Chapter 9

Understanding Service Excellence

For a chief operating officer who is overseeing internal service-oriented units, service excellence should be one of his or her top three priorities. For financial services firms, service, as the name suggests, is key. It is important to foster a strong bank internal service culture along the entire value chain. It is important to see this culture as starting within the organisation, not something that matters only for external clients. To assess the level of service quality, it is very useful to conduct surveys that go beyond absolute values to capture the “gaps”—in other words, the quality of service as it is perceived and the actual level of service delivery. It is also important to remember that surveys are just one tool. A company must live its service culture, starting with senior management.

SERVICE EXCELLENCE AND THE INTERNAL CLIENT

Service excellence can be defined as the level at which service exceeds the needs and expectations of the customer. In the context of private banking, most people would assume that service excellence describes a situation whereby wealth managers are required to fully understand the client’s investment needs and expectations and provide superior advice while implementing the steps required to ensure quality standards are met. But there is another way to think of service excellence, in which the focus is directed not on clients but on a bank’s own employees—that is, service excellence applied to the internal service processes within a bank. This includes promoting a culture that enables employees to deliver a superior result to clients in a manner outlined elsewhere in this book as “client experience.”*

Using this approach puts the focus on services and their “excellence” in terms of how these are provided to the bank’s “internal clients.” After all, a client is anyone to whom a service is rendered. And a private bank cannot aspire to be excellent in its approach to external clients if it doesn’t have an internal culture of service excellence. If a private bank can inspire service excellence within its ranks, then and only then does it have a chance of delivering a top client experience. This chapter looks at what is meant by service excellence and its importance to the overall business, as well as ways to ensure it continues to be upheld. It then goes into specific areas in terms of four key elements that are used to obtain and maintain service excellence. Finally, it delves into the means to objectively measure whether the desired level of service excellence is met and how to meet the specific targets to achieve this.

Practitioners of the art of private banking and various academics have spent both time and energy delving into the subject of service excellence. It is a popular topic. There are even awards for service excellence and related training courses. The majority of organisations, at least large ones looking to the future, believe they already have initiatives in place aimed at fostering service excellence and that they deliver it. Based on surveys, however, most people struggle to offer an example of an organisation that really delivers on its promise to provide service excellence.

Why is achieving service excellence such an elusive goal? Most services are intangible, things that cannot easily be measured or objectively assessed; often, they consist of single actions finished before they are even consciously registered by the person receiving them. In private banking, the perception of how services are delivered depends solely on the interaction between the provider and the client, making service excellence a difficult concept to assess. Similarly, “excellence” constitutes a veritable end of the rainbow, something forever pursued but never quite reached. While striving to obtain service excellence, it is important to take a close look at the employees, culture, tools, and processes involved, continually asking how the parameters can be altered to encourage both internal and ultimately external service excellence.

DEFINING THE INTERNAL CLIENT

Getting a sense of what is meant by an “internal client” is crucial in order to understand the concepts presented in this chapter. The simplest way is to use the following exercise:

Close your eyes and imagine for a moment that you are an employee and you have decided to leave your firm. Your boss does not want to let you go, but at the same time respects your desire to work from home. So he or she asks you to do exactly the same job on a freelance basis. You agree. Your former employer and colleagues become your clients. Your tasks remain the same, but your attitude is now different. You have a client. Everything you know about satisfying the client suddenly comes into play. It becomes clear that you need to be exceptional to stay in business. You are more willing to start going the extra mile. At the same time, you have been empowered. Taking ownership of your own business has filled you with a sense of responsibility and pride.

One consequence of thinking this way is that the same principles of service excellence can be applied, regardless of whether an internal client (employee) or an external client is involved, especially because internal client satisfaction forms the foundation for external client satisfaction. This notion was first widely explored in a study published in the United States in 1994 in the Harvard Business Review, which is discussed in the following section.

THE SERVICE VALUE CYCLE

Internal service excellence plays a vital role in a company’s success. Achieving genuine internal excellence results in happier and more motivated employees, and the level of employee satisfaction and motivation has been shown by numerous studies to be highly correlated with client satisfaction. This in turn affects the results of a business over the longer term. It also is wise to remember that front-line staff (those in direct contact with clients) rely not on just a few, but on all the internal processes within a company to deliver the qualities promised by the brand. So what is true for individuals is true for all employees, and all must be included in the process.

