The Variables for Success

9.0 INTRODUCTION

Project management cannot succeed unless the project manager is willing to employ the systems approach to project management by analyzing those variables that lead to success and failure. This chapter briefly discusses the dos and don'ts of project management and provides a “skeleton” checklist of the key success variables. The following four topics are included:

- Predicting project success

- Project management effectiveness

- Expectations

9.1 PREDICTING PROJECT SUCCESS

One of the most difficult tasks is predicting whether the project will be successful. Most goal-oriented managers look only at the time, cost, and performance parameters. If an out-of-tolerance condition exists, then additional analysis is required to identify the cause of the problem. Looking only at time, cost, and performance might identify immediate contributions to profits, but will not identify whether the project itself was managed correctly. This takes on paramount importance if the survival of the organization is based on a steady stream of successfully managed projects. Once or twice a program manager might be able to force a project to success by continually swinging a large baseball bat. After a while, however, either the effect of the big bat will become tolerable, or people will avoid working on his projects.

Project success is often measured by the “actions” of three groups: the project manager and team, the parent organization, and the customer's organization. There are certain actions that the project manager and team can take in order to stimulate project success. These actions include:

- Insist on the right to select key project team members.

- Select key team members with proven track records in their fields.

- Develop commitment and a sense of mission from the outset.

- Seek sufficient authority and a projectized organizational form.

- Coordinate and maintain a good relationship with the client, parent, and team.

- Seek to enhance the public's image of the project.

- Have key team members assist in decision-making and problem-solving.

- Develop realistic cost, schedule, and performance estimates and goals.

- Have backup strategies in anticipation of potential problems.

- Provide a team structure that is appropriate, yet flexible and flat.

- Go beyond formal authority to maximize influence over people and key decisions.

- Employ a workable set of project planning and control tools.

- Avoid overreliance on one type of control tool.

- Stress the importance of meeting cost, schedule, and performance goals.

- Give priority to achieving the mission or function of the end-item.

- Keep changes under control.

- Seek to find ways of assuring job security for effective project team members.

In Chapter 4 we stated that a project cannot be successful unless it is recognized asa project and has the support of top-level management. Top-level management must be willing to commit company resources and provide the necessary administrative support so that the project easily adapts to the company's day-to-day routine of doing business. Furthermore, the parent organization must develop an atmosphere conducive to good working relationships between the project manager, parent organization, and client organization.

With regard to the parent organization, there exist a number of variables that can be used to evaluate parent organization support. These variables include:

- A willingness to coordinate efforts

- A willingness to maintain structural flexibility

- A willingness to adapt to change

- Effective strategic planning

- Rapport maintenance

- Proper emphasis on past experience

- External buffering

- Prompt and accurate communications

- Enthusiastic support

- Identification to all concerned parties that the project does, in fact, contribute to parent capabilities

The mere identification and existence of these variables do not guarantee project success in dealing with the parent organization. Instead, they imply that there exists a good foundation with which to work so that if the project manager and team, and the parent organization, take the appropriate actions, project success is likely. The following actions must be taken:

- Select at an early point, a project manager with a proven track record of technical skills, human skills, and administrative skills (not necessarily in that order) to lead the project team.

- Develop clear and workable guidelines for the project manager.

- Delegate sufficient authority to the project manager, and let him make important decisions in conjunction with key team members.

- Demonstrate enthusiasm for and commitment to the project and team.

- Develop and maintain short and informal lines of communication.

- Avoid excessive pressure on the project manager to win contracts.

- Avoid arbitrarily slashing or ballooning the project team's cost estimate.

- Avoid “buy-ins.”

- Develop close, not meddling, working relationships with the principal client contact and project manager.

