Modern Developments in Project Management

21.0 INTRODUCTION

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

PMBOK Chapters 1, 2, and 3 (inclusive)

As more industries accept project management as a way of life, the change in project management practices has taken place at an astounding rate. But what is even more important is the fact that these companies are sharing their accomplishments with other companies during benchmarking activities.

Eight recent interest areas are included in this chapter:

- The project management maturity model (PMMM)

- Developing effective procedural documentation

- Project management methodologies

- Continuous improvement

- Capacity planning

- Competency models

- Managing multiple projects

- End-of-phase review meetings

21.1 THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT MATURITY MODEL (PMMM)

All companies desire excellence in project management. Unfortunately, not all companies recognize that the time frame can be shortened by performing strategic planning for project management. The simple use of project management, even for an extended period of time, does not lead to excellence. Instead, it can result in repetitive mistakes and, what's worse, learning from your own mistakes rather than from the mistakes of others.

Companies such as Motorola, Nortel, Ericsson, and Compaq perform strategic planning for project management, and the results are self-explanatory. What Nortel and Ericsson have accomplished from 1992 to 1998, other companies have not achieved in twenty years of using project management.

Strategic planning for project management is unlike other forms of strategic planning in that it is most often performed at the middle-management level, rather than by executive management. Executive management is still involved, mostly in a supporting role, and provides funding together with employee release time for the effort. Executive involvement will be necessary to make sure that whatever is recommended by middle management will not result in unwanted changes to the corporate culture.

Organizations tend to perform strategic planning for new products and services by laying out a well-thought-out plan and then executing the plan with the precision of a surgeon. Unfortunately, strategic planning for project management, if performed at all, is done on a trial-by-fire basis. However, there are models that can be used to assist corporations in performing strategic planning for project management and achieving maturity and excellence in a reasonable period of time.

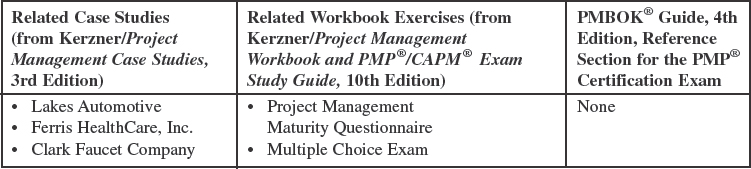

The foundation for achieving excellence in project management can best be described as the project management maturity model (PMMM), which is comprised of five levels, as shown in Figure 21-1. Each of the five levels represents a different degree of maturity in project management.

- Level 1—Common Language: In this level, the organization recognizes the importance of project management and the need for a good understanding of the basic knowledge on project management, along with the accompanying language/terminology.

- Level 2—Common Processes: In this level, the organization recognizes that common processes need to be defined and developed such that successes on one project can be repeated on other projects. Also included in this level is the recognition that project management principles can be applied to and support other methodologies employed by the company.

- Level 3—Singular Methodology: In this level, the organization recognizes the synergistic effect of combining all corporate methodologies into a singular methodology, the center of which is project management. The synergistic effects also make process control easier with a single methodology than with multiple methodologies.

- Level 4—Benchmarking: This level contains the recognition that process improvement is necessary to maintain a competitive advantage. Benchmarking must be performed on a continuous basis. The company must decide whom to benchmark and what to benchmark.

- Level 5—Continuous Improvement: In this level, the organization evaluates the information obtained through benchmarking and must then decide whether or not this information will enhance the singular methodology.

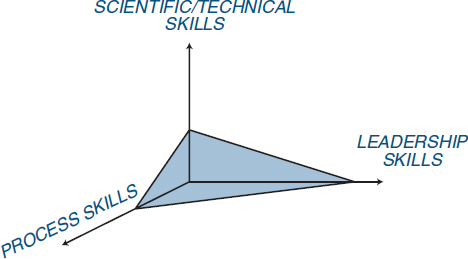

When we talk about levels of maturity (and even life-cycle phases), there exists a common misbelief that all work must be accomplished sequentially (i.e., in series). This is not necessarily true. Certain levels can and do overlap. The magnitude of the overlap is based upon the amount of risk the organization is willing to tolerate. For example, a company can begin the development of project management checklists to support the methodology while it is still providing project management training for the workforce. A company can create a center for excellence in project management before benchmarking is undertaken.