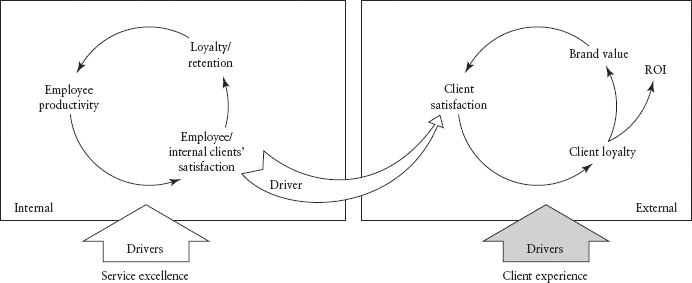

The study in the Harvard Business Review that highlighted the importance of this way of thinking, “Putting the Service-Profit Chain to Work,” examined how employee satisfaction directly and indirectly drives customer satisfaction, which in turn influences brand reputation and profitability.(1) A diagram such as the one shown in Figure 9.1 can be used to illustrate how employee satisfaction may directly influence client satisfaction.

In Figure 9.1, the positive feedback loops for both employees and clients are illustrated as two virtuous circles that are interconnected. Internal service excellence within a company (left) helps drive client experience (right). In the “client experience drivers” on the right, brand value is perhaps the single most crucial element in terms of reinforcing client satisfaction. And, as Figure 9.1 shows, increased return on investment (ROI) resulting from client satisfaction is a derivative benefit that allows growth and further investment in the two main drivers, service excellence and client experience. Most of all, it is important to note the key role employees play in delivering the client experience. The service excellence drivers provide the means for employees to perform their jobs well and are coupled with appropriate motivations to increase productivity, loyalty, and satisfaction, reinforcing the desired effect within a “positive feedback loop.”

Most authors of studies on business management do not include employee loyalty in their discussion of the service value chain, but it is certainly worth looking at it as a separate category within the larger discussion of what contributes to service excellence. Whereas employee satisfaction can be considered a temporary state, loyalty is a more important long-term attribute that is essential in bringing employees through difficult periods when satisfaction is not immediately forthcoming. Loyalty was extremely important, for example, during the financial crisis of 2008. During that difficult period, employees were placed under tremendous strain (and many also feared for their jobs and the future of their firms). This underscores that measures to strengthen and reward loyalty should be implemented with a view toward their impact on reinforcing loyalty over the longer term, ensuring continuity.

When employees adhere to a policy of delivering excellent service to each other, their satisfaction level also rises. This makes it easier for them to better serve external clients. Before looking at ways to manage and improve services, it is important to understand the nature of services and the problems posed by the goal of achieving “sustainable” excellence.

THE ELUSIVE NATURE OF SERVICES

A service by definition involves both a provider and a client. In delivering services, timing is often critical. Services cannot be stored or transported. They exist only for the period in which they are delivered. There is usually only one opportunity to get it right. There are no repairs or return policy. Services are produced and consumed. Services can be mass marketed. Yet without individual clients, one cannot deliver a service. When discussing a product, one usually refers to a tangible thing; something physical that can be touched, used, reused, stored, distributed, and traded. Unlike services, products can be mass produced and stored for distribution now or in future.

Now consider products as specifically bank “products.” These are mostly services. For example, when a bank offers a structured investment product, it is really selling a set of services, rights, and obligations; the services involve making the necessary transactions, accounting entries, compliance reviews, tracking performance, and ensuring that rights are upheld and obligations are met. Thus, when a bank “product” is sold, a monetary amount is deducted from the client’s account and payment notification is sent to a partner institution. Then, the rights to share in profit (or obligations to share in a loss) are recorded. At expiry, the bank contacts the partner in the transaction and receives the performance information, and the result is booked back to the client’s account. The only tangible thing exchanged in this process might be the investment prospectus and some printed statements. And unlike a true product, the investment is mostly a one-off event. There are usually deadlines, yields, and profits and/or losses that are linked to a single period in history. Even if the same “product” were to be offered a year later, the performance would almost certainly be different. This elusive and changeable aspect of services is important to keep in mind when, later in this chapter, ways to assess and improve this aspect of the business are discussed.

