruiting from competitors, private banks may hire individuals or whole teams. For the hiring bank, teams are in many respects a much better proposition. Teams, unlike individuals, usually take a higher proportion of their clients with them when they move. By contrast, if a relationship manager leaves on his or her own, other team members can intervene to reduce migration losses, because the team usually has long-standing arrangements to cover absences and holidays, in effect allowing all members to develop relationships with clients. On the other hand, when a whole team is recruited, this can pose a greater integration challenge to the bank doing the hiring.

Where back-office and support staff are concerned, there are fewer ground rules. In the past, anyone with solid retail or universal bank experience would do just as well as someone with specific private banking experience. Nowadays, however, due to the importance of brand positioning, these jobs also require a high degree of loyalty and a service-minded approach. One can draw inspiration from the recruitment approaches taken by companies known to be premium providers in their industry, including those outside of banking. Whatever function is involved, a private bank needs to hire the best possible candidates, not only in terms of qualifications and talent but also through seeking people with above-average motivation, strong identification with the brand, and the ability to be flexible.

Supporting and Developing Talent

Supporting and developing talent is important. The following section discusses why future growth and a desire to be cost-effective require every institution in the industry to take responsibility for training individuals, rather than simply hiring “ready-made” talent. Once employees’ basic needs have been met, the focus is on development. This is particularly important with regard to candidates for relationship manager or managerial positions. A bank needs to include development and growth opportunities as part of its goal of satisfying employees’ needs, including the more abstract ones outlined by the employee needs proposition.

One way to start is with an assessment of an employee’s long-term goals. If he or she starts a career in the product department, what would the person have to do to develop the skills needed to become a relationship manager? If someone is an assistant relationship manager, how long will it take until he or she is promoted? These questions can be answered through a career path “framework.” By communicating the career path framework explicitly, the bank can express its commitment to an individual’s development and reduce career-motivated departures.

Conferences, seminars, and intensive workshops are vital in order to induct an employee into the bank’s culture, especially during the first 100 days. These platforms remain important throughout an employee’s career. Larger banks such as UBS are able to maintain dedicated training and development programmes, such as those held at its Wolfsberg centre. (See box.) But it need not be a physical facility. Some banks offer online training as well as a virtual classroom and specific courses and events to achieve the same purpose without the fixed costs of maintaining an elaborate centre.

What about “stars”? In fact, in private banking teamwork is perhaps the most important element in supporting talent, as opposed to cultivating an individual star culture. In 2001, Stanford University business professor Jeffrey Pfeffer published a study entitled “Fighting the War for Talent Is Hazardous to Your Organization’s Health.”(4) In it, Pfeffer argues against allocating too many resources toward attracting and retaining star performers, because rewarding individual stars tends to diminish teamwork. Instead, it can lead to destructive internal competition and downplay skills of insiders while glorifying the talent of outsiders. This reduces motivation and ultimately leads to an elitist, arrogant attitude. Pfeffer writes that the particular emphasis on the individual at the expense of the team is “almost an inevitable outcome of a war for talent mindset,” while companies overlook the fact that “it is often the case that effective teams outperform even more talented collections of individuals.” In private banking, it is the management practices and culture of the company as a whole, as opposed to the flair and star qualities of a single individual, that will determine whether a relationship manager’s efforts translate into lasting added value for all stakeholders. If the attitude driving the war for talent includes the assumption that a company’s performance is nothing but the aggregate of individual performances, and an adult’s learning potential is limited, one can agree. But if one believes strongly in attracting the best talent and building on strengths rather than trying to eradicate weaknesses, a valid argument can still be made for talented people to be cultivated in an organisation while ensuring that these people also work well within a team.

Retaining Talents

Retention is more critical in wealth management than in many other industries, because a departing senior relationship manager can take a portion of the portfolio (meaning clients) when he or she leaves. Should this happen, in addition to losing clients, potential future referrals, assets, and revenue, the bank must face fresh acquisition and development costs. So how does one avoid losing employees to a competitor if a competitor makes them a better offer?

First, it is necessary to understand what is meant by a “better offer.” Usually this refers to more lucrative compensation or increased responsibility. However, many other factors are likely to be involved; human resources specialists often say that an employee joins a company but leaves a boss. In other words, the company’s image and the employee needs proposition can attract talent, but the human chemistry and the atmosphere at work will strongly influence whether or not a person stays.