Although overlapping does occur, the order in which the phases are completed cannot change. For example, even though Level 1 and Level 2 can overlap, Level 1 must still be completed before Level 2 can be completed. Overlapping of several of the levels can take place, as shown in Figure 21-2.

FIGURE 21-2. Overlapping levels.

- Overlap of Level 1 and Level 2: This overlap will occur because the organization can begin the development of project management processes either while refinements are being made to the common language or during training.

- Overlap of Level 3 and Level 4: This overlap occurs because, while the organization is developing a singular methodology, plans are being made as to the process for improving the methodology.

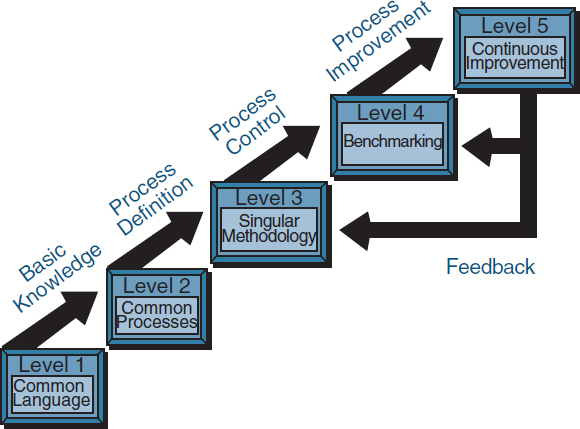

- Overlap of Level 4 and Level 5: As the organization becomes more and more committed to benchmarking and continuous improvement, the speed by which the organization wants changes to be made can cause these two levels to have significant overlap. The feedback from Level 5 back to Level 4 and Level 3, as shown in Figure 21-3, implies that these three levels form a continuous improvement cycle, and it may even be possible for all three of these levels to overlap.

Level 2 and Level 3 generally do not overlap. It may be possible to begin some of the Level 3 work before Level 2 is completed, but this is highly unlikely. Once a company is committed to a singular methodology, work on other methodologies generally terminates. Also, companies can create a Center for Excellence in project management early in the life-cycle process, but will not receive the full benefits until later on.

Risks can be assigned to each level of the PMMM. For simplicity's sake, the risks can be labeled as low, medium, and high. The level of risk is most frequently associated with the impact on the corporate culture. The following definitions can be assigned to these three risks:

FIGURE 21-3. Feedback between the five levels of maturity.

- Low Risk: Virtually no impact upon the corporate culture, or the corporate culture is dynamic and readily accepts change.

- Medium Risk: The organization recognizes that change is necessary but may be unaware of the impact of the change. Multiple-boss reporting would be an example of a medium risk.

- High Risk: High risks occur when the organization recognizes that the changes resulting from the implementation of project management will cause a change in the corporate culture. Examples include the creation of project management methodologies, policies, and procedures, as well as decentralization of authority and decision-making.

Level 3 has the highest risk and degree of difficulty for the organization. This is shown in Figure 21-4. Once an organization is committed to Level 3, the time and effort needed to achieve the higher levels of maturity have a low degree of difficulty. Achieving Level 3, however, may require a major shift in the corporate culture.

These types of maturity models will become more common in the future, with generic models being customized for individual companies. These models will assist management in performing strategic planning for excellence in project management.

FIGURE 21-4. Degrees of difficulty of the five levels of maturity.

21.2 DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE PROCEDURAL DOCUMENTATION_

Good procedural documentation will accelerate the project management maturity process, foster support at all levels of management, and greatly improve project communications. The type of procedural documentation selected is heavily biased on whether we wish to manage formally or informally, but it should show how to conduct project-oriented activities and how to communicate in such a multidimensional environment. The project management policies, procedures, forms, and guidelines can provide some of these tools for delineating the process, as well as a format for collecting, processing, and communicating project-related data in an orderly, standardized format. Project planning and tracking, however, involve more than just the generation of paperwork. They require the participation of the entire project team, including support departments, subcontractors, and top management, and this involvement fosters unity. Procedural documents help to:

- Provide guidelines and uniformity

- Encourage useful, but minimum, documentation

- Communicate information clearly and effectively

- Standardize data formats

- Unify project teams

- Provide a basis for analysis

- Ensure document agreements for future reference

- Refuel commitments

- Minimize paperwork

- Minimize conflict and confusion

- Delineate work packages

- Bring new team members on board

- Build an experience track and method for future projects

Done properly, the process of project planning must involve both the performing and the customer organizations. This leads to visibility of the project at various organizational levels, and stimulates interest in the project and the desire for success.