Both the parent organization and the project team must employ proper managerial techniques to ensure that judicious and adequate, but not excessive, use of planning, controlling, and communications systems can be made. These proper management techniques must also include preconditioning, such as:

- Clearly established specifications and designs

- Realistic schedules

- Realistic cost estimates

- Avoidance of “buy-ins”

- Avoidance of overoptimism

The client organization can have a great deal of influence on project success by minimizing team meetings, making rapid responses to requests for information, and simply letting the contractor “do his thing” without any interference. The variables that exist for the client organization include:

- A willingness to coordinate efforts

- Rapport maintenance

- Establishment of reasonable and specific goals and criteria

- Well-established procedures for changes

- Prompt and accurate communications

- Commitment of client resources

- Minimization of red tape

- Providing sufficient authority to the client contact (especially for decision-making)

With these variables as the basic foundation, it should be possible to:

- Encourage openness and honesty from the start from all participants

- Create an atmosphere that encourages healthy competition, but not cutthroat situations or “liars'” contests

- Plan for adequate funding to complete the entire project

- Develop clear understandings of the relative importance of cost, schedule, and technical performance goals

- Develop short and informal lines of communication and a flat organizational structure

- Delegate sufficient authority to the principal client contact, and allow prompt approval or rejection of important project decisions

- Reject “buy-ins”

- Make prompt decisions regarding contract award or go-ahead

- Develop close, not meddling, working relationships with project participants

- Avoid arms-length relationships

- Avoid excessive reporting schemes

- Make prompt decisions regarding changes

By combining the relevant actions of the project team, parent organization, and client organization, we can identify the fundamental lessons for management. These include:

- When starting off in project management, plan to go all the way.

- Recognize authority conflicts—resolve.

- Recognize change impact—be a change agent.

- Match the right people with the right jobs.

- No system is better than the people who implement it.

- Allow adequate time and effort for laying out the project groundwork and defining work:

- Work breakdown structure

- Network planning

- Ensure that work packages are the proper size:

- Manageable, with organizational accountability

- Realistic in terms of effort and time

- Establish and use planning and control systems as the focal point of project implementation:

- Know where you're going.

- Know when you've gotten there.

- Be sure information flow is realistic:

- Information is the basis for problem-solving and decision-making.

- Communication “pitfalls” are the greatest contributor to project difficulties.

- Be willing to replan—do so:

- The best-laid plans can often go astray.

- Change is inevitable.

- Tie together responsibility, performance, and rewards:

- Management by objectives

- Key to motivation and productivity

- Long before the project ends, plan for its end:

- Disposition of personnel

- Disposal of material and other resources

- Transfer of knowledge

- Closing out work orders

- Customer/contractor financial payments and reporting

The last lesson, project termination, has been the downfall for many good project managers. As projects near completion, there is a natural tendency to minimize costs by transferring people as soon as possible and by closing out work orders. This often leaves the project manager with the responsibility for writing the final report and transferring raw materials to other programs. Many projects require one or two months after work completion simply for administrative reporting and final cost summary.

Having defined project success, we can now identify some of the major causes for the failure of project management:

- Selection of a concept that is not applicable. Since each application is unique, selecting a project that does not have a sound basis, or forcing a change when the time is not appropriate, can lead to immediate failure.

- Selection of the wrong person as project manager. The individual selected must be more of a manager than a doer. He must place emphasis on all aspects of the work, not merely the technical.

- Upper management that is not supportive. Upper management must concur in the concept and must behave accordingly.

- Inadequately defined tasks. There must exist an adequate system for planning and control such that a proper balance between cost, schedule, and technical performance can be maintained.

- Misused management techniques. There exists the inevitable tendency in technical communities to attempt to do more than is initially required by contract. Technology must be watched, and individuals must buy only what is needed.

- Project termination that is not planned. By definition, each project must stop. Termination must be planned so that the impact can be identified.

9.2 PROJECT MANAGEMENT EFFECTIVENESS1

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Chapter 4 Intergration Management

Chapter 9 Human Resources Management

Chapter 10 Communications Management

Project managers interact continually with upper-level management, perhaps more so than with functional managers. Not only the success of the project, but even the career path of the project manager can depend on the working relationships and expectations established with upper-level management. There are four key variables in measuring the effectiveness of dealing with upper-level management. These variables are credibility, priority, accessibility, and visibility:

- Credibility

- Credibility comes from being a sound decision maker.

- It is normally based on experience in a variety of assignments.

- It is refueled by the manager and the status of his project.

- Making success visible to others increases credibility.