SUSTAINABLE EXCELLENCE

Apart from understanding the intangible nature of most services, it is also important to consider what clients expect in terms of services; this applies to both external and internal clients. Exceeding client expectations is the holy grail of service excellence. But this is not a realistic goal to be achieved on a lasting basis. Attempts to achieve service excellence will be affected by external factors that influence clients’ behaviour, as well as internal variables that affect employees’ performance. Continuous convenience and reliability are therefore the more practical goals to keep in mind during this discussion.

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, one common definition of service excellence is the ability to exceed client expectations. But this entails a number of potential pitfalls. It is hard enough just to meet expectations. Exceeding expectations is not a sustainable objective. Attempting to exceed expectations every time will inevitably lead to rising costs. Therefore, where does one draw the line to make it clear that by making an exception in certain cases or through offering a desirable incentive, one is not setting a precedent for the future? Also, exceeding expectations means going the extra mile. On the other hand, business processes run most efficiently when everyone sticks to predefined targets. Exceeding expectations is therefore useful only as a goal, if this can be done without incurring excessive costs and when other areas are not neglected as a result. Service excellence, therefore, must be about finding efficient, creative solutions rather than resorting to excess. Empirical studies have shown that most clients don’t actually expect a company to surprise them with new benefits continuously; instead, most want convenience and reliability. This is equally true inside the company; most people prefer accountable, reliable coworkers who are easy to get along with.

Clients’ wide range of expectations poses the main obstacle to achieving service excellence in private banking. One can never really exceed all the expectations that different clients might have. Not only are people different, but their needs constantly change. That doesn’t mean one cannot at least try to surpass expectations. This is precisely what private banking aspires to do by assigning a personal relationship manager to each client. This personalised service is what sets private banking apart from other financial sectors. In terms of internal service, here too, it is impossible to satisfy or exceed all employees’ expectation, which may vary considerably. It is therefore difficult to completely satisfy all clients or employees and completely bind them to an organisation. Some clients or employees also have a need for change and cannot be bound to any company. Nonetheless, a company can still aim to deliver service excellence to internal clients, meaning to its employees, in the form of reliability and convenience, a topic already touched on that will be looked at in more detail in the final section of this chapter, “Managing the Drivers of Service Excellence.”

The following section discusses what drives service excellence. It is followed by an overview that introduces some tools that can be used to objectively measure service quality and to improve it.

THE FOUR DRIVERS OF SERVICE EXCELLENCE

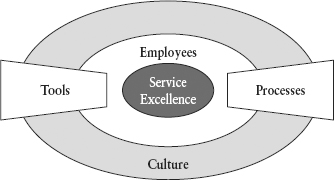

The four drivers of service excellence at any company are employees, culture, tools, and processes. Employees represent the single most important aspect, for it is they who provide the services. Based on this approach, Figure 9.2 offers a schematic representation of service excellence, showing that in all respects, employees are a category that is indispensable. Culture determines employees’ behaviour and attitudes toward the company. Other factors are relevant, including tools that take into account the locations, environments, and systems required by employees to deliver services. At the same time, business processes govern the methods and procedures used to do the work. But in the end, it all comes down to employees.

However, it is important to keep in mind that while it is impossible to deliver service excellence without going through the employees, employees also must work within the cultural framework established by the company, which includes tools and processes. Tools and processes can be thought of as avenues that take the company a step closer to service excellence, with employees necessary to bridge the final gap. Still, tools and processes extend beyond the boundaries of any single corporate culture. Different banks can rely on the same tools and processes, so it comes down to a particular culture and the individual employees at a particular bank to deliver service excellence. To make it clear in detail each of the separate elements—employees, culture, tools, and processes—are examined in detail in the following section.

Employees

Employees are the critical link in delivering service excellence. Employee behaviour needs to be guided to the extent that work has meaning and value. Companies must serve as anchors providing feedback to give employees a realistic assessment of where training is needed and could be of the greatest benefit. Companies also have to provide feedback on actual performance and the ideals they espouse. Key factors here include incentives both on a collective and individual level, and employee role management.