The Challenges

Even though procedural documents can provide all these benefits, management is often reluctant to implement or fully support a formal project management system. Management concerns often center around four issues: overhead burden, start-up delays, stifled creativity, and reduced self-forcing control. First, the introduction of more organizational formality via policies, procedures, and forms might cost money, and additional funding may be needed to support and maintain the system. Second, the system is seen as causing start-up delays by requiring additional project definition before implementation can start. Third and fourth, the system is often perceived as stifling creativity and shifting project control from the responsible individual to an impersonal process. The comment of one project manager may be typical: “My support personnel feel that we spend too much time planning a project up front; it creates a very rigid environment that stifles innovation. The only purpose seems to be establishing a basis for controls against outdated measures and for punishment rather than help in case of a contingency.” This comment illustrates the potential misuse of formal project management systems to establish unrealistic controls and penalties for deviations from the program plan rather than to help to find solutions.

How to Make It Work

Few companies have introduced project management procedures with ease. Most have experienced problems ranging from skepticism to sabotage of the procedural system. Many use incremental approaches to develop and implement their project management methodology. Doing this, however, is a multifaceted challenge to management. The problem is seldom one of understanding the techniques involved, such as budgeting and scheduling, but rather is a problem of involving the project team in the process, getting their input, support, and commitment, and establishing a supportive environment.

The procedural guidelines and forms of an established project management methodology can be especially useful during the project planning/definition phase. Not only does project management methodology help to delineate and communicate the four major sets of variables for organizing and managing the project—(1) tasks, (2) timing, (3) resources, and (4) responsibilities—it also helps to define measurable milestones, as well as report and review requirements. This provides project personnel the ability to measure project status and performance and supplies the crucial inputs for controlling the project toward the desired results.

Developing an effective project management methodology takes more than just a set of policies and procedures. It requires the integration of these guidelines and standards into the culture and value system of the organization. Management must lead the overall efforts and foster an environment conducive to teamwork. The greater the team spirit, trust, commitment, and quality of information exchange among team members, the more likely the team will be to develop effective decision-making processes, make individual and group commitments, focus on problem-solving, and operate in a self-forcing, self-correcting control mode.

Established Practices

Although project managers may have the right to establish their own policies and procedures, many companies design project control forms that can be used uniformly on all projects. Project control forms serve two vital purposes by establishing a common framework from which:

- The project manager will communicate with executives, functional managers, functional employees, and clients.

- Executives and the project manager can make meaningful decisions concerning the allocation of resources.

Some large companies with mature project management structures maintain a separate functional unit for forms control. This is quite common in aerospace and defense, but is also becoming common practice in other industries and in some smaller companies.

Large companies with a multitude of different projects do not have the luxury of controlling projects with three or four forms. There are different forms for planning, scheduling, controlling, authorizing work, and so on. It is not uncommon for companies to have 20 to 30 different forms, each dependent upon the type of project, length of project, dollar value, type of customer reporting, and other such arguments. Project managers are often allowed to set up their own administration for the project, which can lead to long-term damage if they each design their own forms for project control.

The best method for limiting the number of forms appears to be the task force concept, where both managers and doers have the opportunity to provide input. This may appear to be a waste of time and money, but in the long run provides large benefits.

To be effective, the following ground rules can be used:

- Task forces should include managers as well as doers.

- Task force members must be willing to accept criticism from other peers, superiors, and especially subordinates who must “live” with these forms.

- Upper-level management should maintain a rather passive (or monitoring) involvement.

- A minimum of signature approvals should be required for each form.

- Forms should be designed so that they can be updated periodically.

- Functional managers and project managers must be dedicated and committed to the use of the forms.