- To be believable, emphasize facts rather than opinions.

- Give credit to others; they may return this favor.

- Priority

- Sell the specific importance of the project to the objectives of the total organization.

- Stress the competitive aspect, if relevant.

- Stress changes for success.

- Secure testimonial support from others—functional departments, other managers, customers, independent sources.

- Emphasize “spin-offs” that may result from projects.

- Anticipate “priority problems.”

- Sell priority on a one-to-one basis.

- Accessibility

- Accessibility involves the ability to communicate directly with top management.

- Show that your proposals are good for the total organization, not just the project.

- Weigh the facts carefully; explain the pros and cons.

- Be logical and polished in your presentations.

- Become personally known by members of top management.

- Create a desire in the “customer” for your abilities and your project.

- Make curiosity work for you.

- Visibility

- Be aware of the amount of visibility you really need.

- Make a good impact when presenting the project to top management.

- Adopt a contrasting style of management when feasible and possible.

- Use team members to help regulate the visibility you need.

- Conduct timely “informational” meetings with those who count.

- Use available publicity media.

9.3 EXPECTATIONS

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Chapter 9 Human Resources Management

Chapter 10 Commnunications Management

In the project management environment, the project managers, team members, and upper-level managers each have expectations of what their relationships should be with the other parties. To illustrate this, top management expects project managers to:

- Assume total accountability for the success or failure to provide results

- Provide effective reports and information

- Provide minimum organizational disruption during the execution of a project

- Present recommendations, not just alternatives

- Have the capacity to handle most interpersonal problems

- Demonstrate a self-starting capacity

- Demonstrate growth with each assignment

At first glance, it may appear that these qualities are expected of all managers, not necessarily project managers. But this is not true. The first four items are different. The line managers are not accountable for total project success, just for that portion performed by their line organization. Line managers can be promoted on their technical ability, not necessarily on their ability to write effective reports. Line managers cannot disrupt an entire organization, but the project manager can. Line managers do not necessarily have to make decisions, just provide alternatives and recommendations.

Just as top management has expectations of project managers, project managers have certain expectations of top management. Project management expects top management to:

- Provide clearly defined decision channels

- Take actions on requests

- Facilitate interfacing with support departments

- Assist in conflict resolution

- Provide sufficient resources/charter

- Provide sufficient strategic/long-range information

- Provide feedback

- Give advice and stage-setting support

- Define expectations clearly

- Provide protection from political infighting

- Provide the opportunity for personal and professional growth

The project team also has expectations of their leader, the project manager. The project team expects the project manager to:

- Assist in the problem-solving process by coming up with ideas

- Provide proper direction and leadership

- Provide a relaxed environment

- Interact informally with team members

- Stimulate the group process

- Facilitate adoption of new members

- Reduce conflicts

- Defend the team against outside pressure

- Resist changes

- Act as the group spokesperson

- Provide representation with higher management

In order to provide high task efficiency and productivity, a project team should have certain traits and characteristics. A project manager expects the project team to:

- Demonstrate membership self-development

- Demonstrate the potential for innovative and creative behavior

- Communicate effectively

- Be committed to the project

- Demonstrate the capacity for conflict resolution

- Be results oriented

- Be change oriented

- Interface effectively and with high morale

Team members want, in general, to fill certain primary needs. The project manager should understand these needs before demanding that the team live up to his expectations. Members of the project team need:

- A sense of belonging

- Interest in the work itself

- Respect for the work being done

- Protection from political infighting

- Job security and job continuity

- Potential for career growth

Project managers must remember that team members may not always be able to verbalize these needs, but they exist nevertheless.

9.4 LESSONS LEARNED

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Professional Responsibility Task #2—Contribute to the PM Knowledge Base

Lessons can be learned from each and every project, even if the project is a failure. But many companies do not document lessons learned because employees are reluctant to sign their names to documents that indicate they made mistakes. Thus employees end up repeating the mistakes that others have made.