Employees are not only the biggest cost factor in private banking—they are also its primary asset. Without clients a bank is nothing, but without employees a bank is just a shell. Employees identify opportunities, create products, sign clients, manage assets, and distribute profits. Recruiting the best employees is hence the subject of Chapter 10, “Winning the War for Talent.” When they have the right prerequisites, they are already well on the way to engaging and winning clients, forging ties, and enhancing interactions, thereby encouraging loyalty to the institution and the brand.

Studies have identified four general categories determining whether employees are well-positioned to deliver service excellence: the working environment, leadership and organisation, workplace climate, trust, and personal affirmation.

Working Environment and Job Satisfaction

Studies show that the working environment has the single greatest influence on service excellence. Job satisfaction is included in this category, as is the employee’s belief as to whether the job he or she is doing is meaningful and enjoyable. Other factors that have an influence include the level of satisfaction within the entire department and employee turnover rates. But the fact that the job might be perceived as enjoyable or satisfying most likely depends on other factors, so in the end it makes little sense to establish programmes solely to make employees feel they matter within the organisation or to increase their level of satisfaction. It is better to address underlying concerns that determine job satisfaction. Being happy in a job is a natural outgrowth of working for a well-managed brand that engenders pride, coupled with strong authentic leadership that communicates to each employee his or her intrinsic worth.

Leadership and Organisation

Leadership and organisation include communication within an organisation, whether there is a “sense of justice” among staff, along with staff policies and the way the business is organised. Leadership in terms of service excellence starts at the top. It is expressed by the manner in which the CEO relates to the management team; this also means directly empowering employees through the ranks to make the right decisions based on sound judgement. The structures and framework of accountability must be put in place to allow employees to take the initiative and make the occasional exception to the rule. This enhances the entrepreneurial spirit within the company and fosters the creativity essential for finding new solutions to problems and more efficient ways to conduct business. The internal organisation needs to reflect the company’s strategy while being as lean as possible. If the company structure cannot be easily expressed graphically or verbally, the structure is probably too complex. Furthermore, a company should avoid the temptation to organise its structure around individuals. An organisation designed to cater to just a few people can give rise to a sense of favouritism among the rest of the employees.

Climate of Trust

A climate of trust and good personal chemistry is also vital. Friction among employees is sometimes inevitable. Management must address situations where conflicts might arise to ensure that different personalities enrich a team, rather than allowing problems to escalate. Genuine trust depends on a willingness to give people the benefit of the doubt and a second chance—forgiveness is an essential foundation for creating a positive climate and encouraging innovation.

Personal Affirmation

Personal affirmation means being valued as a person. This includes both financial and nonfinancial components. It also touches on internal transparency and dialogue both down and up the management chain. If management affirms an employee’s intrinsic value as a person by respecting his or her need for honest information, all employees will have greater reason to feel satisfied and motivated and ready to excel at what they do. Affirmation goes beyond saying simply “you’re doing a great job.” Authentic affirmation means getting feedback from each employee about his or her job, along with the pertinent obstacles and rewards it provides, so as to better understand the needs of each individual and then remedying or addressing problems to the greatest extent possible.

Key Personal Competencies That Determine Service Excellence

To raise the level of service excellence, it is important to know what attributes are desirable in new employees and what competencies need to be developed among existing employees through leadership, training, and organisation. In 1997, two German scholars, Heribert Gierl and Grit Helbich, published the results of an influential and widely cited empirical study based on a survey of 226 private banking clients. The purpose was to identify what sort of personal competencies clients found most desirable in a relationship manager (RM).(2) Based on the results, the following six traits were deemed highly important:

The traits sought by clients in RMs are also likely to be welcomed by employees in their coworkers. What is true for external clients is also true for “internal clients.” People prefer to work with colleagues who have the relevant information in their heads, are friendly, are concise, and are willing to go the extra mile in helping to solve a specific problem.

Culture

After employees, the second driver of service excellence is culture. Culture is the indefinable, intangible glue that holds together a group of people. It has a historical component arising from shared experiences and values. Within a company, it is related to patterns of behaviour any time employees interact. This type of corporate culture need not be spelled out in a rule book. To make successful use of culture to drive service excellence, it is important to promote the values and attitudes that give rise to the type of actions desired, rather than to narrowly define actions in terms of rules and processes. Culture must be lived from the top down and promoted by way of examples rather than through edicts.