Categorizing the Broad Spectrum of Documents

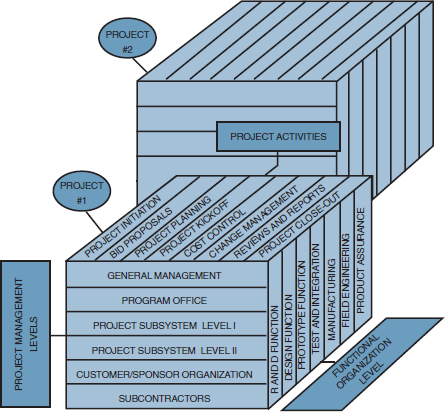

The dynamic nature of project management and its multifunctional involvement create a need for a multitude of procedural documents to guide a project through the various phases and stages of integration. Especially for larger organizations, the challenge is not only to provide management guidelines for each project activity, but also to provide a coherent procedural framework within which project leaders from all disciplines can work and communicate with each other. Specifically, each policy or procedure must be consistent with and accommodating to the various other functions that interface with the project over its life cycle. This complexity of intricate relations is illustrated in Figure 21-5.

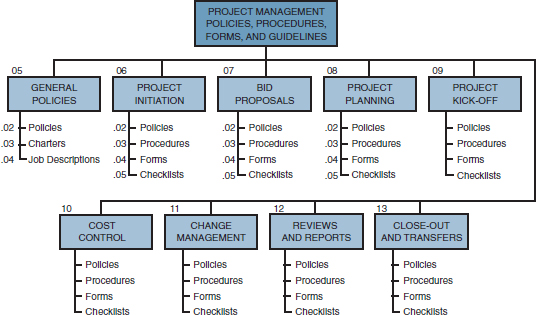

One simple and effective way of categorizing the broad spectrum of procedural documents is by utilizing the work breakdown concept, as shown in Figure 21-6. Accordingly, the principal procedural categories are defined along the principal project life-cycle phases. Each category is then subdivided into (1) general management guidelines, (2) policies, (3) procedures, (4) forms, and (5) checklists. If necessary, the same concept can be carried forward one additional step to develop policies, procedures, forms, and checklists for the various project and functional sublevels of operation. Although this might be needed for very large programs, an effort should be made to minimize “layering” of policies and procedures to avoid new problems and costs. For most projects, a single document covers all levels of project operations.

As We Mature . . .

As companies become more mature in executing the project management methodology, project management policies and procedures are disregarded and replaced with guidelines, forms, and checklists. More flexibility is provided the project manager. Unfortunately, this takes time because executives must have faith in the ability of the project management methodology to work without the rigid controls provided by policies and procedures. Yet all companies seem to go through the evolutionary stages of policies and procedures before they get to guidelines, forms, and checklists.

FIGURE 21-5. Interrelationship of project activities with various functional/organizational levels and project management levels.

FIGURE 21-6. Categorizing procedural documents within a work breakdown structure.

21.3 PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES

The ultimate purpose of any project management system is to increase the likelihood that your organization will have a continuous stream of successfully managed projects. The best way to achieve this goal is with good project management methodologies that are based upon guidelines and forms rather than policies and procedures. Methodologies must have enough flexibility that they can be adapted easily to each and every project.

Methodologies should be designed to support the corporate culture, not vice versa. It is a fatal mistake to purchase a canned methodology package that mandates that you change your corporate culture to support it. If the methodology does not support the culture, it will not be accepted. What converts any methodology into a world-class methodology is its adaptability to the corporate culture. There is no reason why companies cannot develop their own methodology. Companies such as Compaq Services, Ericsson, Nortel Networks, Johnson Controls, and Motorola are regarded as having world-class methodologies for project management and, in each case, the methodology was developed internally. Developing your own methodology internally to guarantee a fit with the corporate culture usually provides a much greater return on investment than purchasing canned packages that require massive changes.

Even the simplest methodology, if accepted by the organization and used correctly, can increase your chances of success. As an example, Matthew P. LoPiccolo, Director of I.S. Operations for Swagelok Company, describes the process Swagelok went through to develop its methodology:

We developed our own version of an I.S. project management methodology in the early 90s. We had searched extensively and all we found were a lot of binders that we couldn't see being used effectively. There were just too many procedures and documents. Our answer was a simple checklist system with phase reviews. We called it Checkpoint.