Today, there is increasing emphasis on documenting lessons learned. Boeing maintains diaries of lessons learned on each airplane project. Another company conducts a postimplementation meeting where the team is required to prepare a three- to five-page case study documenting the successes and failures on the project. The case studies are then used by the training department in preparing individuals to become future project managers. Some companies even mandate that project managers keep project notebooks documenting all decisions as well as a project file with all project correspondence. On large projects, this may be impractical.

Most companies seem to prefer postimplementation meetings and case study documentation. The problem is when to hold the postimplementation meeting. One company uses project management for new product development and production. When the first production run is complete, the company holds a postimplementation meeting to discuss what was learned. Approximately six months later, the company conducts a second postimplementation meeting to discuss customer reaction to the product. There have been situations where the reaction of the customer indicated that what the company thought they did right turned out to be a wrong decision. A follow-up case study is now prepared during the second meeting.

9.5 UNDERSTANDING BEST PRACTICES

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Professional Responsibility Task #2—Contribute to the PM Knowledge Base

One of the benefits of understanding the variable of success is that it provides you with a means for capturing and retaining best practices. Unfortunately this is easier said than done. There are multiple definitions of a best practice, such as:

- Something that works

- Something that works well

- Something that works well on a repetitive basis

- Something that leads to a competitive advantage

- Something that can be identified in a proposal to generate business

In the author's opinion, best practices are those actions or activities undertaken by the company or individuals that lead to a sustained competitive advantage in project management.

It has only been in recent years that the importance of best practices has been recognized. In the early years of project management, there were misconceptions concerning project management. Some of the misconceptions included:

- Project management is a scheduling tool such as PERT/CPM scheduling.

- Project management applies to large projects only.

- Project management is designed for government projects only.

- Project managers must be engineers and preferably with advanced degrees.

- Project managers need a “command of technology” to be successful.

- Project success is measured in technical terms only.

As project management evolved, best practices became important. Best practices can be learned from both successes and failures. In the early years of project management, private industry focused on learning best practices from successes. The government, however, focused on learning about best practices from failures. When the government finally focused on learning from successes, the knowledge on best practices came from their relationships with both their prime contractors and the subcontractors. Some of the best practices that came out of the government included:

- Use of life-cycle phases

- Standardization and consistency

- Use of templates for planning, scheduling, control, and risk

- Providing military personnel in project management positions with extended tours of duty at the same location

- Use of integrated project teams (IPTs)

- Control of contractor-generated scope changes

- Use of earned-value measurement (discussed in Chapter 15)

What to Do with a Best Practice?

With the definition that a best practice leads to a sustained competitive advantage, it is no wonder that some companies were reluctant to make their best practices known to the general public. Therefore, what should a company do with its best practices if not publicize them? The most common options available include:

- Sharing Knowledge Internally Only: This is accomplished using the company intranet to share information with employees. There may be a separate group within the company responsible for control of the information, perhaps even the project management officer (PMO).

- Hidden from All But a Selected Few: Some companies spend vast amounts of money on the preparation of forms, guidelines, templates, and checklists for project management. These documents are viewed as both company-proprietary information and best practices and are provided to only a select few on a need-to-know basis. An example of a “restricted” best practice might be specialized forms and templates for project approval wherein information contained within may be company-sensitive financial data or the company's position on profitability and market share.

- Advertise to Your Customers: In this approach, companies may develop a best practices brochure to market their achievements and may also maintain an extensive best practices library that is shared with their customers after contract award.

Even though companies collect best practices, not all best practices are shared outside of the company, even during benchmarking studies where all parties are expected to share information. Students often ask why textbooks do not include more information on detailed best practices such as forms and templates. One company commented to the author:

We must have spent at least $1 million over the last several years developing an extensive template on how to evaluate the risks associated with transitioning a project from engineering to manufacturing. Our company would not be happy giving this template to everyone who wants to purchase a book for $80. Some best practices templates are common knowledge and we would certainly share this information. But we view the transitioning template as proprietary knowledge not to be shared.

Critical Questions

There are several questions that must be addressed before an activity is recognized as a best practice. Three frequently asked questions are:

- Who determines that an activity is a best practice?

- How do you properly evaluate what you think is best practice to validate that in fact it is a true best practice?

- How do you get executives to recognize that best practices are true value-added activities and should be championed by executive management?