Whenever two companies merge, there is a lot of discussion about integrating two different corporate cultures. But it is important to distinguish here between simply harmonising all the rules, systems, and processes and really merging the cultures. The rules and processes provide employees with guidelines on how to act or react in predefined situations. The culture provides a basis for employees to make decisions in cases that are not predefined and, where there can be no precise guidelines offered in advance, as to what the “correct” decision would be.

Following from that, the challenge in any organisation is how to communicate the knowledge staff needs to react in unforeseen or indefinable situations, in order to provide service excellence within the context of corporate culture. The key here is empowerment. Companies that lead their industry in terms of service excellence give their employees the leeway to make decisions within a framework that extends beyond the routine boundaries of what is included in the job description.

Culture also relates to the question of how one can best derive meaning from work and how a person relates to the job. Brand values need to be communicated not only to the clients but to employees, and employees have to identify with the brand and believe in it. Rewards and incentive programmes help make work meaningful and contribute as well to the corporate culture. Companies also need to find the right balance. If individual incentives are too powerful and focus too much on short-term results, this can backfire by encouraging selfish risk taking, which in the end will harm the company and undermine the brand. By the same token, collective incentives for an entire group may underscore the importance of teamwork. Used in isolation, however, such incentives could stifle individual initiative. Internal communication is needed to help employees understand the behaviour that is expected from them in relation to corporate values and culture. These ideals can be expressed through publications such as the employee magazine and through other internal communications. Most of all, they must be lived by senior management. In the end, senior managers must serve as vital role models. Their actions, behaviour, and attitudes ultimately will determine how a culture develops in any organisation.

Tools

Beyond employees and culture, tools also play a decisive role in delivering service excellence. Where service excellence is concerned, tools can include not only technology but resources, processes, and even budget allocations. It all depends on how these various resources are implemented. It is important to have the best tools possible, and having employees willing to use and adopt the tools at their disposal is critical to the process.

The ability to use tools allowed the human race to prosper and shape the world in which we live. By way of analogy, private banks need good tools related to their business in order to survive, grow, and expand into new markets.

When speaking of tools in private banking, what is often meant is a package of processes and resources. For example, tools for training and career development include a process for identifying a particular need of an individual employee and then mapping out that process to allocate resources best suited to the need. Most banks have development plans for staff that include structured discussions. In these periodic interviews with employees, an employee’s immediate supervisor discusses progress in attaining goals such as target competencies as well as the employee’s desired path of career development. Interim steps necessary to meet these targets are discussed, and measures might be agreed on to improve knowledge and skills or performance.

Finally, technology-based tools give clients better access to relationship managers, making it easier for clients to reach their RM via email or mobile devices around the clock. RMs’ availability is one of the single most important criteria clients use to judge a private bank. When introducing new technology-based tools it is also important to ensure that sufficient training is provided to the RMs to provide for effective use. When determining the scope of such training, it is therefore critical to consider RMs’ experience with similar technologies and adaptability.

Processes

Processes are the fourth and final key service driver in this discussion. Services are processes. These processes can be predefined, or they can arise spontaneously. Private banking differs from retail banking in that it offers clients a bespoke service. How far can it go in defining “fixed processes” (procedures that are predefined, and add value and efficiency)? The main thing is to be clear about the processes used and to be in position to tap individual employees’ creativity and insights to improve individual processes.

No matter how idealistic a company is about encouraging employees to take the initiative, a bank cannot exist without some predefined and predetermined processes.* Based on service excellence surveys, the most common complaint among employees is that they were often not sure precisely which process should be used for a particular function. The employees often did not know whom they should ask when it came questions about a process. This is certain to be the case in many organisations. To build a culture of excellence it is important to address these problems through training, and by informing and connecting people, as well as by organising knowledge within the organisation so people can find it quickly when they need it.

Processes are a particular challenge for private banks because they offer clients customised services and products. This means that the efforts to standardise processes and train employees in how to apply the processes always lag behind the development of new solutions for clients, tending to adapt and be flexible as needs arise. Processes, too, must give employees sufficient freedom to act based on judgement and common sense, as long as they don’t contravene or compromise the company’s values and traditions, as defined and understood within its particular cultural framework.