As strategic planning has become more important in our organization, the need for improved project management has risen as well. Project management has found its place as a key tool in executing tactical plans.

As we worked to improve our Checkpoint methodology, we focused on keeping it simple. Our ultimate goal was to transform our methodology into a one-page matrix that was focused on deliverables within each project phase and categorized by key project management areas of responsibility. The key was to create something that would provide guidance in daily project direction and decision making. In order to gain widespread acceptance, the methodology needed to be easy to learn and quick to reference. The true test of its effectiveness is our ability to make decisions and take actions that are driven by the methodology.

We also stayed away from the temptation to buy the solution in the form of a software package. Success is in the application of a practical methodology not in a piece of software. We use various software products as a tool set for scheduling, communicating, effort tracking, and storing project information such as time, budget, issues and lessons learned.

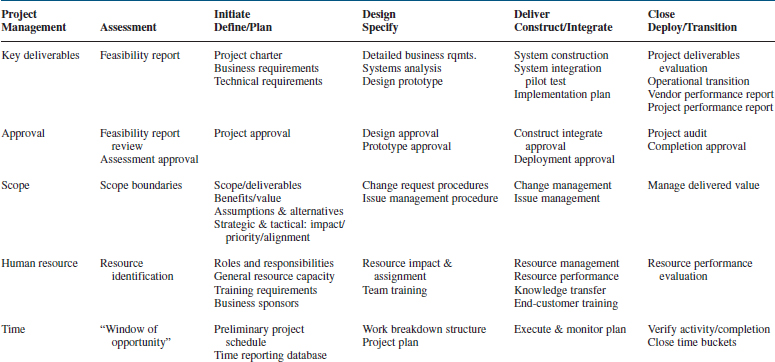

The summary description of the methodology developed by Swagelok is shown in Table 21-1. Swagelok also realized that training and education would be required to support both the methodology and project management in general. Table 21-2 shows the training plan created by Swagelok Company.

21.4 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

All too often complacency dictates the decision-making process. This is particularly true of organizations that have reached some degree of excellence in project management, become complacent, and then realize too late that they have lost their competitive advantage. This occurs when organizations fail to recognize the importance of continuous improvement.

Figure 21-7 illustrates why there is a need for continuous improvement. As companies begin to mature in project management and reach some degree of excellence, they achieve a sustained competitive advantage. The sustained competitive advantage might very well be the single most important strategic objective of the firm. The firm will then begin the exploitation of its sustained competitive advantage.

TABLE 21-1. SWAGELOK COMPANY'S CHECKPOINT METHODOLOGY, VERSION 3

TABLE 21-2. SWAGELOK COMPANY's TRAINING PLAN

FIGURE 21-7. Why there is a need for continuous improvement.

Unfortunately, the competition is not sitting by idly watching you exploit your sustained competitive advantage. As the competition begins to counterattack, you may lose a large portion, if not all, of your sustained competitive advantage. To remain effective and competitive, the organization must recognize the need for continuous improvement, as shown in Figure 21-8. Continuous improvement allows a firm to maintain its competitive advantage even when the competitors counterattack.

FIGURE 21-8. The need for continuous improvement.

21.5 CAPACITY PLANNING

As companies become excellent in project management, the benefits of performing more work in less time and with fewer resources becomes readily apparent. The question, of course, is how much more work can the organization take on? Companies are now struggling to develop capacity planning models to see how much new work can be undertaken within the existing human and nonhuman constraints.

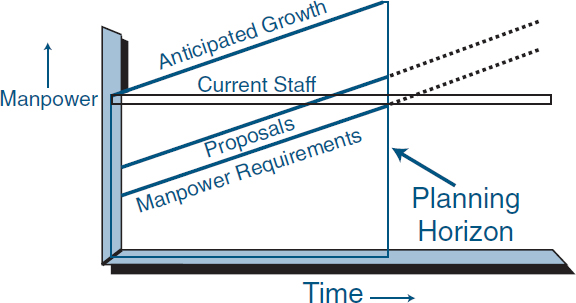

Figure 21-9 illustrates the classical way that companies perform capacity planning. The approach outlined in this figure holds true for both project- and non–project-driven organizations. The “planning horizon” line indicates the point in time for capacity planning. The “proposals” line indicates the manpower needed for approved internal projects or a percentage (perhaps as much as 100 percent) for all work expected through competitive bidding. The combination of this line and the “manpower requirements” line, when compared against the current staffing, provides us with an indication of capacity. This technique can be effective if performed early enough such that training time is allowed for future manpower shortages.