Therefore, good teamwork is critical to retention. Managers must be close to their staff, listening, supporting, and developing skills and talent. In private banking, many banks are now trying to put the emphasis on being a trusted firm, focusing on teamwork rather than seeking to attract and retain clients solely on the basis of single advisors. Relying on the skills of a number of individuals within a team also provides a higher quality of advice on specific issues, all the more important in an increasingly complex world where no individual can possibly be an expert in all fields. Rather than simply encouraging the client and relationship manager to bond, involving an entire team, both the client and the relationship manager bond with the bank.

The quality of support offered to relationship managers contributes to retention and to client satisfaction. Support for relationship managers could include, for example, dedicated groups that operate in-house to help them meet clients’ needs. Ideally the all-round support given to a relationship manager should enable him or her to deliver a superior client experience and level of advice that would be difficult to replicate at another company. Even so, for many clients the relationship manager is still more important than the institution. A survey conducted by the VIP Forum published in 2004 found that only 30 percent of HNWI clients saw the institution as more important than the advisor.(7) However, these findings also indicate that there is ample scope for private banks to enhance the ties between clients and banks.

In terms of compensation, various approaches may be used. Non–client-facing staff usually receive compensation based on a discretionary model tied to objective principles. Relationship managers traditionally receive a base salary and bonus. Increasingly, the bonus has been based on profit contribution models (the profit earned by the individual, his or her unit, and the bank as a whole).

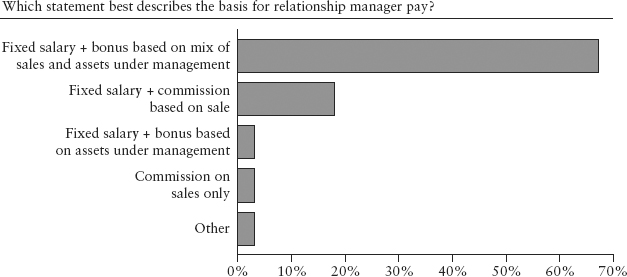

Figure 10.6, based on a study by Oliver Wyman (2006 study), shows that nearly 70 percent of relationship managers received compensation consisting of a fixed salary and bonus based on a combination of sales and assets under management.(8) This represents a good compromise between the interests of the bank and its clients; other alternatives might be less satisfactory. For example, arrangements paying relationship managers a fixed salary and commissions could tempt relationship managers to “oversell” transactions. On the other hand, the smaller percentage of relationship managers who earn a bonus related solely to assets under management might in turn be tempted to focus on increasing deposits at the expense of performance.

FIGURE 10.6 Remuneration of Client Relationship Managers in Europe

Source: Oliver Wyman Financial Services, “Wealth Management Strategies for Success.” 2006

The crisis in financial markets in 2008 heightened public awareness of the bonus culture in banks. Although payment of very large bonuses is a practice more common at investment banks than in private banking, a debate continues on how to best align incentives with risk, including at private banks. In addition to the basic salary and bonus elements, some banks may also offer stock and stock options as additional incentives. However, wealth management firms most often use longer vesting periods than other financial firms to increase retention. Many firms are considering adopting longer vesting periods to encourage employee loyalty and add an incentive for staff to act in their clients’ best long-term interests, hence in the bank’s own interests as well. At the same time, employees usually prefer shorter vesting periods. So both sides of the equation must be carefully evaluated. Multi-year bonuses are becoming increasingly common, meaning the bonuses are tied to performance over several years. One should note that relationship managers who spend their careers seeking to accumulate wealth for clients might be expected to look after their own interests. At the level of the individual relationship manager, it is therefore wise to balance incentives and use a granular approach to profit-and-loss accounting. This can be achieved by taking into consideration full costs per relationship manager, not just revenues after direct costs. Furthermore, any formula-based compensation model needs to be thoroughly tested in different market performance scenarios before being rolled out.

When deciding which benefits to offer, human resource executives at private banks should look beyond the traditional offerings and consider what can be done to heighten the sense of community, increase pride in the brand, encourage good corporate citizenship and teamwork, and enhance employee loyalty. When an employee’s basic salary is sufficient to cover the bottom layer of needs on Maslow’s pyramid, other considerations come to the fore, such as reputation, professional titles, education, and career development plans. These incentives are more significant than earning a little more or paying slightly less tax. The employee needs proposition introduced earlier in this chapter offers some insights into how the different needs might be grouped and aligned with company’s aims.

Termination and Retirement

Some companies, particularly in North America, apply a “pruning” strategy to their staff and fire the lowest-performing 5 percent of their relationship managers each year. In Europe, this practice is not widespread. It is common to terminate employees who do not perform or meet targets but not on the basis of any numerical quotas. One should always measure an individual’s performance against that person’s personal business plan and within the context of the market.