Some organizations have committees that have as their primary function the evaluation of potential best practices. Other organizations use the PMO to perform this work. These committees most often report to senior levels of management.

There is a difference between lessons learned and best practices. Lessons learned can be favorable or unfavorable, whereas best practices are usually favorable outcomes.

Evaluating whether or not something is a best practice is not time-consuming, but it is complex. Simply believing that an action is a best practice does not mean that it is a best practice. PMOs are currently developing templates and criteria for determining whether an activity may qualify as a best practice. Some items that may be included in the template are:

- Is it a measurable metric?

- Does it identify measurable efficiency?

- Does it identify measurable effectiveness?

- Does it add value to the company?

- Does it add value to the customers?

- Is it transferable to other projects?

- Does it have the potential for longevity?

- Is it applicable to multiple users?

- Does it differentiate us from our competitors?

- Will the best practice require governance?

- Will the best practice require employee training?

- Is the best practice company proprietary knowledge?

One company had two unique characteristics in its best practices template:

- Helps to avoid failure

- In a crisis, helps to resolve a critical situation

Executives must realize that these best practices are, in fact, intellectual property to benefit the entire organization. If the best practice can be quantified, then it is usually easier to convince senior management.

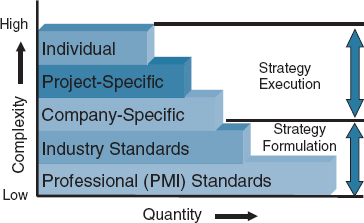

FIGURE 9-1. Levels of best practices.

Levels of Best Practices

Best practices can be discovered anywhere within or outside an organization. Figure 9-1 shows various levels of best practices. The bottom level is the professional standards level, which would include professional standards as defined by PMI®. The professional standards level contains the greatest number of best practices, but they are general rather than specific and have a low level of complexity.

The industry standards level identifies best practices related to performance within the industry. For example, the automotive industry has established standards and best practices specific to the auto industry.

As we progress to the individual best practices in Figure 9-1, the complexity of the best practices goes from general to very specific applications and, as expected, the quantity of best practices is less. An example of a best practice at each level might be (from general to specific):

- Professional Standards: Preparation and use of a risk management plan, including templates, guidelines, forms, and checklists for risk management.

- Industry-Specific: The risk management plan includes industry best practices such as the best way to transition from engineering to manufacturing.

- Company-Specific: The risk management plan identifies the roles and interactions of engineering, manufacturing, and quality assurance groups during transition.

- Project-Specific: The risk management plan identifies the roles and interactions of affected groups as they relate to a specific product/service for a customer.

- Individual: The risk management plan identifies the roles and interactions of affected groups based upon their personal tolerance for risk, possibly through the use of a responsibility assignment matrix prepared by the project manager.

Best practices can be extremely useful during strategic planning activities. As shown in Figure 9-2, the bottom two levels may be more useful for project strategy formulation whereas the top three levels are more appropriate for the execution of a strategy.

FIGURE 9-2. Usefulness of best practices.

Common Beliefs

There are several common beliefs concerning best practices. A partial list includes:

- Because best practices can be interrelated, the identification of one best practice can lead to the discovery of another best practice, especially in the same category or level of best practices.

- Because of the dependencies that can exist between best practices, it is often easier to identify categories of best practices rather than individual best practices.

- Best practices may not be transferable. What works well for one company may not work for another company.

- Even though some best practices seem simplistic and common sense in most companies, the constant reminder and use of these best practices lead to excellence and customer satisfaction.

- Best practices are not limited exclusively to companies in good financial health

Care must be taken that the implementation of a best practice does not lead to detrimental results. One company decided that the organization must recognize project management as a profession in order to maximize performance and retain qualified people. A project management career path was created and integrated into the corporate reward system.

Unfortunately the company made a severe mistake. Project managers were given significantly larger salary increases than line managers and workers. People became jealous of the project managers and applied for transfer into project management thinking that the “grass was greener.” The company's technical prowess diminished and some people resigned when not given the opportunity to become project managers.