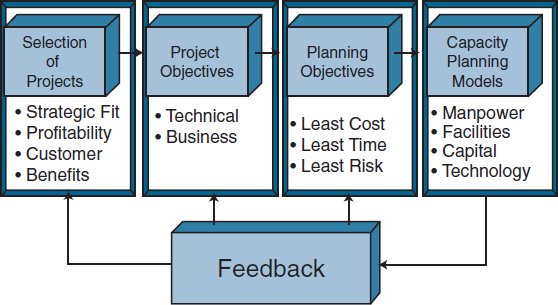

The limitation to this process for capacity planning is that only human resources are considered. A more realistic method would be to use the method shown in Figure 21-10, which can also be applied to both project-driven and non–project-driven organizations. From Figure 21-10, projects are selected based upon such factors as strategic fit, profitability, who the customer is, and corporate benefits. The objectives for the projects selected are then defined in both business and technical terms, because there can be both business and technical capacity constraints.

The next step is a critical difference between average companies and excellent companies. Capacity constraints are identified from the summation of the schedules and plans. In excellent companies, project managers meet with sponsors to determine the objective of the plan, which is different than the objective of the project. Is the objective of the plan to achieve the project's objective with the least cost, least time, or least risk? Typically, only one of these applies, whereas immature organizations believe that all three can be achieved on every project. This, of course, is unrealistic.

FIGURE 21-9. Classical capacity planning.

FIGURE 21-10. Improved capacity planning.

The final box in Figure 21-10 is now the determination of the capacity limitations. Previously, we considered only human resource capacity constraints. Now we realize that the critical path of a project can be constrained not only by time but also by available manpower, facilities, cash flow, and even existing technology. It is possible to have multiple critical paths on a project other than those identified by time. Each of these critical paths provides a different dimension to the capacity planning models, and each of these constraints can lead us to a different capacity limitation. As an example, manpower might limit us to taking on only four additional projects. Based upon available facilities, however, we might only be able to undertake two more projects, and based upon available technology, we might be able to undertake only one new project.

21.6 COMPETENCY MODELS

In the twenty-first century, companies will replace job descriptions with competency models. Job descriptions for project management tend to emphasize the deliverables and expectations from the project manager, whereas competency models emphasize the specific skills needed to achieve the deliverables.

FIGURE 21-11. Competency model.

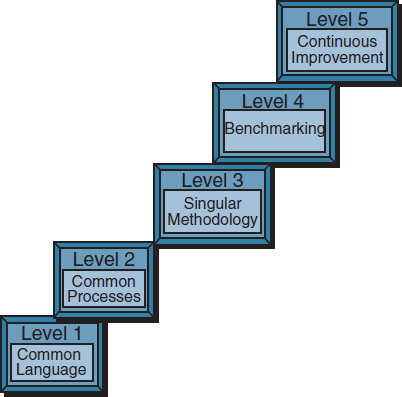

Figure 21-11 shows the competency model for Eli Lilly. Project managers are expected to have competencies in three broad areas1:

- Scientific/technical skills

- Leadership skills

- Process skills

For each of the three broad areas, there are subdivisions or grade levels. A primary advantage of a competency model is that it allows the training department to develop customized project management training programs to satisfy the skill requirements. Without competency models, most training programs are generic rather than customized.

Competency models focus on specialized skills in order to assist the project manager in making more efficient use of his or her time. Figure 21-12, although argumentative, shows that with specialized competency training, project managers can increase their time effectiveness by reducing time robbers and rework.

Competency models make it easier for companies to develop a complete project management curriculum, rather than a singular course. This is shown in Figure 21-13. As companies mature in project management and develop a company-wide core competency model, an internal, custom-designed curriculum will be developed. Companies, especially large ones, will find it necessary to maintain a course architecture specialist on their staff.