That said, a private bank needs to have some kind of termination policy to avoid spending a disproportionate amount of energy helping a struggling minority rather than strengthening the competent majority. Although reviews typically take place on a quarterly basis, it is difficult to judge an individual relationship manager’s performance over a span of less than 12 months. So it is unwise to make rash judgements regarding what simply might be a temporary period of subpar performance or bad luck.

Many private banks are keen to retain the skills and resources of good relationship managers beyond retirement. This trend will become even more pronounced in the future due to the demographic developments described earlier in this chapter. There are a number of solutions and models for compensation. One solution would be to simply delay the inevitable—in other words, to put off retirement. A wiser strategy, however, is to successively transition these employees; an older relationship manager can hand over his or her portfolio in stages to a younger colleague, while mentoring and supporting more junior relationship managers, thus remaining available to clients and the company as a consultant until entering formal retirement.

MEASURING YOUR SUCCESS: THE HR TOOLKIT

The employee needs proposition is the key to developing an effective strategy for human resources. This section deals with the practical aspects by examining the processes, tools, and key performance indicators (KPIs)—quantifiable measurements used to evaluate the success of a particular activity—employed to win the war for talent.

As in every area of the bank, human resources needs to be led by so-called management by objectives (MBO) principles, which means setting goals with the individual employee that reflect the bank’s overall goals. These goals shall then guide all of the employee’s actions and decision making at work and serve as the benchmark during performance appraisals. Figure 10.7 shows the four stages of the employee life cycle: source and select, support and develop, reward and retain, and finally, redeploy or retire. Notice the employee needs proposition in the background, which affects all these stages. Let us now look at the approaches, tools, processes, and key performance indicators needed to implement the strategy and to set and monitor objectives.

FIGURE 10.7 The Human Resources Life Cycle: How the Employee Needs Proposition Applies to the Initial Phase and Subsequent Three Main Phases

Source: Julius Baer

Source and Select

Sourcing and selecting requires structured processes and a number of key performance indicators. These are described in detail in the following section.

Sourcing Candidates

This chapter already has touched on the advantages of using a networking approach to sourcing candidates.

What are the practical steps to adopt to build on this approach? One way is to create the central database mentioned earlier, a “Who’s Who” of relationship managers. Human resources should note previous positions, current employer, track record, and areas of expertise of all the professionals with whom the bank’s employees regularly come into contact. It is amazing how much information can be collected over time after a suitable repository has been created and an orderly work flow process established.

Once such a database is set up, the bank can identify possible candidates. There might be two forces at work denoted as “push” and “pull.” Push refers to cases in which a relationship manager initiates contact or shows a strong readiness to change his or her employer. This is very uncommon, however, unless the institution where the relationship manager is currently employed is facing difficulties. The more usual scenario is a pull situation whereby the initiative comes entirely from the bank seeking to hire.

A recruiting bank should analyse all factors affecting a relationship manager’s push and pull situations carefully. A relationship manager can switch banks only a few times during a career, due to the undesirable impression of instability that this creates for clients. So he or she must carefully consider any new position and time job moves very carefully. In a pull situation, the bank needs to offer the candidate a strong employee needs proposition.

Selecting Candidates

The first requirement for tools used by human resources departments is that they must provide a structured approach for writing job descriptions. This means getting the relevant information from line managers regarding the specific demands of the job and then formulating and updating the description. This document serves as the basis for the recruitment advertisement and the interview and job performance evaluation; the better the job description, the easier it will be to do the rest. It is a good idea to create a checklist to ensure that all relevant managers and staff have contributed to writing the job description and to engage the help of an expert to make it into a polished advertisement.

The next step is to appoint an interview guide to cover all the essential areas, including job knowledge, personal and career background, situational issues, or current circumstances, and finally, to conduct personality profiling and check the candidate’s character references.

The interview guide must communicate clearly with no ambiguities so that the interviewer understands exactly what information is needed to assess whether the candidate is suitable for the position. In order to match the level of the interview to the level of the position, human resources should work with the line manager to determine the questions to be asked about a candidate’s knowledge as it bears on the job. It is also recommended that interviewers be clear on the importance of having a personal set of standard questions to ask each candidate so as to involve the interviewer more directly in the process. In order to make it easier to rate candidates, a bank can draw up a list of plausible answers for each question and then assign a score to candidates’ answers. Obviously all these tools will bring consistent results only if the interviewers are trained in using them.