Apart from ensuring individual attention, processes must be efficient. Designing an efficient process is increasingly difficult as the world grows ever more complex. The market is constantly changing, products are becoming more sophisticated, and regulatory and institutional requirements are in constant flux. Just as the frontline staff often have the best instincts with regard to what customers need, back-office staff frequently have ideas about how to improve a process. Therefore, a bank needs to listen to its employees and offer rewards and incentives for ideas that help to increase process efficiency.

MEASURING SERVICE EXCELLENCE

Private banks create value through services, which by their very nature are hard to assess. The most common approaches to measuring service quality rely on employee and client surveys. By measuring responses of employees and clients and comparing them to ideals or minimum standards that serve as references, it is possible to introduce measures for improvement. Progress also can be assessed by repeating surveys.

If the goal is to build a culture of excellence, the people the bank hires must have a healthy sense of intuition about how things should be and then should be empowered to initiate changes, drawing on their instinct and experience. Not only is every organisation unique; so, too is past experience sometimes insufficient as a guide when it comes to initiating change. Often, issues might also affect large numbers of employees or customers across the entire organisation, who all might be affected by certain changes and deserve a voice. Surveys are therefore both essential and powerful tools that can be applied when the goal is to uncover answers to issues difficult to capture in other ways, including through quantitative assessments. Surveys also provide “semi-tangible” evidence of areas that need attention. Furthermore, they can be used to offer insight on the progress of measures already introduced.

The Gaps Model: An Introduction to SERVQUAL Gaps

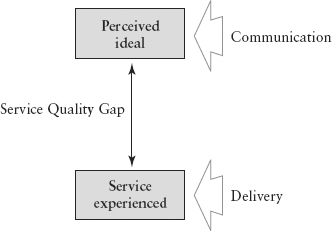

It is impossible to spend time discussing how to measure service quality without encountering the SERVQUAL gap method, which is widely used across a range of different fields. Thanks to its practicality, SERVQUAL has been employed by businesses ranging from real estate brokerage to medical services, utilities, and education, to name just a few. The concept was developed by Valarie A. Zeithaml, A. Parasuraman, and Leonard L. Berry,(3) whose work forms the basis for much of what has been written subsequently. They base their approach on two key premises. The first is that respondents’ ranking of service quality experiences or perceptions is consistent, allowing service quality to be measured through surveys. The second is that service quality excellence can be measured against an “ideal”; respondents’ perceptions of how close actual service comes to that ideal produce a score or ranking (“gap”). This approach eliminates the need for an objective measure of quality. Such surveys also can be used to track how respondents’ expectations evolve over time.

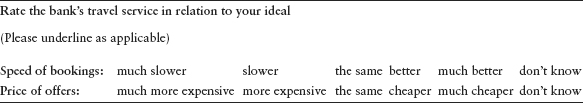

A SERVQUAL survey consists of a series of questions asking respondents to rate the service they received in terms of how it compares with their desired level of service. Figure 9.3 shows the service quality gap; the “perceived ideal” at the top of the illustration exists in the minds of the survey’s respondents and is influenced by communication (for the internal client, or employee, this would encompass all forms of internal communication), along with past experiences and clients’ needs. The “service experienced” on the lower level describes how the respondent views actual delivery of the service. Examples of the questions that can be used to assess the gap between real and ideal are shown in Figure 9.4, based on a survey about a company’s efforts to improve its in-house travel offering to employees.

Everything that follows in terms of discussions about SERVQUAL and the “gaps” it reveals is basically an extension of the ideas just outlined. The concept is attractive because it standardises the dimensions of the service quality and the types of gaps that can be measured. Refinements also can be introduced. For example, respondents might be asked to compare a service not only with a perceived ideal but with a minimum acceptable level. This is called a two-pole survey. The two-pole method allows actual and ideal levels to be measured, and it also can be used to determine the zone of tolerance in each case so that priorities can be more accurately assessed and assigned.