FIGURE 21-12. Core competency analysis.

FIGURE 21-13. Competency models and training.

21.7 MANAGING MULTIPLE PROJECTS

As organizations mature in project management, there is a tendency toward having one person manage multiple projects. The initial impetus may come either from the company sponsoring the projects or from project managers themselves. There are several factors supporting the managing of multiple projects. First, the cost of maintaining a full-time project manager on all projects may be prohibitive. The magnitude and risks of each individual project dictate whether a full-time or part-time assignment is necessary. Assigning a project manager full-time on an activity that does not require it is an overmanagement cost. Overmanagement of projects was considered an acceptable practice in the early days of project management because we had little knowledge on how to handle risk management. Today, methods for risk management exist.

Second, line managers are now sharing accountability with project managers for the successful completion of the project. Project managers are now managing at the template levels of the WBS with the line managers accepting accountability for the work packages at the detailed WBS levels. Project managers now spend more of their time integrating work rather than planning and scheduling functional activities. With the line manager accepting more accountability, time may be available for the project manager to manage multiple projects.

Third, senior management has come to the realization that they must provide high-quality training for their project managers if they are to reap the benefits of managing multiple projects. Senior managers must also change the way that they function as sponsors. There are six major areas where the corporation as a whole may have to change in order for the managing of multiple projects to succeed.

- Prioritization: If a project prioritization system is in effect, it must be used correctly such that employee credibility in the system is realized. One risk is that the project manager, having multiple projects to manage, may favor those projects having the highest priorities. It is possible that no prioritization system may be the best solution. Not every project needs to be prioritized, and prioritization can be a time-consuming effort.

- Scope Changes: Managing multiple projects is almost impossible if the sponsors/customers are allowed to make continuous scope changes. When using multiple projects management, it must be understood that the majority of the scope changes may have to be performed through enhancement projects rather than through a continuous scope change effort. A major scope change on one project could limit the project manager's available time to service other projects. Also, continuous scope changes will almost always be accompanied by reprioritization of projects, a further detriment to the management of multiple projects.

- Capacity Planning: Organizations that support the management of multiple projects generally have a tight control on resource scheduling. As a result, the organization must have knowledge of capacity planning, theory of constraints, resource leveling, and resource limited planning.

- Project Methodology: Methodologies for project management range from rigid policies and procedures to more informal guidelines and checklists. When managing multiple projects, the project manager must be granted some degree of freedom. This necessitates guidelines, checklists, and forms. Formal project management practices create excessive paperwork requirements, thus minimizing the opportunities to manage multiple projects. The project size is also critical.

- Project Initiation: Managing multiple projects has been going on for almost 40 years. One thing that we have learned is that it can work well as long as the projects are in relatively different life-cycle phases because the demands on the project manager's time are different for each life-cycle phase.

- Organizational Structures: If the project manager is to manage multiple projects, then it is highly unlikely that the project manager will be a technical expert in all areas of all projects. Assuming that the accountability is shared with the line managers, the organization will most likely adopt a weak matrix structure.

21.8 END-OF-PHASE REVIEW MEETINGS

For more than 20 years, end-of-phase review meetings were simply an opportunity for executives to “rubber stamp” the project to continue. As only good news was presented the meetings were used to give the executives some degree of comfort concerning project status.

Today, end-of-phase review meetings take on a different dimension. First and foremost, executives are no longer afraid to cancel projects, especially if the objectives have changed, if the objectives are unreachable, or if the resources can be used on other activities that have a greater likelihood of success. Executives now spend more time assessing the risks in the future rather than focusing on accomplishments in the past.

Since project managers are now becoming more business-oriented rather than technically oriented, the project managers are expected to present information on business risks, reassessment of the benefit-to-cost ratio, and any business decisions that could affect the ultimate objectives. Simply stated, the end-of-phase review meetings now focus more on business decisions, rather than on technical decisions.

1. A detailed description of the Eli Lilly competency model and the Ericsson competency model can be found in Harold Kerzner, Applied Project Management (New York: Wiley, 1999), pp. 266–283.