When discussing recruitment, it is common to think of it in terms of finding the right person for the job. But in fact, the process would be better served if it were viewed as posing two potential dangers: not hiring the right person or hiring the wrong person. These can be expressed as Type I and Type II errors. While it soon becomes apparent when the wrong person is hired, it is nearly impossible to know when the right candidate has fallen through the net. In the former case, one can try to track the false positives when candidates turn out to be unsuitable and then analyse the interview process to see what signals were missed. This type of tacit knowledge, skill, or experience, however, is difficult to document or quantify.

For this reason, human resources specialists should be involved in the interviews to support the line manager. But this requires clear feedback from the line manager about the candidate, both during the selection process and after it is completed. This feedback is also crucial for refining the hiring process. In senior-level positions, where it is extremely important to ensure that there will be no clashes in terms of corporate culture, the head of the bank should be able to interview and veto any appointments. Even though human resources and line managers are trusted in matters of competence, the CEO needs to ensure that the candidate will be able to embrace the organisation’s culture and bond with the management team.

Key Performance Indicators in Recruitment

Here are some useful measures that might be applied as key performance indicators, which should be regularly reviewed and analysed:

- Recruitment cost per employee. This is the sum of the fees required to advertise jobs, executive search agency fees, employee and referral finders’ fees, travel expenses, relocation expenses, payments to internal recruiters, and sign-on bonuses. These should be established for RMs and for other types of employees separately. It is important to monitor the relative weighting of the various cost elements in this process.

- Time to fill. This refers to the time needed to fill the position. If you use this as a part of a management by objectives’ compensation model for human resources, it also is essential to consider the “time to start.” It does little good if your human resources department finds a suitable hire quickly, only to have this person be unable to start work for a long time due to notice periods and “gardening leave.”*

- Recruitment pipeline. There are a number of ways to evaluate the recruitment pipeline. These include tracking the number of open positions, the number of employees screened, and the job acceptance rate. Together, these indicate how competitive the bank’s offers are and gauge the recruitment procedure’s efficiency. Note that a low acceptance rate does not always mean the package was unattractive. Sometimes candidates have no real interest in the job. They simply want a benchmark or assessment of their current market value to use when negotiating compensation vis-à-vis their current employer.

- Number of early departures (for example, after one year of hire). A high number may indicate that something went wrong during the recruitment process; either new hires were not right for the positions (Type I error) or the positions did not match the new hires’ expectations (a communication gap during hiring).

Support and Develop Employees

A structured approach is needed for the first months after a new employee joins the company. He or she must be immersed in the corporate culture to become fully acquainted with company’s values and how the bank puts them into practice in daily business. Sufficient guidance should be provided for training, administrative issues, and where to go for information. It is also important to get feedback from new employees after the first 100 days in the job to learn how the “indoctrination” process went. This information can be used to improve the process for future new employees.

But the process doesn’t stop after the first three months. The bank needs to deliver on the promises spelled out in the employee needs proposition made during recruitment and throughout the tenure. This is best done by defining and implementing an explicit development strategy for employees, based on the following tools and processes:

- Specific, explicit career path frameworks. These give employees an overview of steps required to take control of their careers while giving them a clear time horizon.*

- Structured learning or training, targeting clear and distinct groups. When creating an employee development strategy it is important to evaluate internal and external training options, deciding what to offer in-house and what to outsource.

- Management involvement and management development. Managers need to be responsible for the members of their team but also need to encourage employees to become managers by offering opportunities to develop the 360-degree perspective and interpersonal skills that a management position requires.

- Management by objectives. Set clear objectives at the beginning of the year and then evaluate whether employees have achieved the goals when performance appraisals are done at the end of the year. Use a rating for each objective and link it to compensation and training opportunities.

- Succession planning. The CEO needs to manage a leadership pipeline that will create the next generation of leaders and executive board members.

Key Performance Indicators in Development

- Performance differential. One way to calculated this is to compare the new employee’s performance and the performance of an established employee taken as a benchmark.

- Time to portfolio. This reflects the time it takes for a new relationship manager to build a portfolio that begins to cover the investment made by the bank in hiring that particular relationship manager. This is one of the critical cost issues involved when hiring relationship managers. On the basis of estimates and personal experience, it takes a relationship manager about one year to build a portfolio that will cover direct costs because of the time needed to acquire clients and transfer existing client portfolios.