Companies can have the greatest intentions when implementing best practices and yet detrimental results can occur. Table 9-1 identifies some possible expectations and the detrimental results that can occur. The poor results could have been the result of poor expectations or not fully understanding the possible ramifications after implementation.

There are other reasons why best practices can fail or provide unsatisfactory results. These include:

- Lack of stability, clarity, or understanding of the best practice

- Failure to use best practices correctly

- Identifying a best practice that lacks rigor

- Identifying a best practice based upon erroneous judgment

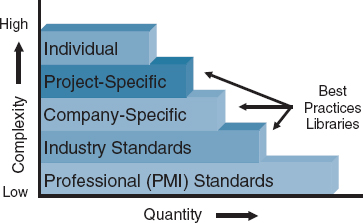

Best Practices Library

With the premise that project management knowledge and best practices are intellectual property, how does a company retain this information? The solution is usually the creation of a best practices library. Figure 9-3 shows the three levels of best practices that seem most appropriate for storage in a best practices library.

Figure 9-4 shows the process of creating a best practices library. The bottom level is the discovery and understanding of what is or is not a “potential” best practice. The sources for potential best practices can originate anywhere within the organization.

The next level is the evaluation level to confirm that it is a best practice. The evaluation process can be done by the PMO or a committee but should have involvement by the senior levels of management. The evaluation process is very difficult because a one-time positive occurrence may not reflect a best practice. There must exist established criteria for the evaluation of a best practice.

Once it is agreed upon that a best practice exists, it must be classified and stored in some retrieval system such as a company intranet best practices library.

Figure 9-1 shows the levels of best practices, but the classification system for storage purposes can be significantly different. Figure 9-5 shows a typical classification system for a best practices library.

TABLE 9-1. RESULTS OF IMPLEMENTING BEST PRACTICES

FIGURE 9-3. Levels of best practices.

FIGURE 9-4. Creating a best practices library.

The purpose for creating a best practices library is to transfer knowledge to employees. The knowledge can be transferred through the company intranet, seminars on best practices, and case studies. Some companies require that the project team prepare case studies on lessons learned and best practices before the team is disbanded. These companies then use the case studies in company-sponsored seminars. Best practices and lessons learned must be communicated to the entire organization. The problem is determining how to do it effectively.

Another critical problem is best practices overload. One company started up a best practices library and, after a few years, had amassed hundreds of what were considered to be best practices. Nobody bothered to reevaluate whether or not all of these were still best practices. After reevaluation had taken place, it was determined that less than one-third of these were still regarded as best practices. Some were no longer best practices, others needed to be updated, and others had to be replaced with newer best practices.

FIGURE 9-5. Best practices library.

9.6 STUDYING TIPS FOR THE PMI® PROJECT MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION EXAM

This section is applicable as a review of the principles to support the knowledge areas and domain groups in the PMBOK® Guide. This chapter addresses:

- Communications Management

- Initiation

- Planning

- Execution

- Monitoring

- Closure

Understanding the following principles is beneficial if the reader is using this text to study for the PMP® Certification Exam:

- Importance of capturing and reporting best practices as part of all project management processes

- Variables for success

The following multiple-choice questions will be helpful in reviewing the principles of this chapter:

- Lessons learned and best practices are captured:

- Only at the end of the project

- Only after execution is completed

- Only when directed to do so by the project sponsor

- At all times but primarily at the closure of each life-cycle phase

- The person responsible for the identification of a best practice is the:

- Project manager

- Project sponsor

- Team member

- All of the above

- The primary benefit of capturing lessons learned is to:

- Appease the customer

- Appease the sponsor

- Benefit the entire company on a continuous basis

- Follow the PMBOK® requirements for reporting

ANSWERS

- D

- D

- C

PROBLEMS

9–1 What is an effective working relationship between project managers themselves?

9–2 Must everyone in the organization understand the “rules of the game” for project management to be effective?

9–3 Defend the statement that the first step in making project management work must be a complete definition of the boundaries across which the project manager must interact.

1. This section and Section 9.3 are adapted from Seminar in Project Management Workbook, copyright 1977 by Hans J. Thamhain. Reproduced by permission of Dr. Hans J. Thamhain.