SERVQUAL Dimensions

In an attempt to make service quality comparable in different contexts, it is also possible to define the key areas or “dimensions” of service quality. While the early treatment of SERVQUAL incorporated 22 measures, the method was later streamlined to just five: Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy. These can be ordered to spell out the “RATER” list. Questions are then designed to gather information about these five key aspects:(4)

Types of Gaps

Consider once again the internal clients—employees. Table 9.1 provides a general overview of a real-life situation that might arise in a business, illustrating the types of gaps(5) that exist between actual and ideal, using the perceptions of employees on the one hand and management on the other.

TABLE 9.1 Types of Gaps: Where Might the Actual Experience Fall Short?

Source: Author

| Staff Perception | Type of Gap | Management Perception |

| “Something needs to be improved” | Knowledge Gap | “Everything is going according to plan” |

| “Process should do X” | Design Gap | “Process does Y” |

| “Process works but too slowly” | Performance Gap | “Process solves the real problem” |

| “Process saves the company money” | Communications Gap | “Process will save you time” |

By way of a concrete illustration of how this works, the following example shows how a company sought to improve the way it provides travel arrangements to employees.

Gap 1: The Knowledge Gap: The Knowledge of What the Client (Employee) Wants Is Missing

In the past, a bank booked all flights for relationship managers (RMs) through a travel agency. With the move to profit centre accounting for RMs, the bank decided to allow them to book their own flights. The assumption was that RMs, because they are accountable for the costs, would prefer the flexibility, speed, and cost control associated with making their own bookings. The bank provided a list of recommended online sites and travel agencies. Soon after the switch, feedback began to come in, and it became apparent that there was a “Gap 1.” Management’s perception of what employees wanted differed from the employees’ actual expectations. Employees wanted more support and a less time-consuming arrangement.

Gap 2: The Design Gap: The Right Service Design and Standards Are Not in Place

In response to the information gleaned from gap 1, the bank set up an internal travel service to save RMs time by handling the online booking or arrangements with travel agents. The service was implemented. RMs were then able to contact the internal travel agent themselves, and this office, once briefed, assembled a list of options to choose from. Unfortunately, this system was under-staffed and unable to cope with surges in demand. RMs found that the flights chosen could no longer be confirmed at an agreed price, and so forth. This is an example of “Gap 2,” meaning a mismatch between what management envisaged and how the service worked in practice.

Gap 3: The Service Performance Gap: There Is a Failure to Deliver Value

In response to this discovery, the bank introduced a standardised, internal Web-based booking platform. It was efficient and quick. But the actual take-up was low. RMs complained that the prices were a lot higher than they could obtain by doing the booking themselves directly online. This illustrates a “Gap 3” between desired and delivered service performance.

Gap 4: The Communications Gap: Management Is Mistaken in Its Assessments

Management then realised that to obtain the economies of scale they would have to ensure that all company business travel was booked through the platform. To achieve this, they informed employees that in the future all travel arrangements had to be booked through the company platform. External arrangements would have to be paid privately. Management communicated this to employees, saying that the measure was justified by the fact that it would allow savings of 20 percent compared with individual bookings. At the end of the year RMs complained that the actual savings were effectively only 10 percent. This illustrates “Gap 4,” the difference between the goal as communicated and the result.

This process did in fact lead in the end to adoption of a satisfactory reservation system, one that met the needs of employees and was in line with the parameters established by management. However, this bank went through a number of iterations before achieving a solution that represents a compromise between an ideal and what was possible in reality. This demonstrates that SERVQUAL is by nature a responsive and flexible tool that can be applied in a series of steps to make changes. SERVQUAL’s power can best be achieved when the procedure is applied to very specific areas affecting people, processes, and tools within an organisation.

Using SERVQUAL in Private Banking: Practical Steps in Creating a Service Excellence Culture

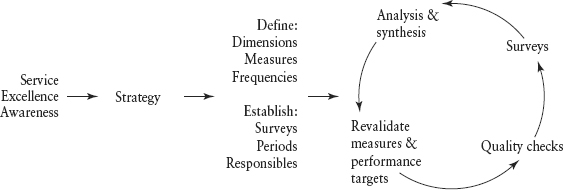

To achieve service excellence, a private bank must establish how it coordinates and manages the process. Depending on the size of the organisation, this might require one or more people dedicated to the task. The project could comprise six steps that form a closed loop—for example:

Conducting a Survey

The initial survey should establish the point of departure. To make an effective assessment, the survey should meet a number of criteria regarding both the employees’ involvement and the topics that the survey questions will address:

Analysing Results

When analysing the results, look at both specific information and general trends and tendencies. Insights can be gained by comparing the overall results in different departments. They can also be compared on the basis of different topics or “dimensions” such as those outlined in the “RATER” system. Once the second “turn” of the cycle is entered, it could be interesting to compare results of the earlier survey with the later one to see if the measures yielded the desired improvements. There is no limit to the ways the data can be dissected and how different aspects can be compared to offer a wealth of information, providing the survey is done on a large scale. For example: human resources could respond to a survey on tools used by that department, which could be compared to responses to the same survey regarding these tools, whereas other managers and employees are asked about the tools available and so on. This might reveal that although there are in fact adequate development tools, internal communication about these is lacking; as a result there is a perceived deficit of such tools among employees. Alternatively, it may mean that management needs to confront the fact that such tools are really missing and make the vital investments in career development.

Defining General Objectives

Based on the ratings obtained through such surveys, general objectives can be defined for each department. The results of other departments can serve as benchmarks in terms of what level of rating can or should be expected. When determining the new objectives, it is wise to use caution in finding the right balance between a realistic challenge and the risk of setting unrealistic goals that will lead only to discouragement. Seeing goals realised based on the outcome of regular surveys should serve to motivate employees to make further improvements.

Defining Specific Measures

The measures addressed by the survey should fulfil the so-called SMART objectives: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. For example, the human resources department needs to liaise with other departments on a regular basis to establish what is required of job candidates who are interviewed. There needs to be a formal process covering the shared creation of the job description, agreement on place of recruitment, screening of potential candidates’ curricula vitae, and so forth.

Implementing Measures

When implementing the various measures to address points already identified and defined, prioritising is critical because resources need to be focused on those measures that have the greatest impact. A matrix approach can help identify these priorities. Position each measure along the X-axis according to its degree of importance to the client and situate it relative to the Y-axis according to a measure’s efficiency, feasibility, and cost. The expected impact that such a measure is having, based on results of follow-up surveys, can help quantify how much efficiency it has provided. It might also be a good idea to consider the time needed to implement the measures and perhaps to attach a weighting to the various criteria so as to fine-tune the system.

Instituting Quality Checks

The final step is to implement the measures and provide employees with a status update. These steps can be carried out with the use of regular spot checks. In this fashion, it also is possible to gauge the improvement that is still needed to meet the target, in terms of whatever rating level was selected as an achievable goal. These spot checks can be carried out before the next regular survey is conducted. Quality checks also ensure that improvements become part of the bank’s culture, rather than a short-lived phenomenon based on good intentions. To this end, one can introduce a tracking and reporting process involving collecting information centrally, checking whether results are valid, monthly reporting, quality checks, and a quarterly departmental review to gain feedback, and so on.

CONCLUSION

Service excellence means coordinating all elements of the internal organisation to work in harmony, allowing employees to gain efficiency and perform to the highest possible standards. Service excellence is sustainable only when it is treated as a series of incremental improvements applied to every area of the organisation, where changes and modifications are part of the process to achieve the stated objective. The idea of exceeding expectations to attain an unrealistic goal should be abandoned in favour of consistency and reliability. There should be great emphasis on ensuring a culture of trust and affirmation from the top down. In this way, leadership and the organisation can create the right working environment, which is the number-one priority when creating the necessary climate for employees to achieve the goal of service excellence.

NOTES

1. Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E., and Schlesinger, L.A. 1994. “Putting the Service-Profit Chain to Work.” Harvard Business Review 72(2): 164–170.

2. Gierl, H. and Helbich, G. 1997. Die Kompetenz des Bankberaters, in Die Bank, 37. Jg., Nr. 9.

3. Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L,L., and Parasuraman, A. 1985. “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research.” Journal of Marketing vol. 49.

4. Hernon, P. and Altman, E. 1996. Service Quality in Academic Libraries. Ablex Publishing Corp.

5. See note 3 above.

*Client experience is presented in detail in Chapter 8, “Delivering A Superior Client Experience.”

*There are numerous processes used in private banking, far too many to mention in detail in the space provided here. A few typical examples include processes for opening an account, the investment process, the advisory process, the security transaction process, and so on.