- Training and development costs per employee. This includes all costs related to internal and external education of an employee that were covered by the employer over a specific period. An average training and development cost per employee can then be calculated across the entire bank in order to compare it to previous years or external benchmarks. Alternatively an average can also be calculated per department in the bank in order to benchmark departments against each other departments.

- Training quota. This refers to the percentage of employees receiving training.

- Turnover due to career development issues. This might include employees who decide to change jobs because they could not satisfy their ambitions in their current job.

Reward and Retention

Further tools and processes should be implemented to develop the reward and retention stage of the human resources strategy include:

- Specific competency profiles and job-function benchmarks. These provide an easier way to make objective decisions regarding recruiting and terminating.

- Compensation benchmarking. This allows for comparisons to be made with competitors and should be done on a regular basis.

- Formula-based compensation. This approach is being revolutionised by regulations introduced in the wake of the financial crisis. Besides linking net new money and revenues to the direct costs arising from individuals, banks also need to consider risks and withhold compensation until a relationship manager’s activities show they have created lasting value.

- Benchmarks linked to geographical regions. Such benchmarks can be used to build compensation models, which should help to prevent any bias favouring rapidly expanding markets. It may be easier for relationship managers to attract new money in such regions, but banks shoulder more cost and risk in these markets.

- Diversity management. Diversity means more than being simply “politically correct.” A mix of gender, nationality, and age in the workforce can create a more creative environment where new ideas flourish and the bank is more open to change. Such a workforce is certainly easier to lead when a bank wishes to go in new directions or access new markets.

Key Performance Indicators in Reward and Retention

- Average tenure. Under normal circumstances, average tenure is a good measure of retention success. However, any changes to the rate of recruitment will distort this indicator. For example, at Bank Julius Baer there was a period when average tenure was dropping radically every quarter; rather than being caused by defections, it was due to a steady recruitment process. At one point during this period, almost one-quarter of the employees at the bank had been with the company for less than one month. That was an extreme challenge for training and cultural integration. The figure then dropped from 23 percent to 20 percent in the following 12 months as the expansion phase tapered off.

- Average absences and the holiday balance. These are more finely grained indicators of employee well-being than length of tenure. They also give indications of individual and departmental workloads and motivation levels. In private banking, the balance of unused holiday entitlements are generally higher than in other industries and doctor-approved absences are below average. These are indicators of a motivated staff working in a fast-paced, high pressure environment.

- Turnover arising from compensation and benefit issues. This may indicate that compensation is not competitive relative to the market.

Redeploy, Retire, or Terminate

No human resources strategy is complete without a policy for redeployment, retirement, and termination. Using the information gathered in the course of the activities described, it is possible to establish a “human capital portfolio”—an overview of each employee’s career.

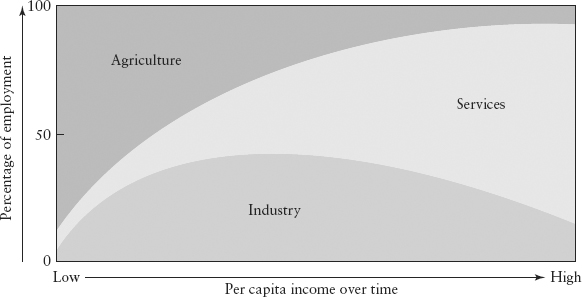

Even though human resources is a “people” business, a matrix as represented in Figure 10.8 based on each employee’s current performance (X-axis) and development potential (Y-axis) helps to provide an objective overview of that employee’s positioning in terms of career performance and goals. This makes it easier when determining which employees should be promoted, which ones need time to grow, and which ones should be let go. A bank can also map the positions of whole departments or teams in this way.

With that in mind, one can consider the best key performance indicators to use when evaluating performance.

Key Performance Indicators in Employee Turnover

- Turnover rates. Zero turnover is not necessarily a good sign. New people bring fresh impulse and ideas and encourage increased efficiency. A better measure may be to compare turnover rates with those of peers.

- Termination versus resignation. In regard to resignations, these two conditions must be differentiated. There are staff whose departure is regretted and those where a departure was viewed as best for the employee and/or the employer.

- Track nonperformers. With regard to relationship managers, it is best to keep track record of performance metrics such as net new money, return on assets, and assets under management. In terms of a bell curve, compare the individual metrics with the distribution of those across the entire bank. Is the individual’s curve a normal bell with a solid middle and an even spread of top and poor performers? Or are extremely good or bad performances skewing the picture?

- Record keeping. It may also be useful to keep a record of why people leave the firm and track the frequency of various factors influencing the decisions—for example, if many employees move to the same competitor, or if a number of them cite the same reason for departure (salary, “bad chemistry” with a superior, or other factors). Companies should keep a record of where people tend to move and consider whether or not to adopt or emulate these companies’ hiring or compensation practices.

CONCLUSION

The war for talent is a fact—an inevitable consequence of major changes affecting an industry in which individual companies must increasingly compete for employees. Demographics and economic developments are contributing to this trend. Despite the financial market crisis in 2008 and the ensuing recession in many countries, the fundamental dynamics of the war for talent have not changed. Wealthy people will still seek the services of trusted firms and advisors who take a long-term view toward managing assets. Bank collapses and redundancies have led to what banks might consider more “reasonable” compensation demands. But companies also have used downsizing as an opportunity to shed weaker performers, leading to a further concentration of highly qualified individuals to fill positions. The war for talent continues, albeit sometimes with different tactics.

A private bank needs to hire the best possible candidates in terms of qualifications and expertise—people with above-average motivation, brand identification, and flexibility. This does not contradict the importance of teamwork or suggest that adults have limited potential to learn new skills. Hiring the best candidates is simply akin to securing the pole position in the starting grid, meaning even with other factors being equal, the company is placed in an advantageous position.

Given wealth managers’ oft-repeated claim that theirs is a long-term business, market downturns offer them an advantage to attract potential talent at fair prices while investing in support and development. This will pay dividends over time, benefiting not just a single bank but the industry as a whole.

In periods when resources are less freely available, a bank can still fight the war for talent by paying extra attention to higher-level needs and by offering subjective incentives. These include strengthening the brand and ensuring that employees receive the esteem and affirmation they need, while providing career development opportunities. It is also essential that management communicates a strong vision for the future, while remaining close to individual employees.

NOTES

1. Cerulli Associates, The Cerulli Edge Advisor Edition – “Hire Train or Else.” Q3 2010. Quoted in: Jeff Schlegel, “Opening the Doors,” Financial Advisor Magazine, December 2010.

2. Capgemini Merrill Lynch Wealth Management. 2011. World Wealth Report 2010.

3. Oliver Wyman. 2006. Financial Services: “Wealth Management Strategies for Success.”

4. Pfeffer, J. 2001. Research Paper Series Graduate School Of Business. Stanford University. Research Paper No. 1687.

5. Stäheli, C. Wolfsberg. 2008. “The Platform for Executive & Business Development.” Schloss Wolfsberg bei Ermatingen. Die Schweizerischen Kunstführer GSK.

6. Business School Jahresbericht. 2010. Credit Suisse

7. VIP Forum. 2004. “Organizing for Sales Effectiveness.”

8. Oliver Wyman. (See note 3.)

*See Chapter 5, “Putting Clients at the Centre,” for a discussion of wealth creation.

*See Chapter 3, “Finding the Right Organisation and Operational Strategy,” for further information about why clients have become more active in managing their assets.

*The pyramid in Figure 10.3 resembles the needs hierarchy developed by Abraham Maslow, as applied to branding. The same structure can be adapted to show elements of the employee value proposition (EVP) included in the book War for Talent published in 2001, based on a landmark 1997 McKinsey study. When these concepts are combined, the result is the employee needs proposition (ENP), a concept developed by this book’s author.

*The idea that all humans on the planet are separated by a constant number of “degrees of separation” is a theme that has been discussed and investigated by various studies. The result of an experiment by Stanley Milgram and Jeffrey Travers conducted in 1969 in the United States involved sending letters to people, who were then requested to pass along a letter to a certain stockbroker in Boston. If they did not know the person, they were asked to pass the message instead to someone they knew, who, they believed, might have a better chance of being acquainted with the broker. On average, six people served as intermediaries until the broker got the message. A more recent separate study by Microsoft that analysed billions of emails calculated the separation at closer to 6.6 degrees. Original Source: Travers, Jeffrey and Stanley Milgram. 1969, “An Experimental Study of the Small World Problem.” Sociometry, 32(4), pp. 425–443. The information about Microsoft came from media including a report published by the BBC News (2008 Aug. 3 “Study Revives Six Degrees Theory”).

*“Gardening leave” describes a situation in which an employee gives notice and vacates a position but after leaving the old employer is barred from starting the new job for a set number of months. This practice is designed to prevent the new employer from gaining an unfair advantage through information or contacts obtained from recent hires.

*For example, determining which interim positions might be required and what training must be completed for an employee to become a candidate for the position of Head of Treasury.